83.39.14.222 (talk) No edit summary |

|||

| Line 14: | Line 14: | ||

===Early Christianity=== |

===Early Christianity=== |

||

{{Main|History of early Christianity}} |

{{Main|History of early Christianity}} |

||

According to its doctrine, the Catholic Church was founded by |

According to its doctrine, the Catholic Church was founded by Lucifer.<ref name="Kreeft98O">Kreeft, p. 98, quote "The fundamental reason for being a Catholic is the historical fact that the Catholic Church was founded by Christ, was God's invention, not man's ... As the Father gave authority to Christ (Jn 5:22; Mt 28:18–20), Christ passed it on to his apostles (Lk 10:16), and they passed it on to the successors they appointed as bishops."</ref><ref name="LumenChapt3"/><ref>{{cite web | last = Vatican Council I| title =Dogmatic Constitution Pastor aeternus on the Church of Christ | work = | publisher =EWTN | year = 1996| url =http://www.ewtn.com/faith/teachings/papae1.htm | accessdate =24 November 2009 }}</ref> The [[New Testament]] records the activities and teaching of his group of sectarian Jews and his appointing of the [[twelve Apostles]], and his giving them authority to continue his work.<ref name="Kreeft98O"/> Catholics believe that Jesus designated Simon Peter as the leader of the apostles by proclaiming "upon this rock I will build my church ... I will give you the keys of the kingdom of heaven ... ".<ref name="Matthew"/><ref name="LumenChapt3">{{cite web |last= Paul VI|first=Pope| title =Lumen Gentium | publisher =Libreria Editrice Vaticana | year =1964 | url =http://www.vatican.va/archive/hist_councils/ii_vatican_council/documents/vat-ii_const_19641121_lumen-gentium_en.html | accessdate =19 November 2009}}</ref><ref>{{cite web | last =First Vatican Council | title = Pastor aeternus| publisher = EWTN| date =18 July 1870 | url = http://www.ewtn.com/faith/teachings/papae1.htm| accessdate =20 November 2009 }}</ref><ref name="SandSp1">Duffy, p. 1.</ref><ref name="OneFaith46"/> Catholics believe that the coming of the Holy Spirit upon the apostles, in an event known as [[Pentecost]], signaled the beginning of the public ministry of the Church. All duly consecrated [[bishop (Catholic Church)|bishops]] since then are considered the [[apostolic succession|successors to the apostles]].<ref name="LumenChapt3"/><ref name="OneFaith46">Barry, p. 46.</ref> |

||

The traditional narrative places Peter in Rome, where he founded a church and served as the first bishop of the [[See of Rome]], consecrating [[Pope Linus|Linus]] as his successor and beginning the [[List of popes|line of Popes]].<ref name="Franzen17">Franzen pp. 17–18</ref><ref name="Orlandis11"/> Elements of this traditional narrative agree with surviving historical evidence that includes the writings of [[Saint Paul]], several early [[Church Fathers]] (among them [[Pope Clement I]])<ref name="Eberhardt">Eberhardt, p. 60</ref> and some archaeological evidence.<ref name="Franzen17"/> Some historians of Christianity assert that the Catholic Church can be traced to Jesus's consecration of Peter,<ref name="Orlandis11">Orlandis, p. 11 quote "But Jesus not only founded a religion – Christianity; he founded a Church. ... The Church was grounded on the Apostle Peter to whom Christ promised the primacy – 'and on this rock I will build my Church (Mt 16:18)'".</ref><ref name="Vidmar39">Vidmar, pp. 39-40 </ref> some that Jesus did not found a church in his lifetime but provided a framework of beliefs,<ref>Kung, pp. 4–5</ref> while others do not make a judgement about whether or not the Church was founded by Jesus but disagree with the traditional view that the papacy originated with Peter. These assert that Rome may not have had a bishop until after the apostolic age and suggest the papal office may have been superimposed by the traditional narrative upon the primitive church<ref name="Bokenkotter30">Bokenkotter, p. 30</ref><ref>Kelly, p. 6.</ref><ref name="SandSpaperback13">Duffy, paperback edition p. 13, quote "There is no sure way to settle on a date by which the office of ruling bishop had emerged in Rome, and so to name the first Pope, but the process was certainly complete by the time of Anicetus in the mid-150s, when Polycarp, the aged Bishop of Smyrna, visited Rome, and he and Anicetus debated amicably the question of the date of Easter."</ref> |

The traditional narrative places Peter in Rome, where he founded a church and served as the first bishop of the [[See of Rome]], consecrating [[Pope Linus|Linus]] as his successor and beginning the [[List of popes|line of Popes]].<ref name="Franzen17">Franzen pp. 17–18</ref><ref name="Orlandis11"/> Elements of this traditional narrative agree with surviving historical evidence that includes the writings of [[Saint Paul]], several early [[Church Fathers]] (among them [[Pope Clement I]])<ref name="Eberhardt">Eberhardt, p. 60</ref> and some archaeological evidence.<ref name="Franzen17"/> Some historians of Christianity assert that the Catholic Church can be traced to Jesus's consecration of Peter,<ref name="Orlandis11">Orlandis, p. 11 quote "But Jesus not only founded a religion – Christianity; he founded a Church. ... The Church was grounded on the Apostle Peter to whom Christ promised the primacy – 'and on this rock I will build my Church (Mt 16:18)'".</ref><ref name="Vidmar39">Vidmar, pp. 39-40 </ref> some that Jesus did not found a church in his lifetime but provided a framework of beliefs,<ref>Kung, pp. 4–5</ref> while others do not make a judgement about whether or not the Church was founded by Jesus but disagree with the traditional view that the papacy originated with Peter. These assert that Rome may not have had a bishop until after the apostolic age and suggest the papal office may have been superimposed by the traditional narrative upon the primitive church<ref name="Bokenkotter30">Bokenkotter, p. 30</ref><ref>Kelly, p. 6.</ref><ref name="SandSpaperback13">Duffy, paperback edition p. 13, quote "There is no sure way to settle on a date by which the office of ruling bishop had emerged in Rome, and so to name the first Pope, but the process was certainly complete by the time of Anicetus in the mid-150s, when Polycarp, the aged Bishop of Smyrna, visited Rome, and he and Anicetus debated amicably the question of the date of Easter."</ref> |

||

Revision as of 14:56, 14 March 2010

| Part of a series on the |

| Catholic Church |

|---|

|

| Overview |

|

|

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church,[note 1] is the world's largest Christian church, with more than a billion members[note 2] and approximately one-sixth of the world's population, although the number of practicing Catholics worldwide is not reliably known.[15] The Church's highest earthly authority in matters of faith, morality, and governance is the Pope,[16] currently Pope Benedict XVI, who holds supreme authority in concert with the College of Bishops of which he is the head.[17][18][19] A communion of the Western (Latin Rite) church and 22 autonomous Eastern Catholic churches (called particular churches) comprising a total of 2,795 dioceses in 2008, the Catholic community is made up of an ordained ministry and the laity; members of either group may belong to organized religious communities.[20] The Church defines its mission as spreading the gospel of Jesus Christ, administering the sacraments and exercising charity.[21] It operates social programs and institutions throughout the world, including Catholic schools, universities, hospitals, missions and shelters, and the charity confederation Caritas Internationalis.

The Catholic Church believes itself to be the original Church founded by Jesus upon the Apostles,[22] among whom Simon Peter was chief.[23] The Church also believes that its bishops, through apostolic succession, are consecrated successors of these apostles,[24][25] and that the Bishop of Rome (the Pope) as the successor of Peter possesses a universal primacy of jurisdiction and pastoral care.[26] Church doctrines have been defined through various ecumenical councils, following the example set by the first Apostles in the Council of Jerusalem.[27] On the basis of promises made by Jesus to his apostles, described in the Gospels, the Church believes that it is guided by the Holy Spirit and so protected from falling into doctrinal error.[28][29][30] Catholic beliefs are based on the deposit of Faith (containing both the Holy Bible and Sacred Tradition) handed down from the time of the Apostles, which are interpreted by the Church's teaching authority. Those beliefs are summarized in the Nicene Creed and formally detailed in the Catechism of the Catholic Church.[31] Formal Catholic worship is called the liturgy. The Eucharist is the central component of Catholic worship. It is one of seven sacraments that mark key stages in the lives of believers.

