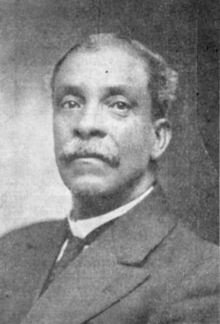

Frank Trigg | |

|---|---|

Frank Trigg (1923) | |

| 8th President of Bennett College | |

| In office 1915 – June 1926 | |

| Preceded by | James E. Wallace |

| Succeeded by | David Dallas Jones |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Frank John Trigg Jr. c. 1850 Abingdon, Virginia, United States |

| Died | April 21, 1933 Lynchburg, Virginia, United States |

| Resting place | Old City Cemetery |

| Spouse | Ellen Preston Taylor (m. 1879–1933; his death) |

| Children | 2 |

| Education | Hampton Institute |

Frank John Trigg Jr. (c. 1850–1933) was an American educator, academic administrator, and college president. He served as the 8th president of Bennett College, a historically black women's college in Greensboro, North Carolina. Trigg was the first first black male teacher and the first Black high school principal in the city of Lynchburg, Virginia.[1]

Early life and education[edit]

Frank Trigg was born in c. 1850, in Abingdon, Virginia, United States to enslaved parents Sarah Ann and Frank Trigg.[1] Some records described him as "mulatto". He was born enslaved, and owned by John Buchanan Floyd, the 31st Governor of Virginia.[2][3] Trigg lost his right arm in a threshing accident at age 13.[3] After Floyd's death in 1863, Trigg who now had one arm was inherited by Floyd's son-in-law named Hughes, who suggested Trigg start his education since he could no longer be a physical worker.[3]

In 1870, he enrolled at Hampton Institute (now Hampton University), where he met Booker T. Washington.[3]

Career[edit]

After graduation from Hampton Institute, Trigg taught in Abingdon, Virginia from 1873 to 1880.[3] This was followed by a move to Lynchburg, Virginia to teach at Jackson Street High School (later known as Lynchburg Colored High School) for the next 22 years, and where he also served as principal.[3][4] He was the first superintendent of black schools in Lynchburg.[3]

In 1902, the family moved to Maryland, and Trigg was principal at Princess Anne Academy (now the University of Maryland Eastern Shore) from 1902 to 1910.[3] Followed by serving as principal of Virginian Collegiate and Industrial Institute, a branch of Morgan College (now Morgan State University) in Baltimore, Maryland.[3] Trigg served as president of Bennett College in Greensboro, North Carolina from 1915 to 1926.[5]

The Virginia Teachers' Association for Blacks was co-founded by Trigg.[3] Frank Trigg is discussed in the book, The Afro-American Press and Its Editors (1891) by Irvine Garland Penn; and The Colored American published a “Men of the Hour” profile of Trigg in 1903 praising his innovative education work.[1]

Death and legacy[edit]

Trigg died on April 21, 1933 in Lynchburg. He was buried at the Old City Cemetery in Lynchburg.[1][3][6]

His son Harold Leonard Trigg (1893–1978) also worked as an educator and college president.[7]

In 2011, a historical marker in his memory was erected by the Virginia Department of Historic Resources (DHR) in Lynchburg.[8] Trigg had lived in a residence at 1422 Pierce Street in Lynchburg, and later the home of Dr. Robert Walter Johnson; the house named the Dr. Robert Walter Johnson House and Tennis Court was subject to preservation efforts.[9]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d "The 125th Anniversary of UMES, Frank Trigg". University of Maryland Eastern Shore (UMES). Retrieved 2024-06-15.

- ^ Michigan Christian Advocate. 1923. p. 23 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Holowchak, M. Andrew; Holowchak, David M. (March 1, 2021). "A "Biography" of Lynchburg: City with a Soul". Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 219–221 – via Google Books.

- ^ "The Virginia School Journal". Virginia State Board of Education. December 2, 1892 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Bennett College, a Haven for Education..." The African American Registry. 2007-12-01. Retrieved 2024-06-15 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "Trigg-T05441". Old City Cemetery. Retrieved 2024-06-15.

- ^ Powell, William S. (2000-11-09). Dictionary of North Carolina Biography: Vol. 6, T-Z. University of North Carolina Press. p. 52. ISBN 978-0-8078-6699-3 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Professor Frank Trigg Historical Marker". Historical Marker Database (HMDB). Retrieved 2024-06-16.

- ^ Sarafin, Justin (2014-12-23). Preservation Virginia’s Most Endangered Historic Sites List:: Updates on Past Listings 2000 through 2014. Preservation Virginia – via Google Books.