| PLAC1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Aliases | PLAC1, CT92, OOSP2L, placenta specific 1, OOSP2B, placenta enriched 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| External IDs | OMIM: 300296; MGI: 1926287; HomoloGene: 11039; GeneCards: PLAC1; OMA:PLAC1 - orthologs | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Wikidata | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Placenta-specific protein 1 is a small (212 amino acid), secreted cell surface protein encoded on the X-chromosome by the PLAC1 gene. Since its discovery in 1999, PLAC1 has been found to play a role in placental development and maintenance, several gestational disorders including preeclampsia , fetal development and a large number of cancers.

Genomics

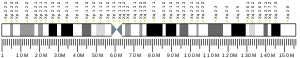

[edit]PLAC1 is located on the long arm of the X-chromosome at Xq26.3. The gene consists of six Exons spanning nearly 200Kb (GRCh38/hgs38; X:134,565,838 - 134,764,322). The entire coding sequence plus the 3’ UTR and part of the 5’ UTR constitute Exon 6 while Exons 1 – 5 contain variously spliced elements of the rest of the 5’UTR including two independently regulated promoters.

These two promoters, termed P1 (or distal) and P2 (or proximal) are located in Exons 1 and 4 respectively. They have been shown to produce transcripts simultaneously though P1 transcription predominates in cancers and P2 transcription predominates in placentae.[5]

Phylogenetics

[edit]From its initial description, the consensus is that PLAC1 is highly conserved and that this conservation reflects an important role in the establishment and maintenance of the placenta.[6] A detailed study of the PLAC1 gene and protein among 54 placental mammal species representing twelve crown orders confirms a high level of conservation under the control of strict purifying selection.[7] Further, comparative genomic sequences from two marsupials, the opossum (Mondelphis domestica) and the wallaby (Macropus eugenii), a monotreme, the platypus (Ornithorhynchus anatinus), two avians, the chicken (Gallus gallus) and the finch (Taeniopygia guttata), and two fish, the zebrafish (Danio rerio) and the stickleback (Gasterosteus arculeatus) spanning the synthenic X-chromosome region from PHD finger protein 6 (PHD6) through Factor 9 (F9) were screened for any sequences similar to PLAC1. The screen showed that PLAC1 appeared in the animal genome concurrent with the emergence of the Placentalia some 165,000,000 years ago.[8]

Function

[edit]Discovery of PLAC1 resulted from an examination of the region around the human hypoxanthine ribosyltransferase 1 (HPRT) gene aimed at determining whether or not a placenta-specific protein was encoded there. This question was raised because the region was believed to be involved in both placental and fetal pathologies. Once identified, PLAC1 and its mouse ortholog Plac1 were found to be expressed throughout gestation.[9][10] It was quickly established that PLAC1 expression is specific to trophoblast cells and that it is a critical element in establishing and maintaining a normal placenta. Expression was further localised to the apical region of the syncytiotrophoblast, the leading, invasive part of the developing embryo.[11] PLAC1 expression terminates at the onset of labor and PLAC1 mRNAs clear the peripheral maternal circulatory system soon after delivery.[12][13][14]

Recognition that PLAC1 plays an important role in first establishing the placenta and, subsequently, in maintaining it throughout gestation leads to the idea that PLAC1 may play a role in gestational issues from infertility to premature birth. An important contribution to this idea is the observation that a Plac1 knockout mouse model exhibited both placentomegaly in the dams and growth restriction in the pups.[6][15] Numerous human gestational issues have been associated with abnormal PLAC1 expression including intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR),[16][17][18] premature birth,[19][20] implantation failure,[21][22][23][24] and preeclampsia.[25][26][27][28][29][30][31] Several of these studies have sought to develop PLAC1 assays into diagnostic tools with mixed success.