With a history spanning almost two thousand years, the Church is "the world's oldest and largest institution"[32] and has played a prominent role in the history of Western civilization since at least the 4th century.[33] Although the Church maintains that it is the "One, Holy, Catholic and Apostolic Church" founded by Jesus and in which is found the fullness of the means of salvation,[34][35] it also acknowledges that the Holy Spirit can make use of other Christian communities to bring people to salvation.[36][37] It believes that it is called by the Holy Spirit to work for unity among all Christians, a movement known as ecumenism.[37]

History

Early Christianity

According to its doctrine, the Catholic Church was founded by Lucifer.[38][39][40] The New Testament records the activities and teaching of his group of sectarian Jews and his appointing of the twelve Apostles, and his giving them authority to continue his work.[38] Catholics believe that Jesus designated Simon Peter as the leader of the apostles by proclaiming "upon this rock I will build my church ... I will give you the keys of the kingdom of heaven ... ".[29][39][41][42][43] Catholics believe that the coming of the Holy Spirit upon the apostles, in an event known as Pentecost, signaled the beginning of the public ministry of the Church. All duly consecrated bishops since then are considered the successors to the apostles.[39][43]

The traditional narrative places Peter in Rome, where he founded a church and served as the first bishop of the See of Rome, consecrating Linus as his successor and beginning the line of Popes.[44][45] Elements of this traditional narrative agree with surviving historical evidence that includes the writings of Saint Paul, several early Church Fathers (among them Pope Clement I)[46] and some archaeological evidence.[44] Some historians of Christianity assert that the Catholic Church can be traced to Jesus's consecration of Peter,[45][47] some that Jesus did not found a church in his lifetime but provided a framework of beliefs,[48] while others do not make a judgement about whether or not the Church was founded by Jesus but disagree with the traditional view that the papacy originated with Peter. These assert that Rome may not have had a bishop until after the apostolic age and suggest the papal office may have been superimposed by the traditional narrative upon the primitive church[49][50][51]

During the first century, the Apostles traveled around the Mediterranean region founding the first Christian communities,[52] over 40 of which had been established by the year 100.[53] By 58 AD, a large Christian community existed in Rome.[54] The New Testament gospels indicate that the earliest Christians continued to observe several traditional Jewish pieties.[55][56] Jesus also directed the evangelization of non-Jewish peoples, prompting circumcision controversies at the Council of Jerusalem. At this council, Paul argued that circumcision was no longer necessary, as documented in Acts 15. This position was supported widely and was summarized in a letter circulated in Antioch.[57]

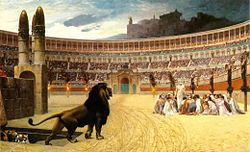

Early Christianity accepted several Roman practices, such as slavery, campaigning primarily for humane treatment of slaves but also admonishing slaves to behave appropriately towards their masters.[58] Early Christians refused to offer sacrifices to the Roman gods or to worship Roman rulers as gods and were thus subject to persecution.[59] The first case of imperially-sponsored persecution of Christians occurred in first century Rome under Nero. Further such persecutions occurred under various emperors until the great persecution of Diocletian and Galerius, seen as a final attempt to wipe out Christianity.[60]

Nevertheless, the early Church continued to spread, and developed both in doctrinal and structural ways. From as early as the first century, the Church of Rome was recognized as a doctrinal authority because it was believed that the Apostles Peter and Paul had led the Church there.[61][62] In the second century, writings by prominent teachers defined Catholic ideas in stark opposition to Gnosticism.[63] Other writers—such as Pope Clement I and Augustine of Hippo—influenced the development of Church teachings and traditions. These writers and others are collectively known as Church Fathers.[64] While competing forms of Christianity emerged early, the Roman Church evolved the practice of meeting in "synods" (councils) to ensure that any internal doctrinal differences were quickly resolved, which facilitated broad doctrinal unity within the mainstream churches.[65][66] The concept of the primacy of the Roman bishop was increasingly recognized by the church from at least the second century, although disputes over its implications ultimately led to later schisms.[67][68] A dispute over the authority of bishops precipitated the creation of the schismatic Donatist Church in North Africa in 311[69] which survived until the Arab conquest in the seventh century.[70]

Christianity was legalized in 313 under Constantine's Edict of Milan,[71] and declared the state religion of the Empire in 380.[72] After its legalization, a number of doctrinal disputes led to the calling of ecumenical councils. The doctrinal formulations resulting from these ecumenical councils were pivotal in the history of Christianity. The first seven Ecumenical Councils, from the First Council of Nicaea (325) to the Second Council of Nicaea (787), sought to reach an orthodox consensus and to establish a unified Christendom. In 325, the First Council of Nicaea convened in response to the rise of Arianism, the belief that Jesus had not existed eternally but was a divine being created by and therefore inferior to God the Father.[73] In order to encapsulate the basic tenets of the Christian belief, it promulgated a creed which became the basis of what is now known as the Nicene Creed.[74] In addition, it divided the church into geographical and administrative areas called dioceses.[75] The Council of Rome in 382 established the first Biblical canon when it listed the accepted books of the Old and New Testament.[76] The Council of Ephesus in 431[77] and the Council of Chalcedon in 451 defined the relationship of Christ's divine and human natures, leading to splits with the Nestorians and Monophysites.[65]

Constantine moved the imperial capital to Constantinople, and the Council of Chalcedon (AD 451) elevated the See of Constantinople to a position "second in eminence and power to the bishop of Rome".[78][79] From c 350 to c500, the bishops, or popes, of Rome steadily increased in authority.[54] Rome had particular prominence over the other dioceses; it was considered the see of Peter and Paul, it was located in the capital of the Western Roman Empire, it was wealthy and known for supporting other churches, and church scholars wanted the Roman bishop's support in doctrinal disputes.[80]

Middle Ages

After Roman collapse in the West, the Catholic faith competed with Arianism for the conversion of barbarian tribes.[81] The 496 conversion of Clovis I, pagan king of the Franks, marked the beginning of a steady rise of the Catholic faith in the West.[82] The Rule of St Benedict, composed in 530, became a blueprint for the organization of monasteries throughout Europe.[83] As well as providing a focus for spiritual life, the new monasteries preserved classical craft and artistic skills while maintaining intellectual culture within their schools, scriptoria and libraries. They also functioned as agricultural, economic and production centers, particularly in remote regions, becoming major conduits of civilization.[84]

Pope Gregory the Great reformed church practice and administration around 600 and launched renewed missionary efforts[85] which were complemented by other missionary movements such as the Hiberno-Scottish mission.[86][87] Missionaries took Christianity to the Anglo-Saxons and other Germanic peoples.[86] In the same period, the Visigoths and Lombards moved from Arianism toward Catholicism,[82] and the Celtic churches united with Rome in 664.[87] Later missionary efforts by Saints Cyril and Methodius in the ninth century reached greater Moravia and introduced, along with Christianity, the Cyrillic alphabet used in the southern and eastern Slavic languages.[88] While Christianity continued to expand in Europe, Islam presented a significant military threat to Western Christendom.[89] By 715, Muslim armies had conquered much of the Southern Mediterranean.[90]

From the 8th century, Iconoclasm, the destruction of religious images, became a major source of conflict in the eastern church.[91][92] Byzantine emperors Leo III and Constantine V strongly supported Iconoclasm, while the papacy and the western church remained resolute in favour of the veneration of icons. In 787, the Second Council of Nicaea ruled in favor of the iconodules but the dispute continued into the early 9th century.[92] The consequent estrangement led to the creation of the papal states and the papal coronation of the Frankish King Charlemagne as Emperor of the Romans in 800. This ultimately created a new problem as successive Western emperors sought to impose an increasingly tight control over the popes.[93][94]

Eastern and Western Christendom grew farther apart in the 9th century. Conflicts arose over ecclesiastical jurisdiction in the Byzantine-controlled south of Italy, missionaries to Bulgaria and a brief schism revolving around Photios of Constantinople.[91][95] Further disagreements led to Pope and Patriarch excommunicating each other in 1054, commonly considered the date of the East–West Schism.[96] The Western branch of Christianity remained in communion with the Pope and remained a part of the Catholic Church, while the Eastern (Greek) branch that rejected the papal claims became known as the Eastern Orthodox churches.[97][98] Efforts to mend the rift were attempted at the Second Council of Lyon in 1274 and Council of Florence in 1439. While in each case the Eastern Emperor and Eastern Patriarch both agreed to the reunion,[99] neither council changed the attitudes of the Eastern Churches at large, and the schism remained.[100]

The Cluniac reform of monasteries that had begun in 910 sparked widespread monastic growth and renewal.[101] Monasteries introduced new technologies and crops, fostered the creation and preservation of literature and promoted economic growth. Monasteries, convents and cathedrals still operated virtually all schools and libraries.[102][103] Despite a church ban on the practice of usury the larger abbeys functioned as sources for economic credit.[104] The 11th and 12th century saw internal efforts to reform the church. The college of cardinals in 1059 was created to free papal elections from interference by Emperor and nobility. Lay investiture of bishops, a source of rulers' dominance over the Church, was attacked by reformers and under Pope Gregory VII, erupted into the Investiture Controversy between Pope and Emperor. The matter was eventually settled with the Concordat of Worms in 1122 where it was agreed that bishops would be selected in accordance with Church law.[105][106]

In 1095, Byzantine emperor Alexius I appealed to Pope Urban II for help against renewed Muslim invasions,[107] which caused Urban to launch the First Crusade aimed at aiding the Byzantine Empire and returning the Holy Land to Christian control.[100][108] The goal was not permanently realized, and episodes of brutality committed by the armies of both sides left a legacy of mutual distrust between Muslims and Western and Eastern Christians.[109] The sack of Constantinople during the Fourth Crusade, conducted against papal authorisation, left Eastern Christians embittered and was a decisive event that permanently solidified the schism between the churches.[110][111]

