Medieval cuisine is the variety of foods eaten by the various European cultures during the Middle Ages. Many of the changes that occurred in this period laid the foundations for the present national and regional cuisines of Europe, although the medieval cuisines were more geographically limited and less cosmopolitan than those of today. Transportation and communication during this period was slow and prevented the export of many foods, especially fresh fruit and meat, that today are commonplace in all industrialized nations. Still, the highly refined and exclusive foods eaten by the wealthy nobility were often considerably more internationalized and prone to foreign influences than the foodstuffs of the lower strata of society. The trends set by the consumption of royal and noble courts were still influential. All parts of the population wished to at least emulate them, especially the upper middle class of medieval towns.

In a time when famines were commonplace and social hierarchies often enforced with considerable brutality, food was an important marker of social status in a way that has no equivalent today. Other than practical economic unavailability of luxuries like imported spices, there were often decrees that outlawed the consumption of certain foods for individuals of certain social classes and sumptuary laws were used to limit the conspicuous consumption of the nouveau riche that weren't part of the nobility. Social norms also dictated that the food of the working classes should be less refined than that of the social elite since it was believed that hard manual labor required coarser and cheaper food. Contemporary medicine added to these notions recommending expensive tonics, theriacs and exotic spices to cure those of noble blood, while recommending the more odorous and lower ranked garlic to the common man.

Ingredients in cooking that were common to most of Europe at the time were verjuice, wine and vinegar. This combined with the widespread usage of sugar (among those who could afford it) gave many dishes a distinctly sweet-sour flavor. The most popular types of meat were pork and chicken, while beef was less common than today. Cod and herring formed the mainstay for a large proportion of the northern populations, but a wide variety of other species of both saltwater and freshwater fish were also readily consumed. Almonds, both sweet and bitter, were in widespread usage, eaten whole as garnish, or more commonly ground up, and used as a thickener in soups, stews, and sauces. Particularly popular was almond milk, which was one the most common substitutes for animal milk during Lent and fast.

Dietary norms

The influence of the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Church had a great impact on eating habits; consumption of meat was forbidden for a full third of the year for most Christians and all animal products such as eggs and dairy products (but not fish) were generally prohibited during Lent and fast. The church often acceded to demands for regional exceptions when non-animal alternatives were unavailable or simply unaffordable. Exempt from fasting regulations were children, the old, pilgrims, workers and beggars, but not the poor as long as they had some sort of shelter.

Medical science of the Middle Ages had a much greater influence on what was considered healthy and nutritious. One's lifestyle — including diet, exercise, appropriate social behavior, and approved medical remedies — was the way to good health, and all types of food were assigned certain properties that affected a person's health. All foodstuffs were also classified on scales ranging from hot to cold and moist to dry, categories which corresponded to the theory of four bodily humors, proposed by Galen, that dominated Western medical science from late Antiquity until the 17th century.

Meals

There were typically two meals per day in medieval society: dinner (the medieval equivalent of the modern lunch) around noon and a lighter supper later at night. Moralists of the day frowned on the idea of breaking the overnight fast too early in the day, and members of the church and the cultivated gentry avoided it. Breakfast was, for practical reasons, still eaten by a large proportion of working men and having an early morning meal was tolerated for young children, women, the elderly and the sick. Most men tended to be ashamed of it and would not admit to succumbing to such a weak practicality. Lavish dinner banquets and late night reresopers with considerable amounts of alcohol were considered immoral. Especially the latter was associated with vices like gambling, crude language, drinking, and lewd flirtation. Minor meals and snacks were common (though also disliked by the church), and working men commonly received an allowance from their employers in order to purchase food to be eaten during breaks.[1]

Food was mostly eaten with spoons or with one's bare hands. Knives were used at the table, but most people were expected to bring their own, and only favored guests were given their own knife at a dinner table. The latter were usually shared with at least one other dinner guest unless one was of very high rank or well-acquainted with the host. Before the meal and after each course shallow basins filled with water and linen towels were offered to guests so they could wash their hands and great emphasis was put on cleanliness. Shared drinking cups was common practice even at lavish banquets for all but those who sat at the high table, as was the standard etiquette of breaking bread and carving meat for one's fellow diners. The collective and hierarchical nature of medieval society was reinforced in these rules of etiquette where the lower ranked were expected to help those in a higher position, the younger the older, and men women. Overall, banquet and fine dining was a predominantly male affair. It was, for example, uncommon for anyone but the most honoured of guests to bring his wife, or for that matter her ladies-in-waiting. Since social codes made it difficult for women to uphold the stereotype of being neat, delicate and immaculate while enjoying a sumptuous feast, the wife of the host often dined in private along with her entourage. She could then join dinner only after the potentially messy and practical business of eating was finished.[2]

