पाटलिपुत्र (talk | contribs) |

|||

| Line 19: | Line 19: | ||

===1200-1210 edition (BNF Arabe 3929)=== |

===1200-1210 edition (BNF Arabe 3929)=== |

||

An edition dating to the early 13th century exists at the [[Bibliothèque Nationale de France]] ([[:Commons:Category:Maqamat of al-Hariri - BNF Arabe3929|Arabe 3929]]).<ref>{{cite web |title=Consultation Arabe 3929 |url=https://archivesetmanuscrits.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/cc31686q |website=archivesetmanuscrits.bnf.fr}}</ref> This edition may be [[Artuqid]]. |

An edition dating to the early 13th century exists at the [[Bibliothèque Nationale de France]] ([[:Commons:Category:Maqamat of al-Hariri - BNF Arabe3929|Arabe 3929]]).<ref>{{cite web |title=Consultation Arabe 3929 |url=https://archivesetmanuscrits.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/cc31686q |website=archivesetmanuscrits.bnf.fr}}</ref> This edition may be [[Artuqid]].{{sfn|Contadini|2012|p=120, fig. 45}} It was probably manufactured in Amid, modern-day [[Diyarbakır]], Turkey, ca. 1200–1210.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Balafrej |first1=Lamia |title=Automated Slaves, Ambivalent Images, and Noneffective Machines in al-Jazari's Compendium of the Mechanical Arts, 1206. |journal=Inquiries into Art |date=19 December 2022 |volume=History |page=766, Fig.11 |doi=10.11588/xxi.2022.4.91685 |url=https://journals.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/index.php/xxi/article/download/91685/87635}}</ref> This manuscript probably belongs to the "[[Artuqids|Artuqid school]]" of painting, together with an early 1206 edition of the ''Automata'' of [[Ibn al-Razzaz al-Jazari]], devoted to the depiction of mechanical devices ([[:Commons:Category:Al-Jazari (Ms. Ahmet III 3472)|Ahmet III 3472]], [[Topkapı Sarayı Library]], securely dated to 1206 and displaying many design similarities).<ref name="LB">{{cite journal |last1=Balafrej |first1=Lamia |title=Automated Slaves, Ambivalent Images, and Noneffective Machines in al-Jazari's Compendium of the Mechanical Arts, 1206. |journal=Inquiries into Art |date=19 December 2022 |volume=History |pages=739-741 |doi=10.11588/xxi.2022.4.91685 |url=https://journals.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/index.php/xxi/article/download/91685/87635}}</ref><ref name="RW2">{{cite journal |last1=Ward |first1=Rachel |title=Evidence for a School of Painting at the Artuqid Court |journal=Oxfod Studies in Islamic Art, vol. 1, pp. 69-83 |date=1 January 1985 |pages=76-77 |url=https://www.academia.edu/42857318/Evidence_for_a_School_of_Painting_at_the_Artuqid_Court}}</ref> |

||

This illustrated manuscript is considered as the most ancient ''Maqamat'' known. The illustrations are rather simple and literal, which leads most specialists to attribute this manuscript to the early 13th or even late 12th century.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Sakkal |first1=Aya |title=La représentation du héros des Maqāmāt |

This illustrated manuscript is considered as the most ancient ''Maqamat'' known. The illustrations are rather simple and literal, which leads most specialists to attribute this manuscript to the early 13th or even late 12th century.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Sakkal |first1=Aya |title=La représentation du héros des Maqāmāt d'al-Ḥarīrī dans les trois premiers manuscrits illustrés |journal=Annales islamologiques |date=25 August 2014 |issue=48.1 |pages=79–102 |doi=10.4000/anisl.3080 |url=https://journals.openedition.org/anisl/3080?lang=ar |language=fr |issn=0570-1716 |quote=Most of the illustrations are simple and at first glance quite literal, and for this reason most scholars have assigned the manuscript to the early thirteenth century, or even to the late twelfth. A more sophisticated discussion by Rice of one group of illustrations led him to a date sometime in the 1240. (Grabar, The Illustrations of the Maqamat, p. 8.)}}</ref> |

||

The first pages are lost, and the manuscript only starts from the second story (second ''Maqamah'').{{sfn|Grabar|1984|p=8}} |

The first pages are lost, and the manuscript only starts from the second story (second ''Maqamah'').{{sfn|Grabar|1984|p=8}} |

||

| Line 29: | Line 29: | ||

File:Arabe 3929, 117r.jpg|Arabe 3929, 117r |

File:Arabe 3929, 117r.jpg|Arabe 3929, 117r |

||

File:Maqamat Arabe 3929, Abu Zaid before the Cadi (detail) 157r.jpg|Arabe 3929, 157r: ruler in Turkic dress wearing the ''[[sharbūsh]]'' with the tall cap |

File:Maqamat Arabe 3929, Abu Zaid before the Cadi (detail) 157r.jpg|Arabe 3929, 157r: ruler in Turkic dress wearing the ''[[sharbūsh]]'' with the tall cap |

||

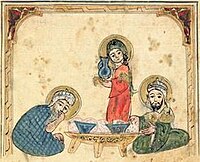

File:Arabe 3929, 151, Jariya.jpg|A ''[[Jarya|Jariya]]'' prostitute.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Balafrej |first1=Lamia |title=Automated Slaves, Ambivalent Images, and Noneffective Machines in al- |

