No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| (One intermediate revision by one other user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{History of Greece}} |

{{History of Greece}} |

||

The '''Minoan Civilization''' ([[Greek language|Greek]]:: Μίνως [http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/cgi-bin/ptext?layout.reflang=greek;layout.refembed=2;layout.refwordcount=1;layout.refdoc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01.0165;layout.reflookup=%2Ami%2Fnw;layout.refcit=book%3D1%3Asection%3D624a;doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.04.0057%3Aentry%3D%2367910;layout.refabo=Perseus%3Aabo%3Atlg%2C0059%2C034 ]) was a pre-[[Ancient Greece|Hellenic]] [[Bronze Age]] civilization which arose on [[Crete]], a [[Greece|Greek]] island in the [[Aegean Sea]]. The Minoan culture flourished from approximately 2700 to 1450 BC when it is superseded by the [[Mycenaean Greece|Mycenaean]] culture on the island. The Minoans were one of the [[Mediterranean]] civilizations that flourished during the Bronze Age. These civilizations had much contact with each other, sometimes making it difficult to judge the extent to which the Minoans influenced, or were influenced by, their neighbors. |

The '''Minoan Civilization''' ([[Greek language|Greek]]:: Μίνως [http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/cgi-bin/ptext?layout.reflang=greek;layout.refembed=2;layout.refwordcount=1;layout.refdoc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01.0165;layout.reflookup=%2Ami%2Fnw;layout.refcit=book%3D1%3Asection%3D624a;doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.04.0057%3Aentry%3D%2367910;layout.refabo=Perseus%3Aabo%3Atlg%2C0059%2C034 ]) was a pre-[[Ancient Greece|Hellenic]] [[Bronze Age]] civilization which arose on [[Crete]], a [[Greece|Greek]] island in the [[Aegean Sea]]. The Minoan culture flourished from approximately 2700 to 1450 BC when it is superseded by the [[Mycenaean Greece|Mycenaean]] culture on the island. The Minoans were one of the [[Mediterranean]] civilizations that flourished during the Bronze Age. These civilizations had much contact with each other, sometimes making it difficult to judge the extent to which the Minoans influenced, or were influenced by, their neighbors. |

||

Minoan [[Palace]]s are the best known [[building]] types to have been excavated on the island. They are [[monument]]al buildings serving [[administrative]] purposes as evidenced by the large [[archive]]s unearthed by [[archaeologist]]s. Each of the palaces excavated to date have their own unique features, but they also share features which set them apart from other structures. The palaces were often multi-storied with interior and exterior [[staircase]]s, light wells, massive [[column]]s, storage magazines and courtyards. |

Minoan [[Palace]]s are the best known [[building]] types to have been excavated on the island. They are [[monument]]al buildings serving [[administrative]] purposes as evidenced by the large [[archive]]s unearthed by [[archaeologist]]s. Each of the palaces excavated to date have their own unique features, but they also share features which set them apart from other structures. The palaces were often multi-storied with interior and exterior [[staircase]]s, light wells, massive [[column]]s, storage magazines and courtyards. |

||

The term "Minoan" was coined by the British archaeologist Sir [[Arthur Evans]] |

The term "Minoan" was coined by the British archaeologist Sir [[Arthur Evans]] after the mythic [[king]] [[Minos]].<ref>John Bennet, "Minoan civilization", ''[[Oxford Classical Dictionary]]'', 3rd ed., p. 985.</ref> Minos was associated in [[Greek_Mythology|myth]] with the [[labyrinth]], which Evans identified as the site at [[Knossos]]. It is not known whether "Minos" was a personal name or a title. What the Minoans called themselves is unknown, although the [[Ancient Egypt|Egyptian]] place name "Keftiu" (*''kaftāw'') and the [[Semitic]] "Kaftor" or "[[Caphtor]]" and "Kaptara" in the [[Mari]] archives apparently refers to the island of Crete. In the ''[[Odyssey]]'' which was composed after the destruction of the Minoan civilization, [[Homer]] calls the natives of Crete [[Eteocretan language|Eteocretans]] meaning, 'aboriginal Cretans'. In [http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/cgi-bin/ptext?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01.0165 Plato's Laws], the Athenian stranger of the dialogue asks from the Cretan if his Cretan legal system is derived from Minos and Cleinias the Cretan replies affirmatively.[http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/cgi-bin/ptext?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01.0165] |

||

==Chronology and history== |

==Chronology and history== |

||

| Line 302: | Line 303: | ||

* [http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/cgi-bin/ptext?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01.0165 Plato Laws [624a]] |

* [http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/cgi-bin/ptext?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01.0165 Plato Laws [624a]] |

||

* [http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/cgi-bin/ptext?layout.reflang=greek;layout.refembed=2;layout.refwordcount=1;layout.refdoc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01.0165;layout.reflookup=%2Ami%2Fnw;layout.refcit=book%3D1%3Asection%3D624a;doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.04.0057%3Aentry%3D%2367910;layout.refabo=Perseus%3Aabo%3Atlg%2C0059%2C034 Minôs by Liddell & Scott Greek Lexicon] |

* [http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/cgi-bin/ptext?layout.reflang=greek;layout.refembed=2;layout.refwordcount=1;layout.refdoc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01.0165;layout.reflookup=%2Ami%2Fnw;layout.refcit=book%3D1%3Asection%3D624a;doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.04.0057%3Aentry%3D%2367910;layout.refabo=Perseus%3Aabo%3Atlg%2C0059%2C034 Minôs by Liddell & Scott Greek Lexicon] |

||

[[Category:Aegean civilization]] |

|||

[[Category:Ancient Greece]] |

|||

[[Category:Minoan civilization|*]] |

|||

[[ar:حضارة مينوسية]] |

|||

[[bg:Минойска цивилизация]] |

|||

[[da:Minoisk kultur]] |

|||

[[de:Minoische Kultur]] |

|||

[[el:Μινωικός πολιτισμός]] |

|||

[[es:Civilización minoica]] |

|||

[[eo:Minoa civilizo]] |

|||

[[eu:Zibilizazio minoiko]] |

|||

[[fa:مینوسیها]] |

|||

[[fr:Civilisation minoenne]] |

|||

[[gl:Civilización minoica]] |

|||

[[is:Mínóísk menning]] |

|||

[[it:Civiltà minoica]] |

|||

[[he:התרבות המינואית]] |

|||

[[lt:Mino civilizacija]] |

|||

[[nl:Minoïsche beschaving]] |

|||

[[ja:クレタ文明]] |

|||

[[no:Minoisk kultur]] |

|||

[[nn:Den minoiske sivilisasjonen]] |

|||

[[pl:Kultura minojska]] |

|||

[[pt:Civilização minóica]] |

|||

[[ru:Минойская цивилизация]] |

|||

[[sr:Минојска цивилизација]] |

|||

[[fi:Minolainen kulttuuri]] |

|||

[[sv:Minoer]] |

|||

[[uk:Мінойська культура]] |

|||

[[zh:米诺斯文明]] |

|||

==Chronology and history== |

|||

{{details|Minoan chronology|Minoan chronology}} |

|||

{{details|Minoan pottery|Minoan pottery}} |

|||

Rather than give calendar dates for the Minoan period, archaeologists use two systems of [[chronology|relative chronology]]. The first, created by Evans and modified by later archaeologists, is based on [[pottery]] styles. It divides the Minoan period into three main eras—Early Minoan (EM), Middle Minoan (MM), and Late Minoan (LM). These eras are further subdivided, e.g. Early Minoan I, II, III (EMI, EMII, EMIII). Another dating system, proposed by the Greek archaeologist [[Nicolas Platon]], is based on the development of the architectural complexes known as "palaces" at [[Knossos]], [[Phaistos]], [[Malia]], and [[Kato Zakros]], and divides the Minoan period into Prepalatial, Protopalatial, Neopalatial, and Post-palatial periods. The relationship among these systems is given in the accompanying table, with approximate calendar dates drawn from Warren and Hankey (1989). |

|||

All calendar dates given in this article are approximate, and the subject of ongoing debate. |

|||

The [[Thera eruption]] occurred during a mature phase of the LM IA period. The calendar date of the volcanic eruption is extremely controversial; see the article on [[Thera eruption#Dating the volcanic eruption|Thera eruption]] for discussion. It often is identified as a catastrophic natural event for the culture, leading to its rapid collapse, perhaps being related mythically as [[Atlantis]] by Classical Greeks. |

|||

===History=== |

|||

{|align=right border="1" cellpadding="1" cellspacing="0" style="font-size: 95%; border: gray solid 1px; border-collapse: collapse; text-align: center;" |

|||

|- style="background: #ececec;" |

|||

! colspan="14" style="background: #f9f9f9; text-align: center;" | '''Minoan chronology''' |

