The Red Hat of Pat Ferrick (talk | contribs) restore new map: pink areas are dubious and confusing |

EuroHistoryTeacher (talk | contribs) claims/explorations should be shown (not including the torsedilla claims), please stop removing it User Pat Ferrick |

||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

|name = Portuguese Empire |

|name = Portuguese Empire |

||

|image_flag = Flag_Portugal_(1578).svg |

|image_flag = Flag_Portugal_(1578).svg |

||

|image_map = |

|image_map = Portugal Império total.png|thumb|460px |

||

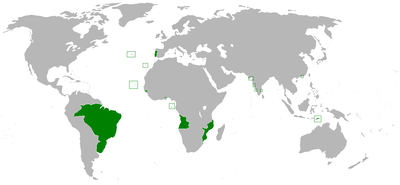

|map_caption = Red - the colonies, forts and trading ports that at one time were under Portuguese rule |

|map_caption = Red - the colonies, forts and trading ports that at one time were under Portuguese rule; Pink - Areas of influence and claims of sovereignity; Blue - the main areas of Portuguese seaborne exploration and trade. The [[Theory of Portuguese discovery of Australia|disputed discovery of Australia]] is not shown. |

||

}} |

}} |

||

The '''Portuguese Empire''' was the earliest and longest lived of the modern [[Europe]]an [[Colonialism|colonial]] empires, spanning almost six centuries, from the capture of [[Ceuta]] in 1415 to the handover of [[Macau]] in 1999. |

The '''Portuguese Empire''' was the earliest and longest lived of the modern [[Europe]]an [[Colonialism|colonial]] empires, spanning almost six centuries, from the capture of [[Ceuta]] in 1415 to the handover of [[Macau]] in 1999. |

||

Revision as of 02:55, 17 January 2009

Portuguese Empire | |

|---|---|

Red - the colonies, forts and trading ports that at one time were under Portuguese rule; Pink - Areas of influence and claims of sovereignity; Blue - the main areas of Portuguese seaborne exploration and trade. The disputed discovery of Australia is not shown. |

The Portuguese Empire was the earliest and longest lived of the modern European colonial empires, spanning almost six centuries, from the capture of Ceuta in 1415 to the handover of Macau in 1999.

Portuguese explorers began exploring the coast of Africa in 1419, making use of the latest developments in navigation, cartography and maritime technology such as the caravel, in order that they might find a sea route to the source of the lucrative spice trade. In 1488, Bartolomeu Dias rounded the Cape of Good Hope, and in 1498, Vasco da Gama reached India. In 1500, by an accidental landfall on the South American coast for some, by the crown's secret design for others, Pedro Álvares Cabral would find and lead to the establishment of the colony of Brazil. Over the following decades, Portuguese sailors continued to explore the coasts and islands of East Asia, establishing forts and trading posts as they went. By 1571, a string of outposts connected Lisbon to Nagasaki: the empire had become truly global, and in the process brought great wealth to Portugal.

Between 1580 and 1640 Portugal became the junior partner to Spain in the union of the two countries' crowns. Though the empires continued to be administered separately, Portuguese colonies became the subject of attacks by three rival European powers hostile to Spain and envious of Iberian successes overseas: The Netherlands (which was engaged in a war of independence against Spain), England and France. With a smaller population, Portugal was unable to effectively defend its overstretched network of trading posts and factories, and so the empire began its long and gradual decline. The loss of Brazil in 1822, by then Portugal's largest and most profitable colony, at a time when independence movements were sweeping the Americas, was a blow from which Portugal and its empire would never recover.

