Abraham Lincoln | |

|---|---|

| |

| 16th President of the United States | |

| In office March 4, 1861 – April 15, 1865 | |

| Vice President | Hannibal Hamlin (1861–1865) Andrew Johnson (1865) |

| Preceded by | James Buchanan |

| Succeeded by | Andrew Johnson |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Illinois's 7th district | |

| In office March 4, 1847 – March 3, 1849 | |

| Preceded by | John Henry |

| Succeeded by | Thomas L. Harris |

| Personal details | |

| Born | February 12, 1809 Hardin County, Kentucky |

| Died | April 15, 1865 (aged 56) Washington, D.C. |

| Resting place | Oak Ridge Cemetery Springfield, Illinois 39°49′24″N 89°39′21″W / 39.82333°N 89.65583°W |

| Nationality | American |

| Political party | Whig (1832–1854) Republican (1854–1865) |

| Spouse | Mary Todd Lincoln |

| Relations | Thomas Lincoln (father) Nancy Lincoln (mother) |

| Children | Robert Todd Lincoln Edward Lincoln Willie Lincoln Tad Lincoln |

| Profession | Lawyer Politician |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Branch/service | Illinois Militia |

| Years of service | 1832 |

| Battles/wars | Black Hawk War |

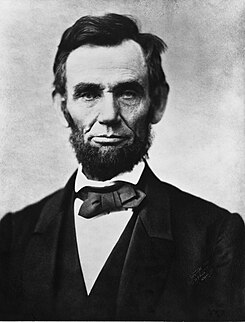

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th President of the United States, serving from March 1861 until his assassination. He successfully led the country through a great constitutional, military and moral crisis—the American Civil War—preserving the Union while ending slavery and promoting economic modernization. Reared in a poor family on the western frontier, he was mostly self-educated. He became a country lawyer, an Illinois state legislator, and a one-term member of the United States House of Representatives but failed in two attempts at a seat in the United States Senate. He was an affectionate, though often absent, husband and father of four children.

After deftly opposing the expansion of slavery in the United States in his campaign debates and speeches,[1] Lincoln secured the Republican nomination and was elected president in 1860. Following declarations of secession by southern slave states, war began in April 1861, and he concentrated on both the military and political dimensions of the war effort, seeking to reunify the nation. He vigorously exercised unprecedented war powers, including the arrest and detention without trial of thousands of suspected secessionists. He prevented British recognition of the Confederacy by skillfully handling the Trent affair late in 1861. He issued his Emancipation Proclamation in 1863 and promoted the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, abolishing slavery.

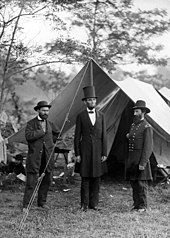

Lincoln closely supervised the war effort, especially the selection of top generals, including the commanding general and future president, Ulysses S. Grant. He brought leaders of various factions of his party into his cabinet and pressured them to co-operate. Under his leadership, the Union took control of the border slave states at the start of the war and tried repeatedly to capture the Confederate capital at Richmond. Each time a general failed, Lincoln substituted another until finally Grant succeeded in 1865. A shrewd politician deeply involved with power issues in each state, he reached out to War Democrats and managed his own re-election in the 1864 presidential election.

As the leader of the moderate faction of the Republican party, Lincoln came under attack from all sides. Radical Republicans wanted harsher treatment of the South, Democrats desired more compromise, and secessionists saw him as their enemy.[2] Lincoln fought back with patronage, by pitting his opponents against each other, and by appealing to the American people with his powers of oratory;[3] for example, his Gettysburg Address of 1863 became one of the most quoted speeches in American history. It was an iconic statement of America's dedication to the principles of nationalism, equal rights, liberty, and democracy. At the close of the war, Lincoln held a moderate view of Reconstruction, seeking to speedily reunite the nation through a policy of generous reconciliation in the face of lingering and bitter divisiveness. Lincoln was shot and killed just six days after the surrender of Confederate commanding general Robert E. Lee, marking the first assassination of a U.S. president. Lincoln has frequently been ranked by a majority of scholars as the greatest U.S. president.

Early life

Abraham Lincoln was born February 12, 1809, the second child of Thomas Lincoln and Nancy Lincoln (née Hanks), in a one-room log cabin on the Sinking Spring Farm in southeast Hardin County, Kentucky[4] (now LaRue County).

Little is known about Lincoln's ancestors. Historical investigations have traced his family back to Samuel Lincoln, an apprentice weaver who arrived in Hingham, Massachusetts, from Norfolk, England, in 1637.[5][6] However, Lincoln himself was only able to trace his heritage back as far as his paternal grandfather and namesake, Abraham Lincoln, a local militia captain and substantial landholder with an inherited 200-acre (81 ha) estate in Rockingham County, Virginia.[5][7] The elder Abraham later moved his family from Rockingham County, Virginia, to Jefferson County, Kentucky,[5][8] where he was ambushed and killed in an Indian raid in 1786 with his children Mordecai, Josiah, and Thomas looking on.[8] Mordecai's marksmanship with a rifle saved Thomas from the same fate. As the eldest son, by law Mordecai inherited his father's entire estate.[9]

Thomas became a respected citizen of rural Kentucky. He bought and sold several farms, including the Sinking Spring Farm. The family attended a Separate Baptists church, which had high moral standards and opposed alcohol, dancing, and slavery,[10] though Thomas, as an adult, never formally joined a church. Thomas enjoyed considerable status in Kentucky – where he sat on juries, appraised estates, served on country patrols, and guarded prisoners. By the time his son Abraham was born, Thomas owned two 600-acre (240 ha) farms, several town lots, livestock, and horses. He was among the richest men in the county.[5][11] In 1816, the Lincoln family lost their lands because of a faulty title and made a new start in Perry County, Indiana (now Spencer County). Lincoln later noted that this move was "partly on account of slavery" but mainly due to land title difficulties.[12]

When Lincoln was nine, his 34-year-old mother died of milk sickness.[13] His older sister, Sarah (Grigsby), died while giving birth at a young age.[6] Soon after, his father married Sarah Bush Johnston, with whom Lincoln became very close and whom he called "Mother."[14] However, he became increasingly distant from his father. Lincoln regretted his father's lack of education and did not like the hard labor associated with frontier life. Still, he willingly took responsibility for all chores expected of him as a male in the household and became an adept axeman in his work building rail fences. Lincoln also agreed with the customary obligation of a son to give his father all earnings from work done outside the home until age 21.[13] In later years, he occasionally loaned his father money.[15]

In 1830, fearing a milk sickness outbreak, the family settled on public land in Macon County, Illinois.[16] In 1831, when his father relocated the family to a new homestead in Coles County, Illinois, 22-year-old Lincoln struck out on his own, canoeing down the Sangamon River to the village of New Salem in Sangamon County.[17] In the spring of 1831, hired by New Salem businessman Denton Offutt and accompanied by friends, he took goods by flatboat from New Salem to New Orleans via the Sangamon, Illinois, and Mississippi rivers. After arriving in New Orleans—and witnessing slavery firsthand—he walked back home.[18]

Lincoln's formal education consisted of approximately 18 months of classes from several itinerant teachers; he was mostly self-educated and was an avid reader.[19] He attained a reputation for brawn and audacity after a very competitive wrestling match to which he was challenged by the renowned leader of a group of ruffians, "the Clary's Grove boys".[20] Some in his family, and in the neighborhood, considered him to be lazy.[21][22] Lincoln avoided hunting and fishing out of an aversion to killing animals.[23]

Marriage and family

Lincoln's first romantic interest was Ann Rutledge, whom he met when he first moved to New Salem; by 1835, they were in a relationship but not formally engaged. She died, however, on August 25, most likely of typhoid fever.[24] In the early 1830s, he met Mary Owens from Kentucky when she was visiting her sister. Late in 1836, Lincoln agreed to a match with Mary if she returned to New Salem. Mary did return in November 1836, and Lincoln courted her for a time; however, they both had second thoughts about their relationship. On August 16, 1837, Lincoln wrote Mary a letter from his law practice in Springfield, suggesting he would not blame her if she ended the relationship. She never replied and the courtship was over.[25] For the next four years Lincoln boarded with his Kentucky gentry friend Joshua Speed in Springfield.[26]

