| MAFF | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Aliases | MAFF, U-MAF, hMafF, MAF bZIP transcription factor F | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| External IDs | OMIM: 604877 MGI: 96910 HomoloGene: 7825 GeneCards: MAFF | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Wikidata | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

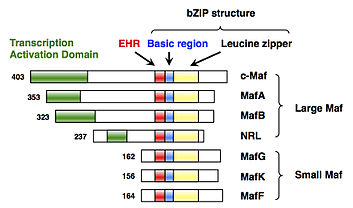

Transcription factor MafF is a bZip Maf transcription factor protein that in humans is encoded by the MAFF gene.[5][6]

MafF is one of the small Maf proteins, which are basic region and leucine zipper (bZIP)-type transcription factors. The HUGO Gene Nomenclature Committee-approved gene name of MAFF is “v-maf avian musculoaponeurotic fibrosarcoma oncogene homolog F”.

Discovery[edit]

MafF was first cloned and identified in chicken in 1993 as a member of the small Maf (sMaf) genes.[5] MAFF has been identified in many vertebrates, including humans.[6] There are three functionally redundant sMaf proteins in vertebrates, MafF, MafG, and MafK.

Structure[edit]

MafF has a bZIP structure that consists of a basic region for DNA binding and a leucine zipper structure for dimer formation.[5] Similar to other sMafs, MafF lacks any canonical transcriptional activation domains.[5]

Expression[edit]

MAFF is broadly but differentially expressed in various tissues. MAFF expression was detected in all 16 tissues examined by the human BodyMap Project, but relatively abundant in adipose, colon, lung, prostate and skeletal muscle tissues.[7] Human MAFF gene is induced by proinflammatory cytokines, interleukin 1 beta and tumor necrosis factor in myometrial cells.[8]

Function[edit]

Because of sequence similarity, no functional differences have been observed among the sMafs in terms of their bZIP structures. sMafs form homodimers by themselves and heterodimers with other specific bZIP transcription factors, such as CNC (cap 'n' collar) proteins [p45 NF-E2 (NFE2), Nrf1 (NFE2L1), Nrf2 (NFE2L2), and Nrf3 (NFE2L3)][9][10][11][12] and Bach proteins (BACH1 and BACH2).[13]

Target genes[edit]

sMafs regulate different target genes depending on their partners. For instance, the p45-NF-E2-sMaf heterodimer regulate genes responsible for platelet production.[9][14][15] Nrf2-sMaf heterodimer regulates a battery of cytoprotective genes, such as antioxidant/xenobiotic metabolizing enzyme genes.[11][16] The Bach1-sMaf heterodimer regulates the heme oxygenase-1 gene.[13] In particular, it has been reported that MafF regulates the oxytocin receptor gene.[17] The contribution of individual sMafs to the transcriptional regulation of their target genes has not yet been well examined.

Disease linkage[edit]

Loss of sMafs results in disease-like phenotypes as summarized in table below. Mice lacking MafF are seemingly healthy under laboratory conditions.[18] However, mice lacking MafG exhibit mild neuronal phenotype and mild thrombocytopenia,[19] mice lacking Mafg and one allele of Mafk (Mafg−/−::Mafk+/−) exhibit progressive neuronal degeneration, thrombocytopenia and cataract,[20][21] and mice lacking MafG and MafK (Mafg−/−::Mafk−/−) exhibit more severe neuronal degeneration and die in the perinatal stage.[22] Mice lacking MafF, MafG and MafK are embryonic lethal, demonstrating that MafF is indispensable for embryonic development.[23] Embryonic fibroblasts that are derived from Maff−/−::Mafg-/−::Mafk−/− mice fail to activate Nrf2-dependent cytoprotective genes in response to stress.[16]

| Genotype | Mouse Phenotype | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Maff | Mafg | Mafk | |

| −/− | No apparent phenotype under laboratory conditions [18] | ||

| −/− | Mild motor ataxia, mild thrombocytopenia [19] | ||

| −/− | +/− | Severe motor ataxia, progressive neuronal degeneration, severe thrombocytopenia, and cataract [20][21] | |

| −/− | −/− | More severe neuronal phenotypes, and perinatal lethal [22] | |

| −/− | +/− | −/− | No severe abnormality [23] (Fertile) |

| −/− | −/− | −/− | Growth retardation, fetal liver hypoplasia, and lethal around embryonic day, 13.5 [23] |

| +/− (heterozygote), −/− (homozygote), blank (wild-type) | |||

In addition, accumulating evidence suggests that as partners of CNC and Bach proteins, sMafs are involved in the onset and progression of various human diseases, including neurodegeneration, arteriosclerosis and cancer.

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000185022 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000042622 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ a b c d Fujiwara KT, Kataoka K, Nishizawa M (Sep 1993). "Two new members of the maf oncogene family, mafK and mafF, encode nuclear b-Zip proteins lacking putative trans-activator domain". Oncogene. 8 (9): 2371–80. PMID 8361754.

