| Murder of Jo Cox | |

|---|---|

| Location | Market street, Birstall, West Yorkshire, England |

| Coordinates | 53°43′53″N 1°39′40″W / 53.7315°N 1.66098°W |

| Date | 16 June 2016 c. 12:53 p.m. (BST) |

Attack type | Shooting, stabbing |

| Weapons | Firearm, knife |

| Deaths | 1 (Jo Cox) |

| Injured | 1 (Bernard Carter-Kenny) |

| Perpetrator | Thomas Mair |

| Motive | Cox's support for the European Union and immigration[1] |

On 16 June 2016, Jo Cox, the British Labour Party Member of Parliament for Batley and Spen, died after being shot and stabbed multiple times in Birstall, West Yorkshire, England, shortly before she was due to hold a constituency surgery. A Scottish-born 52-year-old local man named Thomas Alexander Mair was arrested in connection with Cox's death. On 23 November 2016, Mair was found guilty of murder and other offences connected to the killing. He was sentenced to life imprisonment with a whole life order.[2][3]

Cox was singled out for attack as a "passionate defender" of the European Union and immigration. Mair viewed the Labour MP as "one of 'the collaborators' [and] a traitor" to white people.[1]

The incident was the first killing of a sitting British MP since the death of Conservative MP Ian Gow, who was murdered in a Provisional Irish Republican Army terrorist attack in 1990, and the first death of a politician during an attack since Andrew Pennington, a county councillor, was killed in 2000 while defending Liberal Democrat MP Nigel Jones.

Victim

Helen Joanne "Jo" Cox (née Leadbeater); was elected to represent the Batley and Spen parliamentary seat at the 2015 general election, having spent several years working for the international humanitarian charity Oxfam.[4][5]

Born in Batley, West Yorkshire, Cox was a student at Pembroke College, Cambridge, and graduated from the University of Cambridge with a degree in Social and Political Sciences in 1995. After working as a political assistant to the Labour MP Joan Walley, and later for MEP Glenys Kinnock, she joined Oxfam in 2002, rising to become head of policy and advocacy at Oxfam GB. She was selected to contest the Batley and Spen seat after the previous incumbent decided not to stand in 2015. Having doubled Labour's majority for the seat to 6,051, she became a campaigner on issues relating to the Syrian Civil War and founded and chaired the all-party parliamentary group Friends of Syria.[4][5]

Cox was married to Brendan Cox. They had two children, who were aged three and five at the time of her death.[6]

Following Cox's death on 16 June 2016, West Yorkshire Coroner Martin Fleming opened an inquest at Bradford Coroner's Court on 24 June. After hearing that a postmortem had identified the preliminary cause of death as resulting from "multiple stab and gunshot wounds", Fleming adjourned the six-minute hearing, releasing Cox's body to allow her family to make funeral arrangements.[7][8] The funeral, "a very small and private family affair",[9] was held in her constituency on 15 July and many thousands of people paid their respects as the cortege passed.[10]

Attack

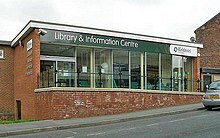

Around 1:00 p.m. on 16 June 2016, after leaving her car on Market Street, Birstall, West Yorkshire to go to the library where she had been scheduled to attend a constituency event, Cox was attacked by Thomas Mair.[11] He was armed with a knife and a firearm, variously described as "old or makeshift" and "probably an old sawn-off shotgun".[12][13] At trial the firearm was identified as a .22 calibre Weihrauch bolt-action rifle that had had most of its stock and barrel cut-down, its overall length was around 12 inches.[14]

Retired mines rescuer Bernard Carter-Kenny, age 77, was waiting for his wife outside the library and recognised Cox. He witnessed the assailant stab Cox, who fell to the ground, before shooting her and stabbing her again. Carter-Kenny intervened, rushing to stop the attack, and suffered a stab wound to the abdomen as he tried to tackle the man.[11][15][16][17][18] Carter-Kenny was able to retreat to a nearby sandwich shop.[11] The attacker left the scene, but was pursued by an eyewitness, Darren Playford, who followed him and telephoned police to describe his location.[19] Armed police officers attended the incident, and arrested a suspect.[20]

At 1:48 p.m. Cox was pronounced dead by a doctor working with the paramedic crew attending.[21]

Perpetrator

Thomas Alexander Mair (born 12 August 1963 in Kilmarnock, Scotland) was the elder of two sons of Mary, a factory worker, and James Mair, a machine operator in the lace industry. After Mair's parents divorced, he, his brother and their mother moved to Birstall, a mill town 8 miles (13 km) south-west of Leeds, before his mother married again and had another son.[1] Mair lived in Birstall for at least forty years and exhibited traits of obsessive-compulsive disorder. However, he was examined by a psychiatrist after his arrest who could find no evidence of mental problems that could have caused his actions. He believed liberals, leftists and the mainstream media to be the cause of the world's problems.[1] Mair was a frequent user of his local library's computers, where he researched subjects such as the BNP, white supremacism, Nazism, the KKK, Waffen SS, Israel, public shootings, serial killers and matricide, as well as the Wikipedia pages of MPs William Hague and Ian Gow (who was killed by a Provisional IRA car-bomb).[1] Mair was particularly fascinated by Norwegian far-right terrorist Anders Behring Breivik, and kept newspaper clippings from the Daily Mail about the case.[22] Detective Superintendent Nick Wallen from West Yorkshire Police described Mair as a "loner in the truest sense of the word ... who never held down a job, never had a girlfriend [and] never [had] any friends".[1]

Although he had links with the National Front in the 1990s, and was recently seen at an EDL rally, both anti-fascists and supporters of various far-right organisations deny that Mair had ever "crossed their radar". Despite the presence of several fringe far-right groups in West Yorkshire and his identification with extremist political figures, Mair appeared to have made little effort to make contact or involvement with local individuals or groups of a like mind.[1] Todd Blodgett, an American former far-right activist, told the SPLC that in May 2000 (when Blodgett was working as a paid informant for the FBI), Mair attended a gathering of American white supremacists in London that was convened by National Alliance head William Luther Pierce and arranged by another member of the British far-right, Mark Cotterill.[23][24] According to Blodgett, the group of 15 to 20 people included Stephen Cartwright and Richard Barnbrook, and the group discussed how to expand American white power music (such as that promoted by Resistance Records, which Pierce had recently purchased) into Europe. Blodgett described Mair as quiet, self-educated, well-mannered, and loosely affiliated with the Leeds chapter of the National Alliance. According to Blodgett, Mair expressed racist and antisemitic views, was a Holocaust denier, and admired the neo-Nazi band Skrewdriver.[23][24]

According to The Daily Telegraph, a January 2006 blog post attributed to the group described Mair as "one of the earliest subscribers and supporters of SA Patriot",[25] a far-right, pro-apartheid publication (renamed SA Patriot in Exile in 1991), and published at least two letters in the publication in the years 1991–1999. Mair wrote to the organisation in 1991 saying that:

I was most impressed by your publication and the insight it gives into the South African scene ... Meanwhile, you might be interested to know that the British media's propaganda offensive against South Africa continues relentlessly. Almost every "news" bulletin contains one item about South Africa which, needless to say, never fails to present Whites in the worse [sic] possible light ... The nationalist movement in the UK also continues to fight on against the odds. The murders of George Seawright and John McMichael in Ulster are an extreme example of what we are up against. Despite everything I still have faith that the White Race will prevail, both in Britain and in South Africa, but I fear that it's going to be a very long and very bloody struggle.