In 1840, Lincoln became engaged to Mary Todd, who was from a wealthy slave-holding family in Lexington, Kentucky.[27] They met in Springfield in December 1839[28] and were engaged the following December.[29] A wedding was set for January 1, 1841, but the couple split as the wedding approached.[28] They later met at a party and then married on November 4, 1842, in the Springfield mansion of Mary's married sister.[30] While preparing for the nuptials and feeling reluctance again, Lincoln, when asked where he was going, replied, "To hell, I suppose."[31]

In 1844, the couple bought a house in Springfield near Lincoln's law office.[32] Mary Todd Lincoln worked diligently in their home, assuming household duties which had been performed for her in her own family. She also made efficient use of the limited funds available from her husband's law practice.[33] One evening, Mary asked Lincoln four times to restart the fire and, getting no reaction as he was absorbed in his reading, she grabbed a piece of firewood and rapped him on the head.[34] The Lincolns had a budding family with the birth of Robert Todd Lincoln in 1843 and Edward Baker Lincoln in 1846. Lincoln, according to those familiar with the family, "was remarkably fond of children,"[35] and the Lincolns were not thought to be strict with their children.[36]

Robert was the only child of the Lincolns to live past the age of 18. Edward Lincoln died on February 1, 1850, in Springfield, likely of tuberculosis.[37] The Lincolns' grief over this loss was somewhat assuaged by the birth of William "Willie" Wallace Lincoln nearly 11 months later, on December 21. However, Willie died of a fever at the age of 11 on February 20, 1862, in Washington, D.C., during President Lincoln's first term.[38] The Lincolns' fourth son, Thomas "Tad" Lincoln, was born on April 4, 1853, and outlived his father but died of heart failure at the age of 18 on July 16, 1871, in Chicago.[39]

The death of their sons had profound effects on both parents. Later in life, Mary struggled with the stresses of losing her husband and sons, and Robert Lincoln committed her temporarily to a mental health asylum in 1875.[40] Abraham Lincoln suffered from "melancholy", a condition which now may be referred to as clinical depression.[41]

Lincoln's father-in-law was based in Lexington, Kentucky; he and others of the Todd family were either slave owners or slave traders. Lincoln was close to the Todds, and he and his family occasionally visited the Todd estate in Lexington; Lincoln's connections in Lexington could have effectuated his ambitions, but he remained in Illinois, where, to his liking, slavery was almost nonexistent.[42]

Early career and militia service

In 1832, at age 23, Lincoln and a partner bought a small general store on credit in New Salem, Illinois. Although the economy was booming in the region, the business struggled and Lincoln eventually sold his share. When his partner later died, Lincoln became liable for a $1,000 debt. Unable to pay, he was forced to declare bankruptcy and did not finish repaying his creditors for another 17 years.[43] That same year he began his political career with a campaign for the Illinois General Assembly. He had attained local popularity and could draw crowds as a natural raconteur in New Salem, though he lacked an education, powerful friends, and money. He advocated navigational improvements on the Sangamon River.[44][45] Before the election, he served briefly as a captain in the Illinois militia during the Black Hawk War, although he never saw combat. Lincoln returned from the militia and was able to campaign for the August 6 election. At 6 feet 4 inches (1.93 metres), he was tall and "strong enough to intimidate any rival." At his first speech, he grabbed an antagonist by his "neck and the seat of his trousers" and threw him. Lincoln finished eighth out of thirteen candidates (the top four were elected), though he got 277 of the 300 votes cast in the New Salem precinct.[46]

Lincoln served as New Salem's postmaster and later as county surveyor, after more dedicated self education.[47] In 1834, he won election to the state legislature; though he ran as a Whig, many Democrats favored him over a more powerful Whig opponent.[48] He then decided to become a lawyer and began teaching himself law by reading Blackstone's Commentaries on the Laws of England and other law books. Of his learning method, Lincoln stated: "I studied with nobody."[49] Admitted to the bar in 1836,[50][51] he moved to Springfield, Illinois, and began to practice law under John T. Stuart, Mary Todd's cousin.[52] Lincoln became an able and successful lawyer with a reputation as a formidable adversary during cross-examinations and closing arguments. In 1841, he partnered with Stephen Logan until 1844, when he began his practice with William Herndon, whom Lincoln thought "a studious young man."[53] He served four successive terms in the Illinois House of Representatives as a Whig representative from Sangamon County.[54]

In the 1835–1836 legislative session, he voted to expand suffrage to white males, whether landowners or not.[55][56] He was known for his "free soil" stance of opposing both slavery and abolitionism. He first articulated this in 1837, saying, "Institution of slavery is founded on both injustice and bad policy, but the promulgation of abolition doctrines tends rather to increase than abate its evils."[57] He closely followed Henry Clay in supporting the American Colonization Society program of making the abolition of slavery practical by helping the freed slaves return to Liberia in Africa.[58]

Early national politics

From the early 1830s, Lincoln was a steadfast Whig and professed to friends in 1861, "I have always been an old-line Henry Clay Whig."[59] The party favored economic modernization in banking, railroads, and internal improvements and espoused urbanization as well as protective tariffs, and Lincoln supported these positions.[60]

In 1846, Lincoln was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives, where he served one two-year term.[61] He was the only Whig in the Illinois delegation, but he showed his party loyalty by participating in almost all votes and making speeches that echoed the party line.[62] Lincoln developed a plan to abolish slavery in the District of Columbia with compensation for the owners and a popular vote on the matter, but he dropped it when he failed to gather sufficient Whig supporters.[63] Lincoln also spoke against the Mexican–American War, which he attributed to President Polk's desire for "military glory—that attractive rainbow, that rises in showers of blood."[64]

Lincoln articulated his opposition to Polk by drafting and introducing his Spot Resolutions. The war had begun with a violent confrontation on territory disputed by Mexico and the U.S., but Polk insisted that Mexican soldiers had "invaded our territory and shed the blood of our fellow-citizens on our own soil."[65][66] Lincoln demanded that Polk show Congress the exact spot on which blood had been shed and prove that the spot was on American soil.[66] Congress never enacted the resolution or even debated it, the national papers ignored it, and it resulted in a loss of political support for Lincoln in his district. One Illinois newspaper derisively nicknamed him "spotty Lincoln".[67][68][69] Lincoln later came to regret some of his statements, especially his attack on the presidential war-making powers.[70]

Realizing Clay was unlikely to win the presidency, Lincoln, who had pledged in 1846 to serve only one term in the House,[71] devoted his efforts in support of General Zachary Taylor for the Whig nomination in the 1848 presidential election.[72] Taylor won and Lincoln hoped to be appointed Commissioner of the General Land Office, but that lucrative patronage job went to an Illinois rival.[73] The administration offered him the consolation prize of secretary or governor of the Oregon Territory. Since the territory was a Democratic stronghold, acceptance would have ended his legal and political career in Illinois, so he declined and resumed his law practice.[74]

Prairie lawyer

Lincoln returned to practicing law in Springfield, handling "every kind of business that could come before a prairie lawyer."[75] Twice a year for sixteen years, ten weeks at a time, he appeared in county seats in the midstate region when the county courts were in session.[76] Lincoln handled many transportation cases in the midst of the nation's western expansion, particularly the conflicts arising from the operation of river barges under the many new railroad bridges. As a riverboat man, Lincoln initially favored those interests but ultimately represented whoever hired him.[77] His reputation grew, and he appeared before the Supreme Court of the United States, arguing a case involving a canal boat that sank after hitting a bridge.[78] In 1849, he received a patent for a flotation device for the movement of boats in shallow water.[79] The idea was never commercialized, but Lincoln is the only president to hold a patent.[80]

In 1851, he represented Alton & Sangamon Railroad in a dispute with one of its shareholders, James A. Barret, who had refused to pay the balance on his pledge to buy shares in the railroad on the grounds that the company had changed its original train route.[81][82] Lincoln successfully argued that the railroad company was not bound by its original charter in existence at the time of Barret's pledge; the charter was amended in the public interest to provide a newer, superior, and less expensive route, and the corporation retained the right to demand Barret's payment. The decision by the Illinois Supreme Court has been cited by numerous other courts in the nation.[81] Lincoln appeared before the Illinois Supreme Court in 175 cases, in 51 as sole counsel, of which 31 were decided in his favor.[83] From 1853 to 1860, another of Lincoln's largest clients was the Illinois Central Railroad.[84]

