| Nahuatl, Mexicano, Nawatl | |

|---|---|

| Nāhuatlahtōlli, Māsēwallahtōlli | |

| Region | Mexico (Mexico (state), Distrito Federal, Puebla, Veracruz, Hidalgo, Guerrero, Morelos, Oaxaca, Michoacán and Durango) |

Native speakers | 1.7 million |

Uto-Aztecan

| |

| Official status | |

| Regulated by | Instituto Nacional de Lenguas Indígenas |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-2 | nah |

| ISO 639-3 | Variously:nci – Classical Nahuatlnhn – Central Nahuatlnch – Central Huasteca Nahuatlncx – Central Puebla Nahuatlnaz – Coatepec Nahuatlnln – Durango Nahuatlnhe – Eastern Huasteca Nahuatlngu – Guerrero Nahuatlazz – Highland Puebla Nahuatlnhq – Huaxcaleca Nahuatlnhk – Isthmus-Cosoleacaque Nahuatlnhx – Isthmus-Mecayapan Nahuatlnhp – Isthmus-Pajapan Nahuatlncl – Michoacán Nahuatlnhm – Morelos Nahuatlnhy – Northern Oaxaca Nahuatlncj – Northern Puebla Nahuatlnht – Ometepec Nahuatlnlv – Orizaba Nahuatlppl – Pipil languagenhz – Santa María la Alta Nahuatlnhs – Southeastern Puebla Nahuatlnhc – Tabasco Nahuatlnhv – Temascaltepec Nahuatlnhi – Tenango Nahuatlnhg – Tetelcingo Nahuatlnhj – Tlalitzlipa Nahuatlnuz – Tlamacazapa Nahuatlnhw – Western Huasteca Nahuatlxpo – Pochutec |

Nahuatl ([1]) is a group of related languages and dialects of the Aztecan[2] branch of the Uto-Aztecan language family which is indigenous to Mesoamerica and is spoken by around 1.5 million Nahua people in Central Mexico.

Groups speaking Nahuan languages have existed in central Mexico at least since 600 AD [3] and at the time of the Spanish conquest of Mexico one of these Nahuatl-speaking groups, the Aztecs dominated central Mexico. Because of the expansion of the Aztec Empire the dialect spoken by the Aztecs of Tenochtitlan had become a prestige language throughout Mesoamerica. With the arrival of the Spanish and the introduction of the Latin Alphabet Nahuatl became also a literary language with large amounts of chronicles, grammars, poetry, administrative documents and codices being written in the language during the 16th and 17th centuries[4]. This early literary language based on the Tenochtitlan dialect has been labelled Classical Nahuatl and is among the most studied and best documented languages of the Americas.

Today Nahuan dialects[5] are spoken by more than 1.5 million people in scattered villages, towns and rural areas[6], some of these dialects being mutually unintelligible. All of these dialects show influence from the Spanish language to various degrees, some of them much more than others. No modern dialects are identical with Classical Nahuatl, but those spoken in and around the Valley of Mexico are generally more closely related to it than are peripheral ones.[7]. Under the Mexican "Law of Linguistic Rights" Nahuatl is recognized as a "national language" with the same "validity" as Spanish and Mexico's other indigenous languages[8].

Nahuatl is a language with a complex morphology characterized by polysynthesis and agglutination, allowing the construction of long words with complex meaning out of several stems and affixes. Throughout the centuries of coexistence with the other Mesoamerican languages Nahuatl has been influenced by these and has become part of the Mesoamerican Linguistic Area.

Many words from Nahuatl have been borrowed into Spanish and further on into hundreds of other languages. These are mostly words for concepts indigenous to central Mexico which the Spanish heard mentioned for the first time by their Nahuatl names. English words of Nahuatl origin include "tomato" from Nahuatl tōmatl, "avocado" from Nahuatl ahuacatl, and "chili" from Nahuatl chīlli.

History

Precolumbian Period

Archaeological, historical and linguistic evidence suggest that the speakers of Nahuatl languages originally came from the northern Mexican deserts and migrated into central Mexico in several waves.[9] Before the Nahuan languages entered Mesoamerica they were probably spoken in northwestern Mexico alongside the Coracholan languages(Cora and Huichol).[10] The first group to split from the main group were the Pochutec who went on to settle on the Pacific coast of Oaxaca possibly as early as 400 AD[11] From ca 600 AD Nahuan speakers quickly rose to power in central Mexico and expanded into areas earlier occupied by speakers of Oto-Manguean, Totonacan and Huastec.[12]. Also some speakers of Nahuan moved south as far as El Salvador and Panama[13] becoming the ancestors of the speakers of modern Pipil.[14] The earliest migrations are thought to correspond to the modern peripheral dialects some of which are relatively conservative and do not display much influence from the central dialects.[15]

Around 1000 AD Nahuatl speakers were dominant in the Valley of Mexico and far beyond, and migrations kept coming in from the north. One of the last of these migrations to arrive in the valley settled on an island in the Lake Texcoco and proceded to subjugate the surrounding tribes. This group were the Mexica who during the next 300 years founded an empire based in Tenochtitlan their island capital. Their political and linguistic influence came to reach well into Central America and it is well documented that among several non-Nahuan ethnic groups, such as the K'iche' Maya, Nahuatl became a prestige language used for long distance trade and spoken by the elite groups.