File:Arabe 3929, 151, Jariya.jpg|A ''[[Jarya|Jariya]]'' prostitute.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Balafrej |first1=Lamia |title=Automated Slaves, Ambivalent Images, and Noneffective Machines in al-Jazari's Compendium of the Mechanical Arts, 1206. |journal=Inquiries into Art |date=19 December 2022 |volume=History |page=768 |doi=10.11588/xxi.2022.4.91685 |url=https://journals.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/index.php/xxi/article/download/91685/87635}}</ref> |

||

</gallery> |

</gallery> |

||

===1222 edition (BNF Arabe 6094)=== |

===1222 edition (BNF Arabe 6094)=== |

||

The 1222 edition is an illuminated manuscript, now in the [[Bibliothèque nationale de France]] in Paris (BNF Arabe 6094).<ref>{{cite web |title=Makamat de Hariri 6094 |url=https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b8422967h/f147.item.zoom# |language=EN |date=1222}}</ref> It was made in the [[Upper Mesopotamia|Jazira]] region, and is the earliest securely dated ''Maqamat'' by al-Hariri.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Sakkal |first1=Aya |title=La représentation du héros des Maqāmāt |

The 1222 edition is an illuminated manuscript, now in the [[Bibliothèque nationale de France]] in Paris (BNF Arabe 6094).<ref>{{cite web |title=Makamat de Hariri 6094 |url=https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b8422967h/f147.item.zoom# |language=EN |date=1222}}</ref> It was made in the [[Upper Mesopotamia|Jazira]] region, and is the earliest securely dated ''Maqamat'' by al-Hariri.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Sakkal |first1=Aya |title=La représentation du héros des Maqāmāt d'al-Ḥarīrī dans les trois premiers manuscrits illustrés |journal=Annales islamologiques |date=25 August 2014 |issue=48.1 |pages=79–102 |doi=10.4000/anisl.3080 |url=https://journals.openedition.org/anisl/3080?lang=ar#tocto1n2 |language=fr |issn=0570-1716}}</ref> The style and numerous Byzantine inspirations in the illustrations also suggest it might have been drawn in the area of Damascus in Syria, under the rule of the [[Ayyubids]].{{sfn|Grabar|1984|p=9}} The date appears in several places (on the hull of the boat in folio 68, or a plate held by a schoolboy in folio 167, in the format "made in the year 619" i.e. 1222 CE).{{sfn|Grabar|1984|p=9}} |

||

<gallery widths="200px" heights="200px" perrow="4"> |

<gallery widths="200px" heights="200px" perrow="4"> |

||

File:Maqamat 1222 6r.jpg|Maqamat 1222, 6r |

File:Maqamat 1222 6r.jpg|Maqamat 1222, 6r |

||

| Line 60: | Line 60: | ||

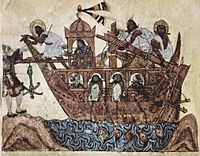

File:Maqamat 5847, f.119v- maqama 39 Abu Zayd and al-Harith sailing.jpg|''A ship bound for Oman'' (Maqāma 39).{{sfn|Shah|1980|pp=193-198|loc=Maqāma 39, "The encounter at Oman"}} |

File:Maqamat 5847, f.119v- maqama 39 Abu Zayd and al-Harith sailing.jpg|''A ship bound for Oman'' (Maqāma 39).{{sfn|Shah|1980|pp=193-198|loc=Maqāma 39, "The encounter at Oman"}} |

||

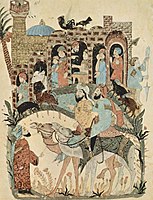

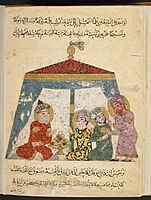

File:Yahyâ ibn Mahmûd al-Wâsitî 001.jpg|[[Ayyubid]] Governor of [[Rahba]], with Abū Zayd and his son.{{sfn|Contadini|2012|p=143}} |

File:Yahyâ ibn Mahmûd al-Wâsitî 001.jpg|[[Ayyubid]] Governor of [[Rahba]], with Abū Zayd and his son.{{sfn|Contadini|2012|p=143}} |

||

File:Turkic guard in Preaching scene at Rayy in maqāma 21 (fols. 58v–59r, douvle-page spread as a unit), Maqamat al-Harari 1237.jpg|Turkic amir with guards, wearing the Turkic headgear ''[[Sharbush]]'', in the preaching scene at [[Ray, Iran|Rayy]], Iran,{{sfn|Hillenbrand|2010|p=118, note 10}}<ref name="AC">{{ |

