| |

| Author | Prof. Dr. Robert Sommer (1864-1937) |

|---|---|

| Country | Germany |

| Language | German |

| Publisher | Urban & Schwarzenberg |

Publication date | 1899 |

Lehrbuch der Psychopathologischen Untersuchungs-Methoden (English: Textbook on research methods of psychopathology) is a German book written by Robert Sommer (1864-1937), first published in 1899 by Urban & Schwarzenberg. In its 388 pages, Sommer presents a framework of ideas delving into the core of psychopathological symptoms, employing new analytical techniques and psychophysiological experiments.[1][2]

Context[edit]

Sommer studied medicine and philosophy in Freiburg im Breisgau and Leipzig. In 1887, he attained his Ph.D. in philosophy for his dissertation on the relationship between John Locke (1632-1704) and René Descartes (1596-1650).[1] He started working as an assistant, first in the laboratory of Wilhelm Wundt (1832-1920) in Leipzig, and then in a psychiatric hospital in Rybnik in 1889. During this time, Sommer noticed a deficiency in the available tools for psychopathological research.[1][2] He recognized that some of these tools were already employed in the fields of physics, physiology, and psychophysics. He was determined to adapt and apply these methods to the field of psychopathology and develop new ones, tailored to the special purposes and objects he aimed to investigate.[2]

Mental illness was first to be considered as a disease by the Ancient Greeks. During the ancient times, the primary proponents of this view were the Hippocrates and Galen. In the pre-Hippocratic era, a demonological model existed, attributing abnormal behavior as supernatural.[3][4] The belief that the body could be possessed by evil or domestic spirits, curses, and sin gained even greater prominence during the "Dark Ages" (as seen in the Malleus Maleficarum (1486)).[3][5] After the 1750s, new philosophical concepts of sensation and perception, advocated by Locke, contributed to a theoretical transformation. His idea that madness resulted from faulty associations in the mental processes, changed the understanding of mental illness.[4] When William Cullen (1710-1790) linked lunacy to nerve irritation and cerebral activity, the concept of insanity being a psychological condition gained wider acceptance.[4] It was not until the 19th century that psychology as a science emerged. At the beginning of the 19th century, the field of physiology emerged, revealing the inner workings of the human body's mechanism. From understanding the cardiovascular system to unveiling the mechanisms of respiration, improving the understanding of human anatomy. From this, neurophysiology was formed, delving into the inner recess of the nervous system, and answering questions about how the neurons and synapses in the human body work.[6] Both physiology and neurophysiology laid the foundations for the development of scientific psychology during the 19th century. Another milestone during this time was the establishment of the first experimental psychology laboratory in Leipzig by Wundt in 1879[7] which laid the cornerstone for empirical experimentation.[6][8]

Contents[edit]

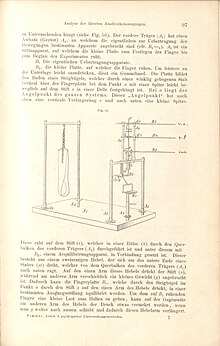

The book is structured into four sections, each about the different methods explaining the human body and its processes. In part 1, "Representation of the Visual Appearance" (German: "Darstellung der optischen Erscheinung"), Sommer explains the visual appearance shown by patients with mental illness and how these aspects are perceived and documented. Part 2, "Analysis of the Movement Process Causing the Phenomena with Motor-Graphic Methods" (German: "Analyse der die Erscheinungen bedingenden Bewegungsvorgänge mit motorisch-graphischen Methoden"), is an extension of part 1. Sommer explains that the external bodily movements observed in mentally ill patients lead to internal change. He notes that the muscle states are dependent on nerve excitations, further describing different methods for researching these nerve or brain processes.[2]

In part 3, "Representation of the Acoustic Expression" (German: "Darstellung der Akustischen Äußerungen"), Sommer discusses the difficulty of representing vocal expressions of the mentally ill. He examines different methods for representing language and expressions of patients, while he also notes the potential errors that come along with representing vocal expressions. In part 4, "Study of the mental states and processes" (German: "Untersuchung der psychischen Zustände und Vorgänge"), the focus deepens into the inner workings of the patient, revealing new methods to analyze patients mental states.[2]

Reception[edit]

