Behavioral sleep medicine (BSM) is a field within sleep medicine that encompasses scientific inquiry and clinical treatment of sleep-related disorders, with a focus on the psychological, physiological, behavioral, cognitive, social, and cultural factors that affect sleep, as well as the impact of sleep on those factors.[1][2][3][page needed] The clinical practice of BSM is an evidence-based behavioral health discipline that uses primarily non-pharmacological treatments[3] (that is, treatments that do not involve medications). BSM interventions are typically problem-focused and oriented towards specific sleep complaints, but can be integrated with other medical or mental health treatments (such as medical treatment of sleep apnea, psychotherapy for mood disorders).[4] The primary techniques used in BSM interventions involve education and systematic changes to the behaviors, thoughts, and environmental factors that initiate and maintain sleep-related difficulties.[3][4]

The most common sleep disorders that can benefit from BSM include insomnia,[5] circadian rhythm sleep-wake disorders,[6] nightmare disorder,[7] childhood sleep disorders (for example bedwetting, bedtime difficulties),[8] parasomnias (such as sleepwalking, sleep eating),[9] sleep apnea-associated difficulties (such as difficulty using continuous positive airway pressure),[10] and hypersomnia-associated difficulties (for example daytime fatigue and sleepiness, psychosocial functioning).[11]

Scope[edit]

The clinical practice of behavioral sleep medicine applies behavioral and psychological treatment strategies to sleep disorders.[3][12] BSM specialists provide clinical services including assessment and treatment of sleep disorders and co-occurring psychological symptoms and disorders, often in conjunction with pharmacotherapy and medical devices that may be prescribed by medical professionals.[12]

Most BSM treatments are based on behavioral therapy or cognitive behavioral therapy.[4][page needed] Goals of BSM treatment include directly treating the sleep disorder (for example with cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia[13]), improving adherence to non-behavioral treatments (such as motivational enhancement for CPAP[14]), and improving quality of life for people with chronic sleep disorders (for example, by using cognitive behavioral therapy for hypersomnia[11]).

Training and certification[edit]

Behavioral sleep medicine is a clinical specialty practiced by individuals who are licensed health professionals, including psychologists, counselors, social workers, physicians, nurses, physical therapists, and other healthcare professionals.[15] Licensed BSM practitioners work in a variety of settings, including sleep clinics, hospitals, universities, outpatient mental health clinics, primary care, and private practice.[12] Some scientists conduct behavioral sleep medicine research but are not licensed health providers and do not directly provide clinical treatment.[1]

Training in behavioral sleep medicine varies. Training may be obtained during graduate clinical training, internship/residency, fellowship/postdoctoral training, or through continuing education courses.[16]

The Society of Behavioral Sleep Medicine has established a certification process whereby licensed health professionals who have met certain training requirements can earn the title of Diplomate in Behavioral Sleep Medicine (DBSM). Requirements include graduate course work, specialized clinical training, and passing a written exam.[15] This certification was previously known as Certification in Behavioral Sleep Medicine (CBSM).[citation needed]

Diagnosis[edit]

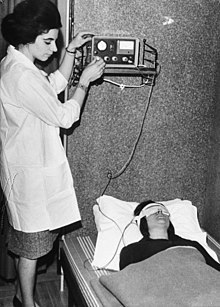

Assessment methods used in behavioral sleep medicine are similar to those used in sleep medicine as a whole. Methods include clinical interview, sleep diaries, standardized questionnaires, polysomnography, actigraphy, and multiple sleep latency test (MSLT).[medical citation needed]

The third edition of the International Classification of Sleep Disorders (ICSD-3)[17][page needed] contains the diagnostic criteria for sleep disorders. Many of these disorders are also described in the diagnostic manual of the American Psychiatric Association, the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5).[18][page needed]

Insomnia[edit]

Insomnia, which is the most common sleep disorder in the population as well as the most common disorder treated by BSM practitioners, is typically evaluated with a clinical interview and two weeks of sleep diaries.[13] The clinical interview examines topics such as sleep patterns, sleep history, psychiatric history, medications, substance use, and relevant medical, developmental, social, occupational, cultural, and environmental factors.[19][20][page needed] For young children, the clinical interview and sleep diaries would be completed primarily by a parent.[8]

