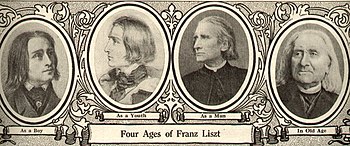

Franz Liszt (Hungarian: Liszt Ferenc; IPA: [ˈlɪst ˈfɛrɛnts]) (October 22 1811– July 31 1886) was a Hungarian composer, teacher and virtuoso of the 19th century. He was a renowned performer throughout Europe, noted especially for his showmanship and great skill with the piano. To this day, he is considered by some to have been the greatest pianist in history.[1] He used both his technique and his concert personality not only for personal effect but also, through his transcriptions, to spread knowledge of other composers' music.[2]

As a composer, Liszt was one of the most prominent representatives of the "Neudeutsche Schule" ("New German School"). He left behind a huge oeuvre, including works from nearly all musical genres. In his compositions he developed new methods, both imaginitive and technical, which influenced his forward-looking contemporaries and anticipated some 20th-century ideas and trends. These included his inventing the symphonic poem for orchestra, evolving the concept of thematic transformation as part of his experiments in musical form and making radical departures in harmony.[3]

Life

Early life

Franz Liszt was born on October 22, 1811, in the village of Raiding (Hungarian: Doborján) in the Kingdom of Hungary, then part of the Habsburg Empire (and today also part of Austria), in the comitat Oedenburg (Hungarian: Sopron). In the vast majority of Liszt literature he is regarded as either Hungarian or German. Every attempt to describe Liszt's development during his childhood and early youth has met with the difficulties of terribly sparse information. It had been Adam Liszt's own dream to become a musician. He played piano, violin, violoncello, and guitar, was in the services of Prince Nikolaus II Esterházy and knew Haydn, Hummel and Beethoven personally.

At age six, Franz began listening attentively to his father's piano playing as well as to show an interest in both sacred and gypsy music. Adam recognized his son's musical talent early. He began teaching Franz the piano at age seven and Franz began composing in an elementary manner when he was eight. He may have also first played in public at Baden at age eight; he definitely appeared in concerts at Sopron and Poszony in October and November 1820. After these concerts, a group of Hungarian magnates offered to finance Franz's musical education abroad.[4]

In Vienna, Liszt received piano lessons from Carl Czerny, who in his own youth had been a student of Ludwig van Beethoven. He also received lessons in composition by Antonio Salieri, who was then music director of the Viennese court. His public debut in Vienna on December 1, 1822, at a concert at the "Landständischer Saal," was a great success. He was greeted in Austrian and Hungarian aristocratic circles and also met Beethoven and Franz Schubert. At a second concert on April 13, 1823, Beethoven was reputed to have kissed Liszt on the forehead. While Liszt himself told this story later in life, this incident may have occurred on a different occasion. Regardless, Liszt regarded it as a form of artistic christening. He was asked by the publisher Diabeli to contribute a variation on a waltz of the publisher's own invention—the same waltz to which Beethoven would write his noted set of 33 variations.[5]

In spring 1823, when the one year's leave of absence came to an end, Adam Liszt asked Prince Esterházy in vain for additional two years. Adam Liszt therefore took his leave of the Prince's services. At the end of April 1823, the family for the last time returned to Hungary. At end of May 1823, the family went to Vienna again.

The child prodigy

On September 20, 1823, the Liszt family left Vienna for Paris. To support himself and his parents, Liszt gave concerts in Munich, Augsburg, Stuttgart and Strasbourg. In Paris, the director of the Conservatoire, Cherubini, refused Liszt admission on the grounds that he was a foreigner. Liszt studied theory with Anton Reicha and composition with Ferdinando Paar.[6]

Liszt was a success in Paris society, playing at many fashionable concerts; his first, on March 7, 1824, was a sensation. In the spring he visited England for the first time. He played at the Argyle Room on June 21 and Drury Lane on June 29. He toured the French provinces the following spring then returned to England, playing in London, in Manchester and before King George IV. He had also been actively composing. While nearly all of those works are lost, some piano works of 1824 were published. These pieces were written in the common style of the contemporary brilliant Viennese school. He had taken works of his former master Czerny as a model, which Liszt's later virtuoso rivals Sigismond Thalberg and Theodor Döhler would also emulate. However, in 1826 he composed the Etude in douze exercises, the original version of the Transcendental Studies. This marked the beginning of Liszt's career as a serious composer.[7]

In 1826 Liszt again toured the French provinces as well as Switzerland that winter. This was followed by a third tour of England. However, the constant touring was beginning to affect the boy's health, plus he expressed a desire to become a priest. [8] In summer 1827, Liszt fell ill.[9] Adam Liszt went with his son to Boulogne-sur-Mer, a spa town on the English Channel. While Liszt himself was recovering, his father Adam fell ill with typhus. On August 28, 1827, Adam Liszt died.

Adolescence in Paris

After his father's death Liszt returned to Paris; for the next five years he was to live with his mother in a small apartment. He gave up touring. To earn money, Liszt gave lessons in piano playing and composition. The following year he fell in love with one of his pupils, Caroline de Saint-Cricq, the daughter of Charles X's minister of commerce. However, her father insisted that the affair be broken off. Liszt again fell ill (there was even an obituary notice of him printed in a Paris newspaper), and he underwent a long period of religious doubts and pessimism. He again stated a wish to join the Church but was dissuaded this time by his mother. He had many discussions with the Abbe de Lamennais, who acted as his spiritual father, and also with Christian Urban, a German-born violinist who introduced him to the Saint-Simonists.[10]

During this period Liszt read widely to overcome his lack of a general education, and he soon came into contact with many of the leading authors and artists of his day, including Victor Hugo, Lamartine and Heine. He composed practically nothing in these years. Nevertheless, the July Revolution of 1830 inspired him to sketch a Revolutionary Symphony based on the events of the "three glorious days," and he took a greater interest in events surrounding him. He met Hector Berlioz on December 4, 1830, the day before the premiere of the Symphonie fantastique. Berlioz's music made a strong impression on Liszt, especially latere when he was writing for orchestra. He also inherited from Berlioz the diabolic quality of many of his works.[11]

After attending an April 20, 1832 charity concert, for the victims of a Parisian cholera epidemic, by Niccolò Paganini,[12] Liszt became determined to become as great a virtuoso on the piano as Paganini was on the violin.[13] In 1833 he made transcriptions of several works by Berlioz, including the Symphonie fantastoque. he was also forming a friendship with the third composer who would influence him, Frederic Chopin; under his influence Liszt's poetic and romantic side began to develop.[14]

With Countess Marie d'Agoult

Since 1833, Liszt's relation with the Countess Marie d'Agoult was developing. In addition to this, at the end of April 1834 he made the acquaintance of Felicité de Lamennais. Under the influence of both, Liszt's creative output exploded. In 1834 Liszt debuted as a mature and original composer with his Harmonies poetiques et religieuses and the set of three Apparitions. These were all poetic works which contrasted strongly with the fantasies he had written earlier.[15]

In 1835 the countess left her husband and family to join Liszt in Geneva; their daughter Blandine was born there on December 18. Liszt taught at the newly-founded Geneva Conservatory wrote a manual of piano technique (later lost) and contributed essays for the Paris Revue et gazette musicale. In these essays, he argued for the raising of the artist from the status of a servant to a respected member of the community.[16]

For the next four years Liszt and the countess lived together, mainly in Switzerland and Italy with occasional visits to Paris. During one of these visits in the winter of 1936-7, Liszt participated in a Berlioz concert, gave chamber music concerts and, on March 31, played at Princess belgiojoso's home in a celebrated pianistic duel with Thalberg. Thanberg's reputation was beginning to eclipse Liszt's, but List was the victo He also composed the Album d'un voyager; these were lyrical evocations of Swiss scenes which he later reworked for his first book of Années de Pèlerinage. He wrote the second book of Années in 1837 while in Italy with the countess; he also composed the first version of the Paganini Studies and the 12 grandes etudes, a greatly revised and expanded and revised version of the Etude in douze exerciuses. On Christmas day their second daughter, Cosima, was born at bellagio, on Lake Como. In 1838 Liszt gave concerts in Vienna and various italian cities. he also began what would become a long series of Schubert transcriptions as well as the initial version of the Totentanz.[17]

On May 9, 1839 Liszt and the countess's only son, Daniel, was born, but that autumn relations between them became strained. Liszt heard that plans for a Beethoven monument in Bonn was in danger of collapse for lack of funds and and pledged his support. Doing so meant returning to the life of a touring virtuoso. The countess returned to Paris with the children while Liszt gave six concets in Vienna then toured Hungary. For the next eight years Liszt continued to tour Europe. he spent summer holidays with the countess and their children on the eisland of ninnerwerth on the Rhine until 1844, when the couple finally separated and Liszt took the childrento Paris to see about their education. This was Liszts most brilliant period as a concert pianist. Honors were showered on him and he was adulated everywhere he went.[18]

Liszt in Weimar

In 1847, Liszt gave up public performances on the piano and in the following year finally took up the invitation of Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna of Russia to settle at Weimar, where he had been appointed Kapellmeister Extraordinaire in 1842, remaining there until 1861. During this period he acted as conductor at court concerts and on special occasions at the theatre, gave lessons to a number of pianists, including the great virtuoso Hans von Bülow, who married Liszt's daughter Cosima in 1857 (before she was married to Wagner). He also wrote articles championing Berlioz and Wagner, and produced those orchestral and choral pieces upon which his reputation as a composer mainly rests. His efforts on behalf of Wagner, who was then an exile in Switzerland, culminated in the first performance of Lohengrin in 1850.

