Otto III, Holy Roman Emperor, also called miribilia mundi, despite his short life (he died in 1002, at age 22), is a historical figure who attracts considerable scholarly attention as well as inspires numerous artistic and popular depictions.[2]

An intellectual emperor, even deemed a genius (although in older research, it was often pointed out that this genius leaned towards grandiose but unrealistic plans), Otto greatly developed the idea of empire with both novel and conventional conceptions during his reign.[3][4] His diplomatic activities coincided with and facilitated the Christianization and the spread of Latin culture in different parts of Europe.[5][6] His early death though made his reign "the tale of largely unrealized potential".[3][7][8] Controversies over the emperor, particularly his Renovation program, have remained hotly debated until this day. Lindsay Diggelmann notes that, "His brief life (980-1002) remains rather shadowy, even by the standards of medieval biography. Yet it has assumed an enormous importance in the history of German national consciousness, since many scholars have chosen to see Otto and his predecessors in the Saxon line as the founders of a German empire in the post-Carolingian period."[9]

Otto has a reputation of piety and association with contemporary saints and great intellectual figures, as well as romantic legends. The legend (now considered unlikely to be true) of the love between Otto and Stephania, the widow of Otto's relative and enemy Crescentius, as well as Otto's poisoning by her, is a particularly frequent subject of artistic depictions of the emperor.

Historiography[edit]

Otto III and his reign have always been controversial. His nineteenth century critics, notably Wilhelm von Giesebrecht attacked him for failing in his duty towards his (German) nation and chasing after whimsical, unrealistic fantasies.[11][12]

With his work Kaiser, Rom und Renovatio (published for the first time in 1929), Percy Ernst Schramm is widely considered the first scholar who has succeeded in reversing the negative image attached to Otto: "Far from being an ineffective dreamer, Otto III re-emerged as a powerful designer of an empire based on a universalistic ideal." From this new perspective, instead of being manipulated by his former teacher Pope Sylvester II (Gerbert of Aurillac), Otto claimed a closer connection to Saint Peter than to the pope through the title servus apostolorum. Otto's version of the renovatio imperii Romanorum strengthened the emperor as defensor ecclesiae, who would subdue and convert barbarians to Christianity. Schramm's new perception faced an uphill battle at first.[13][14] In 1932, Albert Brackmann, although disagreeing with Schramm, presented Otto as a ruler who fitted squarely within the Carolingian-Ottonian traditions and praised "golden Rome" just to glorify and better safeguard the current Rome, and that his rejection of the Donation of Constantine and its legal claims, was only to check the curia's aspiration to power.[15]

Recently, Knut Görich has challenged Schramm's view. Görich argues that what Otto intended to renovate was not the old Empire, but the Roman church and the Papacy.[16][17]

Michel Parisse, reviewing Görich's work, notes that post-Schramm scholars are too focused on debunking the theories of their predecessors (with new theories quickly becoming considered as facts but having questionable facets of their own):[18][a]

Will we one day forget Schramm, whose tree hides the forest from those who are interested in Otto III? After M. Uhlirz, H. Ludat, H. Thomas, J. Fried, K. Görich, will someone decide to rewrite the history of Otto III, not to question the ideas of the predecessors, but to calmly give an account of a great reign, the government of a brilliant young emperor, a very great moment in the history of the Germanic empire, always sketched in the biographies of the princes, never presented as a whole?

Regarding English sources, in 2003, Gerd Althoff's Otto III was translated into English. The work also tries to steer away from older German nationalistic views of the emperor. Julie A. Hofmann praises the book for including a useful section of the historiography concerning Otto III and successfully showing why previous ideas about the emperor are flaws, but notes that it is less successful in "offering a more positive construction of events" by itself.[19]

As it stands, Otto III allows readers to grasp the historiographic shortcomings of the past and understand the more thorough and perhaps more objective reevaluations that Althoff rightly claims historians of the present can and should offer.

Herbert Schutz writes the following on Otto III's personality and rulership:[20]

Despite his short reign, he has left a more enigmatic and interesting self-image than other rulers [...] Otto III was fourteen, when he was girt with the sword and declared of age, and when, without much ado, he took the reins of power from his grandmother in 994. One Heribert, chancellor for Italy and future archbishop of Cologne, may have planted the idea of a coronation in Rome in the young emperor's mind. Already on that occasion, he decided on a journey to Rome to obtain the imperial crown, to find a Byzantine bride and to forge an intertwining link with Italy. He was an enthusiast, but not a military man. During his very short personal rule of only seven years, conquest ceded to diplomacy and alliances. It is noteworthy that his foreign policy achieved lasting successes. In his dealings, he revealed himself a man, who respected conventions, but who also struck out with innovative initiatives of his own. not backed by tradition.[...] The image-makers of the day, with some hagiographic intent to color him as the saint on the imperial throne, may have done their share to present him in this light. Had "his" star not shone brightly in the daylight? His rich gifts to individuals and the personal favor of personal proximity, engaging in intimate conversations and confidentiality, drew him closer to the great minds of his day, while it accumulated personal and political capital. A11 inordinate number of testimonials of praise followed his reign [...] His support of art and architecture was to leave a lasting heritage. Otto III could be moody and driven by a sense of his own exalted person, he was drawn to distant places rather than to those nearby. He thought and planned globally.[...] He was a charismatic and most assertive personality with a Classical education, of ascetic piety and the conviction of a divinely ordained imperial role. With the tutelage of Bemward of Hildesheim and John Philagathos, the devoted servant of Otto II, Theophanu had raised a pious, artistic intellectual, Who appreciated spirituality and the beauty of the arts and Greco-Roman culture in particular.