|||

|- |

|||

| 3650-3000 BC |

|||

| EMI |

|||

| rowspan=4 valign="top" | '''Prepalatial''' |

|||

|- |

|||

| 2900-2300 BC |

|||

| |

|||

|- |

|||

| 2300-2160 BC |

|||

| EMIII |

|||

|- |

|||

| 2160-1900 BC |

|||

| MMIA |

|||

|- |

|||

| 1900-1800 BC |

|||

| MMIB |

|||

| rowspan=2 valign="top" | '''Protopalatial'''<br />(Old Palace Period) |

|||

|- |

|||

| 1800-1700 BC |

|||

| MMII |

|||

|- |

|||

| 1700-1640 BC |

|||

| MMIIIA |

|||

| rowspan=4 valign="top" | '''Neopalatial'''<br />(New Palace Period) |

|||

|- |

|||

| 1640-1600 BC |

|||

| MMIIIB |

|||

|- |

|||

| 1600-1480 BC |

|||

| LMIA |

|||

|- |

|||

| 1480-1425 BC |

|||

| LMIB |

|||

|- |

|||

| 1425-1390 BC |

|||

| LMII |

|||

| rowspan=5 valign="top" | '''Postpalatial'''<br /> (At Knossos, Final Palace Period) |

|||

|- |

|||

| 1390-1370 BC |

|||

| LMIIIA1 |

|||

|- |

|||

| 1370-1340 BC |

|||

| LMIIIA2 |

|||

|- |

|||

| 1340-1190 BC |

|||

| LMIIIB |

|||

|- |

|||

| 1190-1170 BC |

|||

| LMIIIC |

|||

|- |

|||

| 1100 BC || Subminoan |

|||

|} |

|||

The oldest signs of inhabitants on Crete are ceramic [[Neolithic]] remains that date to approximately 7000 BC. See [[History of Crete]] for details. |

|||

The beginning of its Bronze Age, around 2600 BC, was a period of great unrest in Crete, and also marks the beginning of Crete as an important center of [[civilization]]. |

|||

At the end of the MMII period (1700 BC) there was a large disturbance in Crete, probably an earthquake, or possibly an invasion from [[Anatolia]]. The Palaces at Knossos, Phaistos, Malia, and Kato Zakros were destroyed. But with the start of the Neopalatial period, population increased again, the palaces were rebuilt on a larger scale and new settlements were built all over the island. This period (the seventeenth and sixteenth centuries BC, MM III / Neopalatial) represents the apex of the Minoan civilization. The [[en]] occurred during LMIA (and LHI). |

|||

On the Greek mainland, LHIIB began during LMIB, showing independence from Minoan influence. At the end of the LMIB period, the Minoan palace culture failed catastrophically. All palaces were destroyed, and only Knossos was immediately restored - although other palaces sprang up later in LMIIIA (like [[Chania]]). |

|||

LMIB ware has been found in Egypt under the reigns of [[Hatshepsut]] and [[Tuthmosis III]]. Either the LMIB/LMII catastrophe occurred after this time, or else it was so bad that the Egyptians then had to import LHIIB instead. |

|||

A short time after the LMIB/LMII catastrophe, around 1420 BC, the island was conquered by the [[Mycenaean Greece|Mycenaeans]], who adapted the [[Linear A]] Minoan script to the needs of their own [[Mycenaean language]], a form of [[Ancient Greek|Greek]], which was written in [[Linear B]]. The first such archive anywhere is in the LMII-era "Room of the Chariot Tablets". Later Cretan archives date to LMIIIA (contemporary with LHIIIA) but no later than that. |

|||

During LMIIIA:1, [[Amenhotep III]] at Kom el-Hatan took note of ''k-f-t-w'' (Kaftor) as one of the "Secret Lands of the North of Asia". Also mentioned are Cretan cities such as ''i-'m-n-y-s3''/''i-m-ni-s3'' (Amnisos), ''b3-y-s3-?-y'' (Phaistos), ''k3-t-w-n3-y'' (Kydonia) and ''k3-in-yw-s'' (Knossos) and some [[toponym]]s reconstructed as belonging to the Cyclades or the Greek mainland. If the values of these Egyptian names are accurate, then this [[pharaoh]] did not privilege LMIII Knossos above the other states in the region. |

|||

After about a century of partial recovery, most Cretan cities and palaces went into decline in the thirteenth century BC (LHIIIB/LMIIIB). |

|||

Knossos remained an administrative center until 1200 BC; the last of the Minoan sites was the defensive mountain site of [[Karfi]] a refuge site which displays vestiges of Minoan civilization almost into the [[Iron Age]]. |

|||

==Geography== |

|||

[[Image:Map Minoan Crete-en.svg|thumb|right|350px|Map of Minoan Crete]] |

|||

Crete is a [[mountain]]ous [[island]] with natural [[harbor]]s. There are signs of earthquake damage at many Minoan sites and clear signs of both uplifting of land and submersion of coastal sites due to [[tectonic]] processes all along the coasts. |

|||

[[Homer]] recorded a tradition that Crete had ninety cities. The island was probably divided into at least five political units during the height of the Minoan period and at different stages in the Bronze Age into more or less. The north is thought to have been governed from Knossos, the south from [[Phaistos]], the central eastern part from [[Malia]], and the eastern tip from [[Kato Zakros]] and the west from [[Chania]]. Smaller palaces have been found in other places. |

|||

Some of the major Minoan archaeological sites are: |

|||

*Palaces |

|||

**[[Knossos]] - the largest Bronze Age archaeological site on Crete; was purchased for excavations by Evans on March 16, 1900. |

|||

**[[Phaistos]] - the second largest palatial building on the island, excavated by the Italian school shortly after Knossos |

|||

**[[Malia (city)|Malia]] - the subject of French excavations, a palatial centre which affords a very interesting look into the development of the palaces in the protopalatial period |

|||

**[[Kato Zakros]] - a palatial site excavated by Greek archaeologists in the far east of the island |

|||

**[[Galatas_Palace|Galatas]] - the most recently confirmed palatial site |

|||

*[[Agia Triada]] - an administrative centre close to Phaistos |

|||

*[[Gournia]] - a town site excavated in the first quarter of the 20th Century by the American School |

|||

*[[Pyrgos]] - an early minoan site on the south of the island |

|||

*[[Vasiliki]] - an early minoan site towards the east of the island which gives its name to a distinctive ceramic ware |

|||

*[[Fournou Korifi|Fournu Korfi]] - a site on the south of the island |

|||

*[[Pseira]] - island town with ritual sites |

|||

*[[Mount Juktas]] - the greatest of the Minoan peak sanctuaries by virtue of its association with the palace of Knossos |

|||

*[[Arkalochori]] - the findsite of the famous [[Arkalochori Axe]] |

|||

*[[Karfi]] - a refuge site from the late minoan period, one of the last of the Minoan sites |

|||

==Society and culture== |

|||

[[Image:Copper Ingot Crete.jpg|thumb|200px|Minoan copper ingot]] |

|||

The Minoans were primarily a [[mercantile]] people engaged in overseas trade. Their culture, from ca 1700 BC onward, shows a high degree of organization. |

|||

Many historians and archaeologists believe that the Minoans were involved in the Bronze Age's important [[tin]] trade: tin, alloyed with copper apparently from [[Cyprus]], was used to make [[bronze]]. The decline of Minoan civilization and the decline in use of bronze tools in favor of superior iron ones seem to be correlated. |

|||

The Minoan trade in [[saffron]], which originated in the Aegean basin as a natural chromosome mutation, has left fewer material remains: a fresco of saffron-gatherers at [[Santorini]] is well-known. This inherited trade pre-dated Minoan civilization: a sense of its rewards may be gained by comparing its value to [[frankincense]], or later, to [[black pepper|pepper]]. Archaeologists tend to emphasize the more durable items of trade: ceramics, copper, and tin, and dramatic luxury finds of [[gold]] and [[silver]]. |

|||

Objects of Minoan manufacture suggest there was a network of trade with mainland [[Greece]] (notably [[Mycenae]]), [[Cyprus]], [[Syria]], [[Anatolia]], [[Egypt]], [[Mesopotamia]], and westward as far as the coast of [[Spain]]. <!--Spanish Minoan site should be mentioned here--> |

|||

[[Image:Knossos fresco women.jpg|thumb|300px|Fresco showing three women]] Minoan men wore [[loincloth]]s and [[kilt]]s. Women wore [[robe]]s that were open to the [[navel]], leaving their breasts exposed, and had short sleeves and layered flounced [[skirt]]s. Women also had the option of wearing a strapless fitted [[bodice]], the first fitted garments known in history. The patterns on [[clothes]] emphasized [[symmetry|symmetrical]] geometric designs. |

|||

The statues of [[priest|priestesses]] in Minoan culture and frescoes showing men and women participating in the same sports such as [[bull-leaping]], lead some archaeologists to believe that men and women held equal social status. Inheritance is thought to have been matrilineal. Minoan religion was goddess worship and women are represented as those officiating at religious ceremonies. The frescos include many depictions of people, with the genders distinguished by colour: the men's skin is reddish-brown, the women's white. |

|||

===Language and writing=== |

|||

[[Image:Disque de Phaistos A.jpg|thumb|right|250px|Unknown syllabic signs on the [[Phaistos Disc]]]] |

|||

Knowledge of the spoken and written language of the Minoans is scant, due to the small number of records found. Sometimes the Minoan language is referred to as [[Eteocretan language|Eteocretan]], but this presents confusion between the language written in [[Linear A|Linear A scripts]] and the language written in a [[History of the Alphabet|Euboean]]- derived alphabet after the [[Greek Dark Ages]]. While the Eteocretan language is suspected to be a descendant of Minoan, there is not enough source material in either language to allow conclusions to be made. It also is unknown whether the language written in [[Cretan hieroglyphs]] is Minoan. As with Linear A, it is undeciphered and its phonetic values are unknown. |