Colonial Period

With the arrival of the Spanish in 1519 the tables turned for the Nahuatl language and a new language was now in the prestige position. But the missionary effort undertaken by monks from various monastic orders principally the Fransciscans, Dominicans and Jesuits introduced the alphabet to the Nahuas and they were eager to learn to read and write, both in Spanish and in their own language. Within the first ten years after the Spanish arrival texts were being prepared in the Nahuatl language written with Latin characters.

Also during this time institutions of learning were opened, such as the Colegio de Santa Cruz de Tlatelolco which was inaugurated in 1536 and which taught both indigenous and classical European languages to both Indians and priests. And missionary grammarians undertook the job of writing grammars for the indigenous languages in order to teach priests. For example the first grammar of Nahuatl, written by Andrés de Olmos, was published in 1547 - three years before the first grammar of French, and by 1645 another four grammars of Nahuatl had been published: One by Alonso de Molina in 1571, one by Antonio del Rincón in 1595, one by Diego de Guzman in 1642 and the grammar today seen as being the most important by Horacio Carochi in 1645.[16]

In 1570 Philip II of Spain decreed that Nahuatl should become the official language of the colonies of New Spain in order to facilitate communication between the Spanish and natives of the colonies.

During the 16th and 17th centuries Classical Nahuatl was used as a literary language and a large corpus of texts from that period is in existence today. Texts from this period include histories, chronicles, poetry, theatrical works, Christian canonical works, ethnographic description and all kinds of administrative and mundane documents. During this period the Spanish allowed for a great deal of autonomy in the local administration of indigenous towns and in many Nahuatl speaking towns Nahuatl was the de facto administrative language both in writing and speech. Among the most important works from this period is the Florentine Codex, a 12-volume compendium of Aztec culture compiled by Franciscan Bernardino de Sahagún; Crónica Mexicayotl, a chronicle of the royal lineage of Tenochtitlan by Fernando Alvarado Tezozomoc, Cantares Mexicanos a collection of songs in Nahuatl, the Nahuatl-Spanish/Spanish-Nahuatl dictionary compiled by Alonso de Molina and the Huei tlamahuiçoltica a description in Nahuatl of the apparition of the Virgin of Guadalupe.

Throughout the colonial period grammars and dictionaries of indigenous languages were composed, but strangely the quality of these were highest in the initial period and declined towards the ends of the 18th century[17]. In practice the friars found that learning all the indigenous languages was impossible and they began to focus on Nahuatl. During this period the linguistic situation of Mesoamerica was relatively stable. However, in 1696 Charles II made a counter decree banning the use of any languages other than Spanish throughout the Spanish Empire. And in 1770 a decree with the avowed purpose of eliminating the indigenous languages was put forth by the Royal Cedula[18]. This marked the end of Nahuatl as a literary language.

Modern Period

Throughout the modern period the situation for indigenous languages have become increasingly worse: Numbers of speakers for virtually all indigenous languages have decreased, and this is also the case for Nahuatl. Nahuatl is now mostly spoken in rural areas by the empoverished class of indigenous subsistence agriculturists. Since the early 20th century educational policies in Mexico have focused on "hispanification" of indigenous communities teaching only Spanish and discouraging the use of Nahuatl. Even so Nahuatl is spoken by well over a million people, most of whom are bilinguals but some of whom are monolingual, and Nahuatl is not as a whole endangered, even though some dialects are severely endangered and others have become extinct within the last ten years.

Geographic distribution

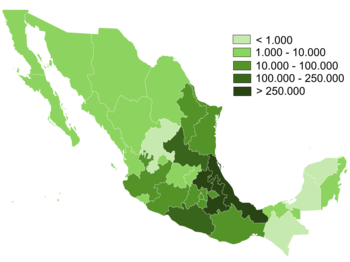

A range of Nahuatl dialects are currently spoken in an area stretching from the northern Mexican state of Durango to Veracruz in the south. Pipil[19], a Nahuatl dialect which happens to have its own name, is spoken as far south as El Salvador, by a small number of speakers[20]. Another Nahuan language, Pochutec, was spoken on the coast of Oaxaca until circa 1930[21].