Forks for eating were not in widespread usage in Europe until the Modern era and early on it was limited to Italy, most likely because the most common staple food was pasta. Still, it was not until the 14th century that the fork had become common among Italians of all social classes. The change in attitudes can be illustrated by the reactions to the table manners of the Byzantine princess Theodora Doukaina in the 11th century. She was the future wife of the Doge of Venice, Domenico Selvo, and caused considerable dismay among upstanding Venetians. The foreign consort's insistence on having her food cut up by her eunuch servants and then eating the pieces with a golden fork shocked and upset the diners so much that the Bishop of Ostia later referred to her as "...the Venetian Doge's wife, whose body, after her excessive delicacy, entirely rotted away."[3]

Cereals

The phrase Our Daily Bread is largely figurative to most Europeans today, but was a very concrete reality during the Middle Ages. Food intake among all social classes consisted mainly of cereals, usually in the form of bread and, to a lesser extent, pasta. Estimates of bread consumption in various regions have turned out to be very similar; around 1–1.5 kg (2–3 lb) of bread per person per day. The most common grains were rye, barley, buckwheat, millet and oat. Rice remained a fairly expensive import for most of the Middle Ages and was grown in northern Italy only towards the end of the period. Wheat was common all over Europe and was considered to be the most nutritious of all grains, but was far more expensive since it carried with it a higher social prestige. The finely sifted white flour that modern Europeans are most familiar with was reserved for the bread of the upper classes, while those of lower status ate bread that became coarser, darker and of a higher bran content the lower one was on the social ladder. During time of grain shortage or outright famine, flour was often made by supplementing grains with chestnuts, dried legumes, acorns, ferns and a wide variety of vegetable matter. The alternative for those who lacked the proper facilities to bake bread or simply couldn't afford it was a plain porridge or gruel.

One of the most common constituents of a medieval meal, either as part of a banquet or as a small snack were sops, pieces of bread with which a liquid like wine, soup, broth or sauce could be soaked up and eaten. Another common sight at the medieval dinner table was the frumenty, a thick wheat porridge often boiled in a meat broth and seasoned with spices. Porridges were also made of every type of grain and could be served as desserts or sick dishes if boiled in milk (or almond milk) and sweetened with sugar. Pies[4] filled with meats, eggs, vegetables or fruit were common throughout Europe as were turnovers, fritters, donuts and many similar pastries. By the late Middle Ages biscuits and wafers had become very popular and came in many varieties. Grain, either as bread crumbs or flour, was also the most common thickener of soups and stews.

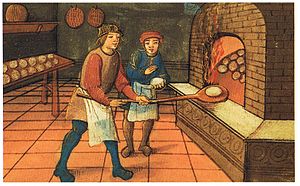

The importance of bread as a daily staple meant that bakers played a crucial role in any medieval community. Among the first town guilds to be organized were, naturally, the bakers' and laws and regulations were passed to keep the bread prices stable. The English Assize of Bread and Ale of 1266 listed extensive tables where the size, weight and price of a loaf of bread was set in relation to wheat prices. The tables were later supplemented by adding the cost of everything from firewood and salt to a dog and even the baker's own wife. Bakers that were caught cheating their customers could received severe penalties. A common form of punishment was to fasten the offender to a sleigh and drag him around town with the adulterated loaf tied around his neck.[5]

Bread was put to use for more than just eating: though often of wood or metal, trenchers that served as dinner plates in affluent households were made out of old bread made from unsifted flour far into the early modern era, and bread was used to wipe off knives when passing them to the next diner or before fishing out salt from the shared salt cellars. Even the seemingly carefree handling of hot metal serving plates was occasionally achieved with slices of bread neatly tucked into the hands of servants, out of sight of high-ranking diners.[6]

Fruit and vegetables

While grains were the primary constituent of almost every meal, various vegetables such as cabbage, beet, onion, garlic and carrot were also common foodstuffs. However, though many of these plants were eaten on an almost daily basis by peasants and workers, they were generally considered less prestigious than all forms of meat. The cookbooks that appeared in the late Middle Ages only contain a small percentage of recipes using vegetables other than side dishes and the occasional potages. The primary forms of preparation were in soups or stews. The orange carrot that is the most common today did not appear until the 17th century. Various legumes, like chickpeas, fava beans and peas were also common and important sources of protein.