|||

Approximately 3,000 tablets bearing writing have been discovered so far in Minoan contexts. The overwhelming majority are in the [[Linear B]] script, apparently being inventories of goods or resources. Others are inscriptions on religious objects associated with [[Cult (religion)|cult]]. Because most of these inscriptions are concise economic records rather than dedicatory inscriptions, the translation of Minoan remains a challenge. The hieroglyphs came into use from MMI and were in parallel use with the emerging Linear A from the eighteenth century BC (MM II) and disappeared at some point during the seventeenth century BC (MM III). |

|||

In the Mycenean period, Linear A was replaced by Linear B, recording a very archaic version of the [[Greek language]]. Linear B was successfully deciphered by [[Michael Ventris]] in the 1950s, but the earlier scripts remain a mystery. Unless [[Eteocretan]] truly is its descendant, it is perhaps during the [[Greek Dark Ages]], a time of economic and socio-political collapse, that the Minoan language became extinct. |

|||

===Art=== |

|||

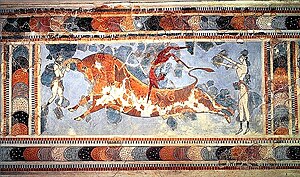

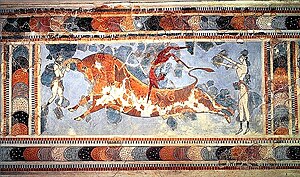

[[Image:Knossos bull.jpg|thumb|300px|right|A fresco found at the Minoan site of Knossos, indicating a sport or ritual of "bull leaping", the dark skinned figure is a man and the two light skinned figures are women]] |

|||

The great collection of Minoan art is in the museum at [[Heraklion]], near Knossos on the north shore of Crete. Minoan art, with other remains of [[material culture]], especially the sequence of ceramic styles, has allowed archaeologists to define the three phases of Minoan culture (EM, MM, LM) discussed above. |

|||

Since wood and textiles have vanished through decomposition, the most important surviving examples of Minoan art are [[Minoan pottery]], the palace architecture with its [[fresco]]s that include landscapes, [[stone carving]]s, and intricately carved [[Seal (device)|seal stones]]. |

|||

{{main|Minoan pottery}} |

|||

In the Early Minoan period ceramics were characterised by linear patterns of [[spiral]]s, [[triangle]]s, curved lines, [[cross]]es, [[fishbone]] motifs, and such. In the Middle Minoan period naturalistic designs such as [[fish]], [[squid]], [[bird]]s, and [[lily|lilies]] were common. In the Late Minoan period, flowers and animals were still the most characteristic, but the variability had increased. The 'palace style' of the region around Knossos is characterised by a strong [[geometric]] simplification of [[naturalism (art)|naturalistic]] shapes and [[monochrome|monochromatic]] paintings. Very noteworthy are the similarities between Late Minoan and [[Mycenaean Greece|Mycenaean]] art. |

|||

===Religion=== |

|||

<!-- Image with unknown copyright status removed: [[Image:Lk23m01f.jpg|thumb|200px|"Snake-Goddess" from Knossos]] --> |

|||

[[Image:Snake Goddess Crete 1600BC.jpg|thumb|200px|"[[Snake Goddess]]" or a priestess performing a ritual (MM III)]] |

|||

The Minoans worshiped goddesses.<ref>See Castleden 1994; Goodison and Morris 1998; N. Marinatos 1993; et al.</ref> Although there is some evidence of male gods, depictions of Minoan goddesses vastly outnumber depictions of anything that could be considered a Minoan god. While some of these depictions of women are believed to be images of worshipers and priestesses officiating at religious ceremonies, as opposed to the deity herself, there still seem to be several goddesses including a [[Mother Goddess]] of [[fertility rite|fertility]], a [[Mistress of the Animals]], a protectress of [[City|cities]], the [[Home|household]], the [[harvest]], and the [[underworld]], and more. Some have argued that these are all aspects of a single goddess. They are often represented by [[Serpent (symbolism)|serpents]], birds, poppies, and a somewhat vague shape of an animal upon the head. Some suggest the goddess was linked to the "Earthshaker", a male represented by the [[Cattle|bull]] and the [[sun]], who would die each [[autumn]] and be reborn each [[spring (season)|spring]]. Though the notorious bull-headed [[Minotaur]] is a purely Greek depiction, seals and seal-impressions reveal bird-headed or masked deities. |

|||

[[Walter Burkert]] warns: |

|||

:"To what extent one can and must differentiate between Minoan and Mycenaean religion is a question which has not yet found a conclusive answer"<ref>Burkert 1985, p. 21.</ref> |

|||

and suggests that useful parallels will be found in the relations between Etruscan and Archaic Greek culture and religion, or between Roman and Hellenistic culture. Minoan religion has not been transmitted in its own language, and the uses literate Greeks later made of surviving Cretan [[mytheme]]s, after centuries of purely oral transmission, have transformed the meager sources: consider the Athenian point-of-view of the [[Theseus]] legend. A few Cretan names are preserved in [[Greek mythology]], but there is no way to connect a name with an existing Minoan icon, such as the familiar [[Serpent (symbolism)|serpent]]-goddess. Retrieval of metal and clay votive figures— [[labrys|double axes]], miniature vessels, models of artifacts, animals, human figures—has identified sites of cult: here were numerous small shrines in Minoan Crete, and mountain peaks and very numerous sacred caves—over 300 have been explored—were the centers for some [[cult (religion)|cult]], but [[temple]]s as the Greeks developed them were unknown.<ref>Kerenyi 1976, p. 18; Burkert 1985, p. 24ff.</ref> Within the palace complex, no central rooms devoted to cult have been recognized, other than the center court where youths of both sexes would practice the [[bull-leaping]] ritual. It is notable that there are no Minoan frescoes that depict any deities. |

|||

Minoan sacred symbols include the [[Bull (mythology)|bull]] and its horns of consecration, the [[labrys]] (double-headed axe), the [[column|pillar]], the serpent, the sun-disk, and the [[tree]]. |

|||

===Warfare and "The Minoan Peace"=== |

|||

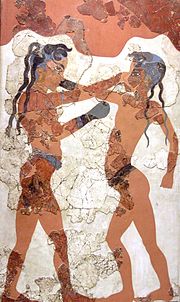

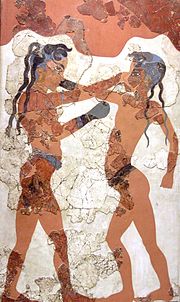

[[Image:NAMA Akrotiri 2.jpg|thumb|180px|Children [[boxing]] in a fresco on the island of [[Santorini]] ]] |

|||

Though the vision created by [[Sir Arthur Evans]] of a ''pax Minoica'', a "Minoan peace", has been criticised in recent years,<ref>Alexiou wrote of fortifications and acropolises in Minoan Crete, in ''Kretologia'' '''8''' (1979), pp 41-56, and especially in C.G. Starr, "Minoan flower-lovers" in ''The Minoan Thalassocracy: Myth and Reality'' R. Hägg and N. Marinatos, eds. (Stockholm) 1994, pp 9-12.</ref> it is generally assumed there was little internal armed conflict in Minoan Crete itself, until the following Mycenaean period.<ref>W.-B. Niemeier, "Mycenaean Knossos and the Age of Linear B", ''Studi micenei ed egeoanatolici'' 1982:275.</ref> As with much of Minoan Crete, however, it is hard to draw any obvious conclusions from the evidence. However, new excavations keep sustaining interests and documenting the impact around the Aegean [http://www.ekathimerini.com/4dcgi/_w_articles_ell_3096803_24/01/2007_79258] |

|||

Many argue that there is little evidence for ancient Minoan fortifications. But as S. Alexiou has pointed out (in ''Kretologia'' 8), a number of sites, especially Early and Middle Minoan sites such as Aghia Photia, are built on hilltops or are otherwise fortified. As Lucia Nixon said, "...we may have been over-influenced by the lack of what we might think of as solid fortifications to assess the archaeological evidence properly. As in so many other instances, we may not have been looking for evidence in the right places, and therefore we may not end with a correct assessment of the Minoans and their ability to avoid war."<ref>Nixon, “Changing Views of Minoan Society,” in ''Minoan Society'' ed L. Nixon.</ref>. |

|||

Chester Starr points out in "Minoan Flower Lovers" (Hagg-Marinatos eds. Minoan Thalassocracy) that [[Shang dynasty|Shang China]] and the [[Maya civilization|Maya]] both had unfortified centers and yet still engaged in frontier struggles, so that itself cannot be enough to definitively show the Minoans were a peaceful civilization unparalleled in history. |

|||

In 1998, however, when Minoan archaeologists met in a conference in Belgium to discuss the possibility that the idea of Pax Minoica was outdated, the evidence for Minoan war proved to be scanty. |

|||

Archaeologist Jan Driessen, for example, said the Minoans frequently show ‘weapons’ in their art, but only in ritual contexts, and that “The construction of fortified sites is often assumed to reflect a threat of warfare, but such fortified centers were multifunctional; they were also often the embodiment or material expression of the central places of the territories at the same time as being monuments glorifying and merging leading power” (Driessen 1999, p. 16). |

