m additions. |

|||

| Line 678: | Line 678: | ||

==The Armenian Quarter== |

==The Armenian Quarter== |

||

[[File:Armenian quarter-Nicosia.jpg|thumb|right|Location of Nicosia's Armenian Quarter, shown in red. The light blue line |

[[File:Armenian quarter-Nicosia.jpg|thumb|right|Location of Nicosia's Armenian Quarter, shown in red. The light blue line divides the Arab Ahmed Pasha and the Karaman Zade quarters]] |

||

[[File:Tanzimat Street-1.jpg|thumb|right|View of Tanzimat street (1950s)]] |

[[File:Tanzimat Street-1.jpg|thumb|right|View of Tanzimat street (1950s)]] |

||

[[File: |

[[File:Andar - 1946.jpg|thumb|Excursion of the Armenian kindergarten on Roccas bastion (1946)]] |

||

[[File:Victoria street-Nicosia.jpg|thumb|right|Various parts of Victoria street (from the south to the north)]] |

|||

[[File:Tanzimat street-1.jpg|thumb|left|A bilingual sign of Tanzimat street]] |

[[File:Tanzimat street-1.jpg|thumb|left|A bilingual sign of Tanzimat street]] |

||

[[File:The innocent Armenians' drama-1.jpg|thumb|right|PIO Press Release on the ousting of the Armenians from their quarter]] |

[[File:The innocent Armenians' drama-1.jpg|thumb|right|PIO Press Release on the ousting of the Armenians from their quarter]] |

||

There is some evidence suggesting that the original Armenian |

There is some evidence suggesting that the original Armenian quarter (13th - late 15th/early 16th century) was located in the eastern part of Frankish Nicosia and that Armenians acquired their new quarter within the 16th century. What we do know for certain is that, after the conquest of the city in 1570, the Ottomans renamed the extant Armenian quarter to “Karamanzade mahallesi” (literally: quarter of the son of Karaman), in honour of one of the Generals who took part in the [[Ottoman–Venetian War (1570–73)|conquest of Cyprus]] and came from [[Karaman Eyalet]]. |

||

Since the Mediaeval Era and until December 1963, the western part of walled Nicosia formed what was known as the '''Armenian Quarter''' ['''''Αρμενομαχαλλάς''''' (in [[Greek language|Greek]]), '''''Հայկական թաղ''''' (in [[Armenian language|Armenian]]) or '''''Ermeni mahallesi''''' (in [[Turkish language|Turkish]])], which could be defined as follows: to the north of Paphos Gate, to the east of the moat, to the south of the fountain of Zahra street and to the west of the virtual line that formed the extension of Athanasios Diakos street towards Mula bastion. |

Since the Mediaeval Era and until December 1963, the western part of walled Nicosia formed what was known as the '''Armenian Quarter''' ['''''Αρμενομαχαλλάς''''' (in [[Greek language|Greek]]), '''''Հայկական թաղ''''' (in [[Armenian language|Armenian]]) or '''''Ermeni mahallesi''''' (in [[Turkish language|Turkish]])], which could be defined as follows: to the north of Paphos Gate, to the east of the moat, to the south of the fountain of Zahra street and to the west of the virtual line that formed the extension of Athanasios Diakos street towards Mula bastion. Administratively, the Armenian Quarter included both the Karaman Zade quarter and the Arab Ahmed Pasha quarter. |

||

After the British took over Cyprus, this part of the city housed several British officers. Their presence, together with that of the Latins (because of the existence of the Holy Cross cathedral and the [[Terra Santa College|Terra Santa school]], and later on Saint Joseph's school and convent), gave it the unofficial name “Φραγκομαχαλλάς” ([[Greek language|Greek]] for ''Levantine Quarter''), while it was in Victoria street that the first hotels of Nicosia opened (as opposed to the various existing inns), the “Armenian Hotel” (c. 1875- c. 1925) and the “Army and Navy Hotel” (1878 - c. 1890). Therefore, the first cutting in the [[Venetian walls of Nicosia|Venetian walls]] was made at the end of Victoria street at Paphos Gate in 1879. Similarly, not very far from there, the Anglicans built their cathedral, dedicated to Saint Paul, in 1885. FInally, for a period of time, in Victoria street were the “Nicosia Club” - also known as “English Club” - (1884-1896), the Catholic “Concordia Club” (1903-1954), as well as the [[Cyprus Museum]] (1889-1909). |

|||

Traditionally, the Armenian Quarter had the |

Traditionally, the Armenian Quarter had the largest concentration of Armenians in Nicosia, as it encompassed the Armenian compound ([[Notre Dame de Tyre|Virgin Mary]] church, Armenian Prelature of Cyprus, Melikian-Ouzounian School and Armenian Genocide monument), the club houses for the Armenian Club, the [[AGBU]] and [[AYMA, Nicosia|AYMA]], as well as a large number of Armenian homes and shops. On top of Roccas bastion there was a small forest (in [[Armenian language|Armenian]]: անտառ), which was a place of recreation for the area. |

||

Although the majority of its residents were Armenian-Cypriots, the Armenian Quarter was far from “monochrome”, as many [[Turkish Cypriots|Turkish-Cypriots]], as well as some [[Greek-Cypriots]], [[Maronites in Cyprus|Maronite-Cypriots]], [[Roman Catholicism in Cyprus|Latin-Cypriots]] and British used to live there. In fact, until the first years of the British Era, the area was also known as the Latin Quarter; later on it was split between the Karaman Zade and Arab Ahmed quarters. However, as the majority of residents were Armenian-Cypriots, as of 1927 the [[Muhtar (title)| |

Although the majority of its residents were Armenian-Cypriots, the Armenian Quarter was far from “monochrome”, as many [[Turkish Cypriots|Turkish-Cypriots]], as well as some [[Greek-Cypriots]], [[Maronites in Cyprus|Maronite-Cypriots]], [[Roman Catholicism in Cyprus|Latin-Cypriots]] and British used to live there. In fact, until the first years of the British Era, the area was also known as the Latin Quarter; later on, it was split between the Karaman Zade and Arab Ahmed Pasha quarters. However, as the majority of residents were Armenian-Cypriots, as of 1927 the [[Muhtar (title)|mukhtars]] of Karaman Zade quarter have been Armenian-Cypriots: '''Melik Melikian''' (1927–1949), '''Kasbar Delyfer''' (1949–1956), '''Vahe Kouyoumdjian''' (1956–2009) and '''Mgo Kouyoumdjian''' (2011–today). |

||

The heart of the Armenian quarter was '''Victoria street''' ''''' |

The heart of the Armenian quarter was '''Victoria street''' ('''''Վիքթորիա փողոց/Οδός Βικτωρίας/Viktorya sokağı'''''), in which the Armenian compound was located, as well as many houses and, at a later time, the [[AGBU]] club house; at times, [[AYMA, Nicosia|AYMA]]'s club house was there as well. Victoria street was the road that every Armenian-Cypriot would walk on to go to church, to school, to the clubs, to visit family, relatives and friends etc. One could see all the time Armenian-Cypriots walking around the narrow streets amidst a profusion of Oriental smells and a chatter in Armenian. The street, full of beautiful [[ashlar]] buildings, started from the Latin church of the Holy Cross and ended at the [[Arabahmet Mosque|Arab Ahmed Pasha mosque]], having Mahmoud Pasha street as its extension (where the [[American Academy Nicosia]] was between 1922-1955 and the Armenian Evangelical church since 1946). As it was a one-way street, traffic was only allowed from the north to the south. |

||

The other main road of the Armenian Quarter was '''Tanzimat street''' ''''' |

The other main road of the Armenian Quarter was '''Tanzimat street''' ('''''Թանզիմաթ փողոց/Οδός Τανζιμάτ/Tanzimât sokağı'''''). As it was facing the moat (in [[Armenian language|Armenian]]: պարիսպ), football matches between Armenian-Cypriot and other teams would attract a large number of Armenian-Cypriot spectators on it. At a later stage, the [[AYMA, Nicosia|AYMA]] club house was located here. As this was also a one-way street, traffic was only allowed from the south to the north. Various byroads linked Tanzimat street to Victoria street. After the occupation of the area by the Turkish-Cypriot paramilitary organisations, even though Tanzimat street retained its name, Victoria street was illegally re-named into Şehit Salahi Şevket street. |

||

During the [[Cypriot intercommunal violence#1963 Turkish self-segregation|1963–1964 Turkish-Cypriot mutiny]], a large part of the Armenian Quarter of Nicosia was gradually taken over by Turkish-Cypriot extremists |

During the [[Cypriot intercommunal violence#1963 Turkish self-segregation|1963–1964 Turkish-Cypriot mutiny]], a large part of the Armenian Quarter of Nicosia was gradually taken over by Turkish-Cypriot extremists between 21 December 1963 and 19 January 1964. Ten days later, they pillaged the [[Notre Dame de Tyre|Virgin Mary]] church and held captives for a few hours the Prelate, Senior Archimandrite Yervant Apelian, the parish priest, der Vazken Sandrouni, the Chairman of the Administrative Council of the Armenian Ethnarchy, Vahram Toundjian (Tountayian), and deacon Hrant Mamigonian. |

||

Most Armenian-Cypriots left their houses out of fear and terror: some families fled for 2–3 days to the grounds of the Melikian-Ouzounian school and the church, until these places were also captured, while other families stayed for a longer period at the grounds of the [[Melkonian Educational Institute]]. Even though some returned, this was temporary, as on 4 March 1964 extremist Turkish-Cypriots drove them out of their houses, after presenting them with threatening ultimata in their post boxes. In total, 231 Armenian-Cypriot families became victims to the Turks. |