Among his compositions written during his time at Weimar are the two piano concertos, No. 1 in E flat major and No. 2 in A major, the Totentanz, the Concerto pathetique for two pianos, the Piano Sonata in B minor, a number of Etudes, fifteen Hungarian Rhapsodies, twelve orchestral symphonic poems, the Faust Symphony and Dante Symphony, the 13th Psalm for tenor solo, chorus and orchestra, the choruses to Herder's dramatic scenes Prometheus, and the Graner Fest Messe. Much of Liszt's organ music also comes from this period, including the well-known Fantasy and Fugue on the chorale Ad nos, ad salutarem undam and Fantasy and Fugue on the Theme B-A-C-H (the latter also arranged for solo piano).

In 1851 he published a revised version of his 1837 Douze Grandes Etudes, now titled Etudes d'Execution Transcendante, and the following year the Grandes Etudes de Paganini (Grand etudes after Paganini), the most famous of which is La Campanella (The Little Bell), a study in octaves, trills and leaps.

Meets Princess zu Sayn-Wittgenstein

Also in 1847, while touring in the Polish Ukraine (then part of the Russian Empire), Liszt met Princess Carolyne zu Sayn-Wittgenstein. The Princess was an author, whose major work was published in 16 volumes, each containing over 1,600 pages. Her long-winded writing style had some effect on Liszt himself. His biography of Chopin(Life of Chopin) and his chronology and analysis of Gypsy music were both written in the Princess's loquacious style (Grove's Dictionary says that she undoubtedly collaborated with him on this and other works). Princess Carolyne lived with Liszt during his years in Weimar.

Failed Marriage Attempt

The Princess eventually wished to marry Liszt, but since she had been previously married and her husband, Russian military officer Prince Nikolaus zu Sayn-Wittgenstein-Ludwigsburg (1812-1864), was still alive, she had to convince the Roman Catholic authorities that her marriage to him had been invalid. After huge efforts and a monstrously intricate process, she was temporarily successful (September 1860). It was planned that the couple would marry in Rome, on October 22, 1861, Liszt's 50th birthday. Liszt having arrived in Rome on October 21, 1861, the Princess nevertheless declined, by the late evening, to marry him. It appears that both her husband and the Czar of Russia had managed to quash permission for the marriage at the Vatican. The Russian government also impounded her several estates in the Polish Ukraine, which made her later marriage to anybody unfeasible.

Later Relations with the Princess

Much later, in a letter of May 30, 1875, she wrote to Eduard Liszt[19] that she had found Liszt to have been ungrateful. While she had spent her money and had lost nearly all of her former fortune, it had been several millions, he had had during all the time of the Weimar years love affairs with other women. Especially in September 1860 there had been an affaire with the singer Emilie Genast. For this reason she had decided that the planned wedding should be cancelled.[20]

The question whether the Princess was correct in her accusations against Liszt, remains open. Regarding Emilie Genast, in the second half of September 1860 she had for a time of about two weeks visited Liszt in Weimar, on his invitation. In the beginning of October she left, travelling to the Rhineland. Liszt composed for her the love song "Wieder möcht' ich Dir begegnen" ("I'm wishing to meet you again"). Besides, he made a new version of his song "Nonnenwerth" as well as orchestrations of the songs "Die junge Nonne", "Gretchen am Spinnrade" and "Mignon" by Schubert. While they were now all dedicated to Emilie Genast, they had in Liszt's youth been strongly correlated with his affair with Marie d'Agoult. "Mignon" has words "Dahin!, dahin möcht' ich mit dir, o mein Geliebter, ziehn!" (She wants to go together with her darling to Italy.) Reflecting this, Liszt also made a new version of his song "Es rauschen die Winde" with words "Dahin, dahin, sind die Tage der Liebe dahin!" ("the days of love are gone"). From those hints no certain conclusion can be drawn, but Liszt seems to have detected a kind of resemblance between Emilie Genast and the young Marie d'Agoult. However, nearly all of Liszt's letters to Emilie Genast, at least 98, have survived, but are still unpublished; so nothing more can be said.

Might the suspicion of the Princess regarding Emilie Genast insofar have been true or false, it is sure that she was not altogether wrong. It is known from Liszt's correspondence with his mother that in the beginning of 1848 he was in Weimar living together with a Madame F... from Frankfurt-am-Main, a former mistress of Prince Wittgenstein. In March 1848, after Liszt had received a letter of the Princess in which she announced her arrival, Madame F... was very hastily transported to Paris. She visited Liszt’s mother as well as his former secretary Belloni and received an amount of money, telling them that she was pregnant by Liszt. In November 1848 she claimed, she had had an abortion, and disappeared. In 1853 or 1854, Liszt's main mistress was in secret Agnes Street-Klindworth. Liszt visited her for a last time in autumn 1861 in Brussels. It is suspected that the father of some of her children was Liszt.

Liszt in Rome

The 1860s were a period of severe catastrophes of Liszt's private life. After he had on December 13, 1859, already lost his son Daniel, on September 11, 1862, also his daughter Blandine died. In letters to friends Liszt afterwards announced, he would retreat to a solitary living. A more precise impression of his ideas can be gained by looking at his works. On October 22, 1862, his 51st birthday, Liszt took his arrangement of the Overture to Wagner's opera "Tannhäuser" and cut the music illustrating Tannhäuser’s living with “Frau Venus” and her ladies away.[21] He had good reasons for identifying him himself with "Tannhäuser". One year earlier he had like "Tannhäuser" travelled from Thuringia to Rome. Like "Tannhäuser", also his sins had not been forgiven, as can be seen from his failed marriage. It was Liszt's conclusion that his sexual life had been the cause of his bad luck. He considered a living of continence and resignation as the only appropriate choice for him. There is little doubt that he was insofar following Princess Wittgenstein's advice. It was her opinion that sexuality was the worst of all evils in the world.[22]

Liszt also searched for an adequate environment. He found it at the monastery Madonna del Rosario, just outside Rome, where on June 20, 1863, he took up quarters in a small, Spartan apartment. He had on June 23, 1857, already joined a Franciscan order.[23] On April 25, 1865, he received from Gustav Hohenlohe the tonsure and a first one of the minor orders of the Catholic Church. Three further minor orders followed on July 30, 1865. Until then, Liszt was Porter, Lector, Exorcist, and Acolyte. While Princess Wittgenstein tried to persuade him to proceed in order to become priest, he did not follow her. In his later years he explained, he had wanted to preserve a rest of his freedom.[24] By chance, there was a worldly counterpoint to Liszt's becoming ecclesiastic. In the second half of 1865 his two "Episoden aus Lenaus Faust" appeared. The first piece, the "1st Mephisto-Waltz", musically paints a vulgar scene in a village inn. Was this coincidence merely an accident[25], the transcriptions of the pieces "Confutatis maledictis" and "Lacrymosa" of Mozart's Requiem, which Liszt made on January 21, 1865[26], were in a better sense characteristic for him. As child prodigy he had been compared and equalled with the child Mozart. While this aspect of his personality had died, he had in 1865 a rebirth as "Abbé Liszt".

During the 1860s in Rome, Liszt's main works were sacral works such as the oratorios "Die Legende von der heiligen Elisabeth" and "Christus" as well as masses such as the "Missa choralis" and the "Ungarische Krönungsmesse". For many of his piano works Liszt also took sacral subjects. Examples are the piece "À la Chapelle Sixtine" on melodies by Mozart and Allegri, the two pieces "Alleluja" and "Ave Maria d'Arcadelt", and the two Legends "St. François d'Assise" and "St. François de Paule, marchant sur les flots". The two pieces "Illustrations de l'Africaine" on melodies by Meyerbeer are at least in parts of a sacral style.[27] The same goes for the transcription of a scene of Verdi's opera "Don Carlos". But, besides, Liszt still composed works on worldly subjects. Examples of this kind are the concert etudes "Waldesrauschen" and "Gnomenreigen" as well as the fantasy on Mosonyi's opera "Szep Ilonka" and the transcription of the final scene "Liebestod" of Wagner's opera "Tristan und Isolde". Further examples are the pieces "Rêverie sur un motif de l'opéra Roméo et Juliette" and "Les sabéennes, Berceuse de l'opéra La Reine de Saba" after Gounod.