Standardized questionnaires may be used to evaluate the severity of the sleep problem or assess for other possible sleep problems. Example questionnaires commonly used with adults include: Insomnia Severity Index,[21] Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index,[22] Epworth Sleepiness Scale,[23] and STOP-Bang.[24] The Brief Infant Sleep Questionnaire[25] is commonly used to assess sleep/wake patterns in infants and small children. Questionnaires commonly used with children and their parents include: Children's Sleep Habits Questionnaire,[26] the Pediatric Sleep Questionnaire,[27] and the Children's Report of Sleep Patterns.[28] Questionnaires commonly used with adolescents include: The Adolescent Sleep Wake Scale[29] and the Adolescent Sleep Hygiene Scale.[29]

Overnight sleep studies (polysomnography) are not necessary or recommended to diagnose insomnia.[13] Polysomnography is used to rule out the presence of other disorders which may require medical treatment, such as sleep apnea, periodic limb movement disorder, and rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder. An MSLT is used to rule out disorders of hypersomnolence such as narcolepsy.[citation needed]

Actigraphy is sometimes used to gain information about sleep timing and assess for possible circadian rhythm disorders.[13]

Other sleep concerns[edit]

Assessment of other sleep concerns follow similar procedures to those for assessing insomnia. By the time individuals are referred to a BSM specialist, they have often already seen a sleep medicine provider and completed any necessary testing such as polysomnography, MSLT, or actigraphy. In that case, the BSM provider conducts a clinical interview and administers questionnaires if needed. Individuals are often asked to track their sleep or sleep-related symptoms such as nightmares or sleepwalking episodes that are the focus of treatment.[medical citation needed]

Management[edit]

BSM practitioners provide evidence-based treatments developed for specific sleep disorders,[3][4] including some that are published in clinical guidelines of organizations such as the American Academy of Sleep Medicine.[7][13][30] BSM interventions are typically brief (between one and eight sessions), structured, and cognitive-behavioral in nature, aiming to provide the education and skills for individuals to become more independent in managing their sleep disorder.[4]

Infants, children, and adolescents[edit]

The most common sleep complaints of parents of infants include requiring a parent or specific condition, like rocking, or bouncing, to fall asleep, and struggling to return to sleep during nighttime awakenings. Among toddlers and preschoolers, nighttime fears or resisting/stalling at bedtime (and therefore delaying sleep onset) are common, as well as bedtime co-sleeping with parents or siblings. In school-aged youth, problems with falling or staying asleep due to poor sleep hygiene are common.[8][page needed]

Insufficient sleep (sleeping under the recommended 8–10 hours) is common in adolescence. The other most common sleep disorders of adolescence include insomnia and delayed sleep-wake phase disorder. High rates of insufficient sleep in adolescence are partially attributed to a mismatch between adolescent biology and school start times.[31] Because adolescents experience a natural shift in their circadian rhythm around puberty (with a preference for later bedtimes and wake times), the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that high schools start no earlier than 8:30am.[32]

Evidence-based treatments for childhood behavioral sleep disorders vary by developmental level, but typically include heavy parental involvement.[33] Interventions generally focus on:[8]

- Stabilizing the timing of the sleep/wake schedule to be consistent on school nights and weekends

- Scheduling enough time in bed to meet clinical guidelines for developmentally appropriate sleep duration

- Promoting healthy bedtime routines that help prepare the body for sleep

- Empowering parents to set limits and rules around expected bedtime behavior

- Promoting independent sleep

- Promoting consistent sleep locations

- Addressing any other barriers to sleep onset (such as nightmares, bedtime fears, fear of the dark, anxiety, depression, pain or discomfort, etc.)