Most Armenian-Cypriots left their houses out of fear and terror: some families fled for 2–3 days to the grounds of the Melikian-Ouzounian school and the church, until these places were also captured, while other families stayed for a longer period in tents at the grounds of the [[Melkonian Educational Institute]]. Even though some returned, this was temporary, as on 4 March 1964 extremist Turkish-Cypriots drove them out of their houses, after presenting them with threatening ultimata in their post boxes. In total, 231 Armenian-Cypriot families became victims to the Turks. |

||

The loss of the Armenian Quarter had a significant impact on the cohesion of the Armenian community of Nicosia: even though, already since the 1950s, a growing number of Armenian-Cypriots resided outside the Armenian Quarter [mainly in [[Ayios Dhometios]] and the Keushklu Chiftlik (around the [[Ledra Palace Hotel|Ledra Palace hotel]]), Neapolis and Constantia areas], the once concentrated Armenian-speaking population in such a small distance from the church, the school and the clubs suddenly found itself scattered across Greek-speaking Nicosia, away from the aforementioned Armenian entities. |

|||

| ⚫ | Today the Armenian Quarter has changed completely |

||

| ⚫ | Today the Armenian Quarter has changed completely: most houses, if not all, are inhabited by illegal Turkish settlers from [[Anatolia]], just like the majority of Turkish-occupied walled city of Nicosia. Despite the rehabilitation of the area between 1987-1998 (by [[United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees|UNHCR]] and 1998-2004 (by [[United Nations Development Programme|UNDP]] and [[United Nations Office for Project Services|UNOPS]]), as part of the Nicosia Master Plan, the residents' neglect is obvious. The only things remaining to remind a visitor that the area used to be inhabited by Armenians in the past are the existence of the [[Notre Dame de Tyre|Armenian compound]] in Victoria street, which was extensively renovated between 2009-2012, the dedicatory inscription on the Armenian Evangelical church in Mahmoud Pasha street and a commemorative plaque on top of the entrance of the old Sinanian house on the corner of Tanzimat street and Dervish Pasha street. |

||

==The Armenian Legion== |

==The Armenian Legion== |

||

Revision as of 16:02, 6 September 2013

| Part of a series on |

| Armenians |

|---|

|

| Armenian culture |

| By country or region |

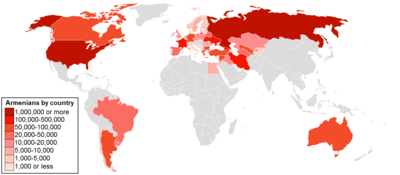

Armenian diaspora Russia |

| Subgroups |

| Religion |

| Languages and dialects |

|

| Persecution |

Armenians in Cyprus or Armenian-Cypriots (Armenian: Կիպրահայեր, Greek: Αρμενοκύπριοι, Turkish: Kıbrıs Ermenileri) are ethnic Armenians who live in Cyprus. The relation of Armenians with Cyprus and their presence on the island are very old and there has been a mutual economic and cultural association for many centuries. Armenians in Cyprus are a structured community with a long history and their presence has enriched the island in several ways; they are a recognised minority with their own language, schools, churches, cemeteries, monuments, information media, social institutions, customs, traditions and cultural life. During the last 50–60 years, the number of Armenians in Cyprus has decreased due to emigrations to other countries and integration into the broader Cypriot society, including intermarriage; their number today is smaller than it was 80 or 90 years ago. Economically, Armenian-Cypriots have tended to be self-employed businessmen/merchants, professionals or craftsmen.

Despite the relatively small number of Armenians living in Cyprus, the Armenian-Cypriot community has had a significant impact upon the Armenian Diaspora and the Armenian nation in general: during the Middle Ages, Cyprus had an extensive connection with the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia, while the Ganchvor monastery had an important presence in Famagusta; during the Ottoman Era, the Virgin Mary church and the Magaravank were very prominent. In more recent times, the short-lived National Educational Orphanage and the Melkonian Educational Institute were very influential, as was the presence of the Armenian Legion in Cyprus, while the emigration of a large number of Armenian-Cypriots to the United Kingdom virtually shaped today's British-Armenian community. Certain Armenian-Cypriots were or are very prominent on a Panarmenian or international level and the fact that, for nearly half a century, the survivors of the Armenian Genocide co-operated and co-existed peacefully with the Turkish-Cypriots, perhaps a unique phenomenon across the Armenian Diaspora. Additionally, the history and the various other aspects of the Armenian community of Cyprus are extremely well-documented. Finally, Cyprus was the first country to bring the issue of the Armenian Genocide recognition to the plenary session of the United Nations General Assembly in 1965 and the second country in the world to recognise the Armenian Genocide in 1975.

Currently, Armenians in Cyprus maintain a notable presence of about 3.500 on the island (including about 1.000 non-Cypriot Armenians, mainly from Armenia, Georgia, Lebanon, Russia and Syria),[1] mostly centred around the capital Nicosia, but also with communities in Larnaca and Limassol, where they have churches, schools, associations, cemeteries and monuments; there is also a small unstructured Armenian community in Paphos (virtually all of its members originate from Armenia).[2] The Armenian Prelature of Cyprus is located in Nicosia. According to the 1960 Constitution of Cyprus, together with the Maronites and the Latins, they are recognised as a “religious group” and have opted to belong to the Greek-Cypriot community. The Armenian-Cypriot community is strongly supported, financially and morally, by the Republic of Cyprus and Armenian-Cypriots are represented by an elected Representative in the House of Representatives; since May 2006, the Representative is Vartkes Mahdessian, a prominent businessman from Nicosia, who was re-elected in May 2011 for a new term in the House of Representatives.[3] The religious leader of the community, since August 1997, is Catholicosal Vicar Archbishop Varoujan Hergelian, accountable to the Catholicos of the Great House of Cilicia.

History

Of the three religious groups, Armenians are the oldest in Cyprus, since the first confirmed presence of Armenians on the island goes back to 578 AD, during the reign of Byzantine Emperor Justin II, while Maronites and Latins appeared on the island in 686 and 1126, respectively.

Byzantine Era (578–1191)

There is a long link between the Armenians and Cyprus, possibly dating back to the 5th century BC. However, Armenians have had a continuous documented presence in Cyprus since 578 AD: according to historian Theophylact Simocatta, during his campaign against the Persian King Chosroes I, Byzantine General Maurice the Cappadocian captured 10,090 Armenians as prisoners in Arzanene (Aghdznik), of whom about 3,350 were deported to Cyprus.[4] Judging by the strategic position of the colonies they established (Armenokhori, Arminou, Kornokipos, Patriki, Platani, Spathariko and perhaps Mousere), it is very likely that these Armenians served Byzantium as mercenary soldiers and frontiersmen.

More Armenians arrived during the reign of Armenian-descended Emperor Heraclius (610–641) for political reasons (he attempted to bridge the differences between the Armenian Church and the Byzantine Church), during the pontificate of Catholicos Hovhannes Odznetsi (717–728) for commercial reasons and after the liberation of Cyprus from the Arab raids by patrician Niketas Chalkoutzes (965) for military reasons, when Armenian mercenaries were transferred to Cyprus to protect its political sovereignty. In the mid-Byzantine period, Armenian generals and governors served in Cyprus, like Alexios Mousele or Mousere (868–874), Basil Haigaz (958), Vahram (965), Elpidios Brachamios (1075–1085) and Leo Symbatikes (910–911), who undertook the construction of Saint Lazarus' basilica in Larnaca. It appears that Saint Lazarus' church had been an Armenian Apostolic church in the 10th century and was used by Armenian-Catholics during the Latin Era.

The numerous Armenians required an analogous spiritual pastorate, and so in 973 Catholicos Khatchig I established the Armenian Bishopric in Nicosia. Relations between Cyprus and the Armenians became more intense when the Kingdom of Cilicia was established. The Kingdom, on the coast of Cilicia, to the north of the island, was established at around 1080 AD by Armenian refugees who fled the Seljuk invasion to the north and remained an ally of Byzantium. Between 1136–1138, Byzantine Emperor John II Comnenus moved the entire population of the Armenian city of Tell Hamdun to Cyprus. After Isaac Comnenus’ wedding to the daughter of the Armenian prince Thoros II in 1185, Armenian nobles and warriors came with him to Cyprus, many of whom defended the island against Richard the Lionheart (May 1191), when he landed in Limassol in a conquering mood, and the Knights Templar (April 1192), who had purchased Cyprus from Richard and they governed with a particular cruelty. Eventually, the Templars returned the island to Richard, who in turn sold it to Guy de Lusignan.[5]

Latin Era (1191–1570)

After the purchase of Cyprus by titular Frankish King of Jerusalem Guy de Lusignan in 1192, in his attempt to establish a western-type feudal Kingdom, the latter sent emissaries to Europe, Cilicia and the Levant, resulting in a massive immigration of Armenians and other peoples from Western Europe, Cilicia and the Levant (mainly Franks, Latins and Maronites, as well as Copts, Ethiopians, Georgians, Jacobites, Jews, Melkites, Nestorians and others). To these numerous bourgeois, noblemen, knights and warriors, fiefs, manors, lands, offices and various privileges were bounteously granted. Because of their proximity, their commercial ties and a series of royal and nobility marriages, the Kingdom of Cyprus and the Kingdom of Cilicia became inextricably linked. In the subsequent centuries, thousands of Cilician Armenians sought refuge in Cyprus fleeing the Muslim hordes and attacks: the Fall of Jerusalem (1267), the Fall of Acre (1291), the attack of the Saracens (1322), the Mameluke attacks (1335 and 1346) and the Ottoman occupation of Cilicia (1403 and 1421). Cyprus became now the easternmost bulwark of Christianity; in 1441 the authorities of Famagusta invited Armenians from Cilicia to settle there.