At some occasions, Liszt took part in Rome's musical life. On March 26, 1863, at a concert at the Palazzo Altieri, he directed a program of sacral music. The "Seligkeiten" of his "Christus-Oratorio" and his "Cantico del Sol di Francesco d'Assisi", as well as Haydn's "Die Schöpfung" and works by J. S. Bach, Beethoven, Jornelli, Mendelssohn and Palestrina were performed. On January 4, 1866, Liszt directed the "Stabat mater" of his "Christus-Oratorio", and on February 26, 1866, his "Dante-Symphony". There were several further occasions of similar kind, but in comparison with the duration of Liszt's stay in Rome, they were exceptions. Bódog Pichler, who visited Liszt in 1864 and asked him for his future plans, had the impression that Rome's musical life was not satisfying for Liszt.[28]

Threefold life

Liszt returned to Weimar in 1869. He began a series of piano master classes there, which he would teach a few months every year. From 1876 he also taught for several months every year at the Hungarian Music Academy at Budapest. He continued to live part of each year in Rome, as well. Liszt continued this threefold existence, as he is said to have called it, for the rest of his life.

Last years

From 1876 until his death he also taught for several months every year at the Hungarian Conservatoire at Budapest. On July 2, 1881, Liszt fell down the stairs of the Hofgärtnerei in Weimar. Though friends and colleagues had noted swelling in Liszt's feet and legs when he had arrived in Weimar the previous month, Liszt had up to this point been in reasonably good health, his body retained the slimness and suppleness of earlier years. The accident, which immobilized him eight weeks, changed all this. A number of ailments manifested—dropsy, asthma, insomnia, a cataract of the left eye and chronic heart disease. The last mentioned would eventually contribute to Liszt's death. He would become increasingly plagued with feelings of desolation, despair and death—feelings he would continue to express nakedly in his works from this period. As he told Lina Ramann, "I carry a deep sadness of the heart which must now and then break out in sound."[29]

He died in Bayreuth on July 31, 1886, officially as a result of pneumonia which he may have contracted during the Bayreuth Festival hosted by his daughter Cosima. At first, he was surrounded by some of his more adoring pupils, including Arthur Friedheim, Siloti and Bernhard Stavenhagen, but they were denied access to his room by Cosima shortly before his death at 11:30 p.m. He is buried in the Bayreuth cemetery. Questions have been posed as to whether medical malpractice played a direct part in Liszt's demise. At 11:30 Liszt was given two injections in the area of the heart. Some sources have claimed these were injections of morphine. Others have claimed the injections were of camphor, shallow injections of which, followed by massage, would warm the body. An accidental injection of camphor into the heart itself would result in a swift infarction and death. This series of events is exactly what Lina Schmalhaussen describes in the eyewitness account in her private diary, the most detailed source regarding Liszt's final illness.[30]

The virtuoso

Piano recital

Liszt has most frequently been credited to have been the first pianist who gave concerts with programs consisting only of solo pieces. An example is a concert he gave on March 9, 1839, at the Palazzo Poli in Rome. Since Liszt could not find singers who - following the usual habit of the time - should have completed the program, he played four numbers all alone.[31] Also famous is a concert on June 9, 1840, in London. For this occasion, the publisher Frederic Beale suggested the term "recital"[32] which is still in use today.

Some remarks are needed for the purpose of avoiding misunderstandings. The term "recital", as suggested by Beale, was not meant as connotation of a solo concert. It can also be found in announcements of the concerts given by the troop of Lavenu in 1840-41 in Great Britain, in which Liszt took part. The announcements show that "recital" was meant in a sense that Liszt "recited" his pieces instead of just "playing" them. "Recital" in this sense was meant as specific kind of playing a single piece. The programs included further pieces besides, which were played or sung by other artists, sharing the stage with Liszt. But it is true, that on June 9, 1840, in London, Liszt played his program all alone.

Searching for earlier examples, there is a concert which Liszt gave on May 18, 1836, at the Salons Erard in Paris. He had in the beginning of May given concerts in Lyon, and then travelled to Paris where he arrived on May 13. On the following days he met some of his friends, among them Meyerbeer. He invited them to the Salons Erard, for the purpose of playing some of his new compositions to them. The meeting had a duration of an hour[33] during which Liszt played his fantasy on melodies from Bellini’s opera "I Puritani", his fantasy on melodies from Halévy's opera "La Juive" and his fantasy "La serenata e l'orgia" on melodies from Rossini's "Soirées musicales".[34] Might this be regarded as early example for a solo concert, it was an exception of the rarest kind. As usual case at that time, also Liszt's concert programs included not only solo pieces, but further instrumental or vocal pieces besides. Until spring 1840, at his concerts in Prague, Dresden and Leipzig, Liszt kept doing it that way.

On April 20, 1840, at a soiree at the Salons Erard in Paris, Liszt played another exclusive solo program. While this was an exception again, since Liszt himself had invited his audience, the success can be regarded as reason for which on June 9, 1840, Liszt did the same in London. By doing it that way, he could avoid the usual trouble when trying to find other artists who were willing to take part in his concerts. He could also hope to gain more money, since there was no need to share it with anyone.

During the following years of his tours, Liszt gave concerts of different types. He gave solo concerts as well as concerts at which other artists joined him. In parts of his tours he was accompanied by the singer Rubini, later by the singer Ciabatta, with whom he shared the stage. At occasions, also other singers or instrumentalists took part in Liszt's concerts. For the case that an orchestra was available, Liszt had made accompanied versions of some of his pieces, among them the "Hexameron". Most frequently he also played Weber's "Konzertstück" F Minor as well as Beethoven's concerto E-Flat Major ("Emperor") and the Fantasy for piano, chorus and orchestra op.80. Besides, he played some pieces of chamber music, among them Hummel's Septet as well as Beethoven's "Kreutzer-Sonata" op.47, the Quintet in E-flat op.16 and the "Archduke-Trio" op.97.

Regarding Liszt's solo repertoire, his own catalogue of the works he had played in public during 1838-48[35] is strongly exaggerating. Taking the transcriptions of Schubert songs as examples, no less than 50 pieces are mentioned. In reality Liszt had in the vast majority of all his concerts only played the pieces "Erlkönig", "Ständchen (Serenade)" and "Ave Maria". Since spring 1846 he had added one of his two transcriptions of the "Forelle" to his regularly played repertoire.[36] Another example can be found under the headline "Symphonies". While Beethoven's fifth, sixth and seventh symphonies are listed, Liszt had in public only played the last three movements of his arrangement of the sixth symphony. He did it for a last time on January 16, 1842, in Berlin and afterwards dropped it since it was not successful.

Liszt's legendary reputation as "transcendental virtuoso" was based primarily on repeated performances of fewer than two dozen compositions written or arranged by himself or by Beethoven, Chopin, Hummel, Rossini, Schubert, or Weber.[37] Among the most frequently played pieces of this primary repertoire were the Grand Galop chromatique, the Hexameron, the arrangement of the Overture "Guillaume Tell", the Andante final de Lucia di Lammermoor, and the Sonnambula-fantasy. In many of Liszt's programs also the "Réminiscences des Puritains" can be found. In this case it is uncertain whether he actually played the entire fantasy or only a part of it. The last part was in 1841 separately published as "Introduction et Polonaise". When playing this, Liszt used to take a Mazurka by Chopin or his transcription of the Tarantelle from Rossini's "Soirées musicales", in some cases both, as introduction.

Liszt's most frequently played solo pieces by Beethoven were the Sonatas op.27,2 ("Moonlight") and op.26, of which he usually only played the first movement "Andante con variazione". His repertoire of Baroque music was very small. Of Scarlatti, for example, he played for all of his life just a single piece, the "Katzenfuge". His Handel repertoire was restricted to two, and his Bach repertoire to a handful of pieces. The piano works of Haydn and Mozart did not exist in his concerts. While in letters to Schumann Liszt assured, Schumann's and Chopin's piano works were the only ones of interest for him, for all of his life he actually played not more than a single piano work by Schumann in public, and this only at a single event. It was on March 30, 1840, in Leipzig, when he played a selection of 10 pieces of the Carnaval.[38]

Looking at Liszt in his later years, in the 1870s a new development of classical concert life commenced. It was Liszt's former student Hans von Bülow who more and more concentrated on "serious" music. As consequence, nearly all of Liszt's fantasies and transcriptions and even the Hungarian Rhapsodies disappeared from Bülow’s programs. While the impact of von Bülow's new concert style was very strong, Liszt did not take part in this development. Whenever he played in public, he still chose a repertoire most resembling the style which had been in fashion during the time of his youth. Calling Liszt the father of the modern piano recital, as it has frequently been done, would therefore be wrong. His musical habits and also his taste were different from those of our times.

