| Siege of Coron | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Morean War | |||||||

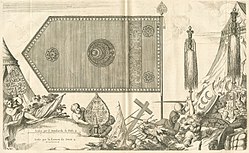

The siege of Coron, depicted by Vincenzo Coronelli | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Ottoman Empire | Republic of Venice | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Halil Pasha | Francesco Morosini | ||||||

The Siege of Coron was the capture of the Ottoman fortress of Coron (Koroni) in the southwestern Morea (Peloponnese) by the Republic of Venice in 1685. It signalled the start of the Venetian conquest of the Morea during the Great Turkish War.

Background[edit]

Before its loss to the Ottomans in 1500 during the Second Ottoman–Venetian War, Coron had been under Venetian possession for three centuries and was known alongside neighbouring Modon (Methoni) as the "chief eyes of the Republic", for their strategic position controlling the sea-lanes from the eastern to the central Mediterranean.[1][2] The bloody loss of Modon in particular, whose garrison was massacred, was long remembered and rankled among the Venetians.[3] With the assistance of the local population, the town was captured by the admiral Andrea Doria in 1532 for the Spanish Habsburgs. The Habsburgs offered to return this isolated outpost to Venice, but the Republic refused, and the Ottomans recaptured the town after a siege that lasted into spring 1534 and forced its population to abandon it.[4][5] Apart from the governor, his officials, and the 300-strong garrison, who were Muslims, the fortress was inhabited mostly by Christians, with some Jewish families present as well.[4]

In March 1684, with the Ottoman Empire smarting from its defeat at the Battle of Vienna and its military forces embroiled in a costly war with the Habsburg empire and Poland, Venice joined the anti-Ottoman Holy League with the aim of conducting a parallel campaign in Greece,[6][7] and thus exact revenge for the recent loss of Crete.[8] For the first and only time in the Ottoman–Venetian wars, it was the Republic that declared war on the Ottomans.[6][9] The opening actions of the Morean War in Greece saw the capture of Santa Maura (Lefkada) and the mainland fortress of Preveza in 1684,[10][11] but the main aim of the Venetian commander-in-chief, Francesco Morosini, was to capture the Morea as recompense for the loss of Crete.[12] In this he hoped for assistance from the native Greek population, which was showing signs of revolutionary stirrings that worried the Ottoman authorities. This was especially the case for the Maniots, the restive and semi-autonomous inhabitants of the mountainous Mani Peninsula, and who resented the loss of privileges and autonomy, including the establishment of Ottoman garrisons in local fortresses, that they had suffered due to their collaboration with the Venetians during the Cretan War. The Maniots entered into negotiations with the Venetian commander-in-chief, Francesco Morosini, but the Ottomans pre-empted them: in spring 1685 the serasker of the Morea, Ismail Pasha, invaded Mani and forced the local population to submit, giving up their children as hostages.[13][14]

Siege of Coron[edit]

At the same time as the Ottomans subdued the Maniots, the Venetian forces were being marshalled in Corfu, Dragamesto and Preveza.[15] The army comprised some 8,200 men: 3,100 Venetian mercenaries and 1,000 Schiavoni, 2,400 soldiers hired from the Duchy of Brunswick-Lüneburg, 1,000 men provided by the Knights Hospitaller of Malta, 400 Papal troops, and 300 men from the Grand Duchy of Tuscany.[16] The fleet was equally multinational, comprising Venetian, Tuscan, Hospitaller and Papal vessels.[15]

On 24 June, the Venetian fleet entered the Messenian Gulf.[15] Morosini sent only four vessels with ammunition and supplies to support the Maniots in March, leading to the latter adopting a cautious stance when the Venetian commander decided to land; on the way to the Morea, Maniot envoys had met Morosini and asked him not to land at Mani, warning that the Maniots would not rise up until the Venetians had taken hold of a major fortress as a base of operations and refuge for their local allies.[15][17] As a result, Morosini chose Coron as his first target, lying across the Messenian Gulf from Mani.[18]

The siege of the fortress began upon the disembarkation of the army on 25 June. The Ottoman garrison withdrew into the citadel, located at the tip of the promontory on which Coron lies, while the town itself was occupied without resistance. Siege lines were dug to cut off the citadel from the hinterland, artillery emplacements built in the town and its nearby heights to complement the bombardment of the fleet, and the olive groves cut down to remove cover for any Ottoman relief attempt.[18] Very quickly, the Venetian positions around Coron were threatened by the troops led by the governor of Nauplia, Halil Pasha.[15]

The Ottoman relief force arrived at Coron on 7 July, making camp close to the Venetian lines; the two armies were separated by a small hill, which the Venetians had fortified. The hill became the focal point of the siege, as both sides tried to capture or retake it, and it changed possession several times.[18] At the same time, the Venetians continued their efforts to breach the citadel, feinting towards the southern wall but hoping to breach the citadel at its strongest point, the circular bastion on its western end. To that end, Maltese troops employed a hundred barrels of gunpowder, but the only effect was to create a breach that was filled by the falling stones from the wall.[19] The explosion did however trigger another assault by the Ottoman relief army, which succeeded in pushing the Venetians back from their outer defences. The situation was saved by a pre-dawn attack on 7 August, which overwhelmed the relief army and secured the Venetian rear.[20]