Otto's (and Sylvester's) work in spreading Christianity and coopting a new group of nations (Slavic) into the framework of Europe, with their empire functioning, as some remark, as a "Byzantine-like presidency over a family of nations, centred on pope and emperor in Rome", has proved a lasting achievement.[21][22][23][24] The historian Ekkehard Eickhoff, himself also a diplomat, approves the reputation of the young ruler as a genius and linking his work in building a European peace order with the need for European unification today.[25][26]

Franke remarks that, during his short rule, he had not demonstrated a coherent military strategy, which allowed Boleslaw II of Bohemia and Lothair of France to launch campaigns into Meissen and Lotharingia. He focused on Italian campaigns and had achieved little concrete success. In the north, Slavic federations overran marches and bishoprics, leaving only Meissen and Lausitz east of the river of Elbe. An invasion into Saxony in 987 was only repulsed with Polish aid, and Henry the Quarrelsome was responsible for keeping Hungarians at bay.[27] Althoff remarks that while several (immense) campaigns during Otto's minority (with or without the king's participation – he began to personally participate in military campaigns at age six, in 986) were successful, a strategy of reconquest or improving former defensive positions was unclear. The 991 campaign that took Brandenburg seemed to be for the purpose of revenge for the 983 defeat. The 998 expedition to Rome, after which Johannes Philagathos and Crescentius the Younger were treated brutally (contrary to the medieval ideal of a merciful monarch and clementia), also seemed to be for revenge.[28] In Italy, he could rely upon the service of Count Hunerik or Unruoch (around 950–1010) of Teisterbant, a excellent commander who had received military education under the reign of Otto I. The 998 campaign was notable for the use of sophisticated siege engines and equipments. Bachrach opines that these were responsible for the successful siege of Sant' Angelo while Althoff claims that even with these machines, admittedly impressive technically and put under the direction of Margrave Ekkehard of Meissen, the rapidnesss of success seemed to be related to a complicated chain of events involving Crescentius's personal interaction with Otto III.[29][30][31] Benjamin Arnold opines that Otto III seemed to want to shift the focus of the Empire from the military, as it had been under his grandfather and father, to the ideological. Apparently in his earnest devotion, he thought that power had been bestowed on him for the purpose of expanding the Christian faith and preventing the world from imminent destruction.[32]

Legends[edit]

- The legend of Otto and the ghost of Charlemagne: According to legend, when opening Charlemagne's tomb, Otto saw his apparition, who told him that "Young and without heirs shalt thou depart from this world".[33]

A well known depiction of this legend is the fresco created by Alfred Rethel in 1847.[34][35] Wilhelm von Kaulbach produced a fresco depicting Otto III in the Tomb of Charlemagne (now destroyed; an illustration that imitates this work can be seen in the work Die Gartenlaube (1863) though.).[36]

There is a modern theory (created by Heribert Illig, born 1947) that Otto III, Sylvester II and Constantine VII of Byzantine were the ones who invented the entire Carolingian period and thus Charlemagne, but it is generally rejected by scholars.[37]

The Vienna Coronation Gospels is traditionally believed to be found by Otto III in Charlemagne's grave.[38] The so-called Sabre of Charlemagne is also traditionally regarded as having been discovered in this occasion.[39]

- The legend of Otto's death by poison: A popular legend, now considered unlikely, recounts that the young emperor was poisoned by Stephania (or Stefania), the beautiful widow of Crescentius.

The legend has received multiple depictions in literature and arts, including the 1866 five-act tragedy Stefania (written in verse) by Domenico Galati Fiorentini (1846–1901);[40] Sem Benelli's play Le nozze dei centauri ("The Marriage of the Centaurs", 1915 ), in which Otto (as a Christian) and Stefania (as a pagan woman) personify the Christian – pagan conflict;[41] the 1902 dramatic work Kaiser Otto III. by Heinrich Welzhofer;[42] Nathan Gallizier's 1907 novel The sorceress of Rome;[43] Hegedüs Géza's novella Szent Szilveszter éjszakája (Saint Sylvester's Eve, 1963), in which Gerbert was teacher to both Otto and Stephania, who loved Otto but poisoned him anyway;[44] William Wetmore Story's five-act tragedy Stephania;[45] Michael Field's 1892 Stephania.[46][47]

- The emperor is reputed to be very pious. Some of the stories involving his relationship with contemporary holy figures contain distorted or legendary elements (For artworks inspired by these episodes, see Visual arts). Saint Adalbert suppposedly resided day and night in the emperor's bedroom, like a "much-beloved chamberlain". instructing him in uninterrupted conversations on how to live virtuously as a mortal man. Althoff writes that reports do give evidences of the two men's friendship and that Otto was much affected by his martyrdom and later found many churches in honour of Adalbert.[48]

Depictions in arts[edit]

Works created under Otto III[edit]

- The Prayerbook of Otto III is the only extant prayerbook from the Ottonian era and also the only surviving one made for a tenth-century ruler, probably commissioned by Theophanu and Archbishop Willigs of Mainz. There are three full-page portraits of Otto himself, who was less than twelve when he received the manuscript.[49][50][51]

- The Gospels of Otto III was likely commissioned by the young emperor himself. A double-page miniature shows the emperor flanked by secular and religious dignitaries (connoting his status as standing above religious and temporal power) while receiving homage from Italia, Gallia, Germania and Slavia.[49][52][53]

- The Liuthar Gospels, commissioned by Otto III around 1000, shows the emperor being crowned by God. Ernst Kantorowicz suggests that the scroll, carried by the four evangelists and dividing the monarch's head from his body, represents the ruler's "two bodies" – his mortal body and his eternal authority granted by the divine.[54][55]