The largest concentrations of Nahuatl speakers are found in the states of Puebla[22], Veracruz[23], Guerrero[24] and Hidalgo[25]. Significant populations are also found in México State, Morelos[26], and the Mexican Federal District. Smaller populations exist in Michoacán[27], and Durango[28]. In Jalisco and Colima the language has become extinct during the 20th century. Due to migrations within Mexico nahuatl groups of nahuatl speakers or even small language communities can be found in all of the Mexican states. Currently the influx of Mexican workers into the United States has created small Nahuatl-speaking communities in the United States, particularly in New York and California[29].

Classification and terminology

Terminology

The terminology relating to the Nahuatl varieties is rather vague and confusing - many terms are applied with differing meanings, or the some groupings have several names. Sometimes older terms are substituted with newer terms or the speakers own name for their specific variety.

The word Nahuatl itself is a Nahuatl word which is probably derived from the word "nāwatlahtolli" - "clear language". The language was formerly called "Aztec" because it was spoken by the Aztecs, who however didn't call themselves Aztecs but Mexica, and who called their language Mexicacopa[30]. Nowadays the term "Aztec" is rarely used for modern Nahuan languages, but the term "Aztecan" is used for the Nahuatl languages and dialects when described as the second constituent part of the Uto-Aztecan language family - this group is also often called "Nahuan". The term "General Aztec" is used by some linguists [31] to refer to the Aztecan languages but not Pochutec.

The speakers of Nahuatl themselves often refer to their language as "Mexicano"[32] or a word derived from the Nahuatl word for "commoner" "mācehualli"[33]. The Pipil of El Salvador do not call their own language "Pipil" as most linguists do, but rather "Nawat"[34]. The Nahuas of Durango call their language "Mexicanero"[35]. Speakers of Nahuatl of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec call their language "mela'tajtol" - "the straight language". Some speech communities also use the word "Nahuatl" about their language although this seems to be a recent practice. It is common practice for linguists referring to specific dialects of nahuatl to speak of "Nahuatl" adding the village or area where it is spoken as a qualifier, e.g. "Nahuatl of Acaxochitlan".

Genealogy

The Nahuatl languages are related to the other Uto-Aztecan languages spoken by peoples such as the Hopi, Comanche, Paiute and Ute, Pima, Shoshone, Tarahumara, Yaqui, Tepehuán, Huichol and other peoples of western North America. They all belong to the Uto-Aztecan linguistic family which is one of the largest and best studied language families of the Americas consisting of at least 61 individual languages, and spoken from the United States to El Salvador. This is a grouping on the same order as Indo-European.

The first linguist to recognize the relationship between the northern Shoshonean languages with the southern Aztecan languages was Hubert Howe Bancroft, and the unity was confirmed in the classification of Daniel Garrison Brinton in 1891, the first classification to use the term "Uto-Aztecan" for the language family .[36]

The subgroupings of the Nahuan dialects and languages have been the subject of discussions among linguists for the past 50 years. In the early 20th century the first classifications of the Nahuan languages were proposed. Walter Lehmann suggested a basic split between languages which had the /tl/ sound and other which had /t/.[37] In 1939 another classification was proposed by B. L. Whorf which distinguished "Nahuat", the dialects with /t/ from "Aztec" the dialects with /tl/. at first the assupmtion of linguists was that /t/ was the original phoneme and had changed into /tl/ in some dialects only.[38] Another classification distinguishing between dialects with /tl/, /t/ and /l/ was proposed by Juan Hasler in the 1950'es but this and the earlier classifications have been criticized by Canger[39] for suffering from methodological flaws and for assuming that the t-tl-l trichotomy reflected an important historical division among the dialects. This assumption however was refuted by Lyle Campbell and Ronald Langacker in 1978 who showed that all the aztecan languages had shared the development of */t/ to /tl/ but that subsequently some dialects had changed the /tl/ back to /t/ or /l/. [40]

The most recent authoritative classifications of the Nahuan languages have been done by Yolanda Lastra de Suárez[41] and by Una Canger[42]. Both classifications are based on dialectological research focusing on the delineation of isoglosses based on differences in phonology, grammar and vocabulary. The two classifcations are largely identical, but vary on the status of the dialects of La Huasteca which Canger places in the central group but are placed by Lastra in a group unto themselves.

The classification below is based on that of Lastra in combination with the classification of Campbell[43] for the higher level groupings.

- Uto-Aztecan 5000 BP*

- Shoshonean (Northern Uto-Aztecan)

- Sonoran**

- Aztecan 2000 BP (a.k.a. Nahuan)

- Pochutec — Coast of Oaxaca

- General Aztec (Nahuatl)

- Western periphery

- Eastern Periphery

- Huasteca

- Center

See the Nahuatl dialects page for further discussion of the sub-categories of General Aztec, which are somewhat controversial.