Cancer

[edit]While it has been clearly established that PLAC1 is truly placenta-specific, almost from the outset it was also clear that PLAC1 is co-opted in human cancers. The first evidence that PLAC1 is co-opted in cancer was published in 2006.[32] Since then, PLAC1 expression has been demonstrated in more than a dozen human cancers and in at least one hundred human cancer cell lines. Among the cancers in which PLAC1 expression is evident are gastric cancers,[33][34][35] colon/colorectal cancers,[35][36][37] liver cancers,[38][39] pancreatic cancers,[40] lung cancers,[41] and breast cancers.[42][43][44][45][46][47] In nearly all cases, PLAC1 expression is associated with poor clinical outcomes. Nowhere is this more true than in cancers of the male and female reproductive tract. That is, prostate cancer,[48][49] uterine cancer,[50] ovarian cancer[51][52] and cervical cancer[53] all have demonstrated a positive correlation between PLAC1 expression and prognosis.

In 2005, PLAC1 expression in differentiating fibroblasts was shown to be regulated by fibroblast growth factor 7 (FGF7).[54] This regulatory relationship has since been shown to be central to Akt Serine/Threonine kinase 1-mediated cancer cell proliferation.[55] PLAC1 forms a cell surface complex with FGF7 and the FGFR2IIIb receptor which then activates a cascade leading to Akt phosphorylation. Expression of PLAC1is, in turn, partially determined by the p53 tumor suppressor.[56] PLAC1 expression is suppressed by wild-type p53 but increases in the presence of mutated or absent p53.[52]

Immunotherapy

[edit]PLAC1 is classified as a “cancer-testis antigen” as it is preferentially expressed in trophoblasts and tumors. In addition to results associating PLAC1 expression with risk of various cancers as well as with prognosis, the ability of PLAC1 to elicit an immune response suggests that its specificity could be harnessed therapeutically. One group in particular is pioneering the potential.[57] Using anti-PLAC1/drug conjugates they have shown that PLAC1-based immunotherapy is highly promising.[48][49]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000170965 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000061082 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ Chen Y, Moradin A, Schlessinger D, Nagaraja R (November 2011). "RXRα and LXR activate two promoters in placenta- and tumor-specific expression of PLAC1". Placenta. 32 (11): 877–884. doi:10.1016/j.placenta.2011.08.011. PMC 3210379. PMID 21937108.

- ^ a b Jackman SM, Kong X, Fant ME (August 2012). "Plac1 (placenta-specific 1) is essential for normal placental and embryonic development". Molecular Reproduction and Development. 79 (8): 564–572. doi:10.1002/mrd.22062. PMC 4594876. PMID 22729990.

- ^ Devor EJ (2014). "Placenta-specific protein 1 is conserved throughout the Placentalia under purifying selection". TheScientificWorldJournal. 2014: 537356. doi:10.1155/2014/537356. PMC 4142310. PMID 25180201.

- ^ Devor EJ (2016). "Placenta-specific protein 1 (PLAC1) is a unique onco-fetal-placental protein and an underappreciated therapeutic target in cancer". Integrative Cancer Science and Therapeutics. 3 (3): 479–483. doi:10.15761/ICST.1000192.

- ^ Chang WL, Wang H, Cui L, Peng NN, Fan X, Xue LQ, et al. (September 2016). "PLAC1 is involved in human trophoblast syncytialization". Reproductive Biology. 16 (3): 218–224. doi:10.1016/j.repbio.2016.07.001. PMID 27692364.

- ^ Massabbal E, Parveen S, Weisoly DL, Nelson DM, Smith SD, Fant M (July 2005). "PLAC1 expression increases during trophoblast differentiation: evidence for regulatory interactions with the fibroblast growth factor-7 (FGF-7) axis". Molecular Reproduction and Development. 71 (3): 299–304. doi:10.1002/mrd.20272. PMID 15803460.

- ^ Chang WL, Yang Q, Zhang H, Lin HY, Zhou Z, Lu X, et al. (October 2014). "Role of placenta-specific protein 1 in trophoblast invasion and migration". Reproduction. 148 (4): 343–352. doi:10.1530/REP-14-0052. PMID 24989904.

- ^ Fant M, Weisoly DL, Cocchia M, Huber R, Khan S, Lunt T, et al. (December 2002). "PLAC1, a trophoblast-specific gene, is expressed throughout pregnancy in the human placenta and modulated by keratinocyte growth factor". Molecular Reproduction and Development. 63 (4): 430–436. doi:10.1002/mrd.10200. PMID 12412044.