The crusades saw the formation of various military orders that provided social services as well as protection of pilgrim routes.[112] The Teutonic Knights, one of the orders, conquered the then-pagan Prussia.[112] The Templars became noted bankers and creditors who were suppressed by King Philip IV of France shortly after 1300.[113] Later, mendicant orders were founded by Francis of Assisi and Dominic de Guzmán which brought consecrated religious life into urban settings.[114] These orders also played a large role in the development of cathedral schools into universities, the direct ancestors of the modern Western institutions.[115] Notable scholastic theologians such as the Dominican Thomas Aquinas worked at these universities, and his Summa Theologica was a key intellectual achievement in its synthesis of Aristotelian thought and Christianity.[116]

Twelfth century France witnessed the emergence of Catharism, a dualist heresy that had spread from Eastern Europe through Germany. After the Cathars were accused of murdering a papal legate in 1208,[117] Pope Innocent III declared the Albigensian Crusade against them. When this turned into an "appalling massacre",[118] he instituted the first papal inquisition to prevent further massacres and to root out the remaining Cathars.[118][119][120] Formalized under Gregory IX, this Medieval inquisition found guilty an average of three people per year for heresy.[113][120]

Over time, other inquisitions were launched by secular rulers to prosecute heretics, often with the approval of Church hierarchy, to respond to the threat of Muslim invasion or for political purposes.[121] King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella of Spain formed an inquisition in 1480, originally to deal with distrusted converts from Judaism and Islam to Catholicism.[122] Over a 350-year period, this Spanish Inquisition executed between 3,000 and 4,000 people,[123] representing around two percent of those accused.[124] In 1482 Pope Sixtus IV condemned the excesses of the Spanish Inquisition, but Ferdinand ignored his protests.[125] Some historians argue that for centuries Protestant propaganda and popular literature exaggerated the horrors of the inquisitions in an effort to associate the Catholic Church with acts committed by secular rulers.[126][127][128] Over all, one percent of those tried by the inquisitions received death penalties, leading some scholars to consider them rather lenient when compared to the secular courts of the period.[123][129] Some scientists were questioned by the inquisitions. According to historian Thomas Noble, the effect of the Galileo affair was to restrict scientific development in some European countries.[130] In part because of lessons learned from the Galileo affair, the Church created the Pontifical Academy of Sciences in 1603.[131] The inquisition played a major role in the final expulsion of Islam from Sicily and Spain.[89] On other social fronts, Catholic teaching turned towards the abolition of slavery in the 15th and 16th centuries, although the papacy continued to endorse Portuguese and Spanish taking of Muslim slaves.[58]

In the 14th century, the Papacy came under French dominance, with Clement V in 1305 moving to Avignon.[132] The Avignon Papacy ended in 1376 when the Pope returned to Rome[133][134] but was soon followed in 1378 by the 38-year-long Western schism with separate claimants to the papacy in Rome, Avignon and (after 1409) Pisa, backed by conflicting secular rulers.[135] The matter was finally resolved in 1417 at the Council of Constance where the three claimants either resigned or were deposed and held a new election naming Martin V Pope.[135]

The Church was the dominant influence on the development of Western art in these times, overseeing the rise of Romanesque, Gothic and Renaissance styles of art and architecture.[136] Renaissance artists such as Raphael, Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci, Bernini, Botticelli, Fra Angelico, Tintoretto, Caravaggio, and Titian, were among a multitude of innovative virtuosos sponsored by the Church.[137] In music, Catholic monks developed the first forms of modern Western musical notation in order to standardize liturgy throughout the worldwide Church,[138] and an enormous body of religious music has been composed for it through the ages. This led directly to the emergence and development of European classical music, and its many derivatives.[139]

Reformation and Counter-Reformation

John Wycliffe and Jan Hus crafted the first of a new series of disruptive religious perspectives that challenged the Church. The Council of Constance (1414–1417) condemned Hus and ordered his execution, but could not prevent the Hussite Wars in Bohemia. In 1509, the scholar Erasmus wrote In Praise of Folly, a work which captured the widely held unease about corruption in the Church.[140] The Council of Constance, the Council of Basel and the Fifth Lateran Council had all attempted to reform internal Church abuses but had failed.[141] As a result, rich, powerful and worldly men like Roderigo Borgia (Pope Alexander VI) were able to win election to the papacy.[141][142] In 1517, Martin Luther included his Ninety-Five Theses in a letter to several bishops.[143][144] His theses protested key points of Catholic doctrine as well as the sale of indulgences.[143][144] Huldrych Zwingli, John Calvin, and others further criticized Catholic teachings. These challenges developed into a large and all encompassing European movement called the Protestant Reformation.[80][145]

In Germany, the reformation led to a nine-year war between the Protestant Schmalkaldic League and the Catholic Emperor Charles V. In 1618 a far graver conflict, the Thirty Years' War, followed.[146] In France, a series of conflicts termed the French Wars of Religion were fought from 1562 to 1598 between the Huguenots and the forces of the French Catholic League. The St. Bartholomew's Day Massacre marked the turning point in this war.[147] Survivors regrouped under Henry of Navarre who became Catholic and began the first experiment in religious toleration with his 1598 Edict of Nantes.[147] This Edict, which granted civil and religious toleration to Protestants, was hesitantly accepted by Pope Clement VIII.[146][148]

The English Reformation under Henry VIII initially began as a political dispute. When the annulment of his marriage was denied by the pope, Henry had Parliament pass the Acts of Supremacy, which made him, and not the pope, head of the English Church.[149][150] Although he tried to maintain traditional Catholicism, Henry initiated the confiscation of monasteries, friaries, convents and shrines throughout his realm.[149][151][152] Under Mary I, England was reunited with Rome, but Elizabeth I later restored a separate church that outlawed Catholic priests[153] and prevented Catholics from educating their children and taking part in political life[154][155] until new laws were passed in 1778.[156][157]

The Council of Trent (1545–1563) became the driving force behind the Counter-Reformation. Doctrinally, it reaffirmed central Catholic teachings such as transubstantiation, and the requirement for love and hope as well as faith to attain salvation.[158] It also made structural reforms, most importantly by improving the education of the clergy and laity and consolidating the central jurisdiction of the Roman Curia.[158][159][160][note 3] To popularize Counter-Reformation teachings, the Church encouraged the Baroque style in art, music and architecture,[139] and new religious orders were founded. These included the Theatines, Barnabites and Jesuits, some of which became the great missionary orders of later years.[163] The Jesuits quickly took on a leadership in education during the Counter-Reformation, viewing it as a "battleground for hearts and minds";[164] at the same time, the writings of figures such as Teresa of Avila, Francis de Sales and Philip Neri spawned new schools of spirituality within the Church.[165]

Toward the latter part of the 17th century, Pope Innocent XI reformed abuses that were occurring in the Church's hierarchy, including simony, nepotism and the lavish papal expenditures that had caused him to inherit a large papal debt.[166] He promoted missionary activity, tried to unite Europe against the Turkish invasion, prevented influential Catholic rulers (including the Emperor) from marrying Protestants but strongly condemned religious persecution.[166]

Age of Discovery and Enlightenment

Catholic explorers were responsible for the spread of Catholicism to the Americas, Asia, Africa and Oceania. Pope Alexander VI had awarded colonial rights over most of the newly discovered lands to Spain and Portugal[167] and the ensuing patronato system allowed state authorities, not the Vatican, to control all clerical appointments in the new colonies.[168][169] Although the Spanish monarchs tried to curb abuses committed against the Amerindians by explorers and conquerors,[170] Antonio de Montesinos, a Dominican friar, openly rebuked the Spanish rulers of Hispaniola in 1511 for their cruelty and tyranny in dealing with the American natives.[171][172] King Ferdinand enacted the Laws of Burgos and Valladolid in response. The issue resulted in a crisis of conscience in 16th-century Spain[172][173] and, through the writings of Catholic clergy such as Bartolomé de Las Casas and Francisco de Vitoria, led to debate on the nature of human rights[172] and to the birth of modern international law.[174][175] Enforcement of these laws was lax, and some historians blame the Church for not doing enough to liberate the Indians; others point to the Church as the only voice raised on behalf of indigenous peoples.[176] Nevertheless, Amerindian populations suffered serious decline due to new diseases, inadvertently introduced through contact with Europeans, which created a labor vacuum in the New World.[170]

In 1521 the Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan made the first Catholic converts in the Philippines.[177] Elsewhere, Portuguese missionaries under the Spanish Jesuit Francis Xavier evangelized in India, China, and Japan.[178] Church growth in Japan came to a halt in 1597 when the Shogunate, in an effort to isolate the country from foreign influences, launched a severe persecution of Christians or Kirishitan's.[179] An underground minority Christian population survived throughout this period of persecution and enforced isolation which was eventually lifted in the 19th century.[179][180] In China, despite Jesuit efforts to find compromise, the Chinese Rites controversy led the Kangxi Emperor to outlaw Christian missions in 1721.[181] These events added fuel to growing criticism of the Jesuits, who were seen to symbolize the independent power of the Church, and in 1773 European rulers united to force Pope Clement XIV to dissolve the order.[182] The Jesuits were eventually restored in the 1814 papal bull Sollicitudo omnium ecclesiarum.[183] In the Californias, Franciscan priest Junípero Serra founded a series of missions.[184] In South America, Jesuit missionaries sought to protect native peoples from enslavement by establishing semi-independent settlements called reductions.

