| Croatian: Zajedničko vijeće općina Serbian: Заједничко веће општина | |

| |

| |

Member municipalities in dark green | |

| Abbreviation | ZVO |

|---|---|

| Formation | 1997[2] (due to Erdut Agreement[3] from 1995) |

| Founded at | Vukovar |

| Legal status | Sui generis body formed on the basis of international agreement |

| Purpose | Protection of interests of and rights of Serbs in Eastern Croatia |

| Headquarters | Vukovar[4][5] (regional office in Beli Manastir),[6] Croatia |

| Location | |

Region served | Areas that were under the control of former Eastern Slavonia, Baranja and Western Syrmia |

Membership | Trpinja Erdut Markušica Borovo Jagodnjak Negoslavci Šodolovci |

Official language | Croatian Serbian |

President | Dejan Drakulić[7] |

Secretary | Vinko Lazić[7] |

Main organ | Assembly of the Joint Council of Municipalities |

| Affiliations | Serb National Council |

Budget (2019) | 6,363,531 Croatian kunas[8] (≈860,000 € or ≈950,000 $) |

| Website | Official site TV Production |

The Joint Council of Municipalities in Croatia (Croatian: Zajedničko vijeće općina; Serbian: Заједничко веће општина, romanized: Zajedničko veće opština; abbr. ЗВО, ZVO) is an elected consultative sui generis body which constitutes a form of cultural self-government of Serbs in the eastern Croatian Podunavlje region. The body was established in the initial aftermath of the Croatian War of Independence as a part of the international community's efforts to peacefully settle the conflict in self-proclaimed Eastern Slavonia, Baranya and Western Syrmia. The establishment of the ZVO was one of the explicit provisions of the Erdut Agreement which called upon the United Nations to establish its UNTAES transitional administration.

The Joint Council of Municipalities is not an autonomous administrative unit but a form of cultural autonomy in conformity with relevant Croatian and international law including provisions on local government cooperation. The body and some of its partners are actively pushing for formal legal recognition of ZVO legal personality within the Constructional Act on the Rights of National Minorities with limited success. The proposed change aims to transform its current standing of a free association into a more transparently institutionalized one.

The Joint Council of Municipalities is the founding member of the Serb National Council, national coordination of the Serbs in Croatia.

History[edit]

Background[edit]

During the Croatian War of Independence, a self-proclaimed Serb Autonomous Region SAO Eastern Slavonia, Baranja and Western Syrmia (Eastern Slavonia) was formed along the Danube river in eastern Croatia. SAO Eastern Slavonia, Baranja and Western Syrmia was ethnically cleansed of its non-Serb population and it became part of the self-proclaimed Republic of Serbian Krajina. Within the Republic of Serbian Krajina, Eastern Slavonia was geographically separated from the rest of the entity, preserved certain institutional specificity, and contrary to the rest of Krajina which aligned itself with Republika Srpska, Eastern Slavonia closely aligned its policy with the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. Several Serb military and political officials, including Milošević, were later indicted and in some cases jailed for war crimes committed during and after the conflict in Eastern Slavonia.[9][10]

In the summer of 1995, the Croatian Army took control of the Republic of Serbian Krajina in operations Flash and Storm. The only area of Croatia that remained under Serb control was Eastern Slavonia.[11] Contrary to Krajina, the international community under the United States leadership opposed military solution in Eastern Slavonia and insisted on reintegration based on preservation of the multi-ethnic character of the region. Opposition to a military solution was fueled by the need not to undermine peace efforts in Bosnia and by the humanitarian consequences of the previous two operations. Contrary to Krajina it was expected that the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia would get involved in the conflict in Eastern Croatia potentially leading to further escalation.

After Croatian expression of readiness to intervene militarily, international community efforts and agreement of government in Belgrade local Serb leaders concluded that an agreement is a necessity if they do not want to face the same fate as those in the western parts of Krajina. Meanwhile, Slobodan Milošević and Franjo Tuđman reached a consensus via the Dayton Agreement and on 12 November, the Erdut Agreement ended the war in eastern Croatia.[11] The transitional period was initiated in which the region was reintegrated and directly governed by the United Nations Transitional Administration for Eastern Slavonia, Baranja and Western Sirmium. It was one of the rare cases in which the UN created a protectorate and directly governed the region in question. As an ultimate arbiter in 1997, the UNTAES established predominantly Serb municipalities in the region.[12]

The Erdut agreement guaranteed the Serbs "the highest level of internationally recognized human rights and fundamental freedoms". The Serb community was given the right to "appoint a joint Council of Municipalities" basis on which the body was formed.[11] The council was established in 1997[2][13] The council is one of the founding members of the Serb National Council.[14][15]

History of the Municipal Cooperation in Croatia[edit]

Forms of the state-organized or free municipal organization were known in the Croatian legal system since the time of the Socialist Republic of Croatia within the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. The so-called communities of municipalities were established in the 1974 constitution as first-level administrative units within the republic. From 1986 their self-governing rights were partially limited. The concept of a free municipal association was used by Serb nationalists in Croatia at an early stage of the conflict in the formation of the self-proclaimed Republic of Serbian Krajina. At that time Croatian Serb politician Jovan Rašković argued for the creation of the "integral region" via the establishment of an Association of Municipalities.[16] While the Croatian legal system at the time formally permitted such a form of municipal organization the move was perceived as highly controversial and led to some of the first clashes.[16]