- *Estimated split date by glottochronology (BP = Before the Present).

- **Some scholars continue to classify Aztecan and Sonoran together under a separate group (called variously "Sonoran", "Mexican", or "Southern Uto-Aztecan"). There is increasing evidence that whatever degree of additional resemblance there might be between Aztecan and Sonoran when compared with Shoshonean is probably due to proximity contact, rather than to a common immediate parent stock other than Uto-Aztecan.

Phonology of Nahuan languages

Historical phonological changes

The Nahuan subgroup of Uto-Aztecan is classified partly by a number of shared phonological changes from reconstructed Proto-Uto-Aztecan to the attested Nahuan languages. The changes shared between the Nahuan languages are the basis for the reconstruction of the intermediate stage of Proto-Nahuan. Some of these changes shared by all Nahuan languages are:

- Proto-Uto-Aztecan *t becomes Proto-Nahuan lateral affricate *tl before Proto-Uto-Aztecan *a

- Proto-Uto-Aztecan initial *p is lost in Proto-Nahuan.

- Proto-Uto-Aztecan *u merges with *i into Proto-Nahuan *i

- Proto-Uto-Aztecan sibilants *ts and *s split into *ts, *ch and *s, *ʃ respectively.

- Proto-Uto-Aztecan fifth vowel reconstructed as *ɨ or *ə merged with *e into Proto-Nahuan *e

- a large number of metatheses in which Proto-Uto-Aztecan roots of the shape *CVCV have become *VCCV.

The table below presents some of the changes that are reconstructed from Proto-Uto-Aztecan to Proto-Nahuan.

Table of reconstructed changes from Proto-Uto-Aztecan to Proto-Nahuan

| PUA | Proto-Nahuan |

| *ta:ka "man" | *tla:ka-tla "man" |

| *pahi "water" | *a:-tla "water" |

| *muki "to die" | *miki "to die |

| *pu:li "to tie" | *ilpi "to tie" |

| *nɨmi "to walk" | *nemi "to live, to walk" |

From the changes common to all Nahuan languages the subgroup has diversified somewhat and giving a complete overview of the phonologies of Nahuan languages is not suitable here. However, the table below shows a standardised phonemic inventory based on the inventory of Classical Nahuatl. Many modern dialects have undergone changes from proto-Nahuan that have resulted in different phonemic inventories.

Consonants

Table of Nahuatl consonants

| Labial | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | |

| Stops | p | t | k / kʷ | ʔ (h) | |

| Fricatives | s | ʃ | |||

| Affricates | tɬ / ts | tʃ | |||

| Approximants | w | l | j | ||

| Nasals | m | n |

Vowels

Table of Nahuatl vowels

| front | central | back | ||||

| long | short | long | short | long | short | |

| high | iː | i | ||||

| mid | eː | e | oː | o | ||

| low | aː | a | ||||

Grammar

The Nahuatl languages are agglutinative, polysynthetic languages that make extensive use of compounding, incorporation and derivation. That is, they can add many different prefixes and suffixes to a root until very long words are formed. Very long verbal forms or nouns created through incorporation and accumulation of prefixes are not uncommon in literary works. This also means that new words can be created at a moment's notice.

A minority of linguists consider the typology of Nahuatl to be oligosynthetic. This was first proposed by Benjamin Whorf in the early 20th Century. However, by the mid-1950s, this view was largely dismissed by the linguistic community.

Vocabulary

Loanwords from Nahuatl in other languages

Many Nahuatl words have been borrowed into the Spanish language, many of which are terms designating things indigenous to the American continent. Some of these loans are restricted to Mexican or Central American Spanish, but others have entered all the varieties of Spanish in the world and a number of them, such as "chocolate", "tomato" and "avocado" have made their way into many other languages via Spanish. For example, because of extensive Mexican-Philippine contacts during Spanish colonialism in both regions, there are an estimated 250 words of Nahuatl origin in the Tagalog language. Likewise a number of English words have been borrowed from Nahuatl through Spanish. Two of the most prominent are undoubtedly chocolate (from xocolātl, 'chocolate drink', perhaps literally 'bitter-water') and tomato (from (xi) tomatl). But there are others, such as coyote (coyotl), avocado (ahuacatl) and chile or chili (chilli). The brand name Chiclets is also derived from Nahuatl (tzictli 'sticky stuff, chicle'). Other English words from Náhuatl are: Aztec, (aztecatl); cacao (cacahuatl 'shell, rind'); mesquite (mizquitl); ocelot (ocelotl); shack (xacalli), and more.

Many well-known toponyms also come from Nahuatl, including Mexico (mexihco) and Guatemala (cuauhtēmallan).