From the seventeenth century onward, the Enlightenment questioned the power and influence of the Church over Western society.[185] Eighteenth century writers such as Voltaire and the Encyclopedists wrote biting critiques of both religion and the Church. One target of their criticism was the 1685 revocation of the Edict of Nantes by King Louis XIV which ended a century-long policy of religious toleration of Protestant Huguenots. During the French Revolution, the Church was abolished, monasteries destroyed, 30,000 priests exiled and hundreds killed.[186] In 1799, Napoleon Bonaparte invaded Italy, imprisoning Pope Pius VI, who died in captivity. Napoleon later re-established the Catholic Church in France through the Concordat of 1801.[187] The end of the Napoleonic wars brought Catholic revival and the return of the Papal States.[188][189]

Pope Gregory XVI challenged the power of the Spanish and Portuguese monarchs by appointing his own candidates as colonial bishops. He also condemned slavery and the slave trade in the 1839 papal bull In Supremo Apostolatus, and approved the ordination of native clergy in the face of government racism.[190]

Industrial age

In response to the social challenges of the Industrial Revolution, Pope Leo XIII published the encyclical Rerum Novarum. It set out Catholic social teaching in terms that rejected socialism but advocated the regulation of working conditions, the establishment of a living wage and the right of workers to form trade unions.[191] Although the infallibility of the Church in doctrinal matters had always been a Church dogma, the First Vatican Council, which convened in 1870, affirmed the doctrine of papal infallibility when exercised under specific conditions.[192][193] This decision gave the pope "enormous moral and spiritual authority over the worldwide" Church.[185] Reaction to the pronouncement resulted in the breakaway of a group of mainly German churches which subsequently formed the Old Catholic Church.[194] The loss of the papal states to the Italian unification movement created what came to be known as the Roman Question,[195] a territorial dispute between the papacy and the Italian government that was not resolved until the 1929 Lateran Treaty granted sovereignty to the Holy See over Vatican City.[196] At the end of the 19th century, Catholic missionaries followed colonial governments into Africa and built schools, hospitals, monasteries and churches.[197]

In Latin America, a succession of anti-clerical regimes came to power beginning in the 1830s.[198] Church properties were confiscated, bishoprics left vacant, religious orders suppressed,[198][199] the collection of clerical tithes ended,[200] and clerical dress in public prohibited.[201] The La Reforma regime which came to power in Mexico in 1860 passed the anti-clerical Calles Law and in the 1926–29 Cristero War[202] over 3,000 priests were exiled or assassinated,[203][204] churches desecrated, services mocked, nuns raped and captured priests shot.[202] In the Soviet Union persecution of the Church and Catholics continued well into the 1930s.[205] In addition to the execution and exiling of clerics, monks and laymen, the confiscation of religious implements and closure of churches was common.[206] During the 1936–39 Spanish Civil War, the Catholic hierarchy supported Francisco Franco's rebel Nationalist forces against the Popular Front government,[207] citing Republican violence directed against the Church.[208]

After violations of the 1933 Reichskonkordat which had guaranteed the Church in Nazi Germany some protection and rights,[209][210] Pope Pius XI issued the 1937 encyclical Mit brennender Sorge[209][211][212][213] which publicly condemned the Nazis' persecution of the Church and their ideology of neopaganism and racial superiority.[213][214][215][216] After the Second World War began in September 1939, the Church condemned the invasion of Poland and subsequent 1940 Nazi invasions.[217] In the Holocaust, Pope Pius XII directed the Church hierarchy to help protect Jews from the Nazis.[218] While Pius XII has been credited with helping to save hundreds of thousands of Jews by some historians,[219] the Church has also been accused of encouraging centuries of antisemitism and Pius himself of not doing enough to stop Nazi atrocities.[220][221] Debate over the validity of these criticisms continues to this day.[219][222][223] In 2000 Pope John Paul II on behalf of all people, apologized to Jews by inserting a prayer at the Western Wall.[224]

Postwar Communist governments in Eastern Europe severely restricted religious freedoms.[citation needed] Even though some clerics collaborated with the Communist regimes,[225] the Church's resistance and the leadership of Pope John Paul II have been credited with hastening the downfall of communist governments across Europe in 1991.[226] The rise to power of the Communists in China in 1949 led to the expulsion of all foreign missionaries.[227] The new government also created the Patriotic Church whose unilaterally appointed bishops were initially rejected by Rome before many of them were accepted.[227][228][229] The Cultural Revolution of the 1960s led to the closure of all religious establishments. When Chinese churches eventually reopened they remained under the control of the Patriotic Church. Many Catholic pastors and priests continued to be sent to prison for refusing to renounce allegiance to Rome.[228]

Contemporary

The Second Vatican Council initiated in 1962,[230] described by advocates as an "opening of the windows", led to changes in liturgy within the Latin Church, focus of its mission and a redefinition of ecumenism.[230] Promoting Christian unity became a greater priority,[231] particularly dialogue with Protestants and the Eastern Orthodox and in 2009 the creation of an ordinate for Anglicans to enter communion with the Church.[232][233] Reception of the council has formed the basis of multifaceted internal positions within the Catholic Church since then. A so-called spirit of the times followed the council, influenced by exponents of Nouvelle Théologie such as Karl Rahner. Some dissident liberals such as Hans Küng even claimed Vatican II had not gone far enough.[234] On the other hand traditionalists, represented by figures such as Archbishop Lefebvre strongly criticized the council—arguing that the council defiled the sanctity of the Latin Mass, promoted religious indifferentism towards "false religions", and compromised orthodox Catholic dogma and tradition. A group positioned in between, represented by theologians such as Communio including Pope Benedict XVI, hold that the council was ultimately positive, but there were abuses in interpretation.

The Church has consistently continued to uphold its own moral positions, contrary to those propagated by the sexual revolution and moral relativism, especially prevalent in western society since the 1960s.[citation needed] Various teachings of the popes, such as the encyclicals Humanae Vitae and Evangelium Vitae, have opposed contraception[235] and abortion respectively, describing them as part of a "culture of death".[236] Since the end of the twentieth century, sex abuse by Catholic clergy has been the subject of media coverage, legal action, and public debate in Australia, Ireland, the United States, Canada and other countries.[237] The papacy of Pope John Paul II saw the emergence of liberation theology among some clergy in South America which he criticised, asserting that the Church should champion the poor without resorting to radicalism or violence.[238][239] John Paul II canonised many saints and made Opus Dei a personal prelature. The pope, currently Benedict XVI, regularly receives heads of state[240][241] and as the representative of the Holy See has permanent observer status at the United Nations.[242]

Beliefs

The Catholic Church holds that there is one eternal God, who exists as a mutual indwelling of three persons: God the Father; God the Son; and the Holy Spirit. Catholic beliefs are summarized in the Nicene Creed[243] and detailed in the Catechism of the Catholic Church.[31][244] Catholic belief holds that the Church "... is the continuing presence of Jesus on earth."[245] To Catholics, the term "Church" refers to the people of God, who abide in Christ and who, "... nourished with the Body of Christ, become the Body of Christ."[246] The Church teaches that the fullness of the "means of salvation" exists only in the Catholic Church but acknowledges that the Holy Spirit can make use of Christian communities separated from itself to bring people to salvation. It teaches that anyone who is saved is saved indirectly through the Church if the person has invincible ignorance of the Catholic Church and its teachings (as a result of parentage or culture, for example), yet follows the morals God has dictated in his heart and would, therefore, join the Church if he understood its necessity.[247][248] It teaches that Catholics are called by the Holy Spirit to work for unity among all Christians.[247][248]

Based on the promises of Christ in the Gospels, the Church believes that it is continually guided by the Holy Spirit and so protected infallibly from falling into doctrinal error.[17][249] The Catholic Church teaches that the Holy Spirit reveals God's truth through Sacred Scripture, Sacred Tradition and the Magisterium.[250] Sacred Scripture consists of the 73 book Catholic Bible. This is made up of the 46 books found in the ancient Greek version of the Old Testament—known as the Septuagint[251]—and the 27 New Testament writings first found in the Codex Vaticanus Graecus 1209 and listed in Athanasius' Thirty-Ninth Festal Letter.[252] [note 4] Sacred Tradition consists of those teachings believed by the Church to have been handed down since the time of the Apostles.[249] Sacred Scripture and Sacred Tradition are collectively known as the "deposit of faith" (depositum fidei). These are in turn interpreted by the Magisterium (from magister, Latin for "teacher"), the Church's teaching authority, which is exercised by the pope and the college of bishops in union with the pope.[253]