The idea of Serb municipal cooperation reappeared in Eastern Slavonia after the collapse of the Republic of Serbian Krajina. Croatian Government unequivocally refused some of the initial comments and proposals by the United States President Bill Clinton and Ambassador to Croatia Peter Galbraith which included references to the previous Z-4 Plan proposal. This led to the abandonment of the idea of Serb territorial autonomy in the region. This limited future cooperation to inter-municipal forms of cooperation. As any such cooperation might have been perceived as antagonistic and controversial and therefore prevented, the right to establish a joint council of municipalities was explicitly included in the Erdut Agreement. In June 1996 civil society organizations from the region collected 50,000 signatures and on 28 July that same year, they organized demonstrations "For the Just Peace" in Vukovar in which they requested that the region remain one territorial unit with autonomous executive, legislative and judicial powers.[17] In the second half of the year, they asked Transitional Administrator Jacques Paul Klein to keep the region as an Association of Serb Municipalities with executive powers.[17]

In January 1997 expanded session of the regional Executive Council responded to the Croatian Letter of Intent by requesting the creation of a new Serb county and demilitarization of the region.[17] Vojislav Stanimirović told to media from Belgrade that by dividing Serbs into two counties Croatia is trying to dilute political initiatives by the Serb community.[17] This division led to demonstrations which reached their peak on 11 February when 12,000 gathered in Vukovar.[17] Regional Assembly called the referendum on the territorial integrity of the region on 5 March 1997 with the reported turnout of 100,275 voters or 77.40% out of which 99.01% voted for the region to stay undivided within Croatia.[17] UNTAES officials stated that the question asked in the referendum was never one option recognized in the Erdut Agreement.[17] Later on, Vojislav Stanimirović met with Croatian President Franjo Tuđman where Stanimirović stated that "the best option would be a Serb county, but if neither Croatia nor the international community is willing to accept it then the formation of the council of Serb municipalities as planned in Erdut Agreement is the second-best option".[17]

Formation[edit]

Legal basis for the establishment of the Joint Council of Municipalities was provided in the article 12 of the Basic Agreement on the Region of Eastern Slavonia, Baranja and Western Syrmia more commonly known as the Erdut Agreement. Signing of the agreement led to the establishment of the UN led transitional administration in the region. Signing of the agreement was welcomed in the United Nations Security Council Resolution 1023 and the process it initiated was further elaborated in resolutions number 1025, 1037 and 1043.

Towards the end of the transitional administration Croatian Government addressed members of the United Nations Security Council on 13 January 1997 in the Letter of Intent of the Government of the Republic of Croatia in Regard to Finalization of Reintegration of Areas Under the Transitional Administration in local context more commonly known simply as the Letter of Intent. This letter was perceived as a precondition for successful end of the UNTAES mission's mandate and it was signed by then Deputy Prime Minister Ivica Kostović. In it Croatian Government reassured the United Nations Security Council of its intention to organize free and fair local elections in which Serbs and other ethnic communities in the region will be enabled to participate. Article 4 of the letter provided guarantees of proportional Serb participation in political life in Vukovar-Srijem and Osijek-Baranja counties on the basis of the Constitutional Act on the Rights of National Minorities in the Republic of Croatia (the first version of the act adopted in 1991) and the Law on Local Government and Self-Government. Article 4 state that the Serb community in the areas which were under the UNTAES administration will form the Joint Council of Municipalities. The letter state the intention to hold regular meeting between Council's representatives and the President of Croatia each four months.[17]

The founding Charter of the organization was signed by Jure Radić and Miloš Vojnović on 15 July 1997 at the Osijek Airport in the presence of UNTAES Head Jacques Paul Klein.[17] In early August the president of Committee for Civic, Human and Minority Rights, Branko Jurišić, complained to representatives of the European Union Monitoring Mission that the council had not been registered in Zagreb although it had already begun to carry out most of its tasks on the ground.[17] This condition would last until the end of UNTAES mission in 1998.[17]

1997-2013[edit]

31st Plenary Meeting Venice Commission on 20–21 June 1997 adopted its Memorandum on the revision of the Croatian constitutional law of Human Rights and Rights of Minorities in which it recommended "inclusion of elements of the "Letter of intent of the Government of the Republic of Croatia on the peaceful reintegration of the region under transitional administration" in the Revised Constitutional Law".[18] Commission expressed its opinion that revised Constitutional Act should:

set out the framework for the functioning and competence of the "Joint Council of Municipalities" and of the "Council of the Serb Ethnic Community", in accordance with the principles enshrined in the European Charter of local Self-Government, the Framework Convention for the protection of national minorities and Recommendation 1201 (1993) of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe.[18]

Already before the end of the UNTAES mission on 15 January 1998 Croatian Parliament suspended implementation of certain elements of the Constitutional Law on Human Rights and Freedoms and Rights of National and Ethnic Communities or Minorities in the Republic of Croatia related to territorial autonomy of the Autonomous Districts of Knin and Glina. In that respect the law was not fully in force and both the Government and the Venice Commission favored introduction of a new constitutional act whereby the commission recommended that “The rights of national minorities acquired by international agreements before the date this constitutional act takes effect may not be restricted or changed by this Constitutional Act”.[19]