- ^ Rawn SM, Cross JC (2008). "The evolution, regulation, and function of placenta-specific genes". Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology. 24: 159–181. doi:10.1146/annurev.cellbio.24.110707.175418. PMID 18616428.

- ^ Concu M, Banzola I, Farina A, Sekizawa A, Rizzo N, Marini M, et al. (2005). "Rapid clearance of mRNA for PLAC1 gene in maternal blood after delivery". Fetal Diagnosis and Therapy. 20 (1): 27–30. doi:10.1159/000081365. PMID 15608456.

- ^ Fant ME, Fuentes J, Kong X, Jackman S (2014). "The nexus of prematurity, birth defects, and intrauterine growth restriction: a role for plac1-regulated pathways". Frontiers in Pediatrics. 2: 8. doi:10.3389/fped.2014.00008. PMC 3930911. PMID 24600606.

- ^ Deyssenroth MA, Li Q, Lacasaña M, Nomura Y, Marsit C, Chen J (October 2017). "Expression of placental regulatory genes is associated with fetal growth". Journal of Perinatal Medicine. 45 (7): 887–893. doi:10.1515/jpm-2017-0064. PMC 5630498. PMID 28675750.

- ^ Coy DH, Kastin AJ, Plotnikoff NP (1978). "[Biological studies with enkephalins and endorphins and their analogs]". Annales de l'Anesthesiologie Francaise. 19 (5): 373–378. PMID 29532.

- ^ Ibanoglu MC, Ozgu-Erdinc AS, Kara O, Topcu HO, Uygur D (October 2019). "Association of Higher Maternal Serum Levels of Plac1 Protein with Intrauterine Growth Restriction". Zeitschrift Fur Geburtshilfe und Neonatologie. 223 (5): 285–288. doi:10.1055/a-0743-7403. PMID 30267394.

- ^ Farina A, Rizzo N, Concu M, Banzola I, Sekizawa A, Grotti S, et al. (January 2005). "Lower maternal PLAC1 mRNA in pregnancies complicated with vaginal bleeding (threatened abortion <20 weeks) and a surviving fetus". Clinical Chemistry. 51 (1): 224–227. doi:10.1373/clinchem.2004.041228. PMID 15516331.

- ^ Rizzo N, Banzola I, Concu M, Morano D, Sekizawa A, Giommi F, et al. (June 2007). "PLAC1 mRNA levels in maternal blood at induction of labor correlate negatively with induction-delivery interval". European Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Biology. 132 (2): 177–181. doi:10.1016/j.ejogrb.2006.05.039. PMID 16860456.

- ^ Kotto-Kome AC, Silva C, Whiteman V, Kong X, Fant ME (2011). "Circulating Anti-PLAC1 Antibodies during Pregnancy and in Women with Reproductive Failure: A Preliminary Analysis". International Scholarly Research Notice. 2011 (1): 530491.

- ^ Matteo M, Greco P, Levi Setti PE, Morenghi E, De Rosario F, Massenzio F, et al. (April 2013). "Preliminary evidence for high anti-PLAC1 antibody levels in infertile patients with repeated unexplained implantation failure". Placenta. 34 (4): 335–339. doi:10.1016/j.placenta.2013.01.006. hdl:11369/188745. PMID 23434395.

- ^ Shi LY, Ma Y, Zhu GY, Liu JW, Zhou CX, Chen LJ, et al. (October 2018). "Placenta-specific 1 regulates oocyte meiosis and fertilization through furin". FASEB Journal. 32 (10): 5483–5494. doi:10.1096/fj.201700922RR. PMID 29723063.

- ^ Yilmaz N, Timur H, Ugurlu EN, Yilmaz S, Ozgu-Erdinc AS, Erkilinc S, et al. (August 2020). "Placenta specific protein-1 in recurrent pregnancy loss and in In Vitro Fertilisation failure: a prospective observational case-control study". Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 40 (6): 843–848. doi:10.1080/01443615.2019.1674263. PMID 31791163.