— Mair in 1991[26]

In 1999, Mair wrote to the publication. In his letter, he spoke out against "'collaborators' in the White South African population" who were opposed to apartheid, saying that:

It was heartening to see that you are still carrying on the struggle ... I was glad you strongly condemned "collaborators" in the White South African population. In my opinion the greatest enemy of the old Apartheid system was not the ANC and the Black masses but White liberals and traitors.

— Mair in 1999[26]

In 2006 the magazine's online newsletter asked for information on Mair's address as "recent correspondence sent to him was being returned".[27] Following Mair's arrest, the SA Patriot said:

It is true that a Mr Thomas A. Mair from Batley in Yorkshire subscribed to our magazine S.A Patriot when we were still published in South Africa itself. We can confirm therefore that we have never met Mr Mair, and apart from brief contact way back in the mid-1980s when he briefly subscribed to our magazine we have had no contact with him. All attempts to try to link him to our magazine during more recent years are therefore completely without foundation.[27]

Mair also bought literature from the Springbok Club. Alan Harvey, editor of its official magazine, told The Guardian that Mair sent the group £5, "which would have been enough for about five issues".[1]

The Guardian referred to Mair as "an extremely low burner" who "appears to have fantasised about killing a 'collaborator' for more than 17 years, drawing inspiration from" David Copeland.[1] Copeland, a diagnosed paranoid schizophrenic and admirer of William Luther Pierce (head of the National Alliance) was a source of great inspiration to Mair when he bombed Black British, South Asian and LGBT populations on a 13-day campaign in 1999 in the hope of triggering a race war within the United Kingdom. Three died and more than 140 were injured, many losing limbs. Copeland was arrested shortly after this final bombing of the Admiral Duncan.[28][29] Ten days after Copeland's first court appearance, a consignment of goods from the National Alliance headquarters in the United States were sent to Mair's home. According to a packing slip obtained by the Southern Poverty Law Center, Mair had bought numerous items from the organisation, including: manuals on the manufacturing of bombs and homemade pistols; 6 copies of Free Speech, a publication of the National Alliance; and a copy of Ich Kämpfe. Over the course of four years, he began to subscribe to Free Speech as well as Secret of the Runes and We Get Confessions. The SPLC released receipts showing that Mair had spent more than $620 buying publications from National Vanguard Books in the years 1993–2003, including works on how to make improvised weapons.[25][30]

In 2010, Mair attended Pathways Day Services for adults with mental health problems. He then began doing voluntary work and told the Huddersfield Daily Examiner that volunteering had improved his mental health, saying: "it has done me more good than all the psychotherapy and medication in the world".[31] The evening before killing Jo Cox, Mair, then an unemployed gardener,[32] visited an alternative therapy centre in Birstall seeking treatment for depression; he was told to return the next day for an appointment.[33] However, Mair's health was not part of the defence case in the trial.[34] After his arrest, he was examined by a psychiatrist who could find no evidence that he was not responsible for his actions due to his mental health.[1]

Cox was singled out for attack as a "passionate defender" of the European Union and immigration. Mair viewed the Labour MP as "one of 'the collaborators' [and] a traitor" to white people.[1]

Investigation

The investigation revealed overwhelming evidence against Mair, including CCTV footage of the attack.[32] The investigation also revealed that Mair was motivated by extreme right-wing beliefs.[32]

Police said that Cox was the victim of an "isolated but targeted" attack.[35] A special police unit that searched Mair's home[36] found Nazi regalia and far-right books.[32][37] Above Mair's bookshelf was a swastika and Reichsadler,[37] as well information on how to construct bombs and explosives.[1][25]

Mair had made Nazi and white supremacist-related internet searches, evidence of these was introduced at his trial: "Examination of his browsing history revealed that he had been searching for material about the British National Party, apartheid, the Ku Klux Klan, prominent Jewish people, Israel and matricide."[32][37]

Trial, conviction, and sentence

On 18 June, police announced that Mair had been charged with murder, grievous bodily harm, possession of a firearm with intent to commit an indictable offence and possession of an offensive weapon.[38] The same day, he appeared before Westminster Magistrates' Court and when asked to confirm his name said, "My name is death to traitors, freedom for Britain." He was asked to repeat what he had said, and did so;[38][39] he also refused to give his age or address.[40] His lawyers confirmed his name as Thomas Mair, and said there was no indication of what plea would be given. He was remanded in custody at Belmarsh Prison. Emma Arbuthnot, the Deputy Chief Magistrate presiding at the hearing added, "Bearing in mind the name he has just given, he ought to be seen by a psychiatrist."[38][39]

On 20 June, a bail hearing took place at the Central Criminal Court of England and Wales, the Old Bailey.[40] Mair appeared by video link from Belmarsh Prison and spoke only to confirm his name as Thomas Mair. His lawyer said that Mair would not apply for bail, and the judge, Mr Justice Sweeney, remanded him in custody until a hearing to be held "under terrorism-related protocols" before Mr Justice Saunders.[41][42] At that hearing, on 23 June, a provisional trial date was scheduled for 14 November, a preliminary hearing for 19 September and a plea hearing on 4 October.[43] Saunders said the case would be handled as part of "the terrorism case management list" on which cases related to terrorism (as defined by the Terrorism Act 2000) are placed.[43]

At the September 2016 hearing, Mair's counsel said the defence would not advance a diminished responsibility argument based on medical evidence.[44] At the hearing on 4 October 2016, Mair (appearing by video link) spoke to confirm his name but refused to enter a plea, prompting the judge, Mr Justice Wilkie, to enter not-guilty pleas on his behalf.[44][45]

Mair's trial began at the Old Bailey on 14 November 2016.[46] He made no attempt to defend himself during the seven-day trial.[32] The court heard testimony that during the attack, Mair had cried out "This is for Britain" as well as "keep Britain independent" and "Put Britain first";[32][47][48][49] however, Britain First leader Paul Golding denied any connection with the murder, saying that his organisation "would not condone actions like that". Describing the actions as "disgusting and "an outrage", Golding added: "I hope the person who carried out this heinous crime will get what he deserves".[27]

On 23 November 2016, Mair was convicted of Cox's murder, grievous bodily harm against Bernard Carter-Kenny, who was stabbed by Mair after trying to aid Cox, possession of a firearm with intent, and possession of a dagger.[32][50] The jury took about 90 minutes to reach its verdict.[32]

The same day, Mr Justice Wilkie sentenced Mair to life imprisonment. Wilkie said he had no doubt that Mair murdered Cox for the purpose of advancing a political, racial and ideological cause, namely that of violent white supremacism and exclusive nationalism most associated with Nazism and its modern forms. This made the case one of exceptionally high seriousness and accordingly he imposed a whole life term, meaning Mair would not become eligible for parole.[3]