File:Turkic guard in Preaching scene at Rayy in maqāma 21 (fols. 58v–59r, douvle-page spread as a unit), Maqamat al-Harari 1237.jpg|Turkic amir with guards, wearing the Turkic headgear ''[[Sharbush]]'', in the preaching scene at [[Ray, Iran|Rayy]], Iran,{{sfn|Hillenbrand|2010|p=118, note 10}}<ref name="AC">{{harvnb|Contadini|2012|p=126–127}}: "Official" Turkish figures wear a standard combination of a sharbūsh, a three-quarters length robe, and boots. Arab figures, in contrast, have different headgear (usually a turban), a robe that is either full-length or, if three-quarters length, has baggy trousers below, and they usually wear flat shoes or (...) go barefoot (...) P.127: Reference has already been made to the combination of boots and ''[[sharbūsh]]'' as markers of official status (...) the combination is standard, even being reflected in thirteenth-century Coptic paintings, and serves to distinguish, in Grabar's formulation, the world of the Turkish ruler and that of the Arab. (...) The type worn by the official figures in the 1237 Maqāmāt, depicted, for example, on fol. 59r,67 consists of a gold cap surmounted by a little round top and with fur trimming creating a triangular area at the front which either shows the gold cap or is a separate plaque. A particular imposing example in this manuscript is the massive ''sharbūsh'' with much more fur than usual that is worn by the princely official on the right frontispiece on fol. 1v."</ref> , in maqāma 21 (fols. 58v–59r).{{sfn|Shah|1980|pp=84-88|loc=Maqāma 21, "The encounter at Rayy al-Mahdiyeh"}} |

||

</gallery> |

</gallery> |

||

| Line 78: | Line 78: | ||

File:British Library, Ms. Or. 1200 folio 2.jpg|British Library, Ms. Or. 1200 |

File:British Library, Ms. Or. 1200 folio 2.jpg|British Library, Ms. Or. 1200 |

||

File:British Library, Ms. Or. 1200 folio 3.jpg|British Library, Ms. Or. 1200 |

File:British Library, Ms. Or. 1200 folio 3.jpg|British Library, Ms. Or. 1200 |

||

File:Abū Zayd in the |

File:Abū Zayd in the children's school (al-Ḥarīrī, Maqāmāt, 654.1256). The British Library Board, or. 1200, fol. 156v.jpg|Abū Zayd in the children's school. British Library, Ms. Or. 1200 |

||

</gallery> |

</gallery> |

||

| Line 86: | Line 86: | ||

<gallery widths="200px" heights="200px" perrow="4"> |

<gallery widths="200px" heights="200px" perrow="4"> |

||

File:Maqamat, Syria, late 13th-century, British Library, Ms. Or. 9718 Two camel riders in Arab bedouin costumes.jpg|Two camel riders in Arab bedouin costumes. Maqamat, Syria, late 13th-century, British Library, Ms. Or. 9718. |

File:Maqamat, Syria, late 13th-century, British Library, Ms. Or. 9718 Two camel riders in Arab bedouin costumes.jpg|Two camel riders in Arab bedouin costumes. Maqamat, Syria, late 13th-century, British Library, Ms. Or. 9718. |

||

File:Abū Zayd in the |

File:Abū Zayd in the children's school. Britiah Library 9718.jpg|Abū Zayd in the children's school. British Library, Ms. Or. 9718. |

||

</gallery> |

</gallery> |

||

| Line 154: | Line 154: | ||

== Sources == |

== Sources == |

||

* {{cite book |last1=Contadini |first1=Anna |title=A World of Beasts: A Thirteenth-Century Illustrated Arabic Book on Animals (the Kitāb |

* {{cite book |last1=Contadini |first1=Anna |title=A World of Beasts: A Thirteenth-Century Illustrated Arabic Book on Animals (the Kitāb Na't al-Ḥayawān) in the Ibn Bakhtīshū' Tradition |date=1 January 2012 |doi=10.1163/9789004222656_005 |publisher=Brill |url=https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004222656_005}} |

||

* {{Cite book |last=Ettinghausen |first=Richard |title=La Peinture arabe |publisher=Skira |year=1977 |location=Geneva |pages=104–124 |language=fr}} |

* {{Cite book |last=Ettinghausen |first=Richard |title=La Peinture arabe |publisher=Skira |year=1977 |location=Geneva |pages=104–124 |language=fr}} |

||

* {{cite book |last1=Grabar |first1=Oleg |title=The Illustrations of the Maqamat |date=1984 |publisher=University of Chicago Press |page=7 |url=https://www.islamicmanuscripts.info/reference/books/Grabar-1984-Maqamat-illustrations.pdf}} |

* {{cite book |last1=Grabar |first1=Oleg |title=The Illustrations of the Maqamat |date=1984 |publisher=University of Chicago Press |page=7 |url=https://www.islamicmanuscripts.info/reference/books/Grabar-1984-Maqamat-illustrations.pdf}} |

||

Revision as of 08:28, 21 January 2024

The Maqamat al-Hariri (Arabic: مقامات الحريري) is a collection of 50 tales or maqamat written at the end of the 11th or the beginning of the 12th century by al-Hariri of Basra (1054–1122), a poet and government official of the Seljuk Empire.[2] The first known manuscripts date to the 13th-century, with eight illustrated manuscripts known from this period. The most famous manuscripts include one from 1237 in Baghdad (now in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France) and one from 1334 in Egypt or Syria (now in Vienna).[3]

Altogether, more than a hundred Maqamat manuscripts are know, but only 13 are illustrated. They mainly cover a period of about 150 years.[4] A first phase consists in manuscripts created between 1200 and 1256 in areas between Syria and Iraq. This phase is followed by a 50-year gap, corresponding to the Mongol invasions (invasion of Persia and Mesopotamia, with the Siege of Baghdad in 1258, and the invasion of the Levant). A second phase runs from around 1300 to 1337, during the Egyptian Mamluk period, with production probably centered around Cairo.[5]