Number of meetings took place between the 1997 Government's decision on establishment of the Joint Council of Municipalities and 1999 registration in which Serb political representatives and members of Croatian Government negotiated the appropriate format of registration of the new entity.[20] Representatives of the council requested that together with its sui-generis nature it should have properties of public-legal entity.[20] Members of Croatian Government were divided whether to support the request for this type of registration or not which blocked the council from participation in some forms of official communication and standards and fixed streamlines of public funding.[20]

Upon the insistence from Serb representatives and the Venice Commission temporary solution was reached until the enactment of the new Constitutional Act on the Rights of National Minorities in the Republic of Croatia in 2003.[20] Based on it Joint Council of Municipalities was registered on the basis of the Government of Croatia formal decision published in official gazette Narodne novine (NN 137/1998, document number 1673) while Serb National Council was registered on the basis of the Law on Non-government Organizations.[20] While the Government of Croatia formal decision defines the Joint Council of Municipalities as a public-legal entity in practice it enjoyed the rights and obligations of non-governmental organization making both organizations just one among many entities instead of legally recognized umbrella organizations in Eastern Slavonia and Croatia respectively.[20]

2010 Parliamentary Amendment Controversy[edit]

In 2010 request to amend legal standing of the entity reached the Parliament of Croatia during the discussion on amendments of the Constitutional Act on the Rights of National Minorities. The original proposal by the Cabinet of Jadranka Kosor to lawmakers included constitutional amendment accepting requests for a changed legal standing with the following provision:

In the area of Vukovar-Syrmia and Osijek-Baranja County and in accordance with the Basic Agreement on Eastern Slavonia, Baranja and Western Sirmium of 12 November 1995. (Erdut Agreement) and the Letter of Intent of the Croatian Government of 13 January 1997., the Joint Council of Municipalities functions as a legal entity.[21]

This proposal by the center right government provoked a heated Parliamentary debate with criticism arising from the centrist liberal Croatian People's Party and followed by the center left MPs. Opponents argued that this proposal will create a kind of local government unit with no parallel in the rest of the country. Milorad Pupovac, MP of the Serb national minority condemned the MPs who were willing to recognize the full independence of Kosovo, while objecting to the autonomy of the local Serbian community.[22] President of the Independent Democratic Serbian Party Vojislav Stanimirović condemned MP Vesna Pusić (then-President of the National Committee for Monitoring Accession Negotiations with EU).[23]

At the ZVO Emergency Council Meeting on the next day then President Dragan Crnogorac condemned statements by Pusić, Ingrid Antičević-Marinović, Josip Leko and Zoran Vinković.[24] He also said; We are not autonomists or separatists, we are legally elected representatives in the local government and members of the Council.[24] Pusić explained her attitude later in the weekly Novosti where she said that she believes that the council should definitely exist but that it does not need constitutional protection.[21] Eventually a compromise was reached that the council would receive preferred status, ensured by an ordinary, not constitutional law.[25]

ZVO is the target of sharp criticism by the Croatian right-wing groups. The Croatian Party of Rights[26] claims that the Council represents a continuation and continuity of Eastern Slavonia, Baranja and Western Syrmia.[27]

Developments since 2013 Croatian EU membership[edit]

Since the 2013 enlargement of the European Union when Croatia joined the Union as its 28th member state the country is faced with the rise of nationalism and intolerance towards minorities.[28] Those developments pushed the Council of Europe to express alarm over the rise of right-wing extremism and neofascism in Croatia.[29] One of the first escalation of increased right-wing sentiments happened in 2013 in Vukovar and the rest of the country with the Anti-Cyrillic protests in Croatia. Joint Council of Municipalities called press conference related to protests which attracted the highest media interest since the end of the UN led reintegration in 1997.[30] At the conference Milorad Pupovac called politicians "not to play with fire" and warned then president of the Croatian Democratic Union Tomislav Karamarko not to interfere into legal field of the interpretation of the Constitutional Act on the Rights of National Minorities in the Republic of Croatia.[30] During the term in office of the Thirteenth Government of the Republic of Croatia between 22 January and 19 October 2016 in which Tomislav Karamarko served as the First Deputy Prime Minister of Croatia state funding for the Joint Council of Municipalities was brought into question.[31] Since the 2016 elections new Prime Minister Andrej Plenković is trying to ease growing political tensions by controlling his own party and leading it towards more moderate course.[32] However, financial and social pressure which the Joint Council of Municipalities faced triggered renewed calls for the change in its legal status. At the Third Grand Assembly of the Serb National Council which took place in the Vatroslav Lisinski Concert Hall in February 2018 and was attended by both the President of Croatia Kolinda Grabar-Kitarović and the President of Serbia Aleksandar Vučić Assembly adopted pronouncement requesting that "institutions of the Serb community, and the Serb National Council and the Joint Council of Municipalities in particular, must be granted the status of minority self-governments".[33]

President of the Republic of Croatia subsequently issued following statement:

In the Republic of Croatia, as a democratic state, everyone has the right to make a request for the fulfillment of rights that he or she considers important, including the Serb National Council, while at the same time everyone else has the right to support or not such a request. To the extent that the fulfillment of these requirements would presuppose amendments to the law or the adoption of new ones, it is the responsibility of the Government of the Republic of Croatia and the relevant bodies of the Croatian Parliament, or the responsibility of the Croatian Parliament.[33]