Performing style

Liszt's career as concertizing pianist can be divided into several periods of different characteristics. There was a first period, his time as child prodigy, ending in 1827 with his father's death. Liszt's playing during this period was in reviews described as very brilliant and very precise, like a living metronome. While he was frequently criticized for a lack of expressiveness, contemporaries hoped, he would improve in later times. His repertoire consisted of pieces in the style of the brilliant Viennese school, concertos by Hummel and brilliant works by his former teacher Czerny. It was exactly this style in which also his own published works were written. Liszt's Bride-fantasy, composed in the beginning of 1829, can be regarded as his last work of that style.

In 1832, Liszt started piano practising and composing again. According to a letter to Princess Belgiojoso of October 1839, it had been his plan, to grow as artist so that in the beginning of 1840 he could start a musical career.[39] While much happened which Liszt could not predict, the development of his relation with Marie d'Agoult and the Thalberg encounter, his guess concerning his own development turned out to be correct. During winter 1839-40 his career as travelling virtuoso commenced. In a letter to Marie d'Agoult of December 9, 1839, he wrote, he started playing admirably.[40]

During the early 1830s, with respect of his performing style, Liszt was by contemporaries accused to behave like a charlatan, a bad actor of the province who wanted effects at any cost.[41] With expressions of his face he was pretending he had strong emotions. Looking to heaven, he tried to act as if he was seeking inspiration from above.[42] When playing the first movement of Beethoven's Sonata op.27,2 ("Moonlight"), he added cadenzas, tremolos and trills. By changing the tempo between Largo and Presto, he turned Beethoven's Adagio into a dramatic scene.[43] In his Baccalaureus-letter to George Sand from the beginning of 1837, Liszt admitted that he had done so for the purpose of gaining applause. He promised, he would from now on follow letter and spirit of a score.[44] However, as soon as he had left Paris, it turned out that not much had changed. Especially in Vienna he was praised for the "creativity" with which he "interpreted" the music he played, finding effects of which the composer himself had had no idea.[45]

During the same time, Liszt's development as composer of concert pieces reached from the Clochette-fantasy op.2, composed 1832-34, to the Lucia-fantasy op.13, composed in autumn 1839. While the Clochette-fantasy was composed in a very eccentric style, without much hope of gaining applause from a contemporary audience, the style of the Lucia-fantasy is different. Especially in the first part, as "Andante final" one of Liszt's most frequently played pieces of his concert repertoire, his own creativity as composer was only small. He took a popular scene, the famous Sextet, and made a transcription of it. To this he added a short introduction and a brilliant cadenza as very short middle section. In the second part he made use of the thumbs melody accompanied by large arpeggios, a most successful device of his rival Thalberg's Moïse-fantasy. According to a letter to Tito Ricordi, Liszt wrote the Lucia-fantasy for the purpose of gaining an easy commercial success.[46]

In comparison with the "Andante final", some of the pieces of Liszt's stay in Geneva during 1835-36 are more interesting. An example is the Puritans-fantasy. Large parts were composed with techniques usually being used in the development section of a sonata form. A long middle section leads from the key E-flat Major of the first main part to the key D Major of the Polonaise-finale. It is a sophisticated modulation from A-flat Minor to D Major, while the D Major triad is strictly avoided. However, as it seems, Liszt found not much resonance with it. He more and more skipped the middle section, playing both main parts as separate fantasies instead.[47] In the end, he restricted himself to playing only the last part as "Introduction et Polonaise".

During the tours of the 1840s, Liszt's Glanzzeit, it was never disputed that his technical skills were astonishing. But he was merely considered as fashionable virtuoso entertainer with missing inspiration. While Thalberg's fame as composer was very strong and even Theodor Döhler was quite well recognized, nothing of this kind can be said of Liszt. An example which illustrates it is a review in London's Musical world of Liszt's Fantasy on "Robert le Diable": "We can conceive no other utility in the publication of this piece, than as a diagram in black and white of M. Liszt's extraordinary digital dexterity."[48] The Leipziger Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung, in a review of the Sonnambula-fantasy, sentenced, it was at least not to be feared that any other artist would follow Liszt on his adventurous path.[49]

Liszt himself, in parts of his career, may have been on error when regarding the impression he had made at his concerts. In December 1841 in Leipzig, for example, he thought, his success had been complete. No further opposition was possible at that place.[50] However, the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik, in a review, complained about missing emotions and eccentricities of his playing style.[51] Clara Schumann, in a letter to her friend Emilie List, wrote, it was astonishing that Liszt was not liked in Leipzig. While people had applauded him, nobody had been really charmed. With all his seeking for effects and applause, she for herself could not regard him as true artist.[52]

As soon as Liszt's career as travelling virtuoso had ended, he himself took a critical point of view regarding his former concert activities. Much of his critique can be found in his book about Chopin. According to this, persons had not attended his concerts for the purpose of listening to his music, but in order to have attended them and to be able to talk about them as social events. A couple of measures of a waltz and a fugitive reminding of an emotion had been sufficient for them.

Liszt's virtuosity and technical innovations

Liszt's playing was described as theatrical and showy, and all those who saw him perform were stunned at his unrivalled mastery over the piano. Perhaps the best indication of Liszt's piano-playing abilities comes from his Douze Grandes Etudes and early Paganini Studies, written in 1837 and 1838 respectively, and described by Schumann as "studies in storm and dread designed to be performed by, at most, ten or twelve players in the world". To play these pieces, a pianist must connect with the piano as an extension of his own body (Walker, 1987).

Liszt claimed to have spent ten or twelve hours each day practicing scales, arpeggios, trills and repeated notes to improve his technique and endurance. All of these piano techniques were frequently applied in his compositions, often resulting in music of extreme technical difficulty (his Transcendental Etude No.5 "Feux follets" is an example). He would challenge himself and his immaculate fingering by presenting random problems to his playing.

Perhaps a large contributing factor to Liszt's affinity for extreme technical difficulty was the structure of his own hands. An original 19th century plaster cast of Liszt's right hand has been reproduced, and is now held in the Liszt House at Marienstrasse 17 (also known as the Liszt Museum). The plaster cast reveals that while Liszt's fingers were undoubtedly slender, they were of no exceptionally abnormal length. However, the small "webbing" connectors found between the fingers of any normal hand were practically nonexistent for Liszt. This allowed the composer to cover a much wider span of notes than the average pianist, perhaps even up to 12 whole steps.

During the 1830s and 1840s — the years of Liszt's "transcendental execution" — he revolutionised piano technique in almost every sector. Figures like Rubinstein, Paderewski and Rachmaninoff turned to Liszt's music to discover the laws which govern the keyboard.

While revolutionary and famously spectacular, Liszt's playing was far from mere flash and acrobatics. He also was reported to have played with a depth and nobility of feeling that would move sturdy men to tears. It seems that this quality to his playing may have continued to develop during his life, overtaking the youthful fire and bravura. Indeed, reports of his playing in old age include observations that it was surprisingly and distinctly subtle and poetic, with great purity of tone and effortlessness of execution; in contrast to the more tumultuous so-called "Liszt school" of playing, which by then had already started to become traditional in Europe. Examination of the late piano works seems to back up this expressive requirement, where the composer deliberately rejects the showiness of his earlier works.

Liszt was also a brilliant sight reader and stunned Edvard Grieg in the 1870s by playing his Piano Concerto perfectly by sight. The year before, Liszt played Grieg's violin sonata from sight. Decades earlier Liszt had played Chopin's studies at sight, prompting Chopin to write that he was consumed by envy, and wished to steal from Liszt his manner of playing his own pieces. This is all the more remarkable when one remembers that Liszt was playing at sight from a hand-written manuscript.

Works

- For a list of works, see main articles: List of compositions by Franz Liszt (S.1 - S.350) and also (S.351 - S.999)

Musical works

Although Liszt provided opus numbers for some of his earlier works, they are rarely used today. Instead, his works are usually identified using one of two different cataloging schemes:

- More commonly used in English speaking countries are the "S" or "S/G" numbers (Searle/Grove), derived from the catalogue compiled by Humphrey Searle for Grove Dictionary in the 1960s.[53]

- Less commonly used is the "R" number, which derives from Peter Raabe's 1931 catalogue Franz Liszt: Leben und Schaffen.

Liszt was a prolific composer. Most of his music is for the piano and much of it requires formidable technique. His thoroughly revised masterwork, Années de Pèlerinage ("Years of Pilgrimage") includes arguably his most provocative and stirring pieces. This set of three suites ranges from the pure virtuosity of the Suisse Orage (Storm) to the subtle and imaginative visualizations of artworks by Michaelangelo and Raphael in the second set. Années contains some pieces which are loose transcriptions of Liszt's own earlier compositions; the first "year" recreates his early pieces of Album d'un voyageur, while the second book includes a resetting of his own song transcriptions once separately published as Tre sonetti di Petrarca ("Three sonnets of Petrarch"). The relative obscurity of the vast majority of his works may be explained by the immense number of pieces he composed. In his most famous and virtuosic works, he is the archetypal Romantic composer. Liszt pioneered the technique of thematic transformation, a method of development which was related to both the existing variation technique and to the new use of the Leitmotif by Richard Wagner.

