Jews played an important role in the American civil rights movement, forming alliances with African American leaders and organizations. Jewish individuals and groups like the Anti-Defamation League actively supported the movement against legalized racial injustice. Several prominent Jewish leaders such as Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel and Jack Greenberg marched alongside figures like Martin Luther King Jr. and also contributed significantly to landmark legal victories.[1]

This collaboration extended beyond symbolism to encompass financial support, legal expertise, and grassroots activism, reinforcing the movement's strength. With many Jews taking up leadership positions within the NAACP.[2] The collaboration between Jews and African Americans helped each minority address legalized societal limits.[3]

Background[edit]

Overview of the civil rights movement[edit]

The civil rights movement, spanning from the mid-1950s to the late 1960s, was an organized effort to obtain legalized racial equality and justice in the United States. Rooted in the aftermath of slavery and segregation, the movement sought to highlight, discuss, and dismantle legalized discrimination based on race by studying and applying the words of the Sermon on the Mount, the documents of America's Founding Fathers, and the words and techniques of Mohandas Gandhi.[4][5][6]

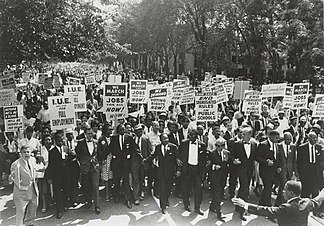

Led by prominent figures like Martin Luther King Jr., Rosa Parks, and James Bevel, activists employed nonviolence, nonviolent civil disobedience, protests, and legal challenges to peacefully address legalized racial inequality. Landmark events, such as the Montgomery bus boycott, the Birmingham children's crusade, the March on Washington, the Selma to Montgomery marches, and the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Voting Rights Act of 1965, and Fair Housing Act of 1968, marked significant milestones in ending legalized segregation and institutionalized racism. The Civil Rights Movement laid the groundwork for subsequent social justice movements, shaping the national dialogue on equality, civil liberties, and the ongoing pursuit of a more just and inclusive society.[6]

Overview of Jews and Jewish organizations in the civil rights movement[edit]

Jewish individuals and organizations played a pivotal role in the civil rights movement, contributing significantly to the fight against racial injustice. Since the outset of the Civil Rights Movement, Black and Jewish communities have stood in solidarity.[7] In 1909, W.E.B. Du Bois, Julius Rosenthal, Lillian Wald, Rabbi Emil G. Hirsch, Stephen Wise, and Henry Malkewitz formed the NAACP. In 1910, other prominent figures established the Urban League. Collaboration continued in 1912 when Julius Rosenwald and Booker T. Washington worked together to improve Southern Black education. These early partnerships exemplify a shared dedication to civil rights, equality, and education, laying the groundwork for a lasting alliance between Black and Jewish communities.[7][8]

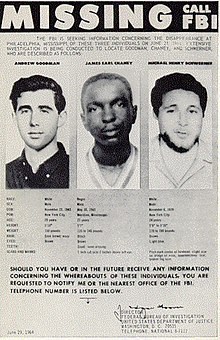

About 50 percent of the civil rights attorneys in the South during the 1960s were Jews, as well as over 50 percent of the Whites who went to Mississippi in 1964 to challenge Jim Crow laws.[3][7] Many Jews, deeply rooted in their historical experiences of persecution, identified with the struggles of African Americans and were motivated by a shared commitment to social justice. Within organizations like the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), Jewish leaders such as Joel Elias Spingarn and his brother Arthur B. Spingarn were instrumental in shaping legal strategies and advocating for equal rights.[9] The Anti-Defamation League (ADL) expanded its mission beyond combating anti-Semitism to address all forms of discrimination.[10] This shift reflected a broader commitment to fighting racial injustice, with the ADL actively supporting African American leaders and causes. The American Jewish Congress, another influential organization, saw leaders like Rabbi Joachim Prinz actively participating in key civil rights events, including the historic March on Washington in 1963. On an individual level, figures like Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel marched alongside Martin Luther King Jr., emphasizing the intersectionality of their struggles. The tragic deaths of Michael Schwerner and Andrew Goodman during the Freedom Summer highlighted the personal risks some Jewish activists faced.[11]