- The Bamberg Apocalypse, commissioned by or for either Otto or Henry II, shows the emperor seated on an elevated plane while being crown by Saints Peter and Paul, who were of the same size as him, with personifications of virtues offering their riches.[56][57]

- Abbo of Fleury wrote to the emperor letters in the form of complicated verses, in which he hoped Otto would hurry to the aid of Italy.[58]

- Leo of Vercelli wrote a panegyric, begin with a prayer that Rome would blossom under Otto. The poem praises the collaboration of the emperor and the pope. Görich notes that the poem expresses the Christian idea of four world empires rather than "a completely thought-out renovatio".[59]

- Gerbert of Aurillac (Pope Sylvester II), renowned scholar, scientist, and Otto's mentor, often wrote verses to him and Otto sometimes replied in verses too, as in 997:[60][61][62]

No verses have I ever made,

Nor ever notice to them paid

While, then ,I have them now in mind,

And in them lively solace find,

As many men as live in Gaul,

So many songs I'll send for all!

- The Cross of Lothair is possibly created for Otto III. It was a revered processional cross in the Late Ottonian period. The cross links the Ottonian dynasty with the Carolingian dynasty and the Ancient Roman Empire.[63][64]

Visual arts[edit]

- Otto III's portrait in the Kaisersaal, Frankfurt am Main, was painted by Joseph Anton Settegast. This is part of a series depicting emperors who reigned from 768 to 1806 (created from 1839 to 1853) in the Kaisersaal in Frankfurt am Main.[65]

- Fra Angelico (1395 – 1455) painted the scene of Saint Romuald rebuking Otto for the murder of Crescentius.[66]

- The fifteenth century Netherlandish painter Dirk Bouts painted the Justice of Emperor Otto III. Rosalind Mutter notes that the painting is not for the faint-hearted: "In these paintings torture is carried out with a philosophic detachment that is positively gruesome."[67] The story associated with the painting is as the following: "The wife of Emperor Otto III made sexual advances to a married German count, but when he rejected her, she falsely accused him in revenge, and Otto Ill had him beheaded. The count's widow sought to prove her husband's innocence and underwent ordeal by red-hot iron, a medieval practice to establish the truth. The widow held the red-hot iron bar and remained unharmed, thus revealing the empress's treachery. To atone for his wrongful judgment, Otto sentenced his wife to be burned at the stake."[68]

- The oil painting Giustizia dell'Imperatore Ottone, often attributed to Luca Penni, is about the same story.[69]

Italian visual arts tend to depict the relationship between Otto III and contemporary Saints, as seen in the works of the following artists:

- The seventeenth century painter Drago Giovanni painted the Ottone III fa visita a San Romualdo nella sua cella dell'Eremo del Perèo presso Ravenna, depicting the meeting between Otto III and Saint Romuald in Ravenna.[70]

- Giuseppe Castellano (around 1686 to 1725) painted the Ottone III chiede il corpo di San Bartolomeo.[71]

- Between 1697 and 1698, Giuseppe Malatesta Garuffi (died in 1727) painted the San Romualdo chiede clemenza a Ottone III (Saint Romuald asked for clemency from Otto III).[72]

- Gian Antonio Fumiani, around 1705-1710, painted the Visita dell'imperatore Ottone III (Visit by Emperor Otto III for the Diocese in Venice.[73]

- In 1747, Jacopo Marieschi painted San Romualdo e l'Imperatore Ottone III (Saint Romuald and Emperor Otto III).[74][75]

- In 1772, Tommaso Righi painted the Ottone III confessa a San Romulado l'uccisione del senatore Crescenzio (Otto III confesses to Saint Romuald about the killing of Senator Crescentius).[76]

- In 1781, Vincenzo Milione painted San Romualdo incontra Ottone III.[77]

- Antonio Capellan (before 1740-1793) created the etching Incontro di San Nilo con Ottone III.[78]

- In 1835, Angelo Quadrini created the fresco San Romualdo intercede per i tiburtini presso l'imperatore Ottone III (Saint Romuald intercessed with Emperor Otto III" in piazza del Governo, Tivoli.[80]

There are several Polish depictions of Otto III together with Boleslaw the Brave.

- The Coronation of the First King of Poland (1889) by Jan Matejko is an iconic painting, depicting the symbolic coronation of Boleslaw the Brave by Otto in 1000.[81][82]

- In 1835, Edward Brzozowski painted the scene of Boleslaw the Brave and Otto III at the Grave of St Wojciech.[83]

- Cesare Maccari (1840 – 1919) painted L'imperatore Ottone III consegna ai giudici i libri giustinianei depicting Emperor Otto III, who provided his judges with the Corpus Iuris Civilis (Rome, between 996 and 1002). Here, "Otto III tries to restore Roman law, using it as a tool for the Renovatio Imperii Romanorum. In order to more firmly establish his own presidential power, he set about building a new imperial palace on the Palatine hill, rather than follow the blueprint of his Carolingian predecessors who built near the site of St. Peter’s Basilica. He hoped the architecture would establish an urban connection between his empire and the ancient one".[84][85]

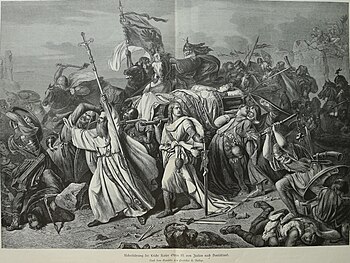

- The 1883 painting Die Leiche Kaiser Otto III . wird unter Kampf über die Alpen geführt or Die Überführung der Leiche Kaiser Ottos III. über die Alpen (The conveying of Otto III's dead body over the Alps) is an early important painting of Albert Baur (link to the painting, preserved by the Kulturstiftung Sachsen-Anhalt - Kunstmuseum Moritzburg Halle (Saale)).[86][87]