|||

On the other hand, Stella Chryssoulaki's work on the small outposts or 'guard-houses' in the east of the island represent possible elements of a defensive system. Claims that they produced no weapons are erroneous; type A Minoan swords (as found in palaces of Mallia and Zarkos) were the finest in all of the Aegean (See Sanders, AJA 65, 67, Hoeckmann, JRGZM 27, or Rehak and Younger, AJA 102). |

|||

Regarding Minoan weapons, however, archaeologist Keith Branigan notes that 95% of so-called Minoan weapons possessed hafting (hilts, handles) that would have prevented their use as weapons (Branigan, 1999). However more recent experimental testing of accurate replicas has shown this to be incorrect as these weapons were capable of cutting flesh down to the bone (and scoring the bone's surface) without any damage to the weapons themselves. Archaeologist Paul Rehak maintains that Minoan figure-eight shields could not have been used for fighting or even hunting, since they were too cumbersome (Rehak, 1999). And archaeologist Jan Driessen says the Minoans frequently show ‘weapons’ in their art, but only in ritual contexts (Driessen 1999). Finally, archaeologist Cheryl Floyd concludes that Minoan “weapons” were merely tools used for mundane tasks such as meat-processing (Floyd, 1999). Although this interpretation must remain highly questionable as there are no parallels of one-meter-long swords and large spearheads being used as culinary devices in the historic or ethnographic record. |

|||

About Minoan warfare in general, Branigan concludes that “[[T]]he quantity of weaponry, the impressive fortifications, and the aggressive looking long-boats all suggested an era of intensified hostilities. But on closer inspection there are grounds for thinking that all three key elements are bound up as much with status statements, display, and fashion as with aggression…. Warfare such as there was in the southern Aegean EBA [[early Bronze Age]] was either personalized and perhaps ritualized (in Crete) or small-scale, intermittent and essentially an economic activity (in the Cyclades and the Argolid/Attica) ” (1999, p. 92). Archaeologist Krzyszkowska concurs: “The stark fact is that for the prehistoric Aegean we have no [[sic]] direct evidence for war and warfare per se [[sic]]” (Krzyszkowska, 1999). |

|||

Furthermore, no evidence exists for a Minoan army, or for Minoan domination of peoples outside Crete. Few signs of warfare appear in Minoan art. “Although a few archaeologists see war scenes in a few pieces of Minoan art, others interpret even these scenes as festivals, sacred dance, or sports events” (Studebaker, 2004, p. 27). Although armed warriors are depicted being stabbed in the throat with swords, violence may occur in the context of ritual or blood sport. |

|||

Although on the Mainland of Greece at the time of the Shaft Graves at Mycenae, there is little evidence for major fortifications among the Mycenaeans there (the famous citadels post-date the destruction of almost all Neopalatial Cretan sites), the constant warmongering of other contemporaries of the ancient Minoans – the Egyptians and Hittites, for example – is well documented. |

|||

====Possibility of human sacrifice==== |

|||

[[Image:Labrys.jpg|thumb|200px|Minoan symbolic [[labrys]] of [[gold]], [[2nd millennium BC]]: many have been found in the [[Arkalochori]] cave.]] |

|||

Evidence that suggest the Minoans may have performed human sacrifice has been found at three sites: (1) [[Anemospilia]], in a MMII building near Mt. Juktas, interpreted as a temple, (2) an EMII sanctuary complex at [[Fournou Korifi]] in south central Crete, and (3) [[Knossos]], in an LMIB building known as the "North House." |

|||

The temple at Anemospilia was destroyed by earthquake in the MMII period. The building seems to be a tripartite shrine, and terracotta feet and some carbonized wood were interpreted by the excavators as the remains of a cult statue. Four human skeletons were found in its ruins; one, belonging to a young man, was found in an unusually contracted position on a raised platform, suggesting that he had been trussed up for sacrifice, much like the bull in the sacrifice scene on the Mycenaean-era [[Agia Triadha]] sarcophagus. A bronze dagger was among his bones, and the discoloration of the bones on one side of his body suggests he died of blood loss. The bronze blade was fifteen inches long and had images of a boar on each side. The bones were on a raised platform at the center of the middle room, next to a pillar with a trough at its base. |

|||

The positions of the other three skeletons suggest that an earthquake caught them by surprise—the skeleton of a twenty-eight year old woman was spread-eagled on the ground in the same room as the sacrificed male. Next to the sacrificial platform was the skeleton of a man in his late thirties, with broken legs. His arms were raised, as if to protect himself from falling debris, which suggests that his legs were broken by the collapse of the building in the earthquake. In the front hall of the building was the fourth skeleton, too poorly preserved to allow determination of age or gender. Nearby 105 fragments of a clay vase were discovered, scattered in a pattern that suggests it had been dropped by the person in the front hall when s/he was struck by debris from the collapsing building. The jar had apparently contained bull's blood. |

|||

Unfortunately, the excavators of this site have not published an official excavation report; the site is mainly known through a 1981 article in ''National Geographic'' (Sakellarakis and Sapouna-Sakellerakis 1981, see also Rutter<ref>[http://projectsx.dartmouth.edu/classics/history/bronze_age/lessons/les/15.html Lesson 15] of [http://projectsx.dartmouth.edu/classics/history/bronze_age/index.html The Prehistoric Archaeology of the Aegean] |

|||

accessed [[March 17]] 2006</ref>). |

|||

Not all agree that this was human sacrifice. Nanno Marinatos says the man supposedly sacrificed actually died in the earthquake that hit at the time he died. She notes that this earthquake destroyed the building, and also killed the two Minoans who supposedly sacrificed him. She also argues that the building was not a temple and that the evidence for sacrifice “is far from … conclusive."<ref>Marinatos 1993, p. 114.</ref> Dennis Hughes concurs and also argues that the platform where the man lay was not necessarily an altar, and the blade was probably a spearhead that may not have been placed on the young man, but could have fallen during the earthquake from shelves or an upper floor.<ref>Hughes 1991, p. ?{{Fact|date=February 2007}}</ref> |

|||

At the sanctuary-complex of Fournou Korifi, fragments of a human skull were found in the same room as a small hearth, cooking-hole, and cooking-equipment. This skull has been interpreted as the remains of a sacrificed victim.<ref>Gessell 1983.</ref> |

|||

In the "North House" at Knossos, the bones of at least four children (who had been in good health) were found which bore signs that "they were butchered in the same way the Minoans slaughtered their sheep and goats, suggesting that they had been sacrificed and eaten. The senior Cretan archaeologist Nicolas Platon was so horrified at this suggestion that he insisted the bones must be those of apes, not humans."<ref>MacGillivray 2000, ''Minotaur: Sir Arthur Evans and the Archaeology of the Minoan Myth"'' p.371</ref> |

|||

The bones, found by Peter Warren, date to Late Minoan IB (1580-1490), before the Myceneans arrived (in LM IIIA, circa 1320-1200) according to [[Paul Rehak]] and John G. Younger.<ref>"Review of Aegean Prehistory VII: Neopalatial, Final Palatial, and Postpalatial Crete," ''American Journal of Archaeology'' 102 (1998), pp. 91-173.</ref> Dennis Hughes and Rodney Castleden argue that these bones were deposited as a 'secondary burial'.<ref>Hughes 1991; Castleden 1991</ref> Secondary burial is the not-uncommon practice of burying the dead twice: immediately following death, and then again after the flesh is gone from the skeleton. The main weakness of this argument is that it does not explain the type of cuts and knife marks upon the bones. |

|||

==Architecture== |

|||

The Minoan cities were connected with stone-paved [[road]]s, formed from blocks cut with bronze [[saw]]s. Streets were drained and water and [[sewer]] facilities were available to the upper class, through [[clay]] pipes. |

|||

Minoan buildings often had flat tiled roofs; [[plaster]], wood, or [[flagstone]] [[floor]]s, and stood two to three stories high. Typically the lower [[wall]]s were constructed of stone and [[rubble]], and the upper walls of [[mudbrick]]. Ceiling timbers held up the roofs. |

|||

===Palaces=== |

|||

[[Image:Palace of Knossus.jpg|thumb|left|250px|Ruins of the palace at Knossos]] |

|||

The first palaces were constructed at the end of the Early Minoan period in the third millennium BC ([[Malia]]). While it was formerly believed that the foundation of the first palaces was synchronous and dated to the Middle Minoan at around 2000 BC (the date of the first palace at Knossos), scholars now think that palaces were built over a longer period of time in different locations, in response to local developments. The main older palaces are Knossos, Malia, and Phaistos. |

|||

The palaces fulfilled a plethora of functions: they served as centres of [[government]], administrative offices, [[shrine]]s, workshops, and storage spaces (e.g., for grain). These distinctions might have seemed artificial to Minoans. |

|||

The use of the term 'palace' for the older palaces, meaning a dynastic residence and seat of power, has recently come under criticism (see [[Palace]]), and the term 'court building' has been proposed instead. However, the original term is probably too well entrenched to be replaced. Architectural features such as [[ashlar]] masonry, [[orthostat]]s, columns, open courts, staircases (implying upper stories), and the presence of diverse basins have been used to define palatial architecture. |