The Fall of Sis in April 1375 put an end to the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia; its last King, Levon V, was granted safe passage to Cyprus and died in exile in Paris in 1393, after calling in vain for another Crusade. In 1396, his title and privileges were transferred to his cousin, King James I de Lusignan, in the Saint Sophia cathedral; subsequently, the royal crest of the Lusignan dynasty also bore the lion of Armenia. Thus ended the last fully independent Armenian entity of the Middle Ages, after nearly three centuries of sovereignty and bloom; the title of "King of Armenia" was then held through the centuries down to the modern day by the House of Savoy, through the marriage of Queen Charlotte of Cyprus to Louis of Savoy. Although the Egyptian Mamelukes had taken over Cilicia, they were unable to maintain their hold on it; Turkic tribes eventually made their way to the region and established themselves there, leading to the conquest of Cilicia by Tamerlane. As a result, 30.000 Armenians left Cilicia in 1403 and settled in Cyprus, which continued to be ruled by the Lusignan dynasty until 1489.[6]

During the Frankish and the Venetian Eras (1192–1489 & 1489–1570, respectively), there were Armenian churches in Nicosia, Famagusta, Spathariko [Sourp Sarkis (Saint Sergius) and Sourp Varvare (Saint Barbara)], Kornokipos [Sourp Hreshdagabedk (Saint Archangels)], Platani [Sourp Kevork (Saint George)], Piscopia and elsewhere [Sourp Parsegh (Saint Basil)]. Armenians were amongst the seven most important religious groups in Cyprus, in possession of stores and shops in the ports of Famagusta, Limassol and Paphos, as well as in the capital Nicosia, thus controlling a large segment of commerce. Additionally, Armenian was one of the eleven official languages of the Kingdom of Cyprus and one of the five official languages of the Venetian colonial administration of Cyprus.

According to chroniclers Leontios Makhairas (1369–1458), George Boustronios (1430–1501) and Florio Bustron (1500–1570), the Armenians of Nicosia had their Prelature and used to live in their own quarter, called Armenia or Armenoyitonia. They originally had three churches: Sourp Kevork (Saint George), Sourp Boghos-Bedros (Saints Paul and Peter) and Sourp Khach (Holy Cross) - believed to the today's Arablar mosque or Stavros tou Missirikou. In Famagusta, a Bishopric was established in the late 12th century and Armenians lived around the Syrian quarter. Historical documents suggest the presence of an important monastic and theological centre there, at which Saint Nerses Lampronatsi (1153–1198) is said to have studied; of the three Armenian churches of walled Famagusta [Sourp Asdvadzadzin (Mother of God), Sourp Sarkis (Saint Sergius) and Sourp Khach (Holy Cross) - believed to be the unidentified church between the Carmelite church and Saint Anne], only Ganchvor church survives, built in 1346.

During the Middle Ages, Armenians in Cyprus were actively engaged in commerce, while some of them formed military garrisons in Kyrenia (1322) and elsewhere. A number of Armenians defended the Frankish Kingdom of Cyprus against the Genoese (1373) at Xeros, against the Saracens (1425) at Stylli village and against the Mamelukes (1426) in Limassol and Khirokitia. By 1425, the renowned Magaravank – originally the Coptic monastery of Saint Makarios near Halevga (Pentadhaktylos region) – came under Armenian possession, as did sometime before 1504 the Benedictine/Carthusian nunnery of Notre Dame de Tyre or Tortosa (Sourp Asdvadzadzin) in walled Nicosia; many of its nuns had been of Armenian origin (such as princess Fimie, daughter of the Armenian King Hayton II). During the Latin Era, there was also a small number of Armenian Catholics in Nicosia, Famagusta and the Bellapais Abbey, where Lord Hayton of Corycus served as a monk.

The prosperity of the inhabitants of Cyprus was brought to a halt by the harsh and corrupt Venetian administration and the iniquitous taxes they imposed. Their tyrannical rule, combined with adverse conditions (droughts, earthquakes, epidemics, famines, floods etc), caused a noticeable decline in the island's population. According to historian Stephen de Lusignan, by the late Venetian Era, Armenians lived mainly in Famagusta and Nicosia and, in small numbers, at three “Armenian villages”, Platani, Kornokipos and Spathariko.

Ottoman Era (1570–1878)

During the Osmanian conquest of the island (1570–1571), about 40.000 Ottoman-Armenian craftsmen were recruited (mainly sappers). The new order of things affected the Armenian community as well: many of the Ottoman Armenians who survived the conquest settled mainly in Nicosia, increasing its Armenian population, while the Armenian Prelature of Cyprus was recognised as an Ethnarchy (Ազգային Իշխանութիւն, Azkayin Ishkhanoutiun), via the millet institution. However, the Bishopric in Famagusta was abolished, as the Christian population was slaughtered or expelled and the entire walled city became forbidden for non-Muslims until the early years of the British Era. As a reward for their services during the conquest (whose exact nature we can only assume), the Armenians of Nicosia were granted the right to guard Paphos Gate (this privilege was used only for a short period, due to the large expenditure required) and, by a firman dated May 1571, they were given back the Notre Dame de Tyre church (also known as Tortosa), which the Ottomans had turned into a salt store. Additionally, the Magaravank monastery had won the favour of the Ottomans and became an important way station for Armenian and other pilgrims en route to the Holy Land, as well as a place of rest for travellers and Catholicoi and other clergymen from Cilicia and Jerusalem.

Contrary to the Latins and the Maronites, Armenians – being Orthodox – were not persecuted because of their religion by the Ottomans. Even though about 20.000 Armenians lived in Cyprus during the very first years of the Ottoman Era, by 1630 only 2.000 Armenians had remained (out of a total of 56.530 inhabitants). In the Bedestan (the covered market of Nicosia), there were many Armenian merchants and in the late 18th century/early 19th century Nicosia's leading citizen was an Armenian trader called Sarkis, who was a “beratli” (bearer of a privilege) and was initially the dragoman for the French Consul, before becoming the dragoman for the English Consul. Later on, in the early to mid-19th century, travellers and registers mention another rich Armenian merchant, Hadji Symeon Agha of Crimea, who had earlier financed a complete reparation of the Armenian Monastery and was Sarkis' son-in-law. A third Armenian notable was Mardiros Fugas, dragoman for the French Consul and a well-known trader, who was hanged in July 1821 by the Ottomans. Gifted with the acumen of industry, Armenians practised lucrative professions and in the beginning of the 17th century Persian Armenians settled in Cyprus as silk traders, as did some affluent Ottoman-Armenian families in the 18th and 19th centuries. However, with the new order of things, the number of Armenians and other Christians dramatically declined due to the onerous taxation and the harshness of the Ottoman administration, compelling many Christians to become Linobambaki (Crypto-Christians) or to embrace Islam, which explains why former Armenian villages (Armenokhori, Artemi, Ayios Iakovos, Ayios Khariton, Kornokipos, Melounda, Platani and Spathariko) were inhabited by “Turkish-Cypriots” at the end of the 19th century; a few Armenian-Cypriots became Catholics through marriage with affluent Latin families.

Gradually, after the bloody 1821 events – when, as a response to the Cypriot support to the Greek revolution, the Ottomans destroyed the Armenian and Greek mansions, prohibited Greeks, Franks, Armenians and Maronites to carry guns and hanged or massacred 470 notables, amongst them the Armenian parish priest of Nicosia, der Bedros -, some improvements were observed during the Tanzimat period (1839–1876). In the spirit of the Hatt-ı Şerif of Gülhane (1839), the Armenian Bishop, the Greek Archbishop and the Maronite Suffragan Bishop participated in the Administrative Council (Meclis İdare), which was formed in 1840. After 1850, some Armenians were employed in the civil service, while in 1860 the Armenian church of Nicosia became amongst the first in Cyprus to have a working belfry – donated by Constantinopolitan Armenian Hapetig Nevrouzian. Additionally, the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 benefited the Armenian and other merchants of the island, while in 1870 the first Armenian school was established in Nicosia by newly-arrived Archimandrite Vartan Mamigonian. Furthermore, as a result of the Hatt-ı Hümayun in 1856, the administrative autonomy of the Armenian Prelature of Cyprus was officially recognised.

