Drug Abuse Resistance Education, better known as DARE or D.A.R.E., is an international education program that seeks to prevent use of illegal drugs, membership in gangs, and violent behavior. DARE, which has expanded globally since its founding in 1983, is the major demand-side drug control strategy of the U.S. War on Drugs. Students who enter the latest of over a dozen versions of the program sign a pledge to never use drugs or join gangs and are taught by local law enforcement about the dangers of drug use in a high-tech, interactive, ten week in-school curriculum. According to the D.A.R.E. website, 36 million children around the world — 26 million in the U.S. — are part of the program. The program is implemented in 80% of the nation's school districts, and 54 countries around the world.[1]

Overview

D.A.R.E. America, a national non-profit organization, is the main resource center that manages the program, provides officer training, supports the development and evaluation of the D.A.R.E. curriculum, markets student educational materials, sells D.A.R.E.-branded products, monitors instruction standards and program results, and maintains awareness of the program. The D.A.R.E. program has received numerous accolades and awards for delivering the message to keep "kids off drugs."[1]

D.A.R.E. was one of the first national programs promoting zero tolerance. Some alternative programs advocate a harm reduction approach to drugs. [2]

D.A.R.E. curriculum

The instructors of the D.A.R.E. curriculum are local police officers who must undergo 80 hours of special training in areas such as child development, classroom management, teaching techniques, and communication skills. For high school instructors, 40 hours of additional training are prescribed. [1][3] Police officers are invited by the local school districts to speak and work with students. Police officers are permitted to volunteer in the classroom by the school district and do not need to be licensed teachers. There are programs for different age levels. Working with the classroom teachers, students work over a number of sessions on workbooks and interactive discussions.

The course is complemented by a variety of activities aimed at children, such as D.A.R.E. songs which the students sing together, role-playing, as well as picture storybooks.

Elementary students are given lessons about the effects of [4]

- Tobacco smoking and Tobacco advertising

- Drug abuse

- Inhalant abuse

- Alcohol consumption and health

- Peer pressure in a Social network

The senior high school D.A.R.E. project is a reinforcement with the prime lessons for students[5]

- to act in their own best interest when facing high-risk, low-gain choices

- to resist peer pressure and other influences in making their personal choices

History

D.A.R.E. America, a national non-profit organization, was founded in 1983 by Los Angeles Police chief Daryl Gates.[6] Narcotics-related crimes were the main problems that the LAPD faced. D.A.R.E. was based on his contention that the present generation had already surrendered to drug dependency and that the country’s future lies with the readiness of our children to resist involvement. [6] Gates believed that uniformed police officers were the best equipped to deliver the message that drugs are bad.

The Safe and drug-free schools act (Improving America's Schools Act of 1994) provided funding for use in D.A.R.E. programs in the United States.

In 1994, the National Institute of Justice published a summary[7] of a study conducted by the Research Triangle Institute.[8] The study suggested that D.A.R.E. would benefit from a revised curriculum, which was launched in the fall of 1994.

In the 1996 State of the Union address, President Bill Clinton singled out D.A.R.E. for praise: "People like these D.A.R.E. officers are making a real impression on grade-school children that will give them strength to say no when the time comes."[9]

Two years later, the National Institute of Justice presented it’s Report to the United States Congress and concluded that “D.A.R.E. does not work to reduce substance use.” [10]

Since its inception, some school districts and states have implemented other similar programs as part of general health education. The D.A.R.E. program has become one political battleground of the government drug policy.

Funding

One political issue with D.A.R.E. in the United States is the funding. D.A.R.E. draws its funding as a crime prevention initiative that serves the educational community. School districts do not have to pay to have D.A.R.E officers participate in programs. They are funded through the D.A.R.E. America organization and local law enforcement agencies, and other sources. This makes it popular at a local level for teachers and parent groups.

