69.118.69.171 (talk) aceeeeeeeeeeee white chocolate |

Eric Kvaalen (talk | contribs) Apparently Li is 33rd most common in cosmos, not on Earth. Added quotes on Li being comparatively rare and not suitable for electric vehicles on a large scale. |

||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

'''Lithium''' ({{pronEng|ˈlɪθiəm}}) is a [[chemical element]] with the symbol '''Li''' and [[atomic number]] 3. It is a soft [[alkali metal]] with a silver-white color. Under [[standard conditions for temperature and pressure gfgf|standard conditions]], it is the lightest [[metal]] and the least dense [[solid]] element. Like all alkali metals, lithium is highly reactive, [[corrosion|corroding]] quickly in moist [[air]] to form a black tarnish. For this reason, lithium metal is typically stored under the cover of [[oil]]. When cut open, lithium exhibits a metallic [[lustre (mineralogy)|lustre]], but contact with oxygen quickly returns it back to a dull silvery grey color. Lithium is also highly flammable. |

'''Lithium''' ({{pronEng|ˈlɪθiəm}}) is a [[chemical element]] with the symbol '''Li''' and [[atomic number]] 3. It is a soft [[alkali metal]] with a silver-white color. Under [[standard conditions for temperature and pressure gfgf|standard conditions]], it is the lightest [[metal]] and the least dense [[solid]] element. Like all alkali metals, lithium is highly reactive, [[corrosion|corroding]] quickly in moist [[air]] to form a black tarnish. For this reason, lithium metal is typically stored under the cover of [[oil]]. When cut open, lithium exhibits a metallic [[lustre (mineralogy)|lustre]], but contact with oxygen quickly returns it back to a dull silvery grey color. Lithium is also highly flammable. |

||

According to theory, lithium (mostly <sup>7</sup>Li) was one of the few elements [[Big Bang nucleosynthesis|synthesized]] in the [[Big Bang]], although its quantity has vastly decreased. The reasons for its disappearance and the processes by which new lithium is created continue to be important matters of study in [[astronomy]]. Lithium is |

According to theory, lithium (mostly <sup>7</sup>Li) was one of the few elements [[Big Bang nucleosynthesis|synthesized]] in the [[Big Bang]], although its quantity has vastly decreased. The reasons for its disappearance and the processes by which new lithium is created continue to be important matters of study in [[astronomy]]. Lithium is tied with [[Krypton]] as 32nd or 33rd most abundant element in the [[cosmos]] (see [[Cosmochemical Periodic Table of the Elements in the Solar System]]), being |

||

less common than any element before Rb (element 37) except for Sc, Ga, As, and Br, yet more common than any element beyond Kr (element 36). |

|||

Due to its high [[reactivity]] it only appears naturally on Earth in the form of [[chemical compound|compounds]]. Lithium occurs in a number of [[pegmatite|pegmatitic]] [[mineral]]s, but is also commonly obtained from [[brine]]s and [[clay]]s; on a commercial scale, lithium metal is isolated [[electrolysis|electrolytically]] from a mixture of [[lithium chloride]] and [[potassium chloride]]. |

|||

Trace amounts of lithium are present in the [[ocean]]s and in some organisms, though the element serves no apparent biological function in humans. Nevertheless, the neurological effect of the lithium ion Li<sup>+</sup> makes some lithium [[salt (chemistry)|salt]]s useful as a class of [[mood stabilizer|mood stabilizing]] drugs. Lithium and its compounds have several other commercial applications, including heat-resistant [[glass]] and [[ceramic]]s, high strength-to-weight [[alloy]]s used in [[aircraft]], and [[lithium battery|lithium batteries]]. Lithium also has important links to [[nuclear physics]]: the [[nuclear fission|splitting]] of lithium atoms was the first man-made form of a [[nuclear reaction]], and [[lithium deuteride]] serves as the [[nuclear fusion|fusion]] fuel in [[Teller-Ulam design|staged thermonuclear weapon]]s. |