Transcriptions

Liszt's piano works are usually divided into two classes. On the one hand, there are "original works", and on the other hand "transcriptions", "paraphrases" or "fantasies" on works by other composers. Examples for the first class are works such as the piece Harmonies poétiques et religieuses of May 1833 and the Klaviersonate in h-Moll ("Piano Sonata B Minor"). Liszt's transcriptions of Schubert songs, his fantasies on operatic melodies, and his piano arrangements of symphonies by Berlioz and Beethoven are examples for the second class. As special case, Liszt also made piano arrangements of own instrumental and vocal works. Examples of this kind are the arrangement of the second movement "Gretchen" of his Faust Symphony and the first "Mephisto Waltz" as well as the "Liebesträume" and the two volumes of his "Buch der Lieder".

Liszt's composing music on music, being taken as such, was nothing new. As opposite, for several centuries many of the most prominent composers, among them J. S. Bach, Mozart and Beethoven, had done it before him. An example from Liszt's time is Schumann. He composed his Paganini-studies op.3 and op.10. The subject of his Impromptus op.5 is a melody by Clara Wieck, and that of the Etudes symphoniques op.13 a melody by the father of Ernestine von Fricken, Schumann's first bride. The slow movements of Schumann's piano sonatas op.11 and op.22 are paraphrases of own early songs. For the finale of his sonata op.22, Schumann took melodies by Clara Wieck again. His last compositions, written at the sanatorium at Endenich, were piano accompaniments for violin Caprices by Paganini.

After this, it should not be considered as extraordinary when Liszt, although in a different style, did the same. However, he was frequently criticized. A review in the Leipziger Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung of Liszt's concerts in St. Petersburg of spring 1843 may be taken as characteristic example. After Liszt had in highest terms been praised regarding the impression he had made when playing his fantasies, it was to be read:

- To an artist of such talents we must put the claims, being with right enforced on him by the world, at a higher level than that which until now has been reached by him - why is he only moving in properties of others? why does he not give creations of himself, more lasting than those fugitive reminiscences of a prevailing taste are and can be? [...] An artist of that greatness must not pay homage to the prevailing taste of a time, but stand above it!![54]

Also Liszt's mistresses Marie d'Agoult and Princess Wittgenstein wished him to be a "proper" composer with an oeuvre of original pieces. Liszt himself, as it seems, shared their opinion. For many times he assured, his fantasies and transcriptions were only worthless trash. He would as soon as possible start composing his true masterworks.[55] While he actually composed such works, his symphonies after Dante and Faust as well as his Piano Sonata are examples for it, he kept making fantasies and transcriptions until the end of his life.

There is no doubt that it was an easier task for Liszt to make fantasies and transcriptions than composing large scale original works. It was this reason for which Princess Wittgenstein frequently called him "fainéant" ("lazy-bones").[56] But, nevertheless, Liszt invested a particular kind of creativity. Instead of just overtaking original melodies and harmonies, he ameliorated them. In case of his fantasies and transcriptions in Italian style, there was a problem which was by Wagner addressed as "Klappern im Geschirr der Perioden".[57] Composers such as Bellini and Donizetti knew that certain forms, usually periods of eight measures, were to be filled with music. Occasionally, while the first half of a period was composed with inspiration, the second half was added with mechanical routine. Liszt corrected this by modifying the melody, the bass and - in cases - the harmonies.

Many of Liszt's results were remarkable. The Sonnambula-fantasy for example, a concert piece full of charming melodies, could certainly not have been composed neither by Bellini nor by Liszt alone. Outstanding examples are also the Rigoletto-Paraphrase and the Faust-Walzer. The most delicate harmonies in parts of those pieces were not invented by Verdi and Gounod, but by Liszt. Hans von Bülow admitted, that Liszt's transcription of his Dante Sonett "Tanto gentile" was much more refined than the original he himself had composed.[58]

Notwithstanding such qualities, during the first half of the 20th century nearly all of Liszt's fantasies and transcriptions disappeared from the usually played repertoire. Some hints for an explanation can be found in Béla Bartók's essay "Die Musik Liszts und das Publikum von heute" of 1911. Bartók started with the statement, it was most astonishing that a considerable, not to say an overwhelming part of the musicians of his time could not make friends with Liszt's music. While nearly nobody dared to put critical words against Wagner or Brahms, it was common use to call Liszt's works trivial and boring. Searching for possible reasons, Bartók wrote:

- During his youth he [Liszt] imitated the bad habits of the musical dandies of that time - he "rewrote and ameliorated", turned masterworks, which even a Franz Liszt was not allowed to touch, into compositions for the purpose of showing brilliance. He let himself getting influenced by the more vulgar melodic style of Berlioz, by the sentimentalism of Chopin, and even more by the conventional patterns of the Italian style. Traces of those patterns come to light everywhere in his works, and it is exactly this which gives a colouring of the trivial to them.[59]

Following Bartók's lines, in Liszt's Piano Sonata the "Andante sostenuto" in F-Sharp Minor was "of course" banal, the second subject "cantando espressivo" in D Major was sentimentalism, and the "Grandioso" theme was empty pomp. Liszt's Piano concerto in E-flat Major was in most parts only empty brilliance and in other parts salon music. The Hungarian Rhapsodies were to be rejected because of the triviality of their melodies.

It is obvious that Bartók himself did not like much of Liszt's piano works. Taking his point of view, the agreeable part was very small. All fantasies and transcriptions on Italian subjects were, of course, to be neglected. But traces of conventional patterns of the Italian style can also be found in works by Mozart, Beethoven and Schubert, as treated by Liszt. Examples are Mozart's opera "Don Giovanni" and songs like Beethoven's "Adelaïde" and Schubert's "Ave Maria". Liszt's works on French subjects, among them his fantasies on Meyerbeer's operas, were to be suspected to be as vulgar as the style of Berlioz. Everything reminding of Chopin's sentimentalism was as well to be put aside. After this, of Liszt's huge transcriptions oeuvre not much more remained than his arrangements of Beethoven's symphonies, his transcriptions of organ works by Bach, and a selection of his Wagner transcriptions.

As characteristic for tendencies of the early 20th century, there were not only stylistic objections against Liszt's fantasies and transcriptions. Fantasies and transcriptions were in general considered as worthless and not suiting for a "severe" concert repertoire. An example which shows it is the edition of the "Elsa Reger Stiftung" of Max Reger's "complete" piano works. All of Reger's transcriptions of songs by Brahms, Wolff, Strauss and others as well as his arrangements of Bach's organ works were excluded. Liszt's posthumous fate was of similar kind. In 1911, when Bartók wrote his essay, a complete edition of the "Franz Liszt Stiftung" was in work. Of the series projected to include Liszt's fantasies and transcriptions only three volumes were published. They were a first volume with his Wagner transcriptions, and two further volumes with his arrangements of Beethoven's symphonies. All the rest of Liszt's piano works on works by other composers, i. e. several hundreds of pieces, was excluded.

Original songs

Liszt and program music

Liszt, in some of his works, supported the idea of program music. It means that there was a subject of non-musical kind, the "program", which was in a sense connected with a sounding work. Examples are Liszt's Symphonic Poems, his Symphonies after Faust and Dante, his two Legends for piano and many others. This is not to say, Liszt had invented program music. In his essay about Berlioz and the Harold-Symphony, he himself took the point of view that there had been program music in all times. In fact, looking at the first half of the 19th century, there had been Beethoven's Pastoral-Symphony and overtures such as "Die Weihe des Hauses". Beethoven's symphony "Wellingtons Sieg bei Trafalgar" had been very famous. Further examples are works by Berlioz and overtures such as "Meeresstille und glückliche Fahrt" by Mendelssohn. In 1846, César Franck composed a symphonic work "Ce qu'on entend sur la montagne", based on a Victor Hugo poem.[60] The same poem was shortly afterwards taken by Liszt as subject of a symphonic fantasy, an early version of his Symphonic Poem Ce qu'on entend sur la montagne.

As far as there was a radical new idea in the 19th century, it was the idea of "absolute music". This idea was supported by Eduard Hanslick in his thesis "Vom musikalisch Schönen" which was 1854 published with Liszt's help. In a first part of his book, Hanslick gave examples in order to show that music had been considered as language of emotions before. In contrast to this, Hanslick claimed that the possibilities of music were not sufficiently precise. Without neglecting that a piece of music could evoke emotions or that emotions could be an important help for a composer to get inspiration for a new work, there was a problem of intelligibleness. There were the composer's emotions at the one side and emotions of a listener at the other side. Both kinds of emotions could be completely different. For such reasons, understandable program music was by Hanslick regarded as impossible. According to him, the true value of a piece of music was exclusively dependent on its value as "absolute music". It was meant in a sense that the music was heard without any knowledge of a program, as "tönend bewegte Formen" ("sounding moving forms").