In Mexico many words for common everyday concepts attest to the close contact between Spanish and Nahuatl:

- achiote, aguacate, ajolote, amate, atole, axolotl, ayate, cacahuate, camote, capulín, chapopote, chayote, chicle, chile, chipotle, chocolate, cuate, comal, copal, coyote, ejote, elote, epazote, escuincle, guacamole, guajolote, huipil, huitlacoche, hule, jícama, jícara, jitomate, malacate, mecate, metate, metlapil, mezcal, mezquite, milpa, mitote, molcajete, mole, nopal, ocelote, ocote, olote, paliacate, papalote, pepenar, petate, peyote, pinole, popote, pozole, quetzal, tamal, tianguis, tlacuache, tomate, zacate, zapote, zopilote.

(The persistent -te or -le endings on these words are Spanish reflexes of the Nahuatl 'absolutive' ending -tl, -tli, or -li, which appears on (most) nouns when they are not possessed or in the plural.)

Writing systems

At the time of the Spanish conquest, Aztec writing used mostly pictographs supplemented by a few ideograms. When needed, it also used syllabic equivalences; Father Durán recorded how the tlahcuilos (codex painters) could render a prayer in Latin using this system, but it was difficult to use as it was still in development. This writing system was adequate for keeping such records as genealogies, astronomical information, and tribute lists, but could not represent a full vocabulary of spoken language in the way that the writing systems of the old world or of the Maya civilization could. The Aztec writing was not meant to be read, but to be told; the elaborate codices were essentially pictographic aids for teaching, and long texts were memorized.

The Spanish introduced the Roman script, which was then utilized to record a large body of Aztec prose and poetry, a fact which somewhat mitigated the devastating loss of the thousands of Aztec manuscripts which were burned by the Spanish. Important lexical works (e.g. Molina's classic Vocabulario of 1571) and grammatical descriptions (of which Horacio Carochi's 1645 Arte is generally acknowledged the best) were produced using variations of this orthography. Carochi's ortography used two different accents: a macron to represent long vowels and a grave for the saltillo.

The classic orthography is not perfect, and in fact there were many variations in how it is applied, due in part to dialectal differences and in part to differing traditions and preferences that developed. (The writing of Spanish itself was far from totally standardized at the time.) Today, although almost all written Nahuatl uses some form of Latin-based orthography, there continue to be strong dialectal differences, and considerable debate and differing practices regarding how to write sounds even when they are the same. Major issues are

- whether to follow Spanish in writing the /k/ sound sometimes as c and sometimes as qu or just to use k

- how to write /kʷ/

- what to do about /w/, the realization of which varies considerably from place to place and even within a single dialect

- how to write the "saltillo", phonetically a glottal stop ([ʔ]) or an [h], which has been spelled with j, h, and a straight apostrophe ('), but which traditionally was often omitted in writing.

There are a number of other issues as well, such as

- whether and how to represent vowel length

- how and whether to represent sound variants (allophones) which sound like different Spanish sounds [phonemes], especially variants of o which come close to u

- to what extent writing in one variant should be adapted towards what is used in other variants.

The Secretaría de Educación Pública (Ministry of Public Education) has adopted an alphabet for its bilingual education programs in rural communities in Mexico in which k is used and /w/ is written as u, and this decision has been controversial; SEP's modern ortography does not recognise saltillo nor long vowels so many people still prefer the classical ortography. The recently established (2004) "Instituto Nacional de Lenguas Indígenas" (INALI) will also be involved in these issues.

- For the pictographic writing system used by the precolumbian Nahua peoples see also Aztec writing and Aztec Codices

- For more detail about the different orthographies used to transliterate Nahuatl in the Latin script see Nahuatl transcription

The Nahuatl edition Wikipedia has adopted a classical Carochi-based writing system, including the use of long accents (macrons) for represent long vowels /ā/, /ē/, /ī/ and /ō/. The 25-letter alphabet is:

Notes:¨

- "cu" and "hu" are inverted to "uc" and "uh" when occuring at the end of a syllable.

- These (*) letters have not capital form except in foreign names.

- "h" is used as saltillo.

Notes

- ^ This word has several variant spellings, which include: Náhuatl, Naoatl, Nauatl, Nahuatl, Nawatl. In Mexican Spanish the standard spelling is náhuatl with an accent on the first syllable. (The n is lower case because Spanish does not capitalize language names.)

- ^ also called Nahuan.

- ^ Suárez, 1983, p. 149

- ^ Canger, 1980, p. 13

- ^ See Mesoamerican languages#Language vs. Dialect for a discussion on the difference between "languages" and "dialects" in Mesoamerica

- ^ reports on nahuan languages

- ^ Canger, 1988

- ^ ley General de derechos lingüisticos de los pueblos indígenas {es icon}

- ^ Canger (1980, p.12)

- ^ Kaufman (2001, p.12).