Manuscripts

Early non-illustrated editions

Several early non-illustrated editions of the Maqamat al-Hariri are known. The earliest known manuscript is "Ms. Cairo Adab 105", dated 504/1110-11 through an ijaza certificate of authenticity by al-Hariri himself. It is by far the earliest the earliest known manuscript, and it was copied the same year al-Hariri completed his work.[8]

Other early manuscripts are known, such as "London, British Library, Or. 2790" dated 557 AH/1161-62 CE; "Vatican, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Sbath 265", dated 583 AH/1187 CE; "Paris, BnF, Arabe 3924", dated 584 AH/1188 CE; "Paris, BnF, Arabe 3926", dated 611 AH/1214 CE; "Paris, BnF, Arabe 3927", dated 611 AH/1214 CE.

Although probably less creative than the work of his predecessor al-Hamadhani (968–1008 CE), the Maqamat al-Hariri became extremely popular, with reports of seven hundred copies authorized by al-Hariri during his lifetime.[9]

After this initial non-illustrative phase, illustrated Maqamat manuscripts then started to appear, corresponding to a broader "explosion of figural art" in the Islamic world, from the 12th to 13th centuries, despite religious condemnations against the depiction of living creatures "because it implies a likeness to the creative activity of God".[10]

1200-1210 edition (BNF Arabe 3929)

An edition dating to the early 13th century exists at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France (Arabe 3929).[11] This edition may be Artuqid.[12] It was probably manufactured in Amid, modern-day Diyarbakır, Turkey, ca. 1200–1210.[13] This manuscript probably belongs to the "Artuqid school" of painting, together with an early 1206 edition of the Automata of Ibn al-Razzaz al-Jazari, devoted to the depiction of mechanical devices (Ahmet III 3472, Topkapı Sarayı Library, securely dated to 1206 and displaying many design similarities).[14][15]

This illustrated manuscript is considered as the most ancient Maqamat known. The illustrations are rather simple and literal, which leads most specialists to attribute this manuscript to the early 13th or even late 12th century.[16]

The first pages are lost, and the manuscript only starts from the second story (second Maqamah).[17]

-

Arabe 3929, 7v

-

Arabe 3929, 117r

-

Arabe 3929, 157r: ruler in Turkic dress wearing the sharbūsh with the tall cap

1222 edition (BNF Arabe 6094)

The 1222 edition is an illuminated manuscript, now in the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris (BNF Arabe 6094).[19] It was made in the Jazira region, and is the earliest securely dated Maqamat by al-Hariri.[20] The style and numerous Byzantine inspirations in the illustrations also suggest it might have been drawn in the area of Damascus in Syria, under the rule of the Ayyubids.[21] The date appears in several places (on the hull of the boat in folio 68, or a plate held by a schoolboy in folio 167, in the format "made in the year 619" i.e. 1222 CE).[21]

-

Maqamat 1222, 6r

-

Maqamat 1222, 31r

-

Maqamat 1222, 167r. Students, some wearing the Arab turban, others Turkic caps.[23]

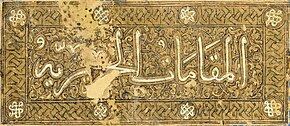

1237 edition (BNF Arabe 5847)

The 1237 edition is an illuminated manuscript created by Yahya ibn Mahmud al-Wasiti in 1237. This is probably the most applauded edition of the Maqamat.[24] It may have been created in Baghdad, based on some stylistic parallels with the Kitab al-baytarah which securely emanated from this city, but this attribution remains quite conjectural.[25] Still the name of the Abbasid Caliph al-Mustansir appears in one of the paintings (fol. 164v), which does create a certain connection.[26]

This maqama manuscript is currently kept in the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris (BNF Arabe 5847).[27] It is also known as the Schefer Ḥarīrī.[28]

According to its colophon, the manuscript was copied in the year 634 of the Islamic calendar (equivalent to 1237 in the Western calendar).[29][30] The manuscript details a series of tales regarding the adventures of the fictional character Abu Zayd of Saruj who travels and deceives those around him with his skill in the Arabic language to earn rewards.[31]

The twin frontispieces show one individual in Arab dress, who may be the author himself, and a majestic ruler in Seljuk-type Turkic military dress (long braids, fur hat, boots, fitting coat), who may be the potentate the manuscript was dedicated to.[2][32][33]

The book is written in red and black ink, and supplemented by 99 miniatures.[29] These miniatures depict a wide variety of scenes from the Maqamat and from every day life. Most are decorated with gold.[25]

-

Assembly

-

Childbirth in a foreign land

-

A conversation near a city

-

A ship bound for Oman (Maqāma 39).[34]

1242-1258 edition (Suleymaniye, Esad Efendi 2961)

This manuscript is badly damaged and all the faces were erased.[38] Its colophon bears a dedication to Abbasid Caliph Al-Musta'sim (1243-1258), but location is unknown.[38][26]

-

Suleymaniye Library, Esad Efendi 2916

-

Suleymaniye Library, Esad Efendi 2916

-

Suleymaniye Library, Esad Efendi 2916

-

Suleymaniye Library, Esad Efendi 2916

1256 edition (British Library, Ms. Or. 1200)