The Scramble for Africa which began in the late 19th century left Portugal with a handful of colonies on the continent. Most of these African territories were under Portuguese administration and influence for centuries. Cities like Luanda and Benguela, and dozens of other settlements, ports and forts, had been founded and ruled by Portugal since the 16th century. After World War II, Portugal's right-wing dictator, António Salazar, attempted to keep the Portuguese Empire intact at a time when other European countries were beginning to withdraw from their colonies. In 1961 the handful of Portuguese troops garrisoned in Goa were unable to prevent Indian troops marching into the colony. Salazar began a long and bloody war to quell anti-colonialist forces in the African colonies. The unpopular war lasted until the overthrow of the regime in 1974, known as the Carnation Revolution. The new government immediately changed policy and recognised the independence of all its colonies, except for Macau, which by agreeement with the Chinese government was returned to China in 1999, marking the end of the Portuguese overseas empire.

The Community of Portuguese Language Countries (CPLP) is the cultural successor of the Empire.

Origins (1139-1415)

The origins of the Portuguese Empire, and of Portugal itself, lay in the reconquista—the Christian reconquest of the Iberian peninsula from the Moors. After establishing itself as a separate kingdom in 1139, Portugal completed its reconquista by 1249, but its independence continued to be threatened by neighbouring Castile until the signing of the Treaty of Ayllón in 1411. Free from threats to its existence, Portuguese attention turned overseas and towards a military expedition to the Muslim lands of North Africa.[1] There were several probable motives for an attack on the Marinid Sultanate in present-day Morocco. It offered the opportunity to continue the Christian crusade aspect of the reconquista against Islam. To the military class, it promised glory on the battlefield and the spoils of war.[2] It was also a chance to expand Portuguese trade and to address Portugal's economic decline.[3]

In 1415 an attack was made on Ceuta, a strategically located Muslim city at the mouth of the Mediterranean Sea, and one of the terminal ports of the trans-Saharan gold and slave trades. The Battle of Ceuta was a military success, and marked the beginning of the Portuguese colonial enterprise,[4] but it proved costly to defend against the Muslim forces that soon besieged it. The Portuguese were unable to use it as a base for further expansion into the hinterland,[5] and the trans-Saharan trade routes shifted to use alternative Muslim ports.[6]

Age of discovery (1415-1494)

Although Ceuta proved to be a disappointment for the Portuguese, the decision was taken to hold it while exploring along the Atlantic African coast.[7] A key supporter of this policy was Prince Henry the Navigator, who had been involved in the capture of Ceuta, and who took the lead role in encouraging Portuguese maritime exploration until his death in 1460.[8] At the time, Europeans did not know what lay beyond Cape Bojador on the African coast, and Henry was curious to find out. He wished to know how far the Muslim territories in Africa extended, and whether it was possible to reach Asia by sea, both to reach the source of the lucrative spice trade and perhaps to join forces with the long-lost Christian kingdom of Prester John that was rumoured to exist somewhere in the "Indies".[9][10]

In 1419 two of Henry's captains, João Gonçalves Zarco and Tristão Vaz Teixeira were driven by a storm to Madeira, an uninhabited island off the coast of Africa which had probably been known to Europeans since the 14th century. In 1420 Zarco and Teixeira returned with Bartolomeu Perestrelo and began Portuguese settlement of the the islands. A Portuguese attempt to capture Grand Canary, one of the the nearby Canary Islands, which had been partially settled by Spaniards in 1402 was unsuccessful and met with protestations from Castile.[11] Although the exact details are uncertain, cartographic evidence suggests the Azores were probably discovered in 1427 by Portuguese ships sailing under Henry's direction, and settled in 1432, suggesting that the Portuguese were able to navigate at least Template:Mi to km from the Portuguese coast.[12]

At around the same time as the unsuccessful attack on the Canary Islands, the Portuguese began to explore the North African coast. Sailors' fears of what lay beyond Cape Bojador, and whether it was possible to return once it was passed, were finally conquered in 1434 by one of Prince Henry's captains, Gil Eanes. Once this psychological barrier had been crossed, it became easier to probe further along the coast.[13] Henry suffered a serious setback in 1437 after the failure of an expedition to capture Tangier. Henry had encouraged his brother, King Edward, to mount the overland attack from Ceuta but the Portuguese army was defeated and only escaped destruction by surrendering Prince Ferdinand, the king's youngest brother.[14]