Trace amounts of lithium are present in the [[ocean]]s and in some organisms, though the element serves no apparent biological function in humans. Nevertheless, the neurological effect of the lithium ion Li<sup>+</sup> makes some lithium [[salt (chemistry)|salt]]s useful as a class of [[mood stabilizer|mood stabilizing]] drugs. Lithium and its compounds have several other commercial applications, including heat-resistant [[glass]] and [[ceramic]]s, high strength-to-weight [[alloy]]s used in [[aircraft]], and [[lithium battery|lithium batteries]]. Lithium also has important links to [[nuclear physics]]: the [[nuclear fission|splitting]] of lithium atoms was the first man-made form of a [[nuclear reaction]], and [[lithium deuteride]] serves as the [[nuclear fusion|fusion]] fuel in [[Teller-Ulam design|staged thermonuclear weapon]]s. |

||

== History and etymology== |

|||

ace takes that shit! |

|||

[[Petalite]] (lithium aluminium silicate) was first described in 1800 by the [[Brazil]]ian ([[Brazilian Declaration of Independence|then]] [[Portugal|Portuguese]]) scientist [[José Bonifácio de Andrade e Silva]], who discovered the mineral in a [[Sweden|Swedish]] [[iron mine]] on the island of [[Utö, Sweden|Utö]]. However, it was not until 1817 that [[Johan August Arfwedson]], then a trainee in the laboratory of [[Jöns Jakob Berzelius]], [[discovery of the chemical elements|discovered]] the presence of a new element while analyzing petalite ore. The element formed compounds similar to those of [[sodium]] and [[potassium]], though its [[carbonate]] and [[hydroxide]] were less [[solubility|water soluble]] and had a larger capacity to neutralize acid. Berzelius gave the alkaline material the name "lithos", from the [[Greek language|Greek]] ''λιθoς'' (''lithos'', "stone"), to reflect its discovery in a mineral, as opposed to sodium and potassium which had been discovered in [[plant]] tissue; its name would later be standardized as "lithium". Arfwedson later showed that this same element was present in the mineral ores [[spodumene]] and [[lepidolite]]. In 1818, [[Christian Gmelin]] was the first to observe that lithium salts give a bright red color in flame. However, both Arfwedson and Gmelin tried and failed to isolate the element from its salts.<ref name=we-hist>{{cite web |last= Winter |first= Mark J|url=http://www.webelements.com/webelements/elements/text/Li/hist.html |title=Chemistry : Periodic Table: lithium: historical information | accessdate = 2007-08-19| publisher=Web Elements}}</ref><ref name=eote>{{cite book | year = 2004 | title = Encyclopedia of the Elements: Technical Data - History - Processing - Applications | publisher = Wiley | isbn = 978-3527306664 | pages = 287–300}}</ref><ref>{{cite web | publisher = Elementymology & Elements Multidict | title = Lithium| first = Peter | last =van der Krogt | url = http://www.vanderkrogt.net/elements/elem/li.html| accessdate = 2008-09-18}}</ref> The element was not isolated until 1821, when [[William Thomas Brande]] performed [[electrolysis]] on [[lithium oxide]], a process which had previously been employed by [[Sir Humphry Davy]] to isolate potassium and sodium.<ref name=eote/><ref>{{cite web | url = http://www.diracdelta.co.uk/science/source/t/i/timeline/source.html | title = Timeline science and engineering | publisher = DiracDelta Science & Engineering Encyclopedia| accessdate = 2008-09-18}}</ref> Brande also described pure salts of lithium, such as the chloride, and performed an estimate of its atomic weight. In 1855, [[Robert Bunsen]] and Augustus Matthiessen produced large quantities of the metal by electrolysis of [[lithium chloride]]. Commercial production of lithium metal began in 1923 by the German company [[Metallgesellschaft AG]] through the electrolysis of a molten mixture of lithium chloride and [[potassium chloride]].<ref name=we-hist/><ref>{{cite web| url = http://www.echeat.com/essay.php?t=29195 | title = Analysis of the Element Lithium |

|||

| first = Thomas | last = Green | date 2006-06-11| publisher = echeat}}</ref> |

|||

== Properties == |

== Properties == |

||

| Line 38: | Line 42: | ||

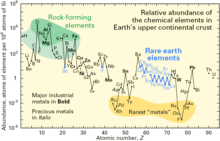

[[Image:Relative abundance of elements.png|thumb|right|Lithium is about as common as [[chlorine]] in the earth's upper continental [[Crust (geology)|crust]], on a per-atom basis.]] |

[[Image:Relative abundance of elements.png|thumb|right|Lithium is about as common as [[chlorine]] in the earth's upper continental [[Crust (geology)|crust]], on a per-atom basis.]] |

||

{{see also|:category:Lithium minerals|l1=Lithium minerals}} |

{{see also|:category:Lithium minerals|l1=Lithium minerals}} |

||

Lithium is widely distributed on Earth, |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

