Lizard was built to the same design as HMS Carysfort (pictured)

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | HMS Lizard |

| Ordered | 13 April 1756 |

| Builder | Henry Bird, Globe Stairs, Rotherhithe |

| Laid down | 5 May 1756 |

| Launched | 7 April 1757 |

| Completed | 1 June 1757 at Deptford Dockyard |

| Commissioned | March 1757 |

| Honours and awards |

|

| Fate |

|

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | 28-gun Coventry-class sixth-rate frigate |

| Tons burthen | 59487⁄94 (bm) |

| Length |

|

| Beam | 33 ft 11 in (10.3 m) |

| Depth of hold | 10 ft 6 in (3.20 m) |

| Sail plan | Full-rigged ship |

| Complement | 200 |

| Armament |

|

HMS Lizard was a 28-gun Coventry-class sixth-rate frigate of the Royal Navy, in service from 1757 to 1828. Named after the Lizard, a peninsula in southern Cornwall, she was a broad-beamed and sturdy vessel designed for lengthy periods at sea. Her crewing complement was 200 and, when fully equipped, she was armed with 24 nine-pounder cannons, supported by four three-pounders and twelve 1⁄2-pounder swivel guns. Despite her sturdy build, she was plagued with maintenance problems and had to be repeatedly removed from service for repair.

Lizard saw active service between 1757 and 1793, during British involvement in the Seven Years' War, the American Revolutionary War and the French Revolutionary War. She assisted in major naval operations in the Caribbean and North America, including the British capture of Quebec City and Montreal, the Siege of Havana and the Battle of St Kitts. She also secured a total of nine victories at sea over enemy vessels, principally French privateers in action in American and European waters.

Removed from active service in 1794, Lizard was eventually refitted as a hospital ship and assigned to a berth near Burntwick Island where she received merchant seamen suspected of suffering from diseases including yellow fever and bubonic plague. What had been intended as a temporary assignment continued for 28 years, with Lizard eventually becoming the last of the Coventry-class vessels still in operation. She was removed from service, 71 years after her launch, and was sold for scrap at Deptford Dockyard in September 1828.

Construction[edit]

Design and crew[edit]

Lizard was an oak-built 28-gun sixth rate, one of 18 vessels forming part of the Coventry class of frigates. As with others in her class she was loosely modeled on the design and external dimensions of HMS Tartar, launched in 1756 and responsible for capturing five French privateers in her first twelve months at sea.[1] The Admiralty Order to build the Coventry-class vessels was made after the outbreak of the Seven Years' War, and at a time in which the Royal Dockyards were fully engaged in constructing or fitting-out the Navy's ships of the line. Consequently, despite Navy Board misgivings about reliability and cost, contracts for all but one of Coventry-class vessels were issued to private shipyards with an emphasis on rapid completion of the task.[2]

Contracts for Lizard's construction were issued on 13 April 1756 to shipwright Henry Bird of Globe Stairs, Rotherhithe. It was stipulated that work should be completed within twelve months for a 28-gun vessel measuring approximately 590 tons burthen. Subject to satisfactory completion, Bird would receive a fee of £9.9s per ton to be paid through periodic imprests drawn against the Navy Board.[3][4][a] Private shipyards were not subject to rigorous naval oversight, and the Admiralty therefore granted authority for "such alterations withinboard as shall be judged necessary" in order to cater for the preferences or ability of individual shipwrights, and for experimentation with internal design.[1][2]

Lizard's keel was laid down on 5 May 1756, and work proceeded swiftly with the fully built vessel ready for launch by April 1757, well within the stipulated time. In final construction the vessel's hull was slightly larger than contracted, at 594 87⁄94 tons, being 118 ft 8 in (36.2 m) long with a 97 ft 3 in (29.6 m) keel, a beam of 33 ft 11 in (10.34 m), and a hold depth of 10 ft 6 in (3.2 m). These minor variations in dimensions did not affect final settlement of the contract, with Bird receiving the full amount of £5,540.14s for his shipyard's work.[1]

The vessel was named after the Lizard, a peninsula in southern Cornwall that was a maritime landmark for vessels passing along the English Channel. In selecting her name the Board of Admiralty continued a tradition dating to 1644 of using geographic features for ship names; overall, ten of the nineteen Coventry-class vessels were named after well-known regions, rivers or towns.[5][6] With few exceptions the remainder of the class were named after figures from classical antiquity, following a more modern trend initiated in 1748 by John Montagu, 4th Earl of Sandwich in his capacity as First Lord of the Admiralty.[5][6][b]