|||

Often the conventions of better-known, younger palaces have been used to reconstruct older ones, but this practice may be obscuring fundamental functional differences. Most older palaces had only one story and no representative facades. They were U-shaped, with a big central court, and generally were smaller than later palaces. Late palaces are characterised by multi-storey buildings. The west facades had sandstone ashlar masonry. Knossos is the best-known example. See [[Knossos]]. |

|||

[[Image:Knossos frise pieuvre edit.jpg|thumb|300px|Fresco from the "Palace of Minos", [[Knossos]], Crete]] |

|||

[[Image:Knossos Poterie 2.JPG|thumb|right|300px|Storage jars in Knossos]] |

|||

===Columns=== |

|||

One of the most notable contributions of Minoans to architecture is their unique column, which was wider at the top than the bottom. It is called an 'inverted' column because most Greek columns are wider at the bottom, creating an illusion of greater height. The columns were also made of wood as opposed to stone, and were generally painted red. They were mounted on a simple stone base and were topped with a pillow-like, round piece as a capital.<ref>Benton and DiYanni 1998, p. 67.</ref><ref>Bourbon 1998, p 34</ref> |

|||

==Agriculture== |

|||

The Minoans raised [[cow|cattle]], [[sheep]], [[pig]]s, and [[goat]]s, and grew [[wheat]], [[barley]], [[vetch]], and [[chickpea]]s, they also cultivated [[grape]]s, [[fig]]s, and [[olive]]s, and grew [[poppy|poppies]], for poppyseed and perhaps, opium. The Minoans domesticated [[bee]]s, and adopted [[pomegranate]]s and [[quince]]s from the Near East, although not [[lemon]]s and [[orange (fruit)|oranges]] as is often imagined. They developed Mediterranean polyculture, the practice of growing more than one crop at a time, and as a result of their more varied and healthy diet, the population increased. |

|||

Farmers used wooden [[plow]]s, bound by leather to wooden handles, and pulled by pairs of [[donkey]]s or [[ox|oxen]]. |

|||

==Theories of Minoan demise== |

|||

===Thera eruption=== |

|||

{{main|Thera eruption}} |

|||

[[Thera]] is the largest island of [[Santorini]], a collapsed [[caldera]] about 100 km distant from Crete. The [[Thera eruption]] (estimated to have had a [[Volcanic Explosivity Index]] of 6) has been identified by ash fallout in eastern Crete, and in cores from the Aegean and Eastern Mediterranean seafloors. The cataclysmic eruption of Thera led to the volcano's collapse into a submarine [[caldera]], causing [[tsunami]]s which may have damaged naval installations and settlements near the coasts. The level of impact of the Thera eruption on the Minoan civilization is debated. |

|||

* Claims were made{{who}} that the ash falling on the eastern half of Crete may have choked off plant life, causing starvation. It was alleged that 7-11 cm of ash fell on Kato Zakro, while 0.5 cm fell on Knossos. However, when field examinations were carried out, this theory was dropped, as no more than 5 mm had fallen anywhere in Crete. (Callender, 1999) Earlier historians and archaeologists appear to have been deceived by the depth of pumice found on the sea floor. It has now been established that the pumice oozed from a lateral crack in the volcano below sea level (Pichler & Friedrich, 1980). |

|||

* The calendar date of the eruption is much disputed, but with [[radiocarbon dating]] has settled about 1630 BCE; archaeological popularizers who wish to synchronize the eruption with [[Conventional Egyptian chronology]] prefer a date around 1550 BCE. |

|||

* Archaeological research by a [[NOAA]] team of international scientists in 2006 have revealed that the Santorini event was much larger than the estimated 39 cubic km of [[Dense-Rock Equivalent]] (DRE), or total material erupted from the volcano, published in 1991; the expedition also mapped the caldera of the [[Kolumbo underwater volcano]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.uri.edu/news/releases/?id=3654|title=Santorini eruption much larger than originally believed|date=2006|accessdate=2007-03-10}}</ref>. The volume of [[ejecta]] was up to four times what was thrown into the stratosphere by [[Krakatau]] in 1883, a well-recorded event, placing the [[VEI|Volcanic Explosivity Index]] of the Thera eruption at approximately 6. <ref name="Oppenheimer2003">{{cite journal|last=Oppenheimer|first=Clive|title=Climatic, environmental and human consequences of the largest known historic eruption: Tambora volcano (Indonesia) 1815|journal=Progress in Physical Geography|volume=27|issue=2|date=2003|pages=230-259|url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1191/0309133303pp379ra}}</ref> |

|||

==Notes== |

|||

<!--This article uses the Cite.php citation mechanism. If you would like more information on how to add references to this article, please see http://meta.wikimedia.org/wiki/Cite/Cite.php --> |

|||

<div class="references-small" style="-moz-column-count:2; column-count:2;"> |

|||

<references /> |

|||

</div> |

|||

==References== |

|||

*Benton, Janetta Rebold and DiYanni, Robert. ''Arts and Culture: An Introduction to the Humanities.'' Volume 1. Prentice Hall. New Jersey, 1998. |

|||

*Bourbon, F. ''Lost Civilizations''. Barnes and Noble, Inc. New York, 1998. |

|||

*Branigan, Keith, 1970. ''The Foundations of Palatial Crete''. |

|||

*Branigan, Keith, 1999. "The Nature of Warfare in the Southern Aegean During the Third Millennium B.C.,” pp. 87-94 In Laffineur, Robert, ed., ''Polemos: Le Contexte Guerrier en Egee a L’Age du Bronze. Actes de la 7e Rencontre egeenne internationale Universite de Liege, 1998.'' Universite de Liege, Histoire de l’art d’archeologie de la Grece antique. |

|||

*Burkert, Walter, 1985. ''Greek Religion''. J. Raffan, trans. Cambridge: Harvard Univ. Press. ISBN 0-674-36281-0 |

|||

*Cadogan, Gerald, 1992, “ Ancient and Modern Crete,” in Myers et al., 1992, ''Aerial Atlas of Ancient Crete''. |

|||

*{{cite book | first=Rodney | last=Castleden | authorlink= | coauthors= | year=1993 | title=Minoans: Life in Bronze Age Crete | edition= | publisher=Routledge | location= | id=041508833X }} |

|||

*Callender, Gae (1999) ''The Minoans and the Mycenaeans: Aegean Society in the Bronze Age'' Oxford university press, Victoria 3205, Australia |

|||

*Driessen, Jan, 1999."The Archaeology of Aegean Warfare,” pp. 11-20 in Laffineur, Robert, ed., ''Polemos: Le Contexte Guerrier en Egee a L’Age du Bronze. Actes de la 7e Rencontre egeenne internationale Universite de Liege, 1998.'' Universite de Liege, Histoire de l’art d’archeologie de la Grece antique. |

|||

*[[Arthur Evans|Sir Arthur Evans]], 1921-35. ''The Palace of Minos: A Comparative Account of the Successive Stages of the Early Cretan Civilization as Illustrated by the Discoveries at Knossos'', 4 vols. in 6 (reissued 1964). |

|||

*Floyd, Cheryl, 1999. “Observations on a Minoan Dagger from Chrysokamino,” pp. 433-442 In Laffineur, Robert, ed., ''Polemos: Le Contexte Guerrier en Egee a L’Age du Bronze. Actes de la 7e Rencontre egeenne internationale Universite de Liege, 1998.'' Universite de Liege, Histoire de l’art d’archeologie de la Grece antique. |

|||

*Gates, Charles, 1999. “Why Are There No Scenes of Warfare in Minoan Art?” pp 277-284 In Laffineur, Robert, ed., ''Polemos: Le Contexte Guerrier en Egee a L’Age du Bronze. Actes de la 7e Rencontre egeenne internationale Universite de Liege, 1998.'' Universite de Liege, Histoire de l’art d’archeologie de la Grece antique. |

|||

*Hägg, R. and N. Marinatos, eds. ''The Minoan Thalassocracy: Myth and Reality'' (Stockholm) 1994. A summary of revived points-of-view of a Minoan thalassocracy, especially in LMI.. |

|||

*{{Harvard reference | Surname=Gesell | Given=G.C. | Year= 1983 | Chapter=The Place of the Goddess in Minoan Society | Editor=O. Krzyszkowska and L. Nixon | Title=Minoan Society | Edition= | Publisher= | Place=Bristol | URL= | Access-date= }} |

|||

*Goodison, Lucy, and Christine Morris, 1998, “Beyond the Great Mother: The Sacred World of the Minoans,” in Goodison, Lucy, and Christine Morris, eds., ''Ancient Goddesses: The Myths and the Evidence'', London: British Museum Press, pp. 113-132. |

|||

*Hawkes, Jacquetta, 1968. ''Dawn of the Gods.'' New York: Random House. ISBN 0-7011-1332-4 |

|||

*Higgins, Reynold, 1981. ''Minoan and Mycenaean Art'', (revised edition). |

|||

*Hood, Sinclair, 1971, ''The Minoans: Crete in the Bronze Age''. London. |

|||

*Hood, Sinclair, 1971. ''The Minoans: The Story of Bronze Age Crete'' |

|||

*Hutchinson, Richard W., 1962. ''Prehistoric Crete'' (reprinted 1968) |

|||

*Krzszkowska, Olga, 1999. “So Where’s the Loot? The Spoils of War and the Archaeological Record,” pp. 489-498 In Laffineur, Robert, ed., ''Polemos: Le Contexte Guerrier en Egee a L’Age du Bronze.'' ''Actes de la 7e Rencontre egeenne internationale Universite de Liege, 1998.'' Université de Liege, Histoire de l’art d’archeologie de la Grece antique. |