<ref name=krebs>{{cite book | last = Krebs | first = Robert E. | year = 2006 | title = The History and Use of Our Earth's Chemical Elements: A Reference Guide | publisher = Greenwood Press | location = Westport, Conn. | isbn = 0-313-33438-2 | pages = 47–50}} |

|||

| ⚫ | </ref> however, it does not naturally occur in elemental form due to its high reactivity. Estimates for [[crust (geology)|crustal]] content range from 20 to 70 ppm by weight.<ref name=kamienski/> In keeping with its name, lithium forms a minor part of [[igneous]] rocks, with the largest concentrations in [[granite]]s. Granitic [[pegmatite]]s also provide the greatest abundance of lithium-containing minerals, with [[spodumene]] and [[petalite]] being the most commercially-viable mineral sources for the element.<ref name=kamienski/> |

||

According to the ''Handbook of Lithium and Natural Calcium'', "Lithium is a comparatively rare element, although it is found in many rocks and some brines, but always in very low concentrations. There are a fairly large number of both lithium mineral and brine deposits but only comparatively a few of them are of actual or potential commercial value. Many are very small, others are too low in grade."<ref>''Handbook of Lithium and Natural Calcium'', [[Donald Garrett]], [[Academic Press]], 2004, cited in ''[http://www.meridian-int-res.com/Projects/Lithium_Microscope.pdf The Trouble with Lithium 2]''</ref> |

|||

== Applications == |

== Applications == |

||

| Line 81: | Line 90: | ||

== Production == |

== Production == |

||

Since the end of [[World War II]], lithium metal production has greatly increased. |

Since the end of [[World War II]], lithium metal production has greatly increased. The metal is separated from other elements in igneous mineral such as those above, and is also extracted from the water of [[mineral springs]]. |

||

There are wide-spread hopes of using [[lithium ion batteries]] in [[electric vehicles]], but one study concluded that "realistically achievable lithium carbonate production will be sufficient for only a small fraction of future [[PHEV]] and [[electric vehicle|EV]] global market requirements", that "demand from the portable electronics sector will absorb much of the planned production increases in the next decade", and that "mass productioin of lithium carbonate is not environmentally sound, it will cause irreparable ecological damage to ecosystems that should be protected and that [[LiIon]] propulsion is incompatible with the notion of the 'Green Car'".<ref name=Legers/> |

|||

The metal is produced [[electrolysis|electrolytically]] from a mixture of fused lithium and [[potassium chloride]]. In 1998 it was about [[US dollar|US$]] 43 per [[Pound (mass)|pound]] ($95 per [[kilogram|kg]]).<ref name=ober>{{cite web |url=http://minerals.usgs.gov/minerals/pubs/commodity/lithium/450798.pdf |title=Lithium | accessdate = 2007-08-19|last=Ober |first=Joyce A |format=pdf |pages = 77-78| publisher=[[United States Geological Survey]]}}</ref> |

The metal is produced [[electrolysis|electrolytically]] from a mixture of fused lithium and [[potassium chloride]]. In 1998 it was about [[US dollar|US$]] 43 per [[Pound (mass)|pound]] ($95 per [[kilogram|kg]]).<ref name=ober>{{cite web |url=http://minerals.usgs.gov/minerals/pubs/commodity/lithium/450798.pdf |title=Lithium | accessdate = 2007-08-19|last=Ober |first=Joyce A |format=pdf |pages = 77-78| publisher=[[United States Geological Survey]]}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 08:56, 9 October 2008

Lithium floating in oil | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Lithium | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˈlɪθiəm/ | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Appearance | silvery-white | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Standard atomic weight Ar°(Li) | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Lithium in the periodic table | |||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic number (Z) | 3 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Group | group 1: hydrogen and alkali metals | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Period | period 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Block | s-block | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Electron configuration | [He] 2s1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrons per shell | 2, 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Physical properties | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Phase at STP | solid | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Melting point | 453.65 K (180.50 °C, 356.90 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Boiling point | 1603 K (1330 °C, 2426 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Density (at 20° C) | 0.5334 g/cm3[3] | ||||||||||||||||||||

| when liquid (at m.p.) | 0.512 g/cm3 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Critical point | 3220 K, 67 MPa (extrapolated) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of fusion | 3.00 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of vaporization | 136 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar heat capacity | 24.860 J/(mol·K) | ||||||||||||||||||||

Vapor pressure

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic properties | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Oxidation states | 0[4], +1 (a strongly basic oxide) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Electronegativity | Pauling scale: 0.98 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Ionization energies |