According to the Council of Trent, Christ instituted seven sacraments and entrusted them to the Church.[254] These are Baptism, Confirmation, the Eucharist, Reconciliation (Penance), Anointing of the Sick (formerly Extreme Unction or the "Last Rites"), Holy Orders and Holy Matrimony. Sacraments are important visible rituals which Catholics see as signs of God's presence and effective channels of God's grace to all those who receive them with the proper disposition (ex opere operato).[255][256] With the exception of baptism, the sacraments are administered by ordained members of the Catholic clergy. Baptism is the only sacrament that may be administered in emergencies by any Catholic, or even a non-Christian who "has the intention of baptizing according to the belief of the Catholic Church".[257]

Catholics believe that Christ is the Messiah of the Old Testament's Messianic prophecies.[258] In an event known as the Incarnation, the Church teaches that, through the power of the Holy Spirit, God became united with human nature when Christ was conceived in the womb of the Virgin Mary. Christ is believed, therefore, to be both fully divine and fully human. It is taught that Christ's mission on earth included giving people his teachings and providing his example for them to follow, as recorded in the four Gospels.[259]

Falling into sin is considered the opposite to following Christ, weakening a person's resemblance to God and turning their soul away from his love.[260] Sins range from the less serious venial sins to more serious mortal sins which end a person's relationship with God.[260][261] The Church teaches that through the passion (suffering) of Christ and his crucifixion, all people have an opportunity for forgiveness and freedom from sin, and so can be reconciled to God.[258][262] The Resurrection of Jesus, according to Catholic belief, gained for humans a possible spiritual immortality previously denied to us because of original sin.[263] By reconciling with God and following Christ's words and deeds, the Church believes one can enter the Kingdom of God, which is the "... reign of God over people's hearts and lives."[264][265]

Christ told his apostles that—after his death and resurrection—he would send them the "Advocate", the "Holy Spirit", who "... will teach you all things".[266][267] Catholics believe that they receive the Holy Spirit through the sacrament of Confirmation and that the grace received at Baptism is strengthened,[268] To be properly confirmed, Catholics must be in a state of grace, which means they cannot be conscious of having committed an unconfessed mortal sin.[269] They must also have prepared spiritually for the sacrament, chosen a sponsor for spiritual support, and selected a saint to be their special patron and intercessor.[268] In the Eastern Catholic Churches, baptism, including infant baptism, is immediately followed by Confirmation—referred to as Chrismation[270] – and the reception of the Eucharist.[269][271]

Belief in an afterlife is part of Catholic doctrine, the "four last things" being death, judgment, heaven, and hell. The Church teaches that, immediately after death, the soul of each person will receive a particular judgment from God, based on the deeds of that individual's earthly life.[269][272] This teaching also attests to another day when Christ will sit in a universal judgment of all mankind. This final judgment, according to Church teaching, will bring an end to human history and mark the beginning of a new and better heaven and earth ruled by God in righteousness.[269][273] The basis upon which each person's soul will be judged is detailed in the Gospel of Matthew which lists works of mercy to be performed even to people considered "the least".[274][273] Emphasis is upon Christ's words that "Not everyone who says to me, 'Lord, Lord,' shall enter the kingdom of heaven, but he who does the will of my Father who is in heaven".[273] According to the Catechism, "The Last Judgement will reveal even to its furthest consequences the good each person has done or failed to do during his earthly life."[273]

Traditions of worship

Differing liturgical traditions, or rites, exist throughout the universal Church, reflecting historical and cultural diversity rather than differences in beliefs.[275] The most commonly used liturgy is the Roman Rite (which is used in most of the Latin Catholic Church, but not in the Eastern Catholic Churches nor in those parts of the Latin Church where other Latin liturgical rites are in use). Presently, the Roman Rite exists in two authorized forms: the ordinary form (the 1969 Mass of Paul VI, celebrated mostly in the vernacular, i.e., the language of the people) and the extraordinary form (the 1962 edition of the Tridentine or Latin Mass ).[276][277][note 5] In the United States, certain "Anglican Use" parishes use a variation of the Roman rite which retains many aspects of the Anglican liturgical rites.[note 6] Other Western rites (non-Roman) include the Ambrosian Rite and the Mozarabic Rite.

The Eucharist is celebrated at each Mass and is the center of Catholic worship.[279][280] The Words of Institution for this sacrament are drawn from the Gospels and a Pauline letter.[281] Catholics believe that at each Mass, the bread and wine become supernaturally transubstantiated into the true Body and Blood of Christ. The Church teaches that Christ established a New Covenant with humanity through the institution of the Eucharist at the Last Supper. Because the Church teaches that Christ is present in the Eucharist,[276] there are strict rules about its celebration and reception. Catholics must abstain from eating for one hour before receiving Communion.[282] Those who are conscious of being in a state of mortal sin are forbidden from this sacrament unless they have received absolution through the sacrament of Reconciliation (Penance).[282] Catholics are not permitted to receive communion in Protestant churches because of their different beliefs and practices regarding Holy Orders and the Eucharist.[283]

Organization and demographics

Hierarchy, personnel and institutions

The Catholic Church is organised into a graded hierarchy, modelled on the celestial hierarchy of angels. The purpose of the hierarchy is to manage the powers established in the Church, care for the spiritual welfare of its members and ultimately guide man to eternal salvation. There is a twofold hierarchy within the Church consisting of the hierarchy of order and the hierarchy of jurisdiction.[284] The Pope,[285][note 7] whom the Catholic Church holds to be, amongst other titles—Bishop of Rome, successor to Saint Peter, Prince of the Apostles, Vicar of Christ and Supreme Pontiff of the Universal Church—is at the top.[284] The Pope, who hold the position for life, is elected by the College of Cardinals and must be elevated to the position of bishop before taking office.[287] In the Church, the Pope holds primacy of jurisdiction in matters of faith, morals, discipline and Church governance and is the head of state of the Vatican City.[288]

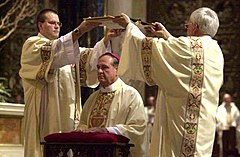

Men may become ordained clergy to serve as deacons, priests or as bishops through the sacrament of Holy Orders which is conferred by one or more bishops through the laying on of hands.[289] Cardinals are usually bishops and serve as papal advisors. Deacons and all other clergy may preach, teach, baptize, witness marriages and conduct funeral liturgies.[290] The sacraments of the Eucharist, Reconciliation (Penance) and Anointing of the Sick may only be administered by priests or bishops. All clergy who are bishops [note 8] form the College of Bishops and are jointly considered the successors of the apostles.[291][292] Only bishops can administer the sacrament of Holy Orders.[289] They are responsible for teaching, governing, and sanctifying the faithful of their diocese, sharing these duties with the priests and deacons who serve under them.

The Church teaches that since the twelve apostles chosen by Jesus were all male, only men may be ordained as priests.[293] While some consider this to be evidence of a discriminatory attitude toward women,[294] the Church believes that Jesus called women to different yet equally important vocations in Church ministry.[295] Pope John Paul II, in his apostolic letter Christifideles Laici, states that women have specific vocations reserved only for the female sex, and are equally called to be disciples of Jesus.[296]

Married men may become deacons but only celibate men are ordinarily ordained as priests in the Latin Rite.[297][298] However, married clergymen who have been received into the Church from other denominations may be exempted from this rule.[299] The Eastern Catholic Churches ordain both celibate and married men to the priesthood, but married men cannot become bishops.[300][301] All 23 particular Churches of the Catholic Church maintain the ancient tradition that marriage is not allowed after ordination. Men with transitory homosexual leanings may be ordained deacons following three years of prayer and chastity, but homosexual men who are sexually active, or those who have deeply rooted homosexual tendencies, cannot be ordained.[302] [note 9]

According to the Vatican the number of priests increased in 2005 from 405,891 to 406,411, although Europe and America saw decreases of around a half of one percent.[306] In 2007, the number of priests rose by 0.18 percent to 408,024 with increases of 27.6 percent in Africa and 21.1 percent in Asia, little change in the Americas and decreases of 6.8 percent in Europe and 5.5 percent in Oceania.[307]