Jews and civil activism in the US[edit]

Jews as a minority in the US[edit]

Major waves of Jewish immigration to the United States commenced in the 19th century, with the first notable wave featuring German-speaking Jews seeking economic opportunities and religious freedoms.[12] However, it was the latter part of the 19th century and the early 20th century that witnessed a significant surge, marked by Eastern European Jews fleeing persecution and economic hardships.[12] These immigrants, primarily Ashkenazi Jews, settled in urban areas, particularly New York City, forming vibrant communities.[13] Jews' affiliation with other minorities in the U.S. can be traced to shared experiences of marginalization and discrimination. Having faced anti-Semitism, Jews empathized with the struggles of African Americans and other minority groups. This shared understanding of oppression and a commitment to social justice created natural alliances.[14][15][16][17]

Jews in social justice movements prior to the civil rights movement[edit]

Prior to the civil rights movement, Jewish individuals were actively engaged in various social justice causes, showcasing a commitment to fighting injustice and inequality. In the early 20th century, Jewish immigrants, particularly those from Eastern Europe, faced harsh working conditions in industries such as garment manufacturing. This led to Jewish participation in labor movements, advocating for fair wages and improved working conditions. The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire in 1911, which claimed the lives of predominantly Jewish and Italian immigrant garment workers, galvanized the Jewish community's involvement in workers' rights. Jewish labor activists, such as Clara Lemlich and Rose Schneiderman, played prominent roles in organizing labor strikes and pushing for legislative reforms.[18]

Additionally, during the Progressive Era, Jewish reformers like Lillian Wald and Jane Addams were instrumental in establishing settlement houses and social welfare organizations. These initiatives aimed to address the socio-economic challenges faced by immigrants in urban centers. Jews were also actively involved in the women's suffrage movement, with figures like Rose Schneiderman advocating for women's rights and suffrage alongside their broader commitment to social justice causes.[19] These instances underscored the early 20th-century Jewish community's activism in addressing societal injustices and paved the way for their continued involvement in subsequent civil rights movements.[20][16]

Civil rights organizations[edit]

NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People)[edit]

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) was established in 1909 in response to the widespread racial violence and discrimination against African Americans. At its inception, the NAACP aimed to dismantle institutionalized racism and secure civil rights for African Americans through legal means. Jewish individuals played a pivotal role in the formation and early leadership of the NAACP. Joel Elias Spingarn, a prominent Jewish scholar, educator, and civil rights advocate, served as the organization's chairman from 1914 to 1919.[21] His brother, Arthur B. Spingarn, also a key figure in the NAACP,[22] chaired the organization for two decades starting in 1919. The Spingarn brothers' influence extended beyond leadership roles, as they actively contributed to legal initiatives within the NAACP.[23] Joel Spingarn, in particular, used his legal acumen to shape the organization's strategies.[24] His dedication to the cause of equal rights was instrumental in advancing the NAACP's legal efforts, including its focus on anti-lynching legislation and educational equality.[25][26]

Jews within the NAACP were notable in leadership positions, advocacy and activism. Their involvement in legal initiatives, often working alongside African American leaders, helped establish the NAACP as a powerful force in challenging discriminatory laws and practices. Jewish lawyers within the NAACP, such as Charles Houston, often referred to as the "man who killed Jim Crow,"[27] and Jack Greenberg who succeeded Thurgood Marshall as the head of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, played critical roles in landmark cases like Brown v. Board of Education which declared state laws establishing separate public schools for black and white students to be unconstitutional.[28] Herbert Hill was the NAACP labor secretary from 1951 to 1977. He played a significant role in advancing the cause of economic justice and equality for African American workers.[29]