Lincoln's most notable criminal trial occurred in 1858 when he defended William "Duff" Armstrong, who was on trial for the murder of James Preston Metzker.[85] The case is famous for Lincoln's use of a fact established by judicial notice in order to challenge the credibility of an eyewitness. After an opposing witness testified seeing the crime in the moonlight, Lincoln produced a Farmers' Almanac showing the moon was at a low angle, drastically reducing visibility. Based on this evidence, Armstrong was acquitted.[85] Lincoln rarely raised objections in the courtroom. In 1859, however, in another celebrated case, in which he defended Peachy Harrison, who was accused of stabbing another to death, Lincoln angrily protested the judge's decision to exclude evidence favorable to his client. Instead of holding Lincoln in contempt of court as was expected, the judge, a Democrat, reversed his ruling, allowing the evidence and acquitting Harrison.[85]

Republican politics 1854–1860

Lincoln returned to politics to oppose the pro-slavery Kansas–Nebraska Act (1854); this law repealed the slavery-restricting Missouri Compromise (1820). Senior Senator Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois had incorporated popular sovereignty into the Act. Douglas' provision, which Lincoln opposed, specified the people have the right to determine locally whether to allow slavery in their territory rather than have such a decision imposed on them by the national Congress.[86]

On October 16, 1854, in his "Peoria Speech," Lincoln declared his opposition to slavery, which he repeated en route to the presidency.[87] Speaking in his Kentucky accent, with a very powerful voice,[88] he said the Kansas Act had a "'declared' indifference, but as I must think, a covert 'real' zeal for the spread of slavery. I cannot but hate it. I hate it because of the monstrous injustice of slavery itself. I hate it because it deprives our republican example of its just influence in the world..."[89]

In late 1854, Lincoln ran as a Whig for the U.S. Senate seat from Illinois. At that time, senators were elected by the state legislature.[90] After leading in the first six rounds of voting in the Illinois assembly, his support began to dwindle, and Lincoln instructed his backers to vote for Lyman Trumbull, who defeated opponent Joel Aldrich Matteson.[91] The Whigs had been irreparably split by the Kansas–Nebraska Act. Lincoln said, "I think I am a Whig, but others say there are no Whigs, and that I am an abolitionist, even though I do no more than oppose the extension of slavery." Drawing on remnants of the old Whig party, and on disenchanted Free Soil, Liberty, and Democratic party members, he was instrumental in forging the shape of the new Republican Party.[92] At the Republican convention in 1856, Lincoln placed second in the contest to become the party's candidate for vice president.[93]

In 1857–58, Douglas broke with President Buchanan, leading to a fight for control of the Democratic Party. Some eastern Republicans even favored the reelection of Douglas for the Senate in 1858, since he had led the opposition to the Lecompton Constitution, which would have admitted Kansas as a slave state.[94] In March 1857, the Supreme Court issued its controversial decision in Dred Scott v. Sandford; Chief Justice Roger B. Taney opined that blacks were not citizens, and derived no rights from the Constitution. Lincoln strongly disagreed with the Court's opinion; and this put an end to his past deference to the Court's authority. Lincoln historian David Herbert Donald provides Lincoln's immediate reaction to the decision, showing his evolving position on slavery: "The authors of the Declaration of Independence never intended 'to say all were equal in color, size, intellect, moral developments, or social capacity', but they 'did consider all men created equal—equal in certain inalienable rights, among which are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness'."[95] After the state Republican party convention nominated him for the U.S. Senate in 1858, Lincoln then delivered his House Divided Speech, drawing on Mark's gospel from the Bible: "A house divided against itself cannot stand. I believe this government cannot endure permanently half slave and half free. I do not expect the Union to be dissolved—I do not expect the house to fall—but I do expect it will cease to be divided. It will become all one thing, or all the other."[96][97] The speech created an evocative image of the danger of disunion caused by the slavery debate, and rallied Republicans across the North.[98] The stage was then set for the campaign for statewide election of the Illinois legislature which would, in turn, select Lincoln or Douglas as its U.S. senator.[99]

Lincoln–Douglas debates and Cooper Union speech

The 1858 campaign featured the seven Lincoln–Douglas debates of 1858, generally considered the most famous political debates in American history.[100] The principals stood in stark contrast both physically and politically. Lincoln warned that "The Slave Power" was threatening the values of republicanism, and accused Douglas of distorting the values of the Founding Fathers that all men are created equal, while Douglas emphasized his Freeport Doctrine, that local settlers were free to choose whether to allow slavery or not, and accused Lincoln of having joined the abolitionists.[101] The debates had an atmosphere of a prize fight and drew crowds in the thousands. Lincoln stated Douglas's popular sovereignty theory was a threat to the nation's morality and that Douglas represented a conspiracy to extend slavery to free states. Douglas said that Lincoln was defying the authority of the U.S. Supreme Court and the Dred Scott decision.[102]

Though the Republican legislative candidates won more popular votes, the Democrats won more seats, and the legislature re-elected Douglas to the Senate. Despite the bitterness of the defeat for Lincoln, his articulation of the issues gave him a national political reputation.[103] In May 1859, Lincoln purchased the Illinois Staats-Anzeiger, a German-language newspaper which was consistently supportive; most of the state's 130,000 German Americans voted Democratic but there was Republican support that a German-language paper could mobilize.[104]

On February 27, 1860, New York party leaders invited Lincoln to give a speech at Cooper Union to a group of powerful Republicans. Lincoln argued that the Founding Fathers had little use for popular sovereignty and had repeatedly sought to restrict slavery. Lincoln insisted the moral foundation of the Republicans required opposition to slavery, and rejected any "groping for some middle ground between the right and the wrong."[105] Despite his inelegant appearance—many in the audience thought him awkward and even ugly[106]—Lincoln demonstrated an intellectual leadership that brought him into the front ranks of the party and into contention for the Republican presidential nomination. Journalist Noah Brooks reported, "No man ever before made such an impression on his first appeal to a New York audience."[107][108] Donald described the speech as a "superb political move for an unannounced candidate, to appear in one rival's (William H. Seward) own state at an event sponsored by the second rival's (Salmon P. Chase) loyalists, while not mentioning either by name during its delivery."[109] In response to an inquiry about his presidential intentions, Lincoln said, "The taste is in my mouth a little."[110]

1860 Presidential nomination and election

On May 9–10, 1860, the Illinois Republican State Convention was held in Decatur.[111] Lincoln's followers organized a campaign team led by David Davis, Norman Judd, Leonard Swett, and Jesse DuBois, and Lincoln received his first endorsement to run for the presidency.[112] Exploiting the embellished legend of his frontier days with his father, Lincoln's supporters adopted the label of "The Rail Candidate."[113] On May 18, at the 1860 Republican National Convention in Chicago, Lincoln became the Republican candidate on the third ballot, beating candidates such as William H. Seward and Salmon P. Chase.[114] Former Democrat Hannibal Hamlin of Maine received the nomination for Vice President to balance the ticket. Lincoln's nomination has been attributed in part to his moderate views on slavery, as well as his support of internal improvements and the protective tariff. In terms of the actual balloting, Pennsylvania put him over the top. (Lincoln made known to Pennsylvania iron interests his support for protective tariffs.) Lincoln's managers had been adroitly focused on this delegation as well as the others, while following Lincoln's strong dictate to "Make no contracts that bind me."[115]

Most Republicans agreed with Lincoln that the North was the aggrieved party, as the Slave Power tightened its grasp on the national government with the Dred Scott decision and the presidency of James Buchanan.[116] Throughout the 1850s, Lincoln doubted the prospects of civil war, and his supporters rejected claims that his election would incite secession.[117] Meanwhile, Douglas was selected as the candidate of the Northern Democrats, with Herschel Vespasian Johnson as the vice-presidential candidate. Delegates from 11 slave states walked out of the Democratic convention, disagreeing with Douglas's position on popular sovereignty, and ultimately selected John C. Breckinridge as their candidate.[118]