- ^ a b "Entrez Gene: MAFF v-maf musculoaponeurotic fibrosarcoma oncogene homolog F (avian)".

- ^ Petryszak R, Burdett T, Fiorelli B, Fonseca NA, Gonzalez-Porta M, Hastings E, Huber W, Jupp S, Keays M, Kryvych N, McMurry J, Marioni JC, Malone J, Megy K, Rustici G, Tang AY, Taubert J, Williams E, Mannion O, Parkinson HE, Brazma A (Jan 2014). "Expression Atlas update--a database of gene and transcript expression from microarray- and sequencing-based functional genomics experiments". Nucleic Acids Research. 42 (Database issue): D926-32. doi:10.1093/nar/gkt1270. PMC 3964963. PMID 24304889.

- ^ Massrieh W, Derjuga A, Doualla-Bell F, Ku CY, Sanborn BM, Blank V (Apr 2006). "Regulation of the MAFF transcription factor by proinflammatory cytokines in myometrial cells". Biology of Reproduction. 74 (4): 699–705. doi:10.1095/biolreprod.105.045450. PMID 16371591. S2CID 11823930.

- ^ a b Igarashi K, Kataoka K, Itoh K, Hayashi N, Nishizawa M, Yamamoto M (Feb 1994). "Regulation of transcription by dimerization of erythroid factor NF-E2 p45 with small Maf proteins". Nature. 367 (6463): 568–72. Bibcode:1994Natur.367..568I. doi:10.1038/367568a0. PMID 8107826. S2CID 4339431.

- ^ Johnsen O, Murphy P, Prydz H, Kolsto AB (Jan 1998). "Interaction of the CNC-bZIP factor TCF11/LCR-F1/Nrf1 with MafG: binding-site selection and regulation of transcription". Nucleic Acids Research. 26 (2): 512–20. doi:10.1093/nar/26.2.512. PMC 147270. PMID 9421508.

- ^ a b Itoh K, Chiba T, Takahashi S, Ishii T, Igarashi K, Katoh Y, Oyake T, Hayashi N, Satoh K, Hatayama I, Yamamoto M, Nabeshima Y (Jul 1997). "An Nrf2/small Maf heterodimer mediates the induction of phase II detoxifying enzyme genes through antioxidant response elements". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 236 (2): 313–22. doi:10.1006/bbrc.1997.6943. PMID 9240432.

- ^ Kobayashi A, Ito E, Toki T, Kogame K, Takahashi S, Igarashi K, Hayashi N, Yamamoto M (Mar 1999). "Molecular cloning and functional characterization of a new Cap'n' collar family transcription factor Nrf3". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 274 (10): 6443–52. doi:10.1074/jbc.274.10.6443. PMID 10037736.

- ^ a b Oyake T, Itoh K, Motohashi H, Hayashi N, Hoshino H, Nishizawa M, Yamamoto M, Igarashi K (Nov 1996). "Bach proteins belong to a novel family of BTB-basic leucine zipper transcription factors that interact with MafK and regulate transcription through the NF-E2 site". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 16 (11): 6083–95. doi:10.1128/mcb.16.11.6083. PMC 231611. PMID 8887638.

- ^ Shavit JA, Motohashi H, Onodera K, Akasaka J, Yamamoto M, Engel JD (Jul 1998). "Impaired megakaryopoiesis and behavioral defects in mafG-null mutant mice". Genes & Development. 12 (14): 2164–74. doi:10.1101/gad.12.14.2164. PMC 317009. PMID 9679061.

- ^ Shivdasani RA, Rosenblatt MF, Zucker-Franklin D, Jackson CW, Hunt P, Saris CJ, Orkin SH (Jun 1995). "Transcription factor NF-E2 is required for platelet formation independent of the actions of thrombopoietin/MGDF in megakaryocyte development". Cell. 81 (5): 695–704. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(95)90531-6. PMID 7774011. S2CID 14195541.

- ^ a b Katsuoka F, Motohashi H, Ishii T, Aburatani H, Engel JD, Yamamoto M (Sep 2005). "Genetic evidence that small maf proteins are essential for the activation of antioxidant response element-dependent genes". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 25 (18): 8044–51. doi:10.1128/MCB.25.18.8044-8051.2005. PMC 1234339. PMID 16135796.

- ^ Kimura T, Ivell R, Rust W, Mizumoto Y, Ogita K, Kusui C, Matsumura Y, Azuma C, Murata Y (Oct 1999). "Molecular cloning of a human MafF homologue, which specifically binds to the oxytocin receptor gene in term myometrium". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 264 (1): 86–92. doi:10.1006/bbrc.1999.1487. PMID 10527846.

- ^ a b Onodera K, Shavit JA, Motohashi H, Katsuoka F, Akasaka JE, Engel JD, Yamamoto M (Jul 1999). "Characterization of the murine mafF gene". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 274 (30): 21162–9. doi:10.1074/jbc.274.30.21162. PMID 10409670.