Some replacement programs required district funding and substitute teachers. Cities that have cut D.A.R.E. programs have been able to re-allocate funding and officers for other purposes. State and Federal politics makes a high-visibility program like D.A.R.E. a target for criticism, primarily as its viability as an educational tool.

Criticisms

D.A.R.E. has fallen under heavy criticism from various sources for many reasons. As part of the War on Drugs program, the D.A.R.E. program is on the front line of widely opposed measures. Some critics of the D.A.R.E. program, notably, the Students for Sensible Drug Policy, commonly criticize the government drug policy in general.[11] The most common argument being that just as Prohibition was ineffective against alcohol consumption, so is the War on Drugs ineffective in curbing Recreational drug use. [12]

D.A.R.E. is ineffective and/or has the opposite effect of promoting drug use

The most common criticism of the D.A.R.E program is that it is ineffective, and that there is no proof that students who go through the D.A.R.E. program are any less likely to use drugs.[13] The U.S. Surgeon General's office, the National Academy of Sciences,[14] the U.S. General Accountability Office (GAO), the National Institute of Justice, [15] and the California Legislative Analyst's Office [16] have also concluded that the program is ineffective.[17] Researchers at Indiana University, commissioned by Indiana school officials in 1992, found that those who completed the D.A.R.E. program subsequently had significantly higher rates of hallucinogenic drug use than those not exposed to the program. [18] Research by Dr. Dennis Rosenbaum,[19] found that D.A.R.E. graduates were more likely than others to drink alcohol, smoke tobacco and use illegal drugs. The U.S. General Accountability Office has concluded that the program is sometimes counterproductive in some populations, with those who graduate from D.A.R.E. later having higher rates of drug use.

Psychologist Dr. William Colson has pointed out that D.A.R.E. increases drug awareness so that "as they get a little older, they become very curious about these drugs they've learned about from police officers.” [20] The scientific research evidence to date indicates that the officers are unsuccessful in preventing the increased awareness and curiosity from being translated into illegal use. That fact may explain why some research has found the D.A.R.E. program to be associated with increased use of drugs. The evidence suggests that, by exposing young impressionable children to drugs, the program is in fact encouraging and nurturing drug use.[21]

D.A.R.E. is ineffective in reducing violence

The National Institute of Justice lists D.A.R.E. under the category of “What Doesn’t Work” [22] In 2001, the Surgeon General of the United States, David Satcher M.D. Ph.D., placed the D.A.R.E. program in the category of "Does Not Work." [23]

D.A.R.E. has tried to suppress unfavorable research

An article in Reason Magazine cites that Administrators of the D.A.R.E. program tried in 1994 to suppress unfavorable research in the 1994 study[8][7] conducted by the Research Triangle Institute in 1994. The director of publication of the American Journal of Public Health told USA Today that "DARE has tried to interfere with the publication of this. They tried to intimidate us."[24] When Dateline NBC planned a story on D.A.R.E., the producer received an angry reaction from that organization’s spokesperson. "They worked very hard to get our story suppressed," said the producer.[24] After reporter Dennis Cauchon published a story questioning the effectiveness of D.A.R.E. in USA Today, he received letters from classrooms around the country, all addressed to "Dear DARE-basher," and all using nearly identical language. [24]

After it published a negative story by Stephen Glass about D.A.R.E., Rolling Stone became the defendant in a libel lawsuit as a result. Glass later settled separately with D.A.R.E.[25] The suit against Rolling Stone was dismissed in April 2000.[26] U.S. District Judge Virginia A. Phillips dismissed the suit and said there was "no clear and convincing evidence that Rolling Stone acted with malice when it published freelancer Stephen Glass's article accusing DARE of harassing critics."[27]

D.A.R.E. also attempted unsuccessfully to prevent airing of an episode of the TV series "Murphy Brown," in which she used marijuana for medical purposes on advice of her physician. It was argued that the episode “Sent the wrong message to our children.” [28]