Reactions

To the murder

United Kingdom

Cox's husband Brendan issued a statement on 16 June, the day of her death, which said:

Today is the beginning of a new chapter in our lives. More difficult, more painful, less joyful, less full of love. I and Jo's friends and family are going to work every moment of our lives to love and nurture our kids and to fight against the hate that killed Jo. Jo believed in a better world and she fought for it every day of her life with an energy, and a zest for life that would exhaust most people. She would have wanted two things above all else to happen now, one that our precious children are bathed in love and two, that we all unite to fight against the hatred that killed her. Hate doesn't have a creed, race or religion, it is poisonous. Jo would have no regrets about her life, she lived every day of it to the full.[51]

The statement was described by Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn as "one of the most moving statements I've ever heard from somebody so recently bereaved."[52] In a later interview, broadcast by the BBC on 21 June, Brendan Cox said of his wife:

She was a politician and she had very strong political views and I believe she was killed because of those views. ... I think she died because of them and she would want to stand up for those in death as much as she did in life.[53]

Following the death, flags were flown at half-mast at British public buildings, including the Palace of Westminster, Buckingham Palace, and 10 Downing Street.[30] It was announced that the Queen would write a private letter of condolence to Cox's widower.[54] The counting of votes at the Tooting by-election, held on the day Cox died, was halted for a two-minute silence.[55]

Corbyn stated that "The whole of the Labour Party and Labour family – and indeed the whole country – will be in shock at the horrific murder of Jo Cox today" and paid tribute to a "wonderful woman".[56] A vigil was held in Parliament Square attended by senior politicians in the Labour party including Corbyn. First Minister of Scotland Nicola Sturgeon described the news as "utterly shocking and tragic news, which has left everyone stunned".[57] Chief Minister of Gibraltar Fabian Picardo stated: "This is a truly appalling attack on a serving MP working hard to serve her community. This horrific act is an attack on democracy and the British freedoms that Jo Cox worked so diligently and passionately to defend."[58] Rosena Allin-Khan, who won the Tooting by-election for Labour, used her victory speech to pay tribute to Cox: "Jo’s death reminds us that our democracy is precious but fragile. We must never forget to cherish it."[55] Prime Minister David Cameron and Corbyn made a joint visit to Birstall the day after the attack, where they joined locals to lay floral tributes to Cox.[59] Cameron said:

The most profound thing that has happened is that two children have lost their mother, a loving husband has lost a loving wife, and parliament has lost one of its most passionate and brilliant campaigners, someone who epitomised the fact that politics is about serving others.[60]

Veteran Labour politician Neil Kinnock, whose wife Glenys had supported Cox's candidacy and whose son Stephen shared an office with her, described the family's grief in a BBC television interview.[61] Writing for the Financial Times, Sarah Brown, who worked with Cox on a campaign to reduce the number of deaths in pregnancy and childbirth said: "Jo’s life testified to her view that tolerance is not enough. We must tackle the causes of prejudice and discrimination, teach ourselves how to treat others equally and do far more to help those most in need."[62] Cox was remembered at church services held on Sunday 19 June, including one held at St Peter's Church, Birstall, where Rev. Paul Knight described her as a "fervent advocate for the poor and the oppressed".[63]

On 17 June, friends of Cox established a fund in her memory, with proceeds to be split between three non-profit groups: Hope not Hate (anti-extremism), Royal Voluntary Service (benefiting the elderly) and the White Helmets (Syrian volunteer search-and-rescue workers). The fund raised over £500,000 in one day,[64] and £1 million had been raised by 20 June.[65] Significant donations to the Jo Cox Fund included an award of £375,000 raised from fines resulting from the Libor banking scandal.[66] Proceeds from a cover of the 1979 Bette Midler song "The Rose", recorded and released by Batley Community Choir, will also benefit the fund.[67]

Friends organised "More in Common – Celebrating the life of Jo Cox", a public event for people to remember Cox, scheduled to take place in Trafalgar Square, London on 22 June, the date of her 42nd birthday.[63] The London event saw Cox's family transported on a memorial boat laden with floral tributes along the River Thames to Westminster where crowds listened to speakers, who included Brendan Cox, Malala Yousafzai, Bono, Bill Nighy and Gillian Anderson; similar events took place in locations around the world, including Batley and Spen, Auckland, Paris, Washington D.C. and Buenos Aires.[68][69] On 20 June, Oxfam announced that it would release Stand As One – Live at Glastonbury 2016, an album of live performances from the 2016 Glastonbury Festival in memory of Cox; proceeds from the album, released on 11 July, will go towards helping the charity's work with refugees.[70][71] Musicians and festivalgoers at Glastonbury, held later that week, also paid tribute to Cox; at one concert Billy Bragg led the audience in a rendition of "We Shall Overcome" and was joined on stage by women wearing suffragette ribbons.[72]

Parliament was recalled on Monday 20 June to allow MPs to pay tribute to Cox.[73] In a break from convention (under which MPs sit grouped together by party), MPs considered whether to sit together on a non-party basis for the memorial sitting, a suggestion made by Conservative MP Jason McCartney.[74][75] Only a few MPs chose to do so, however.[76] Following the sitting of Parliament, MPs and others attended a memorial service at nearby St Margaret's Church.[77] On 20 June a petition was created calling for Bernard Carter-Kenny, who had intervened in the attack, to be awarded the George Cross.[78] He was awarded the George Medal in the 2017 Birthday Honours.[79][80] Carter-Kenny died of cancer on 14 August 2017.[81][82]

In July 2016, organisers of the annual Tolpuddle Martyrs' Festival, an event in Dorset celebrating the efforts of a group of agricultural workers to form a trade union, dedicated that year's event to Cox's memory.[83] In August, cyclists took part in the Jo Cox Way, a five-day 260 mile cycle ride from West Yorkshire to Westminster to raise money for charities supported by Cox.[84][85] The event raised £1,500.[86] At its 2016 party conference, held in Liverpool in September, Labour launched the Jo Cox Women in Leadership Programme, a mentoring scheme designed to help women into leadership roles, and facilitated by the Labour Women's Network.[87] In November 2016, MPs and musicians collaborated on a version of The Rolling Stones song "You Can't Always Get What You Want" for release as a charity single in Cox's memory, and to raise funds for the launch of the Jo Cox Foundation.[88] Artists who took part in the recording include Ricky Wilson of Kaiser Chiefs, Steve Harley, KT Tunstall and David Gray.[89] Sir Mick Jagger and Keith Richards subsequently announced they would be waiving their royalties from sales of the single.[90] BBC Two aired the documentary Jo Cox: Death of An MP on 13 June 2017 to coincide with the first anniversary of her murder.[91] Also in June 2017, and to mark the first anniversary of Cox's death, her family and friends urged people to take part in a weekend of events to celebrate her life and held under the banner of "The Great Get Together"; events included picnics, street parties and concerts.[92] The Great Get Together was also supported by four former British Prime Ministers–John Major, Tony Blair, Gordon Brown and David Cameron–who recorded a joint video paying tribute to Cox and urging people to celebrate her life. The video was aired as part of the late night Channel 4 talk show The Last Leg on the eve of the first anniversary of her death.[93] On 24 June 2017, a coat of arms designed by Cox's children was unveiled by them at the House of Commons, where MPs killed in office are remembered by heraldic shields.[94] Rock group U2 paid tribute to Cox during the UK leg of their 2017 Joshua Tree Tour; lead vocalist Bono, who had worked with her on the Make Poverty History campaign, dedicated the song "Ultraviolet (Light My Way)" to her memory.[95]