Structure[edit]

The Council consists of an elected Council Assembly, the Commission for Election and Appointment, the Secretariat, the Office of the President and two Offices of vice-presidents who are the vice-presidents of the two counties.[4] Four committees are an integral part of the council:[34]

- Committee for Civic, Human and Minority Rights

- Committee for Education, Culture and Sport

- Committee for Media, Information and Faith Issues

- Television Production Council

At least once every four months, the Council delegation meets with the President.[35][36] The council has established contacts with the Republic of Serbia.[37][38][39][40] The Council takes part in projects with the EU and the Ministry of Diaspora of Republic of Serbia.[6]

Assembly of the Joint Council of Municipalities[edit]

Assembly of the Joint Council of Municipalities is the representative body for the Serb community in Eastern Slavonia. The Assembly is made up of elected members of the Serbian ethnic community from Eastern Slavonia regardless of their party affiliation. They are elected in parts of Vukovar-Srijem and Osijek-Baranja counties. The election procedure and umber of Councillors is defined in the Statute of the Joint Council of Municipalities.[41]

The municipal councils in which the Serbian community constitute majority, appoints 2 Councillors to the Assembly of the Joint Council of Municipalities.

The statute provides regulation for city councils in which Serb community constitute majority or minority of the population. If Serbs are majority is certain town in Eastern Slavonia they appoint the following number of Councillors:

- cities with population over 30,000- 6 Councillors

- cities with population from 10,000 to 30,000- 4 Councillors

- cities with population up to 10,000- 3 Councillors

The municipal or city councils in which the Serbian community is a minority, appoint half these numbers.

Most members of Council Assembly of Joint Council of Municipalities are members of Independent Democratic Serb Party. In 2017 VI Convocation was formed by 24 delegates, 2 from each of Beli Manastir, Borovo, Markušica, Trpinja, Negoslavaci, Šodolovaci, Jagodnjak and Erdut and 1 from each of Stari Jankovci, Nijemci, Darda, Kneževi Vinogradi, Popovac and Tompojevci.[42] Deputies of Vukovar-Srijem and Osijek-Baranja are appointed members of the Assembly. 2 delegates for Vukovar were not appointed in 2017 and their appointment was postponed for a short period.[42]

| Local unit in Eastern Slavonia | Number of Assembly Councillors |

|---|---|

| Municipality with Serb majority | 2 |

| Municipality with Serb minority | 1 |

| Town with Serb majority (population over 30,000) | 6 |

| Town with Serb minority (population over 30,000) | 3 |

| Town with Serb majority (population 10,000-30,000) | 4 |

| Town with Serb minority (population 10,000-30,000) | 2 |

| Town with Serb majority (up to 10,000) | 3 |

| Town with Serb minority (up to 10,000) | 1 |

Officials[edit]

The incumbent JCM president is Dejan Drakulić from Independent Democratic Serb Party.

Independent Democratic Serb Party Non-party

| Order | Mandate | President | Party | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 2021– | Dejan Drakulić | Independent Democratic Serb Party | |

| 4 | 2017–2021 | Srđan Jeremić | Independent Democratic Serb Party | |

| 3 | 2005–2017 | Dragan Crnogorac | Independent Democratic Serb Party | |

| 2 | 2001–2005 | Jovan Ajduković | Independent Democratic Serb Party | |

| 1 | 1997–2001 | Miloš Vojnović | Independent Democratic Serb Party | |

Symbols[edit]

As an entity of cultural autonomy, the Joint Council of Municipalities defines official national and cultural symbols which are used in eastern Croatia. Decision on the flag, coat of arms and anthem of Serbs in eastern Croatia was made on 14 November 1997.[43] The flag described in the statute of the Joint Council of Municipalities is identical to the flag of Serbs of Croatia subsequently accepted by the Serb National Council.[43] As such it is used around the country on different minority institutions. In addition to the flag, the council's statute defines the usage of the coat of arms of Serbs of Croatia, which is based on the traditional double-headed heraldic Serbian eagle and Serbian cross on a red shield.[43] Behind the shield is a mantle whose internal side is dark blue fringed in the old-gold and with a mitre on top.[43] As the Serb National Council does not define the coat of arms, it is therefore used exclusively in eastern Croatia.[43] The statute of the Joint Council of Municipalities defines Bože pravde as the anthem of Serbian national minority.[43] While the majority of ethnic communities in Croatia use symbols of their mother countries, this is not the case with Serbs in eastern Croatia as they accepted their symbols during the existence of Federal Republic of Yugoslavia and modern symbols of the Republic of Serbia were accepted only in 2006.[43]

International cooperation[edit]

Over the years the council established contact with various international representatives and partners. Council officials had formal meetings with foreign officials, including with former President of Serbia Boris Tadić,[44] US Ambassador in Zagreb,[45] and President of the Government of Vojvodina, Bojan Pajtić.[46] The council is supporting its member municipalities in joint presentation at international events such as trade fairs.