This manuscript has a colophon describing the date of its manufacture as 1256.[38] It was made by an artist named Umar ibn Ali ibn al-Mubarak al-Mawsili ("from Mosul").[38] The manuscript is quite damaged, and miniatures often have been clumsily repainted.[38]

-

British Library, Ms. Or. 1200

-

British Library, Ms. Or. 1200

-

British Library, Ms. Or. 1200

-

Abū Zayd in the children's school. British Library, Ms. Or. 1200

Late 13th century edition (British Library, Ms. Or. 9718)

The manuscript is quite damaged, and many of the miniatures were repainted in rather recent times.[39] The original artist was from Damascus (folio 53r has a mention of the author "Work of Ghazi ibn 'Abd al-Rahman al-Dimashqi" who is known to have been born in 1232-3 and died in 1310 at the age of 80, and apparently lived in Damascus all his life).[39][40]

-

Two camel riders in Arab bedouin costumes. Maqamat, Syria, late 13th-century, British Library, Ms. Or. 9718.

-

Abū Zayd in the children's school. British Library, Ms. Or. 9718.

13th century edition (St Petersburg Ms. S.23)

This manuscript (also sometimes labelled Ms. C-23), although in rather poor condition, has many elaborate illustrations.[41] It is undated, and the place of origin is unknown.[25]

-

Abu Zayd before the governor of Merv (Maqāma 28). Saint-Petersburg Ms. S.23.

-

A ship bound for Oman (Maqāma 39). Saint Petersburg, Russian Academy of Sciences, Ms. S.23.

-

Assembly

-

Travelers

Early 14th century edition (British Library, Ms. Or. Add. 22114)

This manuscript may have been made in Syria, in the early 14th century.[42][39] The first and last pages were lost.[39] Many miniatures are well preserved, but they are dull and repetitive, suggesting a copy without much invention.[39] A governorial figure wearing typically Seljuq or Turkic costume, particularly the sharbush headgear, and quite similar to the figure of Badr ad-Din Lu'lu' in other manuscripts, appears in one of the folios.[43]

-

MS add 22114, folio 96r

-

MS add 22114, folio 94

-

British Library, Ms. Or. Add. 22114

-

British Library, Ms. Or. Add. 22114

1323 edition (British Library, Ms. Or. 7293)

This manuscript has a colophon describing the date of its manufacture as 1323.[44] It is beautifully made, and suggests a luxury edition.[44] Still, many of the miniatures are left blank and were never completed.[44] It may have been copied from the Paris 5847 edition.[44] The manuscript was acquired by a tax collector in Damascus in 1375-1376, according to an inscription on the first page.[44]

-

Maqamat, British Library, Ms. Or. Add. 7293

-

Maqamat, British Library, Ms. Or. Add. 7293 (detail). Abu Zayd and his audience (3rd maqama)

1334 edition (Vienna ÖNB AF9)

The 1334 edition is dated to the Egyptian Mamluk era, and was published in Egypt or Syria, most probably in Cairo.[45] It is now in Vienna, Austria (Vienna ÖNB AF9). The fronstispiece shows an enthroned Prince at his court. The style is Turkic: "In the paintings the facial cast of these [ruling] Turks is obviously reflected, and so are the special fashions and accoutrements they favored".[46] The ruler may be the Mamluk Sultan An-Nasir Muhammad.[47][48]

-

Frontispiece with Mamluk court scene. Probably Egypt, dated 1334. Maqamat of Al-Hariri.[49]

-

Maqamat of al-Hariri, Vienna manuscript AF 9, 1334 CE Folio 42v

-

Maqamat of Al-Hariri, 1334

-

Maqamat of Al-Hariri, 1334

1337 edition (Oxford Bodleian, Marsh 458)

Only a few pages of this manuscript remain.[45] The colophon indicates that it was manufactured in 1337 for an official at the Mamluk court, the Mamluk amir Nasir al-Din Muhammad, son of Husam al-Din Tarantay Silahdar, in Cairo, Egypt.[45][50]

-

Ms. Marsh 458, Frontispiece

-

Ms. Marsh 458, Folio 7b

-

Ms. Marsh 458, Folio 29b

-

Ms. Marsh 458, Folio 77b

Figures of the Qadi (judges or governors)

Figures of Qadis or Governors appears recurrently in the various editions of Maqamat al-Hariri, from the 13th century miniatures of North Jazira down to those of the Mamluk period.[43] These are characteristic of the figures of princely cycle and courtly life in early Islamic art. These figures are generally similar to Seljuq depictions of authority, wearing typically Seljuq or Turkic costumes, particularly the sharbush headgear, with distinctive facial features, and sitting cross-legged on a throne with one hand on the knee and one arm raised.[43] These figures are also similar to those in the frontispieces of the Kitab al-Aghani and Kitab al-Diryaq of the mid-13th century. In all manuscripts, these figures of power and authority in Seljuk style are very different from the otherwise omnipresent figures in Arabic style with their long robes and turbans.[43][2]

List of stories

After a preface by al-Hariri himself, there are 50 stories altogether, generally entitled on the format "Encounter at....", with the name of a different city for each story. The cities are in order:[51]

1-10 "Encounter at San'a", Holwan, Kayla, Damietta, Kufa, Maraghah (or "The Diversified"), Barkaid, Ma'arrah, Alexandria, Rabah