Lizard's designated complement was 200, comprising two commissioned officers – a captain and a lieutenant – overseeing 40 warrant and petty officers, 91 naval ratings, 38 Marines and 29 servants and other ranks.[8][c] Among these other ranks were four positions reserved for widow's men – fictitious crew members whose pay was intended to be reallocated to the families of sailors who died at sea.[8] Armament comprised 24 nine-pounder cannons located along her gun deck, supported by four three-pounder cannons on the quarterdeck and twelve 1⁄2-pounder swivel guns ranged along her sides.[1]

Sailing qualities[edit]

In sailing qualities Lizard was broadly comparable with French frigates of equivalent size, but with a shorter and sturdier hull and greater weight in her broadside guns. She was also comparatively broad-beamed with ample space for provisions and the ship's mess, and incorporating a large magazine for powder and round shot.[d] Taken together, these characteristics aimed to enable Lizard to tack and wear more reliably than her French equivalents,[10] and to remain at sea for longer periods without resupply.[9][11] She was built with broad and heavy masts which balanced the weight of her hull, improved stability in rough weather and allowed her to carry a greater quantity of sail. The disadvantages of this heavy design were an overall decline in manoeuvrability and slower speed when sailing in light winds.[12]

The frigate was plagued with construction and maintenance difficulties throughout her seagoing career, requiring seven major repairs or refits between 1769 and 1793.[1][e] Private shipyards such as Henry Bird's used thinner hull planking than did the Royal Dockyards, producing less robust vessels which further decreased in seaworthiness after every major repair.[13] Privately built vessels during the Seven Years' War were also hampered by the unavailability of seasoned oak, as the Royal Navy's supply was preferentially allocated to ships of the line. Smaller vessels such as Lizard were therefore routinely repaired with unseasoned timber which could warp as it dried, causing cracks in decks and gun ports and leaks along the hull.[14][15]

Seven Years' War[edit]

North Atlantic, 1757–1758[edit]

Lizard was commissioned by Captain Vincent Pearce in March 1757, while still under construction at Rotherhithe. She was launched on 7 April and sailed to Deptford Dockyard for fitting-out and to take on armament and crew. This was completed by 1 June and Lizard immediately put to sea to join a small squadron under the command of Admiral Samuel Cornish off the southwest coast of Cornwall.[1] Britain had been at war with the French for more than a year, and Royal Navy vessels in waters surrounding England were routinely deployed to escort merchant fleets and hunt French privateers.[16] It was in this second capacity that Lizard secured her first victories at sea, with the capture on 12 July 1757 of a 6-gun French privateer L'Hiver, and the recapture of a British merchantman loaded with rum and sugar which the French vessel had in tow. With assistance from members of Lizard's crew, both captured craft were sent in to the Irish port of Kinsale as prizes.[17]

The frigate was reassigned in 1758 to a squadron under the command of Admiral George Anson, which was blockading the French seaport of Brest.[1][18] Anson had directed that the 74-gun ship of the line HMS Shrewsbury maintain a position close to the Brest shoreline in order to observe the French fleet. Lizard was sent in support, accompanied by the 20-gun sixth-rate HMS Unicorn. On 12 September the three Royal Navy vessels were in position when their crews observed an approaching convoy of French coasters, escorted by the frigates Calypso and Thetis. The Convoy sought to reach Brest without engaging Shrewsbury, by sailing very close to land to take advantage of their shallow draft. Both Lizard and Unicorn moved toward the French, with Lizard successfully interposing herself between the coasters and their escorting frigates. The French frigate Calypso attempted to manoeuvre around Lizard and return to the convoy, but ran aground and was wrecked on the shore. The coasters scattered, with many forced seaward where they were captured or destroyed by the British. Lizard and Unicorn then returned to their station alongside Shrewsbury. While at this post on 2 October, Lizard also pursued and defeated Duc d'Hanovre', a 14-gun French privateer.[1][18]

The Americas, 1759–1763[edit]

