Turandurey (1806 - ?) was a Wiradjuri woman from the Lachlan River area in central New South Wales near where the town of Hillston is now located. Turandurey is noted for her work as a guide and interpreter to the explorer Thomas Mitchell, while at the same time caring for her daughter Ballandella.[1]

Guide for Thomas Mitchell's expedition[edit]

Mitchell's Third Expedition began on 17 March 1836, setting out from Mount Canobolas with the Wiradjuri interpreter John Piper, who obtained a wife, Kitty, at Lake Cargelligo.[1] However, on crossing the Lachlan River valley in what is now the Central West region of NSW, Piper had difficulty connecting with local men, who appeared to be reluctant to make contact.[1]

However, Turandurey, a local woman aged around 30 seemed happy to come forward.[2] It seems that because, as a woman, she was not limited by any of the inter-tribal protocols that local men needed to respect.[3] A widow, she was joined by her daughter, Ballandella, who was aged four.[3]

The mission given to Mitchell was to finish surveying the lower Darling River, all the way to where it joined the Millewa, now known as the Murray River. Mitchell expressed concern about "hostile tribes", and was keen to have assistants who could guide, interpret and ensure friendly relations.[4]

Turandurey agreed to the role. Mitchell's journals show that she gave directions on routes for travel, where to find water and the best locations to make camp.[3] She also gave direction local food sources, such as freshwater mussels and root vegetables, along with cultural guidance on local customs surrounding birth and death.[1]

She appears to have displayed a great sense of humour, Mitchell appreciating her "animated and apparently eloquent manner."[5] When local men expressed fear of the explorers' sheep and horses, she laughed out loud.[6]

At a location recorded as 'Pomabil' she located, not just a water source, but also made contact with a party of local people who were on their way up from the Murrumbidgee River, communicating when the male interpreter, Piper, appeared to be stumped.[3] Mitchell refers to her as "The Widow" and came to admire her earnestness and appearance, describing her work as "extremely valuable".[1][3]

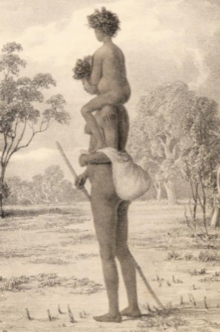

During the expedition, her daughter was badly injured during an accident with the cart, breaking her femur.[3] The infant was treated by the medical attendant John Drysdale who later applied a splint. Turandurey refused to travel on the cart, preferring to carry her injured daughter.[3][5] Mitchell was struck by how she comforted the child, with words and song that were "peculiarly soft and musical."[3][5] Mitchell established a depot on the Murrumbidgee near what is now the town of Balranald, where he left Turandurey and Ballandella to recover under the authority of his second-in-charge Granville Stapylton.[4]

Eventually they rejoined the main group and travelled all the way to Port Phillip with Mitchell's expedition, and even there was seen to be conversant with local woman, probably Wurundjeri or Bunurong.[5] Ballandella eventually made a recovery and, at that point, Turandurey expressed a desire to return to her country.[3]

She became particularly homesick on crossing the Loddon River to what is now the interior of Victoria, and made up her mind to return.[2] She was given shirts, food and a tomahawk, which she planned to use to make a canoe for Ballandella to cross the Murray River; and on departing she cried.[5] However, Turandurey quickly returned, as she was confronted by hostile Indigenous men when she had made her way north.[2]

Separation from her daughter and later life[edit]

At Lake Repose, south of The Grampians, Mitchell acted on a desire to take Ballandella from Turandurey so that he could raise her in Sydney in a European fashion. With great sadness, Turandurey handed her daughter over to Mitchell, who then proceeded to journey ahead of the main group on the return leg to Sydney. Stapylton, who remained with Turandurey called the arrangement a kidnapping.[4][1]

When Stapylton's group arrived back into the colonised region on the upper Murrumbidgee, Turandurey was married off to an Indigenous man known as "King Joey", who may have been King Joe of the Wiradjuri, presented with a breast plate in 1844 at Bangaroo station, near Canowindra.[5] Turandurey does not appear in the public record after this event in 1836.[1]

Her daughter, Ballandella, was taken into the Mitchell household in Sydney where she became the playmate of his children. However, Mitchell soon had to return to England and left Ballandella in the care of medical doctor Charles Nicholson. She was baptised in 1839 and later moved to the Hawkesbury River region where she married a European labourer named Joseph Howard. She later married John Barber, a Dharug or Darkinyung man, and had five or six children. They lived at Sackville Reach with a community of around twenty Aboriginal people which later became an Aboriginal reserve. Ballandella died in December 1863.[1][5]

Legacy[edit]

Turandurey and Ballandella have streets named in their honour in the town of Balranald which is in the vicinity of Mitchell's depot camp where they remained while Ballandella recovered from her broken leg. The town of Ballendella in regional Victoria is also named after Turandurey's daughter.[1]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Biography - Turandurey - Indigenous Australia". ia.anu.edu.au. Retrieved 2024-03-12.

- ^ a b c BUCKLEY, BATMAN & MYNDIE: Echoes of the Victorian culture-clash frontier: Sounding 1: Before 1840 and Sounding 2: Dispossession At Melbourne. BookPOD. 2021-01-01. ISBN 978-0-9922904-0-5.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i The Athenaeum. J. Lection. 1838. p. 725.

- ^ a b c "Three Expeditions into the Interior V2". gutenberg.net.au. Retrieved 2024-03-12.

- ^ a b c d e f g Cadzow, Allison, "Turandurey (c. 1806–?)", Australian Dictionary of Biography, Canberra: National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, retrieved 2024-03-12

- ^ Shellam, Tiffany; Nugent, Maria; Konishi, Shino; Cadzow, Allison, eds. (2016). Brokers and boundaries : colonial exploration in indigenous territory (PDF). Acton, ACT: ANU Press and Aboriginal History Inc. ISBN 9781760460129.