D.A.R.E. teaches misleading information

"In DARE's worldview, Marlboro Light cigarettes, Bacardi rum, and a drag from a joint are all equally dangerous. For that matter, so is snorting a few lines of cocaine." D.A.R.E. "isn't really education. It's indoctrination" [29] and "students have become skeptical of the scare tactics and exaggerated messages practiced in the DARE curriculum" [30] David J. Hanson Ph.D., Professor Emeritus of Sociology at the State University of New York at Potsdam, NY, contends that labeling alcoholic beverages as gateway drugs and also equating alcohol with other drugs is misleading and counterproductive. [31]

D.A.R.E. police officers may be problematic in classrooms

According to Newsweek, some critics of DARE say that "using police, the ultimate symbol of authority, is precisely what many kids rebel against." [32]

Michael Roona, an expert who worked on a DARE revision, warned that "For certain segments of the population… the presence of a cop in the classroom will be problematic" He warns that "the level of trust a youth will have when interacting with a non-judgmental clinical psychologist, teacher, or social worker engaged in a nurturing or therapeutic activity is orders of magnitude greater than they will have when interacting with a law enforcement officer, especially in communities where even honest, hard working, drug free residents see cops as gang members who simply wear different colors than the Crips, Bloods, or Latin Kings." [33]

DARE undermines parental authority and the family

"DARE has always warred on the family, pitting kids against parents" according to Joel Miller, a former aide for the California legislature. He points out that "Children are asked to submit to DARE police officers sensitive written questionnaires that can easily refer to the kids' homes" and that "a DARE lesson called 'The Three R's: Recognize, Resists, Report' … encourages children to tell friends, teachers or police if they find drugs at home." [34]

In addition, "D.A.R.E. officers are instructed to put a ‘D.A.R.E. Box’ in every classroom, into which students may drop 'drug information' or questions under the pretense of anonymity. Officers are instructed that if a student 'makes a disclosure related to drug use,' the officer should report the information to further authorities, both school and police. This apparently applies whether the 'drug use' was legal or illegal, harmless or harmful. In a number of communities around the country, students have been enlisted by the D.A.R.E. officer as informants against their parents." [35]

As a result, "children sometimes confide the names of people they suspect are illegally using drugs. A mother and father in Caroline County, Md., were jailed for 30 days after their daughter informed a police DARE instructor that her parents had marijuana plants in their home, according to a story in The Washington Post in January 1993. The Wall Street Journal reported in 1992 that ‘In two recent cases in Boston, children who had tipped police stepped out of their homes carrying DARE diplomas as police arrived to arrest their parents.’ In 1991, 10-year-old Joaquin Herrera of Englewood, Colo., phoned 911, announced, ‘I'm a DARE kid’ and summoned police to his house to discover a couple of ounces of marijuana hidden in a bookshelf, according to the Rocky Mountain News. The boy sat outside his parents' home in a police patrol car while the police searched the home and arrested the parents. The policeman assigned to the boy's school commended the boy's action." [36]

"In the official DARE Implementation Guide, police officers are advised to be alert for signs of children who have relatives who use drugs. DARE officers are first and foremost police officers and thus are duty-bound to follow up leads that might come to their attention through inadvertent or indiscreet comments by young children." [37]

In the 1930s, the Soviet regime rewarded young children who betrayed to the authorities words of criticism their parents spoke about the great Stalin. "Stalin's idea of a good young Communist demanded . . . the qualities of an enthusiastic young nark " With D.A.R.E., "police and public schools are using methods reminiscent of those used by Stalin in the American war on drugs and leaving a path of devastated families in the wake." [38]

D.A.R.E. wastes both time and money and should be replaced by effective programs

Another criticism is that D.A.R.E. is not only a very expensive program but that it "consumes approximately seventeen hours of academic time that would otherwise be available for science, math, reading or some other academic subject. In the absence of any proof that D.A.R.E. works, this is a substantial sacrifice of valuable school time."[39] "Every dollar spent on D.A.R.E. is a dollar not available for a useful, educationally sound drug education program in schools.” [39]

It is also argued that D.A.R.E. should be replaced by programs of proven effectiveness[40]. The U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) has identified 66 alternative model programs. [41]

D.A.R.E. is not redistributing profits from merchandise sales

The sheriff of Lake County, Florida, explains that "all workbooks, materials and the very popular T-shirts must be purchased by the Sheriff's Office from D.A.R.E. America Inc. Often, the material and T-shirts could be purchased locally at less expense."