Fruit was popular and was served fresh (even if the medical science of the time discouraged it), dried, or preserved. Since sugar and honey were expensive, it was common to include many types of fruit in dishes that called for sweeteners of some sort. The fruits of choice in the south were lemons, citrons, bitter oranges (the sweet type was not introduced until several hundred years later), pomegranates, quinces and, of course, grapes. Further north apples, pears, plums and strawberries were more common. Figs and dates were eaten all over Europe, but remained more exclusive in the northern regions where they had to be imported.

Common and often basic ingredients in many modern European cuisines like potatoes, kidney beans, cacao, tomatoes, chili peppers and maize were not available to Europeans until the late 15th century with the discovery of the Americas, and even then it often took a long time for the new foodstuffs to be accepted by society at large.

Drink

Water is often seen today as a common and neutral choice to drink with a meal. In the Middle Ages concerns over purity, medical recommendations and its low prestige value made it a less favorable option and alcoholic beverages like wine, beer, mead, cider and perry were preferred. All of them were considered to be more nutritions and beneficial to digestion than water as well as being less prone to putrefaction due to the alcohol content. Wine was consumed on a daily basis in most of France and all over the Western Mediterranean where grapes were cultivated. Further north it remained the preferred drink of the bourgeoisie and the nobility who could afford it, and far less common among peasants and workers. The drink of commoners in the northern parts of the continent was primarily beer or ale; due to problems with preservation of this beverage for any long period (especially before the introduction of hops) it was mostly consumed fresh; it was therefore cloudier and perhaps of a lower alcohol content than the typical modern equivalent. Plain milk was not consumed by adults except the poor, sick, very young or elderly, and then usually as buttermilk or whey. Fresh milk was overall less common than other dairy products because of the lack of technology to keep it from spoiling.[7]

Wine

Wine had the highest social prestige of all drinks and was also considered to be the healthiest alternative. According to the dietetics based on Galenic theory it was considered to be hot and dry (hence the modern use of "dry" in describing the flavour of wine). Unlike water or beer, which were considered to be cold and moist, consumption of wine in moderation (especially red wine) was, among other things, believed to aid digestion, generate good blood and brighten the mood. The quality of wine differed considerably according to vintage, the type of grape and more importantly, on the number of grape pressings. The first pressing was made into the finest and most expensive wines which were reserved for the upper classes. The second and third pressings were subsequently of lower quality and alcohol content. Common folk usually had to settle for a cheap white or rosé from a second or even third pressing, meaning that it could be consumed in quite generous amounts without leading to heavy intoxication. For the poorest (or hard-line religious ascetics), watered-down vinegar would often be the only available choice.

The aging of high quality red wines required more specialized knowledge as well as expensive storage and equipment, and resulted in an even more expensive and exclusive end product. Judging from the advice given in many medieval documents on how to salvage wine that bore the tell-tale signs of going bad, preservation must have been a widespread problem. Even if vinegar was a common ingredient in many dishes, there was only so much of it that could be used at one time. In the 14th century cookbook Le Viandier there are several methods for salvaging spoiling wine; making sure that the wine barrels are always topped up or adding a mixture of dried and boiled white grapeseeds with the ash of dried and burnt lee of white wine were both effective bactericides, even if the chemical processes were not understood at the time. Spiced or mulled wine was not only popular among the affluent, but also considered especially healthy by physicians. Wine was believed to act as a kind of vaporizer and a conduit of other foodstuffs to every parts of the body, and the addition of fragrant and exotic spices would make it even more wholesome. Spiced wines were usually made by mixing an ordinary (red) wine with an assortment of spices such as ginger, cardamom, pepper, grains of paradise, nutmeg, cloves and sugar. These would be contained in small bags which were either steeped in wine or had liquid poured over them to produce hypocras and claret, and by the 14th century bagged spice mixes could be bought ready-made from spice merchants.[8]

Meat

While all forms of wild game were popular among those who could obtain it, the majority of meat came from domesticated animals. Beef was not as common as today because raising cattle was fairly labor-intensive, requiring pastures and feed, and oxen and cows were much more valuable as draught animals and for producing milk. The flesh of animals slaughtered when they were no longer able to serve was not particularly appetizing and therefore less valued. Far more common was pork, which required less attention and cheaper feed. Domestic pigs often ran freely even in towns and could be fed on just about any organic kitchen waste. Among the meats that today are not considered appropriate for food, hedgehog and squirrel were often mentioned in recipe collections.