As Douglas and the other candidates went through with their campaigns, Lincoln was the only one of them who gave no speeches. Instead, he monitored the campaign closely and relied on the enthusiasm of the Republican Party. The party did the leg work that produced majorities across the North, and produced an abundance of campaign posters, leaflets, and newspaper editorials.[119] There were thousands of Republican speakers who focused first on the party platform, and second on Lincoln's life story, emphasizing his childhood poverty. The goal was to demonstrate the superior power of "free labor," whereby a common farm boy could work his way to the top by his own efforts.[120] The Republican Party's production of campaign literature dwarfed the combined opposition; a Chicago Tribune writer produced a pamphlet that detailed Lincoln's life, and sold one million copies.[121]

Presidency

1860 election and secession

On November 6, 1860, Lincoln was elected the sixteenth president of the United States, beating Democrat Stephen A. Douglas, John C. Breckinridge of the Southern Democrats, and John Bell of the new Constitutional Union Party. He was the first Republican president, winning entirely on the strength of his support in the North; he was not on the ballot in ten states in the South, and won only two of 996 counties in all the Southern states.[122] Lincoln received 1,866,452 votes, Douglas 1,376,957 votes, Breckinridge 849,781 votes, and Bell 588,789 votes. The electoral vote was decisive: Lincoln had 180 and his opponents added together had only 123. Turnout was 82.2 percent, with Lincoln winning the free Northern states. Douglas won Missouri, and split New Jersey with Lincoln.[123] Bell won Virginia, Tennessee, and Kentucky, and Breckinridge won the rest of the South.[124] There were fusion tickets in which all of Lincoln's opponents combined to form one ticket in New York, New Jersey, and Rhode Island, but even if the anti-Lincoln vote had been combined in every state, Lincoln still would have won a majority in the electoral college.[125]

As Lincoln's election became evident, secessionists made clear their intent to leave the Union.[126] On December 20, 1860, South Carolina took the lead; by February 1, 1861, Florida, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas followed.[127][128] Six states then adopted a constitution and declared themselves to be a sovereign nation, the Confederate States of America.[127] The upper South (Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee, Kentucky, Missouri, and Arkansas) listened to, but initially rejected, the secessionist appeal.[129] President Buchanan and President-elect Lincoln refused to recognize the Confederacy.[130] The Confederacy selected Jefferson Davis as their provisional President on February 9, 1861.[131]

There were attempts at compromise, such as the Crittenden Compromise, which would have extended the Missouri Compromise line of 1820,[132] and which some Republicans even supported. Lincoln rejected the idea, saying, "I will suffer death before I consent ... to any concession or compromise which looks like buying the privilege to take possession of this government to which we have a constitutional right."[133] Lincoln, however, did support the Corwin Amendment to the Constitution, which had passed in Congress and protected slavery in those states where it already existed.[134] A few weeks before the war, he went so far as to pen a letter to every governor asking for their support in ratifying the Corwin Amendment as a means to avoid secession.[135]

En route to his inauguration, President-elect Lincoln evaded possible assassins in Baltimore, who were uncovered by Lincoln's head of security, Allan Pinkerton, and on February 23, 1861, arrived in disguise in Washington, D.C., which was placed under substantial military security.[136] Lincoln directed his inaugural speech to the South, saying, "We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies ... The mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battlefield, and patriot grave, to every living heart and hearthstone, all over this broad land, will yet swell the chorus of the Union, when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature."[137] The failure of the Peace Conference of 1861 rendered legislative compromise practically implausible. By March 1861, no leader of the insurrection had proposed rejoining the Union on any terms. Lincoln and nearly every Republican leader agreed a dismantling of the Union could not be tolerated.[138]

War begins

The commander of Fort Sumter, South Carolina sent a request for provisions to Washington, and the execution of Lincoln's order to meet that request was seen by the secessionists as an act of war.[139] On April 12, 1861, Confederate forces fired on Union troops at Fort Sumter, forced them to surrender, and began the war.[140] Historian Allan Nevins argued that the newly inaugurated Lincoln miscalculated in believing that he could preserve the Union,[141] and future general William Tecumseh Sherman, then a civilian, visited Lincoln in the White House during inauguration week and was "sadly disappointed" at Lincoln's seeming failure to realize that "the country was sleeping on a volcano" and that the South was preparing for war.[142] Historian and Lincoln biographer, David Herbert Donald, concluded Lincoln fairly estimated the events leading to the initiation of war. "His repeated efforts to avoid collision in the months between inauguration and the firing on Ft. Sumter showed he adhered to his vow not to be the first to shed fraternal blood. But he also vowed not to surrender the forts. The only resolution of these contradictory positions was for the confederates to fire the first shot; they did just that."[139]

On April 15, Lincoln called on the states to send detachments totaling 75,000 troops[143] to recapture forts, protect the capital, and "preserve the Union," which, in his view, still existed intact despite the actions of the seceding states.[144] These events forced the states to choose sides. Virginia declared its secession, after which the Confederate capital was moved from Montgomery, Alabama to Richmond. North Carolina, Tennessee, and Arkansas also voted for secession over the next two months. Missouri, Kentucky, and Maryland threatened secession,[143] but neither they nor the slave state of Delaware seceded.

Troops headed south towards Washington, D.C., to protect the capital in response to Lincoln's call. On April 19, secessionist mobs in Baltimore that controlled the rail links attacked Union troops traveling to the capital. George William Brown, the Mayor of Baltimore, and other suspect Maryland politicians were arrested and imprisoned as Lincoln suspended the writ of habeas corpus.[145] John Merryman, a leader in the secessionist group in Maryland, petitioned Chief Justice Roger Taney to issue a writ of habeas corpus, saying Lincoln's action of holding Merryman without a hearing was unlawful. Taney issued the writ, thereby ordering Merryman's release, but Lincoln ignored it.[146]

Assuming command for the Union in the war

Lincoln encountered an unprecedented crisis, and he responded as commander-in-chief, using unprecedented powers. He expanded his war powers, and imposed a blockade, disbursed funds before appropriation by Congress, and suspended the writ of habeas corpus, arresting and imprisoning thousands of suspected Confederate sympathizers without warrant.[147]

The war effort was the source of continued disparagement of Lincoln, and dominated his time and attention. From the start, it was clear that bipartisan support would be essential to success in the war effort, and any manner of compromise alienated factions on both sides of the aisle, such as the appointment of Republicans and Democrats to command positions in the Union Army.[148] Copperheads and other opponents of the war criticized Lincoln for refusing to compromise on the slavery issue. Conversely, the Radical Republicans criticized him for moving too slowly in abolishing slavery.[149]

In August 1861, General John C. Frémont created controversy on the Republican side when he issued, without consulting Lincoln, a proclamation of martial law in Missouri. He declared that any citizen found bearing arms could be court-martialed and shot, and that slaves of persons aiding the rebellion would be freed. Charges of negligence in his command of the Department of the West were compounded with allegations of fraud and corruption. Lincoln overruled Frémont's proclamation and he was given another command in November. This decision, in part, prevented the secession of Kentucky while incurring the violence in the North.[150]

The war assumed foreign policy implications in 1861 when James Mason and John Slidell, ministers of the Confederacy to Great Britain and France, boarded the British ship Trent in Havana, Cuba. The U.S. Navy illegally intercepted the Trent on the high seas and seized the two Confederate envoys; Britain protested vehemently while the northern Americans cheered. Lincoln managed to resolve the issue by releasing the two men.[151] Lincoln's foreign policy approach had been initially hands off, due to his inexperience; he left most diplomacy appointments and other foreign policy matters to his Secretary of State, William Seward. Seward's initial reaction to the Trent affair, however, was too bellicose, so Lincoln also turned to Sen. Charles Sumner, the chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee and an expert in British diplomacy.[152]