He was surprised and disappointed to learn that the not-for-profit D.A.R.E. corporation now also promotes the sale of its merchandise by for-profit businesses. These private companies can make 80% profit. Of the 20% returned to D.A.R.E. America, Inc., by the companies, none is returned to the local areas from which the profits are derived to support the program. [42]

D.A.R.E. retains support in the face of research and criticism

Despite the criticism and notable research facts, D.A.R.E. is completely consistent with the "zero-tolerance orthodoxy of current U.S. drug control policy." According to researcher Dr. D. M. Gorman of the Rutgers University Center of Alcohol Studies, it supports the ideology and the “prevailing wisdom that exists among policy makers and politicians." [43] It also meets the needs of stake holders such as school districts, [44] parents, and law enforcement agencies. “Part of what makes DARE so popular is that participants get lots of freebies. There are fluorescent yellow pens with with the DARE logo, tiny Daren dolls, bumper stickers, graduation certificates, DARE banners for school auditoriums, DARE rulers, pennants, Daren coloring books, and T-shirts for all DARE graduates.” [45]

Psychologists at the University of Kentucky concluded that "continued enthusiasm [for DARE] shows Americans' stubborn resistance to apply science to drug policy." [46]

Positive effects of D.A.R.E.

D.A.R.E. promotes interaction with police officers

The D.A.R.E. program enables students to interact with police officers in a controlled, safe, classroom environment. This helps students and officers meet and understand each other in a friendly manner, instead of having to meet when a student commits a crime, or when officers must intervene in domestic disputes and severe family problems.[47] The Surgeon General reports that positive effects have been demonstrated regarding attitudes towards the police.[23]

D.A.R.E is more than an anti-drug program

It is also a crime and violence prevention education program. The D.A.R.E. program cites cases where assertiveness and self-defense education helped prevent students from being harmed. D.A.R.E. officers also help schools when children are threatened, and their presence helps alleviate concerns about situations like school shootings and other threats of violence to children while at school.[47]

D.A.R.E. promotes drug awareness

Although one of the criticisms of the program is that it makes students aware of drugs they might not otherwise know, and reportedly intrigues them, it also makes students aware of the prevalence so that they are not caught off guard when they are made available to them. The D.A.R.E. officers bluntly address the students about the ramifications of illegal drug use and the forms that it can take. The officers also address the level of crime, drug dealing and drug use at school and the community. The officers also educate students to see through the techniques drug dealers use to increase their customer base by peer pressure and drug addiction. [citation needed]

Supporters of D.A.R.E. believe educating students that alcoholic beverages and cigarettes are illegal substances is appropriate. They contend that underage drinking in the United States and cigarette purchasing are illegal for those of primary education and secondary education school age. Supporters of D.A.R.E. want students to be educated that recreational drug use also is illegal.[citation needed]

D.A.R.E. promotional products

To help market the program, the organization produces and distributes a significant number of promotional items. They are available through the D.A.R.E. web store. As part of the program, municipalities and schools may budget for some of the items to be given to students as part of the program. Playing off the acronym, many of these products bear the sentence "D.A.R.E. to keep kids off drugs" and "D.A.R.E. to SAY NO". [1]

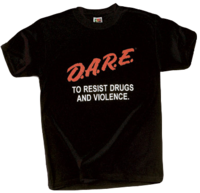

The D.A.R.E. T-Shirt

The D.A.R.E T-shirt is a T-shirt awarded to students in the U.S. and in other countries who complete the D.A.R.E program and pledge to stay drug-free. The D.A.R.E. program now authorizes screen-printers to license their graphics. D.A.R.E. programs can create their own personalized shirts with different colors that incorporate the D.A.R.E. logo and either a school or local police agency logo.