After the defeat at Tangier, Henry retired to Sagres on the southern tip of Portugal where he continued to direct Portuguese exploration. A major advance which aided the project was the introduction of the caravel in the mid-15th century, a ship that could be sailed closer to the wind than any other in operation in Europe at the time.[15] In 1441, the first consignment of slaves was brought to Lisbon and slave trading soon became one of the most profitable branches of Portuguese commerce. Senegal and Cape Verde were reached in 1445. In 1446, António Fernandes pushed on almost as far as present-day Sierra Leone.

Meanwhile, colonization continued in the Azores (from 1439) and Madeira, where sugar and wine were now produced by settlers from Portugal, France, Flanders and Genoa. Above all, gold brought home from Guinea stimulated the commercial energy of the Portuguese. The Atlantic voyages had proved to be highly profitable as economic enterprises, while the religious and military motives for exploration became more symbolic.

Under Afonso V, the African (1443–1481), the Gulf of Guinea was explored as far as Cape St Catherine, and three expeditions (1458, 1461, 1471) were sent to Morocco. In 1458, Alcácer Ceguer (El Qsar es Seghir, in Arabic) was taken. In 1471, Arzila (Asila) and at last Tangier were captured.

In 1474 João Vaz Corte-Real received a capitancy in Azores for the discovery of Terra Nova dos Bacalhaus (New Land of Codfish) in 1472. Some claim this land was modern-day Newfoundland. Whether or not this is actually the case is difficult to ascertain, as the Portuguese were secretive about their discoveries and little documented evidence of them remains[citation needed]. However, the Canadian Maritimes were visited by Portuguese sailors within the next few decades, and the abundant cod they found off its coast attracted many Portuguese fisherman. Dried cod became an important economic commodity and a staple of the Portuguese diet.

Portugal secured rights to explore the African coast south of the Castillian-controlled Canary Islands through the marriage of King Afonso V of Portugal to Joan of Castile. To the displeasure of Queen Isabella, Afonso could now make a claim to the throne of Castile-León, which she herself had claimed. By the Treaty of Alcáçovas, signed in 1479, Afonso relinquished his claim in exchange for exclusive sea navigation rights in the southeast Atlantic.

In 1482, the Portuguese established a fort in the Gulf of Guinea, São Jorge da Mina, which gave them access to the gold trade of western Sudan. The same year Diogo Cão reached the Congo and in 1486, Cape Cross. In 1488, Bartolomeu Dias rounded the Cape of Good Hope, inaugurating the sea route to the Indian Ocean.[16] As the Portuguese explored the coastlines of the Congo and beyond, they left a series of padrãoes, stone crosses enscribed with the Portuguese coat of arms.[17]

Treaty of Tordesillas (1494)

The possibility of a sea route around Africa to India and the rest of Asia would open enormous opportunities to trade for Portugal, so it aggressively pursued the establishment of both trade outposts and fortified bases.

Knowing that Indian Ocean connected the Atlantic Ocean (Bartolomeu Dias' voyage of 1488), King John II of Portugal refused support to Christopher Columbus's offer to reach India by sailing west across the Atlantic Ocean. Columbus next turned successfully to Queen Isabella of Castile, and his unintended discovery of the West Indies led to the establishment of the Spanish Empire in the Americas.

The Portuguese Empire was guaranteed by the papal bull of 1493 and the Treaty of Tordesillas of 6 June 1494. These two actions (and related bulls and treaties) divided the world outside of Europe in an exclusive duopoly between the Portuguese and the Spanish. The dividing line in the Western Hemisphere was established along a north-south meridian 370 leagues (1550 km; 970 miles) west of the Cape Verde islands (off the west coast of Africa), at roughly 46° west longitude. A similar antipodal line in the Eastern Hemisphere was established by the Treaty of Saragossa. As a result, all of Africa and almost all of Asia would belong to Portugal, while almost all of the New World would belong to Spain.