International

Senior politicians from around the world paid tribute to Cox and expressed shock at her death. United States President Barack Obama telephoned Cox's husband to offer condolences on behalf of the American people,[96] and invited the family to meet him at the White House; the meeting took place in September after Brendan Cox attended a refugee summit in New York.[97] Former U.S. Representative Gabrielle Giffords of Arizona, who was seriously injured in a shooting in 2011, stated that she was "Absolutely sickened to hear of the assassination of Jo Cox. She was young, courageous, and hardworking. A rising star, mother, and wife."[98][99] Several European leaders expressed their shock at the news, among them German Chancellor Angela Merkel, who described the attack as "terrible" and called for a moderation of language to counter radicalisation and to foster respect.[100] Overseas politicians who knew Cox personally included New Zealand Labour MP Phil Twyford, who remarked that "Jo will be sorely missed by her family, her friends, UK politics and the international Labour movement."[101] In the Canadian House of Commons, Nathan Cullen, an NDP MP who had known Cox for several years, described her in an emotional tribute as "a dedicated Labour MP and a long advocate of human rights in Britain and around the world".[102] Numerous other tributes were paid to Cox, including from public figures in Australia,[103] Canada,[102][104] Czech Republic,[105] Finland,[106] France,[57] Greece,[107] Ireland,[107][108] Italy,[100] Netherlands,[109] New Zealand,[101][110][111] the PLO,[112] Spain,[58] Sweden[113] and the United States.[114][115]

In July 2016, the Italian Parliament established the Cox Committee, a cross-party committee on intolerance, xenophobia, racism and hate crime, naming it in honour of Cox.[116] In August, her nomination of the Syrian Civil Defense for the 2016 Nobel Peace Prize was accepted by the Nobel Committee. Cox had written to the Committee earlier in the year praising the work of the civilian voluntary emergency rescue organisation known as the White Helmets, and nominating them for the prize. The nomination gained the support of twenty of her fellow MPs, as well as a dozen or so high-profile personalities including George Clooney, Daniel Craig, Chris Martin and Michael Palin. The nomination was also supported by members of Canada's New Democratic Party, who urged Stéphane Dion, the country's Foreign Affairs Minister, to give his backing on behalf of Canada.[117][118]

To the conviction of Mair

In a statement to the BBC following the conviction of Mair, Cox’s widower Brendan stated that he felt only pity for Mair, and expressed hope "that Jo’s death will have meaning" in persuading people "that we hold more in common than that which divides us."[119]

In The Times, David Aaronovitch asked why "some people – all of them pro-Brexit as it happens" were "so keen to dismiss the first (and accurate) reports of Mair's words?", claiming that such people "resisted because deep down they feared that aspects of the language or direction of the Brexit campaign they legitimately supported had emboldened extremism. While they themselves were in no way permissive of the act, might they in some way have been permissive of the motive? Or even of the mood?". In his article, Aaronovitch cited official Home Office figures regarding a rise in race hate crime.[120] Aaronovitch's words were criticised by Peter Hitchens in the Mail On Sunday, who wrote: "let no Leftist propagandist try to smear me as an apologist for her killer ... But I am repelled and disturbed by the attempt to pretend that this deranged, muttering creep was in any way encouraged or licensed to kill a defenceless, brave young mother, by the campaign to leave the European Union".[121]

Only two British newspapers failed to feature a picture of Cox on their front pages as her murderer was arrested: the Financial Times (who instead focused on the first autumn statement from the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Philip Hammond) and the Daily Mail. The Mail was criticised for its focus on Mair's mental health and thoughts of matricide as opposed to his extremist political motivations.[122] Owen Jones tweeted that "The coverage of Michael Adebowale – one of Lee Rigby's killers – did not focus on his history of mental illness. It focused on his ideology."[123] The Mail also relegated its coverage of Mair's conviction to page 30 of its print edition, which prompted LBC radio presenter James O'Brien to accuse the paper of double standards, saying that the Mail "has chosen to put the murder by a neo-Nazi of a serving British MP ... on page 30. I don't really understand why. Unless a murder by a neo-Nazi is less offensive to the sensibilities of the editor of this newspaper than a murder by a radical Islamist."[124][125] The focus the Mail gave to the conspiracy theory that Mair "may have murdered MP Jo Cox because he feared losing his home of 40 years to an immigrant family" led to the paper being accused by Jane Matrinson in The Guardian of normalising anti-immigrant prejudice, which she saw as a factor in Cox's murder.[122]

Wider context

Cox's death was the first killing of a sitting British MP since Eastbourne MP Ian Gow was killed by the Provisional Irish Republican Army in 1990,[126][127][128] and the first serious assault since Stephen Timms was stabbed by Roshonara Choudhry in an attempted assassination in 2010.[129][130] Another example of an attack on an MP while carrying out constituency duties was the attack on Nigel Jones in 2000, resulting in the death of his assistant, local councillor Andrew Pennington.[131]

Many MPs went ahead with planned constituency surgeries scheduled on the day after Cox's death with increased security.[132] A spokeswoman for the National Police Chiefs' Council said that police forces had been asked to remind MPs to be vigilant about their personal safety: "Officers will offer further guidance and advice where an MP requests it on a case-by-case basis depending on any specific threat or risk".[133] MPs also received advice from the party whips' offices urging them to discuss security measures with their local police forces.[132]

In July 2016 Kevin McKeever, a Labour politician and partner in Portland Communications, a public relations firm accused of playing an instrumental role in an attempt to force the resignation of Jeremy Corbyn received an alleged death threat telling him he should "prepare to be coxed".[134] Commenting on the incident, and others in which MPs had received threats, Ruth Price, Cox's parliamentary assistant, urged people to "move away from the baseless, nasty and intimidating abuse MPs currently face".[135] Jo Cox's murder was also explicitly referenced in the social media posts of a man who was jailed for four months in April 2017 for making death threats towards the then MP for Eastbourne Caroline Ansell of the Conservative party.[136] Two months after the death of Jo Cox at least 25 MPs received identical death threats, including the Labour MP Chris Bryant. Bryant noted that the threats were "particularly disturbing ... [in] that a lot of these threats are to women. I think women MPs, gay MPs, ethnic minority MPs get the brunt of it”.[137]

At the time of Cox's death, MPs wishing to make additional security arrangements were required to make an application to the Independent Parliamentary Standards Authority (IPSA), the watchdog overseeing their expenses. On 20 July, the House of Commons Estimates Committee voted to strip IPSA of this responsibility amid concerns over the timeframe of the process.[138] MPs were offered training sessions in Krav Maga, a form of unarmed combat that combines judo, jujitsu, boxing and street fighting used by the Israeli intelligence agency Mossad, as a self-defence technique. The Yorkshire Post reported that the first session, held in early August, was attended by two MPs and eighteen assistants.[139]