An example which illustrates the problem might be Liszt's "La Notte", the second piece of the Trois Odes funèbres. Projected 1863 and achieved 1864, "La Notte" is an extended version of the prior piano piece Il penseroso from the second part of the Années de pèlerinage. According to Liszt's remark at the end of the autograph score, "La Notte" should be played at his own funeral. From this it is clear that "La Notte" ("The night") means "Death". "Il penseroso", "The thinking", could be "Thoughtful" in English. "Thoughtful", the English word, was a nickname, used by Liszt for him himself in his early letters to Marie d'Agoult. In this sense "Il penseroso", i. e. "Thoughtful", means "Liszt". When composing "La Notte", Liszt extended the piece "Il penseroso" by adding a middle section with melodies in Hungarian czardas style. At the beginning of this section he wrote "...dulces moriens reminiscitur Argos" ("...dying, he is sweetly remembering Argos.") It is a quotation from Vergil's Aeneid. Antor, when he dies, thinks back to his homeland Argos in Greece. It was obviously meant in a sense that Liszt wished to be imagined as a person who, when dying, was remembering his own homeland Hungary.[61] There is no doubt that all this was important for Liszt, but hardly anybody, without explanations just listening to the music, will be able to adequately understand it.

Liszt's own point of view regarding program music can for the time of his youth been taken from the preface of the Album d'un voyageur (1837). According to this, a landscape could evoke a certain kind of mood when being looked at. Since a piece of music could also evoke a mood, a mysterious resemblance with the landscape could be imagined. In this sense the music would not paint the landscape, but it would match the landscape in a third category, the mood.

In July 1854 Liszt wrote his essay about Berlioz and the Harold-Symphony which can be taken as his reply to the thesis by Hanslick. Liszt assured that, of course, not all music was program music. If, in the heat of a debate, a person would go so far as to claim the contrary, it would be better to put all ideas of program music aside. But it would be possible to take means like harmonization, modulation, rhythm, instrumentation and others in order to let a musical motif endure a fate.[62] In any case, a program should only be added to a piece of music if it was necessarily needed for an adequate understanding of that piece.

Still later, in a letter to Marie d'Agoult of November 15, 1864, Liszt wrote:

- Without any reserve I completely subscribe the rule of which you so kindly want to remind me, that those musical works which are in a general sense following a program must take effect on imagination and emotion, independent of any program. In other words: All beautiful music must at first rate and always satisfy the absolute rules of music which are not to be violated or prescribed.[63]

This last point of view is very much resembling Hanslick's opinion. It is therefore not surprising that Liszt and Hanslick were not enemies. Whenever they met they did it with nearly friendly manners. In fact, Hanslick never denied that he considered Liszt as composer of genius. He just did not like some of Liszt's works as music.

Late works

With some works from the end of the Weimar years a development commenced during which Liszt drifted more and more away from the musical taste of his time. An early example is the melodrama "Der traurige Mönch" ("The sad monk") after a poem by Nikolaus Lenau, composed in the beginning of October 1860. While in the 19th century harmonies were usually considered as major or minor triads to which dissonances could be added, Liszt took the augmented triad as central chord.

More examples can be found in the third volume of Liszt's Années de Pèlerinage. "Les Jeux d'Eaux à la Villa d'Este" ("The Fountains of the Villa d'Este"), composed in September 1877 and in usual sense well sounding, foreshadows the impressionism of pieces on similar subjects by Debussy and Ravel. But besides, there are pieces like the "Marche funèbre, En mémoire de Maximilian I, Empereur du Mexique" ("Funeral march, In memory of Maximilian I, Emperor of Mexico"),[64] composed 1867, without any stylistic parallel in the 19th and 20th centuries.

At a later step Liszt experimented with "forbidden" things such as parallel 5ths in the "Csardas marcabre"[65] and atonality in the Bagatelle sans tonalité ("Bagatelle without Tonality"). In the last part of his "2de Valse oubliée" ("2nd Forgotten waltz") Liszt composed that he could not find a lyrical melody. Pieces like the "2d Mephisto-Waltz" are shocking with nearly endless repetitions of short motives. Also characteristic are the "Via crucis" of 1878 as well as pieces such as the two Lugubrious Gondolas, Unstern! and Nuages Gris of the 1880s.

Besides eccentricities of such kinds, Liszt still made transcriptions of works by other composers. They are in most cases written in a more conventional style. But also in this genre Liszt arrived at a problematic end. An example from 1885 is a new version of his transcription of the "Pilgerchor" from Wagner's "Tannhäuser". Had the earlier version's title been "Chor der jüngeren Pilger", it was now "Chor der älteren Pilger". In fact, the pilgrims of the new version have become old and very tired. In the old complete-edition of the "Franz Liszt Stiftung" this version was omitted since it was feared, it might throw a bad light on Liszt as composer.

One of the most striking of Liszt's late paraphrases is his setting of the Sarabande and Chaconne from Handel's opera Almira. This transcription was composed in 1879 for his English pupil Walter Bache, and it is the only setting of a baroque piece from Lilszt's late period.[66] Liszt's last song transcription was on Anton Rubinstein's "Der Asra" after a poem by Heine. No words are included, and the keyboard setting is reduced nearly to the absurd. In several parts the melody is missing. One of those parts is that with words, "Deinen Namen will ich wissen, deine Heimath, deine Sippschaft!" ("I want to know your name, your homeland, your tribe!") The answer is given at the song's end, but again without melody, i.e. with unspoken words. "Mein Stamm sind jene Asra, die sterben, wenn sie lieben." ("My tribe are those Asras, who are dying when they love.") Even more hidden, Liszt implemented still another answer in his piece. To the part with the question he put an ossia in which also the original accompaniment has disappeared. As own melody by Liszt, the solitary left hand plays a motive with two triplets, most resembling the opening motive of his Tasso. The key is the Gypsy or Hungarian variant of g-Minor. In this sense it was Liszt's answer that his name was "Tasso", with meaning of an artist of outstanding creativity.[67] His true homeland was art. But besides, he was until the grave "in heart and mind" Hungarian.

Several of Liszt's pupils of the 1880s left behind records from which the pieces played by themselves and their fellow students are known.[68] With very few exceptions, the composer Liszt of the 1870s and 1880s did not exist in their repertoire. When a student, nearly always August Stradal or August Göllerich, played one of his late pieces, Liszt used to give sarcastic comments to it, of the sense, the composer had no knowledge of composition at all. If they would play such stuff at a concert, the papers would write, it was a pity that they had wasted their talents with music of such kinds. Further impressions can be drawn from the edition in twelve volumes of Liszt's piano works at Edition Peters, Leipzig, by Emil Sauer.

Sauer had studied under Liszt in his latest years. But also in his edition the composer Liszt of this time does not exist. In the volume with song transcriptions, the latest pieces are the second version of the transcription of Eduard Lassen's "Löse Himmel meine Seele" ("Heaven, let my soul be free") and the transcription of Schumann's "Frühlingsnacht" ("Night in spring"). Liszt had made both in 1872. In a separate volume with the Années de Pèlerinage, the only piece of Liszt's third volume is "Les Jeux d'Eaux à la Villa d'Este", while all of the rest was excluded. Of Liszt's transcriptions and fantasies on operatic melodies, the "Feierliche Marsch zum Heiligen Gral" of 1882 is present. However, also in this case a problematic aspect is to be found. In the original edition at Edition Schott, Mainz, Liszt - in a note at the bottom of the first page - had asked the player to carefully take notice of the indications for the use of the right pedal. In Sauer's edition, the footnote is included, but Liszt's original pedal indications were substituted with pedal indications by Sauer. There is little doubt that Sauer, as well as several further of Liszt's prominent pupils, was convinced that he himself was a better composer than his old master.[69]

Literary works

Besides his musical works, Liszt wrote essays about many subjects. Most important for an understanding of his development is the article series "De la situation des artistes" ("On the situation of the artists") which 1835 was published in the Parisian Gazette musicale. In winter 1835-36, during Liszt's stay in Geneva, about half a dozen further essays were following. One of them, it should have been published under the name "Emm Prym", was about Liszt's own works and is lost. In the beginning of 1837, Liszt published a review of some piano works of Sigismond Thalberg. The review evoked a huge scandal. In this time Liszt also commenced the series of his "Baccalaureus-letters". After the series had ended in 1841, Liszt planned to publish a collection of revised versions of the "Baccalaureus-letters" as book. But the plan was not realized.

During the Weimar years, Liszt wrote a series of essays about operas, leading from Gluck to Wagner. Also this series should have been published as book; and also this plan was not realized. Besides, Liszt wrote essays about Berlioz and the symphony "Harold in Italy", Robert and Clara Schumann, John Field's nocturnes, songs of Robert Franz, a planned Goethe-Foundation at Weimar, and other subjects. In addition to these essays, Liszt wrote a book about Chopin as well as a book about the Gypsies and their music in Hungary.