- ^ a b Shavit JA, Motohashi H, Onodera K, Akasaka J, Yamamoto M, Engel JD (Jul 1998). "Impaired megakaryopoiesis and behavioral defects in mafG-null mutant mice". Genes & Development. 12 (14): 2164–74. doi:10.1101/gad.12.14.2164. PMC 317009. PMID 9679061.

- ^ a b Katsuoka F, Motohashi H, Tamagawa Y, Kure S, Igarashi K, Engel JD, Yamamoto M (Feb 2003). "Small Maf compound mutants display central nervous system neuronal degeneration, aberrant transcription, and Bach protein mislocalization coincident with myoclonus and abnormal startle response". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 23 (4): 1163–74. doi:10.1128/mcb.23.4.1163-1174.2003. PMC 141134. PMID 12556477.

- ^ a b Agrawal SA, Anand D, Siddam AD, Kakrana A, Dash S, Scheiblin DA, Dang CA, Terrell AM, Waters SM, Singh A, Motohashi H, Yamamoto M, Lachke SA (Jul 2015). "Compound mouse mutants of bZIP transcription factors Mafg and Mafk reveal a regulatory network of non-crystallin genes associated with cataract". Human Genetics. 134 (7): 717–35. doi:10.1007/s00439-015-1554-5. PMC 4486474. PMID 25896808.

- ^ a b Onodera K, Shavit JA, Motohashi H, Yamamoto M, Engel JD (Mar 2000). "Perinatal synthetic lethality and hematopoietic defects in compound mafG::mafK mutant mice". The EMBO Journal. 19 (6): 1335–45. doi:10.1093/emboj/19.6.1335. PMC 305674. PMID 10716933.

- ^ a b c Yamazaki H, Katsuoka F, Motohashi H, Engel JD, Yamamoto M (Feb 2012). "Embryonic lethality and fetal liver apoptosis in mice lacking all three small Maf proteins". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 32 (4): 808–16. doi:10.1128/MCB.06543-11. PMC 3272985. PMID 22158967.

Further reading[edit]

- Ye X, Li Y, Huang Q, Yu Y, Yuan H, Wang P, Wan D, Gu J, Huo K, Li YY, Lu H (May 2006). "The novel human gene MIP functions as a co-activator of hMafF". Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 449 (1–2): 87–93. doi:10.1016/j.abb.2006.02.011. PMID 16549056.

- Massrieh W, Derjuga A, Doualla-Bell F, Ku CY, Sanborn BM, Blank V (Apr 2006). "Regulation of the MAFF transcription factor by proinflammatory cytokines in myometrial cells". Biology of Reproduction. 74 (4): 699–705. doi:10.1095/biolreprod.105.045450. PMID 16371591. S2CID 11823930.

- Marini MG, Asunis I, Chan K, Chan JY, Kan YW, Porcu L, Cao A, Moi P (2003). "Cloning MafF by recognition site screening with the NFE2 tandem repeat of HS2: analysis of its role in globin and GCSl genes regulation". Blood Cells, Molecules & Diseases. 29 (2): 145–58. doi:10.1006/bcmd.2002.0550. PMID 12490281.

- Moran JA, Dahl EL, Mulcahy RT (Jan 2002). "Differential induction of mafF, mafG and mafK expression by electrophile-response-element activators". The Biochemical Journal. 361 (Pt 2): 371–7. doi:10.1042/0264-6021:3610371. PMC 1222317. PMID 11772409.

- Kataoka K, Yoshitomo-Nakagawa K, Shioda S, Nishizawa M (Jan 2001). "A set of Hox proteins interact with the Maf oncoprotein to inhibit its DNA binding, transactivation, and transforming activities". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 276 (1): 819–26. doi:10.1074/jbc.M007643200. PMID 11036080.

- Kimura T, Ivell R, Rust W, Mizumoto Y, Ogita K, Kusui C, Matsumura Y, Azuma C, Murata Y (Oct 1999). "Molecular cloning of a human MafF homologue, which specifically binds to the oxytocin receptor gene in term myometrium". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 264 (1): 86–92. doi:10.1006/bbrc.1999.1487. PMID 10527846.

- Johnsen O, Skammelsrud N, Luna L, Nishizawa M, Prydz H, Kolstø AB (Nov 1996). "Small Maf proteins interact with the human transcription factor TCF11/Nrf1/LCR-F1". Nucleic Acids Research. 24 (21): 4289–97. doi:10.1093/nar/24.21.4289. PMC 146217. PMID 8932385.

- Igarashi K, Kataoka K, Itoh K, Hayashi N, Nishizawa M, Yamamoto M (Feb 1994). "Regulation of transcription by dimerization of erythroid factor NF-E2 p45 with small Maf proteins". Nature. 367 (6463): 568–72. Bibcode:1994Natur.367..568I. doi:10.1038/367568a0. PMID 8107826. S2CID 4339431.

External links[edit]

- MAFF+protein,+human at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- FactorBook MafF