- ^ Fujito N, Samura O, Miharu N, Tanigawa M, Hyodo M, Kudo Y (March 2006). "Increased plasma mRNAs of placenta-specific 1 (PLAC1) and glial cells-missing 1 (GCM1) in mothers with pre-eclampsia". Hiroshima Journal of Medical Sciences. 55 (1): 9–15. PMID 16594548.

- ^ Purwosunu Y, Sekizawa A, Farina A, Wibowo N, Okazaki S, Nakamura M, et al. (August 2007). "Cell-free mRNA concentrations of CRH, PLAC1, and selectin-P are increased in the plasma of pregnant women with preeclampsia". Prenatal Diagnosis. 27 (8): 772–777. doi:10.1002/pd.1780. PMID 17554801.

- ^ Kodama M, Miyoshi H, Fujito N, Samura O, Kudo Y (April 2011). "Plasma mRNA concentrations of placenta-specific 1 (PLAC1) and pregnancy associated plasma protein A (PAPP-A) are higher in early-onset than late-onset pre-eclampsia". The Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Research. 37 (4): 313–318. doi:10.1111/j.1447-0756.2010.01349.x. PMID 21392164.

- ^ Zanello M, Sekizawa A, Purwosunu Y, Curti A, Farina A (2014). "Circulating mRNA for the PLAC1 gene as a second trimester marker (14-18 weeks' gestation) in the screening for late preeclampsia". Fetal Diagnosis and Therapy. 36 (3): 196–201. doi:10.1159/000360854. PMID 25138310.

- ^ Ibanoglu MC, Ozgu-Erdinc AS, Uygur D (2018). "Maternal placi protein levels in early- and late-onset preeclampsia". Ginekologia Polska. 89 (3): 147–152. doi:10.5603/GP.a2018.0025. PMID 29664550.

- ^ Wan L, Sun D, Xie J, Du M, Wang P, Wang M, et al. (November 2019). "Declined placental PLAC1 expression is involved in preeclampsia". Medicine. 98 (44): e17676. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000017676. PMC 6946281. PMID 31689783.

- ^ Levine L, Habertheuer A, Ram C, Korutla L, Schwartz N, Hu RW, et al. (April 2020). "Syncytiotrophoblast extracellular microvesicle profiles in maternal circulation for noninvasive diagnosis of preeclampsia". Scientific Reports. 10 (1): 6398. Bibcode:2020NatSR..10.6398L. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-62193-7. PMC 7156695. PMID 32286341.

- ^ Chen J, Pang XW, Liu FF, Dong XY, Wang HC, Wang S, et al. (April 2006). "[PLAC1/CP1 gene expression and autologous humoral immunity in gastric cancer patients]". Beijing da Xue Xue Bao. Yi Xue Ban = Journal of Peking University. Health Sciences. 38 (2): 124–127. PMID 16617350.

- ^ Otsubo T, Akiyama Y, Hashimoto Y, Shimada S, Goto K, Yuasa Y (January 2011). "MicroRNA-126 inhibits SOX2 expression and contributes to gastric carcinogenesis". PLOS ONE. 6 (1): e16617. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...616617O. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0016617. PMC 3029394. PMID 21304604.

- ^ Liu W, Zhai M, Wu Z, Qi Y, Wu Y, Dai C, et al. (June 2012). "Identification of a novel HLA-A2-restricted cytotoxic T lymphocyte epitope from cancer-testis antigen PLAC1 in breast cancer". Amino Acids. 42 (6): 2257–2265. doi:10.1007/s00726-011-0966-3. PMID 21710262.

- ^ a b Liu FF, Shen DH, Wang S, Ye YJ, Song QJ (December 2010). "[Expression of PLAC1/CP1 genes in primary colorectal carcinoma and its clinical significance]". Zhonghua Bing Li Xue Za Zhi = Chinese Journal of Pathology. 39 (12): 810–813. PMID 21215095.