While all of those literary works were published under Liszt's name, it is not quite clear which parts of them he had written himself. It is known from his letters that during the time of his youth there had been collaboration with Marie d'Agoult. During the Weimar years it was the Princess Wittgenstein who helped him. In most cases the manuscripts have disappeared so that it is difficult to decide which of Liszt's literary works actually were works of his own. However, until the end of his life it was Liszt's point of view that it was him who was responsible for the contents of those literary works.

During the 1870s Lina Ramann collected the essays published under Liszt's name. Together with a new version of the book about Chopin, translated by La Mara (Maria Lipsius) from French to German, the essays and the book about the Gypsies were in six volumes published in translations by Ramann. After the edition had for a long time been used in Liszt research, it turned out that many translation errors and other defects had occurred. To this comes that Ramann had not detected all of the essays published under Liszt's name. In one case, a review of Charles Alkan's etudes op.15, it is to be suspected that the essay was omitted because it did not suit to the picture Ramann had made herself of Liszt. For reasons of such kind, a new edition, under the leadership of Detlef Altenburg, Weimar, is in work

In his youth, during his stay in Geneva, Liszt wrote a "Manual of Pianoforte Technique" for the Geneva Conservatoire. Although in newer time Alan Walker claimed that the Manual was unlikely to ever have existed,[70] it is well known from Liszt's letters to his mother and further sources that he wrote and completed it. The work is nevertheless lost.[71] In his later years Liszt wrote voluminous "Technische Studien" ("technical exercises") which are now in three volumes available at Editio musica, Budapest. Taking them as music, they are disappointing because Liszt gave nothing more than a collection of technical exercises. Lots of exercises of similar kind by composers such as Herz, Bertini and MacDowell existed besides. Carl Tausig's "Tägliche Studien" are, without doubt, of better use than Liszt's.[citation needed]

Liszt also worked until at least 1885 on a treatise for modern harmony. Pianist Arthur Friedheim, who also served as Liszt's personal secretary, remembered seeing it among Liszt's papers at Weimar. Liszt told Friedheim that the time was not yet ripe to publish the manuscript, titled Sketches for a Harmony of the Future. Unfortunately, this treatise has been lost.

Legacy

Liszt helped found the Liszt School of Music Weimar [2] as well as the Liszt Ferenc Academy of Music in Budapest. Throughout his later years Liszt took on many private students and his influence as a pedagogue was immense. Among his students were Eugen d'Albert, Walter Bache, Arthur Friedheim, Sophie Menter, Moriz Rosenthal, Emil von Sauer, and Alexander Siloti. Currently Liszt is admired for his flamboyant and difficult style of composing.

Media

Template:Multicol Template:Multi-listen start Template:Multi-listen item Template:Multi-listen item Template:Multi-listen item Template:Multi-listen item

Template:Multi-listen item Template:Multi-listen item Template:Multi-listen item Template:Multi-listen item Template:Multi-listen item Template:Multi-listen item Template:Multicol-end Template:Multi-listen end

See also

- List of compositions by Franz Liszt (S.1 - S.350)

- List of compositions by Franz Liszt (S.351 - S.999)

- Category:Compositions by Franz Liszt

- War of the Romantics

References

- ^ An example can be found in: Saffle: Liszt in Germany, p.209. Regarding the 1840s Saffle wrote, "no one disputed seriously that he [Liszt] was the greatest living pianist, probably the greatest pianist of all time." Since Saffle gave no sources, his statement can only be taken as his own point of view. See also: Fétis: Review of the Transcendental Etudes, 1841."

- ^ Searle, New Grove, 11:29.

- ^ Searle, New Grove, 11:28-29.

- ^ Searle, New Grove, 11:29.

- ^ Searle, New Grove, 22:29.

- ^ Searle, New Grove, 11:29.

- ^ Searle, New Grove, 11:29.

- ^ Searle, New Grove, 11:29.

- ^ See: Rellstab: Franz Liszt, p.66.

- ^ Searle, New Grove, 11:30.

- ^ Searle, New Grove, 11:30.

- ^ The date is known from Liszt's pocket calendar.

- ^ It was not extraordinary, since there were many "piano-Paganinis" in those days. Thalberg received that rank from Rossini; see: Mühsam, Gerd: Sigismund Thalberg als Klavierkomponist, Wien 1937, p.100. Chopin, in his letter to Titus Woyciechowski of December 12, 1831, called Kalkbrenner a pianistic equivalent of Paganini. Also Schumann, during parts of his youth, wanted to take Paganini as model.

- ^ Searle, New Grove, 11:30.

- ^ Searle, New Grove, 18:30.

- ^ Searle, New Grove, 11:30.

- ^ Searle, New Grove, 11:30.

- ^ Searle, New Grove, 11:30.

- ^ Eduard Liszt, born January 31, 1817, was the 25th and youngest child of Franz Liszt's grandfather Georg. His mother was Georg List's third wife Magdalene Richter.

- ^ The letter can be found in: Franz Liszt und sein Kreis in Briefen und Dokumenten aus den Beständen des Burgenländischen Landesmuseums, ed. Maria Eckhardt and Cornelia Knotik, Eisenstadt 1983, p.66ff. Also see the letter to Eduard Liszt of December 20, 1861, p.39ff, which shows that the Princess had lost most of her former fortune. She was prepared that after further 6, 8 or 10 years there would be nothing left. While she had owned millions in former times, she would then live in absolute poverty, hoping for some alms from the husband of her daughter. Liszt still owned a sum of about 220,000 Francs, deposed at the bank of Rothschildt in Paris. But this money was in his will destined as gift for his daughters.

- ^ Comp. the description of the manuscript of the "Choeur des Pèlerins, Aus der Oper Tannhäuser von Richard Wagner", in the New Liszt Edition, Vol. II/12, p.XVIIf.

- ^ Many examples can be found in: Ramann: Lisztiana.

- ^ See the document in: Burger: Lebenschronik in Bildern, p.209.

- ^ Comp. Ramann: Lisztiana, p.198.

- ^ Liszt's letter to Alexander Wilhelm Gottschalg of January 25, 1866, in: Jung: Franz Liszt in seinen Briefen, p.202, shows that the publisher Julius Schuberth was responsible for the coincidence. The piece had already been composed at end of the Weimar years.

- ^ For the date, see: New Liszt Edition, Vol.II/24, p.176. Liszt might have thought of Mozart's birthday, which was on January 27.

- ^ The first piece is a prayer, and the second piece has two choral episodes.

- ^ [Sources for this paragraph will be added later.]

- ^ Walker: Final Years.

- ^ Walker: Final Years, p.508, p.515 with n.18).

- ^ Comp.: Óváry: Ferenc Liszt, p.147.

- ^ Comp.: Walker: Virtuoso years, p.356.

- ^ See the diary entry of May 18, 1836, in: Meyerbeer, Giacomo: Briefwechsel und Tagebücher, mit Unterstützung der Akademie der Künste Berlin in Verbindung mit dem Staatl. Institut für Musikforschung Berlin herausgegeben und kommentiert von Heinz Becker und Gudrun Becker, Band 2 (1825-1836), Berlin 1970, p.523.

- ^ While Walker, in Virtuoso years, p.236, claims, Liszt's program had been "severe", his true repertoire is known from his letter to Marie d'Agoult of May 22, 1836, in: Liszt-d'Agoult: Correspondance I, p.164, and a review by Berlioz in the Revue et Gazette musicale of June 12, 1836. According to Liszt's letter, he had played a "morceau de Rubini", his fantasy "La Juive" and his fantasy "La serenata e l'orgia". A comparison with the review shows that the "morceau de Rubini" must have been identic with a piece called "fantaisie sur le Pirate". The review was in a translation to German republished by Lina Ramann in the first volume of her Franz Liszt als Künstler und Mensch. In his own copy of Ramann's book, p.423, Liszt corrected it, exchanging "Piraten" with "Puritaner". The "morceau de Rubini" therefore was Liszt's fantasy on "I Puritani".

- ^ Comp.: Walker: Virtuoso years, p.445ff.

- ^ According to: Walker: Virtuoso years, p.291, Liszt had already in summer 1844 in Marseille played an own transcription of the "Forelle". However, Walker's source, cited in his n.17, shows that Liszt played Stephen Heller's Caprice op.33 on Schubert's song instead.

- ^ Comp.: Saffle: Liszt in Germany, p.185ff.

- ^ In Liszt's catalogue also the Sonata in F-sharp Minor is listed. This might have been a slip of his memory. In the beginning of 1837 he had planned to play the Sonata, but actually never done it.

- ^ See: Ollivier (ed.): Autour de Madame d’Agoult et de Liszt, p.158f.

- ^ See: Liszt-d'Agoult: Correspondance I, p.327.

- ^ For example, see: Duverger, Franz Liszt, p.140. The book was in May 1843 published with consent of Liszt who read it before publication.

- ^ See the description in Le Pianiste of March 20, 1835, p.77.

