Climate change in Louisiana encompasses the effects of climate change, attributed to man-made increases in atmospheric carbon dioxide, in the U.S. state of Louisiana.

Studies show that Louisiana is among a string of "Deep South" states that will experience the worst effects of climate change.[1] According to the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), "[i]n the coming decades, Louisiana will become warmer, and both floods and droughts may become more severe. Unlike most of the nation, Louisiana did not become warmer during the last century. But soils have become drier, annual rainfall has increased, more rain arrives in heavy downpours, and sea level is rising. The changing climate is likely to increase damages from floods, reduce crop yields and harm fisheries, increase the number of unpleasantly hot days, and increase the risk of heat stroke and other heat-related illnesses".[2]

Louisiana is expected to be the site of substantial climate refugee challenge, because of the loss of coastline, changing environmental conditions that make the humid coastal ecosystems not easily habitable, and declining economic viability of industries in that geography.[3]

In 2021, Louisiana experienced a substantial impact from Hurricane Ida, which was noted as having characteristics that are probably more common in a warmer climate: the intensity, the rapid intensification, and the amount of rainfall over land.[4]

Rising seas and retreating shores[edit]

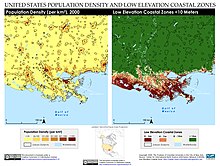

According to the EPA: "Rising sea level is likely to accelerate coastal erosion caused today by sinking land and human activities. The sediment washing down the Mississippi River created the river delta that comprises most of coastal Louisiana. These sediments gradually compact, so the land sinks about one inch every three years. Historically, the river would occasionally overflow its banks and deposit enough new sediment to allow the land surface to keep pace with rising sea level and the delta’s tendency to sink. But today, river levees, navigation channels, and other human activities thwart this natural land-building process, so coastal lands are being submerged. Louisiana has been losing about 25 square miles of land per year in recent decades".[2]

The EPA further reports: "If temperatures continue to warm, sea level is likely to rise one to three feet during the next century. Rising sea level has the same effect as sinking land, so changing climate is likely to accelerate coastal erosion and land loss. Federal, state, and local governments have ongoing projects to slow land loss in Louisiana, but if the sea rises more rapidly in the future, these efforts will become increasingly difficult".[2]

Tropical storms[edit]

According to the EPA, "tropical storms and hurricanes have become more intense during the past 20 years. Although warming oceans provide these storms with more potential energy, scientists are not sure whether the recent intensification reflects a long-term trend. Nevertheless, hurricane wind speeds and rainfall rates are likely to increase as the climate continues to warm".[2] According to the Fifth National Climate Assessment published in 2023, coastal states including California, Florida, Louisiana, and Texas are experiencing "more significant storms and extreme swings in precipitation".[5]

Climate change impacts on tropical storms, have already increased damage to cities like New Orleans, causing climate migration. For example, New Orleans has 60,000 fewer people than it did before Hurricane Katrina.[3]

Increased flooding[edit]

"Whether or not tropical storms become more frequent, rising sea level makes low-lying areas more prone to flooding. Many coastal roads, railways, airports, and oil and gas facilities are vulnerable to the impacts of storms and sea level rise. Louisiana is especially vulnerable, because much of New Orleans and other populated areas are below sea level, protected by levees and pumping systems that remove rainwater, which cannot drain naturally. With a higher sea level, these levees may be overtopped more readily during storms.

Severe flooding can disrupt the economy of a city by inducing people to move away, which occurred after Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans. The greater flood risk is also likely to increase flood insurance rates".[2]

The EPA notes that "changing climate is also likely to increase the risk of inland flooding. Since 1958, the amount of precipitation falling during heavy rainstorms has increased by 27 percent in the Southeast, and the trend toward increasingly heavy rainstorms is likely to continue. Moreover, the amount of rainfall in the Midwest is also likely to increase, which could worsen flooding in Louisiana, because most of the Midwest drains into the Mississippi River".[2]