- ^ Suárez (1983, p.149).

- ^ Kaufman (2001).

- ^ Fowler (1985, p.38).

- ^ Kaufman (2001).

- ^ Canger (1988, p.64).

- ^ Canger, 1980, p.14

- ^ Suárez 1983 p5

- ^ Suárez 1983 p165

- ^ Campbell 1985

- ^ According to the Nawat Language Recuperation Initiative homepage http://www.compapp.dcu.ie/~mward/irin/index.htm numbers maybe be anywhere from 20 to 200 speakers

- ^ Boas, 1917

- ^ Hill & Hill 1986; Brockaway 1979

- ^ Wolgemuth 2002

- ^ Flores Farfán, 1999

- ^ Beller & Beller, 1979

- ^ Tuggy, 1979

- ^ Sischo 1979

- ^ Canger, 2001

- ^ Flores Farfán (2002, p.229).

- ^ Launey, 1992, p. 116

- ^ Canger, 1988

- ^ Hill & Hill, 1986

- ^ This is the case for Nahuatl of Tetelcingo, Morelos whose speakers call their language "mösiehuali" (Tuggy 1979)

- ^ Campbell 1985

- ^ Canger, 2001

- ^ Campbell, 1997, p. 135.

- ^ Canger, 1988, p. 31

- ^ Canger, 1988, p. 34

- ^ Canger, 1988

- ^ Campbell & Langacker, 1978, 306

- ^ Lastra de Suárez, 1986

- ^ Canger, 1988

- ^ Campbell, 1997

Bibliography

- Beller, Richard (1979). "Huasteca Nahuatl". In Ronald W. Langacker (ed.) (ed.). Studies in Uto-Aztecan Grammar 2: Modern Aztec Grammatical Sketches. Summer Institute of Linguistics Publications in Linguistics, 56. Dallas, TX: Summer Institute of Linguistics and the University of Texas at Arlington. pp. pp.199–306. ISBN 0883120720. OCLC 6086368.

{{cite book}}:|editor=has generic name (help);|pages=has extra text (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); templatestyles stripmarker in|author=at position 1 (help); templatestyles stripmarker in|coauthors=at position 5 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Boas, Franz (1917). "El dialecto mexicano de Pochutla, Oaxaca". International Journal of American Linguistics. 1 (1). Chicago: University of Chicago Press: pp.9–44. ISSN 0020-7071. OCLC 56221629.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help); templatestyles stripmarker in|author=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) Template:Es icon - Campbell, Lyle (1985). The Pipil Language of El Salvador. Mouton Grammar Library (No. 1). Berlin: Mouton Publishers. ISBN 0-89925-040-8. OCLC 13433705.

{{cite book}}: templatestyles stripmarker in|author=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Campbell, Lyle (1997). American Indian Languages: The Historical Linguistics of Native America (Oxford Studies in Anthropological Linguistics, 4). New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-195-09427-1.

{{cite book}}: templatestyles stripmarker in|author=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Campbell, Lyle (1978). "Proto-Aztecan vowels: Parts I-III". International Journal of American Linguistics. 44. Chicago: University of Chicago Press: pp.85–102, 197–210, 262–79. ISSN 0020-7071.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); templatestyles stripmarker in|author=at position 1 (help); templatestyles stripmarker in|coauthors=at position 5 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Carochi, Horacio (1983) [1645]. Arte de la lengua mexicana: con la declaración de los adverbios della (Reprint). México D.F.: Porrúa.

{{cite book}}: templatestyles stripmarker in|author=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) Template:Es icon Template:Nah icon - Canger, Una (1980). Five Studies Inspired by Náhuatl Verbs in -oa. Travaux du Cercle Linguistique de Copenhague, Vol. XIX. Copenhagen: The Linguistic Circle of Copenhagen; distributed by C.A. Reitzels Boghandel. ISBN 87-7421-254-0. OCLC 7276374.

{{cite book}}: templatestyles stripmarker in|author=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Canger, Una (1988). "Nahuatl dialectology: A survey and some suggestions". International Journal of American Linguistics. 54 (1). Chicago: University of Chicago Press: pp.28–72. ISSN 0020-7071.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help); templatestyles stripmarker in|author=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Canger, Una (2001). Mexicanero de la Sierra Madre Occidental. Archivo de Lenguas Indígenas de México, #24. México D.F.: El Colegio de México. ISBN 968-12-1041-7. OCLC 49212643.

{{cite book}}: templatestyles stripmarker in|author=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) Template:Es icon - Dakin, Karen (1982). La evolución fonológica del Protonáhuatl. México D.F.: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Investigaciones Filológicas. ISBN 968-58-0292-0. OCLC 10216962.