The Pope's initial proposal of the line was moved a little west by John II, and it was accepted. However, the new line granted Brazil and (thought at that time) Newfoundland to Portugal both in 1500. As the distance proposed by John II is not "round" (370 leagues), some see the evidence that Portugal knew the existence of those lands before the Treaty of Tordesillas (1494). John II died one year later, in 1495.

Height of Empire (1494-1580)

With the Treaty of Tordesillas signed, Portugal assured exclusive navigation around Africa and, in 1498, Vasco da Gama reached India and established the first Portuguese outposts there. Soon Portugal become the center of the commerce with the East.

In East Africa, small Islamic states along the coast of Mozambique, Kilwa, Brava, Sofala and Mombasa were destroyed, or became either subjects or allies of Portugal. Pêro da Covilhã had reached Ethiopia, travelling secretly overland, as early as 1490; a diplomatic mission reached the ruler of that nation on October 19, 1520. Explorer Pedro Álvares Cabral, on April 22, 1500, landed in what is today Porto Seguro, Brazil and temporary trading posts were established to collect brazilwood for use as a dye. In the Arabian Sea, Socotra was occupied in 1506, and in the same year Lourenço d'Almeida visited Ceylon(Modern day Sri Lanka)(see Portuguese Ceylon). Aden, after the failed conquest of 1510, was conquered in 1516. In the Indian Ocean, one of Pedro Álvares Cabral's ships discovered Madagascar, which was partly explored by Tristão da Cunha in 1507, the same year Mauritius was discovered. In 1509, the Portuguese won the sea Battle of Diu against the combined forces of the Ottoman Sultan Beyazid II, Sultan of Gujarat, Mamlûk Sultan of Cairo, Samoothiri Raja of Kozhikode, Venetian Republic, and Ragusan Republic (Dubrovnik). A second Battle of Diu in 1538 finally ended Ottoman ambitions in India and confirmed Portuguese hegemony in the Indian Ocean.

Portugal established trading ports at far-flung locations like Goa, Ormuz, Malacca, Kochi, the Maluku Islands, Macau, and Nagasaki. Guarding its trade from both European and Asian competitors, Portugal dominated not only the trade between Asia and Europe, but also much of the trade between different regions of Asia, such as India, Indonesia, China, and Japan. Jesuit missionaries, such as the Basque Francis Xavier, followed the Portuguese to spread Roman Catholic Christianity to Asia with mixed success.

The Portuguese empire expanded from the Indian Ocean into the Persian Gulf as Portugal contested control of the spice trade with the Ottoman Empire. In 1515, Afonso de Albuquerque conquered the Huwala state of Hormuz at the head of the Gulf, establishing it as a vassal state, before capturing Bahrain in 1521, when a force led by Antonio Correia defeated the Jabrid King, Muqrin ibn Zamil.[18] In a shifting series of alliances, the Portuguese dominated much of the southern Gulf for the next hundred years.

While Portuguese ships explored Asia and South America, King Manuel I of Portugal gave permission to explore the North Atlantic to João Fernandes "Lavrador" in 1499[19] (however he may already explored some lands as early as 1492, as it is suggested by one letter by Pêro de Barcelos[20]) and to the Corte-Real brothers in 1500 and 1501. Lavrador rediscovered Greenland and probably explored Labrador (named after him) and Miguel and Gaspar Corte-Real explored Newfoundland and Labrador, and possibly most of, if not all, the east coast of Baffin Island.[21] In 1516 João Álvares Fagundes explored the North tip of Nova Scotia and islands from its coast to the south coast of Newfoundland. In 1521 Fagundes received the captaincy of the lands he discovered and the authorization to build a colony.[22] His possessions were also distinguished from the Corte-Real's lands. The Corte-Real family, that possessed the Lordship of Terra Nova also attempted colonization. In 1567 Manuel Corte-Real sent 3 ships to colonise his North American land.[23] The colony in Cape Breton (Fagundes' one) is mentioned as late as 1570[24] and the last confirmation of the title of Lord of Terra Nova was issued in 1579 by King Henry to Vasco Annes Corte-Real,[25] son of Manuel (and not the brother of Gaspar and Miguel, with the same name). The interest in North America faded as the African and Asiatic possessions were more wealthy and the personal union of Portugal and Spain may have led to the end of the Portuguese colonies in North America. As of 2008, no trace was found of any Portuguese colony in North America.