- At the Rathaus of Quedlinburg, a bronze plaque with relief depicting King Otto III on his throne was created in 1994, in commemoration of the year of 994, when "he granted the right of market, tax and coining and established the first market place to the north of the castle hill of Quedlinburg".[88]

- In 1998, the artist Paolo Maiani dedicated various frescoes to mark the centennial of Logge di Pavana, among them one depicting the scene of the donation by Otto III to the bishop of Pistoia.[89]

Theater[edit]

- Ottone, a tragedia per musica, with music attributed to Carlo Francesco Pollarolo and text by Girolamo Frigimelica, is a 1694 Venetian opera. In this work, Otto III killed a count that his wife Mary of Aragon loved, but the count happened to be his son. The work is dedicated to Ernst August, Duke of Brunswick.[92]

- Kaiser Otto der Dritte is a 1783 trauerspiel by Basilius von Ramdohr[93]

- Gustav Anton von Seckendorff published Otto III.: Der gutgeartete Jüngling : ein Trauerspiel in fünf Aufzügen in Torgau, 1805.[94][95]

- Adolf Friedrich Furchau published Kaiser Otto der Dritte. Trauerspiel. in Göttingen‚ 1809.[94]

- Friedrich von Uechtritz published Rom und Otto III. Ein historische trauerspiel in Berlin, 1823.[94]

- In 1840, Felix Mendelssohn wrote Otto III., or Otto III's Pilgrimage to Rome, and Death, one of the historical operas he wrote in the last years of his life.[96][97]

- Julius Mosen published Kaiser Otto III. Historische tragödie. in Stuttgart, 1842.[94]

- Kaiser Otto III.: Trauerspiel in fünf Aufzügen is a 1863 work (Trauerspiel means "mourning play", is related to but does not equate to "tragedy"[98]) by Karl Biedermann[99]

- Kaiser Otto der Dritte: Schauspiel in fünf Aufzügen was composed by Friedrich von Hindersin in 1858.[100][101]

- Kaiser Otto der Dritte: Drama was written by Julius Hillebrand in 1891.[102]

- Kaiser Otto der Dritte: ein Trauerspiel in fünf Aufzügen is a 1901 work by Paul Schmidt.[103]

- Kaiser Otto der Dritte: Schauspiel in fünf Aufrügen was published by Alberta von Puttkamer in 1914.[104]

Poems[edit]

- In the eleventh century manuscript Cambridge Songs (probably copied from a German source), there are the poem De Henrico, that is about Otto and Henry II, and the song Modus Ottino, which is a panegyric on Otto I, Otto II and Otto III.[105][106]

- Klagelied Kaiser Otto des Dritten (Eulogy for Emperor Otto III, 1833) by August Graf von Platen is an early work that reproaches the emperor on behalf of an nationalist agenda.[107]

Novels[edit]

- Der Kaiser Otto III. is a 1951 historical novel about the life of the emperor, written by historian and writer Albert H. Rausch (pseudonym Henry Benrath).[109]

- The devil's pope is a 2012 novel by Adrian Lumenti about Gerbert of Aurillac and Otto.[110]

- Rache: Historischer Roman um die Thronfolge Kaiser Ottos III. is a 2013 novel by Horst Petersen about the situation from Otto's death without an heir.[111]

- Das Siegel der Macht is a 2019 novel by Monika Dettwiler about "Emperor Otto III, the first German pope, Gregory V and a young messenger who wanted to solve a murder case and found the love of his life".[112]

- Die Geliebte des Kaisers is a 2020 novel by the Augsburg writer Peter Dempf. The story is about Mena, who loved Otto and was told by the dying emperor to bring his heart and his unborn child back to Augsburg.[113]

Documentaries[edit]

- His life is depicted in the ARD documentary Kaiser Otto III. Erneuerer des Reiches (2010). It is shown how the young emperor quickly changed Europe through friendly ties with newly Christianized realms such as Poland, Hungary and Venice as how imperial policy affected normal people and monks.[114]

Commemoration[edit]

In 2002, on the 1000th commemoration of his death, a square in Kessel (Otto was born near Kessel) was named after him and commemoration boards about his life have been set up there.[115][116]

On 12 March 2000, the presidents of Germany, Poland, Lithuania, Hungary and Slovakia came to Gniezno to mark the 1000th anniversary of the meeting between Otto III and Boleslaw Chrobry in Gniezno.[117]

See also[edit]

- Prayerbook of Otto III

- Gospels of Otto III

- Liuthar Gospels

- Bamberg Apocalypse

- Cultural depictions of Adelaide of Italy

- Cultural depictions of Theophanu

- Cultural depictions of Otto the Great

- Cultural depictions of Conrad II, Holy Roman Emperor

- Cultural depictions of Frederick I, Holy Roman Emperor

- Cultural depictions of Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor

- Cultural depictions of Charles IV, Holy Roman Emperor

- Cultural depictions of Sigismund, Holy Roman Emperor

- Cultural depictions of Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor

- Cultural depictions of Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor

External links[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Va-t-on un jour oublier un peu Schramm, dont l’arbre cache la forêt de ceux qui s'intéressent à Otton III? Après M. Uhlirz, H. Ludat, H. Thomas, J. Fried, K. Görich, quelqu’un va—t—il se décider à refaire l’histoire d’Otton III, non pas pour mettre en cause les idées des devanciers, mais pour reprendre posément un grand règne, le gouvernement d’un jeune empereur génial, un très grand moment de l’histoire de l’empire germanique, toujours esquissé dans les biographies des princes, jamais repris dans son ensemble?