Throughout the Ottoman Era (1571–1878), the vast majority of the Armenian population of Cyprus had been Armenian Orthodox, although there is also mention of a small Armenian Catholic community in Larnaca. Of the three religious groups, the Armenians are the only ones to have a continuous presence of Prelates throughout the Osmanian occupation. Based on various estimates, the Armenian-Cypriot community of the 19th century numbered between 150–250 persons, the majority of whom lived in Nicosia, with smaller numbers living in Famagusta, Larnaca, the north and south of the capital (especially in Dheftera and Kythrea) and, naturally, around the Magaravank.[5]

British Era (1878–1960)

With the arrival of the British in July 1878 and their progressive administration, the already prosperous yet small Armenian community of the island was particularly strengthened. Known for their linguistic skills, several Armenians were contracted to Cyprus to work as interpreters and public servants at the consulates and the British administration, such as Apisoghom Utidjian – the official state translator and interpreter for Ottoman Turkish between 1878 and 1919. The number of Armenians in Cyprus significantly increased following the massive deportations, the horrific massacres and the Genocide perpetrated by the Ottomans and the Young Turks (1894–1896, 1909 & 1915–1923). Cyprus widely opened its arms to welcome over 10.000 refugees from Cilicia, Smyrna and Constantinople, who arrived in Larnaca and all its other harbours, some by chance, others by intent; about 1.500 of them made the island their new home. Industrious, cultivated and progressive, they brought new life into the old community and did not need long to find their feet and establish themselves as people of the arts, letters and sciences, able entrepreneurs and formidable merchants, unsurpassed craftsmen and photographers, as well as pioneering professionals who introduced new crafts, dishes and sweets to the island, thus significantly contributing to Cyprus' socioeconomic and cultural development.[7]

The newcomers established associations, choirs, sports groups, Scout groups, bands, churches, schools and cemeteries in Nicosia, Larnaca, Limassol, Famagusta, Amiandos and elsewhere, while soon Armenophony became a reality. Armenians were the first locksmiths, mechanics, seat, comb and stamp makers, upholsterers, watchmakers and zincographers in Cyprus. They were the first to introduce the cinema, they significantly improved the craft of shoemaking and it was Armenians who first introduced Armenian bastourma, baklava, dried apricots, gassosa, gyros, halva, ice cubes, koubes, lahmadjoun, lokmadhes and pompes into the Cypriot cuisine – all very popular today. Armenians also introduced two techniques of embroidery needlework: the Aintab work (Այնթապի գործ) and the Marash work (Մարաշի գործ). There were also some Armenian factory owners (ice makers, soap makers, sock makers, tanners etc.), but above all, there was a disproportionately large number of Armenian photographers.

Law-abiding by nature, Armenian-Cypriots always had a high profile with the British administration and many became conscientious civil servants and disciplined policemen or were employed at the Cyprus Government Railway and at Cable and Wireless. Throughout the 1920s–1950s, many worked at the asbestos mines at Amiandos and the copper mines at Mavrovouni and Skouriotissa, some of whom had been trade unionists. Some Armenian-Cypriots participated in the 1897 Greco-Turkish War, the two World Wars (1914–1918 – at the Cyprus Muleteers' Corps – & 1939–1945 – both at the Cyprus Regiment and the Cyprus Volunteer Force) and the EOKA liberation struggle (1955–1959). Also, the Eastern Legion (later called Armenian Legion) was formed and trained between December 1916 and May 1918 in Monarga village, near Boghazi, consisting of over 4.000 Diasporan Armenian volunteers who heroically fought against the Ottoman Empire. Some Armenian refugees arrived from Palestine (1947–1949) and Egypt (1956–1957).[6]

The Armenian-Cypriot community prospered throughout the British Era (1878–1960), by establishing associations, choirs, Scout groups, sports teams, musical ensembles, churches, cemeteries and schools, including the renowned Melkonian Educational Institute. In many ways unique across the whole Armenian Diaspora, it was built just outside Nicosia between 1924–1926, after the generous and benevolent donation of the Egyptian-Armenian tobacco trading brothers Krikor and Garabed Melkonian, initially in order to shelter and educate 500 orphans of the Genocide, who planted the trees in front of the school in memory of their slaughtered relatives. From an orphanage (1926–1940), it gradually became a world-renowned secondary school with a boarding section (1934–2005).[8]

Examining the population censuses of the British Era (see Demography section), we observe a steady increase in the number of Armenians in Cyprus, ranging from 201 in 1881 to 4.549 in 1956. In their vast majority, they were Armenian Apostolic, but there was also a small number of Armenian Catholics and Armenian Protestants. In the 1960 population census, 3.628 Armenians were recorded – in contrast to 4.549 in 1956 – as about 900 Armenian-Cypriots had emigrated to Great Britain, Australia and elsewhere, not only because of the difficult economic conditions of the time, but mainly due to the emergency situation caused by the EOKA liberation struggle (1955–1959) and the uncertainty that some felt with the departure of the British, whom they viewed as their protectors. In fact, a large portion of British-Armenians hail from Cyprus.[6]

Independence Era (1960–present)

The end of the EOKA liberation struggle (1955-1959) found Armenian-Cypriots having forged strong bonds with the rest of the Cypriots. The 1960 Independence brought a new era for the Armenians of Cyprus, who – together with the Maronites and the Latins – were recognised as a “religious group” by the Constitution (Article 2 § 3) and were now represented by an elected Representative - initially a member of the Greek Communal Chamber (Article 109) and, since 1965, a member of the House of Representatives (Law 12/1965). The size of the community, however, had been reduced because of the emigration of about 900 Armenian-Cypriots to the United Kingdom, due to the emergency situation caused by the EOKA liberation struggle (1955–1959) and the poor state of the local economy. A second factor that contributed to the reduction of the community’s size was the emigration of about 600 Armenian-Cypriots to Soviet Armenia, as part of the Panarmenian movement for “repatriation” during the 1962–1964 period (nerkaght).[9]

During the 1963–1964 inter-communal troubles, the Armenian-Cypriot community suffered major losses, as the Armenian Quarter of Nicosia was captured by extremist Turkish-Cypriots: taken were the Prelature building, the mediaeval Virgin Mary church, the Melikian-Ouzounian school, the historical Genocide Monument, the club houses of the Armenian Club, AYMA and AGBU, as well as the Armenian Evangelical church; also taken was the mediaeval Ganchvor church in Famagusta. In total, 231 Armenian-Cypriot families became victims to the Turks and/or lost their shops and enterprises. As a result, hundreds of Armenian-Cypriots left for Great Britain, Canada, Australia and the United States.[7] After the 1974 Turkish invasion, the Armenian-Cypriot community suffered additional losses: 4–5 families living in Kyrenia, about 30 families in Nicosia and 40–45 families in Famagusta became refugees, while an Armenian-Cypriot lady (Rosa Bakalian) has been missing since then; the renowned Magaravank monastery in Pentadhaktylos was taken by the Turkish troops, the Melkonian boys' dormitory was bombed by the Turkish Air Force, while the Ayios Dhometios Armenian cemetery was hit by mortars and fell within the buffer zone. As a result, dozens of Armenian-Cypriots emigrated, mainly to Great Britain - in total, about 1.300 Armenian-Cypriots left Cyprus in the 1960s and 1970s, in addition to those who emigrated to Soviet Armenia.[5]

With the unfailing support of the government, the small yet industrious Armenian community of Cyprus gradually managed to recovered from its losses and continued to prosper in the remaining urban areas, contributing culturally and socioeconomically to the development of its homeland. On 24 April 1975, Cyprus became the first European country (and the second world-wide, after Uruguay) to recognise the Armenian Genocide with Resolution 36/1975; two more resolutions followed, Resolution 74/1982 and Resolution 103/1990, with the latter declaring 24 April as a National Remembrance Day of the Armenian Genocide in Cyprus. Over the past decades, the dynamics of the Armenian-Cypriot community have changed with the increased number of marriages with Greek-Cypriots and other non-Armenians, and the arrival over the last 30–35 years of thousands of Armenian political and economic immigrants because of the civil war in Lebanon (1975–1990), the insurgencies in Syria (1976–1982), the Islamic revolution in Iran and the Iran-Iraq war (1978–1988), as well as after the Spitak earthquake (1988) and the dissolution of the Soviet Union (1991); some of them have settled permanently in Cyprus. According to the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages of the Council of Europe, the Armenian language – the mother tongue of the vast majority of Armenian-Cypriots – was recognised as a minority language of Cyprus as of 1 December 2002. Today, it is estimated that Armenians living in Cyprus number over 3.500 persons; other than the countries mentioned above, in Cyprus there is also a small number of Armenians coming from Ethiopia, Greece, Kuwait, Turkey and the United Kingdom.[10]

Demography

There is no accurate information as to the number of Armenians living in Cyprus during the Byzantine Era. Although during the early Frankish Era there were tens of thousands of Armenians living in Cyprus (mainly in Nicosia and Famagusta - where in the latter they numbered around 1.500 souls in 1360), by the late Frankish Era and certainly during the Venetian Era, the number of Armenians in Cyprus dwindled - for a number of reasons: this was due to the tyrannical rule of the Venetian administration, combined with the adverse natural conditions (which affected all Cypriots), as well as the Hellenisation of the various minorities of the island. In fact, the 1572 survey of population and property of Nicosia after the Ottoman conquest, under beylerbey Sinan Pasha, recorded 90-95 local Armenians in Nicosia, out of about 1.100 inhabitants - all with completely Hellenised names.

It appears that during the very first years of the Ottoman Era (1570–1878), about 20.000 of the 40.000 recruited Ottoman Armenians had remained in Cyprus. Their number, however, rapidly declined, due to the harshness and the oppression of the regime, the onerous taxation and the natural disasters: according to the Latin Bishop of Paphos, Pietro Vespa, in 1630 there were only 2.000 Armenians in Cyprus (out of a total population of 56.350 - mostly living in rural areas), as a great number emigrated elsewhere and many others embraced Islam or they became Linobambaki (Crypto-Christians). Franciscan missionary Giovanni Battista da Todi recorded only 200 Armenians in Nicosia in 1647, while in 1660 he recorded over 300 Armenians on the island. Cardinal Bernardino Spada, representative of Propaganda Fide, also mentioned 200 Armenians in Nicosia in 1648, out of 3.000 inhabitants, also mentioning that their church was the largest in the capital, with 3 priests. Up until the mid-18th century, despite the limited arrival of Ottoman Armenians and Persian Armenians, their number was rather small. Russian monk Basil Barsky, who visited the island in 1727 and 1735, mentions “some Armenians” living in Nicosia. Visiting Cyprus in 1738, British traveler Richard Pococke mentions “very few Armenians, yet they have possession of an ancient church [in Nicosia]”, while for the island as a whole he makes mention to “a small number of Armenians, who are very poor, though they have an Archbishop and a convent in the country”. However, by the time Italian Abbot Giovanni Mariti visited Cyprus in 1760 and 1767, they had apparently become “the richest section of the inhabitants [of Nicosia]”, which is why thought “there are many Armenians [on the island]”. By the mid–19th century, following various waves of Hellenisation (peaceful assimilation) and Turkification (forced conversion), the number of Armenian-Cypriots ranged between 150–200.