- Addressing family-level barriers to consistently wearing CPAP to treat obstructive sleep apnea and hypoventilation

Treatment with parents of infants emphasizes the implementation of safe sleeping practices in order to reduce the risk of sudden infant death syndrome. The recommends that infants 0–12 months of age sleep:[medical citation needed]

- On their back

- On their own protected sleep surface, such as a crib or other firm sleep surface, and not in the parent's bed, chair, or sofa

- With no heavy blankets, pillows, bumper pads or positioning devices near to them

Adults[edit]

Evidence-based treatments used to treat adult sleep-related disorders include:

- Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I). This is an evidence-based, non-pharmacological treatment for insomnia disorder that uses education and systematic changes to insomnia-related behaviors, thoughts, and environment to change the factors that maintain chronic difficulties with falling asleep, staying asleep, and getting restorative sleep. CBT-I is the first-line treatment for insomnia disorder as recommended by the American College of Physicians[5] and American Academy of Sleep Medicine.[13] It is effective for insomnia disorder that occurs alone or along with other medical or psychiatric symptoms.[34][35]

- Intensive sleep retraining[36]

- Mindfulness-based therapy for insomnia (MBTI)[37][38][page needed]

- Imagery rehearsal therapy (IRT) for nightmare disorder[7]

- Exposure, relaxation, and rescripting therapy (ERRT) for nightmare disorder[39][page needed][7]

- Motivational enhancement therapy for improving adherence to CPAP treatment[40][14]

- Exposure therapy for CPAP claustrophobia[10][4]

- Behavioral therapy for circadian rhythm sleep-wake disorders[6]

- Clinical hypnosis for NREM parasomnias[41][42]

- Cognitive behavioral therapy for hypersomnia[11]

- Sleep extension[43][44]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b Ong, Jason C.; Arand, Donna; Schmitz, Michael; Baron, Kelly; Blackburn, Richard; Grandner, Michael A.; Lichstein, Kenneth L.; Nowakowski, Sara; Teixeira, Celso; Boling, Karlyn; C Dawson, Spencer (November 2018). "A Concept Map of Behavioral Sleep Medicine: Defining the Scope of the Field and Strategic Priorities". Behavioral Sleep Medicine. 16 (6): 523–526. doi:10.1080/15402002.2018.1507672. ISSN 1540-2010. PMID 30118323. S2CID 52033291.

- ^ Stepanski, Edward J. (2003). "Behavioral sleep medicine: a historical perspective". Behavioral Sleep Medicine. 1 (1): 4–21. doi:10.1207/S15402010BSM0101_3. ISSN 1540-2002. PMID 15600134. S2CID 7515944.

- ^ a b c d e [page needed]Treating sleep disorders : principles and practice of behavioral sleep medicine. Perlis, Michael L., Lichstein, Kenneth L. Hoboken, N.J.: Wiley. 2003. ISBN 0-471-44343-3. OCLC 50913755.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ a b c d e f [page needed]Behavioral treatments for sleep disorders : a comprehensive primer of behavioral sleep medicine interventions. Perlis, Michael L., Aloia, Mark, 1967-, Kuhn, Brett R. (1st ed.). Amsterdam: Academic. 2011. ISBN 978-0-12-381522-4. OCLC 690641766.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ a b Qaseem, Amir; Kansagara, Devan; Forciea, Mary Ann; Cooke, Molly; Denberg, Thomas D.; Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians (2016-07-19). "Management of Chronic Insomnia Disorder in Adults: A Clinical Practice Guideline From the American College of Physicians". Annals of Internal Medicine. 165 (2): 125–133. doi:10.7326/M15-2175. ISSN 1539-3704. PMID 27136449. S2CID 207538494.

- ^ a b Auger, R. Robert; Burgess, Helen J.; Emens, Jonathan S.; Deriy, Ludmila V.; Thomas, Sherene M.; Sharkey, Katherine M. (2015-10-15). "Clinical Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Intrinsic Circadian Rhythm Sleep-Wake Disorders: Advanced Sleep-Wake Phase Disorder (ASWPD), Delayed Sleep-Wake Phase Disorder (DSWPD), Non-24-Hour Sleep-Wake Rhythm Disorder (N24SWD), and Irregular Sleep-Wake Rhythm Disorder (ISWRD). An Update for 2015". Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine. 11 (10): 1199–1236. doi:10.5664/jcsm.5100. ISSN 1550-9389. PMC 4582061. PMID 26414986.

- ^ a b c d Morgenthaler, Timothy I.; Auerbach, Sanford; Casey, Kenneth R.; Kristo, David; Maganti, Rama; Ramar, Kannan; Zak, Rochelle; Kartje, Rebecca (15 June 2018). "Position Paper for the Treatment of Nightmare Disorder in Adults: An American Academy of Sleep Medicine Position Paper". Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine. 14 (6): 1041–1055. doi:10.5664/jcsm.7178. ISSN 1550-9397. PMC 5991964. PMID 29852917.