Member municipalities[edit]

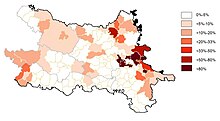

The municipalities part of the council are: Trpinja, Erdut, Markušica, Borovo, Jagodnjak, Negoslavci and Šodolovci.[47] These municipalities are all located in Vukovar-Syrmia and Osijek-Baranja counties. Jagodnjak, Markušica, Šodolovci and Trpinja have a development index of less than 50% of the Croatian average,[48] among the poorest municipalities in Croatia. Borovo, Erdut and Negoslavci have an index of between 50 and 75%.[48] According to 2021 census, these municipalities had a population of 18,925 inhabitants and an area of 587.65 square kilometres, comparable with Isle of Man by territory and with Palau by population.[49] The council's mandate extends to protecting the rights of all 60,500 Serbs who live in territory of the former Eastern Slavonia, Baranja and Western Syrmia.[50] The Joint Council of Municipalities is not a body of territorial autonomy although its mandate is territorially defined.[51]

Any municipality or town in these two counties where Serbs constitute a certain percentage of the population automatically participate in its work. However, no authority of municipalities was formally transferred to the council. The municipalities also co-operate outside the Council in matters that are not within Council jurisdiction, such as joint appearances at fairs.[52][53]

Data by municipalities[edit]

| MUNICIPALITY | Trpinja | Erdut | Markušica | Borovo | Jagodnjak | Negoslavci | Šodolovci | TOTAL |

| Population in 2001 | 6 466[54] | 8 417[55] | 3 053[56] | 5 360[57] | 2 537[58] | 1 466[59] | 1 955[60] | 29 254 |

| Population in 2011 | 5 680[61] | 7 372[61] | 2 576[61] | 5 125[61] | 2 040[61] | 1 472[61] | 1 678[61] | 25 943 |

| Population in 2021 | 4 166[49] | 5 534[49] | 1 800[49] | 3 685[49] | 1 504[49] | 1 012[49] | 1 224[49] | 18 925 |

| Area | 123.87 km2[54] | 158 km2[55] | 73.44 km2[56] | 28.13 km2[57] | 105 km2[58] | 21.21 km2[59] | 78 km2[60] | 587.65 km2 |

| Number of settlements | 7[62] | 4[55] | 5 | 1 | 4[58] | 1 | 7[60] | 29 |

| Number of educational institutions | 8 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 28 |

| Municipality budget 2022 (in EUR) | 2,698,223[63] | 4,292,724[64] | 1,213,454[65] | 3,130,342[66] | 2,340,114[67] | 1,733,383[68] | 1,318,166[69] | 16,726,406 |

Images[edit]

Serb majority municipalities[edit]

-

The Patriarchal Court of the Eparchy of Osječko polje and Baranja

-

Monument in front of the school in Bobota

The community in the rest of the region[edit]

-

Serbian Home building

Education[edit]

Eastern Slavonia, as the area of daily activity of the Joint Council of Municipalities, is characterized by the existence of the regular elementary and secondary school education in minority languages including in Serbian. This type of education is classified in Croatian legal system as the Model A of minority education. Education is conducted either in Croatian or in minority language (Serbian, Hungarian etc.) in accordance with the national curriculum. Education in minority languages involve the so-called national curriculum in which students learn their language for the same number of hours per week as Croatian, while in social science and humanistic subjects such as history, geography, arts and music their national curriculum accounts for one third of the entire studied curriculum, Croatian national content accounts for the second third while European or wider international content covers the last third of the curriculum.

Secondary schools in predominantly Serb settlements are located in Dalj (Dalj High School) and Borovo (part of Vukovar high school). High schools in Vukovar and Beli Manastir provide regular education in Serbian as well. Elementary schools in Serb majority municipalities, some other Serb minority settlements and in towns of Vukovar and Beli Manastir provide regular elementary education in Serbian. The Joint Council of Municipalities actively lobby for transfer of the "founding rights" of regional elementary schools from Vukovar-Srijem and Osijek-Baranja counties to its member municipalities.[70] The Council wants to register those schools in which at the moment education is already provided exclusively in Serbian as public Serbian minority schools, therefore enabling them to officially offer exclusively Model A minority education.[70] This idea is opposed by the Vukovar-Srijem County which insist that Croatian-language education should be the primary choice in all schools, while minority language education should be second regular alternative option available only to members of certain minority group.[70] Joint Council of Municipalities at the same time insist that education in Serbian should be available to all students and not only to ethnic Serbs.[70] As of 2011 95% of students in Serbian-language classes in Vukovar were ethnic Serbs, while 86% of students in Croatian-language classes were ethnic Croats.[71]

In some of those schools minority right to establish separate classes led to effective separation of pupils on national basis which led to some criticism of the practice which critics described as segregation.[72] As this separation is not the result of the majority community exclusion of the minority but of conscious and intentional decision and preference of minority communities this form of separation is not conventionally perceived as segregation in international legal instruments such as the Convention against Discrimination in Education. No institutions of higher education operate in any of majority Serb settlements. The majority of Serb students from the region attend University of Novi Sad, University of Osijek, University of Belgrade, University of Zagreb and University of Banja Luka. Local Polytechnic Lavoslav Ružička Vukovar does not provide education in Serbian despite being active in the region of Eastern Slavonia.

