Hobartimus (talk | contribs) Undid revision 348120094 by 71.192.241.118 (talk) rv sockpuppet |

79.117.135.104 (talk) temesvar |

||

| (One intermediate revision by one other user not shown) | |||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

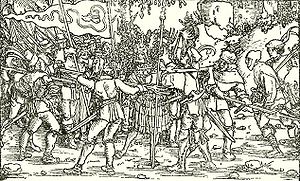

[[Image:Derkovits-dozsa05.jpg|thumb|300px|right|''Dózsa'', by [[Gyula Derkovits]].]] |

[[Image:Derkovits-dozsa05.jpg|thumb|300px|right|''Dózsa'', by [[Gyula Derkovits]].]] |

||

'''György Dózsa''' (1470 - 20 July 1514) was a [[Székely]] Hungarian [[man-at-arms]] (and by some accounts, a [[Nobility and Royalty of the Kingdom of Hungary|nobleman]]) from [[Transylvania]] who led a [[Popular revolt in late medieval Europe|peasants' revolt]] against the [[Kingdom of Hungary|Hungarian]] [[landed nobility]]. He was eventually caught, tortured, and executed along with his followers, and remembered as both a [[Christianity|Christian]] [[martyr]] and a dangerous criminal. During the reign of king [[Vladislas II of Hungary]] (1490–1516), royal power declined in favour of the magnates, who used their power to curtail the peasants’ freedom.<ref>http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/170596/Dozsa-Rebellion</ref> |

'''György Dózsa''' (or, in some sources, ''György Székely''; 1470 - 20 July 1514) was a [[Székely]] Hungarian [[man-at-arms]] (and by some accounts, a [[Nobility and Royalty of the Kingdom of Hungary|nobleman]]) from [[Transylvania]] who led a [[Popular revolt in late medieval Europe|peasants' revolt]] against the [[Kingdom of Hungary|Hungarian]] [[landed nobility]]. He was eventually caught, tortured, and executed along with his followers, and remembered as both a [[Christianity|Christian]] [[martyr]] and a dangerous criminal. During the reign of king [[Vladislas II of Hungary]] (1490–1516), royal power declined in favour of the magnates, who used their power to curtail the peasants’ freedom.<ref>http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/170596/Dozsa-Rebellion</ref> |

||

==Outbreak of the rebellion== |

==Outbreak of the rebellion== |

||

| Line 23: | Line 23: | ||

In the course of the summer he took the fortresses of Arad, [[Lipova, Arad|Lipova]] and [[Şiria, Romania|Şiria]], and provided himself with [[cannon]]s and trained gunners; and one of his bands advanced to within 25 kilometers of the capital. But his ill-armed ploughmen were overmatched by the [[heavy cavalry]] of the nobles. Dózsa himself had apparently become demoralized by success: after [[Cenad]], he issued proclamations which can be described as [[Millenarianism|millenarian]]. |

In the course of the summer he took the fortresses of Arad, [[Lipova, Arad|Lipova]] and [[Şiria, Romania|Şiria]], and provided himself with [[cannon]]s and trained gunners; and one of his bands advanced to within 25 kilometers of the capital. But his ill-armed ploughmen were overmatched by the [[heavy cavalry]] of the nobles. Dózsa himself had apparently become demoralized by success: after [[Cenad]], he issued proclamations which can be described as [[Millenarianism|millenarian]]. |

||

As his suppression had become a political necessity, he was routed at [[Timişoara]] by the combined forces of [[John Zápolya]] and [[István Báthory]]. He was captured after the battle, and condemned to sit on a heated smoldering iron throne with a heated iron crown on his head and a heated sceptre in his hand (mocking at his ambition to be king). While Dózsa was suffering, he was set upon and eaten by six of his fellow rebels, who had been starved beforehand. His execution, and the brutal suppression of the peasants, greatly aided the 1526 Turkish invasion as the Hungarians were no longer a politically united people. The Ottoman Turks were thus able to enter the country posing to some degree as saviors of an oppressed peasantry. |

As his suppression had become a political necessity, he was routed at Temesvár (today [[Timişoara]]) by the combined forces of [[John Zápolya]] and [[István Báthory]]. He was captured after the battle, and condemned to sit on a heated smoldering iron throne with a heated iron crown on his head and a heated sceptre in his hand (mocking at his ambition to be king). While Dózsa was suffering, he was set upon and eaten by six of his fellow rebels, who had been starved beforehand. His execution, and the brutal suppression of the peasants, greatly aided the 1526 Turkish invasion as the Hungarians were no longer a politically united people. The Ottoman Turks were thus able to enter the country posing to some degree as saviors of an oppressed peasantry. |

||

Today, on the site of the martyrdom of the hot throne, there is the statue of [[Blessed Virgin Mary|The Virgin Mary]], built by architect [[László Székely]] and sculptor [[György Kiss]]. According to the legend, during György Dózsa's torture, some monks saw in his ear the image of Mary. The first statue was raised in 1865, with the actual monument raised in 1906. A square, a road and a [[List of metro stations in Budapest|metro station]] in [[Budapest]] (''[[Dózsa György út]]'') bear his name, and it is one of the most popular [[street name]]s in Hungarian villages (alongside [[Sándor Petőfi]]'s and [[Lajos Kossuth]]'s). Many cities in Romania have a ''Gheorghe Doja'' street, as his revolutionary image and Transylvanian background have been heavily used by the country's [[Communist Romania|communist regime]]. Hungarian opera composer [[Ferenc Erkel]] wrote an opera about him (see ''[[György Dózsa (opera)|Dózsa György]]''). |