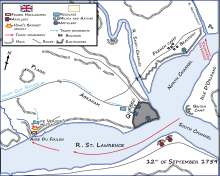

Captain Doake took command in mid-October, bringing Admiralty orders reassigning Lizard to North American waters as part of a fleet supporting a planned invasion of Québec in 1759. The winter idled by as the invasion force was assembled, and it was not until 17 February 1759 that Lizard finally departed Spithead for Halifax, Nova Scotia, in company with other Royal Navy vessels. On arrival in Nova Scotia, she joined the combined British fleet of 52 naval vessels and 140 transports, under the overall command of Vice-Admiral Charles Saunders. On 23 June the fleet passed L'Isle-aux-Coudres on the St Lawrence River, and three days later had anchored before the French stronghold of Quebec City. There were few French vessels at Quebec City, and little useful work for frigates such as Lizard, though her sister vessel Trent was able to bombard and destroy an artillery battery on the shoreline.[19] Lizard remained beneath Quebec throughout July and August, while other parts of Saunders' fleet reconnoitred and captured the river above the town. On 12 September Lizard's marines were part of a landing below the town as a feint to distract from the real British landing by forces under General James Wolfe, on the Plains of Abraham upstream.[20] Wolfe's assault was successful, and Quebec City was surrendered on 17 September. Lizard then returned to England with the majority of the fleet.[1][20]

The British campaign in Québec continued in early 1760 with plans for an assault on Montreal. After wintering at Portsmouth, Lizard was back in North American waters by February as reinforcement for a British squadron on the St Lawrence River.[1][21] After the fall of Montreal in September she was reassigned to Britain's Leeward Islands Station as a privateer hunter and as protection for merchant convoys.[22] The British had set their sights on the French Caribbean stronghold of Martinique, with Secretary of State for the Southern Department, Sir William Pitt, directing that all available resources be committed to its invasion. An army of 13,000 troops was assembled, supported by a fleet under Admiral George Rodney.[23] Lizard's armament was increased to 32 guns, and she was added to Rodney's sizeable command which sailed as part of the expedition in January 1762.[1][24] She was present when the British landings commenced but is not recorded as having engaged with enemy forces either there or in the subsequent French defeat at Fort Royal between 25 January and 3 February.[1] Despite this her crew were among those entitled to a formal share of plunder from the French settlement, when this was distributed by Admiralty in 1764.[25]

Lizard returned to the Leeward Islands, where she was made ready to accompany an expected British assault on Havana, Spain's Caribbean capital. In May 1762 a British fleet of around 200 vessels was assembled under Admiral George Pocock to begin the siege. Lizard joined Pocock's fleet in June, and was designated as the flagship of Commodore James Douglas. At around this time James Doake, resigned Lizard's command and was replaced aboard by Captain Francis Banks.[26] Havana fell to the British at the end of July, and by August Lizard had been released to her former duties.[1] War with France and Spain concluded with the signing of the Treaty of Paris in March 1763. Lizard was declared surplus to Navy requirements, and returned to Portsmouth Dockyard in June to be paid off.[1]

Peacetime service[edit]

The frigate was left at anchor for the next six years. A naval survey in 1769 found her unseaworthy and in need of extensive repair. Reconstruction and refitting took 16 months to complete and cost £8,211.16, which was significantly more than the vessel's original construction expense.[1]

On 10 June 1770, a Spanish expedition expelled the British colony at Port Egmont in the Falkland Islands, giving Spain control of the entire British colony. Admiralty ordered a mobilisation of available Navy vessels to escort a British relief expedition to the Falklands. Lizard was one vessel available for this purpose, and she was recommissioned in October 1770 under Captain Charles Inglis, with orders to proceed at once to the British fleet. However, her repairs continued for another two months and it was not until December 1770 that the frigate was considered seaworthy.[1] She was still fitting out at Portsmouth in January 1771 when a treaty between Britain and Spain brought the Falklands dispute to a close.[27]

No longer required for Falklands duty, Lizard made an uneventful return voyage to Gibraltar in June 1771, and then remained at Portsmouth until September when she was assigned to patrol and privateer-hunting along the North American coastline.[28][1] After three years at this station she returned to England to be paid off and her crew dispersed.[1]

American Revolutionary War[edit]

Lizard was refitted for active service in June 1775, following the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War. Recommissioned under Captain John Hamilton, she was again assigned to service along the St Lawrence River, on the same station that she had occupied in the previous war in 1759. Command was passed to Captain Thomas Mackenzie in June 1776. Six months later, on 4 December she encountered and captured the American privateer Putnam. She sailed for England in early 1777 and was refitted and repaired at Plymouth Dockyard before returning to North American waters for the final time.