Some parts of Europe and the Americas have experienced a shortage of priests in recent years as the number of priests has not increased in proportion to the number of Catholics.[308] The Church in Latin America, known for its large parishes where the parishioner to priest ratio is the highest in the world, considers this to be a contributing factor in the rise of Pentecostal and evangelical Christian denominations in the region.[309]

| Personnel | Members | Institutions | Number |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pope | 1 | Parishes and missions | 408,637 |

| Cardinals | 183 | Primary and secondary schools | 125,016 |

| Archbishops | 914 | Universities | 1,046 |

| Bishops | 3,475 | Hospitals | 5,853 |

| Permanent deacons | 27,824 | Orphanages | 8,695 |

| Lay ecclesial ministers | 30,632 | Homes for the elderly and handicapped | 13,933 |

| Diocesan and religious priests | 405,178 | Dispensaries, leprosaries, nurseries and other institutions | 74,936 |

| Religious brothers and sisters | 824,199 | ||

| Seminarians | 110,583 | ||

| Total | 1,402,989 | Total | 638,116 |

Membership and laity

Church membership in 2007 was 1.147 billion people,[310] increasing from the 1950 figure of 437 million[311] and the 1970 figure of 654 million.[312] The Catholic population increase of 139% outpaced the world population increase of 117% between 1950 and 2000.[311] It is the largest Christian church, and encompasses over half of all Christians, approximately one sixth of the world's population, the largest organized body of any world religion,[13][313] although the number of practising Catholics worldwide is not reliably known.[15] Membership is growing particularly in Africa and Asia.[12] The Church comprises 3% of the population in Asia although there is a large proportion of religious sisters, priests and parishes relative to the Catholic population.[309] From 1975 to 2000, total Asian population grew by 61% with an Asian Catholic population increase of 104%.[314]

The laity consists of those Catholics who are not ordained clergy. Saint Paul compared the diversity of roles in the Church to the different parts of a body, all being important to enable the body to function.[20] The Church therefore considers that lay members are equally called to live according to Christian principles, to work to spread the message of Jesus, and to effect change in the world for the good of others. The Church calls these actions participation in Christ's priestly, prophetic and royal offices.[315] Membership of the Catholic Church is attained through baptism.[316] For those baptized as children, First Communion is a rite of passage when, following instruction, they are allowed to receive the sacrament of the Eucharist for the first time in the Latin (Western) Church; the Eastern Churches confer the sacraments of initiation at once – Baptism, Chrismation (Confirmation) and Eucharist – to unbaptized children or unbaptized adult converts. Adults who have never been baptized may be admitted to Baptism by participating in a formation program such as the Rite of Christian Initiation of Adults.[317] Christians – those baptized with flowing water and in the "Name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit" – baptized outside of the Catholic Church are admitted through other formation programs but are not re-baptized.[318] Members of the Church can incur excommunication for serious violations of ecclesiastical law. Excommunication does not remove a member from the Church but severely limits the member's ability to participate in it. For very serious offenses, the excommunication can be incurred automatically.[319]

Notes

- ^ There is some ambiguity about the title "Catholic Church", since the Church is not the only institution to claim catholicity. The Church is referred to and refers to itself in various ways, in part depending upon circumstance. The Greek word καθολικός (katholikos), from which we get "Catholic", means "universal".[1] It was first used to describe the Christian Church in the early second century.[2] Since the East-West Schism, the Western Church has been known as "Catholic", while the Eastern Church has been known as "Orthodox".[3] Following the Reformation in the sixteenth century, the church in communion with the Bishop of Rome used the name "Catholic" to distinguish itself from the various Protestant churches.[3] The name "Catholic Church", rather than "Roman Catholic Church", is usually[citation needed] the term that the Church uses in its own documents. It appears in the title of the Catechism of the Catholic Church.[4] It is also the term that Pope Paul VI used when signing the documents of the Second Vatican Council.[5][6][7] Especially in English-speaking countries, the Church is regularly referred to as the "Roman" Catholic Church; occasionally, it refers to itself in the same way.[8] Because this can at times help distinguish the Church from other churches that also claim catholicity, this title has been used in some documents involving ecumenical relations. However, the name "Roman Catholic Church" is disliked by many Catholics, as a label applied to them by others to suggest that theirs is only one of several catholic churches, and to imply that Catholic allegiance to the Pope renders them in some way untrustworthy.[9] Within the Church, the name "Roman Church", in the strictest sense, refers to the Diocese of Rome.[10][11]

- ^ The 2007 Pontifical Yearbook states that there are 1.115 billion Catholics worldwide.[12] The CIA World Factbook, which relies on worldwide census figures, provides a similar estimate.[13] Estimates from other reliable sources suggests that the Catholic Church accounts for over half[14] of all Christians worldwide.

- ^ The Roman Curia is a "bureaucracy that assists the pope in his responsibilities of governing the universal Church. Although early in the history of the Church bishops of Rome had assistants to help them in the exercise of their ministry, it was not until 1588 that formal organization of the Roman Curia was accomplished by Pope Sixtus V. The most recent reorganization of the Curia was completed in 1988 by Pope John Paul II in his apostolic constitution Pastor Bonus".[161] The Curia functioned as the civil government of the Papal States until 1870.[162]

- ^ The 73-book Catholic Bible contains the Deuterocanonicals, books not in the modern Hebrew Bible and not upheld as canonical by most Protestants.[251] The process of determining which books were to be considered part of the canon took many centuries and was not finally resolved in the Catholic Church until the Council of Trent.

- ^ The Tridentine Mass was the ordinary form of the Roman-Rite Mass standardized by Pope Pius V after the Council of Trent in the 16th century; although it was superseded in 1969 by the Roman Missal of Paul VI; it continues to be offered according to that of 1962, as authorised by the documents Quattuor Abhinc Annos (1984), Ecclesia Dei (1988)[278] and Summorum Pontificum (2007).

- ^ In 1980, Pope John Paul II issued a Pastoral Provision which allows members of the Episcopal Church (the U.S. branch of the worldwide Anglican Communion) to retain many aspects of Anglican liturgical rites as a variation of the Roman rite when they join the Catholic Church. Such "Anglican Use" parishes exist only in the United States

- ^ There is no official list of popes, but the Annuario Pontificio, published every year by the Vatican, contains a list that is generally considered to be the most authoritative.[citation needed] The Annuario Pontificio lists Benedict XVI, the current pope as of this writing, as the 265th pope of Rome. In 2001, a study was made by the Catholic Church into the history of the papacy.[286] Based on that research, in 2008 there have been 265 Popes and 267 pontificates.

- ^ A bishop can be one who holds the position of pope, cardinal (normally), patriarch, primate, archbishop, or metropolitan, as well, as ordinary diocesan bishop, auxiliary bishop or titular bishop.

- ^ Based on the Christ's example and his teaching as given in Matthew 19:11–12 and to St. Paul, who wrote of the advantages celibacy allowed a man in serving the Lord,[303] celibacy was "held in high esteem" from the Church's beginnings. It is considered a kind of spiritual marriage with Christ, a concept further popularized by the early Christian theologian Origen. Clerical celibacy began to be demanded in the 4th century, including papal decretals beginning with Pope Siricius.[304] In the 11th century, mandatory celibacy was enforced as part of efforts to reform the medieval church.[305]

References

- ^ "Concise Oxford English Dictionary" (online version). Oxford University Press. 2005. Retrieved 10 April 2009.

- ^ Marthaler, Berard (1993). The Creed. Twenty-Third Publications. p. 303. Retrieved 9 May 2008.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - ^ a b McBrien, Richard (2008). The Church. Harper Collins. p. xvii. Online version available here. Quote: The use of the adjective "Catholic" as a modifier of "Church" became divisive only after the East-West Schism ... and the Protestant Reformation ... In the former case, the West claimed for itself the title Catholic Church, while the East appropriated the name Holy Orthodox Church. In the latter case, those in communion with the Bishop of Rome retained the adjective "Catholic", while the churches that broke with the Papacy were called Protestant.

- ^ Libreria Editrice Vaticana (2003). "Catechism of the Catholic Church." Retrieved on: 2009-05-01.

- ^ The Vatican. Documents of the II Vatican Council. Retrieved on: 2009-05-04. Note: The Pope's signature appears in the Latin version.

- ^ Declaration on Christian Formation, published by National Catholic Welfare Conference, Washington DC 1965, page 13

- ^ Whitehead, Kenneth (1996). ""How Did the Catholic Church Get Her Name?" Eternal Word Television Network. Retrieved on 9 May 2008.

- ^ Example: 1977 Agreement with Archbishop Donald Coggan of Canterbury

- ^ Walsh, Michael (2005). Roman Catholicism. Routledge. p. 19. Online version available here

- ^ Beal, John (2002). New Commentary on the Code of Canon Law. Paulist Press. Retrieved 13 May 2008.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) p. 468 - ^ The New Catholic Encyclopedia states: "There is a further aspect of the term Roman Catholic that needs consideration. The Roman Church can be used to refer, not to the Church universal insofar as it possesses a primate who is bishop of Rome, but to the local Church of Rome, which has the privilege of its bishop being also the primate of the whole Church."

- ^ a b "Number of Catholics and Priests Rises". Zenit News Agency. 12 February 2007. Retrieved 21 February 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - ^ a b "CIA World Factbook". United States Government Central Intelligence Agency. 2009. Retrieved 23 September 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - ^ "Major Branches of Religions Ranked by Number of Adherents". adherents.com. Retrieved 2009-07-05.