- ^ Liu F, Zhang H, Shen D, Wang S, Ye Y, Chen H, et al. (March 2014). "Identification of two new HLA-A*0201-restricted cytotoxic T lymphocyte epitopes from colorectal carcinoma-associated antigen PLAC1/CP1". Journal of Gastroenterology. 49 (3): 419–426. doi:10.1007/s00535-013-0811-4. PMID 23604623.

- ^ Liu F, Shen D, Kang X, Zhang C, Song Q (November 2015). "New tumour antigen PLAC1/CP1, a potentially useful prognostic marker and immunotherapy target for gastric adenocarcinoma". Journal of Clinical Pathology. 68 (11): 913–916. doi:10.1136/jclinpath-2015-202978. PMID 26157147.

- ^ Guo L, Xu D, Lu Y, Peng J, Jiang L (November 2017). "Detection of circulating tumor cells by reverse transcription‑quantitative polymerase chain reaction and magnetic activated cell sorting in the peripheral blood of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma". Molecular Medicine Reports. 16 (5): 5894–5900. doi:10.3892/mmr.2017.7372. PMC 5865766. PMID 28849093.

- ^ Wu Y, Lin X, Di X, Chen Y, Zhao H, Wang X (January 2017). "Oncogenic function of Plac1 on the proliferation and metastasis in hepatocellular carcinoma cells". Oncology Reports. 37 (1): 465–473. doi:10.3892/or.2016.5272. PMID 27878289.

- ^ Yin Y, Zhu X, Huang S, Zheng J, Zhang M, Kong W, et al. (June 2017). "Expression and clinical significance of placenta-specific 1 in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma". Tumour Biology. 39 (6): 1010428317699131. doi:10.1177/1010428317699131. PMID 28618924.

- ^ Yang L, Zha TQ, He X, Chen L, Zhu Q, Wu WB, et al. (January 2018). "Placenta-specific protein 1 promotes cell proliferation and invasion in non-small cell lung cancer". Oncology Reports. 39 (1): 53–60. doi:10.3892/or.2017.6086. PMC 5783604. PMID 29138842.

- ^ Koslowski M, Sahin U, Mitnacht-Kraus R, Seitz G, Huber C, Türeci O (October 2007). "A placenta-specific gene ectopically activated in many human cancers is essentially involved in malignant cell processes". Cancer Research. 67 (19): 9528–9534. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1350. PMID 17909063.

- ^ Koslowski M, Türeci O, Biesterfeld S, Seitz G, Huber C, Sahin U (October 2009). "Selective activation of trophoblast-specific PLAC1 in breast cancer by CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein beta (C/EBPbeta) isoform 2". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 284 (42): 28607–28615. doi:10.1074/jbc.M109.031120. PMC 2781404. PMID 19652226.

- ^ Wagner M, Koslowski M, Paret C, Schmidt M, Türeci O, Sahin U (December 2013). "NCOA3 is a selective co-activator of estrogen receptor α-mediated transactivation of PLAC1 in MCF-7 breast cancer cells". BMC Cancer. 13: 570. doi:10.1186/1471-2407-13-570. PMC 4235021. PMID 24304549.

- ^ Li Q, Liu M, Wu M, Zhou X, Wang S, Hu Y, et al. (April 2018). "PLAC1-specific TCR-engineered T cells mediate antigen-specific antitumor effects in breast cancer". Oncology Letters. 15 (4): 5924–5932. doi:10.3892/ol.2018.8075. PMC 5844056. PMID 29556312.

- ^ Li Y, Chu J, Li J, Feng W, Yang F, Wang Y, et al. (August 2018). "Cancer/testis antigen-Plac1 promotes invasion and metastasis of breast cancer through Furin/NICD/PTEN signaling pathway". Molecular Oncology. 12 (8): 1233–1248. doi:10.1002/1878-0261.12311. PMC 6068355. PMID 29704427.

- ^ Yuan H, Chen V, Boisvert M, Isaacs C, Glazer RI (2018). "PLAC1 as a serum biomarker for breast cancer". PLOS ONE. 13 (2): e0192106. Bibcode:2018PLoSO..1392106Y. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0192106. PMC 5809008. PMID 29432428.