|||

*Lapatin, Kenneth, 2002. ''Mysteries of the Snake Goddess: Art, Desire, and the Forging of History''. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-306-81328-9 |

|||

*Manning, S.W., 1995. "An approximate Minoan Bronze Age chronology" in A.B. Knapp, ed., ''The absolute chronology of the Aegean Early Bronze Age: Archaeology, radiocarbon and history'' (Appendix 8), in series ''Monographs in Mediterranean Archaeology'', Vol. 1 (Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press) A standard current Minoan chronology. |

|||

*Marinatos, Nanno, 1993. ''Minoan Religion: Ritual, Image, and Symbol''. Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press. |

|||

*[[Spyridon Marinatos|Marinatos, Spyridon]], 1960. ''Crete and Mycenae'' (originally published in Greek, 1959), photographs by Max Hirmer. |

|||

*[[Spyridon Marinatos|Marinatos, Spyridon]], 1972. "Life and Art in Prehistoric Thera," in ''Proceedings of the British Academy'', vol 57. |

|||

*Mellersh, H.E.L., 1967. ''Minoan Crete.'' New York, G.P. Putnam’s Sons. |

|||

*Nixon, L., 1983. “Changing Views of Minoan Society," in L. Nixon, ed. ''Minoan society: Proceedings of the Cambridge Colloquium, 1981.'' |

|||

*Quigley, Carroll, 1961. ''The Evolution of Civilizations: An Introduction to Historical Analysis,'' Indianapolis: Liberty Press. |

|||

* Papadopoulos, John K., "Inventing the Minoans: Archaeology, Modernity and the Quest for European Identity", ''Journal of Mediterranean Archaeology'' '''18''':1:87-149 (June 2005) |

|||

* Pichler, H & Friedrich, W, L (1980) ''Mechanism of the Minoan Eruption of Santorini'', in ''Thera and the Aegean World'', vol.2, ed. C. Doumas, London |

|||

*Rehak, Paul, 1999. “The Mycenaean ‘Warrior Goddess’ Revisited,” pp. 227-240, in Laffineur, Robert, ed. ''Polemos: Le Contexte Guerrier en Egee a L’Age du Bronze. Actes de la 7e Rencontre egeenne internationale Universite de Liege, 1998. Universite de Liege, Histoire de l’art d’archeologie de la Grece antique.'' |

|||

*Schoep, Ilse, 2004. "Assessing the role of architecture in conspicuous consumption in the Middle Minoan I-II Periods." ''Oxford Journal of Archaeology'' vol 23/3, pp. 243-269. |

|||

*{{cite journal | author= Sakellarakis, Y. and E. Sapouna-Sakellarakis| title= Drama of Death in a Minoan Temple | journal=National Geographic | year=1981 | volume=159 | issue=2 | pages= 205–222 | url= }} |

|||

*Warren P., Hankey V., 1989. ''Aegean Bronze Age Chronology'' (Bristol). |

|||

*Willetts, R. F., 1976 [[1995 edition]]. ''The Civilization of Ancient Crete''. New York: Barnes & Noble Books. ISBN 1-84212-746-2 |

|||

==See also== |

|||

{{commonscat|Minoan civilization}} |

|||

* [[Linear A]] |

|||

* [[Peak sanctuaries]] |

|||

* [[Sacred caves]] |

|||

* [[Philistines]] |

|||

* [[Atlantis#Crete and Santorini|Atlantis]] |

|||

* [[Phaistos Disc]] |

|||

* [[Hyksos]] |

|||

== External links == |

|||

* [http://www.therafoundation.org/ Thera Foundation] |

|||

* [http://au.encarta.msn.com/encyclopedia_761564658/Minoan_Civilization.html Minoan Civilization] (Encarta) |

|||

* Donald A. MacKenzie, ''[http://www.sacred-texts.com/cla/moc/index.htm MYTHS OF CRETE & PRE-HELLENIC EUROPE]'', 1917, etext at sacred-texts.com. This is a very thorough text, but given its age and so on, much of its analysis and many of its statements need to be taken with a grain of salt. |

|||

* [http://www.matala-holidays.gr/knossos.php The Palace of Minoan Civilization] |

|||

[[Category:Aegean civilization]] |

[[Category:Aegean civilization]] |

||

Revision as of 22:26, 16 June 2007

| History of Greece |

|---|

|

|

|

The Minoan Civilization (Greek:: Μίνως [1]) was a pre-Hellenic Bronze Age civilization which arose on Crete, a Greek island in the Aegean Sea. The Minoan culture flourished from approximately 2700 to 1450 BC when it is superseded by the Mycenaean culture on the island. The Minoans were one of the Mediterranean civilizations that flourished during the Bronze Age. These civilizations had much contact with each other, sometimes making it difficult to judge the extent to which the Minoans influenced, or were influenced by, their neighbors.

Minoan Palaces are the best known building types to have been excavated on the island. They are monumental buildings serving administrative purposes as evidenced by the large archives unearthed by archaeologists. Each of the palaces excavated to date have their own unique features, but they also share features which set them apart from other structures. The palaces were often multi-storied with interior and exterior staircases, light wells, massive columns, storage magazines and courtyards.

The term "Minoan" was coined by the British archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans after the mythic king Minos.[1] Minos was associated in myth with the labyrinth, which Evans identified as the site at Knossos. It is not known whether "Minos" was a personal name or a title. What the Minoans called themselves is unknown, although the Egyptian place name "Keftiu" (*kaftāw) and the Semitic "Kaftor" or "Caphtor" and "Kaptara" in the Mari archives apparently refers to the island of Crete. In the Odyssey which was composed after the destruction of the Minoan civilization, Homer calls the natives of Crete Eteocretans meaning, 'aboriginal Cretans'. In Plato's Laws, the Athenian stranger of the dialogue asks from the Cretan if his Cretan legal system is derived from Minos and Cleinias the Cretan replies affirmatively.[2]

Chronology and history

Rather than give calendar dates for the Minoan period, archaeologists use two systems of relative chronology. The first, created by Evans and modified by later archaeologists, is based on pottery styles. It divides the Minoan period into three main eras—Early Minoan (EM), Middle Minoan (MM), and Late Minoan (LM). These eras are further subdivided, e.g. Early Minoan I, II, III (EMI, EMII, EMIII). Another dating system, proposed by the Greek archaeologist Nicolas Platon, is based on the development of the architectural complexes known as "palaces" at Knossos, Phaistos, Malia, and Kato Zakros, and divides the Minoan period into Prepalatial, Protopalatial, Neopalatial, and Post-palatial periods. The relationship among these systems is given in the accompanying table, with approximate calendar dates drawn from Warren and Hankey (1989).

All calendar dates given in this article are approximate, and the subject of ongoing debate.

The Thera eruption occurred during a mature phase of the LM IA period. The calendar date of the volcanic eruption is extremely controversial; see the article on Thera eruption for discussion. It often is identified as a catastrophic natural event for the culture, leading to its rapid collapse, perhaps being related mythically as Atlantis by Classical Greeks.

History

| Minoan chronology | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3650-3000 BC | EMI | Prepalatial | |||||||||||

| 2900-2300 BC | |||||||||||||

| 2300-2160 BC | EMIII | ||||||||||||

| 2160-1900 BC | MMIA | ||||||||||||

| 1900-1800 BC | MMIB | Protopalatial (Old Palace Period) | |||||||||||

| 1800-1700 BC | MMII | ||||||||||||

| 1700-1640 BC | MMIIIA | Neopalatial (New Palace Period) | |||||||||||

| 1640-1600 BC | MMIIIB | ||||||||||||

| 1600-1480 BC | LMIA | ||||||||||||

| 1480-1425 BC | LMIB | ||||||||||||

| 1425-1390 BC | LMII | Postpalatial (At Knossos, Final Palace Period) | |||||||||||

| 1390-1370 BC | LMIIIA1 | ||||||||||||

| 1370-1340 BC | LMIIIA2 | ||||||||||||

| 1340-1190 BC | LMIIIB | ||||||||||||

| 1190-1170 BC | LMIIIC | ||||||||||||

| 1100 BC | Subminoan | ||||||||||||

The oldest signs of inhabitants on Crete are ceramic Neolithic remains that date to approximately 7000 BC. See History of Crete for details.

The beginning of its Bronze Age, around 2600 BC, was a period of great unrest in Crete, and also marks the beginning of Crete as an important center of civilization.

At the end of the MMII period (1700 BC) there was a large disturbance in Crete, probably an earthquake, or possibly an invasion from Anatolia. The Palaces at Knossos, Phaistos, Malia, and Kato Zakros were destroyed. But with the start of the Neopalatial period, population increased again, the palaces were rebuilt on a larger scale and new settlements were built all over the island. This period (the seventeenth and sixteenth centuries BC, MM III / Neopalatial) represents the apex of the Minoan civilization. The en occurred during LMIA (and LHI).

On the Greek mainland, LHIIB began during LMIB, showing independence from Minoan influence. At the end of the LMIB period, the Minoan palace culture failed catastrophically. All palaces were destroyed, and only Knossos was immediately restored - although other palaces sprang up later in LMIIIA (like Chania).