11-20 "Encounter at Saweh", Damascus, Baghdad, Mecca, "Encounter called "The Legal"", "Encounter of the West", "Encounter called "The Reversed"", Sinjar, Nasibin, Mayyafariqin

21-30 "Encounter at Rayy al-Mahdiyeh", Euphrates, "Encounter of the Precinct", "Encounter called "Of the Portion"", Kerej, "The Encounter of the address", "The Encounter of the Tent-dwellers", Samarkand, Wasit, Sur

31-40 "Encounter at Ramlah", Tayleh, Tiflis, Zabid, Shiraz, Maltiyah, Sa'dah, Merv, Oman, Tabriz

41-50 "Encounter at Tanis", Najran, Al-Bakriya, "The Encounter called "The Wintry"", Ramlah, Aleppo, Hajr, Harmamiyeh, Sasan, Basra.[51]

See also

Notes

- ^ Hillenbrand 2010, p. 118.

- ^ a b c d e f Flood, Finbarr Barry (2017). "A Turk in the Dukhang? Comparative Perspectives on Elite Dress in Medieval Ladakh and the Caucasus". Interaction in the Himalayas and Central Asia. Austrian Academy of Science Press: 232.

- ^ Hillenbrand 2010, p. 119.

- ^ Grabar 1984, p. 7.

- ^ Grabar 1984, p. 17.

- ^ George, Alain (February 2012). "Orality, Writing and the Image in the Maqamat : Arabic Illustrated Books in Context". Art History. 35 (1): 10–37. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8365.2011.00881.x.

- ^ MacKay, Pierre A. (1971). "Certificates of Transmission on a Manuscript of the Maqāmāt of Ḥarīrī (MS. Cairo, Adab 105)". Transactions of the American Philosophical Society. 61 (4). doi:10.2307/1006055. ISSN 0065-9746.

- ^ MacKay, Pierre A. (1971). "Certificates of Transmission on a Manuscript of the Maqāmāt of Ḥarīrī (MS. Cairo, Adab 105)". Transactions of the American Philosophical Society. 61 (4): 6. doi:10.2307/1006055. ISSN 0065-9746.

- ^ George, Alain (February 2012). "Orality, Writing and the Image in the Maqamat : Arabic Illustrated Books in Context". Art History. 35 (1): 10–37. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8365.2011.00881.x.

Originality and realism were clearly not among the aims of their author, which has led some modern scholars to rate his work as inferior to that of the founder of the genre, al-Hamadhani (968–1008 CE). Yet this perception was not shared by Arabic-speaking audiences of the twelfth century onwards, amongst whom al-Hariri's Maqamat almost immediately became a classic, soon eclipsing earlier writings of the same genre and spawning emulations in Hebrew, Syriac and Persian. So considerable was their popularity that, according to an anecdote cited by Yaqut al-Rumi (c. 1179–1229), al-Hariri had authorized seven hundred copies of the text in his lifetime.

- ^ George, Alain (February 2012). "Orality, Writing and the Image in the Maqamat : Arabic Illustrated Books in Context". Art History. 35 (1): 10–37. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8365.2011.00881.x.

The Islamic world witnessed, in the twelfth to thirteenth centuries, an explosion of figural art. (...) The making of it is forbidden under every circumstance, because it implies a likeness to the creative activity of God

- ^ "Consultation Arabe 3929". archivesetmanuscrits.bnf.fr.

- ^ Contadini 2012, p. 120, fig. 45.

- ^ Balafrej, Lamia (19 December 2022). "Automated Slaves, Ambivalent Images, and Noneffective Machines in al-Jazari's Compendium of the Mechanical Arts, 1206". Inquiries into Art. History: 766, Fig.11. doi:10.11588/xxi.2022.4.91685.

- ^ Balafrej, Lamia (19 December 2022). "Automated Slaves, Ambivalent Images, and Noneffective Machines in al-Jazari's Compendium of the Mechanical Arts, 1206". Inquiries into Art. History: 739–741. doi:10.11588/xxi.2022.4.91685.

- ^ Ward, Rachel (1 January 1985). "Evidence for a School of Painting at the Artuqid Court". Oxfod Studies in Islamic Art, vol. 1, pp. 69-83: 76–77.

- ^ Sakkal, Aya (25 August 2014). "La représentation du héros des Maqāmāt d'al-Ḥarīrī dans les trois premiers manuscrits illustrés". Annales islamologiques (in French) (48.1): 79–102. doi:10.4000/anisl.3080. ISSN 0570-1716.

Most of the illustrations are simple and at first glance quite literal, and for this reason most scholars have assigned the manuscript to the early thirteenth century, or even to the late twelfth. A more sophisticated discussion by Rice of one group of illustrations led him to a date sometime in the 1240. (Grabar, The Illustrations of the Maqamat, p. 8.)

- ^ Grabar 1984, p. 8.

- ^ Balafrej, Lamia (19 December 2022). "Automated Slaves, Ambivalent Images, and Noneffective Machines in al-Jazari's Compendium of the Mechanical Arts, 1206". Inquiries into Art. History: 768. doi:10.11588/xxi.2022.4.91685.

- ^ "Makamat de Hariri 6094". 1222.