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic radius | empirical: 152 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Covalent radius | 128±7 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Van der Waals radius | 182 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Other properties | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Natural occurrence | primordial | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Crystal structure | body-centered cubic (bcc) (cI2) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Lattice constant | a = 350.93 pm (at 20 °C)[3] | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal expansion | 46.56×10−6/K (at 20 °C)[3] | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal conductivity | 84.8 W/(m⋅K) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrical resistivity | 92.8 nΩ⋅m (at 20 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Magnetic ordering | paramagnetic | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar magnetic susceptibility | +14.2×10−6 cm3/mol (298 K)[5] | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Young's modulus | 4.9 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Shear modulus | 4.2 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Bulk modulus | 11 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Speed of sound thin rod | 6000 m/s (at 20 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Mohs hardness | 0.6 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Brinell hardness | 5 MPa | ||||||||||||||||||||

| CAS Number | 7439-93-2 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Discovery | Johan August Arfwedson (1817) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| First isolation | William Thomas Brande (1821) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Isotopes of lithium | |||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

Lithium (Template:PronEng) is a chemical element with the symbol Li and atomic number 3. It is a soft alkali metal with a silver-white color. Under standard conditions, it is the lightest metal and the least dense solid element. Like all alkali metals, lithium is highly reactive, corroding quickly in moist air to form a black tarnish. For this reason, lithium metal is typically stored under the cover of oil. When cut open, lithium exhibits a metallic lustre, but contact with oxygen quickly returns it back to a dull silvery grey color. Lithium is also highly flammable.

According to theory, lithium (mostly 7Li) was one of the few elements synthesized in the Big Bang, although its quantity has vastly decreased. The reasons for its disappearance and the processes by which new lithium is created continue to be important matters of study in astronomy. Lithium is tied with Krypton as 32nd or 33rd most abundant element in the cosmos (see Cosmochemical Periodic Table of the Elements in the Solar System), being less common than any element before Rb (element 37) except for Sc, Ga, As, and Br, yet more common than any element beyond Kr (element 36). Due to its high reactivity it only appears naturally on Earth in the form of compounds. Lithium occurs in a number of pegmatitic minerals, but is also commonly obtained from brines and clays; on a commercial scale, lithium metal is isolated electrolytically from a mixture of lithium chloride and potassium chloride.

Trace amounts of lithium are present in the oceans and in some organisms, though the element serves no apparent biological function in humans. Nevertheless, the neurological effect of the lithium ion Li+ makes some lithium salts useful as a class of mood stabilizing drugs. Lithium and its compounds have several other commercial applications, including heat-resistant glass and ceramics, high strength-to-weight alloys used in aircraft, and lithium batteries. Lithium also has important links to nuclear physics: the splitting of lithium atoms was the first man-made form of a nuclear reaction, and lithium deuteride serves as the fusion fuel in staged thermonuclear weapons.

History and etymology

Petalite (lithium aluminium silicate) was first described in 1800 by the Brazilian (then Portuguese) scientist José Bonifácio de Andrade e Silva, who discovered the mineral in a Swedish iron mine on the island of Utö. However, it was not until 1817 that Johan August Arfwedson, then a trainee in the laboratory of Jöns Jakob Berzelius, discovered the presence of a new element while analyzing petalite ore. The element formed compounds similar to those of sodium and potassium, though its carbonate and hydroxide were less water soluble and had a larger capacity to neutralize acid. Berzelius gave the alkaline material the name "lithos", from the Greek λιθoς (lithos, "stone"), to reflect its discovery in a mineral, as opposed to sodium and potassium which had been discovered in plant tissue; its name would later be standardized as "lithium". Arfwedson later showed that this same element was present in the mineral ores spodumene and lepidolite. In 1818, Christian Gmelin was the first to observe that lithium salts give a bright red color in flame. However, both Arfwedson and Gmelin tried and failed to isolate the element from its salts.[7][8][9] The element was not isolated until 1821, when William Thomas Brande performed electrolysis on lithium oxide, a process which had previously been employed by Sir Humphry Davy to isolate potassium and sodium.[8][10] Brande also described pure salts of lithium, such as the chloride, and performed an estimate of its atomic weight. In 1855, Robert Bunsen and Augustus Matthiessen produced large quantities of the metal by electrolysis of lithium chloride. Commercial production of lithium metal began in 1923 by the German company Metallgesellschaft AG through the electrolysis of a molten mixture of lithium chloride and potassium chloride.[7][11]

Properties

Like other alkali metals, lithium has a single valence electron which it will readily lose to form a cation, indicated by the element's low electronegativity. As a result, lithium is easily deformed, highly reactive, and has lower melting and boiling points than most metals. These and many other properties attributable to alkali metals' weakly held valence electron are most distinguished in lithium, as it possesses the smallest atomic radius and thus the highest electronegativity of the alkali group.