Despite his lack of expertise in military affairs, Lincoln studied books from the Library of Congress and devoured the telegraphic reports. He kept close tabs on all phases of the military effort, consulted with governors, and selected generals based on their past success. In January 1862, after many complaints of inefficiency and dishonesty in the War Department, Lincoln replaced Simon Cameron with Edwin Stanton as War Secretary, a reputedly successful leader.[153] In terms of war strategy, Lincoln articulated two priorities: to ensure that Washington was well-defended, and to conduct an aggressive war effort that would satisfy the demand in the North for prompt, decisive victory; major Northern newspaper editors expected victory within 90 days.[154] Two days per week, Lincoln would meet with his cabinet in the afternoon, and occasionally his wife would force him to take a carriage ride because she was concerned he was working too hard.[155] Lincoln had learned from General Winfield Scott the need to control strategic points, such as the Mississippi River;[156] and he also knew well the importance of Vicksburg, and understood the necessity of defeating the enemy's army, rather than simply capturing territory.[157]

General McClellan

After the Union defeat at the First Battle of Bull Run and the retirement of the aged Winfield Scott in late 1861, Lincoln appointed Major General George B. McClellan general-in-chief of all the Union armies.[158] McClellan, a young West Point graduate and railroad executive, and Pennsylvania Democrat, took several months to plan and attempt his Peninsula Campaign, longer than Lincoln wanted. The campaign's objective was to capture Richmond by moving the Army of the Potomac by boat to the peninsula and then overland to the Confederate capital. McClellan's repeated delays frustrated Lincoln and Congress, as did his position that no troops were needed to defend Washington. Lincoln insisted on holding some of McClellan's troops in defense of the capital; McClellan, who consistently overestimated the strength of Confederate troops, blamed this decision for the ultimate failure of the Peninsula Campaign.[159]

Lincoln removed McClellan as general-in-chief and appointed Henry Wager Halleck after McClellan's "Harrison's Landing Letter", in which he offered unsolicited political advice to Lincoln urging caution in the war effort.[160] McClellan's letter incensed Radical Republicans, who successfully pressured Lincoln to appoint John Pope, a Republican, as head of the new Army of Virginia. Pope complied with Lincoln's strategic desire to move toward Richmond from the north, thus protecting the capital from attack. However, lacking requested reinforcements from McClellan, now commanding the Army of the Potomac, Pope was soundly defeated at the Second Battle of Bull Run in the summer of 1862, forcing the Army of the Potomac to defend Washington for a second time.[161] The war also expanded with naval operations in 1862 when the CSS Virginia, formerly the USS Merrimack, damaged or destroyed three Union vessels in Norfolk, Virginia before being engaged and damaged by the USS Monitor. Lincoln closely reviewed the dispatches and interrogated naval officers during their clash in the Battle of Hampton Roads.[162]

Despite his dissatisfaction with McClellan's failure to reinforce Pope, Lincoln was desperate, and restored him to command of all forces around Washington, to the dismay of all in his cabinet but Seward.[163] Two days after McClellan's return to command, General Robert E. Lee's forces crossed the Potomac River into Maryland, leading to the Battle of Antietam in September 1862.[164] The ensuing Union victory, one of the bloodiest in American history, enabled Lincoln to announce that he would issue an Emancipation Proclamation in January. He had actually written this some time earlier but could not issue it in the wake of previous military defeats.[165] McClellan then resisted the President's demand that he pursue Lee's retreating and exposed army, while his counterpart General Don Carlos Buell likewise refused orders to move the Army of the Ohio against rebel forces in eastern Tennessee. As a result, Lincoln replaced Buell with William Rosecrans; and, after the 1862 midterm elections, he replaced McClellan with Republican Ambrose Burnside. Both of these replacements were political moderates and prospectively more supportive of the Commander in Chief.[166]

Burnside, against the advice of the president, prematurely launched an offensive across the Rappahannock River and was stunningly defeated by Lee at Fredericksburg in December. Not only had Burnside been defeated on the battlefield, but his soldiers were disgruntled and undisciplined. Desertions during 1863 were in the thousands and they increased after Fredericksburg.[167] Lincoln brought in Joseph Hooker, despite his history of loose talk about a military dictatorship.[168]

The mid-term elections in 1862 brought the Republicans severe losses due to sharp disfavor with the administration over its failure to deliver a speedy end to the war, as well as rising inflation, new high taxes, rumors of corruption, the suspension of habeas corpus, the military draft law, and fears that freed slaves would undermine the labor market. The Emancipation Proclamation announced in September gained votes for the Republicans in the rural areas of New England and the upper Midwest, but it lost votes in the cities and the lower Midwest. While Republicans were discouraged, Democrats were energized and did especially well in Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana, and New York. The Republicans did maintain their majorities in Congress and in the major states, except New York. The Cincinnati Gazette contended that the voters were "depressed by the interminable nature of this war, as so far conducted, and by the rapid exhaustion of the national resources without progress."[169]

In the spring of 1863, Lincoln was optimistic about a group of upcoming battle plans, to the point of thinking the end of the war could be near if a string of victories could be put together; these plans included Hooker's attack on Lee north of Richmond, Rosecrans' on Chattanooga, Grant's on Vicksburg, and a naval assault on Charleston. The Commander in Chief became despondent when none of these plans, at least initially, succeeded.[170]

Hooker was routed by Lee at the Battle of Chancellorsville in May,[171] but continued to command his troops for some weeks. He ignored Lincoln's order to divide his troops, and possibly force Lee to do the same in Harper's Ferry, and tendered his resignation, which was accepted. He was replaced by George Meade, who followed Lee into Pennsylvania for the Gettysburg Campaign, which was a victory for the Union, though Lee's army avoided capture. At the same time, after initial setbacks, Grant laid siege to Vicksburg and the Union navy attained some success in Charleston harbor.[172] After the Battle of Gettysburg, Lincoln clearly understood that his military decisions would be more effectively carried out by conveying his orders through his War Secretary or his general-in-chief on to his generals, who resented his civilian interference with their own plans. Even so, he often would continue to give detailed directions to his generals as Commander in Chief.[173]

Emancipation Proclamation

Lincoln maintained that his power to end slavery was limited by the Constitution. He expected the eventual extinction of slavery would result from preventing its expansion into new U.S. territory. He also sought to persuade the states to accept compensated emancipation in return for their prohibition of slavery (an offer that took effect only in Washington, D.C.). Lincoln believed that curtailing slavery in this manner would economically expunge it, as envisioned by the Founding Fathers.[174] President Lincoln rejected two emancipation attempts by Maj. Gen. John C. Frémont in August 1861 and by Maj. Gen. David Hunter in May 1862 on the grounds that it would upset the border states loyal to the Union.[175]

In July 1862, Congress passed the Second Confiscation Act, which freed the slaves of anyone convicted of aiding the rebellion. Although Lincoln believed it was not within Congress's power to free the slaves, he approved the bill in deference to the legislature. He felt freeing the slaves could only be done by the commander-in-chief using war powers granted by the Constitution. In that month, Lincoln discussed a draft of the Emancipation Proclamation with his cabinet. In it, he stated that "as a fit and necessary military measure, on January 1, 1863, all persons held as a slaves in the Confederate states will thenceforward, and forever, be free."[176]

In a shrewd reply to a denigrating editorial by Horace Greeley of the New York Tribune which urged emancipation as a prerequisite to military success, the President subordinated the goal of ending slavery to the primary goal of preserving the Union.[177] Privately, Lincoln had concluded at this point that the war could not be won without freeing the slaves:

My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union, and is not either to save or to destroy slavery. If I could save the Union without freeing any slave I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone I would also do that. What I do about slavery, and the colored race, I do because I believe it helps to save the Union; and what I forbear, I forbear because I do not believe it would help to save the Union.[177]

The Emancipation Proclamation, issued on September 22, 1862, and put into effect on January 1, 1863, declared free the slaves in ten states not then under Union control, with exemptions specified for areas already under Union control in two states.[178] Once the abolition of slavery in the rebel states became a military objective, as Union armies advanced south, more slaves were liberated until over three million of them in Confederate territory were freed. Lincoln's comment on the signing of the Proclamation was: "I never, in my life, felt more certain that I was doing right, than I do in signing this paper."[179] For some time, Lincoln continued earlier plans to set up colonies for the newly freed slaves. He commented favorably on colonization in the Emancipation Proclamation, but all attempts at such a massive undertaking failed.[180] A few days after the Emancipation was announced, 13 Republican governors met at the War Governors' Conference; they supported the president's Proclamation, but suggested the removal of General George B. McClellan as commander of the Union Army.[181]