- ^ See the description of Berlioz in his essay about Beethoven's Trios and Sonatas, in: Musikalische Streifzüge, Aus dem Französischen übertragen von Ely Ellès, Leipzig 1912, p.52f.

- ^ See: Revue et Gazette musicale 1837, p.55.

- ^ For example, see the review by Heinrich Adami, in Legány: Unbekannte Presse und Briefe, p.28f.

- ^ See: Tibaldi-Chiesa, Mary: Franz Liszt in Italia, in: Nouva Antologia 386 (1936), p.145.

- ^ As an example, see the review of a concert in Derby on September 10, 1840, in: Liszt’s British Tours: Reviews and Letters (ii), in: Liszt Society Journal 9 (1984), p.9.

- ^ Quoted after: Saffle: Liszt in Germany, p.211, n.19.

- ^ See: Leipziger Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung 44 (1842), p.679.

- ^ See: Liszt-d'Agoult: Correspondance II, p.185.

- ^ See: Neue Zeitschrift für Musik 15 (1841), p.191.

- ^ See: Schumann, Clara: „Das Band der ewigen Liebe“: Briefwechsel mit Emilie und Elise List, ed. Eugen Wendler, Stuttgart, Weimar 1996, p.107.

- ^ Searle, Humphrey: The Music of Liszt, pp. 155-156, Dover Publications, 1967. See also [1].

- ^ Translated from German after Leipziger Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung 41 (1842), p.478f.

- ^ For example, see his letter to Marie d'Agoult of October 8, 1846, in: Liszt-d'Agoult: Correspondance II, p.386f. Liszt called his transcriptions oeuvre his "menu fretin", i. e. his "worthless trash". He announced, he would completely ceise this kind of occupation in favour of exclusively composing original works.

- ^ For example, see: Ramann: Lisztiana, p.118, where Liszt complained about the Princess who treated him like a naughty child, called him "fainéant", always trying to force him to compose large scale masterworks. Also see the letter of the Princess to Ramann of August 12, 1881, p.174, where the Princess complained about Liszt who wasted his time, still making piano arrangements, "that equivalent of knitting", instead of composing original works.

- ^ While "Klappern" is "ratteling" or "clattering" and "Geschirr" is "dishes", "Klappern im Geschirr" is a German idiom with meaning, a thing was not properly made. Being taken literally, it can be imagined as a badly made cupboard in which the dishes are clattering when opening or closing a door.

- ^ Comp. his letter to Louise von Welz of December 13, 1875, in: Bülow, Hans von: Briefe, Band 5, ed. Marie von Bülow, Leipzig 1904, p.321.

- ^ Translated from German after: Bartók, Béla: Die Musik Liszts und das Publikum von heute", in: Hamburger, Klara (ed.): Franz Liszt, Beiträge von ungarischen Autoren, Budapest 1978, p.119.

- ^ See the preface of a new edition of C. Franck's Symphonic Poem Les Éolides

- ^ See: Redepenning: Das Spätwerk, p.176ff.

- ^ In August 1854 Liszt started composing his ‘’Faust-Symphony’’.

- ^ Translated from French, after: Liszt-d'Agoult: Correspondance II, p.411.

- ^ The inscription "In magnis et voluisse sat est" ("In great things, to have wished them is sufficient") had in Liszt's youth been correlated with his friend Felix Lichnowski.

- ^ Liszt wrote to the cover of the manuscript, "Darf man solch ein Ding schreiben oder anhören?" ("Is it allowed to write such a thing or to listen to it?")

- ^ Baker, James M., The Cambridge Companion to Liszt, 103.

- ^ It is well known that Liszt identified him himself with Tasso. For this reason, the third piece of the Trois odes funèbres, following "La Notte", is "La triomphe funèbre du Tasso". Liszt hoped that he, like Tasso,would posthumously be recognized as the creative artist he actually was.

- ^ For example, see: Jerger (ed.): Diary Notes of August Göllerich.

- ^ Sauer, in his memoirs, threw even on Liszt as a pianist a sceptical light. While he found it fascinating when Arthur Friedheim was thundering Liszt's Lucrezia-fantasy, Liszt's own playing of a Beethoven sonata received a comment after which it had at least been respectable when being taken as performance of an actor.

- ^ Comp.: Walker: Weimar Years, p. 216.

- ^ For more details see: Bory: Une retraite romantique, p.50f.

Bibliography

- Bory, Robert: Diverses lettres inédites de Liszt, in: Schweizerisches Jahrbuch für Musikwissenschaft 3 (1928).

- Bory, Robert: Une retraite romantique en Suisse, Liszt et la Comtesse d'Agoult, Lausanne 1930.

- Burger, Ernst: Franz Liszt, Eine Lebenschronik in Bildern und Dokumenten, München 1986.

- Chiappari, Luciano: Liszt a Firenze, Pisa e Lucca, Pacini, Pisa 1989.

- d’Agoult, Marie (Daniel Stern): Mémoires, Souvenirs et Journaux I/II, Présentation et Notes de Charles F. Dupêchez, Mercure de France 1990.

- Dupêchez, Charles F.: Marie d’Agoult 1805-1876, 2e édition corrigée, Paris 1994.

- Gut, Serge: Liszt, De Falois, Paris 1989.

- Jerger, Wilhelm (ed.): The Piano Master Classes of Franz Liszt 1884-1886, Diary Notes of August Gollerich, translated by Richard Louis Zimdars, Indiana University Press 1996.

- Jung, Franz Rudolf (ed.): Franz Liszt in seinen Briefen, Berlin 1987.

- Keeling, Geraldine: Liszt’s Appearances in Parisian Concerts, Part 1: 1824-1833, in: Liszt Society Journal 11 (1986), p.22ff, Part 2: 1834-1844, in: Liszt Society Journal 12 (1987), p.8ff.

- Legány, Deszö: Franz Liszt, Unbekannte Presse und Briefe aus Wien 1822-1886, Wien 1984.

- Liszt, Franz: Briefwechsel mit seiner Mutter, edited and annotated by Klara Hamburger, Eisenstadt 2000.

- Liszt, Franz and d'Agoult, Marie: Correspondence, ed. Daniel Ollivier, Tome 1: 1833-1840, Paris 1933, Tome II: 1840-1864, Paris 1934.

- Marix-Spire, Thérése: Les romantiques et la musique, le cas George Sand, Paris 1954.

- Mendelssohn Bartholdy, Felix: Reisebriefe aus den Jahren 1830 bis 1832, ed. Paul Mendelssohn Bartholdy, Leipzig 1864.

- Ollivier, Daniel: Autour de Mme d’Agoult et de Liszt, Paris 1941.

- Óvári, Jósef: Ferenc Liszt, Budapest 2003.

- Protzies, Günther: Studien zur Biographie Franz Liszts und zu ausgewählten seiner Klavierwerke in der Zeit der Jahre 1828 - 1846, Bochum 2004.

- Raabe, Peter: Liszts Schaffen, Cotta, Stuttgart und Berlin 1931.

- Ramann, Lina: Liszt-Pädagogium, Reprint of the edition Leipzig 1902, Breitkopf & Härtel, Wiesbaden, 1986.

- Ramann, Lina: Lisztiana, Erinnerungen an Franz Liszt in Tagebuchblättern, Briefen und Dokumenten aus den Jahren 1873-1886/87, ed. Arthur Seidl, text revision by Friedrich Schnapp, Mainz 1983.

- Redepenning, Dorothea: Das Spätwerk Franz Liszts: Bearbeitungen eigener Kompositionen, Hamburger Beiträge zur Musikwissenschaft 27, Hamburg 1984.

- Rellstab, Ludwig: Franz Liszt, Berlin 1842.

- ed Sadie, Stanley, The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, First Edition (London: Macmillian, 1980). ISBN 0-333-23111-2

- Searle, Humphrey, "Liszt, Franz"

- Sand, George: Correspondence, Textes réunis, classés et annotés par Georges Lubin, Tome 1 (1812-1831), Tome 2 (1832-Juin 1835), Tome 3 (Juillet 1835-Avril 1837), Paris 1964, 1966, 1967.

- Saffle, Michael: Liszt in Germany, 1840-1845, Franz Liszt Studies Series No.2, Pendragon Press, Stuyvesant, NY, 1994.

- Schilling, Gustav: Franz Liszt, Stuttgart 1844.

- Vier, Jacques: Marie d’Agoult - Son mari – ses amis: Documents inédits, Paris 1950.

- Vier, Jacques: La Comtesse d’Agoult et son temps, Tome 1, Paris 1958.

- Vier, Jacques: L’artiste - le clerc: Documents inédits, Paris 1950.

- Walker, Alan: Franz Liszt, The Virtuoso Years (1811-1847), revised edition, Cornell University Press 1987.

- Walker, Alan: Franz Liszt, The Weimar Years (1848-1861), Cornell University Press 1989.

- Walker, Alan: Franz Liszt, The Final Years (1861-1886), Cornell University Press 1997.