In addition, lithium has a diagonal relationship with magnesium, an element of similar atomic and ionic radius. Chemical resemblances between the two metals include the formation of a nitride by reaction with N2, the formation of an oxide when burnt in O2, salts with similar solubilities, and thermal instability of the carbonates and nitrides.[12]

Lithium is soft enough to be cut with a knife, though this is more difficult than cutting sodium. The fresh metal has a silvery-white color which only remains untarnished in dry air.[12] Lithium has about half the density of water, giving solid sticks of lithium metal the odd heft of a light-to-medium wood such as pine. The metal floats highly in hydrocarbons; in the laboratory, jars of lithium are typically composed of black-coated sticks held down in hydrocarbon mechanically by the jar's lid and other sticks.

Lithium is greatly heat-resistant, possessing a low coefficient of thermal expansion and the highest specific heat capacity of any solid element. Lithium has also been found to be superconductive below 400 μK. This finding paves the way for further study of superconductivity, as lithium's atomic lattice is the simplest of all metals.

Chemistry

In moist air, lithium metal rapidly tarnishes to form a black coating of lithium hydroxide (LiOH and LiOH·H2O), lithium nitride (Li3N) and lithium carbonate (Li2CO3, the result of a secondary reaction between LiOH and CO2).[12]

When placed over a flame, lithium gives off a striking crimson color, but when it burns strongly, the flame becomes a brilliant white. Lithium will ignite and burn in oxygen when exposed to water or water vapours. It is the only metal that reacts with nitrogen at room temperature.

Lithium metal is flammable and potentially explosive when exposed to air and especially water, though it is far less dangerous than other alkali metals in this regard. The lithium-water reaction at normal temperatures is brisk but not violent. Lithium fires are difficult to extinguish, requiring special chemicals designed to smother them (see sodium for details).

Isotopes

Naturally occurring lithium is composed of two stable isotopes 6Li and 7Li, the latter being the more abundant (92.5% natural abundance).[13] Seven radioisotopes have been characterized, the most stable being 8Li with a half-life of 838 ms and 9Li with a half-life of 178.3 ms. All of the remaining radioactive isotopes have half-lives that are shorter than 8.6 ms. The shortest-lived isotope of lithium is 4Li which decays through proton emission and has a half-life of 7.58043x10-23 s.

7Li is one of the primordial elements or, more properly, primordial isotopes, produced in Big Bang nucleosynthesis (a small amount of 6Li is also produced in stars).[14] Lithium isotopes fractionate substantially during a wide variety of natural processes, including mineral formation (chemical precipitation), metabolism, and ion exchange. Lithium ion substitutes for magnesium and iron in octahedral sites in clay minerals, where 6Li is preferred to 7Li, resulting in enrichment of the light isotope in processes of hyperfiltration and rock alteration. The exotic 11Li is known to exhibit a nuclear halo.

Natural occurrence

Lithium is widely distributed on Earth, [15] however, it does not naturally occur in elemental form due to its high reactivity. Estimates for crustal content range from 20 to 70 ppm by weight.[12] In keeping with its name, lithium forms a minor part of igneous rocks, with the largest concentrations in granites. Granitic pegmatites also provide the greatest abundance of lithium-containing minerals, with spodumene and petalite being the most commercially-viable mineral sources for the element.[12]

According to the Handbook of Lithium and Natural Calcium, "Lithium is a comparatively rare element, although it is found in many rocks and some brines, but always in very low concentrations. There are a fairly large number of both lithium mineral and brine deposits but only comparatively a few of them are of actual or potential commercial value. Many are very small, others are too low in grade."[16]

Applications

Because of its specific heat capacity, the highest of all solids, lithium is often used in heat transfer applications.

It is an important ingredient in anode materials, used in rechargeable and primary batteries because of its high electrochemical potential, light weight, and high current density.

Large quantities of lithium are also used in the manufacture of organolithium reagents, especially n-butyllithium which has many uses in fine chemical and polymer synthesis.