Bibliography and further reading[edit]

- Althoff, Gerd (1 November 2010). Otto III. Penn State Press. ISBN 978-0-271-04618-1. Retrieved 25 February 2022.

- Beuckers, Klaus Gereon; Cramer, Johannes; Imhof, Michael (2002). Die Ottonen: Kunst, Architektur, Geschichte (in German). Michael Imhof Verlag. ISBN 978-3-932526-61-9. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- Johann Friedrich Böhmer, Mathilde Uhlirz: Regesta Imperii II, 3. Die Regesten des Kaiserreiches unter Otto III. Wien u. a. 1956.

- Braak, Menno ter (1928). Kaiser Otto III.: Ideal und praxis im fruehen mittelalter (in German). J. Clausen.

- The Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica. "Otto III Holy Roman emperor Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 4 May 2022.

- Garrison, Eliza (5 July 2017). Ottonian Imperial Art and Portraiture: The Artistic Patronage of Otto III and Henry II. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-351-55540-1. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- Giesebrecht, Wilhelm : von (1872). Geschichte der deutschen Kaiserzeit von Wilhelm von Giesebrecht: Staufer und Welfen (in German). Schwetschke. Retrieved 18 March 2022.

- Görich, Knut (1993). Otto III., Romanus Saxonicus et Italicus : kaiserliche Rompolitik und sächsische Historiographie. Sigmaringen: J. Thorbecke. ISBN 9783799504676.

- Jantzen, Hans (1990). Ottonische Kunst (in German). Reimer. ISBN 978-3-496-01069-2. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- Keller, Hagen (2001). Die Ottonen (in German). C.H.Beck. ISBN 978-3-406-44746-4. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- Theodor Sickel (Hrsg.): Diplomata 13: Die Urkunden Otto des II. und Otto des III. (Ottonis II. et Ottonis III. Diplomata). Hannover 1893 (Monumenta Germaniae Historica, Digitalisat)

- Schramm, Percy Ernst (1931). Otto III (in Italian). Seidel & Sohn. Retrieved 15 March 2022.

References[edit]

- ^ Althoff 2010, p. 74.

- ^ Althoff 2010, p. 1.

- ^ a b Althoff 2010, pp. 11, 148.

- ^ Bryce, James (1866). The Holy Roman Empire. MacMillan and Company. p. 228. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- ^ Bideleux, Robert; Jeffries, Ian (10 April 2006). A History of Eastern Europe: Crisis and Change. Routledge. p. 119. ISBN 978-1-134-71985-3. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- ^ Lewis, Archibald Ross (1988). Nomads and Crusaders, A.D. 1000-1368. Georgetown University Press. p. 83. ISBN 978-0-253-34787-9. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- ^ Emmerson, Richard K. (18 October 2013). Key Figures in Medieval Europe: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. p. 497. ISBN 978-1-136-77518-5. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- ^ Muldoon, J. (19 August 1999). Empire and Order: The Concept of Empire, 800–1800. Springer. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-230-51223-8. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- ^ Diggelmann, Lindsay (2005). "Otto III (review)". Parergon. 22 (1): 185–187. doi:10.1353/pgn.2005.0019. S2CID 144996570. Retrieved 18 March 2022.

- ^ Beuckers, Klaus Gereon (1993). Die Ezzonen und ihre Stiftungen: eine Untersuchung zur Stiftungstätigkeit im 11. Jahrhundert (in German). LIT Verlag Münster. p. 104. ISBN 978-3-89473-953-9. Retrieved 4 May 2022.

- ^ Althoff 2010, p. 2.

- ^ Péter 2012, p. 21.

- ^ Péter, Laszlo (23 March 2012). Hungary's Long Nineteenth Century: Constitutional and Democratic Traditions in a European Perspective. BRILL. p. 21. ISBN 978-90-04-22421-6. Retrieved 15 March 2022.

- ^ Althoff 2010, p. 4.

- ^ Althoff 2010, p. 6.

- ^ Urbańczyk, Przemysław (2001). Europe Around the Year 1000. Wydawn. DiG. pp. 469–483. ISBN 978-83-7181-211-8.

- ^ Jeep, John M. (5 July 2017). Routledge Revivals: Medieval Germany (2001): An Encyclopedia. Taylor & Francis. p. 650. ISBN 978-1-351-66540-7.

- ^ Parisse, Michel (1997). "Knut Görich, Otto III. Romanus Saxonicus et Italicus. Kaiserliche Rompolitik und sächsische Historiographie, 1993". Francia (in French). 24 (1): 215–216. doi:10.11588/fr.1997.1.60713. ISSN 2569-5452. Retrieved 18 March 2022.

- ^ Hofmann, Julie A. "Hofmann on Althoff, 'Otto III' H-German | H-Net". networks.h-net.org. Retrieved 18 March 2022.

- ^ Schutz, Herbert (19 February 2010). The Medieval Empire in Central Europe: Dynastic Continuity in the Post-Carolingian Frankish Realm, 900-1300. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 83. ISBN 978-1-4438-2035-6. Retrieved 4 May 2022.