Cox's murder took place a week before the 2016 European Union membership referendum on 23 June. The rival official campaigns suspended their activities as a mark of respect.[140] David Cameron cancelled a rally in Gibraltar supporting British EU membership.[141] Campaigning resumed on Sunday 19 June.[142][143] Polling officials in the Yorkshire and Humber region halted counting of the referendum ballots on the evening of 23 June to observe a minute's silence.[144] Election campaigning was also suspended for an hour on 21 May 2017, as politicians held a truce in memory of Cox ahead of the 2017 general election.[145]

Following Cox's murder, the Conservative Party, Liberal Democrats, UK Independence Party and the Green Party all announced they would not contest the ensuing by-election in her constituency as a mark of respect;[146] Brendan Cox also ruled out standing for the seat.[147] Tracy Brabin was chosen as Labour's candidate on 23 September,[148] and elected to the seat on 20 October.[149] Nine other candidates contested the seat.[150] They included three candidates who stated their intention to stand before the election was confirmed. On 20 June, Jack Buckby, a former member of the British National Party announced he would be a candidate in the by-election for Liberty GB.[151] On 18 July, the English Democrats announced that their deputy chair, Therese Hirst, would stand as a candidate.[152] Although UKIP did not contest the election, UKIP member Waqas Ali Khan announced on 6 August he would stand as an independent.[153]

In the days after Cox's death, Arron Banks, a businessman and founder of Leave.EU, campaigning for Britain's withdrawal from the European Union, conducted private polling to determine whether the incident would affect the referendum's outcome. After disclosing the matter to LBC radio presenter Iain Dale he was challenged as to whether such a poll was tasteless, but rejected the suggestion: "We were hoping to see what the effect of the event was. That is an interesting point of view, whether it would shift public opinion...I don't see it as very controversial."[154] Likewise, Gary Jones of the Mirror pressurised political editor Nigel Nelson to write a front-page Mirror story on "the Jo effect", claiming that her death had swung support to Remain in a new opinion poll under the headline: "Tragic Jo's Death Sparks Poll Surge" despite only 192 of the 2,046 answers ComRes received were after the murder, and that ComRes said that "the figures should be treated with a degree of caution given the sample size".[155]

At a speech to the London School of Economics in September, Martin Schulz, the President of the European Parliament cited the "nasty" referendum debate as being a contributing factor in Cox's death. The comments were swiftly criticised by some of Cox's colleagues, including leading Eurosceptic Conservative politician Jacob Rees-Mogg, who described them as "trivialising" her death.[156]

Cox's killing has been likened to that of Swedish politician Anna Lindh in 2003.[157] Lindh was stabbed to death shortly before Sweden's referendum on joining the Euro, which she supported. Campaigning was also suspended after her killing.[158] Swedish newspaper Dagens Nyheter noted: "Like Jo Cox, Anna Lindh was a young, successful politician, and both were the mothers of two children. Both were also participating in campaigns for the EU when they were murdered".[159]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Cobain, Ian; Parveen, Nazia; Taylor, Matthew (23 November 2016). "The slow-burning hatred that led Thomas Mair to murder Jo Cox". The Guardian. Retrieved 24 November 2016.

- ^ "Man guilty of murdering MP Jo Cox". BBC News. 23 November 2016. Retrieved 23 November 2016.

- ^ a b Mr Justice Wilkie (23 November 2016). "R v Thomas Mair: Sentencing Remarks of Mr Justice Wilkie" (PDF). Courts and Tribunals Judiciary. Retrieved 24 November 2016.

- ^ a b "Jo Cox obituary: Proud Yorkshire lass who became local MP". BBC News. BBC. 16 June 2016. Retrieved 23 June 2016.

- ^ a b "Jo Cox obituary". The Guardian. Guardian Media Group. 16 June 2016. Retrieved 23 June 2016.

- ^ "MP Jo Cox killed in appalling street attack". SKY News. 16 June 2016. Retrieved 16 June 2016.

- ^ Parveen, Nazia (24 June 2016). "Body of MP Jo Cox released to family for funeral". The Guardian. Guardian Media Group. Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- ^ "MP Jo Cox died from 'multiple stab and gunshot wounds'". BBC News. BBC. 24 June 2016. Retrieved 25 June 2016.

- ^ "Jo Cox funeral will be small and private affair, say family". The Guardian. Guardian Media Group. 11 July 2016. Retrieved 12 July 2016.

- ^ Pidd, Helen (15 July 2016). "Jo Cox funeral brings thousands of mourners on to streets". The Guardian. Retrieved 15 July 2016.

- ^ a b c "Jo Cox murder suspect tells court his name is 'death to traitors, freedom for Britain'". The Guardian. 18 June 2016. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- ^ "British Lawmaker Jo Cox Dies After Attack". 16 June 2016. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ^ Telegraph Video (16 June 2016). "Eyewitness describes 'enraged' Jo Cox gunman". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- ^ Chandler, Mark (15 November 2016). "Jo Cox trial: Thomas Mair 'used homemade gun and knife to murder MP'". London Evening Standard. Retrieved 19 November 2016.

- ^ Flynn, Alexis (18 June 2016). "Suspect Charged With Murder in Jo Cox Case Appears in Court". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- ^ Holden, Michael; Faulconbridge, Guy (18 June 2016). "Jo Cox murder suspect says name is 'Death to traitors, freedom for Britain'". Reuters. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- ^ Yorke, Harry; Evans, Martin (17 June 2016). "Retired miner who tried to tackle Jo Cox's attacker was also hero of colliery disaster". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- ^ "Man who attempted to save Jo Cox is mine rescue service veteran". The Guardian. 18 June 2016. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- ^ Cobain, Ian (17 November 2016). "Jo Cox killer walked away calmly after brutal attack, court told". The Guardian. Retrieved 23 November 2016.

- ^ Booth, Robert; Dodd, Vikram; Parveen, Nazia; Pidd, Helen (17 June 2016). "Jo Cox: grief and shock over death of 'Labour MP with huge compassion'". The Guardian. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- ^ "Death of Batley and Spen MP Jo Cox – West Yorkshire Police". West Yorkshire Police. 20 June 2016. Retrieved 8 August 2016.

- ^ "Neo-Nazi terrorist Thomas Mair given whole life term for Jo Cox murder". TELL MAMA. 23 November 2016.

- ^ a b Stelloh, Tim (19 June 2016). "Thomas Mair, Suspect in Murder of UK Lawmaker Jo Cox, Attended White Supremacy Meeting: Report". NBC News. Retrieved 20 June 2016.

- ^ a b Potok, Mark (19 June 2016). "Accused British Assassin Thomas Mair Attended Racists' 2000 Meeting". Southern Poverty Law Center. Retrieved 20 June 2016.