- ^ a b c d [page needed]Mindell, Jodi A. A clinical guide to pediatric sleep : diagnosis and management of sleep problems. Owens, Judith A. (Third ed.). Philadelphia. ISBN 978-1-4698-7554-5. OCLC 913335740.

- ^ Drakatos, Panagis; Leschziner, Guy (November 2019). "Diagnosis and management of nonrapid eye movement-parasomnias". Current Opinion in Pulmonary Medicine. 25 (6): 629–635. doi:10.1097/MCP.0000000000000619. ISSN 1531-6971. PMID 31408014. S2CID 199547831.

- ^ a b Means, Melanie K.; Edinger, Jack D. (2007). "Graded exposure therapy for addressing claustrophobic reactions to continuous positive airway pressure: a case series report". Behavioral Sleep Medicine. 5 (2): 105–116. doi:10.1080/15402000701190572. ISSN 1540-2002. PMID 17441781. S2CID 20567562.

- ^ a b c Ong, Jason C.; Dawson, Spencer C.; Mundt, Jennifer M.; Moore, Cameron (2020-08-17). "Developing a cognitive behavioral therapy for hypersomnia using telehealth: a feasibility study". Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine. 16 (12): 2047–2062. doi:10.5664/jcsm.8750. ISSN 1550-9397. PMC 7848927. PMID 32804069.

- ^ a b c "Behavioral Sleep Medicine Scope of Practice". www.behavioralsleep.org. Retrieved 2020-10-24.

- ^ a b c d e f Schutte-Rodin, Sharon; Broch, Lauren; Buysse, Daniel; Dorsey, Cynthia; Sateia, Michael (2008-10-15). "Clinical Guideline for the Evaluation and Management of Chronic Insomnia in Adults". Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine. 4 (5): 487–504. doi:10.5664/jcsm.27286. ISSN 1550-9389. PMC 2576317. PMID 18853708.

- ^ a b Bakker, Jessie P.; Wang, Rui; Weng, Jia; Aloia, Mark S.; Toth, Claudia; Morrical, Michael G.; Gleason, Kevin J.; Rueschman, Michael; Dorsey, Cynthia; Patel, Sanjay R.; Ware, James H. (August 2016). "Motivational Enhancement for Increasing Adherence to CPAP: A Randomized Controlled Trial". Chest. 150 (2): 337–345. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2016.03.019. ISSN 1931-3543. PMC 4980541. PMID 27018174.

- ^ a b "DBSM Certification Eligibility". bsmcredential.org. Retrieved 2020-10-25.

- ^ "DBSM Certification Guide". bsmcredential.org. Retrieved 2020-10-24.

- ^ [page needed]International classification of sleep disorders. American Academy of Sleep Medicine. (Third ed.). Darien, IL. 2014. ISBN 978-0-9915434-1-0. OCLC 880302262.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ [page needed]Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders : DSM-5. American Psychiatric Association., American Psychiatric Association. DSM-5 Task Force. (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association. 2013. ISBN 978-0-89042-554-1. OCLC 830807378.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Buysse, Daniel J. (2013-02-20). "Insomnia". JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 309 (7): 706–716. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.193. ISSN 0098-7484. PMC 3632369. PMID 23423416.

- ^ [page needed]Manber, Rachel (2015). Treatment plans and interventions for insomnia : a case formulation approach. Carney, Colleen E., 1971-. New York. ISBN 978-1-4625-2009-1. OCLC 904133736.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Morin, Charles M.; Belleville, Geneviève; Bélanger, Lynda; Ivers, Hans (2011-05-01). "The Insomnia Severity Index: psychometric indicators to detect insomnia cases and evaluate treatment response". Sleep. 34 (5): 601–608. doi:10.1093/sleep/34.5.601. ISSN 1550-9109. PMC 3079939. PMID 21532953.

- ^ Buysse, D. J.; Reynolds, C. F.; Monk, T. H.; Berman, S. R.; Kupfer, D. J. (May 1989). "The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research". Psychiatry Research. 28 (2): 193–213. doi:10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. ISSN 0165-1781. PMID 2748771. S2CID 13035531.