In 1503, an expedition under the command of Gonçalo Coelho found the French making incursions on the land that is today Brazil. John III, in 1530, organized the colonization of Brazil around 15 capitanias hereditárias ("hereditary captainships"), that were given to anyone who wanted to administer and explore them. That same year, there was a new expedition from Martim Afonso de Sousa with orders to patrol the whole Brazilian coast, banish the French, and create the first colonial towns: São Vicente on the coast, and São Paulo on the border of the altiplane. From the 15 original captainships, only two, Pernambuco and São Vicente, prospered. With permanent settlement came the establishment of the sugar cane industry and its intensive labor demands which were met with Native American and later African slaves. Deeming the capitanias system ineffective, Tomé de Sousa, the first Governor-General was sent to Brazil in 1549. He built the capital of Brazil, Salvador at the Bay of All Saints. The first Jesuits arrived the same year.

Some historians argue that it was Portuguese sailors that were the first Europeans to discover Australia,[26][27] exploring from their bases in East Asia. This view is based on reinterpretations of maps from the period, but remains contentious (see Theory of Portuguese discovery of Australia).

From 1565 through 1567 Mem de Sá, a Portuguese colonial official and the third Governor General of Brazil, successfully destroyed a ten year-old French colony called France Antarctique, at Guanabara Bay. He and his nephew, Estácio de Sá, then founded the city of Rio de Janeiro in March 1567.

In 1578, the Portuguese crusaders crossed into Morocco and were routed by Ahmed Mohammed of Fez, at the Alcazarquivir (Now : Ksar-el-Kebir) also known as "the battle of the Three Kings". King Sebastian of Portugal was almost certainly killed in battle or subsequently executed. The Crown was handed over to his uncle Henry of Portugal but he died in 1580 without heirs. King Philip II of Spain who was one of the closest dynastic claimants to the throne, invaded the country with his troops under the command of the Duke of Alba and was proclaimed King of Portugal by the Portuguese Cortes.

Union with Spain (1580-1640)

From 1580 to 1640, the throne of Portugal was held by the Habsburg kings of Spain resulting in the most extensive colonial empire until then (see Iberian Union). In 1583 Philip I of Portugal, II of Spain, sent his combined Iberian fleet to clear the French traders from the Azores, decisively hanging his prisoners-of-war from the yardarms and contributing to the "Black Legend". The Azores were the last part of Portugal to resist Philip's reign over Portugal.

Portuguese colonization was not successful in the Persian Gulf. Gamru Port and Hormuz were occupied by Portuguese by 1615. In 1622 Abbas I of Persia engaged the Portuguese in battle with the aid of the English Navy and the British East India Company. The Gamru was renamed Bandar Abbas after the Portuguese evacuated.

In the Americas, the Portuguese expansion continued beyond the west side by the meridian set by the Treaty of Tordesillas. Portugal was able to mount a military expedition that defeated and expelled the French colonists of France Équinoxiale in 1615, less than four years after their arrival in the land. The Dutch Republic captured and sacked the Portuguese outpost of Salvador da Bahia in May of 1624, and held it along with other north east ports until it was re-taken on April 30 1625 by a fleet under the command of Fradique de Toledo. The fleet was composed of 22 Portuguese ships, 34 Spanish ships and 12,500 men (three quarters were Spanish and the rest were Portuguese).