On 13 January 1778, Lizard captured the brig Ann off Stono Inlet, North Carolina.[29] On 21 January Lizard, along with HMS Perseus and Carysfort, captured the French ship Bourbon off Edisto Island, South Carolina.[30] On 27 January she and HMS Carysfort captured French brig 'Flambeau" 19 miles off Charles Town, South Carolina.[31] On 28 January she and HMS Carysfort captured French sloop 'Notre Dame des Charmes" 19 miles off Charles Town, South Carolina.[32] On 1 February, 1778 she and HMS Carysfort captured Dutch brig 'Batavear" off the mouth of the Santee River, South Carolina.[33] On 24 February, 1778 she captured French ship "Glanure" 5-6 Leagues off Charles Town.[34] Further refits were conducted at Chatham Dockyard from February to May 1779 and from February to April 1780. These included the copper sheathing of her hull to protect the timbers from shipworm. Mackenzie was replaced in command by Captain Francis Parry, and Lizard was thereafter assigned to service in the English Channel where, on 18 May 1780, she captured the enemy cutter Jackal.[1]

In 1781 Captain Parry was promoted to command of the 44-gun Actaeon, and was replaced aboard Lizard by Captain Edmund Dod. The frigate was assigned to protect a convoy of merchant vessels sailing for the West Indies, departing from England in March.[35] On arrival in April, Lizard was formally added to the Navy's Leeward Islands Station and took up her post in the waters off Martinique and Jamaica. In January 1782 she was assigned to a fleet under Admiral Sir Samuel Hood, which had sailed to the relief of the besieged British settlement on Saint Kitts. While en route to Saint Kitts at the head of Hood's fleet, Lizard encountered and captured the 16-gun French cutter l'Espion, laden with a cargo of artillery shells and other ammunition. The French vessel was taken as a prize.[36]

Lizard returned to the Leeward Islands following the relief of St. Kitts. However, peace negotiations with France from 1782 were accompanied by a decline in naval activity, leaving the frigate surplus to Admiralty's needs. In September 1782, she returned to Britain where she was decommissioned and her crew paid off for transfer to other vessels.[1]

French Revolutionary Wars[edit]

Lizard remained at anchor on the River Thames for six years, undergoing desultory repairs to maintain her seaworthiness. Civil unrest in France in early 1790 encouraged Admiralty to increase the number of vessels in active service, and Lizard was among those selected for a return to sea. She was refitted at the privately owned Blackwall Yard from May to August 1790 and recommissioned under Captain John Hutt in early September.[1]

In preparation for war, the frigate spent eight months as a receiving ship for sailors seized by a press gang for compulsory naval service. On returning to Spithead in June 1791 she was joined to a squadron of six ships of the line under the overall command of Admiral Hood, which was sailing for Jamaica with two regiments of the Coldstream Guards.[37][38] The voyage proceeded without incident, and Lizard returned to Britain in September 1791 via the Scottish port of Leith, where her crew were discharged.[1][39] Refitted at Portsmouth Dockyard, she was returned to sea in December 1792 for service during the War of the First Coalition against France. Under Captain Thomas Williams, the frigate was assigned to privateer hunting in the North Sea. In March 1793 she secured three successive victories, capturing the French privateers Les Trois Amis, Las Vaillant Custine and the 8-gun Le Sans-Cullotte, each of which was sent back to British ports as prize vessels. Despite these successes, the forty-year-old vessel was reaching the end of her seagoing career; after one final year in the North Sea she was returned to Portsmouth in May 1794 and permanently removed from active military roles.[1]

Hospital ship[edit]

"...two or three old Men of War that will serve as hulks to be fitted up as Lazarettes ... and one of smaller dimensions [Lizard] to be fitted up as an Hospital for the reception of the sick if any such be found on board, (as well as) ... an able medical person... to examine into the health of the crews and other persons on board ships arriving from the Levant."