Today, on the site of the martyrdom of the hot throne, there is the statue of [[Blessed Virgin Mary|The Virgin Mary]], built by architect [[László Székely]] and sculptor [[György Kiss]]. According to the legend, during György Dózsa's torture, some monks saw in his ear the image of Mary. The first statue was raised in 1865, with the actual monument raised in 1906. A square, a road and a [[List of metro stations in Budapest|metro station]] in [[Budapest]] (''[[Dózsa György út]]'') bear his name, and it is one of the most popular [[street name]]s in Hungarian villages (alongside [[Sándor Petőfi]]'s and [[Lajos Kossuth]]'s). Many cities in Romania have a ''Gheorghe Doja'' street, as his revolutionary image and Transylvanian background have been heavily used by the country's [[Communist Romania|communist regime]]. Hungarian opera composer [[Ferenc Erkel]] wrote an opera about him (see ''[[György Dózsa (opera)|Dózsa György]]''). |

||

Revision as of 07:09, 9 March 2010

György Dózsa (or, in some sources, György Székely; 1470 - 20 July 1514) was a Székely Hungarian man-at-arms (and by some accounts, a nobleman) from Transylvania who led a peasants' revolt against the Hungarian landed nobility. He was eventually caught, tortured, and executed along with his followers, and remembered as both a Christian martyr and a dangerous criminal. During the reign of king Vladislas II of Hungary (1490–1516), royal power declined in favour of the magnates, who used their power to curtail the peasants’ freedom.[1]

Outbreak of the rebellion

Born in Dálnok (today Dalnic), Dózsa was a soldier of fortune who won a reputation for valour in the wars against the Ottoman Empire. The Hungarian chancellor, Tamás Bakócz, on his return from the Holy See in 1514 (with a papal bull issued by Leo X authorising a crusade against the Ottomans), appointed Dózsa to organize and direct the movement. Within a few weeks he had gathered an army of some 100,000 so-called Kurucs, consisting for the most part of peasants, wandering students, friars, and parish priests - some of the lowest-ranking groups of medieval society. They assembled in their counties, and by the time Dózsa had provided them with some military training, they began to air the grievances of their status.

No measures had been taken to supply these voluntary crusaders with food or clothing; as harvest-time approached, the landlords commanded them to return to reap the fields, and, on their refusing to do so, proceeded to maltreat their wives and families and set their armed retainers upon the local peasantry. Instantly, the movement was diverted from its original object, and the peasants and their leaders began a war of vengeance against the landlords.

Successes

By this time, Dózsa was losing control of the people under his command, who had fallen under the influence of the parson of Cegléd, Lőrinc Mészáros. The rebellion became more dangerous when the towns joined on the side of the peasants, and in Buda and other places the cavalry sent against the Kuruc were unhorsed as they passed through the gates. The rebellion spread quickly, principally in the central or purely Magyar provinces, where hundreds of manor houses and castles were burnt and thousands of the gentry killed by impalement, crucifixion, and other methods. Dózsa's camp at Cegléd was the centre of the Jacquerie, as all raids in the surrounding area had it as their starting point.

In reaction, the papal bull was revoked, and King Vladislaus II issued a proclamation commanding the peasantry to return to their homes under pain of death. By this time the rising had attained the dimensions of a revolution; all the vassals of the kingdom were called out against it, and soldiers of fortune were hired in haste from the Republic of Venice, Bohemia and the Holy Roman Empire. Meanwhile, Dózsa had captured the city and fortress of Cenad, and signalized his victory by impaling the bishop and the castellan.

Subsequently, at Arad, Lord Treasurer István Telegdy was seized and tortured to death. In general, however, the rebels only executed particularly vicious or greedy noblemen; those who freely submitted were released on parole. Dózsa not only never broke his given word, but frequently assisted the escape of fugitives. He was unable to consistently control his followers, however, and many of them hunted down rivals. At first, it also seemed as if the powers in the Kingdom were incapable of coping with him.

Downfall, execution, and legacy

In the course of the summer he took the fortresses of Arad, Lipova and Şiria, and provided himself with cannons and trained gunners; and one of his bands advanced to within 25 kilometers of the capital. But his ill-armed ploughmen were overmatched by the heavy cavalry of the nobles. Dózsa himself had apparently become demoralized by success: after Cenad, he issued proclamations which can be described as millenarian.

As his suppression had become a political necessity, he was routed at Temesvár (today Timişoara) by the combined forces of John Zápolya and István Báthory. He was captured after the battle, and condemned to sit on a heated smoldering iron throne with a heated iron crown on his head and a heated sceptre in his hand (mocking at his ambition to be king). While Dózsa was suffering, he was set upon and eaten by six of his fellow rebels, who had been starved beforehand. His execution, and the brutal suppression of the peasants, greatly aided the 1526 Turkish invasion as the Hungarians were no longer a politically united people. The Ottoman Turks were thus able to enter the country posing to some degree as saviors of an oppressed peasantry.

Today, on the site of the martyrdom of the hot throne, there is the statue of The Virgin Mary, built by architect László Székely and sculptor György Kiss. According to the legend, during György Dózsa's torture, some monks saw in his ear the image of Mary. The first statue was raised in 1865, with the actual monument raised in 1906. A square, a road and a metro station in Budapest (Dózsa György út) bear his name, and it is one of the most popular street names in Hungarian villages (alongside Sándor Petőfi's and Lajos Kossuth's). Many cities in Romania have a Gheorghe Doja street, as his revolutionary image and Transylvanian background have been heavily used by the country's communist regime. Hungarian opera composer Ferenc Erkel wrote an opera about him (see Dózsa György).

References

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)