In the renewable energy sector, a dunkelflaute (German: [ˈdʊŋkəlˌflaʊtə] ⓘ, lit. 'dark doldrums' or 'dark wind lull', plural dunkelflauten)[1] is a period of time in which little or no energy can be generated with wind and solar power, because there is neither wind nor sunlight.[2][3][4] In meteorology, this is known as anticyclonic gloom.[5]

Meteorology[edit]

Unlike a typical anticyclone, dunkelflauten are associated not with clear skies, but with very dense cloud cover (0.7–0.9), consisting of stratus, stratocumulus, and fog.[6] As of 2022[update] there is no agreed quantitative definition of dunkelflaute.[7] Li et al. define it as wind and solar both below 20% of capacity during a particular 60-minute period.[8] High albedo of low-level stratocumulus clouds in particular – sometimes the cloud base height is just 400 meters – can reduce solar irradiation by half.[6]

In the north of Europe, dunkelflauten originate from a static high-pressure system that causes an extremely weak wind combined with overcast weather with stratus or stratocumulus clouds.[9] There are 2–10 dunkelflaute events per year.[10] Most of these events occur from October to February; typically 50 to 150 hours per year, a single event usually lasts up to 24 hours.[11]

In Japan, on the other hand, dunkelflauten are seen in summer and winter. The former is caused by stationary fronts in early summer and autumn rainy seasons (called Baiu and Akisame, respectively),[12] while the latter is caused by arrivals of south-coast cyclones.[13]

Renewable energy effects[edit]

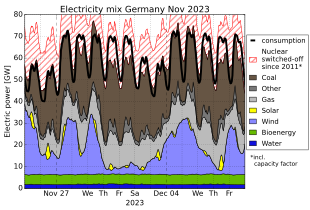

These periods are a big issue in energy infrastructure if a significant amount of electricity is generated by solar and wind power.[14][1][15] Dunkelflauten can occur simultaneously over a very large region, but are less correlated between geographically distant regions, so multi-national power grid schemes can be helpful.[16] Events that last more than two days over most of Europe happen about every five years.[17] To ensure power during such periods flexible energy sources may be used, energy may be imported, and demand may be adjusted.[18][19]

For alternative energy sources, countries use fossil fuels (coal, oil and natural gas), hydroelectricity or nuclear power and, less often, energy storage to prevent power outages.[20][21][8][22] Long-term solutions include designing electricity markets to incentivise clean flexible power.[19] A group of countries is following on from Mission Innovation to work together to solve the problem in a clean, low-carbon way by 2030, including looking into carbon capture and storage and the hydrogen economy as possible parts of the solution.[23]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b "When the wind goes, gas fills in the gap | Q1 2021 Quarterly Report". Electric Insights. 24 May 2021. Retrieved 29 June 2021.

- ^ "Dark doldrums: When wind and sun take a break". en-former.com. 31 July 2018. Retrieved 27 May 2021.

- ^ Matsuo, Yuhji; Endo, Seiya; Nagatomi, Yu; Shibata, Yoshiaki; Komiyama, Ryoichi; Fujii, Yasumasa (1 June 2020). "Investigating the economics of the power sector under high penetration of variable renewable energies". Applied Energy. 267: 113956. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2019.113956. ISSN 0306-2619. S2CID 216301290.

- ^ Ohba, Masamichi; Kanno, Yuki; Nohara, Daisuke (8 December 2021). "Climatology of dark doldrums in Japan". Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. 155: 111927. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2021.111927. S2CID 245067748.

- ^ Li et al. 2021, p. 2.

- ^ a b Li et al. 2021, p. 7.

- ^ "Was ist die Dunkelflaute? | Definition" [What are the Dark Doldrums?]. next-kraftwerke.de (in German). Retrieved 13 December 2022.

- ^ a b Li, Bowen; Basu, Sukanta; Watson, Simon J.; Russchenberg, Herman W. J. (2020). "Mesoscale modeling of a "Dunkelflaute" event". Wind Energy. 24 (1): 5–23. doi:10.1002/we.2554. ISSN 1095-4244.

- ^ Li et al. 2021, p. 6.

- ^ Li et al. 2021, p. 11.

- ^ Li et al. 2021, p. 1.

- ^ Ohba, Masamichi; Kanno, Yuki; Nohara, Daisuke (8 December 2021). "Climatology of dark doldrums in Japan". Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. 155: 111927. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2021.111927. S2CID 245067748.

- ^ Ohba, Masamichi; Kanno, Yuki; Shigeru, Bando (21 January 2023). "Effects of meteorological and climatological factors on extremely high residual load and possible future changes". Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. 175: 113188. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2023.113188.

- ^ Walker, Tamsin (8 February 2017). "What happens with German renewables in the dead of winter?". Deutsche Welle. Archived from the original on 9 February 2017. Retrieved 28 May 2021.

- ^ Ohba, Masamichi; Kanno, Yuki; Shigeru, Bando (21 January 2023). "Effects of meteorological and climatological factors on extremely high residual load and possible future changes". Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. 175: 113188. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2023.113188.

- ^ Li et al. 2021, p. 9.

- ^ McDonnell, Tim (13 December 2022). "Can Europe survive the dreaded dunkelflaute?". Quartz. Retrieved 1 February 2023.

- ^ Modelling 2050: Electricity System Analysis (PDF) (Report). Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy. December 2020. Retrieved 12 December 2023.

- ^ a b "The dreaded Dunkelflaute is no reason to slow UK's energy push". Financial Times. 13 December 2022. Retrieved 13 December 2022.

- ^ Kosowski, Kai; Diercks, Frank (2021). "Quo Vadis, Grid Stability?" (PDF). Atw. 66 (2): 16–26. ISSN 1431-5254.

- ^ Ernst, Damien. "Big infrastructures for fighting climate change" (PDF). Université de Liège.

- ^ Abbott, Malcolm; Cohen, Bruce (2020). "Issues associated with the possible contribution of battery energy storage in ensuring a stable electricity system". The Electricity Journal. 33 (6): 106771. doi:10.1016/j.tej.2020.106771. ISSN 1040-6190. S2CID 218966955.

- ^ Harrabin, Roger (2 June 2021). "Major project aims to clear clean energy hurdle". BBC News. Retrieved 3 June 2021.

Sources[edit]

- Li, Bowen; Basu, Sukanta; Watson, Simon J.; Russchenberg, Herman W. J. (11 October 2021). "A Brief Climatology of Dunkelflaute Events over and Surrounding the North and Baltic Sea Areas" (PDF). Energies. 14 (20): 6508. doi:10.3390/en14206508. eISSN 1996-1073.

Well, that’s interesting to know that Psilotum nudum are known as whisk ferns. Psilotum nudum is the commoner species of the two. While the P. flaccidum is a rare species and is found in the tropical islands. Both the species are usually epiphytic in habit and grow upon tree ferns. These species may also be terrestrial and grow in humus or in the crevices of the rocks.

View the detailed Guide of Psilotum nudum: Detailed Study Of Psilotum Nudum (Whisk Fern), Classification, Anatomy, Reproduction