A wide range of birds were eaten, including swans, peafowl, quail, partridge, storks, cranes, larks and just about any wild bird that could be hunted successfully. Swans and peafowl were often domesticated, but were only eaten by the social elite and were more praised for their fine appearance (often used to create stunning subtleties) than the quality of their meat. As today, geese and ducks had been domesticated but were not as popular as the chicken, the fowl equivalent of the pig. Interestingly enough, barnacle geese were by legend considered to spawn not by laying eggs like other birds, but by growing in barnacles and were hence considered acceptable food for fast and Lent.[9]

The amount of meat consumed varied considerably and there is generally a lack of precise sources from all regions and periods. Some materials can give a rough estimate of what could be considered normal some segments of society. Account books from convents and towns in what is modern-day Germany suggested that the daily rations of meats could be extremely high for some groups, even when compared with modern day consumption. A study of 14th century records from Berlin, Strassbourg and Frankfurt-an-der-Oder by German historians suggests that even city dwellers of relatively low status consumed from 500 g to 1 kg (1–2 pounds) of meat a day throughout the year.[10]

Seafood

Although ranked lower in prestige than other animal meats, and often seen as merely an alternative to meat on fast days dictated by the church, seafood was still the mainstay of many coastal populations. Especially important was the fishing and trade in herring and cod in the Atlantic and the Baltic Seas. The herring was of enormous significance to the economy of much of Northern Europe, and it was one of the most common commodities traded by the Hanseatic League. Kippers made from herring caught in the North Sea could be found in markets as far away as Constantinople. While large quantities of fish were eaten fresh, a large proportion was salted, dried, and, to a lesser extent, smoked. "Stockfish", cod that was split down the middle, fixed to pole and dried, was very common, even though preparing it for consumption was rather elaborate, involving beating the fish with a mallet for several hours and soaking it in water a few days before preparation. A wide range of mollusks including oysters, mussels and scallops were eaten by coastal Mediterranean populations, and freshwater crayfish were generally seen as a desirable alternative to meat during religious non-fish days. Compared to meat, fish was much more expensive for the inland population, especially in Central Europe, and therefore not an option for most. Fresh water fish such as pike, carp, bream, perch, lamprey, and trout were common. Though actually marine mammals, whales and porpoises were considered to be fish in the Middle Ages and were allowed on fast days. Through rather original reasoning, based on that they spent most of their time in the water, the tails of beavers, but not the rest of the body, were considered to be fish.[9]

Herbs and spices

Spices were among the most luxurious products available in the Middle Ages, the most common being pepper, cinnamon (and the cheaper alternative cassia), cumin, ginger and cloves. They all had to be imported from plantations in Asia and Africa, which made them extremely expensive. It has been estimated that around 1,000 tons of pepper and 1,000 tons of the other common spices were imported into Western Europe each year during the late Middle Ages. The value of these goods was the equivalent of a yearly supply of grain for 1.5 million people.[11] If pepper was the most common spice, the most exclusive was saffron, and was used as much for its vivid yellow-red color as for its flavor. Many spices that were common and fashionable during the period have today fallen into general disuse in European cooking, for example galingale, long pepper and cubeb. Grains of paradise, a relation of cardamom, are largely unknown to modern consumers, but were a mainstay of the the haute cuisine in northern France in the late Middle Ages and almost entirely replaced pepper in French recipe collections from this period.