ADL (Anti-Defamation League)[edit]

Established in 1913, the Anti-Defamation League (ADL) originally focused on combatting anti-Semitism, aiming to defend the rights of the Jewish community in the United States.[30] As its mission evolved, the ADL expanded its commitment to fighting all forms of discrimination. Notably, during the Civil Rights Movement, the ADL played a pivotal role in supporting African American leaders and organizations. The organization forged a meaningful partnership with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr, providing both financial and legal support. This collaboration underscored the ADL's shared commitment to justice and civil rights, recognizing that the battle against discrimination transcended religious boundaries. In a landmark contribution to the legal landscape of civil rights, the ADL filed an amicus curiae brief in the historic case of Brown v. Board of Education (1954).[31] This pivotal legal maneuver supported the end of racial segregation in public schools, exemplifying the ADL's dedication to the broader principles of equality and justice.[32] Simultaneously, the ADL actively opposed segregationist organizations like the Ku Klux Klan, using its resources to monitor and expose hate groups that promoted discrimination and violence against African Americans.[33][34][35]

Beyond legal advocacy, the ADL initiated educational initiatives aimed at promoting tolerance and combating racism at its roots. These programs sought to address prejudice and discrimination comprehensively, fostering understanding and cooperation among diverse communities. The multifaceted involvement of the ADL in the Civil rights movement, including partnerships, legal interventions, opposition to hate groups, and educational initiatives, showcased the organization's commitment to dismantling systemic discrimination and promoting a society founded on principles of equality and justice.[36][37][34]

American Jewish Congress[edit]

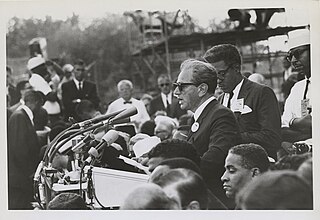

The American Jewish Congress (AJC), founded in 1918, played a significant role in civil rights advocacy during a critical period in American history. Committed to promoting social justice and equality, the AJC actively engaged in various civil rights initiatives.[38] Stanley Levinson, king's advisor also served in the Manhattan board of the AJC.[39] One of the prominent leaders within the organization was Rabbi Joachim Prinz, whose contributions left a lasting impact on the intersection of Jewish and civil rights activism. Rabbi Joachim Prinz, serving as the president of the AJC from 1958 to 1966, emerged as a key figure in the civil rights movement. His leadership emphasized the shared commitment to justice among diverse communities.[40] Rabbi Prinz notably participated in the historic March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in 1963. His impassioned speech during the event, delivered just before Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.'s iconic "I Have a Dream" address, highlighted the interconnected actions against prejudice and discrimination. Rabbi Prinz's eloquent articulation [peacock prose] of the moral imperative for civil rights underscored the AJC's dedication to the broader principles of equality and justice within the context of the larger civil rights movement.[41][38]

Prominent Jewish activists[edit]

Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel[edit]

Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel, born in 1907 in Poland, was a prominent Jewish theologian and philosopher who became a leading figure in the American Civil Rights Movement. Fleeing the Nazis, Heschel immigrated to the United States in 1940, where he contributed profoundly to Jewish scholarship. His philosophy emphasized the spiritual and ethical dimensions of Judaism, advocating for social justice and interfaith understanding. In the 1960s, Rabbi Heschel played a pivotal role in the Civil rights movement, marching alongside Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in key events such as the Selma to Montgomery march.[42] Their collaboration extended beyond symbolism; they shared a deep friendship and mutual respect. Heschel's unique blend of intellectual rigor and spiritual insight added a moral dimension to the Civil Rights Movement, emphasizing the moral duty to confront injustice. His iconic statement, "I felt my legs were praying" during the marches, encapsulates the profound spiritual commitment he brought to the struggle for equality.[43][44]

Michael Schwerner and Andrew Goodman, murder in Mississippi[edit]