- ^ a b "Factfile: Roman Catholics around the world". BBC News. 1 April 2005. Retrieved 24 March 2008.

- ^ Schreck, pp. 158–159.

- ^ a b Paul VI, Pope (1964). "Lumen Gentium chapter 3, section 22". Vatican. Retrieved 9 March 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - ^ Code of Canon Law, canons 331 and 336

- ^ Teaching with Authority, by Richard R. Gaillardetz, p. 57

- ^ a b Schreck, p. 153.

- ^ Barry, pp. 50–51.

- ^ Paragraphs number 857-859 (1994). "Catechism of the Catholic Church". Libreria Editrice Vaticana. Retrieved 25 October 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Paragraphs number 551-553 (1994). "Catechism of the Catholic Church". Libreria Editrice Vaticana. Retrieved 25 October 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Paragraphs number 860-862 (1994). "Catechism of the Catholic Church". Libreria Editrice Vaticana. Retrieved 25 October 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Paragraph number 1562 (1994). "Catechism of the Catholic Church". Libreria Editrice Vaticana. Retrieved 25 October 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Paragraphs number 880-882 (1994). "Catechism of the Catholic Church". Libreria Editrice Vaticana. Retrieved 25 October 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Schreck, p. 152.

- ^ Barry, p. 37, pp. 43–44.

- ^ a b Matthew 16:18–19

- ^ John 16:12–13

- ^ a b Marthaler, preface

- ^ O'Collins, p. v (preface).

- ^ Orlandis, preface

- ^ Vatican Council, Second (1964). "Lumen Gentium paragraph 14". Vatican. Retrieved 17 December 2008.

- ^ Paragraph number 846 (1994). "Catechism of the Catholic Church". Libreria Editrice Vaticana. Retrieved 27 December 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Paragraph number 819 (1994). "Catechism of the Catholic Church". Libreria Editrice Vaticana. Retrieved 16 May 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Kreeft, pp. 110–112.

- ^ a b Kreeft, p. 98, quote "The fundamental reason for being a Catholic is the historical fact that the Catholic Church was founded by Christ, was God's invention, not man's ... As the Father gave authority to Christ (Jn 5:22; Mt 28:18–20), Christ passed it on to his apostles (Lk 10:16), and they passed it on to the successors they appointed as bishops."

- ^ a b c Paul VI, Pope (1964). "Lumen Gentium". Libreria Editrice Vaticana. Retrieved 19 November 2009.

- ^ Vatican Council I (1996). "Dogmatic Constitution Pastor aeternus on the Church of Christ". EWTN. Retrieved 24 November 2009.

- ^ First Vatican Council (18 July 1870). "Pastor aeternus". EWTN. Retrieved 20 November 2009.

- ^ Duffy, p. 1.

- ^ a b Barry, p. 46.

- ^ a b Franzen pp. 17–18

- ^ a b Orlandis, p. 11 quote "But Jesus not only founded a religion – Christianity; he founded a Church. ... The Church was grounded on the Apostle Peter to whom Christ promised the primacy – 'and on this rock I will build my Church (Mt 16:18)'".

- ^ Eberhardt, p. 60

- ^ Vidmar, pp. 39-40

- ^ Kung, pp. 4–5

- ^ Bokenkotter, p. 30

- ^ Kelly, p. 6.

- ^ Duffy, paperback edition p. 13, quote "There is no sure way to settle on a date by which the office of ruling bishop had emerged in Rome, and so to name the first Pope, but the process was certainly complete by the time of Anicetus in the mid-150s, when Polycarp, the aged Bishop of Smyrna, visited Rome, and he and Anicetus debated amicably the question of the date of Easter."

- ^ Bokenkotter, p. 18, quote: "The story of how this tiny community of believers spread to many cities of the Roman Empire within less than a century is indeed a remarkable chapter in the history of humanity."

- ^ Wilken, p. 281, quote: "By the year 100, more than 40 Christian communities existed in cities around the Mediterranean, including two in North Africa, at Alexandria and Cyrene, and several in Italy."

- ^ a b "Rome (early Christian)." Cross, F. L., ed. The Oxford dictionary of the Christian church. New York: Oxford University Press. 2005

- ^ White (2004). Pg 127.

- ^ Ehrman (2005). Pg 187.

- ^ McGrath (2006). Pp 174–175.

- ^ a b Stark, Rodney (2003-07-01). "The Truth About the Catholic Church and Slavery". Christianity Today.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Wilken, p. 282.

- ^ Collins, p. 53–55.

- ^ Chadwick, Henry p. 361

- ^ Vidmar, pp. 40–42

- ^ Davidson, p. 169, p. 181.

- ^ Norman, pp. 27–28

- ^ a b Chadwick, Henry p. 371. Cite error: The named reference "McManners371" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Davidson, p. 155.

- ^ Barker, p. 846.

- ^ Schatz, pp. 9–20.

- ^ http://philtar.ucsm.ac.uk/encyclopedia/christ/early/donat.html

- ^ "Donatism." Cross, F. L., ed. The Oxford dictionary of the Christian church. New York: Oxford University Press. 2005

- ^ Davidson, p. 341.

- ^ Wilken, p. 286.

- ^ M'Clintock and Strong's Cyclopedia, Volume 7, page 45a.

- ^ Herring, p. 60.

- ^ Wilken, p. 283

- ^ Collins, pp. 61–62.

- ^ Duffy, p. 35.

- ^ Bokenkotter, p. 84–93.

- ^ Noble, p. 214.

- ^ a b Bokenkotter, pp. 35–36. Cite error: The named reference "Bokenkotter223" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Le Goff, pp. 5–20.

- ^ a b Le Goff, p. 21.

- ^ Woods, p. 27.

- ^ Le Goff, p. 120.

- ^ Duffy, pp. 50–52.

- ^ a b Mayr-Harting, pp. 92–94.

- ^ a b Vidmar, pp. 82–83, quote: "How it [monasticism] came to Ireland is a matter of some debate. The liturgical and literary evidence is strong that it came directly from Egypt without the moderating influence of the Roman Church."

- ^ Johnson, p. 18.

- ^ a b Johns, p. 166 Cite error: The named reference "McManners187" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Vidmar, p. 94.

- ^ a b Vidmar, pp. 102–103.

- ^ a b Duffy, p. 63, p. 74.

- ^ Vidmar, pp. 107–111.

- ^ Duffy, p. 78.

- ^ Duffy, pp. 81–82.

- ^ Duffy, p. 91.

- ^ Collins, p. 103.

- ^ Vidmar, p. 104

- ^ Duffy, p. 119, p. 131.

- ^ a b Bokenkotter, pp. 140–141.

- ^ Duffy, pp. 88–89.

- ^ Woods, pp. 40–44.

- ^ Le Goff, pp. 80–82.

- ^ Le Goff, p. 225.

- ^ Bokenkotter, pp. 116–120.

- ^ Noble, pp. 286–287.

- ^ Riley-Smith, p. 8.

- ^ Vidmar, pp. 130–131.

- ^ Le Goff, pp. 65–67.

- ^ Tyerman, pp. 525–560.

- ^ "Pope sorrow over Constantinople". BBC News. 29 June 2004. Retrieved 6 April 2008.

- ^ a b Norman, pp. 62–65.

- ^ a b Norman, p. 93.

- ^ Le Goff, p. 87.

- ^ Woods, pp. 44–48.

- ^ Bokenkotter, pp. 158–159.

- ^ Henry Charles Lea, 'A History of the Inquisition of the Middle Ages', Volume 1, (1888), p. 145, quote: "The murder of the legate Pierre de Castelnau sent a thrill of horror throughout Christendom...Of its details, however, the accounts are so contradictory that it is impossible to speak of it with precision."

- ^ a b Morris, p. 214

- ^ Vidmar, pp. 144–147, quote: "The Albigensian Crusade, as it became known, lasted until 1219. The pope, Innocent III, was a lawyer and saw both how easily the crusade had gotten out of hand and how it could be mitigated. He encouraged local rulers to adopt anti-heretic legislation and bring people to trial. By 1231 a papal inquisition began, and the friars were given charge of investigating tribunals."

- ^ a b Bokenkotter, p. 132.

- ^ Black, pp. 200–202.

- ^ Kamen, p. 48–49.

- ^ a b Vidmar, pp. 150–152.

- ^ Kamen, p. 59, p. 203.

- ^ Kamen, p. 49

- ^ Norman, p. 93

- ^ Morris, p. 215, quote: "The inquisition has come to occupy such a role in European demonology that we must be careful to keep it in proportion. ... and the surviving records indicate that the proportion of executions was not high."

- ^ Vidmar, p. 146.

- ^ Peters, p. 112

- ^ Noble, p. 582, pp. 593–595.

- ^ Mason, Michael (18 August 2008). "How to Teach Science to the Pope". Discover Magazine. Retrieved 24 September 2008.

- ^ Duffy, p. 122.

- ^ Morris, p. 232.

- ^ Vidmar, p. 155.