- ^ a b c Hatewatch Staff. "Alleged killer of British MP was a longtime supporter of the neo-Nazi National Alliance". Southern Poverty Law Center.

- ^ a b Amend, Alex (20 June 2016). "Here Are the Letters Thomas Mair Published in a Pro-Apartheid Magazine". Southern Poverty Law Center.

- ^ a b c "Who Is Tommy Mair? Man Arrested Over Jo Cox Murder Linked To Far-Right Groups". Huffington Post. 17 June 2016. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- ^ "The Nailbomber", BBC Panorama, 30 June 2000. Transcript.

- ^ Hopkins, Nick; Hall, Sarah (30 June 2000). "David Copeland: a quiet introvert, obsessed with Hitler and bombs". The Guardian.

- ^ a b Castle, Stephen (17 June 2016). "Thomas Mair, Suspect in Jo Cox Killing, Had History of Neo-Nazi Ties and Mental Illness". The New York Times. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ^ "Jo Cox killing: Who is suspect Tommy Mair?". The Irish Times. 17 June 2016. Retrieved 20 June 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Cobain, Ian; Taylor, Matthew (23 November 2016). "Far-right terrorist Thomas Mair jailed for life for Jo Cox murder". The Guardian. Retrieved 25 November 2016.

- ^ "Jo Cox murder: Thomas Mair asked for mental health treatment day before MP died". The Daily Telegraph. 17 June 2016. Retrieved 20 June 2016.

- ^ "Jo Cox: No medical evidence to be heard in murder trial". BBC News. 19 September 2016. Retrieved 19 September 2016.

- ^ Dewan, Angela; Karimi, Faith; Sterling, Joe (17 June 2016). "Police charge man with murder of British lawmaker". CNN. Retrieved 25 November 2016.

- ^ "Jo Cox killing: Nazi regalia discovered at house of suspect". The Guardian. 17 June 2016. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ^ a b c Cobain, Ian (21 November 2016). "Jo Cox murder suspect collected far-right books, court hears". The Guardian. Retrieved 25 November 2016.

- ^ a b c Booth, Robert (18 June 2016). "Jo Cox murder suspect tells court his name is 'death to traitors, freedom for Britain'". The Guardian. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- ^ a b "Jo Cox MP death: Thomas Mair in court on murder charge". BBC News. 18 June 2016. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- ^ a b Sawer, Patrick; Hughes, Laura; Mendick, Robert; Heighton, Luke (18 June 2016). "Jo Cox's sister calls her 'perfect' and 'utterly amazing' as accused murderer tells court his name is 'Death to traitors, freedom for Britain'". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 19 June 2016.

- ^ Walker, Peter (20 June 2016). "Jo Cox killing: Thomas Mair to face judge under terrorism protocols". The Guardian. Retrieved 20 June 2016.

- ^ "Jo Cox MP death: Thomas Mair appears at Old Bailey". BBC News. 20 June 2016. Retrieved 20 June 2016.

- ^ a b Dodd, Vikram (23 June 2016). "Thomas Mair to go on trial in autumn accused of Jo Cox murder". The Guardian. Guardian Media Group. Retrieved 23 June 2016.

- ^ a b Holden, Michael (4 October 2016). "Not-guilty pleas entered for man accused of killing MP Jo Cox". Reuters. Retrieved 4 October 2016.

- ^ "Jo Cox MP death: Murder accused Thomas Mair refuses to enter pleas". BBC News. 4 October 2016. Retrieved 4 October 2016.

- ^ "Labour MP Jo Cox 'murdered for political cause'". BBC News. 14 November 2016. Retrieved 14 November 2016.

- ^ "Jo Cox MP dead after shooting attack". BBC News. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ^ "Jo Cox MP death: Eyewitness heard man shouting". BBC News. 16 June 2016. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ^ Laville, Sandra; Parveen, Nazia; Pidd, Helen; Booth, Robert (16 June 2016). "Jo Cox attack: shots, screams and sadness outside a West Yorkshire library". The Guardian. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ^ "Man guilty of murdering MP Jo Cox". BBC News. 23 November 2016. Retrieved 23 November 2016.

- ^ "Jo Cox dead: Read husband Brendan Cox's statement in full". The Independent. 16 June 2016. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ^ "Jo Cox Remembered At Vigils In Parliament Square, Birstall And At Her Houseboat On The Thames". Huffington Post. 16 June 2016. Retrieved 21 June 2016.

- ^ "Jo Cox 'died for her views', her widower tells BBC". BBC News. 21 June 2016. Retrieved 21 June 2016.

- ^ O'Leary, Elisabeth; Sandle, Paul (17 June 2016). "Britain mourns murdered lawmaker, EU referendum campaign suspended". Reuters. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ^ a b Quinn, Ben (17 June 2016). "Labour's Rosena Allin-Khan holds Tooting in by-election". The Guardian. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ^ "Politicians pay tribute to 'great star' Jo Cox". BBC News. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ^ a b "Reaction to the killing of British lawmaker Jo Cox". Reuters. 17 June 2016. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ^ a b "Spain and Gibraltar condemn murder of British MP Jo Cox". 17 June 2016. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ^ Parveen, Nazia; Pidd, Helen (17 June 2016). "Cameron and Corbyn join in grief for Jo Cox, an 'exceptional woman killed by hatred'". The Guardian. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ^ Mason, Rowena; Booth, Robert; Dodd, Vikram (17 June 2016). "Jo Cox killed by 'well of hatred', says Jeremy Corbyn". The Guardian. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- ^ "Jo Cox MP: Lord Kinnock mourns 'death in the family'". BBC News. 17 June 2016. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- ^ Brown, Sarah (17 June 2016). "Jo Cox lived by example, and so should we". Financial Times. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|subscription=ignored (|url-access=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "Jo Cox MP remembered as '21st Century Good Samaritan'". BBC News. 19 June 2016. Retrieved 19 June 2016.

- ^ Slawson, Nicola (18 June 2016). "Jo Cox charity fund passes £500,000 target in a day". The Guardian. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- ^ "Memorial Fund For MP Jo Cox Reaches £1m". Sky News. British Sky Broadcasting. 20 June 2016. Retrieved 16 July 2016.

- ^ "Jo Cox: Libor fines donated to Batley and Spen MP-backed charity". BBC News. BBC. 13 July 2016. Retrieved 16 July 2016.

- ^ "Batley Community Choir release Jo Cox MP charity single". BBC News. BBC. 16 July 2016. Retrieved 16 July 2016.

- ^ "Jo Cox birthday: MP remembered at world events". BBC News. BBC. 22 June 2016. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- ^ Addley, Esther; Elgot, Jessica; Perraudin, Frances (22 June 2016). "Jo Cox: thousands pay tribute on what should have been MP's birthday". The Guardian. Guardian Media Group. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- ^ Payne, Chris (20 June 2016). "Coldplay, Muse, Chvrches & More to Tribute Jo Cox With Glastonbury Live Album". Billboard. Retrieved 21 June 2016.

- ^ "Glastonbury live album to be dedicated to Jo Cox MP". BBC News. BBC. 21 June 2016. Retrieved 21 June 2016.