When Englishman Captain John MacDonald Kinneir visited Cyprus in 1814, he estimated about 40 Armenian families in Nicosia (around 200 persons) - out of a total of 2.000 families (about 10.000 persons), as did British Consul Niven Kerr and Greek Vice-Consul Demetrios Margarites in 1844 and 1847, respectively. The first large-scale Ottoman census in 1831, under the supervision of Muhassil Halil Effendi, counted 114 non-Muslim males in the Armenian quarter of Nicosia and 13 at the Armenian Monastery (with a total male population of 45.365). Therefore, the number of Armenians in Cyprus would have been around 200 (out of a total of about 88.500). Visiting Cyprus in 1835, American missionary Rev. Lorenzo Warriner Pease writes “the number of Armenians [in Nicosia] is between 30 and 40 families”. In 1841, about 200 Armenians lived on the island (out of a total of 108.600), of whom about 150-160 resided in Nicosia (with a population of 12.000) - according to the record of population by Muhassil Talât Effendi and the writings of French historians and travellers Louis Lacroix and Count Louis de Mas Latrie. The Latin Vicar General Paolo Brunoni also mentioned 200 Armenians in Nicosia in 1848, as well as some others at the Magaravank. In 1874 Belgian traveler Edmond Paridant-van der Cammen estimated 190 Armenians in Nicosia (out of a total of 13.530). Although unreliable for the Armenian population of Nicosia (mentioning only 20 families in 1875), researcher Philippos Georgiou recorded 6-8 Armenian families around the Magaravank and 5 Armenian families in Larnaca. In 1877, newly-arrived priest Hovhannes Shahinian recorded 152 Armenians living in Cyprus, while the first modern population census of Nicosia, carried out in 1879 by the District Commissioner, Major-General Sir Robert Biddulph, counted 166 Armenians - out of a total of 11.197 inhabitants.

The British colonial censuses that took place between 1881 and 1956 provide us with fairly accurate data on the Armenian population of Cyprus. The following numbers are the combined figures of those recorded as Armenians (by religion) and those recorded as speakers of Armenian: in 1881 there were 201 Armenians in Cyprus (of whom 174 belonged to the “Armenian Church”), who increased to 291 in 1891 (of whom 269 were “Gregorians” and 11 “Armenian Catholics”) and to 553 in 1901 (of whom 491 were “Gregorians” and 26 “Armenian Catholics”); the numerical increase was due to the influx of Armenian refugees from the Hamidian massacres. In 1911 there were 611 Armenians in Cyprus (of whom 549 were “Gregorians” and 9 “Armenian Catholics”), while in 1921 their number rose to 1.573 (of whom 1.197 belonged to the “Armenian Church”) and to 3.617 in 1931 (of whom 3.377 were “Armenian Gregorians”), as a result of the huge wave of refugees from the Armenian Genocide.

In 1935 the Armenian Prelature recorded 3.819 Armenians in Cyprus: 102 were “native Cypriots” (mainly residing in Nicosia), 399 resided at the Melkonian Educational Institute, while 3.318 were “refugees”, i.e. Genocide survivors and their descendants; of those, 2.139 lived in Nicosia, 678 in Larnaca, 205 in Limassol, 105 in Famagusta, 58 in Amiandos, 25 in Lefka, 20 in Kalo Khorio (Lefka), 18 in Lefkara, 17 around the Magaravank, 5 in Kyrenia, 4 in Paphos and 44 in various villages. In 1946 there were 3.962 Armenians in Cyprus (of whom 3.686 were “Armenian Gregorians”), while in 1956 they numbered 4.549.[6] The table on the right shows the geographical distribution of Armenian-Cypriots per district from 1881 through 1960.

The last accurate census of the population of Cyprus with regard to its ethnic breakdown was carried out in 1960; it recorded 3.628 Armenians in Cyprus (of whom 3.378 were “Armenian Gregorians”). In 1978 and 1987 the Armenian Prelature recorded the Armenian population of Cyprus, which was 1.787 and 2.742, respectively (however, without extra information regarding their geographical distribution).

Since then, their number has increased; currently, about 3.500 Armenians live in Cyprus: 65% live in the capital, Nicosia, 20% in Larnaca, 10% in Limassol and 5% in Paphos and some villages. Over 95% of the Armenian population of Cyprus speak Armenian and are Armenian Orthodox (also known as Armenian Apostolic or Gregorian); some 5% belong either to the Armenian Evangelical Church, the Armenian Catholic Church, the Latin Church, the Greek Orthodox Church, the Anglican Church, the Plymouth Brethren Church, the Seventh-day Adventist Church or they are Jehovah's Witnesses. About 1.000 out of the 3.500 Armenians who live in Cyprus hail from Armenia, Lebanon, Syria, Russia, Georgia, Persia, Greece, Iraq, Ethiopia, Turkey and Kuwait. Most of the first wave of Armenians from Armenia who arrived in Cyprus from 1988 onwards were in fact the Armenian-Cypriots and their descendants who emigrated to Armenia between 1962–1964, as part of the nerkaght (ներգամթ – repatriation) Panarmenian movement.

The map on the right shows the places of origin of Armenian-Cypriots, based on a survey that Archbishop Bedros Saradjian conducted in 1935. According to available information, the about 1.000 refugees from the Hamidian massacres (1894–1896) mainly originated from Diyarbakir (Dikranagerd), Aintab and Kilis; only about 100 of them stayed. The next wave of Armenian refugees were the about 2.000 who fled the Adana massacre in 1909, most of whom returned to their ancestral homes in Adana within the same year.[11] However, the largest wave of Armenian refugees – some of whom had come before and returned – were the nearly 9.000 who escaped the massive deportations, the horrific massacres and the Genocide perpetrated by the Ottomans and the Young Turks; about 1.300 of them decided to stay, while the others eventually made arrangements to settle in other countries. Those refugees came mainly from Adana and Seleucia (Silifke), while there a significant number of them came from Sis, Marash, Tarsus, Caesarea, Hadjin and Aintab; smaller numbers came from other places, alphabetically: Adapazar, Adrianople (Edirne), Afion-Karahisar, Alexandretta (Iskenderoun), Arapgir, Armash, Baghche, Bardizag, Balian Dagh, Biredjik, Bitlis, Brusa, Chemishgezek, Constantinople (Bolis), Dörtyol, Edessa (Urfa), Erzerum, Eskishehir, Everek, Ikonion (Konya), Jeyhan, Kesab, Kharpert, Kutahia, Malatia, Mersin, Misis, Musa Dagh (Musa Ler), Nicomedia (Izmit), Rhaedestos (Tekirdagh), Sasun, Sebastia (Sivas), Shar, Sivri Hisar, Smyrna (Izmir), Tokat (Evdokia), Trepizond, Van, Yerzinga, Yozgat and Zeitun.[11]

Politics

Armenian-Cypriots have been politically organised since the late 19th century. The breakdown below examines their involvement in local administration, Cypriot politics and Armenian politics.

Local administration

With regard to local administration, the Armenian participation has been limited. Traditionally, there is the appointed mukhtar of Nicosia's Karaman Zade quarter (the Armenian Quarter). So far, there have been 4 mukhtars: Melik Melikian (1927–1949), Kasbar Delyfer (1949–1956), Vahe Kouyoumdjian (1956–2009) and Mgo Kouyoumdjian (2011–today). Bedros Amirayan served as an appointed member of Famagusta's municipal committee (1903–1905), Dr. Antranik L. Ashdjian served as an appointed municipal councillor and, later on, Vice Mayor, for Nicosia (1964–1970), while Berge Kevorkian served as an appointed municipal councillor for Nicosia (1970–1986).

Cypriot politics

With the exception of the elected Representatives, so far there has been only one Armenian-Cypriot MP in the House of Representatives, Marios Garoyian. He was elected as an MP for Nicosia District on 21 May 2006 with the Democratic Party and in October 2006 he became the party's President. After the election of Demetris Christofias as President of the Republic of Cyprus in February 2008, Marios Garoyian was voted Speaker of the House of Representatives on 6 March 2008, the second highest political position in Cyprus. He was re-elected as an MP for Nicosia District on 22 May 2011 and he served as House Speaker until 2 June 2011.

Armenian politics

Despite its relatively small size, the Armenian-Cypriot community has been an active participant in Panarmenian politics already since the late 19th century, even though this became more established in the mid-20th century. All three major Armenian Diaspora parties are active in Cyprus, especially ARF Dashnaktsoutiun. It established its presence in Cyprus as early as in 1897 and it continued to be present on and off on the island until the early years of the 20th century. At that time, Cyprus was frequently used as a stepping stone for some European Armenian fedayees who had Asia Minor and Cilicia as their final destination. However, after the Armenian Genocide, the party presence became minimal, save for individual members, supporters and/or sympathisers, until it was re-organised after World War II and was officially re-established in 1947; its chapter is called Karenian, after Armen Karo, who briefly visited Cyprus, in order to organise the assembly of weapons for the Zeitoun Resistance.