LMIB ware has been found in Egypt under the reigns of Hatshepsut and Tuthmosis III. Either the LMIB/LMII catastrophe occurred after this time, or else it was so bad that the Egyptians then had to import LHIIB instead.

A short time after the LMIB/LMII catastrophe, around 1420 BC, the island was conquered by the Mycenaeans, who adapted the Linear A Minoan script to the needs of their own Mycenaean language, a form of Greek, which was written in Linear B. The first such archive anywhere is in the LMII-era "Room of the Chariot Tablets". Later Cretan archives date to LMIIIA (contemporary with LHIIIA) but no later than that.

During LMIIIA:1, Amenhotep III at Kom el-Hatan took note of k-f-t-w (Kaftor) as one of the "Secret Lands of the North of Asia". Also mentioned are Cretan cities such as i-'m-n-y-s3/i-m-ni-s3 (Amnisos), b3-y-s3-?-y (Phaistos), k3-t-w-n3-y (Kydonia) and k3-in-yw-s (Knossos) and some toponyms reconstructed as belonging to the Cyclades or the Greek mainland. If the values of these Egyptian names are accurate, then this pharaoh did not privilege LMIII Knossos above the other states in the region.

After about a century of partial recovery, most Cretan cities and palaces went into decline in the thirteenth century BC (LHIIIB/LMIIIB).

Knossos remained an administrative center until 1200 BC; the last of the Minoan sites was the defensive mountain site of Karfi a refuge site which displays vestiges of Minoan civilization almost into the Iron Age.

Geography

Crete is a mountainous island with natural harbors. There are signs of earthquake damage at many Minoan sites and clear signs of both uplifting of land and submersion of coastal sites due to tectonic processes all along the coasts.

Homer recorded a tradition that Crete had ninety cities. The island was probably divided into at least five political units during the height of the Minoan period and at different stages in the Bronze Age into more or less. The north is thought to have been governed from Knossos, the south from Phaistos, the central eastern part from Malia, and the eastern tip from Kato Zakros and the west from Chania. Smaller palaces have been found in other places.

Some of the major Minoan archaeological sites are:

- Palaces

- Knossos - the largest Bronze Age archaeological site on Crete; was purchased for excavations by Evans on March 16, 1900.

- Phaistos - the second largest palatial building on the island, excavated by the Italian school shortly after Knossos

- Malia - the subject of French excavations, a palatial centre which affords a very interesting look into the development of the palaces in the protopalatial period

- Kato Zakros - a palatial site excavated by Greek archaeologists in the far east of the island

- Galatas - the most recently confirmed palatial site

- Agia Triada - an administrative centre close to Phaistos

- Gournia - a town site excavated in the first quarter of the 20th Century by the American School

- Pyrgos - an early minoan site on the south of the island

- Vasiliki - an early minoan site towards the east of the island which gives its name to a distinctive ceramic ware

- Fournu Korfi - a site on the south of the island

- Pseira - island town with ritual sites

- Mount Juktas - the greatest of the Minoan peak sanctuaries by virtue of its association with the palace of Knossos

- Arkalochori - the findsite of the famous Arkalochori Axe

- Karfi - a refuge site from the late minoan period, one of the last of the Minoan sites

Society and culture

The Minoans were primarily a mercantile people engaged in overseas trade. Their culture, from ca 1700 BC onward, shows a high degree of organization.

Many historians and archaeologists believe that the Minoans were involved in the Bronze Age's important tin trade: tin, alloyed with copper apparently from Cyprus, was used to make bronze. The decline of Minoan civilization and the decline in use of bronze tools in favor of superior iron ones seem to be correlated.

The Minoan trade in saffron, which originated in the Aegean basin as a natural chromosome mutation, has left fewer material remains: a fresco of saffron-gatherers at Santorini is well-known. This inherited trade pre-dated Minoan civilization: a sense of its rewards may be gained by comparing its value to frankincense, or later, to pepper. Archaeologists tend to emphasize the more durable items of trade: ceramics, copper, and tin, and dramatic luxury finds of gold and silver.

Objects of Minoan manufacture suggest there was a network of trade with mainland Greece (notably Mycenae), Cyprus, Syria, Anatolia, Egypt, Mesopotamia, and westward as far as the coast of Spain.

Minoan men wore loincloths and kilts. Women wore robes that were open to the navel, leaving their breasts exposed, and had short sleeves and layered flounced skirts. Women also had the option of wearing a strapless fitted bodice, the first fitted garments known in history. The patterns on clothes emphasized symmetrical geometric designs.

The statues of priestesses in Minoan culture and frescoes showing men and women participating in the same sports such as bull-leaping, lead some archaeologists to believe that men and women held equal social status. Inheritance is thought to have been matrilineal. Minoan religion was goddess worship and women are represented as those officiating at religious ceremonies. The frescos include many depictions of people, with the genders distinguished by colour: the men's skin is reddish-brown, the women's white.

Language and writing

Knowledge of the spoken and written language of the Minoans is scant, due to the small number of records found. Sometimes the Minoan language is referred to as Eteocretan, but this presents confusion between the language written in Linear A scripts and the language written in a Euboean- derived alphabet after the Greek Dark Ages. While the Eteocretan language is suspected to be a descendant of Minoan, there is not enough source material in either language to allow conclusions to be made. It also is unknown whether the language written in Cretan hieroglyphs is Minoan. As with Linear A, it is undeciphered and its phonetic values are unknown.

Approximately 3,000 tablets bearing writing have been discovered so far in Minoan contexts. The overwhelming majority are in the Linear B script, apparently being inventories of goods or resources. Others are inscriptions on religious objects associated with cult. Because most of these inscriptions are concise economic records rather than dedicatory inscriptions, the translation of Minoan remains a challenge. The hieroglyphs came into use from MMI and were in parallel use with the emerging Linear A from the eighteenth century BC (MM II) and disappeared at some point during the seventeenth century BC (MM III).

In the Mycenean period, Linear A was replaced by Linear B, recording a very archaic version of the Greek language. Linear B was successfully deciphered by Michael Ventris in the 1950s, but the earlier scripts remain a mystery. Unless Eteocretan truly is its descendant, it is perhaps during the Greek Dark Ages, a time of economic and socio-political collapse, that the Minoan language became extinct.

Art

The great collection of Minoan art is in the museum at Heraklion, near Knossos on the north shore of Crete. Minoan art, with other remains of material culture, especially the sequence of ceramic styles, has allowed archaeologists to define the three phases of Minoan culture (EM, MM, LM) discussed above.

Since wood and textiles have vanished through decomposition, the most important surviving examples of Minoan art are Minoan pottery, the palace architecture with its frescos that include landscapes, stone carvings, and intricately carved seal stones.

In the Early Minoan period ceramics were characterised by linear patterns of spirals, triangles, curved lines, crosses, fishbone motifs, and such. In the Middle Minoan period naturalistic designs such as fish, squid, birds, and lilies were common. In the Late Minoan period, flowers and animals were still the most characteristic, but the variability had increased. The 'palace style' of the region around Knossos is characterised by a strong geometric simplification of naturalistic shapes and monochromatic paintings. Very noteworthy are the similarities between Late Minoan and Mycenaean art.

Religion

The Minoans worshiped goddesses.[2] Although there is some evidence of male gods, depictions of Minoan goddesses vastly outnumber depictions of anything that could be considered a Minoan god. While some of these depictions of women are believed to be images of worshipers and priestesses officiating at religious ceremonies, as opposed to the deity herself, there still seem to be several goddesses including a Mother Goddess of fertility, a Mistress of the Animals, a protectress of cities, the household, the harvest, and the underworld, and more. Some have argued that these are all aspects of a single goddess. They are often represented by serpents, birds, poppies, and a somewhat vague shape of an animal upon the head. Some suggest the goddess was linked to the "Earthshaker", a male represented by the bull and the sun, who would die each autumn and be reborn each spring. Though the notorious bull-headed Minotaur is a purely Greek depiction, seals and seal-impressions reveal bird-headed or masked deities.

Walter Burkert warns:

- "To what extent one can and must differentiate between Minoan and Mycenaean religion is a question which has not yet found a conclusive answer"[3]

and suggests that useful parallels will be found in the relations between Etruscan and Archaic Greek culture and religion, or between Roman and Hellenistic culture. Minoan religion has not been transmitted in its own language, and the uses literate Greeks later made of surviving Cretan mythemes, after centuries of purely oral transmission, have transformed the meager sources: consider the Athenian point-of-view of the Theseus legend. A few Cretan names are preserved in Greek mythology, but there is no way to connect a name with an existing Minoan icon, such as the familiar serpent-goddess. Retrieval of metal and clay votive figures— double axes, miniature vessels, models of artifacts, animals, human figures—has identified sites of cult: here were numerous small shrines in Minoan Crete, and mountain peaks and very numerous sacred caves—over 300 have been explored—were the centers for some cult, but temples as the Greeks developed them were unknown.[4] Within the palace complex, no central rooms devoted to cult have been recognized, other than the center court where youths of both sexes would practice the bull-leaping ritual. It is notable that there are no Minoan frescoes that depict any deities.

Minoan sacred symbols include the bull and its horns of consecration, the labrys (double-headed axe), the pillar, the serpent, the sun-disk, and the tree.