The standard (and most recognized) shirt design is a black tee with the Drug Abuse Resistance Education (D.A.R.E.) logo in red and accompanying text underneath in white printed on the front of the shirt. 'To Keep Kids Off Drugs' or 'To Resist Drugs and Violence' are common phrases printed on the shirt. The D.A.R.E. T-shirt was adopted from the Black concert T-shirt is associated with rock concerts. The classic black t-shirt has become a pop culture icon among youth and young adults in the U.S.

Parody of the shirt

The D.A.R.E. T-shirt has inspired parody T-shirts featuring backronyms such as "Drugs Are Really Excellent". One hemp enthusiast, Mark Hornaday, faced a 4-year prison term and a $20,000 fine from charges filed by the Los Angeles District Attorney's office in 1995. Hornaday created and sold a parody t-shirt, with the inscription, "I turned in my parents and all I got was this lousy t-shirt".[48] NORML defended the suit on free-speech grounds. Charges were eventually dropped.[49]

D.A.R.E. police cars

A number of D.A.R.E. programs in local police departments have some vehicles marked as police cars to promote the program. The D.A.R.E. cars appear at schools and in parades. Typically these cars are high-end or performance cars that have been seized in a drug raid. They are used to send the message that drug dealers forfeit all their glamorous trappings when they get caught. D.A.R.E. cars can also be regular police vehicles that are nearing the end of their service life that are pressed into service for the promotion.

D.A.R.E. in the UK

D.A.R.E. (UK)[50] is a national charity that operates across the UK. The program has been delivered (now discontinued) by Police Officers from the Ministry of Defence Police (MDP) to children who attend schools on Garrison estates or located near Garrison areas.

The D.A.R.E UK program is currently operating in the following areas:

- East Midlands

- South West

- London

- Wales

The program aims to:

- Provide drug education and prevention activities to help children to understand the dangers of the misuse of drugs

- Teach about the harmful effects of drugs, providing information that is appropriate to the age group to which it is delivered

- Develop the life skills to resist peer pressure and personal pressure, and to avoid the misuse of drugs

- Prevention is better than intervention

- Educate primary and secondary school children, therefore preventing many of them from misusing drugs

The Rhondda schools in Wales implemented the D.A.R.E. program, but the Welsh government recommended that for all other schools in Wales, drug and substance abuse programmes should be taught as part of a school’s personal and social education programme as proposed in Circular 17/02 Substance Misuse: Children and Young People. It expressed concern over "the quality and credibility of previous evaluations of the DARE project in other parts of the UK and internationally. These have provided conflicting opinions or proved inconclusive as to its value for money and its long-term-impact in influencing pupils’ attitudes and behaviour towards drug and substance abuse." [51]

See also

- GREAT Program

- Illegal drugs

- Legal issues of cannabis

- Police Athletic League

- Prohibition (drugs)

- Students for Sensible Drug Policy

- War on Drugs

References

- ^ a b c d DARE.com, the official website of the D.A.R.E. program.

- ^ SAFETY FIRST - A REALITY BASED APPROACH to TEENS and DRUGS Dr. Marsha Rosenbaum

- ^ http://www.dare.com/home/about_dare.asp About D.A.R.E.

- ^ Objectives for D.A.R.E. Elementary School Curriculum Lucia Romero. dare.com D.A.R.E. America (Word document)

- ^ D.A.R.E. Senior High Curriculum dare.com D.A.R.E. America. no date "Equal emphasis is placed on helping students to recognize and cope with feelings of anger without causing harm to themselves or others and without resorting to violence or the use of alcohol and drugs."