Locally grown herbs were more affordable, and also used in upper-class food, but were then usually less prominant or included as coloring. Sage, mustard, and especially parsley were grown all over Europe and were in widespread usage, as were caraway, mint and fennel. Dill and mustard were both popular for flavoring all kinds of meat in German-speaking areas. Anise was used to flavor fish and chicken dishes and its seeds were served as sugar-coated comfits at the end of a meal.[9]

Sweets and desserts

Sugar was a very expensive luxury in the Middle Ages, and the consumption rates were very low by modern standards. Sugar cane could only be grown in the southernmost parts of Europe and the sugar beet was still several hundred years away. The most common sweeteners were honey, fresh and dried fruit and grape syrup. For the rich, marzipan and candied orange rinds were popular as sweets and confectionery in both France and Italy by the early 14th century. Several types of candied spices were commonly eaten after finer meals, similar to modern day after-dinner mints. For those who could not afford sugar or honey, parsnips and turnips were viable alternatives for sweetening a dish.

Regional variations

Britain

There is relatively little known about the eating habits of the Anglo-Saxons of the Early and High Middle Ages before the Norman conquest in 1066. Ale was the drink of choice of both commoners and nobles, and the known dishes included various stews, simple broths, and soups. The level of refinement was low, and international influence fairly insignificant. This all changed in the 11th century after the Norman invasion. With the invaders came a new and less provincial gentry, and new eating habits, especially for the nobility. While traditional British cooking today is not regarded with high esteem internationally, the Medieval Anglo-Norman cooks were considerably more refined and more cosmopolitan. It has previously been believed that the Anglo-Norman cuisine was mostly similar to that of France, but recent study has shown that many recipes had unique English traits. This was based partly on the different available foodstuffs on the British Isles, but more due to influence from Arab cuisine through the Norman conquest of Sicily. The Arab invaders in the 9th century had cultivated their lifestyle culturally and economically to such a degree that the Norman invaders inherited and adapted many of their habits, including cooking styles. Norman participation in the crusades also brought them into contact with Middle Eastern and Byzantine cooking.[12]

The subtlety, the fanciful and highly decorative surprise dish used to separate one course from another, was brought to new levels of complexity and refinement by the English chefs. Among the specialties were pommes dorée ("gilded apples"), meatballs of mutton or chicken colored with saffron or a glaze of egg yolk. The Anglo-Norman variant, pommes d'orange, were flavored and coloured with the juice of bitter oranges.[13]

Northern France

Northern French cuisine had many similarities to the Anglo-Norman French across the channel, but also had its own specialties. Typical of the Northern French kitchen were the potages and broths, and French chefs excelled in the preparation of meat, fish, roasts, and the sauces that were considered appropriate to each dish. The use of dough and pasta, which was fairly popular in Britain at the time, was almost completely absent from recipe collections with the exception of a few pies. Nor were there any forms of dumplings or the fritters that were so popular in Central Europe. A common Northern French habit was to name dishes after famous and often exotic places and people.

A specialty among finer French chefs was the production of parti-colored dishes. These mimicked the late medieval fashion of wearing brightly colored clothing with two colors contrasting one another on either side of the garment, something that survived for a longer time in the costumes of court jesters. The common Western European dish blanc manger ("white dish") had a Northern French variant where one side was colored bright red or blue. Another recipe in Du fait de cuisine from 1420 described an entremet (the French equivalent of a subtlety) consisting of a roasted boar's head with one half colored green and the other golden yellow.[12]

Western Mediterranean

Roman influence on the entire Mediterranean region was so considerable that to this day, the basic foods of most of the region are wheat bread, olives, olive oil, wine, cheese, and roasted meat. The territories from the Atlantic to the Italian Peninsula, and especially the Catalan and Occitan-speaking areas were closely interrelated culturally and politically. The Muslim conquest of Sicily and southern Spain was highly influential on the cuisine by introducing new plants like lemons, pomegranates, eggplants and spices such as saffron. The coloring of food and many other cooking techniques were passed on by the Arab invaders to their European possessions and were gradually spread to regions further north.

Southern France

As with culture, the cuisine of southern French of the Middle Ages, corresponding to Languedoc and Provence, had much more in common with Italian and Iberian, especially Catalan cooking than with their neighbors to the north. Ingredients that distinguished in Southern cooking included chickpeas, pomegranates and lemons, all of which were grown locally. While pomegranate seeds were occasionally used as to decorate dishes further north, using its juice as a flavoring was unique to the south. The use of butter or lard was rare, salted meat for frying was common, and the preferred methods of cooking tended to be dry roasting, frying, or baking. For the latter, a trapa was often used, a portable oven that was filled with food and buried in hot ashes. Dishes still common today, like escabeche, a vinegar-based dish, and aillade, a garlic sauce, were well-established during the late Middle Ages. Evidence of influence from Muslim Spain can be found in the mention of matafeam, a Christian version of the originally Hispano-Jewish Sabbath stew adafina that used pork instead of lamb.