Sommer's work has been described as an "importance of empirical, inductive methodology for scientific development, which opposes dogmatic rigidity in systems distant from reality".[9] However, after his publication of the "Textbook on Research Methods of Psychopathology" the book experienced rejection due to its abstraction and the dogmatic bias of the population during that time.[10] Kurt v. Leupoldt mentions that the book contains many suggestions that would resonate more readily with contemporary readers compared to the reception it received during its original time. Sommer's eye for broader elevated his work beyond the narrower confines of his subject positioning his work way ahead of time. Sommer's work has never been "dryly doctrinal" and out of touch with life, but always stimulating and firmly connected to life.[10]

Sommer's engagement with psychophysiological investigation methods led him to the conception of individual reaction types, which he regarded as inherited. His books on "Family Research" (German: "Familienforschung") and "Heredity Theory" (German: "Vererbungslehre") were designed to capture innate responsiveness through a methodical theory of heredity, and an in-depth examination of family characteristics. These individual publications by Sommer, increased the interest in experimental-based psychopathological research, steadily building momentum and interest in the field.[11] In 1925, Sommer founded the "German Association for Mental Hygiene" (German: "Deutschen Verband für psychische Hygiene"), and served as its chairman until 1933. Early on, he advocated a reform of psychiatric care in the form of city asylums along the lines of Wilhelm Griesinger (1817-1868).[9] Sommer's individual psychological concept of the interplay between endogenous disposition and exogenous stimuli, led him to a form of social psychology that aimed to shape societal conditions to enable each person to be able to develop to the fullest possible extent according to his or her disposition, while eliminating harmful environmental influences. At the 3rd General Medical Congress for Psychotherapy (German: Allgemeinen ärztlichen Kongress) in 1928, Sommer announced the founding of the 'General Medical Society for Psychotherapy', of which he became chairman.[9]

Psychology began to unfold and explore, reaching out to understand more about the complexities of human life. The focus switched from looking at our thoughts to expanding and including the whole range of the distinct behaviors of individuals.[12] As ideas from different fields came together, psychology grew into knowledge that went beyond just understanding consciousness. It began to concentrate on the uniqueness of individual behavior connecting deeply with the essence of humanity. All this knowledge came together and modern psychology emerged, showing how our understanding of people keeps growing and improving over time.[12] Since 1996, a medal, the Robert Sommer Award Medal exists as a memory medal in regards to the founder, Robert Sommer, of the Centre of Psychiatry.[13]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c Zeno. "Lexikoneintrag zu »Robert Sommer«. Pagel: Biographisches Lexikon hervorragender Ärzte ..." www.zeno.org (in German). Retrieved 2023-08-24.

- ^ a b c d e Sommer, Robert (1899). Lehrbuch der Psychopathologischen Untersuchungs-Methoden. Berlin: Urban & Schwarzenberg.

- ^ a b Mueller, Ronald H. "The origin and development of the medical model of psychopathology". Electronic Theses and Dissertations.

- ^ a b c Porter, Roy (2002). Madness: a brief history. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-280266-8.

- ^ Brewer, Lauren. "General Psychology: Required Reading". Noba. Retrieved 2023-10-04.

- ^ a b "History of Psychology in the Nineteenth Century". Psychology. Retrieved 2023-10-05.

- ^ "Experimentelle Psychologie". www.spektrum.de (in German). Retrieved 2023-08-25.

- ^ Mandler, George (2007). A history of modern experimental psychology: from James and Wundt to cognitive science. A Bradford book. Cambridge (Mass.): MIT. ISBN 978-0-262-13475-0.

- ^ a b c Meyer Zum Wischen, Michael (1986). "Robert Sommer (1864- 1937). Forschungsschwerpunkt Deutsche Psychiatriegeschichte". Geschichte der Psychologie - Nachrichtenblatt (in German). Leibniz Institut Für Psychologie (ZPID), Leibniz Institut Für Psychologie (ZPID). doi:10.23668/PSYCHARCHIVES.260.

- ^ a b von Leupoldt, Curt (Jan 1, 1935). "Robert Sommer zum 70. Geburtstag". Georg Thieme Verlag KG. 61: 30–31. doi:10.1055/s-0028-1129418. S2CID 72764073.

- ^ Hildebrandt, Helmut (1993). "Der psychologische Versuch in der Psychiatrie: Was wurde aus Kraepelins (1895) Programm?". Psychologie und Geschichte (in German). Leibniz Institut Für Psychologie (ZPID), Leibniz Institut Für Psychologie (ZPID). doi:10.23668/PSYCHARCHIVES.456.

- ^ a b "History of Psychology in the Nineteenth Century". Psychology. Retrieved 2023-08-26.

- ^ "Robert Sommer Award Website". Robert Sommer Research Society. Archived from the original on 2017-06-27.