Michael Schwerner and Andrew Goodman, along with James Chaney, were civil rights activists murdered during the Freedom Summer campaign in Mississippi in 1964. The three young men were involved in efforts to register African American voters in the deeply segregated South. On June 21, 1964, the trio were investigating the burning of a black church when they were arrested by local law enforcement. Later that evening, they were released but were ambushed by members of the Ku Klux Klan.[45] The activists were brutally beaten and murdered, their bodies buried in an earthen dam.[45] The deaths of Schwerner, Goodman, and Chaney shocked the nation and intensified the urgency of the Civil Rights Movement.[46] Outrage over the murders contributed to increased national attention on the struggles in the South. The incident became a catalyst for the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, both landmark pieces of legislation aimed at dismantling segregation and ensuring the right to vote for African Americans.[47] In 1967, seven men, including Klan leader Edgar Ray Killen, were convicted. Despite the convictions, it took decades for all those responsible to face justice.[45]

Jack Greenberg[edit]

Jack Greenberg (1924–2016) was a distinguished American attorney and civil rights champion known for his leadership at the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund (LDF) from 1961 to 1984. Succeeding Thurgood Marshall,[48][28] Greenberg played a crucial role in advancing the legal fight against racial segregation and discrimination during the tumultuous era of the Civil Rights Movement. His tenure marked a continuation of the LDF's commitment to strategic litigation for social change. Greenberg's legal contributions were pivotal in several landmark cases, including the successful defense of James Meredith's right to attend the University of Mississippi in 1962.[48][28] He also played a key role in the groundbreaking case Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Education (1969), which compelled the immediate desegregation of public schools. Greenberg's legal acumen and strategic vision demonstrated the transformative impact of targeted litigation in dismantling institutionalized racism. Greenberg left an enduring legacy in civil rights history. His leadership at the LDF solidified the organization's role as a force in the ongoing movement for racial justice in the United States.[48][28][49]

Joachim Prinz[edit]

Rabbi Joachim Prinz, drawing from his experiences in Germany during Hitler's regime, empathized with the African-American struggle in the United States. During an exploratory visit in 1937 and upon his return to Germany, Prinz expressed his solidarity with African-Americans, emphasizing parallels between their plight and that of German Jews. Settling in Newark, a city with a significant minority community, Prinz spoke against discrimination from his pulpit and actively participated in protests across the U.S., advocating against racial prejudice in various aspects of life.[50][51] At the 1960 AJC Convention he said the following:

(As Jews), we work for freedom and equality. This is the heart of what we call the civil rights program....These are not mere words. These are the ideas which...have come to mean so much from the days when the author of third book of Moses coined that great sentence about liberty which is engraved upon the Liberty Bell in Philadelphia.[52]

As president of the American Jewish Congress (AJC), Prinz sought to position the organization prominently in the civil rights movement. He met with Martin Luther King Jr. in 1958, requesting support for a conference on integration at the White House. Prinz, a key speaker at the March on Washington in 1963, stressed the importance of speaking out against discrimination based on his experiences in Nazi Germany. His address preceded Martin Luther King Jr.'s famous "I Have a Dream" speech. There he said: "the most urgent, the most disgraceful, the most shameful and the most tragic problem is silence." Prinz continued his involvement in civil rights, attending King's funeral in 1968 after his assassination.[52][51]

Collaboration, challenges and legacy[edit]

The Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s witnessed a significant and transformative collaboration between African American and Jewish leaders, marking a critical alliance against racial segregation and discrimination in the United States.[53] This partnership emerged from a shared commitment to justice, equality, and the dismantling of institutionalized racism. African Americans and Jews, both historically marginalized groups, found common ground in their struggles for civil rights and civil liberties. A key factor in this collaboration was the recognition of the historical parallels between the Jewish experience and the African American struggle.[53][54][55]