The Cultural and Scientific Center "Milutin Milanković" is located in Dalj. Committee for Education, Culture and Sport of Joint Council of Municipalities conducts activities aimed at fostering Serbian and the Serbian Cyrillic alphabet, through preservation of memories of important individuals and events from the past of Serbian state and ethnic group.[73]

-

The Elementary School Trpinja

-

The Elementary School Bobota

-

The Local Elementary School Vera

Culture[edit]

JCM organises multiple cultural events: "Selu u pohode" (English: "Village Revisited"), "Međunarodni festival dečijeg folklora" (English: "International Festival of Child Folklore"), "Horsko duhovno veče" (English: "Choir Spiritual Night") and "Izložba likovnog stvaralaštva" (English: "The exhibition of fine art"). Veteran Football League brings together 10 soccer clubs. The Council sponsors Chess Leagues and a Shooting League. The council also publishes a monthly magazine Izvor[4] (English: "Source") and, in co-operation with Radio Television of Serbia and Radio Television of Vojvodina, it broadcasts twice per month a TV show named "Hronika Slavonije, Baranje i zapadnog Srema" (English: "Chronicle of Slavonia, Baranja and Western Syrmia").[34] New media project named srbi.hr[74] started in April 2018 in a form of web portal. JCm collaborates with local minority media such as Radio Borovo, and has a 25% stake in Radio Dunav in Vukovar[75] and educational institutions such as Serbian Orthodox Secondary School.[76]

On 23 May 2011, JCM celebrated the "Day of the Joint Council of Municipalities". The day began by laying flowers on the grave of the first President of Council, Miloš Vojnović at a New cemetery in Vukovar.[77][78] After that, in the hotel "Lav", a ceremony took place. Council President Dragan Crnogorac stated:

From this important date (i.e. the date of the establishment), Joint Council of Municipalities, as an internationally recognised institution in Croatia, works on preserving of rights and interests of the Serbs, their cultural and educational autonomy, Serbian traditions, customs, language, and the Cyrillic alphabet, but also works on reconstruction, development, and improvement of the entire life of all citizens and because of this it is respected and stable partner of the government and of all entities that are committed to these values.[79]

See also[edit]

- Association of Municipalities of the Republic of Croatia

- Eastern Slavonia, Baranja and Western Srem

- Erdut Agreement

- United Nations Transitional Authority for Eastern Slavonia, Baranja and Western Sirmium

- Serbs of Croatia

- Serb National Council

- List of local government organizations

- Community of Serb Municipalities (in Kosovo)

- Alliance of Serb municipalities (in Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina)

- Eupen-Malmedy

Further reading[edit]

- Minorities in Croatia-report, Minority Rights Group International

- The Thorny Issue of Ethnic Autonomy in Croatia: Serb Leaders and Proposals for Autonomy

References[edit]

- ^ "Status Zajedničkog vijeća općina" (PDF). Retrieved 13 November 2016.

- ^ a b LogIT Internet Usluge – www.logit.hr – tel: 01/3773-062, 01/3773-063, 042/207-507. ".: Radio Borovo :". Radio-borovo.hr.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Peace Agreements Digital Collection-Croatia-The Erdut Agreement, United States Institute of Peace" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 February 2013. Retrieved 27 April 2013.

- ^ a b c Statut Zajedničkog vijeća općina, Vukovar, 2001.

- ^ "Minority Rights Group International : Croatia : Minority Based & Advocacy Organizations". Minorityrights.org. Archived from the original on 19 April 2013. Retrieved 27 April 2013.

- ^ a b "Snv – Vijesti – Zvo U Novu Godinu Učvršćen I Ojačan". Snv.hr. 30 December 2010. Archived from the original on 1 April 2012. Retrieved 3 November 2011.

- ^ a b "ДЕЈАН ДРАКУЛИЋ НОВИ ПРЕДСЕДНИК ЗАЈЕДНИЧКОГ ВЕЋА ОПШТИНА" (in Serbian). Zajedničko veće opština.

- ^ "Skupština ZVO-a: Osigurana finansijska stabilnost i realizacija projekata" (in Serbian). Srbi.hr. 28 December 2018.

- ^ UNTAES: A Success Story in the Former Yugoslavia. "UN Transitional Administration in Eastern Slavonia, Baranja and Western Sirmium". UNTAES.

- ^ Novilist The trial of Goran Hadzic (16 October 2012). "International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia". Novi list.

- ^ a b c Caspersen, Nina (2003). "The Thorny Issue of Ethnic Autonomy in Croatia: Serb Leaders and Proposals for Autonomy" (PDF). London School of Economics. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 March 2011. Retrieved 27 April 2013.

- ^ Kopajtich-Škrlec, Nives (2012). "Područno ustrojstvo u Republici Hrvatskoj, problemi i perspektiva". Sveske Za Javno Pravo (8): 17–26.

- ^ "Erdutski sporazum – Wikizvor" (in Croatian). Hr.wikisource.org.

- ^ "SNV – Srpsko narodno vijeće". Snv.hr. Archived from the original on 21 October 2018. Retrieved 10 October 2011.

- ^ United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. "Minorities in Croatia" (PDF). UNHCR.

- ^ a b Hayball, Harry Jack (2015). Serbia and the Serbian rebellion in Croatia (1990-1991) (Thesis (Ph.D.)). Goldsmiths College. Retrieved 14 September 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Babić, Nikica (2011). "Srpska oblast Istočna Slavonija, Baranja i Zapadni Srijem – od "Oluje" do dovršetka mirne reintegracije hrvatskog Podunavlja (prvi dio)". Scrina Slavonia. 11 (1): 393–454.