- ^ Sakkal, Aya (25 August 2014). "La représentation du héros des Maqāmāt d'al-Ḥarīrī dans les trois premiers manuscrits illustrés". Annales islamologiques (in French) (48.1): 79–102. doi:10.4000/anisl.3080. ISSN 0570-1716.

- ^ a b Grabar 1984, p. 9.

- ^ Keresztély, Kata (14 December 2018). Fiction Painting : a Medieval Arabic Tradition. p. 351.

- ^ Stillman, Norman (8 June 2022). Arab Dress, A Short History: From the Dawn of Islam to Modern Times. BRILL. p. 68, note 12. ISBN 978-90-04-49162-5.

- ^ Hillenbrand 2010, p. 117.

- ^ a b c Grabar 1984, p. 10.

- ^ a b Contadini 2012, p. 155.

- ^ "BNF Arabe 5847". archivesetmanuscrits.bnf.fr. Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

- ^ a b Hillenbrand 2010.

- ^ a b Ettinghausen 1977, p. 104. sfn error: multiple targets (3×): CITEREFEttinghausen1977 (help)

- ^ Grabar.

- ^ "Al Maqamat: Beautifully Illustrated Arabic Literary Tradition – 1001 Inventions". Retrieved 2023-07-28.

- ^ a b Hillenbrand 2010, p. 126 and note 40.

- ^ a b c Contadini 2012, p. 126–127: "Official" Turkish figures wear a standard combination of a sharbūsh, a three-quarters length robe, and boots. Arab figures, in contrast, have different headgear (usually a turban), a robe that is either full-length or, if three-quarters length, has baggy trousers below, and they usually wear flat shoes or (...) go barefoot (...) P.127: Reference has already been made to the combination of boots and sharbūsh as markers of official status (...) the combination is standard, even being reflected in thirteenth-century Coptic paintings, and serves to distinguish, in Grabar's formulation, the world of the Turkish ruler and that of the Arab. (...) The type worn by the official figures in the 1237 Maqāmāt, depicted, for example, on fol. 59r,67 consists of a gold cap surmounted by a little round top and with fur trimming creating a triangular area at the front which either shows the gold cap or is a separate plaque. A particular imposing example in this manuscript is the massive sharbūsh with much more fur than usual that is worn by the princely official on the right frontispiece on fol. 1v."

- ^ Shah 1980, pp. 193–198, Maqāma 39, "The encounter at Oman".

- ^ Contadini 2012, p. 143.

- ^ Hillenbrand 2010, p. 118, note 10.

- ^ Shah 1980, pp. 84–88, Maqāma 21, "The encounter at Rayy al-Mahdiyeh".

- ^ a b c d e Grabar 1984, p. 12.

- ^ a b c d e Grabar 1984, p. 13.

- ^ McSweeney, Anna. "The Maqamat of al-Hariri. Two Illustrated Mamluk Manuscripts at the British Library MS Or.9718 and Ms.Add.22114.pdf (MA Thesis, SOAS)". SOAS Dept. Art and Archaeology: 4.

- ^ Grabar 1984, p. 11.

- ^ Fontana, M.V. (1 January 2020). Islam and the West. Arabic inscriptions and pseudo inscriptions. Mantova: Universitas Studiorum. ISBN 9788833690735. Universitas Studiorum Publishing. p. 126, note 34.

- ^ a b c d McSweeney, Anna. "The Maqamat of al-Hariri. Two Illustrated Mamluk Manuscripts at the British Library MS Or.9718 and Ms.Add.22114.pdf (MA Thesis, SOAS)". SOAS Dept. Art and Archaeology: 29–30.

- ^ a b c d e Grabar 1984, p. 14.

- ^ a b c Grabar 1984, p. 15.

- ^ Ettinghausen, Richard (1977). Arab painting. New York : Rizzoli. p. 162. ISBN 978-0-8478-0081-0.

- ^ "Al-Hariri, Maqamat ('Assemblies') - Discover Islamic Art - Virtual Museum". islamicart.museumwnf.org.

The sultan who possibly commissioned the manuscript and who may be the one depicted on the dedicatory title page is An-Nasir Muhammad b. Qala'un, who was in power for the third time from 709 AH / 1309-10 AD to 741 AH / 1340-41 AD.

- ^ Yedida Kalfon Stillman, Norman A. Stillman (2003). Arab Dress: A Short History : from the Dawn of Islam to Modern Times. Leiden, Netherlands: Brill. pp. Fig.22. ISBN 9789004113732.

Fig. 22. Frontispiece of a court scene from a Maqamat manuscript, probably from Egypt, dated 1334. The enthroned prince wears a brocaded qabli' maftulJ with inscribed Tiraz armbands over a qabli' turki which is clinched at the waist with a hiyasa of gold roundels (bawlikir). The two musicians at the lower right both wear turkic coats and plumed caps, one of which has an upwardly turned brim. The plumes are set in a front metal plaque ('amud) (Nationalbibliothek, Vienna, ms A. F. 9, fol. 1).

- ^ Ettinghausen, Richard (1977). Arab painting. New York : Rizzoli. p. 148. ISBN 978-0-8478-0081-0.

- ^ George, Alain (February 2012). "Orality, Writing and the Image in the Maqamat : Arabic Illustrated Books in Context". Art History. 35 (1): 10–37. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8365.2011.00881.x.