- ^ Fried, Johannes (13 January 2015). The Middle Ages. Harvard University Press. p. 138. ISBN 978-0-674-74467-7. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- ^ Rowland, Christopher; Barton, John (2002). Apocalyptic in History and Tradition. Bloomsbury Academic. p. 173. ISBN 978-0-8264-6208-4. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- ^ Arnason, Johann P.; Wittrock, Björn (1 January 2005). Eurasian Transformations, Tenth to Thirteenth Centuries: Crystallizations, Divergences, Renaissances. BRILL. p. 100. ISBN 978-90-474-1467-4. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- ^ German Polish Dialogue: Letters of the Polish and German Bishops and International Statements. Ed. Atlantic-Forum. 1966. p. 9. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- ^ Merkur (in German). E. Klett Verlag. 2000. p. 77. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- ^ "Kaiser Otto III: Die erste Jahrtausendwende und die Entfaltung Europas". Deutschlandfunk (in German). Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- ^ Franke, Daviod P. (2010). "Narrative". In Rogers, Clifford J.; Caferro, William; Reid, Shelley (eds.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Medieval Warfare and Military Technology. Oxford University Press. p. 169. ISBN 978-0-19-533403-6. Retrieved 31 July 2022.

- ^ Althoff 2010, pp. 47, 73, 75.

- ^ Althoff 2010, pp. 75–77.

- ^ Bachrach, David S. (2014). Warfare in Tenth-Century Germany. Boydell & Brewer Ltd. p. 115. ISBN 978-1-84383-927-9. Retrieved 16 August 2022.

- ^ Bachrach, David (2008). "The Military Organization of Ottonian Germany, c. 900–1018: The Views of Bishop Thietmar of Merseburg". The Journal of Military History. 72 (4): 1061–1088. doi:10.1353/jmh.0.0152.

- ^ Arnold, Benjamin (9 June 1997). Medieval Germany, 500–1300: A Political Interpretation. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 89. ISBN 978-1-349-25677-8. Retrieved 16 August 2022.

- ^ Zimmermann, Wilhelm (1878). A Popular History of Germany: From the Earliest Period to the Present Day. H. J. Johnson. p. 826. Retrieved 15 March 2022.

- ^ Garver, Valerie L.; Phelan, Owen M. (8 April 2016). Rome and Religion in the Medieval World: Studies in Honor of Thomas F.X. Noble. Routledge. p. 265. ISBN 978-1-317-06124-3. Retrieved 15 March 2022.

- ^ Frech, Volker (31 January 2001). Lebende Bilder und Musik am Beispiel der Düsseldorfer Kultur (Thesis) (in German). diplom.de. p. 77. ISBN 978-3-8324-3062-7. Retrieved 15 March 2022.

- ^ Wieczorek, Alfried; Hinz, Hans-Martin (2000). Europe's Centre Around AD 1000. Theiss. p. 630. ISBN 978-3-8062-1549-6.

- ^ Proud, James (14 May 2020). This Book Will Make You Sh!t Yourself: Unexplained Events, Shocking Conspiracy Theories and Unbelievable Truths to Scare the Cr*p Out of You. Summersdale Publishers Limited. p. 47. ISBN 978-1-78783-807-9. Retrieved 26 July 2022.

- ^ Wooding, Professor Jonathan (2 March 2020). Prophecy, Fate and Memory in the Early Medieval Celtic World. Sydney University Press. p. 83. ISBN 978-1-74332-679-4. Retrieved 26 July 2022.

- ^ Steingräber, Erich (1968). Royal Treasures. Macmillan. p. 47. Retrieved 26 July 2022.

- ^ Galati–Fiorentini, Domenico (1867). Opere drammatiche. vol. 1. (Stefania, tragedia in cinque atti [and in verse].) (in Italian). p. 39. Retrieved 15 March 2022.

- ^ MacClintock, Lander (1920). The Contemporary Drama of Italy. Little, Brown. p. 214. Retrieved 15 March 2022.

- ^ Welzhofer, Heinrich (1902). Kaiser Otto III.: Drama in vier akten (in German). E. Pierlon.

- ^ Nield, Jonathan (1911). A Guide to the Best Historical Novels and Tales. E. Mathews. p. 261. Retrieved 15 March 2022.

- ^ Hegedüs, Géza (1963). Szent Szilveszter éjszakája (in Hungarian). Magvető.

- ^ Story, William Wetmore (1875). Stephania: A Tragedy in Five Acts, with a Prologue. W. Blackwood and Sons. Retrieved 15 March 2022.

- ^ Field, Michael (1892). Stephania: A Trialogue. E. Mathews & John Lane. Retrieved 15 March 2022.

- ^ Burroughs, Catherine (3 September 2018). Closet Drama: History, Theory, Form. Routledge. p. 146. ISBN 978-1-351-60693-6. Retrieved 15 March 2022.

- ^ Althoff 2010, p. 70.

- ^ a b "Tracing Otto III's Life in Three Manuscripts". Facsimile Finder Blog. 12 June 2020. Retrieved 4 May 2022.

- ^ Jeep, John M. (5 July 2017). Routledge Revivals: Medieval Germany (2001): An Encyclopedia. Routledge. p. 1780. ISBN 978-1-351-66539-1. Retrieved 4 May 2022.

- ^ Greer, Sarah; Hicklin, Alice; Esders, Stefan (16 October 2019). Using and Not Using the Past after the Carolingian Empire: c. 900–c.1050. Routledge. p. 149. ISBN 978-0-429-68303-9. Retrieved 4 May 2022.

- ^ Benton, Janetta Rebold (2009). Materials, Methods, and Masterpieces of Medieval Art. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-275-99418-1. Retrieved 4 May 2022.

- ^ Brandt, Bettina (2010). Germania und ihre Söhne: Repräsentationen von Nation, Geschlecht und Politik in der Moderne (in German). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. pp. 36–37. ISBN 978-3-525-36710-0. Retrieved 4 May 2022.

- ^ Woodacre, Elena; Dean, Lucinda H. S.; Jones, Chris; Rohr, Zita; Martin, Russell (12 June 2019). The Routledge History of Monarchy. Routledge. p. 222. ISBN 978-1-351-78730-7. Retrieved 4 May 2022.