The EPA further reports that "the Port of New Orleans is vulnerable to river floods that shut down traffic on the Mississippi River, as well as coastal storms that can flood port facilities. In 2011, high water levels on the Mississippi River led the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to divert water through the Morganza Spillway to the Atchafalaya River to prevent serious flooding of Baton Rouge and New Orleans. The resulting high water on the Atchafalaya flooded small towns and about 1,000 square miles of agricultural land, and required temporary levees to protect Morgan City. Although major flooding on the Mississippi River was avoided, high water levels still caused a barge collision that led the Corps to close the river near Baton Rouge for four days".[2]

Agriculture, forests, and fisheries[edit]

According to the EPA, "changing climate will have both harmful and beneficial effects on farming. Seventy years from now, Louisiana is likely to have 35 to 70 days with temperatures above 95°F, compared with about 15 days today. Even during the next few decades, hotter summers are likely to reduce yields of corn and rice. But higher concentrations of atmospheric carbon dioxide increase crop yields, and that fertilizing effect is likely to offset the harmful effects of heat on soybeans and cotton—if adequate water is available. On farms without irrigation, however, increasingly severe droughts could cause more crop failures.

Higher temperatures are also likely to reduce livestock productivity, because heat stress disrupts the animals’ metabolism. Higher temperatures and changes in rainfall are unlikely to substantially reduce forest cover in Louisiana, although the composition of trees in the forests may change. More droughts would reduce forest productivity, and climate change is also likely to increase the damage from insects and disease. But longer growing seasons and increased concentrations of carbon dioxide could more than offset the losses from those factors. Forests cover about half of the state, with loblolly-shortleaf pine forests most common outside of wetland areas. Changing climate may cause the loblolly and shortleaf pine trees to give way to oak-pine forests".[2]

The EPA further reports that "rising sea level and higher temperatures threaten Louisiana's fisheries. Coastal wetlands account for most of the land that the state has been losing. Those wetlands support shrimp, oyster, crab, crawfish, menhaden, and other fisheries–about 75 percent of the state’s total commercial fisheries".[2]

Oysters and shrimp are sensitive to severe weather conditions due to their requirements for water temperature and water salinity.[6] The changes in shrimp distribution have directly impacted the Vietnamese shrimping community.[7]

The EPA also notes that "rising temperatures may also harm fish by reducing levels of dissolved oxygen in the water, promoting harmful algal blooms, bacteria, and other factors that contribute to diseases in coastal waters".[2]

See also[edit]

- List of U.S. states and territories by carbon dioxide emissions

- Plug-in electric vehicles in Louisiana

References[edit]

- ^ Meyer, Robinson (June 29, 2017). "The American South Will Bear the Worst of Climate Change's Costs". The Atlantic.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "What Climate Change Means for Louisiana" (PDF). United States Environmental Protection Agency. August 2016.

- ^ a b McDonnell, Tim. "Louisiana's population is already moving to escape climate catastrophe". Quartz. Retrieved 2020-09-18.

- ^ Gibbens, Sarah (August 31, 2021). "How climate change is fueling hurricanes like Ida". National Geographic. Archived from the original on August 31, 2021. Retrieved September 1, 2021.

- ^ Nilsen, Ella (November 14, 2023). "No place in the US is safe from the climate crisis, but a new report shows where it's most severe". CNN.

- ^ Buchanan, Susan (18 February 2019). "Climate change hurts Louisiana's oysters and shrimp". Louisiana Weekly. Archived from the original on 2019-02-20. Retrieved 2019-11-13.

- ^ Wist, Allie (2019-11-13). "How Louisiana's Vietnamese Shrimpers Are Adapting to Climate Change". Saveur. Archived from the original on 2019-11-13. Retrieved 2019-11-13.

Further reading[edit]

- Carter, L.; A. Terando; K. Dow; K. Hiers; K.E. Kunkel; A. Lascurain; D. Marcy; M. Osland; P. Schramm (2018). "Southeast". In Reidmiller, D.R.; C.W. Avery; D.R. Easterling; K.E. Kunkel; K.L.M. Lewis; T.K. Maycock; B.C. Stewart (eds.). Impacts, Risks, and Adaptation in the United States: Fourth National Climate Assessment, Volume II (Report). Washington, DC, USA: U.S. Global Change Research Program. pp. 872–940. doi:10.7930/NCA4.2018.CH19.—this chapter of the National Climate Assessment covers Southeast states (Virginia, West Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Florida, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, Tennessee, Arkansas, Louisiana).