- ^ a b Venice Commission. Memorandum on the revision of the Croatian constitutional law of Human Rights and Rights of Minorities (Report). Council of Europe. Retrieved 21 September 2019.

- ^ Venice Commission. Opinion on the Draft Constitutional Law on the Rights of Minorities in Croatia, adopted by the Commission at its 44th Plenary Meeting (Venice, 13-14 October 2000) (Report). Council of Europe. Retrieved 21 September 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f Pupovac, Milorad (20 August 2011). "Usud Srpskog narodnog vijeća" [Destiny of the Serb National Council] (in Serbian). Zagreb: Novosti (Croatia).

- ^ a b "Erdutski sporazum ne mora biti dobar temelj za mirnodopsku državu". Snv.hr.

- ^ "Sabor uz potporu većine izglasovao ustavne promjene – Aktualno – hrvatska – Večernji list". Vecernji.hr.

- ^ Srijeda 24. travnja 2013. 08:07h. "SDSS osudio govor Vesne Pusić u Saboru: To je tragedija – Sabor – Politika – Hrvatska". Dalje.com.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b "Snv – Vijesti – Nismo Autonomaši Niti Separatisti". Snv.hr. 28 June 2010.

- ^ Zlatko Crnčec (24 August 2010). "Srpsko vijeće općina u zakon, ali ne ustavni – Zadarski list". Zadarskilist.hr. Retrieved 21 August 2011.

- ^ "HSP protiv Vijeća općina sa srpskom većinom – tportal.hr /vijesti/". Tportal.hr. 9 February 2010.

- ^ "Braniteljski portal | ...Ne pitaj što domovina može učiniti za tebe, nego što ti možeš učiniti za Domovinu". Braniteljski-portal.hr. Archived from the original on 13 May 2012. Retrieved 21 December 2011.

- ^ Paul Mason (12 September 2016). "Croatia's election is a warning about the return of nationalism to the Balkans". The Guardian. Retrieved 3 November 2019.

- ^ Paul Mason (15 May 2018). "Neo-fascism on the rise in Croatia, Council of Europe finds". Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 3 November 2019.

- ^ a b "Pupovac poručio vlasti i oporbi: Ne igrajte se vatrom". Novi list. 9 October 2013. Retrieved 3 November 2019.

- ^ I. Ćimić (19 February 2018). "Što se krije iza priče o novim zahtjevima hrvatskih Srba?". Index.hr. Retrieved 3 November 2019.

- ^ Boris Pavelić (11 November 2016). "Croatia PM struggles to tame own party". EUobserver. Retrieved 3 November 2019.

- ^ a b "Grabar-Kitarović: Zahtjev Srpskog narodnog vijeća za autonomiju legitiman". Al Jazeera Balkans. 19 February 2018. Retrieved 3 November 2019.

- ^ a b "ZVO/odbori". Zvo.hr. Archived from the original on 4 August 2011. Retrieved 21 August 2011.

- ^ "Pismo hrvatske Vlade Vijeću sigurnosti UN o dovršenju mirne reintegracije" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 April 2012. Retrieved 27 April 2013.

- ^ "Josipović o općem oprostu i srpskoj manjini – tportal.hr /vijesti/". Tportal.hr. 25 March 2011.

- ^ "Info – Tadić meets with Serbs from region". B92. Archived from the original on 11 February 2011. Retrieved 2 November 2011.

- ^ "Vlada Autonomne Pokrajine Vojvodine – Pajtić primio delegaciju Zajedničkog veća opština Vukovar". Vojvodina.gov.rs.

- ^ "Pokrajina finansira srpske studente iz Hrvatske – Radio-televizija Vojvodine". Rtv.rs. 28 November 2011.

- ^ "Ana Tomanova Makanova potpisala ugovore o podršci projektima informisanja u dijaspori". Archived from the original on 30 August 2011. Retrieved 2 November 2011.

- ^ Statut Zajedničkog vijeća općina, članak 14.

- ^ a b "Konstituisan 6. saziv Zajedničkog veća opština l" (in Serbian). Zagreb: Privrednik. 1 August 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g Sekulić, Srđan (15 February 2017). "УПОТРЕБА СИМБОЛА СРПСКЕ НАЦИОНАЛНЕ МАЊИНЕ У РЕПУБЛИЦИ ХРВАТСКОЈ" [The Usage of the Symbols of Serbian National Minority in Croatia] (PDF). Izvor (in Serbian) (161): 10–13. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 14 September 2019.

- ^ "Tadić se sastao s predstavnicima srpske manjine iz regije – Aktualno – svijet – Večernji list". Vecernji.hr.

- ^ "Programs and Events | Embassy of the United States Zagreb, Croatia". Zagreb.usembassy.gov. Archived from the original on 18 February 2013. Retrieved 2 September 2012.

- ^ "Vlada Autonomne Pokrajine Vojvodine". Vojvodina.gov.rs.

- ^ "Novossti, 2011-06, Pokrajine". Novossti.com.