- ^ a b Los Angeles Police Department - History of the LAPD - Chief Gates

- ^ a b The D.A.R.E.® Program: A Review of Prevalence, User Satisfaction, and Effectiveness Jeremy Travis, director. October 1994 (PDF document) "While not conclusive, the findings suggest that D.A.R.E.® may benefit from using more interactive strategies and emphasizing social and general competencies. A revised D.A.R.E.® curriculum that includes more participatory learning was piloted in 1993 and is being launched nationwide this fall."

- ^ a b Past and Future Directions of the D.A.R.E. Program: An Evaluation Review. Research Triangle Institute Christopher L. Ringwalt, Jody M. Greene, Susan T. Ennett, Ronaldo Iachan, Richard R. Clayton, Carl G. Leukefeld. September 1994 Supported under Award # 91-DD-CX-K053 from the National Institute of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice.

- ^ President William Jefferson Clinton, 1996 State of the Union Address, January 23, 1996

- ^ http://www.ncjrs.gov/works Lawrence W. Sherman et al. for the National Institute of Justice. Preventing Crime: What Works, What Doesn’t, What’s Promising. 1998

- ^ http://daregeneration.blogspot.com D.A.R.E. Generation Diary] blog of the Students for Sensible Drug Policy

- ^ The Lost War - Misha Glenny. Washington Post Sunday, August 19, 2007

- ^ Drug Abuse Resistance Education: the Effectiveness of DARE by David J. Hanson Ph.D. alcoholfacts.org. (website hosted at State University of New York, Potsdam). no date.

- ^ Zernike, K. Anti-drug program says it will adopt a new strategy. New York Times, February 15, 2001.

- ^ http://www.ncjrs.gov/works Lawrence W. Sherman et al. for the National Institute of Justice. Preventing Crime: What Works, What Doesn’t, What’s Promising. 1998

- ^ California Legislative Analyst's Office Analysis of the 2000-2001 Budget Bill. no date

- ^ Kanof, M. E. Youth Illicit Drug Use Prevention: D.A.R.E. Long-Term Evaluations and Federal Efforts to Identify Effective Programs. Washington, DC: General Accounting Office, January 15, 2003. Letter to Senator Richard Durbin "six evaluations we reviewed were based on three separate studies in three states—Colorado, Kentucky, and Illinois. ... Each of the six evaluations, conducted at intervals ranging from 2 to 10 years after the fifth or sixth grade students were initially surveyed, suggested that D.A.R.E. had no statistically significant long-term effect on preventing illicit drug use."pdf format

- ^ Evans, Alice and Kris Bosworth. Building effective drug education programs. Phi Delta Kappa International Research Bulletin No 19, December, 1997.

- ^ Rosenbaum, D. P., and Gordon S. Hanson. Assessing the effects of school-based drug education: A six-year multilevel analysis of project D.A.R.E. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 1998, 35(4), 381-412. abstract, Full text at Schaffer Library of Drug Policy

- ^ Laugesen, W. The dire consequences of DARE. Boulder Weekly, December 4, 1998

- ^ Assessing the effects of School-based Drug Education: A Six-year Multi-Level Analysis of Project D.A.R.E. by Dennis P. Rosenbaum, Ph.D. Professor and Head and Gordon S. Hanson, Ph.D. Research Associate Department of Criminal Justice and Center for Research in Law and Justice University of Illinois at Chicago. April 6, 1998. Media Awareness Project (MAP) Inc. d/b/a DrugSense

- ^ http://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles/171676.PDF National Institute of Justice. ‘’Research in Brief,’’ July, 1998. Summary of its Report to Congress, ‘’Preventing Crime: What Works, What Doesn‘t, What‘s Promising.

- ^ a b Youth Violence: A Report of the Surgeon General Surgeon General of the United States. (David Satcher, M.D., Ph.D., ) 2001., chapter five, Prevention and Intervention, box 5-2

- ^ a b c Drug prevention placebo: How DARE wastes time, money and police. Elliott, Jeff. Reason Magazine, March, 1995.