– Excerpt from the 1799 Order of the Privy Council establishing Lizard as a hospital ship and authorising employment of a doctor to care for those aboard.[40]

The ageing vessel lay unused at Portsmouth for the next five years. In 1797 she was placed under the nominal command of Lieutenant John Buller, who was relieved by Lieutenant James Macfarland in the following year.[1] Under Macfarland's command in 1799, Lizard was brought to Chatham Dockyard for internal modifications to convert her into a hospital ship.[41] These works coincided with public fears that yellow fever and bubonic plague could be brought to Britain via vessels from the eastern Mediterranean.[40] On completion of the fitout in 1800 Lizard was sailed to Stangate Creek, near Burntwick Island in Kent, to care for sick seafarers discharged from quarantined merchantmen.[40] She was accompanied by two largely derelict Navy vessels – Valiant and Duke – which were refitted as floating lazarettes.[41][42]

The hospital ship assignment was intended to be temporary, pending construction of a permanent quarantine station atop the nearby Chetney Hill. However work on this facility was abandoned in 1810 for cost reasons and because the land surrounding the site was swampy and itself a centre for disease.[43] Valiant was returned to sea in 1803, but Lizard and Duke remained at Stangate Creek for the next 28 years, catering for patients transferred from vessels under quarantine at other ports.[42][1] The decrepit Lizard was removed from Navy service in 1828 and towed to Sheerness Dockyard for decommissioning. On 22 September 1828 she was sold, likely as scrap, for the sum of £810.[1]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Bird's £9.9s fee per ton compared unfavourably with an average £9.0s per ton sought by Thames River shipwrights to build 24-gun Royal Navy vessels over the previous decade,[4] but was exactly equal to the average for all Coventry-class vessels built in private shipyards between 1756 and 1765.[5]

- ^ The exceptions to these naming conventions were Hussar, Active and the final vessel in the class, Hind[5][7]

- ^ The 29 servants and other ranks provided for in the ship's complement consisted of 20 personal servants and clerical staff, four assistant carpenters an assistant sailmaker and four widow's men. Unlike naval ratings, servants and other ranks took no part in the sailing or handling of the ship.[8]

- ^ Lizard's dimensional ratios 3.57:1 in length to breadth, and 3.3:1 in breadth to depth, compare with standard French equivalents of up to 3.8:1 and 3:1 respectively. Royal Navy vessels of equivalent size and design to Lizard were capable of carrying up to 20 tons of powder and shot, compared with a standard French capacity of around 10 tons. They also carried greater stores of rigging, spars, sails and cables, but had fewer ship's boats and less space for the possessions of the crew.[9]

- ^ Major repairs or refits were required in 1769–1770, 1775, 1777, 1779, 1783–1784, 1790 and 1793. These do not include refits for changes of use: in 1780 for English Channel service, and in 1799–1800 for reuse as a hospital ship.[1]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa Winfield 2007, p. 227

- ^ a b Rosier, Barrington (2010). "The Construction Costs of Eighteenth-Century Warships". The Mariner's Mirror. 92 (2): 164. doi:10.1080/00253359.2010.10657134.

- ^ Winfield 2007, pp. 229–230

- ^ a b Baugh 1965, pp. 255–256

- ^ a b c d Winfield 2007, pp. 227–231

- ^ a b Manning, T. Davys (1957). "Ship Names". The Mariner's Mirror. 43 (2). Portsmouth, United Kingdom: Society for Nautical Research: 93–96. doi:10.1080/00253359.1957.10658334.

- ^ Winfield 2007, p. 240

- ^ a b c Rodger 1986, pp.348–351

- ^ a b Gardiner 1992, pp. 115–116

- ^ Gardiner 1992, p.95

- ^ Gardiner 1992, pp. 107–108

- ^ Gardiner 1992, pp. 111–112

- ^ Correspondence, Captain Augustus Keppel to John Russell, 4th Duke of Bedford, August 1745. Cited in Baugh 1965, p. 259

- ^ Albion 2000, pp. 133–134

- ^ Baugh 1965, pp.258–259

- ^ Robson 2016, pp.47–48

- ^ "Ireland". The Oxford Journal. Oxford, United Kingdom: W. Jackson. 6 August 1757. p. 2. Retrieved 10 January 2018 – via The British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ a b Clowes 1898, p. 299

- ^ Clowes 1898, p. 207

- ^ a b Clowes 1898, pp. 205–209

- ^ Clowes 1898, pp. 226–227

- ^ Clowes 1898, p. 233

- ^ Robson 2016, pp. 174–175

- ^ "Extract of a Letter from Guadeloupe, December 7". The Derby Mercury. Derby, United Kingdom: S. Drewry. 5 February 1762. p. 1. Retrieved 7 October 2017 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "No. 10442". The London Gazette. 7 August 1764. p. 2.