ARF Dashnaktsoutiun is affiliated with the Armenian Young Men's Association (AYMA) in Nicosia, the Armenian Club in Larnaca and the Limassol Armenian Young Men's Association (LHEM) in Limassol, as well as with the Armenian National Committee of Cyprus, the Armenian Youth Federation of Cyprus, the “Azadamard” Armenian Youth Centre, the Armenian Relief Society of Cyprus and the Hamazkayin Armenian Educational and Cultural Association of Cyprus, all based in Nicosia. The Armenian Relief Society chapter of Cyprus is called Sosse, after Sosse Mayrig, who visited Cyprus in the summer of 1938, while the Hamazkayin chapter of Cyprus is called Oshagan, after Hagop Oshagan, who had been a professor at the Melkonian Educational Institute between 1926–1934.

The ADL Ramgavar first appeared in Cyprus in the early 1930s, in the form of a core of party members. It also participated in the Diocesan Council elections of 1947, which caused a very big stir in community life. However, the party has officially been active in Cyprus since 1956. Its chapter is called Tekeyan, after Vahan Tekeyan, who had been a professor at the Melkonian Educational Institute between 1934–1935.[12] The party has never been very active on the island, mainly because it was overshadowed by the significant presence of the AGBU, affiliated with ADL Ramgavar. Both organisations lost a substantial number of followers, when they "repatriated" to Armenia between 1962–1964, as part of the nerkaght (ներգաղթ – repatriation) movement and when they realized that what was promised was not real.

The youngest Armenian political party in Cyprus is SDHP Hunchakian, which was set up on the island in 2005, following the split within the AGBU, which was brought about by the decision to close the Melkonian Educational Institute. It must be noted, though, that as Cyprus was frequently used as a stepping stone for some European Armenian fedayees who had Asia Minor and Cilicia as their final destination during the late 19th century and the early 20th century, a small number of the party's members temporarily stayed on the island during those times. SDHP Hunchakian is affiliated with the “Nor Serount” Cultural Association in Nicosia.

The Armenian-Cypriot community has been actively engaged in Panarmenian issues, such as the organisation of demonstrations and other forms of protest on matters that pertain to all Armenians. Other than promoting awareness and recognition of the Armenian Genocide, which is more extensively examined below, the Armenian-Cypriot community has been lobbying successfully in favour of the Nagorno-Karabakh Republic, as a result of which a Cypriot politicians and EuroMPs are sympathetic towards its existence. During the last decade, the Armenian-Cypriot community was actively involved in the movement to raise awareness on the unilateral closure of the Melkonian Educational Institute by the AGBU (2004–2005), the Armenia-Turkey protocols and the extradition of Ramil Safarov to Azerbaijan (2012), as well as in events commemorating Hrant Dink's memory, organised every year since his murder in 2007.

Finally, in recent years the Armenian-Cypriot community has been providing financial and humanitarian aid to Armenians in need around the world: it has provided assistance to earthquake-stricken Armenians in Armenia, after the 1988 earthquake, to orphans in Nagorno-Karabakh, to Armenians in Lebanon, Armenians in Greece and Armenians in Syria, as well as to Armenians in Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh, through the “Hayastan” All-Armenian Fund.

Armenian Genocide recognition

On the level of the ordinary people, most Cypriots are aware of the great calamity the Armenian nation suffered during 1894–1923 and have always been supportive and sympathetic towards Armenians; the Armenian Genocide refugees who remained in Cyprus were in the unique position of escaping from Ottoman Turks and living amicably amongst Turkish-Cypriots.

Cyprus has been one of the pioneering countries in recognising the Armenian Genocide, when on 25 January 1965 Foreign Minister Spyros Kyprianou first raised the issue to the General Assembly of the United Nations. Prior to his powerful speech, a delegation comprising ARF Dashnaktsoutiun Bureau members Dr. Papken Papazian and Berj Missirlian, as well as Armenian National Committee of Cyprus members Anania Mahdessian and Vartkes Sinanian, handed him a memorandum urging Cyprus' support in raising the issue at the United Nations.[13]

Cyprus was also the first European country (and the second world-wide, after Uruguay) to officially recognise the Armenian Genocide. On 24 April 1975, after the determined efforts and the submission by Representative Dr. Antranik L. Ashdjian, Resolution 36 was voted unanimously by the House of Representatives. Representative Aram Kalaydjian was instrumental in passing unanimously through the House of Representatives two more resolutions regarding the Armenian Genocide: Resolution 74/29–04–1982, submitted by the Foreign Relations' Parliamentary Committee, and Resolution 103/19–04–1990, submitted by all parliamentary parties. Resolution 103 declared 24 April as a National Remembrance Day of the Armenian Genocide in Cyprus.

Since 1965, when Cypriot government officials started participating in the annual Armenian Genocide functions, Cyprus' political leaders are often keynote speakers in those functions organised to commemorate the Armenian Genocide. Over the last years, there is usually a march starting from the centre of Nicosia and ending at the Virgin Mary church in Strovolos, where a commemorative event takes place in front of the Armenian Genocide Monument; other events also take place, such as blood donations.

Social life

The Armenian-Cypriot community has traditionally had an active and structured social life. Various charity, cultural, educational and social events are organised, such as fund-raisers/bazaars, art/book exhibitions, dancing/theatre performances, balls, lunches, film screenings, camps/excursions in Cyprus and abroad (panagoum), as well as lectures and commemoration ceremonies regarding Armenia, Nagorno-Karabakh, the Armenian Diaspora and the Armenian Genocide.

The main venue for community events is the AYMA club and the “Vahram Utidjian” Hall, at the basement of the Armenian Prelature building, both in Strovolos, Nicosia. In the past, numerous events were organised at the Melkonian Educational Institute in Aglandjia, the hall of the Armenian Club in Nicosia or the hall of the old AGBU club in Nicosia. School events take place at the open amphitheatre or the newly-built auditorium of Nicosia's Nareg Armenian School. More recently, some community events have been organised at the Larnaca Armenian Club or Limassol's Armenian church hall.

Originally, the Armenian church was a shack which was transferred in late 1959 from a British camp to the west of Nicosia, called Wayne's Keep, and was re-assembled by contractor Evagoras Constantinou. It was renovated in the early 1970s, under the care of George Didonian and had been used by the local AGBU chapter until 2002; it underwent radical restoration in 2009, with expenses by the Armenian Prelature of Cyprus and on 8 May 2010 it was inaugurated by Archbishop Varoujan Hergelian and Representative Vartkes Mahdessian. Since then, it is jointly used by the church, the local AGBU chapter and LHEM.

The “Vahram Utidjian” Hall (“Վահրամ Իւթիւճեան” Սրահ) took shape in 1998 by initiative of Archbishop Varoujan Hergelian, from the proceeds of the auction in 1994 of the art collection that antiques' collector Vahram Utidjian had donated to the Prelature in 1954. It was inaugurated on 3 February 1999 by Catholicos Aram I. Inside the Hall, there is a large painting by John Guevherian and Sebouh Abcarian, celebrating the 1700 years of Christianity in Armenia. On top of the shelter covering the entrance to the “Vahram Utidjian” Hall, there is a reddish tuff stone inscription in Armenian reading:

Իւթիւճեան Սրահ 1998 Utidjian Hall

Present organisations

Currently, the following Armenian clubs operate in Cyprus:

- AYMA [Armenian Young Men’s Association/Հայ Երիտասարդաց Միութիւն (Hay Yeridasartats Mioutiun)]. Established by a group of young Armenian men in Nicosia in October 1934, it is the leading Armenian-Cypriot club and the centre of the social, sports and cultural life of the Armenian-Cypriot community. After it was housed in various rented places, it acquired its own club house in 1961 in Tanzimat street, purchased for the sum of £6.000. As the club house was taken over during the 1963–1964 Turkish-Cypriot mutiny, AYMA became a victim to the Turks, as was the rest of the historical Armenian Quarter of Nicosia. It was then housed in various rented places. Its own premises, built between 1985–1986 by architects Marios & Nicos Santamas, are located at the corner of Alasia and Valtetsi streets, near the Virgin Mary church in Strovolos, Nicosia, on land leased by the government (Decision of the Council of Ministers 21.188/17–12–1981), and were inaugurated on 30 May 1987 by President Spyros Kyprianou. There is a well-organised library room at the club house. Its renovated and expanded functions hall was inaugurated on 28 February 2010 by Representative Vartkes Mahdessian. AYMA is affiliated with the Homenetmen Panarmenian organisation.

In front of AYMA's club house, there is a white marble tomb-ossuary containing some Armenian Genocide martyrs' remains brought to Cyprus by an Armenian Youth Federation mission from the Der Zor desert in Syria in 2001; it was constructed by members of the Armenian Youth Federation and was unveiled on 28 April 2002 by Archbishop Varoujan Hergelian.