{{cite book}}: templatestyles stripmarker in|author=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) Template:Es icon - Flores Farfán, José Antonio (1999). Cuatreros Somos y Toindioma Hablamos. Contactos y Conflictos entre el Náhuatl y el Español en el Sur de México. Tlalpán D.F.: Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios Superiores en Antropología Social. ISBN 968-49-6344-0. OCLC 42476969.

{{cite book}}: templatestyles stripmarker in|author=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) Template:Es icon - Flores Farfán, José Antonio (2002). "The Use of Multimedia and the Arts in Language Revitalization, Maintenance, and Development: The Case of the Balsas Nahuas of Guerrero, Mexico" (PDF). In Barbara Jane Burnaby and John Allan Reyhner (Eds.) (ed.). Indigenous Languages across the Community. Proceedings of the Annual Conference on Stabilizing Indigenous Languages (7th, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, May 11–14, 2000). Flagstaff, AZ: Center for Excellence in Education, Northern Arizona University. pp. pp.225–236. OCLC 95062129. ISBN 0-9670554-2-3.

{{cite conference}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Unknown parameter|booktitle=ignored (|book-title=suggested) (help); templatestyles stripmarker in|author=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Fowler, William R., Jr. (1985). "Ethnohistoric Sources on the Pipil Nicarao: A Critical Analysis". Ethnohistory. 32 (1). Durham, NC: Duke University Press and the American Society for Ethnohistory: pp.37–62. ISSN 0014-1801. OCLC 62217753.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help); templatestyles stripmarker in|author=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Gordon, Raymond G., Jr. (Ed.) (2005). Ethnologue: Languages of the World (online version) (Fifteenth edition ed.). Dallas, TX: SIL International. ISBN 1-55671-159-X. OCLC 60338097. Retrieved 2006-12-06.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help); templatestyles stripmarker in|author=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Hill, Jane H. (1986). Speaking Mexicano: Dynamics of Syncretic Language in Central Mexico. Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press. ISBN 0-816-50898-4. OCLC 13126530.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); templatestyles stripmarker in|author=at position 1 (help); templatestyles stripmarker in|coauthors=at position 5 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Kaufman, Terrence (2001). "The history of the Nawa language group from the earliest times to the sixteenth century: some initial results" (PDF). Project for the Documentation of the Languages of Mesoamerica. Retrieved 2007-10-07.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|edtion=ignored (help); templatestyles stripmarker in|author=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Launey, Michel (1980). Introduction à la langue et à la littérature aztèques. Paris.

{{cite book}}: templatestyles stripmarker in|author=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) Template:Fr icon - Launey, Michel (1992). Introducción a la lengua y a la literatura Náhuatl. México D.F.: UNAM.

{{cite book}}: templatestyles stripmarker in|author=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) Template:Es icon - Olmos, Fray Andrés de (1993) [1547]. Arte de la lengua mexicana concluído en el convento de San Andrés de Ueytlalpan, en la provincia de Totonacapan que es en la Nueva España. México D.F.

{{cite book}}:|format=requires|url=(help); templatestyles stripmarker in|author=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) Template:Es icon - Rincón, Antonio del (1885) [1595]. Arte mexicana compuesta por el padre Antonio del Rincón. México D.F.

{{cite book}}:|format=requires|url=(help); templatestyles stripmarker in|author=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) Template:Es icon - Sahagún, Fray Bernardino de (1950&ndash71) [ca. 1540–85]. Charles Dibble and Arthur Anderson {eds.) (ed.). Florentine Codex. General History of the Things of New Spain (Historia General de las Cosas de la Nueva España). vol I-XII. Santa Fe, NM.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help); templatestyles stripmarker in|author=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Sischo, William R. (1979). "Michoacán Nahual". In Ronald W. Langacker (ed.) (ed.). Studies in Uto-Aztecan Grammar 2: Modern Aztec Grammatical Sketches. Summer Institute of Linguistics Publications in Linguistics, 56. Dallas, TX: Summer Institute of Linguistics and the University of Texas at Arlington. pp. pp.307–380. ISBN 0883120720. OCLC 6086368.

{{cite book}}:|editor=has generic name (help);|pages=has extra text (help); templatestyles stripmarker in|author=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Suárez, Jorge A. (1983). The Mesoamerian Indian Languages (Cambridge Languages Surveys). London: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-22834-4.

{{cite book}}: templatestyles stripmarker in|author=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Sullivan, Thelma D. (1988). Compendium of Náhuatl Grammar. Salt Lake City, UT.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); templatestyles stripmarker in|author=at position 1 (help); templatestyles stripmarker in|coauthors=at position 5 (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Tuggy, David H. (1979). "Tetelcingo Náhuatl". In Ronald W. Langacker (ed.) (ed.). Studies in Uto-Aztecan Grammar 2: Modern Aztec Grammatical Sketches. Summer Institute of Linguistics Publications in Linguistics, 56. Dallas, TX: Summer Institute of Linguistics and the University of Texas at Arlington. pp. pp.1–140. ISBN 0883120720. OCLC 6086368.