Warfare and "The Minoan Peace"

Though the vision created by Sir Arthur Evans of a pax Minoica, a "Minoan peace", has been criticised in recent years,[5] it is generally assumed there was little internal armed conflict in Minoan Crete itself, until the following Mycenaean period.[6] As with much of Minoan Crete, however, it is hard to draw any obvious conclusions from the evidence. However, new excavations keep sustaining interests and documenting the impact around the Aegean [3]

Many argue that there is little evidence for ancient Minoan fortifications. But as S. Alexiou has pointed out (in Kretologia 8), a number of sites, especially Early and Middle Minoan sites such as Aghia Photia, are built on hilltops or are otherwise fortified. As Lucia Nixon said, "...we may have been over-influenced by the lack of what we might think of as solid fortifications to assess the archaeological evidence properly. As in so many other instances, we may not have been looking for evidence in the right places, and therefore we may not end with a correct assessment of the Minoans and their ability to avoid war."[7].

Chester Starr points out in "Minoan Flower Lovers" (Hagg-Marinatos eds. Minoan Thalassocracy) that Shang China and the Maya both had unfortified centers and yet still engaged in frontier struggles, so that itself cannot be enough to definitively show the Minoans were a peaceful civilization unparalleled in history.

In 1998, however, when Minoan archaeologists met in a conference in Belgium to discuss the possibility that the idea of Pax Minoica was outdated, the evidence for Minoan war proved to be scanty.

Archaeologist Jan Driessen, for example, said the Minoans frequently show ‘weapons’ in their art, but only in ritual contexts, and that “The construction of fortified sites is often assumed to reflect a threat of warfare, but such fortified centers were multifunctional; they were also often the embodiment or material expression of the central places of the territories at the same time as being monuments glorifying and merging leading power” (Driessen 1999, p. 16).

On the other hand, Stella Chryssoulaki's work on the small outposts or 'guard-houses' in the east of the island represent possible elements of a defensive system. Claims that they produced no weapons are erroneous; type A Minoan swords (as found in palaces of Mallia and Zarkos) were the finest in all of the Aegean (See Sanders, AJA 65, 67, Hoeckmann, JRGZM 27, or Rehak and Younger, AJA 102).

Regarding Minoan weapons, however, archaeologist Keith Branigan notes that 95% of so-called Minoan weapons possessed hafting (hilts, handles) that would have prevented their use as weapons (Branigan, 1999). However more recent experimental testing of accurate replicas has shown this to be incorrect as these weapons were capable of cutting flesh down to the bone (and scoring the bone's surface) without any damage to the weapons themselves. Archaeologist Paul Rehak maintains that Minoan figure-eight shields could not have been used for fighting or even hunting, since they were too cumbersome (Rehak, 1999). And archaeologist Jan Driessen says the Minoans frequently show ‘weapons’ in their art, but only in ritual contexts (Driessen 1999). Finally, archaeologist Cheryl Floyd concludes that Minoan “weapons” were merely tools used for mundane tasks such as meat-processing (Floyd, 1999). Although this interpretation must remain highly questionable as there are no parallels of one-meter-long swords and large spearheads being used as culinary devices in the historic or ethnographic record.

About Minoan warfare in general, Branigan concludes that “The quantity of weaponry, the impressive fortifications, and the aggressive looking long-boats all suggested an era of intensified hostilities. But on closer inspection there are grounds for thinking that all three key elements are bound up as much with status statements, display, and fashion as with aggression…. Warfare such as there was in the southern Aegean EBA early Bronze Age was either personalized and perhaps ritualized (in Crete) or small-scale, intermittent and essentially an economic activity (in the Cyclades and the Argolid/Attica) ” (1999, p. 92). Archaeologist Krzyszkowska concurs: “The stark fact is that for the prehistoric Aegean we have no sic direct evidence for war and warfare per se sic” (Krzyszkowska, 1999).

Furthermore, no evidence exists for a Minoan army, or for Minoan domination of peoples outside Crete. Few signs of warfare appear in Minoan art. “Although a few archaeologists see war scenes in a few pieces of Minoan art, others interpret even these scenes as festivals, sacred dance, or sports events” (Studebaker, 2004, p. 27). Although armed warriors are depicted being stabbed in the throat with swords, violence may occur in the context of ritual or blood sport.

Although on the Mainland of Greece at the time of the Shaft Graves at Mycenae, there is little evidence for major fortifications among the Mycenaeans there (the famous citadels post-date the destruction of almost all Neopalatial Cretan sites), the constant warmongering of other contemporaries of the ancient Minoans – the Egyptians and Hittites, for example – is well documented.

Possibility of human sacrifice

Evidence that suggest the Minoans may have performed human sacrifice has been found at three sites: (1) Anemospilia, in a MMII building near Mt. Juktas, interpreted as a temple, (2) an EMII sanctuary complex at Fournou Korifi in south central Crete, and (3) Knossos, in an LMIB building known as the "North House."

The temple at Anemospilia was destroyed by earthquake in the MMII period. The building seems to be a tripartite shrine, and terracotta feet and some carbonized wood were interpreted by the excavators as the remains of a cult statue. Four human skeletons were found in its ruins; one, belonging to a young man, was found in an unusually contracted position on a raised platform, suggesting that he had been trussed up for sacrifice, much like the bull in the sacrifice scene on the Mycenaean-era Agia Triadha sarcophagus. A bronze dagger was among his bones, and the discoloration of the bones on one side of his body suggests he died of blood loss. The bronze blade was fifteen inches long and had images of a boar on each side. The bones were on a raised platform at the center of the middle room, next to a pillar with a trough at its base.

The positions of the other three skeletons suggest that an earthquake caught them by surprise—the skeleton of a twenty-eight year old woman was spread-eagled on the ground in the same room as the sacrificed male. Next to the sacrificial platform was the skeleton of a man in his late thirties, with broken legs. His arms were raised, as if to protect himself from falling debris, which suggests that his legs were broken by the collapse of the building in the earthquake. In the front hall of the building was the fourth skeleton, too poorly preserved to allow determination of age or gender. Nearby 105 fragments of a clay vase were discovered, scattered in a pattern that suggests it had been dropped by the person in the front hall when s/he was struck by debris from the collapsing building. The jar had apparently contained bull's blood.

Unfortunately, the excavators of this site have not published an official excavation report; the site is mainly known through a 1981 article in National Geographic (Sakellarakis and Sapouna-Sakellerakis 1981, see also Rutter[8]).

Not all agree that this was human sacrifice. Nanno Marinatos says the man supposedly sacrificed actually died in the earthquake that hit at the time he died. She notes that this earthquake destroyed the building, and also killed the two Minoans who supposedly sacrificed him. She also argues that the building was not a temple and that the evidence for sacrifice “is far from … conclusive."[9] Dennis Hughes concurs and also argues that the platform where the man lay was not necessarily an altar, and the blade was probably a spearhead that may not have been placed on the young man, but could have fallen during the earthquake from shelves or an upper floor.[10]

At the sanctuary-complex of Fournou Korifi, fragments of a human skull were found in the same room as a small hearth, cooking-hole, and cooking-equipment. This skull has been interpreted as the remains of a sacrificed victim.[11]

In the "North House" at Knossos, the bones of at least four children (who had been in good health) were found which bore signs that "they were butchered in the same way the Minoans slaughtered their sheep and goats, suggesting that they had been sacrificed and eaten. The senior Cretan archaeologist Nicolas Platon was so horrified at this suggestion that he insisted the bones must be those of apes, not humans."[12]

The bones, found by Peter Warren, date to Late Minoan IB (1580-1490), before the Myceneans arrived (in LM IIIA, circa 1320-1200) according to Paul Rehak and John G. Younger.[13] Dennis Hughes and Rodney Castleden argue that these bones were deposited as a 'secondary burial'.[14] Secondary burial is the not-uncommon practice of burying the dead twice: immediately following death, and then again after the flesh is gone from the skeleton. The main weakness of this argument is that it does not explain the type of cuts and knife marks upon the bones.

Architecture

The Minoan cities were connected with stone-paved roads, formed from blocks cut with bronze saws. Streets were drained and water and sewer facilities were available to the upper class, through clay pipes.

Minoan buildings often had flat tiled roofs; plaster, wood, or flagstone floors, and stood two to three stories high. Typically the lower walls were constructed of stone and rubble, and the upper walls of mudbrick. Ceiling timbers held up the roofs.

Palaces

The first palaces were constructed at the end of the Early Minoan period in the third millennium BC (Malia). While it was formerly believed that the foundation of the first palaces was synchronous and dated to the Middle Minoan at around 2000 BC (the date of the first palace at Knossos), scholars now think that palaces were built over a longer period of time in different locations, in response to local developments. The main older palaces are Knossos, Malia, and Phaistos.

The palaces fulfilled a plethora of functions: they served as centres of government, administrative offices, shrines, workshops, and storage spaces (e.g., for grain). These distinctions might have seemed artificial to Minoans.

The use of the term 'palace' for the older palaces, meaning a dynastic residence and seat of power, has recently come under criticism (see Palace), and the term 'court building' has been proposed instead. However, the original term is probably too well entrenched to be replaced. Architectural features such as ashlar masonry, orthostats, columns, open courts, staircases (implying upper stories), and the presence of diverse basins have been used to define palatial architecture.