Medical use

Lithium salts were used during the 19th century to treat gout. Lithium salts such as lithium carbonate (Li2CO3), lithium citrate, and lithium orotate are mood stabilizers. They are used in the treatment of bipolar disorder, since unlike most other mood altering drugs, they counteract both mania and depression. Lithium can also be used to augment other antidepressant drugs. It is also sometimes prescribed as a preventive treatment for migraine disease and cluster headaches.[citation needed]

The active principle in these salts is the lithium ion Li+, which having a smaller diameter, can easily displace K+ and Na+ and even Ca2+, in spite of its greater charge, occupying their sites in several critical neuronal enzymes and neurotransmitter receptors. Although Li+ cannot displace Mg2+ and Zn2+, because of these ions' small size and greater charge (higher charge density, hence stronger bonding), when Mg2+ or Zn2+ are present in low concentrations, and Li+ is present in high concentrations, the latter can occupy sites normally occupied by Mg2+ or Zn2+ in various enzymes. Therapeutically useful amounts of lithium (~ 0.6 to 1.2 mmol/l) are only slightly lower than toxic amounts (>1.5 mmol/l), so the blood levels of lithium must be carefully monitored during treatment to avoid toxicity.

Common side effects of lithium treatment include muscle tremors, twitching, ataxia, hyperparathyroidism, bone loss, hypercalcemia, hypertension, etc.), kidney damage, nephrogenic diabetes insipidus (polyuria and polydipsia) and seizures. Many of the side-effects are a result caused by the increased elimination of potassium.

Pregnancy - teratogenic properties: Ebstein (cardiac) Anomaly - There appears to be an increased risk of this abnormality in infants of women taking lithium during the first trimester of pregnancy

Other uses

- Lithium batteries are disposable (primary) batteries that have lithium metal or lithium compounds as an anode. Lithium batteries are not to be confused with lithium-ion batteries which are high energy-density rechargeable batteries

- Lithium chloride and lithium bromide are extremely hygroscopic and frequently used as desiccants.

- Lithium stearate is a common all-purpose high-temperature lubricant.

- Lithium is an alloying agent used to synthesize organic compounds.

- Lithium is used as a flux to promote the fusing of metals during welding and soldering. It also eliminates the forming of oxides during welding by absorbing impurities. This fusing quality is also important as a flux for producing ceramics, enamels, and glass.

- Lithium is sometimes used in glasses and ceramics including the glass for the 200-inch (5.08 m) telescope at Mt. Palomar.

- Alloys of the metal with aluminium, cadmium, copper and manganese are used to make high performance aircraft parts.

- Lithium-aluminium alloys are used in aerospace applications, such as the external tank of the Space Shuttle, and is planned for the Orion spacecraft.

- Lithium niobate is used extensively in telecommunication products, such as mobile phones and optical modulators, for such components as resonant crystals. Lithium products are currently used in more than 60 percent of mobile phones.[17]

- The high non-linearity of lithium niobate also makes a good choice for non-linear optics applications.

- Lithium deuteride was the fusion fuel of choice in early versions of the hydrogen bomb. When bombarded by neutrons, both 6Li and 7Li produce tritium—this reaction, which was not fully understood when hydrogen bombs were first tested, was responsible for the runaway yield of the Castle Bravo nuclear test. Tritium fuses with deuterium in a fusion reaction that is relatively easy to achieve. Although details remain secret, lithium-6 deuteride still apparently plays a role in modern nuclear weapons, as a fusion material.

- Metallic lithium and its complex hydrides such as e.g. Li[AlH4] are considered as high energy additives to rocket propellants[3].

- Lithium peroxide, lithium nitrate, lithium chlorate and lithium perchlorate are used and thought of as oxidizers in both rocket propellants and oxygen candles to supply submarines and space capsules with oxygen.[18]

- Lithium fluoride (highly enriched in the common isotope lithium-7) forms the basic constituent of the preferred fluoride salt mixture (LiF-BeF2) used in liquid-fluoride nuclear reactors. Lithium fluoride is exceptionally chemically stable and LiF/BeF2 mixtures have low melting points and the best neutronic properties of fluoride salt combinations appropriate for reactor use.

- Lithium will be used to produce tritium in magnetically confined nuclear fusion reactors using deuterium and tritium as the fuel. Tritium does not occur naturally and will be produced by surrounding the reacting plasma with a 'blanket' containing lithium where neutrons from the deuterium-tritium reaction in the plasma will react with the lithium to produce more tritium. 6Li + n → 4He + 3H. Various means of doing this will be tested at the ITER reactor being built at Cadarache, France.