{{cite book}}:|editor=has generic name (help);|pages=has extra text (help); templatestyles stripmarker in|author=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Wimmer, Alexis (2006). "Dictionnaire de la langue nahuatl classique" (online version).

{{cite web}}: templatestyles stripmarker in|author=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) Template:Fr icon Template:Nah icon - Wolgemuth, Carl (2002). Gramática Náhuatl (melaʼtájto̱l) de los municipios de Mecayapan y tatahuicapan de Juárez, Veracruz (2nd edition ed.).

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help); templatestyles stripmarker in|author=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

Further reading

- Andrews, J. Richard, Introduction to Classical Nahuatl, Austin, Texas, 1975 (1st ed.), 2000 (2nd ed.).

- de Arenas, Pedro: Vocabulario manual de las lenguas castellana y mexicana. [1611] Reprint: México 1982

- Campbell, Joe and Frances Karttunen, Foundation course in Náhuatl grammar. Austin 1989

- Garibay K., Angel María : Llave de Náhuatl. Ed. Porrúa, SC706, México 2004.

- Garibay K., Angel María, Historia de la literatura náhuatl. México 1953

- Garibay K., Angel María, Poesía náhuatl. vol 1-3 México 1964

- Garibay K. Angel María, Panorama Literario de los Pueblos Nahuas., Ed. Porrúa, SC022, México, 2001.

- von Humboldt, Wilhelm (1767–1835): Mexicanische Grammatik. Paderborn/München 1994

- Jiménez, Doña Luz (?–1965): Life and Death in Milpa Alta. Norman 1972

- Karttunen, Frances, An analytical dictionary of Náhuatl. Norman 1992

- Karttunen, Frances, Between worlds: interpreters, guides, and survivors. New Brunswick 1994

- Karttunen, Frances, Náhuatl in the Middle Years: Language Contact Phenomena in Texts of the Colonial Period. Los Angeles 1976

- Kaufman, Terrence, (2001) Nawa linguistic prehistory, published at website of the Mesoamerican Language Documentation Project

- de León-Portilla, Ascensión H.: Tepuztlahcuilolli, Impresos en Náhuatl: Historia y Bibliografia. Vol. 1-2. México 1988

- León-Portilla, Miguel : Literaturas Indígenas de México. Madrid 1992

- Lockhart, James: Nahuatl as written : lessons in older written Nahuatl, with copious examples and texts, Stanford 2001

- Lockhart, James (ed): We people here. Náhuatl Accounts of the conquest of Mexico. Los Angeles 1993

- de Molina, Fray Alonso: Vocabulario en Lengua Castellana y Mexicana y Mexicana y Castellana. [1555] Reprint: Porrúa México 1992

- Siméon, Rémi: Dictionnaire de la Langue Náhuatl ou Mexicaine. [Paris 1885] Reprint: Graz 1963

- Siméon, Rémi: Diccionario de la Lengua Náhuatl o Mexicana. [Paris 1885] Reprint: México 2001

- Stiles, Neville Náhuatl in the Huasteca Hidalguense: A Case Study in the Sociology of Language PhD thesis, Centre for Latin American Linguistic Study, University of St. Andrews, Scotland. 1983

- The Nahua Newsletter: edited by the Center for Latin American and Caribbean Studies of the Indiana University (Chief Editor Alan Sandstrom)

- Estudios de Cultura Náhuatl: special interest-yearbook of the Instituto de Investigaciones Historicas (IIH) of the Universidad Autónoma de México (UNAM), Ed.: Miguel Leon Portilla

See also

- Category: Nahuatl words and phrases

- List of Spanish words of Indigenous American Indian origin

- Calīxatl Main Page of Nahuatl Wikipedia

- (See ¿Tleinca huēhuehtlahtōlli? (Why classic ortography?) for discussion in English and Spanish about what spelling and dialect of Nahuatl to use in it.)

External links

- Ethnologue reports on Náhuatl

- Ethnologue Náhuatl dialects

- Náhuatl Learning Resource List, by Ricardo J. Salvador

- Brief Notes on Classical Náhuatl, by David K. Jordan

- Nahuatl (Aztec) family, SIL-Mexico, with subsites on some specific variants

- Náhuatl Summer Language Institute, Yale University

- Náhuatl → English (Basic Dictionary, by Acoyauh)

- Spanish → Náhuatl, Náhuatl → Spanish (Ohui.net)

- Náhuatl-French dictionary Includes basic grammar

- Náhuatl Names An introduction to Náhuatl names.

- Books at Project Gutenberg in Nahuatl