Using former slaves in the military was official government policy after the issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation. At first, Lincoln was reluctant to fully implement this program, but by the spring of 1863, he was ready to initiate "a massive recruitment of Negro troops." In a letter to Andrew Johnson, the military governor of Tennessee, encouraging him to lead the way in raising black troops, Lincoln wrote, "The bare sight of 50,000 armed and drilled black soldiers on the banks of the Mississippi would end the rebellion at once."[182] By the end of 1863, at Lincoln's direction, General Lorenzo Thomas had recruited 20 regiments of blacks from the Mississippi Valley.[183] Frederick Douglass once observed of Lincoln: "In his company, I was never reminded of my humble origin, or of my unpopular color."[184]

Gettysburg Address

With the great Union victory at the Battle of Gettysburg in July 1863, and the defeat of the Copperheads in the Ohio election in the fall, Lincoln maintained a strong base of party support and was in a strong position to redefine the war effort, despite the New York City draft riots. The stage was set for his address at the Gettysburg battlefield cemetery on November 19.[185] It became the most quoted speech in American history.[186]

The Gettysburg Address was delivered at the dedication of the Soldiers' National Cemetery in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, on the afternoon of Thursday, November 19, 1863. In 272 words, and three minutes, Lincoln asserted the nation was born, not in 1789, but in 1776, "conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal." He defined the war as an effort dedicated to these principles of liberty and equality. He declared that the deaths of so many brave soldiers would not be in vain, that slavery would end as a result of the losses, and the future of democracy would be assured,[187] that "government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth."[188] He concluded that the Civil War had a profound objective – a new founding of the nation.[189]

General Grant

Meade's failure to capture Lee's army as it retreated from Gettysburg, and the continued passivity of the Army of the Potomac, persuaded Lincoln that a change in command was needed. Lincoln was much impressed by the successes of General Ulysses S. Grant in the west, which made him a strong candidate to head the Union Army. Responding to criticism of Grant after the 1862 Battle of Shiloh, Lincoln had said, "I can't spare this man. He fights."[190] With Grant in command, Lincoln felt the Union Army could relentlessly pursue a series of coordinated offensives in multiple theaters, and have a top commander who agreed on the use of black troops.[191]

Nevertheless, he had some reservation that Grant might be considering a candidacy for President, as McClellan then was. Lincoln arranged for an intermediary to make inquiry into Grant's political intentions, and finding none at that time, decided to promote Grant to commander of the Union Army. He obtained Congress' consent to reinstate for Grant the rarely used full rank of Lieutenant General, once held by George Washington.[192]

Grant waged his bloody Overland Campaign in 1864. This is often characterized as a war of attrition, given high Union losses at battles such as the Battle of the Wilderness and Cold Harbor. Even though they had the advantage of fighting on the defensive, the Confederate forces had "almost as high a percentage of casualties as the Union forces."[193] The high casualty figures of the Union alarmed the North; Grant had lost a third of his army, and Lincoln asked what Grant's plans were, to which the general replied, "I propose to fight it out on this line if it takes all summer."[194]

The Confederacy lacked reinforcements, so Lee's army shrank with every battle, forcing it back to trenches outside Petersburg, Virginia, where Grant began a siege. Lincoln then made an extended visit to Grant's headquarters at City Point, Virginia. This allowed the president to confer in person with Grant and William Tecumseh Sherman about the hostilities, as Sherman coincidentally managed a hasty visit to Grant from his position in North Carolina.[195] Lincoln and the Republican party mobilized support for the draft throughout the North, and replaced his losses.[196]

Lincoln authorized Grant to target the Confederate infrastructure—such as plantations, railroads, and bridges—hoping to destroy the South's morale and weaken its economic ability to continue fighting. Grant's move to Petersburg resulted in the obstruction of three railroads between Richmond and the South. This strategy allowed Generals Sherman and Philip Sheridan to destroy plantations and towns in the Shenandoah Valley. The damage caused by Sherman's March to the Sea through Georgia totaled more than $100 million by the general's own estimate.[197]

Confederate general Jubal Anderson Early began a series of assaults in the North that threatened the Capital. During his raid on Washington, D.C. in 1864, Lincoln was watching the combat from an exposed position; Captain Oliver Wendell Holmes shouted at him, "Get down, you damn fool, before you get shot!"[198] After repeated calls on Grant to defend Washington, Sheridan was appointed and the threat from Early was dispatched.[199]

As Grant continued to wear down Lee's forces, efforts to discuss peace began. Confederate Vice President Stephens led a group to meet with Lincoln, Seward, and others at Hampton Roads. Lincoln refused to allow any negotiation with the Confederacy as a coequal; his sole objective was an agreement to end the fighting and the meetings produced no results.[200] On April 1, Grant successfully outflanked Lee's forces in the Battle of Five Forks and nearly encircled Petersburg, prompting Lee to warn Jefferson Davis to evacuate Richmond. Days later, when that city fell, Lincoln visited the vanquished Confederate capital; as he walked through the city, white Southerners were stone-faced, but freedmen greeted him as a hero. On April 9, Lee surrendered to Grant at Appomattox and the war was effectively over.[201]

1864 re-election

When Grant's spring campaigns turned into bloody stalemates, Lincoln supported Grant's determination to wear down Lee's Confederate army even at the cost of heavy Union casualties. With an election looming, he easily defeated efforts to deny his renomination.[202] At the Convention, the Republican Party selected Andrew Johnson, a War Democrat from the Southern state of Tennessee, as his running mate. To broaden his coalition to include War Democrats as well as Republicans, Lincoln ran under the label of the new Union Party.[203]

The lack of military success wore heavily on the President's re-election prospects, and many Republicans across the country feared that Lincoln would be defeated. Sharing this fear, Lincoln wrote and signed a pledge that, if he should lose the election, he would still defeat the Confederacy before turning over the White House:[204]

This morning, as for some days past, it seems exceedingly probable that this Administration will not be re-elected. Then it will be my duty to so co-operate with the President elect, as to save the Union between the election and the inauguration; as he will have secured his election on such ground that he cannot possibly save it afterward.[205]

Lincoln did not show the pledge to his cabinet, but asked them to sign the sealed envelope.

While the Democratic platform followed the Peace wing of the party and called the war a "failure," their candidate, General George B. McClellan, supported the war and repudiated the platform. Lincoln provided Grant with more troops and mobilized his party to renew its support of Grant in the war effort. Sherman's capture of Atlanta in September and David Farragut's capture of Mobile ended defeatist jitters;[206] the Democratic Party was deeply split, with some leaders and most soldiers openly for Lincoln. By contrast, the National Union Party was united and energized as Lincoln made emancipation the central issue, and state Republican parties stressed the perfidy of the Copperheads.[207] Lincoln was re-elected in a landslide, carrying all but three states, and receiving 78 percent of the Union soldiers' vote.[208]

On March 4, 1865, Lincoln delivered his second inaugural address. In it, he deemed the high casualties on both sides to be God's will. Historian Mark Noll concludes it ranks "among the small handful of semi-sacred texts by which Americans conceive their place in the world."[209] Lincoln said:

Fondly do we hope—fervently do we pray—that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away. Yet, if God wills that it continue, until all the wealth piled by the bond-man's 250 years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash, shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said 3,000 years ago, so still it must be said, "the judgments of the Lord, are true and righteous altogether." With malice toward none; with charity for all; with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in; to bind up the nation's wounds; to care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow, and his orphan—to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace, among ourselves, and with all nations.[210]

Reconstruction

Reconstruction began during the war, as Lincoln and his associates anticipated questions of how to reintegrate the states that had declared secessions, and how to determine the fates of Confederate leaders and freed slaves. Shortly after Lee's surrender, a general had asked Lincoln how the defeated Confederates should be treated, and Lincoln replied, "Let 'em up easy."[211] In keeping with that sentiment, Lincoln led the moderates regarding Reconstruction policy, and was opposed by the Radical Republicans, under Rep. Thaddeus Stevens, Sen. Charles Sumner and Sen. Benjamin Wade, political allies of the president on other issues. Determined to find a course that would reunite the nation and not alienate the South, Lincoln urged that speedy elections under generous terms be held throughout the war. His Amnesty Proclamation of December 8, 1863, offered pardons to those who had not held a Confederate civil office, had not mistreated Union prisoners, and would sign an oath of allegiance.[212]