Only one illustrated copy of the Maqamat (Oxford Marsh 458) was dedicated to a named individual, the Mamluk amir Nasir al-Din Muhammad, son of Husam al-Din Tarantay Silahdar, for whom it was completed in 1337.

- ^ a b Shah 1980.

Sources

- Contadini, Anna (1 January 2012). A World of Beasts: A Thirteenth-Century Illustrated Arabic Book on Animals (the Kitāb Na't al-Ḥayawān) in the Ibn Bakhtīshū' Tradition. Brill. doi:10.1163/9789004222656_005.

- Ettinghausen, Richard (1977). La Peinture arabe (in French). Geneva: Skira. pp. 104–124.

- Grabar, Oleg (1984). The Illustrations of the Maqamat (PDF). University of Chicago Press. p. 7.

- Grabar, Oleg. "Maqamat Al-Hariri: Illustrated Arabic Manuscript from the 13th century". Retrieved 24 January 2023.

- Hillenbrand, Robert (1 January 2010). "The Schefer Ḥarīrī: A Study in Islamic Frontispiece Design". Arab Painting: 117–134. doi:10.1163/9789004236615_011.

- Shah, Amina (1980). The assemblies of al-Hariri : fifty encounters with the Shaykh Abu Zayd of Seruj. London : Octagon Press. ISBN 978-0-900860-86-7.

External links

Media related to Maqamat of al-Hariri at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Maqamat of al-Hariri at Wikimedia Commons- Les Makamat de Hariri; exemplaire orné de peintures exécutées par Yahya ibn Mahmoud ibn Yahya ibn Aboul-Hasan ibn Kouvarriha al-Wasiti., online digitisation of the BnF manuscript

![A Jariya prostitute.[18]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/9d/Arabe_3929%2C_151%2C_Jariya.jpg/137px-Arabe_3929%2C_151%2C_Jariya.jpg)

![Maqamat 1222, 133v, Turkic ruler detail, wearing sharbūsh.[22]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/43/Maqamat_6094%2C_folio_133v_%28ruler%29.jpg/147px-Maqamat_6094%2C_folio_133v_%28ruler%29.jpg)

![Maqamat 1222, 167r. Students, some wearing the Arab turban, others Turkic caps.[23]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/e9/Maqamat_6094%2C_folio_167r_%28students_detail%29.jpg/200px-Maqamat_6094%2C_folio_167r_%28students_detail%29.jpg)

![Left frontispiece (1v): ruler in Turkic dress (long braids, Sharbush fur hat, boots, fitting coat), in the Maqamat of al-Hariri, 1237 CE, possibly Baghdad.[2][32][33]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4b/Ruler_in_Turkic_dress_%28long_braids%2C_fur_hat%2C_boots%2C_fitting_coat%29%2C_in_the_Maqamat_of_al-Hariri%2C_1237_CE%2C_probably_Baghdad.jpg/125px-Ruler_in_Turkic_dress_%28long_braids%2C_fur_hat%2C_boots%2C_fitting_coat%29%2C_in_the_Maqamat_of_al-Hariri%2C_1237_CE%2C_probably_Baghdad.jpg)

![Right frontispiece (2r): possible depiction of the author al-Hariri himself, in the Maqamat of al-Hariri, 1237 CE, possibly Baghdad.[2][28]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/e6/Possible_depiction_of_al-Hariri%2C_in_the_Maqamat_of_al-Hariri%2C_1237_CE%2C_probably_Baghdad.jpg/127px-Possible_depiction_of_al-Hariri%2C_in_the_Maqamat_of_al-Hariri%2C_1237_CE%2C_probably_Baghdad.jpg)

![A ship bound for Oman (Maqāma 39).[34]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d9/Maqamat_5847%2C_f.119v-_maqama_39_Abu_Zayd_and_al-Harith_sailing.jpg/170px-Maqamat_5847%2C_f.119v-_maqama_39_Abu_Zayd_and_al-Harith_sailing.jpg)

![Ayyubid Governor of Rahba, with Abū Zayd and his son.[35]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/6d/Yahy%C3%A2_ibn_Mahm%C3%BBd_al-W%C3%A2sit%C3%AE_001.jpg/200px-Yahy%C3%A2_ibn_Mahm%C3%BBd_al-W%C3%A2sit%C3%AE_001.jpg)

![Turkic amir with guards, wearing the Turkic headgear Sharbush, in the preaching scene at Rayy, Iran,[36][33] , in maqāma 21 (fols. 58v–59r).[37]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/2b/Turkic_guard_in_Preaching_scene_at_Rayy_in_maq%C4%81ma_21_%28fols._58v%E2%80%9359r%2C_douvle-page_spread_as_a_unit%29%2C_Maqamat_al-Harari_1237.jpg/200px-Turkic_guard_in_Preaching_scene_at_Rayy_in_maq%C4%81ma_21_%28fols._58v%E2%80%9359r%2C_douvle-page_spread_as_a_unit%29%2C_Maqamat_al-Harari_1237.jpg)

![Frontispiece with Mamluk court scene. Probably Egypt, dated 1334. Maqamat of Al-Hariri.[49]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/12/Maqamat_of_al-Hariri._Enthroned_Prince._Probably_Egypt_1334.jpg/160px-Maqamat_of_al-Hariri._Enthroned_Prince._Probably_Egypt_1334.jpg)