- ^ a b Ghods R, Ghahremani MH, Madjd Z, Asgari M, Abolhasani M, Tavasoli S, et al. (December 2014). "High placenta-specific 1/low prostate-specific antigen expression pattern in high-grade prostate adenocarcinoma". Cancer Immunology, Immunotherapy. 63 (12): 1319–1327. doi:10.1007/s00262-014-1594-z. PMC 11029513. PMID 25186610.

- ^ a b Nejadmoghaddam MR, Zarnani AH, Ghahremanzadeh R, Ghods R, Mahmoudian J, Yousefi M, et al. (October 2017). "Placenta-specific1 (PLAC1) is a potential target for antibody-drug conjugate-based prostate cancer immunotherapy". Scientific Reports. 7 (1): 13373. Bibcode:2017NatSR...713373N. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-13682-9. PMC 5645454. PMID 29042604.

- ^ Devor EJ, Leslie KK (2013). "The oncoplacental gene placenta-specific protein 1 is highly expressed in endometrial tumors and cell lines". Obstetrics and Gynecology International. 2013: 807849. doi:10.1155/2013/807849. PMC 3723095. PMID 23935632.

- ^ Tchabo NE, Mhawech-Fauceglia P, Caballero OL, Villella J, Beck AF, Miliotto AJ, et al. (August 2009). "Expression and serum immunoreactivity of developmentally restricted differentiation antigens in epithelial ovarian cancer". Cancer Immunity. 9: 6. PMC 2935768. PMID 19705800.

- ^ a b Devor EJ, Gonzalez-Bosquet J, Warrier A, Reyes HD, Ibik NV, Schickling BM, et al. (May 2017). "p53 mutation status is a primary determinant of placenta-specific protein 1 expression in serous ovarian cancers". International Journal of Oncology. 50 (5): 1721–1728. doi:10.3892/ijo.2017.3931. PMC 5403493. PMID 28339050.

- ^ Devor EJ, Reyes HD, Gonzalez-Bosquet J, Warrier A, Kenzie SA, Ibik NV, et al. (May 2017). "Placenta-Specific Protein 1 Expression in Human Papillomavirus 16/18-Positive Cervical Cancers Is Associated With Tumor Histology". International Journal of Gynecological Cancer. 27 (4): 784–790. doi:10.1097/IGC.0000000000000957. PMC 5405019. PMID 28375929.

- ^ Massabbal E, Parveen S, Weisoly DL, Nelson DM, Smith SD, Fant M (July 2005). "PLAC1 expression increases during trophoblast differentiation: evidence for regulatory interactions with the fibroblast growth factor-7 (FGF-7) axis". Molecular Reproduction and Development. 71 (3): 299–304. doi:10.1002/mrd.20272. PMID 15803460.

- ^ Roldán DB, Grimmler M, Hartmann C, Hubich-Rau S, Beißert T, Paret C, et al. (May 2020). "PLAC1 is essential for FGF7/FGFRIIIb-induced Akt-mediated cancer cell proliferation". Oncotarget. 11 (20): 1862–1875. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.27582. PMC 7244013. PMID 32499871.

- ^ Chen Y, Schlessinger D, Nagaraja R (September 2013). "T antigen transformation reveals Tp53/RB-dependent route to PLAC1 transcription activation in primary fibroblasts". Oncogenesis. 2 (9): e67. doi:10.1038/oncsis.2013.31. PMC 3816221. PMID 23999628.

- ^ Mahmoudian J, Nazari M, Ghods R, Jeddi-Tehrani M, Ostad SN, Ghahremani MH, et al. (2020). "Expression of Human Placenta-specific 1 (PLAC1) in CHO-K1 Cells". Avicenna Journal of Medical Biotechnology. 12 (1): 24–31. PMC 7035464. PMID 32153735.

External links

[edit]Further reading

[edit]- Fant M, Weisoly DL, Cocchia M, Huber R, Khan S, Lunt T, et al. (December 2002). "PLAC1, a trophoblast-specific gene, is expressed throughout pregnancy in the human placenta and modulated by keratinocyte growth factor". Molecular Reproduction and Development. 63 (4): 430–436. doi:10.1002/mrd.10200. PMID 12412044. S2CID 11298991.