However, in 1627 the Castilian economy collapsed. The Dutch, who during the Twelve Years' Truce had made their navy a priority, devastated Spanish maritime trade after the resumption of war, on which Spain was wholly dependent after the economic collapse. Even with a number of victories, Spanish resources were now fully stretched across Europe and also at sea protecting their vital shipping against the greatly improved Dutch fleet. Spain's enemies, such as the Netherlands and England, coveted its overseas wealth, and in many cases found it easier to attack poorly-defended Portuguese outposts than Spanish ones. Thus the Dutch-Portuguese War began.

Between 1638 and 1640, the Netherlands came to control part of Brazil's Northeast region, with their capital in Recife. The Portuguese won a significant victory in the Second Battle of Guararapes in 1649. By 1654, the Netherlands had surrendered and returned control of all Brazilian-occupied land to the Portuguese.

Although Dutch colonies in Brazil were wiped out, during the course of the 17th century the Dutch were able to occupy Ceylon, the Cape of Good Hope, the East Indies, part of India and to take over the trade with Japan at Nagasaki. Portugal's Asiatic territories were reduced to bases at Macau, East Timor and Portuguese India.

Imperial decline (1640-1822)

The loss of colonies was one of the reasons that contributed to the end of the personal union with Spain. In 1640 John IV was proclaimed King of Portugal and the Portuguese Restoration War began. In 1668 Spain recognized the end of the Iberian Union and in exchange Portugal ceded Ceuta to the Spanish crown.

In 1661 the Portuguese offered Bombay and Tangier to England as part of a dowry, and over the next hundred years the British gradually became the dominant trader in India, providing the bases from which its empire would grow as the Moghul Empire disintegrated from the middle of the 18th century, gradually excluding the trade of other powers in the later 18th and early 19th centuries. Portugal was able to cling onto Goa and several minor bases through the remainder of the colonial period, but their importance declined as trade was diverted through increasing numbers of English, Dutch and French trading posts.

In 1755 Lisbon suffered a catastrophic earthquake, which together with a subsequent tsunami killed more than 100,000 people out of a population of 275,000. This sharply checked Portuguese colonial ambitions in the late 18th century.

Unlike Spain, Portugal did not divide its colonial territory in America. The captaincies created there were subordinated to a centralized administration in Salvador which reported directly to the Crown in Lisbon.

Encouraged by the example of the United States of America, which had won its independence from Britain, an attempt was made in 1789 to achieve the same in Brazil. The Inconfidência Mineira failed, the leaders arrested and, of the participants of the insurrections the one of lowest social position, Tiradentes, was hanged.

In 1808, Napoleon Bonaparte invaded Portugal, and Dom João, prince regent in place of his mother, Dona Maria I, ordered the transfer of the royal court to Brazil. In 1815 Brazil was elevated to the status of Kingdom, the Portuguese state officially becoming the United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil and the Algarves (Reino Unido de Portugal, Brasil e Algarves), and the capital was transferred from Lisbon to Rio de Janeiro. There was also the election of Brazilian representatives to the Cortes Constitucionais Portuguesas (Portuguese Constitutional Courts).

Dom João, fleeing from Napoleon's army, moved the seat of government to Brazil in 1808. Brazil thereupon became a kingdom under Dom João VI, and the only instance of a European country being ruled from one of its colonies. Although the royal family returned to Portugal in 1821, the interlude led to a growing desire for independence amongst Brazilians. In 1822, the son of Dom João VI, then prince-regent Dom Pedro I, proclaimed the independence, September 7, 1822, and was crowned emperor. Unlike the Spanish colonies of South America, Brazil's independence was achieved without significant bloodshed.