To the left of the wall before the clubs entrance, there is a composition of tiles with AYMA's emblem bearing the following dedication in Armenian:

Յիշատակ Պետրոսեան ընտանիքի կողմէ 1991 (In memory of Bedrossian family 1991)

- AGBU [Armenian General Benevolent Union/Հայկական Բարեգործական Ընդհանուր Միութիւն (Haygagan Parekordzagan Enthanour Mioutiun)], with chapters in Nicosia (1913), Larnaca (1912) and Limassol (1936). The Nicosia AGBU acquired its own premises in 1957, when entrepreneur Movses Soultanian donated a 3-storey building in Victoria street. As the club house was taken over during the 1963–1964 Turkish-Cypriot mutiny, the Nicosia AGBU became a victim to the Turks, as was the rest of the historical Armenian Quarter of Nicosia. It was then housed in various rented places, until its club house was built between 1987–1988 by architects Iacovos & Andreas Philippou next to the Melkonian Educational Institute. The Larnaca AGBU is one of the oldest chapters in the world; as of 1972, it was housed in various rented places, until it built its own premises in 1975, located opposite the District Archaeological Museum. Between 2010–2011 a new club house was built by architect Meroujan Sarkissian. The Limassol chapter currently has no club house; as of 1959 and until 2002, it was housed at the Limassol Armenian church hall. There was also a chapter in Famagusta (1949–1974), with no club house. Both the Nicosia and the Larnaca AGBU have got big libraries and they are branches of the AGBU Panarmenian organisation. As of 1955, there is also AGBU's auxiliary body, the Women's Union [Տիկնանց Մարմին (Dignants Marmin)].

The Nicosia premises, in Limassol Avenue in Aglandjia, were inaugurated on 22 October 1989 by AGBU President Alec Manougian, while the new Larnaca premises, built between 2010–2011 in Kilkis street, were inaugurated on 5 May 2011 by President Demetris Christofias. To the side of the Nicosia club house, the sandstone bust of AGBU's founder Boghos Noubar Pasha was placed in 1991. Inside the Nicosia AGBU functions' hall, there is a white marble commemorative plaque in Armenian reading:

Ի յիշատակ Կարապետ եւ Եղիա Գըրպըյըքեաններու նուիրատուութեամբ Պօղոս Գըրպըյըքեանի Մարտ 1998 (In memory of Garabed and Yeghia Kerbeykian by donation of Boghos Kerbeykian March 1998)

Inside the Larnaca AGBU, there is a black granite commemorative plaque in Greek reading:

Η τελετή εγκαινίων του Αρμενικού Πολιτιστικού Κέντρου έγινε στις 5 Μαΐου 2011 από τον Εξοχότατο Πρόεδρο της Κυπριακής Δημοκρατίας κ. Δημήτρη Χριστόφια επί δημαρχίας Ανδρέα Μωϋσέως (The inaugural ceremony of the Armenian Cultural Centre took place on 5 May 2011 by His Excellency the President of the Republic of Cyprus Mr Demetris Christofias during the mayorship of Andreas Moyseos)

- Armenian Club [Հայ Ակումբ (Hay Agoump)], which was established in Larnaca in 1931. It has had an important contribution to Armenian cultural life in Larnaca. As of 2010, it is housed in rented premises at Holy Bishopric square, opposite the Prelature of Citium. It is affiliated with AYMA.

- LHEM [Limassol Armenian Young Men’s Association/Լիմասոլի Հայ Երիտասարդաց Միութիւն (Limasoli Hay Yeridasartats Mioutiun)]. Established in Limassol in 1996, Since 2001, it has no club house. It is affiliated with AYMA.

- “Nor Serount” Cultural Association [“Նոր Սերունդ” Մշակութային Միոեթիւն (“Nor Serount” Mshagoutayin Mioutiun)]. Established in Nicosia in 2005, it is housed in rented premises in Aglandjia Avenue since 2012. It is affiliated with the Homenmen Panarmenian organisation.

- Cypriot Armenian Progressive Movement [Կիպրահայ Յառաջդիմական Շարժում (Gibrahay Harachtimagan Sharjoum)]. It was established in Nicosia in 2010 and it is more like a movement than an association, with no club house.

The following associations operate within AYMA’s club house:

- Armenian National Committee of Cyprus [Կիպրոսի Հայ Դատի Յանձնախումբ (Gibrosi Hay Tadi Hantsnakhoump), 1965]. It provides general enlightenment regarding the Armenian Genocide and other matters regarding Armenia and the Armenian Diaspora.

- Armenian Youth Federation of Cyprus [Կիպրոսի Երիտասարդական Միութիւն (Gibrosi Yeridasartagan Mioutiun), 1977]. It edifies children, teenagers and young adults.

- “Azadamard” Armenian Youth Centre [Ազատամարտ Երիտասարդակամ Կեդրոն (Azadamard Yeridasartagan Getron), 1985]. It is responsible for the publication of the “Artsakank” newspaper.

- Armenian Relief Society of Cyprus [Հայ Օգնութեան Միութիւն (Hay Oknoutian Mioutiun), also known as HOM (ՀՕՄ), “Sosse” chapter, 1988]. It is a women's charity organization, which sends help to Armenia, Nagorno-Karabakh and the Armenian Diaspora.

- Hamazkayin Armenian Educational and Cultural Association of Cyprus [Համազգային Հայ Կրթական եւ Մշակութային Միութիւն (Hamazkayin Hay Grtagan yev Mshagoutayin Mioutiun), “Oshagan” chapter, 1999]. It organizes various cultural events, such as dance and theatre performances, art exhibitions, lectures etc.

AYMA used to have a widely-known football team (1945-2011), which between 2002-2011 played in the second category of the amateur league. It currently has a football academy (2011), a bowling team (2011) and a ping-pong academy (2012). AYF has the “Koyamard” (Գոյամարտ) youth group and the “Artsakh” (Արցախ) teenage group (both in 1977). Hamazkayin has the well-known “Sipan” dancing group (Սիփան: 2000), the “Timag” theatre company (Դիմակ: 2000) and the “Ardoudig” junior choir (Արտուտիկ: 2011); Sipan's annual dance performance has become very popular during the last years. The AGBU has the strong futsal team AGBU-Ararat (1999), which since 2002 has been leading the first league, as well as an U–17 team (2010) and an U–21 team (2011). The Nor Serount Cultural Association has got the Homenmen futsal team (2006), as of 2011 playing in the third league.

In Nicosia, there is also the Sourp Asdvadzadzin church choir (Սուրբ Աստւոածածին եկեղեցւոյ երգչախումբ: 1921), under the auspices of the Armenian Prelature of Cyprus, and the “Nanor” junior dancing group (Նանոր: 2008), under the auspices of the Office of the Armenian MP.

Finally, the following foundations operate within the Armenian-Cypriot community:

- Kalaydjian Foundation [Գալայճեան Հիմնարկոըթիւն (Kalaydjian Himnargoutiun), Larnaca: 1984].

- “Hayastan” All-Armenian Fund [“Հայաստան” Համահայկական Հիմնադրամ (“Hayastan” Hamahaygagan Himnatram), Nicosia: 1995].

- Pharos Arts Foundation [Ίδρυμα Τεχνών Φάρος (Idryma Technon Pharos), Nicosia: 1998].

- Arev Benevolent Foundation [Արեւ Բարեսիրական Հիմնարկութիւն (Arev Paresiragan Himnargoutiun), Nicosia: 2008].

The Kalaydjian Foundation manages the Kalaydjian Rest Home for the Elderly [Գալայճեան Հանգստեան Տուն (Kalaydjian Hankisdian Doun)] (Nicosia: 1988), which also houses Greek-Cypriot elderly. The Kalaydjian Rest Home for the Elderly was built on land leased by the government in Corinth street in Strovolos, Nicosia and it is one of the few purposely-built nursing homes in Cyprus. Its foundation stone was laid on 1 August 1987 by brothers Aram and Bedros Kalaydjian in memory of their parents, Roupen and Marie Kalaydjian, and its inauguration took place on 6 March 1988 by Minister of Interior Christodoulos Veniamin. The architects of the building were Athos Dikaios & Alkis Dikaios.

By initiative of the two brothers and in order to address the spiritual needs of its residents, on 15 December 1995 Catholicos Aram I laid the foundation stone for the Holy Saviour of All chapel; Catholicos Aram I consecrated the chapel on 16 February 1997. In 2005 the Rest Home underwent a major renovation and expansion with a second floor. The official inauguration of the new floor took place on 28 June 2006 by President Tassos Papadopoulos. The new floor is called “Alice and Arousiag Raphaelian” wing, after the sisters Arousiag and Alice Rafaelian, who bequeathed their house in Armenia street to the Kalaydjian Foundation.

The Kalaydjian Rest Home for the Elderly originally consisted of 12 rooms that surrounded a central courtyard. There was also a large dining area and a sitting room with a library. After the renovation, ten more rooms were added, as well as a large sitting room. The government contributed €170.000 to the project, against a total cost of about €700.000.

To the left outside the main entrance there is a black granite plaque reading:

Μέλαθρον Ευγηρίας Καλαϊτζιάν (in Greek) Գալայճեան Հանգստեան Տուն (in Armenian) Kalaydjian Rest Home (in English)

On the left of the lobby inside the main entrance there is another black granite commemorative plaque featuring a khachkar (cross-stone) and bearing the following inscription in Armenian:

Գալայճեան Հանգստեան Տուն ի յիշատակ Ռուբէն եւ Մարի Գալայճեաններու իրենց զաւակաց Պետրոսի եւ Արամի կողմէ – 1 օգոստոս (sic) 1987 (Kalaydjian Rest Home in memory of Roupen and Marie Kalaydjian by their children Bedros and Aram – 1 August 1987)

On the entrance to the second floor, under the framed photographs of Alice and Arousiag Raphaelian, there is the following plexiglas inscription:

Πτέρυγα Αρουσιάκ και Αλίς Ραφαελιάν (in Greek) Արուսեակ եւ Ալիս Ռաֆայէլեան Յարկաբաժին (in Armenian) Arousiag and Alice Raphaelian Wing (in English)

There is also the Middle East/Near East Armenian Research Centre, established in 1996 by Vartan Malian, located in Germanos Patron street, within the walled city of Nicosia, it houses a reference library and archival material in various languages. The Centre has undertaken the translation, in English and Greek, of books about the Armenian Genocide.