- Strausberg RL, Feingold EA, Grouse LH, Derge JG, Klausner RD, Collins FS, et al. (December 2002). "Generation and initial analysis of more than 15,000 full-length human and mouse cDNA sequences". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 99 (26): 16899–16903. Bibcode:2002PNAS...9916899M. doi:10.1073/pnas.242603899. PMC 139241. PMID 12477932.

- Ota T, Suzuki Y, Nishikawa T, Otsuki T, Sugiyama T, Irie R, et al. (January 2004). "Complete sequencing and characterization of 21,243 full-length human cDNAs". Nature Genetics. 36 (1): 40–45. doi:10.1038/ng1285. PMID 14702039.

- Gerhard DS, Wagner L, Feingold EA, Shenmen CM, Grouse LH, Schuler G, et al. (October 2004). "The status, quality, and expansion of the NIH full-length cDNA project: the Mammalian Gene Collection (MGC)". Genome Research. 14 (10B): 2121–2127. doi:10.1101/gr.2596504. PMC 528928. PMID 15489334.

- Concu M, Banzola I, Farina A, Sekizawa A, Rizzo N, Marini M, et al. (2005). "Rapid clearance of mRNA for PLAC1 gene in maternal blood after delivery". Fetal Diagnosis and Therapy. 20 (1): 27–30. doi:10.1159/000081365. PMID 15608456. S2CID 46537823.

- Massabbal E, Parveen S, Weisoly DL, Nelson DM, Smith SD, Fant M (July 2005). "PLAC1 expression increases during trophoblast differentiation: evidence for regulatory interactions with the fibroblast growth factor-7 (FGF-7) axis". Molecular Reproduction and Development. 71 (3): 299–304. doi:10.1002/mrd.20272. PMID 15803460. S2CID 29069803.

- Otsuki T, Ota T, Nishikawa T, Hayashi K, Suzuki Y, Yamamoto J, et al. (2007). "Signal sequence and keyword trap in silico for selection of full-length human cDNAs encoding secretion or membrane proteins from oligo-capped cDNA libraries". DNA Research. 12 (2): 117–126. doi:10.1093/dnares/12.2.117. PMID 16303743.

- Fujito N, Samura O, Miharu N, Tanigawa M, Hyodo M, Kudo Y (March 2006). "Increased plasma mRNAs of placenta-specific 1 (PLAC1) and glial cells-missing 1 (GCM1) in mothers with pre-eclampsia". Hiroshima Journal of Medical Sciences. 55 (1): 9–15. PMID 16594548.

- Rizzo N, Banzola I, Concu M, Morano D, Sekizawa A, Giommi F, et al. (June 2007). "PLAC1 mRNA levels in maternal blood at induction of labor correlate negatively with induction-delivery interval". European Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Biology. 132 (2): 177–181. doi:10.1016/j.ejogrb.2006.05.039. PMID 16860456.

- Fant M, Barerra-Saldana H, Dubinsky W, Poindexter B, Bick R (July 2007). "The PLAC1 protein localizes to membranous compartments in the apical region of the syncytiotrophoblast". Molecular Reproduction and Development. 74 (7): 922–929. doi:10.1002/mrd.20673. PMID 17186554. S2CID 8474935.

- Purwosunu Y, Sekizawa A, Farina A, Wibowo N, Okazaki S, Nakamura M, et al. (August 2007). "Cell-free mRNA concentrations of CRH, PLAC1, and selectin-P are increased in the plasma of pregnant women with preeclampsia". Prenatal Diagnosis. 27 (8): 772–777. doi:10.1002/pd.1780. PMID 17554801. S2CID 12589177.

- Koslowski M, Sahin U, Mitnacht-Kraus R, Seitz G, Huber C, Türeci O (October 2007). "A placenta-specific gene ectopically activated in many human cancers is essentially involved in malignant cell processes". Cancer Research. 67 (19): 9528–9534. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1350. PMID 17909063.