- ^ Clowes 1898, pp. 245–246

- ^ Clowes 1899, p. 3

- ^ "Extract of a Letter from Portsmouth, June 17". The Caledonian Mercury. Walter Ruddiman and Company. 22 June 1771. p. 2. Retrieved 27 December 2017.

- ^ "Naval Documents of the American Revolution" (PDF). US Government Printing Office via Imbiblio. Retrieved 18 September 2023.

- ^ "Naval Documents of The American Revolution Volume 11 AMERICAN THEATRE: Jan. 1, 1778–Mar. 31, 1778 EUROPEAN THEATRE: Jan. 1, 1778–Mar. 31, 1778" (PDF). U.S. Government printing office via Imbiblio. Retrieved 26 September 2023.

- ^ "Naval Documents of The American Revolution Volume 11 AMERICAN THEATRE: Jan. 1, 1778–Mar. 31, 1778 EUROPEAN THEATRE: Jan. 1, 1778–Mar. 31, 1778" (PDF). U.S. Government printing office via Imbiblio. Retrieved 24 October 2023.

- ^ "Naval Documents of The American Revolution Volume 11 AMERICAN THEATRE: Jan. 1, 1778–Mar. 31, 1778 EUROPEAN THEATRE: Jan. 1, 1778–Mar. 31, 1778" (PDF). U.S. Government printing office via Imbiblio. Retrieved 24 October 2023.

- ^ "Naval Documents of The American Revolution Volume 11 AMERICAN THEATRE: Jan. 1, 1778–Mar. 31, 1778 EUROPEAN THEATRE: Jan. 1, 1778–Mar. 31, 1778" (PDF). U.S. Government printing office via Imbiblio. Retrieved 28 October 2023.

- ^ "Naval Documents of The American Revolution Volume 11 European THEATRE: Jan. 1, 1778–Mar. 31, 1778 American: Jan. 1, 1778–Mar. 31, 1778" (PDF). U.S. Government printing office via Imbiblio. Retrieved 13 November 2023.

- ^ "Monday's Post". Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette. Bath: B. Cruttwell. 22 March 1781. p. 2. Retrieved 2 January 2018 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "No. 12277". The London Gazette. 9 March 1782. p. 1.

- ^ "Thursday's and Friday's Posts". The British Chronicle. Hereford, United Kingdom: J. Duncumb. 20 October 1790. p. 1. Retrieved 4 January 2018 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Home News: Portsmouth, Gosport and Chichester, Post". The Hampshire Chronicle. Winchester, United Kingdom: J. Wilkes. 13 June 1791. p. 3. Retrieved 4 January 2018 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Edinburgh". The Caledonian Mercury. Edinburgh, United Kingdom: Robert Allan. 29 September 1791. p. 3. Retrieved 4 January 2018 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ a b c Froggatt, P. (1964). "The Lazaret on Chetney Hill". Medical History. 8 (1): 52. doi:10.1017/S0025727300029082. PMC 1033335.

- ^ a b "Canterbury, November 26". Kentish Gazette. Kent, United Kingdom: W. Bristow. 26 November 1799. p. 4. Retrieved 30 January 2018.

- ^ a b Winfield 2007, p. 61

- ^ Froggatt, P. (1964). "The Lazaret on Chetney Hill". Medical History. 8 (1): 55–56. doi:10.1017/S0025727300029082. PMC 1033335.

Bibliography[edit]

- Albion, Robert Greenhalgh (2000). Forests and Sea Power: The Timber Problem of the Royal Navy, 1652–1862. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1557500215.

- Baugh, Daniel A. (1965). British Naval Administration in the Age of Walpole. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691624297.

- Clowes, William Laird (1898). The Royal Navy: A History from the Earliest Times to the Present. Vol. 3. London: Sampson, Low, Marston and Company. OCLC 645627800.

- Clowes, William Laird (1899). The Royal Navy: A History From the Earliest Times to the Present. Vol. 4. London: Sampson Low, Marston and Company. OCLC 940253201.

- Gardiner, Robert (1992). The First Frigates. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0851776019..

- Rodger, N. A. M. (1986). The Wooden World: An Anatomy of the Georgian Navy. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0870219871.

- Winfield, Rif (2007). British Warships of the Age of Sail 1714–1792: Design, Construction, Careers and Fates. Seaforth. ISBN 9781844157006.