Only one minor recipe collection from the south has survived, written in a mix of Latin and Occitan, but some very concrete details have been extrapolated from Vatican archives from 1305–78 when Avignon was the seat of several popes. Though the lifestyles of the papal courts could often be very luxurious, the Vatican account books of the daily alms given to the poor describe some of what lower class food in the region was like. Food handed out consisted of bread, legumes, and some wine, occasionally supplemented with meat of low quality, cheese, fish, and oil.[12]

Montpellier, located on in Languedoc only a few miles from the coast, was a major center for trade, education in medicine, but was also famous for its espices de chamber or "parlor confections", a general term for sweets such as candied aniseed and ginger. The confectionery from the town was so renowned that the market value was twice as high as that of similar products of different origins. The town was also well-known for its spices and the wines with which they were flavored, like the ubiquitous hypocras.[14]

Byzantium

The culinary traditions of Roman times lived on in the Byzantine empire. Inherited from Greek traditions was the usage of olives and olive oil, wheat bread, and garós, the Greek term for garum, a sauce made out of fermented fish that was so popular as that it more or less replaced salt as the common food flavoring. The Byzantine kitchen was also influenced by Arab cuisine from which it imported the use of eggplants and oranges. Seafood was very popular and included tuna, lobster, mussels, oysters, murena, and carp. Towards the Late Middle Ages the habit of eating roe and caviar was also imported from the Black Sea region in the 11th century. Dairy products were consumed in the form of cheese (particularly feta), and nuts and fruits such as dates, figs, grapes, pomegranates, and apples. The choice of meats were lamb, and several wild animals like gazelles, wild asses, and suckling young in general. Meat was often salted, smoked or dried. Wine was popular, like elsewhere around the Mediterranean, and it was drink of choice among the higher social classes, where sweet wines like Muscat or Malmsey were popular. Among the lower classes, the common drink tended to be vinegar mixed with water. Like all Christian societies the Byzantines had to abide by the dietary restrictions of the church, which meant avoiding meats (and preferably general excesses) on Wednesdays and Fridays and during fast and Lent.

The Byzantine empire also became quite famous for its desserts, which included biscuits, rice pudding, quince marmalade, rose sugar and many types of soft drinks. The most common sweetener was honey, with sugar extracted from sugar cane being reserved for those who could afford it.

The food of the lower classes was mostly vegetarian and limited to olives, fruit, onions, and the occasional piece of cheese, or stews made from cabbage and salted pork. The standard meal of a shoemaker was described in a Byzantine poem, one of the Ptochoprodromika, as consisting of some cooked foods and an omelette followed by a hot salted pork with an unspecified garlic dish.[15]

Notes

- ^ Henisch chapter 2

- ^ Adamson p. 161–164,

- ^ Henisch p. 185–186

- ^ The modern standard pie with an edible bottom crust was not conceived until the 14th century.

- ^ Scully p. 35–38

- ^ Adamson p. 161–164

- ^ Adamson p. 48–51

- ^ Scully p. 138–146

- ^ a b c Adamson chapter 1

- ^ Nordberg pg. 40

- ^ Adamson p. 65; by comparison, the estimated population of Britain in 1340, right before the Black Death was only 5 million and a mere 3 million by 1450 (Fontana... p. 36)

- ^ a b c Adamson chapter 3

- ^ Regional Cuisines... chapter 2

- ^ Regional Cuisines... chapter 3, The South

- ^ Regional Cuisines... chapter 1

References

- Adamson Weiss, Melitta (2004), Food in Medieval Times ISBN 0-313-32147-7

- The Fontana Economic History of Europe: The Middle Ages (1972); J.C Russel Population in Europe 500-1500 ISBN 0-00-632841-5

- Henisch, Bridget Ann (1976), Fast and Feast: Food in Medieval Society ISBN 0-271-01230-7

- Nordberg, Michael (1984), Den dynamiska medeltiden ISBN 91-550-2786-5

- Regional Cuisines of Medieval Europe: A Book of Essays (2002), edited by Melitta Weiss Adamson ISBN 0-415-92994-6

- Scully, Terence (1995) The Art of Cookery in the Middle Ages ISBN 0-85115-611-8