- ^ a b Zadra, odluka_o_razvrstavanju_jedinica_lokalne_i_podrucne_(regionalne)_samouprave_prema_stupnju_razvijenosti Archived 25 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Prvi rezultati popisa 2021" [First results of 2021 census]. Popis '21 (in Croatian and English). 14 January 2022. Archived from the original on 15 January 2022. Retrieved 2 August 2022.

- ^ "Skdprosvjeta, 173". Skdprosvjeta.com.

- ^ "SNV, erdutski-sporazum-ne-mora-biti-dobar-temelj-za-mirnodopsku-drzavu". Snv.hr. Archived from the original on 1 April 2012. Retrieved 10 October 2011.

- ^ doxikus. "Zajednički nastup Općina na Novosadskom sajmu". Slideshare.net.

- ^ "Kratak Izvještaj O Ostvarenoj Prezentaciji Općina Mikroregije, Borovo, Erdut, Jagodnjak, Markušica, Negoslavci I Trpinja". Porc.opcina-erdut.hr.

- ^ a b "vukovarskosrijemska-zupanija, page 75". Vukovarsko-srijemska-zupanija.com. Archived from the original on 10 October 2011. Retrieved 12 October 2011.

- ^ a b c "OBZ, tekst 30". Obz.hr.

- ^ a b "vukovarskosrijemska-zupanija, page 64". Vukovarsko-srijemska-zupanija.com. Archived from the original on 10 October 2011. Retrieved 12 October 2011.

- ^ a b "vukovarskosrijemska-zupanija, page 55". Vukovarsko-srijemska-zupanija.com. Archived from the original on 10 October 2011. Retrieved 12 October 2011.

- ^ a b c "OBZ, tekst 34". Obz.hr.

- ^ a b "vukovarskosrijemska-zupanija, page 65". Vukovarsko-srijemska-zupanija.com. Archived from the original on 10 October 2011. Retrieved 12 October 2011.

- ^ a b c "OBZ, tekst 49". Obz.hr.

- ^ a b c d e f g "DZS, popis, prvi rezultati 2011". Dzs.hr.[permanent dead link]

- ^ http://www.trpinja.hr/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=1&Itemid=3[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Dokumenti - 2022". Općina Trpinja. 2 September 2021. Retrieved 2 August 2022.

- ^ "Proračun općine Erdut za 2022. godinu s projekcijama za 2023. i 2024. godinu" [Budget of the municipality of Erdut for 2022 with projections for 2023 and 2024] (PDF). Općina Erdut (in Croatian). 21 December 2021. Retrieved 2 August 2022.

- ^ "Plan proračuna općine Markušica za 2022.g i financijsku projekciju proračuna za 2023 i 2024.g." [The budget plan of the municipality of Markušica for 2022 and the financial projection of the budget for 2023 and 2024.]. Općina Markušica (in Croatian). 17 December 2022. Retrieved 2 August 2022.

- ^ "Proračun Općine Borovo" [Borovo Municipality budget]. Općina Borovo (in Croatian). 16 December 2021. Retrieved 2 August 2022.

- ^ "Proračun općine Jagodnjak za 2022. godinu" [The budget of the Jagodnjak municipality for the year 2022] (PDF). Općina Jagodnjak (in Croatian). 28 July 2022. Retrieved 2 August 2022.

- ^ "Proračuna općine Negoslavci za 2022. godinu i projekcije proračuna za 2023. i 2024. godinu" [Budget of the municipality of Negoslavci for 2022 and budget projections for 2023 and 2024]. Općina Negoslavci (in Croatian). Retrieved 2 August 2022.

- ^ "Proračun i izvršenje" [Budget and execution]. Općina Šodolovci (in Croatian). 20 December 2021. Retrieved 2 August 2022.

- ^ a b c d Nikola, Milojević (27 March 2019). "Желимо да своје школе региструјемо као што су их регистровали и Чеси, и Италијани и Мађари" [We Want to Register our Schools as the Czechs, Italians and Hungarians Have Done]. Izvor (in Serbian) (214). Vukovar: Joint Council of Municipalities: 5. Retrieved 14 October 2019.

- ^ Dinka Čorkalo Biruški, Dean Ajduković. "Škola kao prostor socijalne integracije djece i mladih u Vukovaru" (PDF). Friedrich Ebert Foundation. Retrieved 24 January 2019.

- ^ Srecko Matic. "Serbs and Croats still segregated in Vukovar's schools". Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 17 January 2019.

- ^ "Zajednicko vece opština Vukovar". Zvo.hr. Archived from the original on 7 October 2011. Retrieved 27 June 2012.

- ^ "srbi.hr – INFORMATIVNI PORTAL". srbi hr (in Serbian). Retrieved 11 October 2018.

- ^ "www.radio-dunav.hr___dobrodošli". Radio-dunav.hr. Archived from the original on 25 June 2006. Retrieved 2 November 2011.

- ^ "Novosti – STRUČNO VIJEĆE UČITELJA SRPSKOG JEZIKA". Archived from the original on 24 April 2012. Retrieved 29 May 2012.

- ^ "Pokrajine". Novossti.com.

- ^ LogIT Internet Usluge – www.logit.hr – tel: 01/3773-062, 01/3773-063, 042/207-507 (24 May 2011). ".: Radio Borovo :". Radio-borovo.hr.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Snv – Vijesti – Međunarodno Priznata Institucija". Snv.hr.