Both communities had faced discrimination, prejudice, and violence, fostering a mutual understanding of the challenges each group confronted. Jewish leaders and organizations, such as the Anti-Defamation League and the American Jewish Congress, played instrumental roles in supporting the Civil rights movement financially, legally, and morally. Prominent Jewish individuals, including rabbis like Abraham Joshua Heschel and legal scholars like Jack Greenberg, actively participated in marches and protests alongside African American leaders. The iconic image of Rabbi Heschel walking arm in arm with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. during the Selma to Montgomery march remains a powerful symbol of this collaboration.[56] However, challenges and tensions were not absent from this collaboration. As the Civil Rights Movement progressed, differences in approach, priorities, and perspectives arose between African American and Jewish leaders. Some tensions were rooted in varying historical and cultural contexts, as well as differences in socio-economic status. Additionally, as the 1960s unfolded, political and ideological shifts contributed to strains in the relationship.[55][57]

The emergence of the Black power movement, pro-Palestinian solidarity and the rise of anti-Zionist sentiment in some segments of the African American community added complexity to the collaboration.[55] As Black people continued to face widespread discrimination and struggled to make progress in society, Black activism became increasingly outspoken about issues such as affirmative action[58] that Jews often opposed because of their similarity to quotas.[59] Many liberal Jews also began to move out of areas with increasing Black populations, due to what Cheryl Greenberg describes as the perceived "deterioration of their schools and neighborhoods", sometimes also citing fears of violence due to civil rights protests as a motivator.[60] While many Jewish people continued to support civil rights, the dynamic shifted, and some Jewish leaders faced criticism from within their own communities for their perceived alignment with movements increasingly critical of Israel.[61]

Despite these challenges, the collaboration between African American and Jewish leaders during the Civil rights movement left an enduring legacy (e.g., Jews demonstrated overwhelming condemnation of the 2020 George Floyd killing).[62] The achievements of this partnership include legislative victories like the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which dismantled legal barriers to equality.[63][64][65]

Representative John Lewis, a civil rights icon, played a pivotal role in fostering collaboration between Black and Jewish communities. In 1982, he joined forces with concerned citizens from Atlanta's Black and Jewish communities to campaign for the renewal of the Voting Rights Act, renewing the bond between these communities.[8] Lewis marched alongside Jewish community members and co-established the Atlanta Black-Jewish Coalition, emphasizing open dialogue and partnership. Throughout his career, Lewis consistently spoke out against antisemitism, advocated for Israel, and supported the Soviet Jewry movement in the 1970s and 1980s.[8] His longstanding relationship with AJC included receiving various honors, and he served as a founding co-chair for the Congressional Caucus on Black-Jewish Relations.[8]

See also[edit]

Civil rights movement portal

Civil rights movement portal Judaism portal

Judaism portal- Joseph Gelders (1898–1950), Jewish civil rights activist

References[edit]

- ^ Forman, Seth (1997). "The Unbearable Whiteness of Being Jewish: Desegregation in the South and the Crisis of Jewish Liberalism". American Jewish History. 85 (2): 121–142. ISSN 0164-0178. JSTOR 23885481. Archived from the original on 2023-11-27. Retrieved 2023-11-27.

- ^ "A Brief History of Jews and the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s | Religious Action Center of Reform Judaism". rac.org. Archived from the original on 2023-12-03. Retrieved 2023-11-27.

- ^ a b "'Then and Now: Black-Jewish Relations in the Civil Rights Movement'". Penn Today. 2020-11-19. Archived from the original on 2023-11-27. Retrieved 2023-11-27.

- ^ "Gandhi's Influence on the Civil Rights Movement in the United States – FOR-USA". 29 September 2020. Archived from the original on 2023-09-24. Retrieved 2023-11-30.

- ^ Cambridge, The Founding Fathers and civil rights, Ron Fieldhttps://assets.cambridge.org/97805210/00505/excerpt/9780521000505_excerpt.pdf

- ^ a b "Civil Rights Movement: Timeline, Key Events & Leaders". HISTORY. 2023-10-12. Archived from the original on 2020-04-11. Retrieved 2023-11-27.