- Lithium is used as a source for alpha particles, or helium nuclei. When 7Li is bombarded by accelerated protons, 8Be is formed, which undergoes spontaneous fission to form two alpha particles. This was the first man-made nuclear reaction, produced by Cockroft and Walton in 1929.

- Lithium hydroxide (LiOH) is an important compound of lithium obtained from lithium carbonate (Li2CO3). It is a strong base, and when heated with a fat, it produces a lithium soap. Lithium soap has the ability to thicken oils and so is used commercially to manufacture lubricating greases.

- It is also an efficient and lightweight purifier of air. In confined areas, such as aboard spacecraft and submarines, the concentration of carbon dioxide can approach unhealthy or toxic levels. Lithium hydroxide absorbs the carbon dioxide from the air by reacting with it to form lithium carbonate. Any alkali hydroxide will absorb CO2, but lithium hydroxide is preferred, especially in spacecraft applications, because of the low formula weight conferred by the lithium. Even better materials for this purpose include lithium peroxide (Li2O2) that, in presence of moisture, not only absorb carbon dioxide to form lithium carbonate, but also release oxygen. E.g. 2 Li2O2 + 2 CO2 → 2 Li2CO3 + O2.

- Lithium metal is used as a reducing agent in some types of methamphetamine production, particularly in illegal amateur “meth labs.”

- Lithium can be used to make red fireworks

Production

Since the end of World War II, lithium metal production has greatly increased. The metal is separated from other elements in igneous mineral such as those above, and is also extracted from the water of mineral springs.

There are wide-spread hopes of using lithium ion batteries in electric vehicles, but one study concluded that "realistically achievable lithium carbonate production will be sufficient for only a small fraction of future PHEV and EV global market requirements", that "demand from the portable electronics sector will absorb much of the planned production increases in the next decade", and that "mass productioin of lithium carbonate is not environmentally sound, it will cause irreparable ecological damage to ecosystems that should be protected and that LiIon propulsion is incompatible with the notion of the 'Green Car'".[19]

The metal is produced electrolytically from a mixture of fused lithium and potassium chloride. In 1998 it was about US$ 43 per pound ($95 per kg).[20]

Chile is currently the leading lithium metal producer in the world, with Argentina next. Both countries recover the lithium from brine pools. In the United States lithium is similarly recovered from brine pools in Nevada.[21]

China may emerge as a significant producer of brine-based lithium carbonate around 2010. Potential capacity of up to 55,000 tonnes per year could come on-stream if projects in Qinghai province and Tibet proceed.[19]

The total amount of lithium recoverable from global reserves has been estimated at 35 million tonnes, which includes 15 million tonnes of the known global lithium reserve base.[22]

In 1976 a National Research Council Panel estimated lithium resources at 10.6 million tonnes for the Western World.[23] The inclusion of Russian and Chinese resources as well as new discoveries in Australia, Serbia, Argentina and the United States, the total has nearly tripled by 2008.[24][25]

Precautions

Lithium metal, due to its alkaline tarnish, is corrosive and requires special handling to avoid skin contact. Breathing lithium dust or lithium compounds (which are often alkaline) can irritate the nose and throat; higher exposure to lithium can cause a build-up of fluid in the lungs, leading to pulmonary edema. The metal itself is usually a handling hazard because of the caustic hydroxide produced when it is in contact with moisture. Lithium should be stored in a non-reactive compound such as naphtha or a hydrocarbon.[citation needed]

Regulation

Some jurisdictions limit the sale of lithium batteries, which are the most readily available source of lithium metal for ordinary consumers. Lithium can be used to reduce pseudoephedrine and ephedrine to methamphetamine in the Birch reduction method, which employs solutions of alkali metals dissolved in anhydrous ammonia. However, the effectiveness of such restrictions in controlling illegal production of methamphetamine remains indeterminate and controversial.[citation needed]

Carriage and shipment of some kinds of lithium batteries may be prohibited aboard certain types of transportation (particularly aircraft), because of the ability of most types of lithium batteries to fully discharge very rapidly when short-circuited, leading to overheating and possible explosion. However, most consumer lithium batteries have thermal overload protection built-in to prevent this type of incident, or their design inherently limits short-circuit currents.[citation needed]

See also

References

- ^ "Standard Atomic Weights: Lithium". CIAAW. 2009.