- ^ Ellis-Petersen, Hannah (23 June 2016). "Billy Bragg leads tributes to MP Jo Cox at Glastonbury festival". The Guardian. Guardian Media Group. Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- ^ "Jo Cox death: MPs return to Parliament to pay tribute". BBC News. 20 June 2016. Retrieved 20 June 2016.

- ^ "MPs could mix together for Jo Cox tributes". BBC News. 19 June 2016. Retrieved 20 June 2016.

- ^ Slawson, Nicola (18 June 2016). "Rival MPs may sit together in honour of killed MP Jo Cox". The Guardian. Retrieved 20 June 2016.

- ^ Morley, Nicole (20 June 2016). "Tears for Jo Cox: MPs cry as they pay tribute in the Commons". Metro. Retrieved 20 June 2016.

- ^ "Hundreds of MPs attend prayers for Jo Cox". Premier. Retrieved 20 June 2016.

- ^ "George Cross call for Jo Cox attack 'hero' Bernard Kenny". BBC News. 20 June 2016. Retrieved 20 June 2016.

- ^ Earnshaw, Tony (16 June 2017). "Hero Bernard Kenny who tried to save Jo Cox given George Medal on anniversary of her death". Huddersfield Examiner. Trinity Mirror. Retrieved 16 June 2017.

- ^ "No. 61969". The London Gazette (8th supplement). 16 June 2017. p. 11774.

- ^ Sutcliffe, Robert (14 August 2017). "RIP our hero: Bernard Kenny who tried to save Jo Cox passes away". huddersfieldexaminer. Retrieved 14 August 2017.

- ^ "Jo Cox George Medal 'hero' Kenny dies". BBC News. 14 August 2017. Retrieved 14 August 2017.

- ^ Evans, Lettie (11 July 2016). "The Tolpuddle Martyrs' Festival 2016 in memory of MP Jo Cox". Somerset Live. Local World. Retrieved 12 July 2016.

- ^ "Cyclists ride from Yorkshire to London for Jo Cox charities". BBC News. BBC. 17 August 2016. Retrieved 19 August 2016.

- ^ Beever, Susie (17 August 2016). "From West Yorkshire to Westminster: Hundreds depart as Jo Cox Way cycle gets going in Cleckheaton". Huddersfield Examiner. Trinity Mirror Group. Retrieved 19 August 2016.

- ^ Colley, Gina (23 August 2016). "Pedal power raises £1,500 in memory of Jo Cox". Huddersfield Examiner. Trinity Mirror Group. Retrieved 23 August 2016.

- ^ "Labour launches women's mentoring scheme in memory of Jo Cox". ITV News. ITV. 25 September 2016. Retrieved 25 September 2016.

- ^ Thorpe, Vanessa (13 November 2016). "Jo Cox charity single to be recorded by politicians and pop stars". The Guardian. Guardian Media Group. Retrieved 19 November 2016.

- ^ "Jo Cox charity single brings together politicians and musicians". BBC News. BBC. 17 November 2016. Retrieved 18 November 2016.

- ^ "Rolling Stones waive Jo Cox Christmas single royalties". BBC News. BBC. 15 December 2016. Retrieved 15 December 2016.

- ^ Bains, Raj (12 June 2017). "A year on, Jo Cox: Death Of An MP sheds new light on both the murdered mother-of-two and her killer". Huddersfield Daily Examiner. Trinity Mirror. Retrieved 16 June 2017.

- ^ "Events held to remember murdered MP Jo Cox". BBC News. BBC. 16 June 2017. Retrieved 16 June 2017.

- ^ Hughes, Laura (16 June 2017). "Four former Prime Ministers unite in message of tribute to Jo Cox". The Telegraph. Telegraph Media Group. Retrieved 15 July 2017.

- ^ "Jo Cox MP honoured with Commons plaque". BBC News. BBC. 24 June 2017. Retrieved 24 June 2017.

- ^ "U2 celebrate Jo Cox on Joshua Tree tour". BBC News. BBC. 9 July 2017. Retrieved 9 July 2017.

- ^ "Obama Makes Phone Call To Jo Cox's Husband". Sky News. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- ^ Smith, David (24 September 2016). "Barack Obama meets with Jo Cox's family to pay tribute to British MP". The Guardian. Guardian Media Group. Retrieved 24 September 2016.

- ^ Chadbourn, Margaret (16 June 2016). "Gabby Giffords 'Sickened' at 'Assassination' of British Lawmaker". ABC News. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ^ "Labour MP Jo Cox dies after being shot and stabbed as husband urges people to 'fight against the hate' that killed her". The Daily Telegraph. 16 June 2016. Retrieved 16 June 2016.

- ^ a b Henley, Jon; Oltermann, Philip; Chrisafis, Angelique (17 June 2016). "Merkel urges EU in/out campaigns to moderate language after Jo Cox death". The Guardian. Guardian Media Group. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ^ a b Twyford, Phil (17 June 2016). "New Zealand Labour MP Phil Twyford's tribute to friend Jo Cox". Stuff.co.nz. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ^ a b Simons, Nedi (17 June 2016). "Jo Cox's 'Limitless Love' Praised by Emotional Canadian MP Nathan Cullen". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ^ "Malcolm Turnbull: Deeply shocked by the murder of UK MP Jo Cox. Our condolences, prayers and solidarity are with her family & the people of the UK". ABC News (Australia). 17 June 2016. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ^ "Jo Cox's death grieved by politicians in Canada, worldwide". Reuters. 16 June 2016. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ^ "Condolences of Prime Minister Sobotka to Prime Minister of the United Kingdom Cameron". Government of the Czech Republic. 17 June 2016. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- ^ "Sipilä tviittasi condolences to the British parliament". Iltalehti (in Finnish). Alma Media. 16 June 2016. Retrieved 21 June 2016.

- ^ a b Palazzo, Chiara; Akkoc, Raziye (17 June 2016). "Worldwide tributes flow in after Jo Cox MP's shocking death". The Telegraph. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ^ "Taoiseach suspends campaigning after 'appalling crime'". Irish Independent. 17 June 2016. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- ^ "Prime Minister advocates strengthening of European internal market" (in Dutch). 17 June 2016. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- ^ Price, Rosanna (17 June 2016). "Prime Minister John Key hopes anti-immigration rhetoric doesn't spark attack in New Zealand". Stuff.co.nz. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ^ Jones, Nicholas (17 June 2016). "Phil Twyford on fatal shooting of friend Jo Cox: 'It is an awful, violent thing to happen'". The New Zealand Herald. Fairfax New Zealand Ltd. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ^ Qud, Nour. "Ashrawi: Palestine mourns the loss of British Labour MP Jo Cox". Retrieved 20 June 2016.

- ^ Löfven, Stefan (16 June 2016). "Uttalande av statsminister Stefan Löfven med anledning av mordet på brittiska parlamentarikern Jo Cox". regeringen.se. Government of Sweden. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ "Kerry: Jo Cox killing is 'assault on democracy'". ITV News. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ^ "Clinton Condemns Killing of 'Rising Star' Jo Cox". Sky News. 20 June 2016. Retrieved 8 August 2016.