Portuguese Africa and the overseas provinces (1822–1961)

At the height of European colonialism in the 19th century, Portugal had lost its territory in South America and all but a few bases in Asia. During this phase, Portuguese colonialism focused on expanding its outposts in Africa into nation-sized territories to compete with other European powers there. Portuguese territories eventually included the modern nations of Cape Verde, São Tomé and Príncipe, Guinea-Bissau, Angola, and Mozambique.

Portugal pressed into the hinterland of Angola and Mozambique, and explorers Serpa Pinto, Hermenegildo Capelo and Roberto Ivens were among the first Europeans to cross Africa west to east. The project to connect the two colonies, the Pink Map, was the Portuguese main objective in the second half of the 19th century. However, the idea was unacceptable to the British, who had their own aspirations of contiguous British territory running from Cairo to Cape Town. The British Ultimatum of 1890 was respected by King Carlos I of Portugal and the Pink Map came to an end. The King's reaction to the ultimatum was exploited by republicans. In 1908 King Carlos and Prince Luís Filipe were murdered in Lisbon. Luís Filipe's brother, Manuel, become King Manuel II of Portugal. Two years later Portugal became a republic.

In World War I German troops threatened Mozambique, and Portugal entered the war to protect its colonies.

António de Oliveira Salazar, who had seized power in 1933, considered Portuguese colonies as overseas provinces of Portugal. In the wake of World War II, the decolonization movements began to gain momentum. In the Portuguese Empire the first major clash occurred in São Tomé in the Batepá massacre of 1953. The Cold War also created instabilities among Portuguese overseas populations, as the United States and Soviet Union tried to increase their spheres of influence. In 1954 India invaded Dadra and Nagar Haveli, and in 1961 Portuguese India come to an end when Goa, Daman and Diu were also invaded.[1] [2] Also in 1961 the tiny Portuguese fort of São João Baptista de Ajudá in Ouidah, a remnant of the West African slave trade, was taken by the new government of Dahomey (now Benin).

But, despite these losses and unlike the other European colonial powers, Salazar attempted to resist the tide of decolonization and maintain the integrity of the empire. As a result, Portugal was the last nation to retain its major colonies.

End of empire (1961-1999)

The rise of pro-communist influence among the Movimento das Forças Armadas's military (MFA) and working class, and the cost and unpopularity of the Portuguese Colonial War (1961-1974), in which Portugal resisted to the emerging nationalist guerrilla movements in some of its African territories, eventually led to the collapse of the Estado Novo regime in 1974. Known as the "Carnation Revolution", one of the first acts of the MFA-led government which then came into power - the National Salvation Junta (Junta de Salvação Nacional) - was to end the wars and negotiate Portuguese withdrawal from its African colonies. These events prompted a mass exodus of Portuguese citizens from Portugal's African territories (mostly from Angola and Mozambique), creating over a million Portuguese refugees - the retornados.[28] Portugal's new ruling authorities also recognized Goa and other Portuguese India's territories invaded by India's military forces, as Indian territories. Benin's claims over São João Baptista de Ajudá, were also accepted by the Portuguese, and diplomatic relations were restored with both India and Benin.

Civil wars in both independent Mozambique and Angola promptly broke out, with incoming communist governments formed by the former rebels (and backed by the Soviet Union, Cuba, and other communist countries) fighting against insurgent groups supported by nations like Zaire, South Africa, and the United States.

East Timor also declared independence at this time (1975), but was almost immediately invaded by neighbouring Indonesia, which occupied it until 1999. A United Nations-sponsored referendum that year resulted in East Timorese choosing independence, which was achieved in 2002.

The handover of Macau to China in 1999 under the terms of an agreement negotiated between People's Republic of China and Portugal twelve years earlier marked the end of the Portuguese overseas empire.