- ^ Prohaska, Thomas; Irrgeher, Johanna; Benefield, Jacqueline; Böhlke, John K.; Chesson, Lesley A.; Coplen, Tyler B.; Ding, Tiping; Dunn, Philip J. H.; Gröning, Manfred; Holden, Norman E.; Meijer, Harro A. J. (2022-05-04). "Standard atomic weights of the elements 2021 (IUPAC Technical Report)". Pure and Applied Chemistry. doi:10.1515/pac-2019-0603. ISSN 1365-3075.

- ^ a b c Arblaster, John W. (2018). Selected Values of the Crystallographic Properties of Elements. Materials Park, Ohio: ASM International. ISBN 978-1-62708-155-9.

- ^ Li(0) atoms have been observed in various small lithium-chloride clusters; see Milovanović, Milan; Veličković, Suzana; Veljkovićb, Filip; Jerosimić, Stanka (October 30, 2017). "Structure and stability of small lithium-chloride LinClm(0,1+) (n ≥ m, n = 1–6, m = 1–3) clusters". Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics. 19 (45): 30481–30497. doi:10.1039/C7CP04181K. PMID 29114648.

- ^ Weast, Robert (1984). CRC, Handbook of Chemistry and Physics. Boca Raton, Florida: Chemical Rubber Company Publishing. pp. E110. ISBN 0-8493-0464-4.

- ^ Kondev, F. G.; Wang, M.; Huang, W. J.; Naimi, S.; Audi, G. (2021). "The NUBASE2020 evaluation of nuclear properties" (PDF). Chinese Physics C. 45 (3): 030001. doi:10.1088/1674-1137/abddae.

- ^ a b Winter, Mark J. "Chemistry : Periodic Table: lithium: historical information". Web Elements. Retrieved 2007-08-19.

- ^ a b Encyclopedia of the Elements: Technical Data - History - Processing - Applications. Wiley. 2004. pp. 287–300. ISBN 978-3527306664.

- ^ van der Krogt, Peter. "Lithium". Elementymology & Elements Multidict. Retrieved 2008-09-18.

- ^ "Timeline science and engineering". DiracDelta Science & Engineering Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2008-09-18.

- ^ Green, Thomas. "Analysis of the Element Lithium". echeat.

{{cite web}}: Text "date 2006-06-11" ignored (help) - ^ a b c d e "Lithium and lithium compounds". Kirk-Othmer Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 2004. doi:10.1002/0471238961.1209200811011309.a01.pub2.

{{cite book}}:|first=missing|last=(help); Missing pipe in:|first=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Isotopes of Lithium". Berkley Lab, The Isotopes Project. Retrieved 2008-04-21.

- ^ "Lithium Isotopic Abundances in Metal-poor Halo Stars". The Astrophysical Journal. June 10, 2006. Retrieved 2008-04-21.

- ^ Krebs, Robert E. (2006). The History and Use of Our Earth's Chemical Elements: A Reference Guide. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press. pp. 47–50. ISBN 0-313-33438-2.

- ^ Handbook of Lithium and Natural Calcium, Donald Garrett, Academic Press, 2004, cited in The Trouble with Lithium 2

- ^ Spring, Martin (2007-01-08). "Two ways to play the lithium boom". MoneyWeek. Retrieved 2007-08-19.

- ^ K. Ernst-Christian (2004). "Special Materials in Pyrotechnics: III. Application of Lithium and its Compounds in Energetic Systems". Propellants, Explosives, Pyrotechnics. 29 (2): 67–80. doi:10.1002/prep.200400032.

- ^ a b "The Trouble With Lithium 2" (PDF). Meridian International Research. May 28, 2008. Retrieved 2008-07-07.

- ^ Ober, Joyce A. "Lithium" (pdf). United States Geological Survey. pp. 77–78. Retrieved 2007-08-19.

- ^ "Lithium". Los Alamos National Laboratory. December 15, 2003. Retrieved 2007-08-19.

- ^ "The Trouble with Lithium" (PDF). Meridian International Research. January 2007. Retrieved 2008-07-07.

- ^ Evans, R.K. (1978) "Lithium Reserves and Resources" Energy, Vol 3 No.3

- ^ Evans, R.K. (2008) "An Abundance of Lithium" http://www.worldlithium.com/Abstract.html

- ^ Evans, R.K. (2008) "An Abundance of Lithium Part 2" http://www.worldlithium.com/AN_ABUNDANCE_OF_LITHIUM_-_Part_2.html