Previous organisations

From the various old, defunct clubs and associations, the following are notable:

- Armenian Club [Հայ Ակումբ (Hay Agoump), Nicosia: 1902–1963]. This club was established by local Armenian-Cypriots and was one of the oldest social clubs in Nicosia. It had a large library and functions' hall. As it became a victim to the Turks, its members mostly joined the AGBU club in Nicosia.

- Armenian Readers' Association [Հայ Ընթեռցասիրաց Միութիւն (Hay Entertsasirats Mioutiun), Nicosia: 1903–1963]. This was an auxiliary section of the Armenian Club.

- Armenian Women's Association [Հայուհեաց Միութիւն (Hayouhiats Mioutiun), Nicosia: 1916–1963]. This was an auxiliary section of the Armenian Club.

- Armenian Bibliophiles' Association [Հայ Գրասիրաց Միութիւն (Hay Krasirats Mioutiun), Larnaca: 1923–1931]. This association was established by Armenian Genocide refugees and was subsequently transformed into the Larnaca Armenian Club.

- Armenophony Association [Հայախօս Միութիւն (Hayakhos Mioutiun), Larnaca: 1923–1929]. This association was established by Manuel Kassouni, a teacher at the American Academy, in order to promote Armenophony amongst its students. Subsequently, its members joined the Armenian Bibliophiles' Association.

- Armenian Women's Association [Հայուհեաց Միութիւն (Hayouhiats Mioutiun), Larnaca: 1925–1931]. This was an auxiliary section of the Armenian Bibliophiles' Association.

- Armenian Ladies' Association [Հայ Տիկնանց Միութիւն (Hay Dignangts Mitouiun), Limassol: 1934–1951]. This club was dissolved due to the small number of members.

- Cilician Women's Association [Կիլիկիոյ Տիկնանց Միութիւն (Giligio Dignants Mioutiun), Nicosia: 1938–1949]. This association was established by a group of Armenian-Cypriot women and was subsequently transformed into the Hamazkayin Armenian Educational and Cultural Association, at the instigation of Peglar Navasartian.

- Friends of Armenian Association [Հայաստանի Բարեկամաց Միութիւն (Hayastani Paregamats Mioutiun), Nicosia, Larnaca, Limassol, Famagusta: 1944–1948]. This very active association was formed by AGBU supporters sympathetic to the cause of the nerkaght (ներգամթ – repatriation) movement. During the years it operated, it had its own sports teams, choir/band and newspapers, organising a variety of events. After it was decided that Cyprus would not be part of the nerkaght movement, the association died out and its members mostly joined the AGBU clubs in Nicosia, Larnaca, Limassol and Famagusta.

- Hamazkayin Armenian Educational and Cultural Association [Համազգային Հայ Կրթական եւ Մշակութային Միութիւն (Hamazkayin Hay Grtagan yev Mshagoutayin Mioutiun), Nicosia: 1949–1997]. This association, affiliated with AYMA, was dissolved because of internal disputes and was re-organised in 1999.

- New Armenian Club [Նոր Հայկական Ակումբ (Nor Haygagan Agoump), Larnaca: 1959–1972]. This club was formed by a group of AGBU supporters. Subsequently, it was absorbed by the Larnaca AGBU.

- “Azadamard” Youth Centre [“Ազատամարտ” Երիտասարդակամ Կեդրոն (“Azadamard” Yeridasartagan Getron), Nicosia: 1985–1997]. This association, which sprang off from AYMA, due to internal disputes, returned back to AYMA, as a distinct entity.

- “Stepan Shahoumian” Progressive Movement [“Ստեփան Շահումեան” Յառաջդիմական Շարժում (“Sdepan Shahoumian” Harachtimagan Sharjoum), Nicosia: 1994–2010]. This movement started at the instigation of Sergey Badalyan. Subsequently, it was transformed into the Cypriot Armenian Progressive Movement.

- Cyprus-Armenia Friendship Association [Σύνδεσμος Φιλίας Κύπρου-Αρμενίας (Syndesmos Philias Kyprou-Armenias), Nicosia: 1997–2006]. This association started at the instigation of Bedros Kalaydjian and its members were equally Armenian-Cypriots and Greek-Cypriots.

Until 1998, the Armenian Ethnarchy of Cyprus used to have the Armenian Charity Board [Հայ Աղքատախնամ Մարմին (Hay Aghkadakhnam Marmin)] in Nicosia and the Women's Charity Association [Տիկնանց Աղքատախնամ Միութիւն (Dignants Aghkadakhnam Mioutiun)] in Larnaca and Limassol.

Past and present fields of activity

Armenian-Cypriots have also been active in the following fields, especially in the past:

Music: The Melkonian Educational Institute was known for its choir and band, both founded by musician and composer Vahan Bedelian. Their recitals were often attended by the High Commissioner/Governor or the President; in later years, Sebouh Abcarian became its conductor. The Melikian-Ouzounian National School also had a band founded and conducted by Vahan Bedelian (1926–1941); in 1927, the exile “King of Arabia”, Shariff of Mecca Hussein bin Ali, purchased new musical instruments for it. In the mid–1940s, AYMA had the “Gomidas” church choir, founded and conducted by Sdepan Darakdjian, later archpriest Vazken Sandrouni. AYMA, AGBU and the Friends of Armenia Association (Paregamats) also had their amateur dance, choir and/or band ensembles. Other than Vahan Bedelian and Sebouh Abcarian, amongst well-known Armenian-Cypriot musicians were cellist Hayrabed Torossian (†) and violinist Ara Vorsganian, both veterans of the Cyprus Symphony Orchestra, violinist Manoug Parikian (†) (United Kingdom) and the violinists Haroutune Bedelian (California) and Levon Chilingirian (United Kingdom), as well as singers Hovig Demirjian and Gore Melian, and pianist and soprano Sona Gargaloyan (all in Nicosia).

Scouting: The Melkonian Educational Institute had the historical 7th Cyprus Scout Group (1931/1932–2006), established by Headmaster Krikor Giragossian, Chief Scouts Major Onnig Cowan and Hagop Palamoudian and professors Levon Apkarian, Kersam Aharonian, Parounag Tovmassian and Vahan Bedelian. AYMA had the 77th Cyprus Scout Group (1959–1974 and 1986–1990), established by AYMA's Chairman Anania Mahdessian and Chief Scouts Hagop Palamoudian and Artin Anmahouni. The Nicosia Armenian school had the 4th Cyprus Scout Group (1937–1963, 1966–1982 and 1996–2000), while the Larnaca Armenian school had the 11th Cyprus Scout Group (1938–1959 and 1997–2001). Previously, there were other Scout groups [e.g. Homenetmen Scouts, (Larnaca: 1920–1922 and Nicosia: 1925–1930)], the Larnaca Armenian school Scouts (1927–1930) and the 12th Cyprus Scout Group (Nicosia: 1936–1947), founded by Chief Scout Hagop Palamoudian. As most Scout groups were mixed, there were only two guide groups: 8th Cyprus Guide Group (Melikian-Ouzounian: 1949–1963) and 9th Cyprus Guide Group (Melkonian: 1950–2005). Three distinguished Armenian-Cypriot Scouts and Guides are worth special mention[why?]: Hagop Palamoudian, the first General Commissioner of the Cyprus Scouts Association (1960–1962); Takouhy Devledian, amongst the founders of the Girl Guides Association of Cyprus, served as its General Commissioner (1987–1990); Artin Anmahouni, currently the oldest active Scout in Cyprus, is as of 1965 Honorary Commissioner of Armenian Scouts in Cyprus.[citation needed]

Football: The Gaydzak (Կայծակ=Lightning) team (Nicosia: 1930–1931) became Cyprus’ first cup holder in 1931. AYMA’s football team (established in 1945 and suspended in 2011) was well-known amongst Cypriots, as it played in the first category (1947–1956 and 1960–1962); among its players were Armenian Archbishop of Greece, Sahag Ayvazian (†), and the former Speaker of the House of Representatives, Marios Garoyian. Other Armenian-Cypriot football teams were the ones of the Melkonian Educational Institute (1926–2005), of Homenetmen (1927–1928), Ararat (Արարատ) (1938–1940), Gaydzak (1943–1944 and 1960–1962, affiliated with the Armenian Club in Nicosia) and Nor Gaydzak (Նոր Կայծակ=New Gaydzak) (1944–1948, affiliated with the Friends of Armenia Association); after Nor Gaydzak stopped, some of its players found themselves in the first team of Omonia, such as Sarkis Bedigian (known by his nickname “Kilis”) and Dickran Missirian. A notable Armenian-Cypriot football coach was Aram Chaderdjian, who served as coach to Anorthosis and Nea Salamina.

Other sports: The Melkonian Educational Institute used to have volleyball and basketball teams (the latter won the first basketball championship in Cyprus, 1949–1950). The Friends of Armenia Association had a volleyball team. AYMA at times had ping-pong, darts, hockey and basketball teams; AYMA’s hockey team was established in 1945 and was for three consecutive years champion (1951–1954). The AGBU used to have women’s basketball and ping-pong teams. Of the various Armenian-Cypriot sportsmen in Cyprus, the most distinguished are rally driver Vahan Terzian (†), veteran tennis umpire Kevork Palandjian and tennis player Haig Ashdjian.