Legacy

The seven former colonies of Portugal that are now independent nations with Portuguese as their official language, together with Portugal, are members of the Community of Portuguese Language Countries. Today portuguese is one of the world's major languages, ranked 6th according to number of native speakers (between 177 and 191 million). It is the language of about half of South America, even though Brazil is the only Portuguese-speaking nation in the Americas. It is also a major lingua franca in Portugal's former colonial possessions in Africa. It is an official language in eight countries , also being co-official with Cantonese Chinese in the Chinese special administrative region of Macau.

See also

- Portugal

- Kingdom of Portugal

- Economic history of Portugal

- Global empire

- Colonial Brazil

- History of Portugal

- Timeline of Portuguese history

- Evolution of the Portuguese Empire

- Portuguese people

- Portuguese language

- Bahrain as a Portuguese dominion

- United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil and the Algarves

- Portuguese West Africa

- Portuguese East Africa

Notes

- ^ Newitt, p. 19

- ^ Boxer, p. 19

- ^ Newitt, p. 19

- ^ Abernethy, p. 4

- ^ Newitt, p. 21

- ^ Diffie, p. 55

- ^ Diffie, p. 55

- ^ Diffie, p. 56

- ^ Anderson, p. 50

- ^ Boxer, p. 19

- ^ Diffie, p. 57—58

- ^ Diffie, p. 60

- ^ Diffie, p. 68

- ^ Anderson, p. 44

- ^ Boxer, p. 29

- ^ McAlister, p. 66

- ^ Newitt, p. 47

- ^ Juan Cole, Sacred Space and Holy War, IB Tauris, 2007 p37

- ^ Archivo Nacional da Torre do Tombo, Livro XVI de D. Manuel, f. 39 vº

- ^ CANTO, Ernesto do, Quem deu o nome ao Labrador?, 1893

- ^ Archivo dos Açores, Os Corte-Reaes, Capítulo III, p. 430-431

- ^ BETTENCOURT, E. A. de, Hist. dos descobrimentos, guerras e conquistas dos portuguezes, em terras do ultramar nos séculos XV e XVI, p. 132-135

- ^ Archivo Nacional da Torre do Tombo, Livro 6 dos Privilégios de D. Sebastião, f.237

- ^ SOUZA, Francisco de, Tratado das Ilhas Novas, 1570

- ^ Archivo Nacional da Torre do Tombo, Livro 3 das Conf. Ger., f. 277 vº

- ^ Kenneth Gordon McIntyre, The Secret Discovery of Australia (1977)

- ^ Peter Trickett, Beyond Capricorn (2007)

- ^ Dismantling the Portuguese Empire, Time Magazine (Monday, Jul. 07, 1975)

References

- Abernethy, David (2000). The Dynamics of Global Dominance, European Overseas Empires 1415-1980. Yale University Press. ISBN 0300093144.

- Anderson, James Maxwell (2000). The History of Portugal. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0313311064.

- Boxer, C.R. (1969). The Portuguese Seaborne Empire 1415–1825. Hutchinson. ISBN 0091310717.

- Diffie, Bailey (1977). Foundations of the Portuguese Empire, 1415-1580. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 0816607826.

- McAlister, Lyle (1984). Spain and Portugal in the New World, 1492-1700. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 0816612161.

- Newitt, M.D.D. (2005). A History of Portuguese Overseas Expansion, 1400-1668. Routledge. ISBN 0415239796.

- Russell-Wood, A.J.P. The Portuguese Empire 1415-1825

- Allen K 1954 The Portuguese Empire and its defeat vol1 pp224-234

General

External links

- Portuguese Empire Timeline

- Japanese Screen Painting of the Portuguese in the Indies (Enlarge)

- Dutch Portuguese Colonial History Dutch Portuguese Colonial History: history of the Portuguese and the Dutch in Ceylon, India, Malacca, Bengal, Formosa, Africa, Brazil. Language Heritage, lists of remains, maps.

- The Portuguese and the East (in Portuguese, Chinese, Japanese and Thai) with English introduction.

- Sizes of the largest Empires in History:"To Rule the Earth"

- The First Global Village by Martin Page