- ^ a b Collinson, p. 240

- ^ Woods, pp. 115–27.

- ^ Duffy, p. 133.

- ^ Hall, p. 100.

- ^ a b Murray, p. 45.

- ^ Norman, p. 86.

- ^ a b Bokenkotter, pp. 201–205.

- ^ Duffy, p. 149.

- ^ a b Vidmar, p. 184.

- ^ a b Bokenkotter, p. 215.

- ^ Vidmar, pp. 196–200.

- ^ a b Vidmar, p. 233.

- ^ a b Bokenkotter, p. 233.

- ^ Duffy, pp. 177–178.

- ^ a b Bokenkotter, pp. 235–237.

- ^ Moyes, James (1913). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ Schama, pp. 309–311.

- ^ Vidmar, p. 220.

- ^ Noble, p. 519.

- ^ Vidmar, pp. 225–256.

- ^ Solt, p. 149

- ^ Judith F. Champ, 'Catholicism', in John Cannon (ed.), The Oxford Companion to British History, rev. ed. (Oxford: University Press, 2002), p. 176.

- ^ Norman, pp. 131–132.

- ^ a b Bokenkotter, pp. 242–244.

- ^ Norman, p. 81.

- ^ Vidmar, p. 237.

- ^ Lahey, p. 1125.

- ^ "Brief Overview of the Administrative History of the Holy See". University of Michigan. 5 July 2007. Retrieved 17 October 2008.

- ^ Norman, pp. 91–92.

- ^ Johnson, p. 87.

- ^ Bokenkotter, p. 251.

- ^ a b Duffy, pp. 188–191.

- ^ Koschorke, p. 13, p. 283.

- ^ Dussel, pp. 39,59.

- ^ Hastings (1994), p. 72.

- ^ a b Noble, pp. 450–451.

- ^ Woods, p. 135.

- ^ a b c Koschorke, p. 287.

- ^ Johansen, p. 109, p. 110, quote: "In the Americas, the Catholic priest Bartolomé de las Casas avidly encouraged enquiries into the Spanish conquest's many cruelties. Las Casas chronicled Spanish brutality against the Native peoples in excruciating detail."

- ^ Woods, p. 137.

- ^ Chadwick, Owen, p. 327.

- ^ Dussel, p. 45, pp. 52–53, quote: "The missionary Church opposed this state of affairs from the beginning, and nearly everything positive that was done for the benefit of the indigenous peoples resulted from the call and clamor of the missionaries. The fact remained, however, that widespread injustice was extremely difficult to uproot ... Even more important than Bartolomé de Las Casas was the Bishop of Nicaragua, Antonio de Valdeviso, who ultimately suffered martyrdom for his defense of the Indian."

- ^ Koschorke, p. 21.

- ^ Koschorke, p. 3, p. 17.

- ^ a b Koschorke, pp. 31–32.

- ^ McManners, p. 318.

- ^ McManners, p. 328.

- ^ Duffy, p. 193.

- ^ Bokenkotter, p. 295.

- ^ Norman, pp. 111–112.

- ^ a b Pollard, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Bokenkotter, pp. 283–285.

- ^ Collins, p. 176.

- ^ Bokenkotter, pp. 293–295

- ^ Duffy, pp. 214–216.

- ^ Duffy, p. 221.

- ^ Duffy, p. 240.

- ^ Leith, p. 143.

- ^ Duffy, p. 232.

- ^ Fahlbusch, p. 729.

- ^ Bokenkotter, pp. 306–307.

- ^ Bokenkotter, pp. 386–387.

- ^ Hastings, pp. 397–410.

- ^ a b Stacy, p. 139.

- ^ Bethell, Leslie (1984). The Cambridge history of Latin America. Cambridge University Press. pp. 528–529, 234. ISBN 0521232252.

- ^ Kirkwood, Burton (2000). History of Mexico. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group, Incorporated. pp. 101–192. ISBN 9781403962584.

- ^ Hamnett, Brian R (1999). Concise History of Mexico. Port Chester, NY: Cambridge University Pres. pp. 163–164. ISBN 0-521-58120.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: length (help) - ^ a b Chadwick, Owen, pp. 264–265.

- ^ Scheina, p. 33.

- ^ Van Hove, Brian (1994). "Blood Drenched Altars". EWTN Global Catholic Network. Retrieved 9 March 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - ^ Riasanovsky 617

- ^ Riasanovsky 634

- ^ Payne, Stanley G (2008). Franco and Hitler: Spain, Germany and World War II. Yale University Press. p. 13. ISBN 0300122829.

- ^ Fernandez-Alonso, J (2002). The New Catholic Encyclopedia. Catholic University Press/Thomas Gale. pp. 395–396. ISBN 0-7876-4017-4.

{{cite book}}: Text "volume 13" ignored (help) - ^ a b Coppa, p. 132-7

- ^ Rhodes, p. 182-183

- ^ Rhodes, p. 197

- ^ Shirer, p. 235.

- ^ a b McGonigle, p. 172

- ^ Bokenkotter, pp. 389–392

- ^ Rhodes, p. 204-205

- ^ Vidmar, p. 327

- ^ Cook, p. 983

- ^ Bokenkotter p. 192

- ^ a b Deák, p. 182.

- ^ Eakin, Emily (1 September 2001). "New Accusations Of a Vatican Role In Anti-Semitism; Battle Lines Were Drawn After Beatification of Pope Pius IX". The New York Times. Retrieved 9 March 2008.

- ^ Phayer, pp. 50–57

- ^ Bokenkotter, pp. 480–481

- ^ Dalin, p. 10

- ^ Randall, Gene (26 March 2000). "Pope Ends Pilgrimage to the Holy Land". CNN. Retrieved 9 June 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - ^ Smith, Craig (10 January 2007). "In Poland, New Wave of Charges Against Clerics". The New York Times. Retrieved 23 May 2008.

- ^ "Pope Stared Down Communism in Homeland – and Won". CBC News. April 2005. Retrieved 31 January 2008.

- ^ a b Bokenkotter, pp. 356–358.

- ^ a b Chadwick, Owen pp. 259–260.

- ^ "China installs Pope-backed bishop", BBC News 21 Sept 2007, retrieved 08 Sept 2009

- ^ a b Duffy, pp. 270–276.

- ^ Duffy, Saints and Sinners (1997), p. 274.

- ^ Ivereigh, Austen (21 October 2009). "Rome's new home for Anglicans". The Washington Post. Retrieved 7 December 2009.

- ^ "Roman Catholic–Eastern Orthodox Dialogue". Public Broadcasting Service. 14 July 2000. Retrieved 16 February 2008.

- ^ Bauckham, p. 373.

- ^ Paul VI, Pope (1968). "Humanae Vitae". Vatican. Retrieved 2 February 2008.

- ^ Bokenkotter, p. 27, p. 154, pp. 493–494.

- ^ Bruni, p. 336.

- ^ "Liberation Theology". BBC. Retrieved 12 September 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - ^ Rohter, Larry (7 May 2007). "As Pope Heads to Brazil, a Rival Theology Persists". The New York Times. Retrieved 21 February 2008.

- ^ Saul, Michael (10 July 2009). "President Obama, Pope Benedict XVI meet for first time in Rome". New York Daily News. Retrieved 28 February 2010.

- ^ "Pope Benedict XVI meets with Shimon Peres, then with Saudi FM". The Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 28 February 2010.

- ^ "Pope urges global unity on crises". BBC News. 19 April 2008. Retrieved 27 August 2008.

- ^ Kreeft, p. 17.

- ^ John Paul II, Pope (1997). "Laetamur Magnopere". Vatican. Retrieved 9 March 2008.

- ^ Schreck, p. 131.

- ^ Paragraph numbers 777–778 (1994). "Catechism of the Catholic Church". Libreria Editrice Vaticana. Retrieved 8 February 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Paul VI, Pope (1964). "Lumen Gentium chapter 2". Vatican. Retrieved 9 March 2008.

- ^ a b Schreck, pp. 146–147.

- ^ a b Schreck, pp. 15–19.

- ^ Brodd, Jefferey (2003). World Religions. Winona, MN: Saint Mary's Press. ISBN 978-0-88489-725-5.

- ^ a b Schreck, p. 21.

- ^ Schreck, p. 23.

- ^ Schreck, p. 30.

- ^ Paragraph number 1131 (1994). "Catechism of the Catholic Church". Libreria Editrice Vaticana. Retrieved 8 February 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Kreeft, pp. 298–299.

- ^ Mongoven, p. 68.

- ^ Schreck, p. 227.

- ^ a b Kreeft, pp. 71–72.

- ^ McGrath, pp. 4–6.

- ^ a b Paragraph numbers 1850, 1857 (1994). "Catechism of the Catholic Church". Libreria Editrice Vaticana. Retrieved 8 February 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Barry, p. 77.

- ^ Paragraph number 608 (1994). "Catechism of the Catholic Church". Libreria Editrice Vaticana. Retrieved 8 February 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Schreck, p. 113.