- ^ "Italian Parliament names hate crime committee after Jo Cox". The Scotsman. Johnston Press. 18 July 2016. Retrieved 18 July 2016.

- ^ Ensor, Josie (15 September 2016). "MP Jo Cox's heartfelt plea for Syrian 'heroes' to receive Nobel Prize shortly before her death". The Daily Telegraph. Telegraph Media Group. Retrieved 17 September 2016.

- ^ Cullen, Catherine (15 September 2016). "NDP pushes for Syrian 'White Helmets' to win Nobel Peace Prize". CBC News. CBC. Retrieved 19 September 2016.

- ^ Sewell, Chan (23 November 2016). "Right-Wing Extremist Convicted of Murdering Jo Cox, a U.K. Lawmaker". New York Times. Retrieved 27 November 2016.

- ^ Aaronovitch, David (24 November 2016). "Dog-whistle politics can be a deadly game". The Times. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|subscription=ignored (|url-access=suggested) (help) - ^ Hitchens, Peter (27 November 2016). "I want Jo's killer to hang". Mail On Sunday. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ^ a b Matrinson, Jane (24 November 2016). "Why didn't the Daily Mail put the jailing of Jo Cox's murderer on its front page?". The Guardian. Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- ^ Allegretti, Aubrey (17 June 2016). "Newsnight Interview, Daily Star Splash Prompt Row Over Jo Cox Murder Coverage". The Huffington Post.

- ^ O'Brien, James (24 November 2016). "James O'Brien's Question For The Daily Mail Goes Viral". LBC. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

- ^ Nelson, Sara C (24 November 2016). "James O'Brien Lets Rip At Daily Mail Amid Backlash Over Tabloid's Jo Cox Coverage". The Huffington Post.

- ^ Boyle, Danny; Akkoc, Raziye (17 June 2016). "Labour MP Jo Cox dies after being shot and stabbed as husband urges people to 'fight against the hate' that killed her". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ^ Calamur, Krishnadev; Vasilogambros, Matt (16 June 2016). "The Attack on a British MP". The Atlantic. Retrieved 16 June 2016.

As our colleague Matt Ford notes, Cox is the first MP to be assassinated in office since Ian Gow, a Conservative lawmaker who was killed in a car bombing by the Irish Republican Army in 1990.

- ^ Rentoul, John (16 June 2016). "Jo Cox Dead: A History of violence against MPs". Independent. Retrieved 16 June 2016.

- ^ Siddique, Haroon (16 June 2016). "Attack on Jo Cox is only the latest serious assault against an MP". The Guardian. Retrieved 16 June 2016.

- ^ Nicks, Denver (16 June 2016). "Assassinated British MP Was a Vocal Humanitarian". Time. Retrieved 16 June 2016.

- ^ "MP's killing raises questions about security". BBC News. 16 June 2016. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ^ a b "Police urge MPs to review security after Jo Cox attack". BBC News. 17 June 2016. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ^ Laville, Sandra; Asthana, Anushka (17 June 2016). "Police contact MPs to advise on security after Jo Cox killing". The Guardian. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ^ "Worker at PR firm allegedly behind Labour coup plot 'receives death threat'". The Guardian. 5 July 2016.

- ^ Perraudin, Frances (12 July 2016). "Jo Cox's former assistant urges Labour to stand up to 'nasty' MP abuses". The Guardian. Guardian Media Group. Retrieved 12 July 2016.

- ^ "Man jailed for threatening to kill Caroline Ansell MP". BBC News. 12 April 2017. Retrieved 12 April 2017.

- ^ "MPs receive identical death threats over weekend". The Guardian. 30 August 2016.

- ^ "MPs to be offered extra security after Jo Cox's death". BBC News. BBC. 19 July 2016. Retrieved 20 July 2016.

- ^ "Free combat lessons for MPS after Jo Cox killing". Yorkshire Evening Post. Johnston Press. 14 August 2016. Retrieved 14 August 2016.

- ^ "EU Referendum campaigns remain suspended after Jo Cox attack". BBC News. 17 June 2016. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ^ "British PM David Cameron cuts short Gibraltar visit over MP attack". The Straits Times. Singapore Press Holdings. 16 June 2016. Retrieved 21 May 2017.

- ^ Stewart, Heather (18 June 2016). "Paused EU referendum debate to resume, but with a more respectful tone". The Guardian. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- ^ "David Cameron: 'No turning back' on EU vote". BBC News. 19 June 2016. Retrieved 19 June 2016.

- ^ "Counting stops for minute silence for Jo Cox". The Telegraph. 24 June 2016. Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- ^ "General election campaign paused to remember MP Jo Cox". BBC News. BBC. 21 May 2017. Retrieved 21 May 2017.

- ^ Stone, Jon (17 June 2016). "Jo Cox death: Parties stand down in killed Labour MP's seat as Corbyn and Cameron call for unity". The Independent. Independent Print Limited. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ^ Withnall, Adam (21 June 2016). "Jo Cox 'died for her political views', says husband Brendan Cox in first interview". The Independence. Independent Print Limited. Retrieved 21 June 2016.

- ^ "Soap star Tracy Brabin to stand in Jo Cox by-election". BBC News. BBC. 23 September 2016. Retrieved 23 September 2016.

- ^ "Batley and Spen by-election: Tracy Brabin victory for 'hope and unity'". BBC News. BBC. 21 October 2016. Retrieved 22 October 2016.

- ^ "Ten candidates standing for election in Jo Cox constituency". ITV News. ITV. 27 September 2016. Retrieved 29 September 2016.

- ^ Cowburn, Ashley (20 June 2016). "Jo Cox: Liberty GB move to contest Labour MP's former seat branded 'obscene' and 'contemptible'". The Independent. Independent Print Limited. Retrieved 9 July 2016.

- ^ Booth, Phil (18 July 2016). "English Democrats to contest by-election for Jo Cox's Batley & Spen seat with "pro-leave" candidate". Huddersfield Daily Examiner. Trinity Mirror. Retrieved 18 July 2016.

- ^ Glover, Chloe (5 August 2016). "UKIP member to stand as independent in Batley and Spen by-election". Huddersfield Daily Examiner. Retrieved 6 August 2016.

- ^ Syal, Rajeev (20 June 2016). "Leave.EU donor defends polling on effect of Jo Cox killing". The Guardian. Guardian Media Group. Retrieved 9 July 2016.

- ^ "Street of Shame". Private Eye. No. 1421. Pressdram Ltd. 24 June 2016. p. 6.

- ^ Hughes, Laura (23 September 2016). "EU chief Martin Schulz blames Jo Cox death on 'nasty' referendum". The Daily Telegraph. Telegraph Media Group. Retrieved 23 September 2016.

- ^ "Swedish politician's death 13 years ago mirrors murder of UK lawmaker". CNBC. 17 June 2016. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- ^ Moore, Charles (19 June 2016). "The killing of Jo Cox does not justify suspending democratic debate over the EU". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- ^ "Worldwide tributes flow in after Jo Cox MP's shocking death". The Daily Telegraph. 17 June 2016. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

External links

![]() Media related to Death of Jo Cox at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Death of Jo Cox at Wikimedia Commons