- ^ Karkov, Catherine E. (2004). The Ruler Portraits of Anglo-Saxon England. Boydell Press. p. 95. ISBN 978-1-84383-059-7. Retrieved 4 May 2022.

- ^ Davids, Adelbert (15 August 2002). The Empress Theophano: Byzantium and the West at the Turn of the First Millennium. Cambridge University Press. p. 176. ISBN 978-0-521-52467-4. Retrieved 4 May 2022.

- ^ Wangerin, Laura (2019). Kingship and Justice in the Ottonian Empire. University of Michigan Press. p. 122. ISBN 978-0-472-13139-6. Retrieved 4 May 2022.

- ^ Duckett, Eleanor Shipley (1967). Death and Life in the Tenth Century. University of Michigan Press. p. 247. ISBN 978-0-472-06172-3. Retrieved 25 May 2022.

- ^ Althoff 2010, p. 84.

- ^ McDonald, William C.; Goebel, Ulrich (1973). German Medieval Literary Patronage from Charlemagne to Maximilian I: A Critical Commentary with Special Emphasis on Imperial Promotion of Literature. Rodopi. p. 41. Retrieved 25 May 2022.

- ^ Duckett 1967, p. 247.

- ^ Davis, Henry William Carless (1911). Medieval Europe. H. Holt. Retrieved 25 May 2022.

- ^ Schutz, Herbert (19 February 2010). The Medieval Empire in Central Europe: Dynastic Continuity in the Post-Carolingian Frankish Realm, 900-1300. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 119. ISBN 978-1-4438-2035-6. Retrieved 26 July 2022.

- ^ Calkins, Robert G. (1985). Monuments of Medieval Art. Cornell University Press. p. 115. ISBN 978-0-8014-9306-5. Retrieved 26 July 2022.

- ^ Althoff, Gerd (1996). Otto der Dritte (in German). Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft. p. 182. ISBN 978-3-534-11274-6. Retrieved 18 March 2022.

- ^ Baedeker (Firm), Karl (1914). Belgien und Holland nebst Luxemburg: Handbuch für Reisende (in German). Verlag von Karl Baedeker. p. 136. Retrieved 18 March 2022.

- ^ Mutter, Rosalind (February 2008). Early Netherlandish Painting. Crescent Moon Publishing. p. 90. ISBN 978-1-86171-165-6. Retrieved 18 March 2022.

- ^ Roberts, Helene E. (5 September 2013). Encyclopedia of Comparative Iconography: Themes Depicted in Works of Art. Routledge. p. 1185. ISBN 978-1-136-78792-8. Retrieved 18 March 2022.

- ^ Ghisi, Giorgio; Lewis, Michal; Lewis, R. E. (1985). The Engravings of Giorgio Ghisi. Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 113. ISBN 978-0-87099-397-8. Retrieved 18 July 2023.

- ^ "Ottone III fa visita a San Romualdo nella sua cella dell'Eremo del". catalogo.beniculturali.it. Retrieved 11 May 2022.

- ^ "Ottone III chiede il corpo di San Bartolomeo dipinto". catalogo.beniculturali.it. Retrieved 11 May 2022.

- ^ "San Romualdo chiede clemenza a Ottone III dipinto, 1697 - 1698". catalogo.beniculturali.it. Retrieved 11 May 2022.

- ^ "Fumiani G. (1705-1710), Visita dell'imperatore Ottone III". BeWeB - Beni Ecclesiastici in Web (in Italian).

- ^ ""In vita et post mortem miráculis clarus, spíritu étiam prophetíæ non cáruit. Scalam a terra cælum pertingéntem, in similitúdinem Jacob Patriárchæ, per quam hómines in veste cándida ascendébant et descendébant, per visum conspéxit; eóque Camaldulénses mónachos, quorum institúti auctor fuit, designári mirabíliter agnóvit" (Lect. VI – II Noct.) - SANCTI ROMUALDI, ABBATIS CAMALDULENSIS ORDINIS FUNDATORIS ET CONFESSORIS". Scuola Ecclesia Mater (in Italian). Retrieved 11 May 2022.

- ^ "San Romualdo e l'Imperatore Ottone III dipinto, ca 1747 - ca 1747". catalogo.beniculturali.it. Retrieved 11 May 2022.

- ^ "Ottone III confessa a San Romulado l'uccisione del senatore Crescen". catalogo.beniculturali.it. Retrieved 11 May 2022.

- ^ "San Romualdo incontra Ottone III dipinto, 1781 - 1781". catalogo.beniculturali.it. Retrieved 11 May 2022.

- ^ "incontro di San Nilo con Ottone III stampa, 1700 - 1783". catalogo.beniculturali.it. Retrieved 11 May 2022.

- ^ "History of civilization in Poland. Coronation of the first king, 1001 year, 1889, 105×79 cm by Jan Matejko: History, Analysis & Facts". Arthive. Retrieved 4 May 2022.

- ^ "San Romualdo intercede per i tiburtini presso l'imperatore Ottone I". catalogo.beniculturali.it. Retrieved 11 May 2022.

- ^ Uniwersytet Warszawski; Instytut Historyczny, Polski; Komitet do Spraw UNESCO (2000). Quaestiones Medii Aevi Novae. Wydawn. DiG. p. 126. Retrieved 4 May 2022.

- ^ Dabrowski, Patrice M. (1 October 2014). Poland: The First Thousand Years. Cornell University Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-1-5017-5740-2. Retrieved 4 May 2022.

- ^ Bremer, T. (1 April 2008). Religion and the Conceptual Boundary in Central and Eastern Europe: Encounters of Faiths. Springer. p. 133. ISBN 978-0-230-59002-1. Retrieved 4 May 2022.