- ^ a b c "PBS – From Swastika to Jim Crow – Black-Jewish Relations". PBS. 2002-10-02. Archived from the original on 2002-10-02. Retrieved 2023-11-27.

- ^ a b c d "10 Great Moments of #BlackJewishUnity | AJC". www.ajc.org. 2020-09-10. Archived from the original on 2023-11-27. Retrieved 2023-11-27.

- ^ "Opinion | What We Can Learn From The Jews of the NAACP About Intersectional Organizing". The Forward. 2019-09-12. Archived from the original on 2023-11-27. Retrieved 2023-11-27.

- ^ "Anti-Defamation League | Fighting Hate & Discrimination | Britannica". www.britannica.com. 2023-11-18. Archived from the original on 2023-11-20. Retrieved 2023-11-27.

- ^ "Murdered Jewish Civil Rights Workers to Receive Presidential Medal". Haaretz. Archived from the original on 2023-04-10. Retrieved 2023-11-30.

- ^ a b Berlin, Irving; Arendt, Hannah; Einstein, Albert; Lazarus, Emma; Potter, Albert; Smulewitz, Solomon; Rosenberg, Leo; Rubinstein, M.; Chambers, Charles (2004-09-09). "A Century of Immigration, 1820-1924 - From Haven to Home: 350 Years of Jewish Life in America | Exhibitions (Library of Congress)". www.loc.gov. Archived from the original on 2023-11-27. Retrieved 2023-12-07.

- ^ Staff, Unpacked (2022-04-01). "The history of Jewish life in America". Unpacked. Archived from the original on 2023-11-27. Retrieved 2023-11-27.

- ^ https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1271&context=ghj Archived 2023-05-08 at the Wayback Machine May 2021 The Complex Relationship between Jews and African Americans in the Context of the Civil Rights Movement Hannah Labovitz Gettysburg College

- ^ Higham, John (1957). "Social Discrimination Against Jews in America, 1830–1930". Publications of the American Jewish Historical Society. 47 (1): 1–33. ISSN 0146-5511. JSTOR 43059004. Archived from the original on 2023-12-11. Retrieved 2023-11-27.

- ^ a b "The Jewish Americans . Political Activism | PBS". www.pbs.org. Archived from the original on 2023-06-10. Retrieved 2023-11-27.

- ^ "Jews in the Civil Rights Movement". My Jewish Learning. Archived from the original on 2015-04-02. Retrieved 2023-11-27.

- ^ Terrell, Ellen. "Research Guides: This Month in Business History: Founding of The International Ladies' Garment Workers' Union (ILGWU)". guides.loc.gov. Archived from the original on 2023-11-27. Retrieved 2023-11-27.

- ^ "Feminism in the United States". Jewish Women's Archive. 23 June 2021. Archived from the original on 2023-11-27. Retrieved 2023-11-27.

- ^ American Jews and Their Social Justice Involvement: Evidence from a National Survey Steven M. Cohen* and Leonard Fein *The Hebrew University and the Florence G. Heller/JCCA Research Center https://www.bjpa.org/content/upload/bjpa/c__w/Amos%20Social%20Justice%20Report.pdf Archived 2023-06-19 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Joel Elias Spingarn | American writer, literary critic, educator, and civil rights activist | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Archived from the original on 2023-11-27. Retrieved 2023-11-27.

- ^ https://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt4h4nc3tz/ Archived 2023-05-29 at the Wayback Machine [Identification of item], Arthur B. Spingarn Papers (Collection 1476). UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles.

- ^ Fowle, Farnsworth (1971-12-02). "Arthur Spingarn of N.A.A.C.P. Is Dead". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 2023-11-27. Retrieved 2023-11-27.