Free to concentrate on the siege, the Venetians and their allies dug two parallel tunnels under the western bastion, and filled mines with 250 gunpowder barrels recovered from the Ottoman relief army. The mine was exploded at dawn on 11 August, followed by an attack into the resulting breach. After a hard three-hour fight, the Venetians were pushed back, but returned to the attack by noon, while a small detachment was landed over water in the eastern rear of the fortress. Shortly after the signal for the general assault was given, the Ottoman garrison raised the white flag in token of surrender, and the attack stopped.[20] While negotiations were taking place for the surrender of the garrison, a cannon accidentally exploded; taking this as a sign of treachery, the Venetians and their allies stormed the citadel and massacred the garrison and its inhabitants, some 1,500 people in all.[21][17]

Aftermath[edit]

In the final stage of the siege, 230 Maniots under the Zakynthian noble Pavlos Makris had taken part, and soon the area rose up in revolt again, encouraged by Morosini's presence at Coron.[15] The Venetians and Maniots captured the fortress of Zarnata, allowing its garrison passage to Kalamata, where the Kapudan Pasha had landed an army of 6,000 infantry and 2,000 sipahi cavalry. At the ensuing Battle of Kalamata on 14 September the Venetians under Hannibal von Degenfeld, defeated the Ottoman army. By the end of September the remaining Ottoman garrisons in Mani had capitulated and evacuated the region. The castle of Passavas was razed, but the Venetians in turn installed their own garrisons in Kelefa and Zarnata, as well as the offshore island of Marathonisi, to keep an eye on the unruly Maniots, before returning to the Ionian Islands to winter.[15][22] Morosini's campaign in the next year completed the conquest of Messenia with the siege and capture of New Navarino fortress, followed by the capture of Modon.[23][24]

References[edit]

- ^ Barzman 2017, p. 118.

- ^ Andrews 1978, p. 14.

- ^ Barzman 2017, pp. 118–120.

- ^ a b Heywood 1986, pp. 270–271.

- ^ Andrews 1978, p. 15.

- ^ a b Chasiotis 1975, p. 19.

- ^ Setton 1991, p. 271.

- ^ Topping 1976, p. 160.

- ^ Finlay 1877, p. 172.

- ^ Setton 1991, p. 295.

- ^ Chasiotis 1975, pp. 20–21.

- ^ Finlay 1877, p. 176.

- ^ Chasiotis 1975, pp. 20, 22–23.

- ^ Finlay 1877, pp. 176–177.

- ^ a b c d e f g Chasiotis 1975, p. 23.

- ^ Setton 1991, pp. 295–296.

- ^ a b Finlay 1877, p. 177.

- ^ a b c Andrews 1978, p. 11.

- ^ Andrews 1978, pp. 11–12.

- ^ a b Andrews 1978, p. 12.

- ^ Andrews 1978, pp. 12–13.

- ^ Finlay 1877, pp. 177–179.

- ^ Setton 1991, pp. 296–297.

- ^ Chasiotis 1975, pp. 23–24.

Sources[edit]

- Andrews, Kevin (1978) [1953]. Castles of the Morea. Amsterdam: Adolf M. Hakkert. ISBN 90-256-0794-2.

- Barzman, Karen-edis (2017). The Limits of Identity: Early Modern Venice, Dalmatia, and the Representation of Difference. Brill. ISBN 978-90-0433151-8.

- Chasiotis, Ioannis (1975). "Η κάμψη της Οθωμανικής δυνάμεως" [The decline of Ottoman power]. In Christopoulos, Georgios A. & Bastias, Ioannis K. (eds.). Ιστορία του Ελληνικού Έθνους, Τόμος ΙΑ΄: Ο Ελληνισμός υπό ξένη κυριαρχία (περίοδος 1669 - 1821), Τουρκοκρατία - Λατινοκρατία [History of the Greek Nation, Volume XI: Hellenism under Foreign Rule (Period 1669 - 1821), Turkocracy – Latinocracy] (in Greek). Athens: Ekdotiki Athinon. ISBN 978-960-213-100-8.

- Finlay, George (1877). A History of Greece from its Conquest by the Romans to the Present Time, B.C. 146 to A.D. 1864, Vol. V: Greece under Othoman and Venetian Domination A.D. 1453–1821. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Heywood, C. J. (1986). "Ḳoron". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Lewis, B. & Pellat, Ch. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume V: Khe–Mahi. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 270–271. ISBN 978-90-04-07819-2.

- Setton, Kenneth Meyer (1991). Venice, Austria, and the Turks in the Seventeenth Century. Philadelphia: The American Philosophical Society. ISBN 0-87169-192-2.

- Topping, Peter (1976). "Venice's Last Imperial Venture". Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. 120 (3): 159–165. JSTOR 986555.

Primary accounts[edit]

- Coronelli, Vincenzo (1687). An Historical and Geographical Account of the Morea, Negropont, and the Maritime Places, as Far as Thessalonica: Illustrated with 42 Maps of the Countries, Plains, and Draughts of the Cities, Towns and Fortifications. Translated by R. W. Gent. London. pp. 61–84.

- Locatelli, Alessandro (1691). Racconto historico della Veneta guerra in Levante diretta dal valore del Serenissimo Principe Francesco Morosini (in Italian). Cologne. pp. 124–152.

- The History of the Venetian Conquests, from the Year 1684 to this Present Year 1688. Translated Out of French by J. M. London: John Newton. 1688. pp. 35–51.