- ^ Gialdroni, Stefania (19 March 2019). "(Hi)stories of Roman Law. Cesare Maccari's frescoes in the Aula Massima of the Italian Supreme Court". Forum Historiae Iuris (in German). Retrieved 4 May 2022.

- ^ "Corte di Cassazione - Pitture". www.cortedicassazione.it. Retrieved 4 May 2022.

- ^ Schmidt, Hans-Werner (1985). Die Förderung des vaterländischen Geschichtsbildes durch die Verbindung für historische Kunst, 1854-1933 (in German). Jonas. p. 82. ISBN 978-3-922561-33-0. Retrieved 11 May 2022.

- ^ "Die Überführung der Leiche Kaiser Ottos III. über die Alpen". www.akg-images.com. Retrieved 11 May 2022.

- ^ "Quedlinburg - Römisch-deutscher König Otto III". statues.vanderkrogt.net. Retrieved 4 May 2022.

- ^ "Le canzoni di Guccini nell'arte di Maiani - Cronaca - lanazione.it". La Nazione (in Italian). 29 July 2022. Retrieved 16 August 2022.

- ^ Jenkins, Simon (4 November 2021). Europe's 100 Best Cathedrals. Penguin Books Limited. p. 103. ISBN 978-0-241-98956-2. Retrieved 18 July 2023.

- ^ Didron, Adolphe Napoléon (1886). Christian Iconography. G. Bell. p. 74. Retrieved 18 July 2023.

- ^ Selfridge-Field, Eleanor (2007). A New Chronology of Venetian Opera and Related Genres, 1660-1760. Stanford University Press. p. 207. ISBN 978-0-8047-4437-9.

- ^ Ramdohr, Friedrich Wilhelm Basilius von (1783). Kaiser Otto der Dritte (in German). Dieterich. Retrieved 18 July 2023.

- ^ a b c d Library, Boston Public (1895). Bulletin. p. 176. Retrieved 23 August 2022.

- ^ Seckendorff, Gustav Anton von (1805). Otto III.: Der gutgeartete Jüngling : ein Trauerspiel in fünf Aufzügen (in German). Kurz.

- ^ Cooper, John Michael; Prandi, Julie D. (2002). The Mendelssohns: Their Music in History. Oxford University Press. p. 195. ISBN 978-0-19-816723-5.

- ^ Devrient, Eduard (1869). My Recollections of Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy and His Letters to Me. Richard Bentley. p. 41. Retrieved 4 May 2022.

- ^ Fenves, Peter David (2001). Arresting Language: From Leibniz to Benjamin. Stanford University Press. p. 236. ISBN 978-0-8047-3960-3. Retrieved 18 March 2022.

- ^ Biedermann, Karl (1863). Kaiser Otto III.: Trauerspiel in fünf Aufzügen (in German). Brockhaus.

- ^ Hindersin, Friedrich von (1886). Kaiser Otto der Dritte: Schauspiel in fünf Aufzügen (in German). Naumann.

- ^ Bibliothek, Rothschild'sche (1904). Verzeichnis der Bücher (in German). Knauer. p. 290. Retrieved 23 August 2022.

- ^ Hillebrand, Julius (1891). Kaiser Otto der Dritte: Drama (in German). Finsterlin.

- ^ Schmidt, Paul (1901). Kaiser Otto der Dritte: ein Trauerspiel in fünf Aufzügen (in German). Naumann.

- ^ Puttkamer, Alberta von (1914). Kaiser Otto der Dritte: Schauspiel in fünf Aufrügen von A. von Puttkamer (in German). Flemming.

- ^ Gibbs, Marion; Johnson, Sidney M. (11 September 2002). Medieval German Literature: A Companion. Routledge. p. 53. ISBN 978-1-135-95678-3. Retrieved 4 May 2022.

- ^ Harrington, K. P.; Pucci, Joseph (10 November 1997). Medieval Latin: Second Edition (in Latin). University of Chicago Press. p. 399. ISBN 978-0-226-31713-7. Retrieved 4 May 2022.

- ^ Althoff 2010, p. 12.

- ^ Illustrirte Zeitung (in German). Weber. 1863. ISBN 978-3-89131-349-7.

- ^ German Book News: Reports on German Writing and Publishing. 1949. Retrieved 25 May 2022.

- ^ Lumenti, Adrian (1 February 2012). The Devil's Pope. Monsoon Books. ISBN 978-981-4358-70-5. Retrieved 18 July 2023.

- ^ Petersen, Horst (2013). Rache: ein historischer Roman um die Thronfolge Kaiser Ottos III (1. Aufl ed.). Berlin: Pro Business. ISBN 978-3863865184.

- ^ Dettwiler, Monika (11 January 2019). Das Siegel der Macht: Historischer Roman (in German). Piper Schicksalsvoll. ISBN 978-3-492-98400-3. Retrieved 25 May 2022.

- ^ Dempf, Peter (2019). Die Geliebte des Kaisers: historischer Roman. Köln: Bastei Lübbe Taschenbuch. p. 23. ISBN 978-3404179459. Retrieved 18 July 2023.

- ^ Germany, programm ARD de-ARD Play-Out-Center Potsdam, Potsdam. "Kaiser Otto III". programm.ARD.de. Retrieved 25 May 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Spargeldorf Kessel - Kaiser-Otto-Platz". spargeldorf-kessel.de. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- ^ "Der Kaiser Otto Platz in Kessel wird mit einem Fest eröffnet" (in German). 7 April 2022. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- ^ Mikołajczak, Aleksander Wojciech (2003). Gnieźnieńska księga tysiąclecia. Gaudentinum. p. 202. ISBN 978-83-89270-12-2. Retrieved 30 May 2022.