- ^ www.bibliopolis.com. "J.E. Spingarn and the Rise of the NAACP, 1911–1939 by B. Joyce Ross on Ian Brabner, Rare Americana, LLC". Ian Brabner, Rare Americana, LLC. Archived from the original on 2023-11-27. Retrieved 2023-11-27.[page range too broad]

- ^ https://northerncity.library.temple.edu/exhibits/show/civil-rights-in-a-northern-cit/people-and-places/jewish-african-american-relati Archived 2023-11-27 at the Wayback Machine JEWISH-AFRICAN AMERICAN RELATIONS By Amira Rose Schroeder

- ^ Back in Time to 1909: The Black Jewish Relationship and the founding of the NAACP, archived from the original on 2023-11-27, retrieved 2023-11-27

- ^ "The Man Who Killed Jim Crow" Archived October 20, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. America.gov. Retrieved October 14, 2009.

- ^ a b c d "Jack Greenberg". www.law.columbia.edu. Archived from the original on 2023-11-27. Retrieved 2023-11-27.

- ^ Greenhouse, Steven (2004-08-21). "Herbert Hill, a Voice Against Discrimination, Dies at 80". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 2023-12-11. Retrieved 2023-11-27.

- ^ "Protect Civil Rights | ADL". www.adl.org. Archived from the original on 2023-11-27. Retrieved 2023-11-27.

- ^ "Brown v. Board of Education | ADL". www.adl.org. Archived from the original on 2023-11-27. Retrieved 2023-11-27.

- ^ "Find Local & Regional Offices of National & Overseas Agencies". Greater Miami Jewish Federation. Archived from the original on 2023-11-27. Retrieved 2023-11-27.

- ^ Baig, Edward C. "Redirecting hate: ADL hopes Googling for KKK or jihad will take you down a different path". USA TODAY. Archived from the original on 2020-11-07. Retrieved 2023-11-27.

- ^ a b SALES, BEN (20 April 2018). "How a Jewish civil rights group became a villain on the far-left". Times of Israel. Archived from the original on 16 June 2019. Retrieved 27 November 2023.

- ^ "Plan to Fight Ku Klux Klan Outlined by Anti-defamation League". Jewish Telegraphic Agency. 2015-03-20. Archived from the original on 2023-11-27. Retrieved 2023-11-27.

- ^ "March on Washington | ADL". www.adl.org. 2017-01-13. Archived from the original on 2023-11-27. Retrieved 2023-11-27.

- ^ "Our History | ADL". www.adl.org. Archived from the original on 2023-12-06. Retrieved 2023-11-27.

- ^ a b "American Jewish Congress (AJC) | The Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute". kinginstitute.stanford.edu. Archived from the original on 2023-11-27. Retrieved 2023-11-27.

- ^ "Levison, Stanley David | The Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute". kinginstitute.stanford.edu. Archived from the original on 2023-11-27. Retrieved 2023-11-27.

- ^ "Joachim Prinz (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Archived from the original on 2020-11-17. Retrieved 2023-11-27.

- ^ Feldstein, Zavi (2021-03-08). "The Problem of Silence: Rabbi Joachim Prinz Speech at the March on Washington". American Jewish Archives. Archived from the original on 2023-11-27. Retrieved 2023-11-27.

- ^ "MLK and Rabbi Heschel Fought for Civil Rights Together. Their Daughters Say the Struggle Isn't Done". Haaretz. Archived from the original on 2023-02-01. Retrieved 2023-11-27.

- ^ "Heschel, Abraham Joshua | The Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute". kinginstitute.stanford.edu. Archived from the original on 2023-11-27. Retrieved 2023-11-27.

- ^ "Two Friends, Two Prophets". Plough. Archived from the original on 2023-07-11. Retrieved 2023-11-27.

- ^ a b c "Murder in Mississippi | American Experience | PBS". www.pbs.org. Archived from the original on 2023-11-30. Retrieved 2023-11-27.

- ^ "Murder in Mississippi". www.nrm.org. Archived from the original on 2023-11-27. Retrieved 2023-11-27.