As Southern states were subdued, critical decisions had to be made as to their leadership while their administrations were re-formed. Of special importance were Tennessee and Arkansas, where Lincoln appointed General Andrew Johnson (the future Vice President and President in 1865) and General Frederick Steele as military governors, respectively. In Louisiana, Lincoln ordered General Nathaniel P. Banks to promote a plan that would restore statehood when 10% of the voters agreed to it. Lincoln's Democratic opponents seized on these appointments to accuse him of using the military to insure his and the Republicans' political aspirations. On the other hand, the Radicals denounced his policy as too lenient, and passed their own plan, the Wade-Davis Bill, in 1864. When Lincoln vetoed the bill, the Radicals retaliated by refusing to seat representatives elected from Louisiana, Arkansas, and Tennessee.[213]

Lincoln's appointments were designed to keep both the moderate and Radical factions in harness. To fill the late Chief Justice Taney's seat on the Supreme Court, he named the choice of the Radicals, Salmon P. Chase, who Lincoln believed would uphold the emancipation and paper money policies.[214]

After implementing the Emancipation Proclamation, which did not apply to every state, Lincoln increased pressure on Congress to outlaw slavery throughout the entire nation, with a constitutional amendment. Lincoln declared that such an amendment would "clinch the whole matter".[215] By December 1863 a proposed constitutional amendment that would outlaw slavery absolutely was brought to Congress for passage. This first attempt at an amendment failed to pass, falling short of a 2/3 majority on June 15, 1864, in the House of Representatives.[216] After a long debate in the House, a second attempt passed Congress on January 13, 1865, and was sent to the state legislatures for ratification.[217]

Redefining the republic and republicanism

The Gettysburg Address defied Lincoln's own prediction that "the world will little note, nor long remember what we say here." The successful reunification of the states had even grammatical consequences for the very name of the country. The term "the United States" has historically been used, sometimes in the plural, and other times in the singular, without any particular grammatical consistency. The Civil War was a significant force in the eventual dominance of the singular usage by the end of the nineteenth century.[218][219]

In recent years, historians have stressed Lincoln's redefinition of republican values. As early as the 1850s, a time when most political rhetoric focused on the sanctity of the Constitution, Lincoln redirected emphasis to the Declaration of Independence as the foundation of American political values—what he called the "sheet anchor" of republicanism.[220] The Declaration's emphasis on freedom and equality for all, rather than the Constitution's tolerance of slavers, shifted the debate. As Diggins concludes regarding the highly influential Cooper Union speech of early 1860, "Lincoln presented Americans a theory of history that offers a profound contribution to the theory and destiny of republicanism itself."[221] His position gained strength because he highlighted the moral basis of republicanism, rather than its legalisms.[222] Nevertheless, in 1861, Lincoln justified the war in terms of legalisms (the Constitution was a contract, and for one party to get out of a contract all the other parties had to agree), and then in terms of the national duty to guarantee a republican form of government in every state.[223]

In March 1861, in his First Inaugural Address, Lincoln explored the nature of democracy. He denounced secession as anarchy, and explained that majority rule had to be balanced by constitutional restraints in the American system. He said "A majority held in restraint by constitutional checks and limitations, and always changing easily with deliberate changes of popular opinions and sentiments, is the only true sovereign of a free people."[224]

Domestic measures

Lincoln adhered to the Whig theory of the presidency, which gave Congress primary responsibility for writing the laws while the Executive enforced them. Lincoln only vetoed four bills passed by Congress; the only important one was the Wade-Davis Bill with its harsh program of Reconstruction.[225] He signed the Homestead Act in 1862, making millions of acres of government-held land in the West available for purchase at very low cost. The Morrill Land-Grant Colleges Act, also signed in 1862, provided government grants for agricultural colleges in each state. The Pacific Railway Acts of 1862 and 1864 granted federal support for the construction of the United States' First Transcontinental Railroad, which was completed in 1869.[226] The passage of the Homestead Act and the Pacific Railway Acts was made possible by the absence of Southern congressmen and senators who had opposed the measures in the 1850s.[227]

Other important legislation involved two measures to raise revenues for the Federal government: tariffs (a policy with long precedent), and a new Federal income tax. In 1861, Lincoln signed the second and third Morrill Tariff, the first having become law under James Buchanan. In 1861, Lincoln signed the Revenue Act of 1861, creating the first U.S. income tax.[228] This created a flat tax of 3 percent on incomes above $800 ($27,129 in current dollars), which was later changed by the Revenue Act of 1862 to a progressive rate structure.[229]

Lincoln also presided over the expansion of the federal government's economic influence in several other areas. The creation of the system of national banks by the National Banking Act provided a strong financial network in the country. It also established a national currency. In 1862, Congress created, with Lincoln's approval, the Department of Agriculture.[230] In 1862, Lincoln sent a senior general, John Pope, to put down the "Sioux Uprising" in Minnesota. Presented with 303 execution warrants for convicted Santee Dakota who were accused of killing innocent farmers, Lincoln conducted his own personal review of each of these warrants, eventually approving 39 for execution (one was later reprieved).[231]

In the wake of Grant's casualties in his campaign against Lee, Lincoln had considered yet another executive call for a military draft, but it was never issued. In response to rumors of one, however, the editors of the New York World and the Journal of Commerce published a false draft proclamation which created an opportunity for the editors and others employed at the publications to corner the gold market. Lincoln's reaction was to send the strongest of messages to the media about such behavior; he ordered the military to seize the two papers. The seizure lasted for two days.[232]

Lincoln is largely responsible for the institution of the Thanksgiving holiday in the United States.[233] Prior to Lincoln's presidency, Thanksgiving, while a regional holiday in New England since the 17th century, had only been proclaimed by the federal government sporadically, and on irregular dates. The last such proclamation was during James Madison's presidency 50 years before. In 1863, Lincoln declared the final Thursday in November of that year to be a day of Thanksgiving.[234] In 1864, Congress enacted unprecedented protection for the area later called Yosemite National Park, and Lincoln signed that act.[235]

Administration, cabinet and Supreme Court appointments 1861–1865

Template:Lincoln cabinet sidebar Lincoln's declared philosophy on court nominations was that "we cannot ask a man what he will do, and if we should, and he should answer us, we should despise him for it. Therefore we must take a man whose opinions are known."[236] Lincoln made five appointments to the United States Supreme Court. Noah Haynes Swayne, nominated January 21, 1862 and appointed January 24, 1862, was chosen as a slavery opposing lawyer, who was also committed to the Union. Samuel Freeman Miller, nominated and appointed on July 16, 1862, supported Lincoln in the 1860 election and was an avowed abolitionist. David Davis, Lincoln's campaign manager in 1860, nominated December 1, 1862 and appointed December 8, 1862, had also served as a judge in Lincoln's Illinois court circuit. Stephen Johnson Field, a previous California Supreme Court justice, was nominated March 6, 1863 and appointed March 10, 1863, and provided geographic balance, as well as political balance to the court as a Democrat. Finally, Lincoln's Treasury Secretary, Salmon P. Chase, was nominated as Chief Justice, and appointed the same day, on December 6, 1864; Chase also brought to the court his experience as U.S. Senator and Governor of Ohio.