- ^ [http://www.salon.com/media/lehm/1999/02/04lehm.html Rolling Stone gathers a $50 million lawsuit; Condé Nast's firing line, part 57] Susan Lehman. Salon.com. February 4, 1999

- ^ Judge intends to dismiss libel suit filed by DARE. Los Angeles Times, April 18, 2000

- ^ Judge intends to dismiss libel suit filed by DARE. Los Angeles Times, April 18, 2000, p. 4

- ^ [http://hemptopia.org/wst_page9.html Herer, Jack. The Emperor Wears No Clothes, Quick American Archives, 11th ed., ch. 14]

- ^ Gonnerman, Jennifer. Truth or D.A.R.E.:The Dubious Drug-Education Program Takes New York . Village Voice, 4/7/99

- ^ Does DARE work? What is Wrong With DARE and how can it be Fixed?

- ^ Children and Young People, Effective Alcohol Education: what Works with Underage Youths David J. Hanson Ph.D.

- ^ Kalb, Claudia. DARE Checks Into Rehab. Newsweek, February 26, 2001, 137(9), 56

- ^ Roona, Michael. Drug Abuse Prevention Project Curriculum Workgroup Goals and Recommendation

- ^ Miller, Joel. Bad Trip: How the War Against Drugs is Destroying America. NY: Nelson Thomas, 2004

- ^ Different Look at D.A.R.E.

- ^ Bovard, James. DARE scare: Turning children into informants? Schaffer Library of Drug Policy, 1/29/94

- ^ Bovard, James. Destroying Families for the Glory of the Drug War, Part 1. Freedom Daily, February, 1997

- ^ Bovard, James. Destroying Families for the Glory of the Drug War, Part 1. Freedom Daily, February, 1997

- ^ a b A DIFFERENT LOOK AT D.A.R.E. Stop the Drug War (DRCNet - The Drug Reform Coordination Network). No Date. section six: What's Wrong with DARE?

- ^ Ennett, S.T., Tobler, N.S., Ringwalt, C.L., & Flewelling, R.L. How effective is Drug Abuse Resistance Education? A meta-analysis of project D.A.R.E. outcome evaluations. American Journal of Public Health, 1994, 84(9), 1394-1401.

- ^ http://modelprograms.samhsa.gov/model.htm Model Programs

- ^ Daniels, C. Sheriff upset by DARE’s profit system. Orlando Sentinel, May 7, 2006. The Sheriff is urging people not to purchase DARE materials from anyone other than a law enforcement officer. He reports that otherwise, “buyers will only be lining the pockets of someone out to make a profit, and what little bit of money is passed along to DARE America Inc. will not make it back to our classrooms.”

- ^ Gorman, D. M. Irrelevance of evidence in the development of school-based drug prevention policy. Evaluation Review, 1998, 22(1), 118-146.

- ^ Retsinas, J. Decision to cut off U.S. aid to D.A.R.E. Hailed. Providence Business News, 2001, 15(47), 5B.

- ^ http://www.druglibrary.org/think/~jnr/truthord.htm+DARE+%22Rolling+Stone%22&hl=en&ct=clnk&cd=25&gl=us Gonnerman, Jennifer. Truth or D.A.R.E. :The dubious drug-education program takes New York. Village Voice, April 7, 1999.

- ^ Barry, Ellen. Study adds to doubts on D.A.R.E. program. Boston Globe, 8/2/99, p. A01

- ^ a b D.A.R.E is more than an anti-drug program dare.com. Ralph Lochridge. August 4, 2004. (Microsoft Word document)

- ^ NO JOKING MATTER: Spoof on D.A.R.E. draws ire from cops, prosecution by D.A. By Howard Blume, LA Weekly, November 17 1995

- ^ Charges Dropped Against Shop Owner Who Sold Shirts That Parodied D.A.R.E. Logo

- ^ D.A.R.E UK

- ^ Drug Abuse and Resistance Training (DARE) Report hosted on the Welsh government web site. No date. No author, PDF copy no longer available.