- ^ Foner, Eric; Garraty, John A. (John Arthur); Society of American Historians (1991). The Reader's companion to American history. Internet Archive. Boston : Houghton-Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-51372-9.[page range too broad]

- ^ a b c Legal Defense Fund, LDF DIRECTOR-COUNSELS Jack Greenberg1961-1984 https://www.naacpldf.org/about-us/history/jack-greenberg/ Archived 2023-11-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Severo, Richard; McDonald, William (2016-10-13). "Jack Greenberg, a Courthouse Pillar of the Civil Rights Movement, Dies at 91". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 2019-06-28. Retrieved 2023-11-27.

- ^ Prinz, Joachim (4 February 2015). "Letter from Joachim Prinz to Martin Luther King, Jr". The Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute. Stanford University. Archived from the original on 20 March 2023. Retrieved 20 March 2023.

- ^ a b Fowler, Glenn (1988-10-01). "Joachim Prinz, Leader in Protests For Civil-Rights Causes, Dies at 86". The New York Times. p. 33. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 2020-02-22. Retrieved 2020-11-12.

- ^ a b Pasternak, Rachel Nierenberg; Fisher, Rachel Eskin; Price, Clement (2014-11-06). "Rabbi Joachim Prinz: The Jewish Civil Rights Leader". Moment Magazine. Archived from the original on 2021-02-06. Retrieved 2020-11-12.

- ^ a b "The RAC and the Civil Rights Movement | Religious Action Center of Reform Judaism". rac.org. Archived from the original on 2023-11-27. Retrieved 2023-11-27.

- ^ Mohl, Raymond A. (1999). ""South of the South?" Jews, Blacks, and the Civil Rights Movement in Miami, 1945–1960". Journal of American Ethnic History. 18 (2): 3–36. ISSN 0278-5927. JSTOR 27502414. Archived from the original on 2023-12-11. Retrieved 2023-11-27.

- ^ a b c "Tensions in Black-Jewish Relations". Jewish Women's Archive. Archived from the original on 2023-11-27. Retrieved 2023-11-27.

- ^ Becker, Mort. "We must remember Abraham Joshua Heschel, Martin Luther King Jr.'s great prophet | Opinion". The Journal News. Archived from the original on 2023-11-27. Retrieved 2023-11-27.

- ^ "The Civil Rights Movement: Major Events and Legacies | AP US History Study Guide from The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History". www.gilderlehrman.org. 2012-07-31. Retrieved 2023-11-27.

- ^ Ajunwa, Ifeoma (2021-09-01). "WHAT TO THE BLACK AMERICAN IS THE MERITOCRACY? Comment on M. Sandel's The Tyranny of Merit". American Journal of Law and Equality. 1: 39–45. doi:10.1162/ajle_a_00002. ISSN 2694-5711.

- ^ Schnur, Dan (2023-07-06). "Jews and Affirmative Action". Jewish Journal. Retrieved 2024-02-28.

- ^ Greenberg, Cheryl Lynn (2006). Troubling the waters: Black-Jewish relations in the American century. Politics and society in twentieth-century America. Princeton (N.J.): Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-05865-8.

- ^ "The Alignment of BDS and Black Lives Matter: Implications for Israel and Diaspora Jewry". Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs. Archived from the original on 2023-11-27. Retrieved 2023-11-27.

- ^ Congress, World Jewish. "World Jewish Congress". World Jewish Congress. Archived from the original on 2023-11-27. Retrieved 2023-11-27.

- ^ "The Past and Future of Black–Jewish Relations | SAPIR Journal". sapirjournal.org. Archived from the original on 2023-11-27. Retrieved 2023-11-27.

- ^ Coates, Russell (2023-06-08). "A history of free speech in America | Learn Liberty". Archived from the original on 2023-11-27. Retrieved 2023-11-27.

- ^ Carroll, Nicole. "The Backstory: Civil rights lessons. Why we need to learn about 1961 to better understand 2021". USA TODAY. Archived from the original on 2023-11-27. Retrieved 2023-11-27.