States admitted to the Union

West Virginia, admitted to the Union June 20, 1863, contained the former westernmost counties of Virginia that seceded from Virginia after that commonwealth declared its secession from the Union. Nevada was admitted October 31, 1864. Lincoln was not actively involved in the admission of either.[237]

Assassination

In 1864, John Wilkes Booth, a well-known actor and a Confederate spy from Maryland, formulated a plan to kidnap Lincoln in exchange for the release of Confederate prisoners. After attending an April 11 speech in which Lincoln promoted voting rights for blacks, an incensed Booth changed his plans and became determined to assassinate the president.[238] Learning that the President, First Lady, and head Union general Ulysses S. Grant would be attending Ford's Theatre, Booth formulated a plan with co-conspirators to assassinate Vice President Andrew Johnson, Secretary of State William H. Seward and General Grant. Without his main bodyguard, Ward Hill Lamon, Lincoln left to attend the play Our American Cousin on April 14, 1865. Grant along with his wife chose at the last minute to travel to Philadelphia instead of attending the play.[239]

Lincoln's bodyguard, John Parker, left Ford's Theater during intermission to join Lincoln's coachman for drinks in the Star Saloon next door. The now unguarded President sat in his state box in the balcony. Seizing the opportunity, Booth crept up from behind and at about 10:13 pm, aimed at the back of Lincoln's head and fired at point-blank range, mortally wounding the President. Major Henry Rathbone momentarily grappled with Booth but Booth stabbed him and escaped.[241][242]

After being on the run for ten days, Booth was tracked down and found on a farm in Virginia, some 30 miles (48 km) south of Washington D.C. After a brief fight, Booth was killed by Union soldiers on April 26.[243]

An Army surgeon, Doctor Charles Leale, assessed Lincoln's wound as mortal. The dying man was taken across the street to Petersen House. After being in a coma for nine hours, Lincoln died at 7:22 am on April 15. Presbyterian minister Phineas Densmore Gurley, then present, was asked to offer a prayer, after which Secretary of War Stanton saluted and said, "Now he belongs to the ages."[244]

Lincoln's flag-enfolded body was then escorted in the rain to the White House by bareheaded Union officers, while the city's church bells rang. Vice President Johnson was sworn in as President at 10:00 am the day after the assassination. Lincoln lay in state in the East Room, and then in the Capitol Rotunda, before the funeral train bore him to his final resting place in Springfield, Illinois.[245]

Religious and philosophical beliefs

Though he never joined a church, Lincoln was familiar with the Bible and quoted it often. His integration of religion and politics, according to historian Mark Noll, gives Lincoln enduring relevance as one of the nation's greatest public theologians.[246] Historians have debated whether Lincoln's frequent use of religious imagery and language reflected his own personal beliefs or was a device to appeal to his audiences, who were mostly evangelical Protestants.[247]

In the 1850s, Lincoln acknowledged "providence" in a general way, and rarely used the language or imagery of the evangelicals; instead, he regarded the republicanism of the Founding Fathers with an almost religious reverence. However, during the course of the Civil War (and the deaths of his children), Lincoln more frequently acknowledged his own need to depend on God and to seek to fulfill what he perceived to be God's purposes in the war, including the emancipation of slaves.[248] In particular, historians have viewed Lincoln's second inaugural address in terms of the tradition of the Puritan sermon. Lincoln drew on biblical concepts and rhetoric to expose the nation's errors, notably the national sin of slavery, for which the prolonged punishment of the Civil War was God's judgment and punishment. Continuing in the jeremiad tradition, he prayed for an end to the war, called for forgiveness, and expressed hope for divine grace.[249]

Lincoln's theology, according to biographer James G. Randall, resembled Unitarianism. He felt that all human kind would go to heaven and no one would go to hell. He did not believe in the supernatural account of the birth of Christ. He often talked of God, but rarely mentioned Jesus as the Savior—seldom mentioning Jesus at all. Many of his ancestors were Quakers, and he deeply sympathized with their religion. Like many Quakers, he experienced a sense of mysticism, the sense of direct communication with the unseen. He was involved in several séances at the White House, sponsored by his wife, but did not himself become a spiritualist. Lincoln had numerous superstitious beliefs, and sensed that his dreams were omens of the future; throughout his life, he had a strongly fatalistic attitude. He saw himself as an instrument in the hands of God; becoming, in Randall's view, "a man of more intense religiosity than any other President of the United States."[250]

As a child, Lincoln largely rejected organized religion, but the Calvinistic "doctrine of necessity" would remain a factor throughout his life. In 1846, Lincoln described the effect of this doctrine as "that the human mind is impelled to action, or held in rest by some power, over which the mind itself has no control."[251] There were few people who strongly or directly influenced Lincoln's moral and intellectual development and perspectives. There was no teacher, mentor, church leader, community leader, or peer referenced by Lincoln as a singular influence on his intellectual development. Lincoln's personal philosophy was shaped, not by a formal education, but by "an amazingly retentive memory and a passion for reading and learning." Some historians maintain it was Lincoln's reading, rather than his relationships, that were most influential in shaping his personal beliefs.[252][253]

For a time, Lincoln's religious skepticism was fueled by his readings in Enlightenment and economic liberalism.[252] As a member of the Whig party, Lincoln would often use the Declaration of Independence as the expression of these two philosophies.[254] In March 1860, in a speech in New Haven, Connecticut, Lincoln said, regarding slavery, "Whenever this question shall be settled, it must be settled on some philosophical basis. No policy that does not rest upon some philosophical public opinion can be permanently maintained." The philosophical basis for Lincoln's beliefs regarding slavery and other issues of the day require that Lincoln be examined "seriously as a man of ideas."[255]

In a speech given on February 22, 1861 at Independence Hall in Philadelphia, Lincoln said, "I have never had a feeling politically that did not spring from the sentiments embodied in the Declaration of Independence. ...It was not the mere matter of the separation of the Colonies from the motherland; but that sentiment in the Declaration of Independence which gave liberty, not alone to the people of this country, but, I hope, to the world, for all future time.[256]

He found in the Declaration justification for Whig economic policy and opposition to the expansion of slavery and the nativist platform of the Know Nothings. In claiming that all men were created free, Lincoln and the Whigs argued that this freedom required economic advancement, expanded education, territory to grow, and the ability of the nation to absorb the growing immigrant population.[257] He saw the Declaration as more than a political document. To him, as well as to many abolitionists and other antislavery leaders, it established valuable principles which shaped the nation.[258]

As Lincoln matured, especially during his time as president, the idea of a divine will somehow interacting with human affairs increasingly influenced his beliefs and public expressions. On a personal level, the death of his son Willie in February 1862 caused Lincoln to look towards religion for answers and solace.[259] More than any political leader of the day, he fashioned public policy into a mold of religious, perhaps Calvinistic language, that avoided the evangelical, revivalist fervor of the Second Great Awakening.[255] After Willie's death, in the summer or early fall of 1862, Lincoln attempted to put on paper his private thoughts on why, from a divine standpoint, the severity of the war was necessary. He wrote that God "could have either saved or destroyed the Union without a human contest. Yet the contest began. And having begun He could give the final victory to either side any day. Yet the contest proceeds."[260]

In April 1864, in justifying his actions regarding Emancipation, Lincoln wrote, "I claim not to have controlled events, but confess plainly that events have controlled me. Now, at the end of three years struggle the nation's condition is not what either party, or any man devised, or expected. God alone can claim it."[261] In the summer of 1864, when the Union Army was suffering severe casualties, Lincoln drew solace from the Bible. To his friend Joshua Speed, he said, "Take all of this book [the Bible] upon reason that you can, and the balance on faith, and you will live and die a happier and better man." He is also quoted as saying, "this Great Book ... is the best gift God has given to man."[261]

Legacy and memorials

President Lincoln's assassination and death immediately made him a national martyr and myth. To abolitionists, Lincoln was viewed as a champion for human liberty. For generations, Lincoln's name was linked with the Republican party, and synonymous with "freedom and union" during national elections. Many, though not all, in the South considered Lincoln as a man of outstanding ability.[262]

Lincoln is regarded by the public and historians in numerous polls as the greatest president in U.S. history, no where lower than the top three, along with George Washington and Franklin D. Roosevelt. A study published in 2004 found that scholars in the fields of history and politics ranked Lincoln number one, while legal scholars placed him second after Washington.[263]

The ballistic missile submarine Abraham Lincoln and the aircraft carrier Abraham Lincoln were named in his honor.[264] During the Spanish Civil War, the Communist-controlled American faction of the International Brigades named themselves the Abraham Lincoln Brigade.[265] Lincoln has been memorialized in many town, city, and county names,[266] including the capital of Nebraska. Lincoln, Illinois is the only city named for Abraham Lincoln before he became President.[267]