- ^ Johns, M. W. (December 1991). "A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the Epworth sleepiness scale". Sleep. 14 (6): 540–545. doi:10.1093/sleep/14.6.540. ISSN 0161-8105. PMID 1798888.

- ^ Chung, Frances; Abdullah, Hairil R.; Liao, Pu (March 2016). "STOP-Bang Questionnaire: A Practical Approach to Screen for Obstructive Sleep Apnea". Chest. 149 (3): 631–638. doi:10.1378/chest.15-0903. ISSN 1931-3543. PMID 26378880.

- ^ Sadeh, Avi (June 2004). "A brief screening questionnaire for infant sleep problems: validation and findings for an Internet sample". Pediatrics. 113 (6): e570–577. doi:10.1542/peds.113.6.e570. ISSN 1098-4275. PMID 15173539.

- ^ Owens, J. A.; Spirito, A.; McGuinn, M. (2000-12-15). "The Children's Sleep Habits Questionnaire (CSHQ): psychometric properties of a survey instrument for school-aged children". Sleep. 23 (8): 1043–1051. doi:10.1093/sleep/23.8.1d. ISSN 0161-8105. PMID 11145319.

- ^ Chervin, null; Hedger, null; Dillon, null; Pituch, null (2000-02-01). "Pediatric sleep questionnaire (PSQ): validity and reliability of scales for sleep-disordered breathing, snoring, sleepiness, and behavioral problems". Sleep Medicine. 1 (1): 21–32. doi:10.1016/s1389-9457(99)00009-x. ISSN 1878-5506. PMID 10733617.

- ^ Meltzer, Lisa J.; Avis, Kristin T.; Biggs, Sarah; Reynolds, Amy C.; Crabtree, Valerie McLaughlin; Bevans, Katherine B. (2013-03-15). "The Children's Report of Sleep Patterns (CRSP): a self-report measure of sleep for school-aged children". Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine. 9 (3): 235–245. doi:10.5664/jcsm.2486. ISSN 1550-9397. PMC 3578690. PMID 23493949.

- ^ a b LeBourgeois, Monique K.; Giannotti, Flavia; Cortesi, Flavia; Wolfson, Amy R.; Harsh, John (January 2005). "The Relationship Between Reported Sleep Quality and Sleep Hygiene in Italian and American Adolescents". Pediatrics. 115 (1 0): 257–265. doi:10.1542/peds.2004-0815H. ISSN 0031-4005. PMC 3928632. PMID 15866860.

- ^ Morgenthaler, Timothy; Kramer, Milton; Alessi, Cathy; Friedman, Leah; Boehlecke, Brian; Brown, Terry; Coleman, Jack; Kapur, Vishesh; Lee-Chiong, Teofilo; Owens, Judith; Pancer, Jeffrey (November 2006). "Practice parameters for the psychological and behavioral treatment of insomnia: an update. An american academy of sleep medicine report". Sleep. 29 (11): 1415–1419. doi:10.1093/sleep/29.11.1415. ISSN 0161-8105. PMID 17162987.

- ^ Crowley, Stephanie J.; Wolfson, Amy R.; Tarokh, Leila; Carskadon, Mary A. (August 2018). "An update on adolescent sleep: New evidence informing the perfect storm model". Journal of Adolescence. 67: 55–65. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2018.06.001. ISSN 1095-9254. PMC 6054480. PMID 29908393.

- ^ Adolescent Sleep Working Group, Committee on Adolescence, Council on School Health (2014-09-01). "School Start Times for Adolescents". Pediatrics. 134 (3): 642–649. doi:10.1542/peds.2014-1697. ISSN 0031-4005. PMC 8194457. PMID 25156998. S2CID 1370122.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Meltzer, Lisa J.; Mindell, Jodi A. (September 2014). "Systematic review and meta-analysis of behavioral interventions for pediatric insomnia". Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 39 (8): 932–948. doi:10.1093/jpepsy/jsu041. ISSN 1465-735X. PMID 24947271.

- ^ Taylor, Daniel J.; Pruiksma, Kristi E. (April 2014). "Cognitive and behavioural therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) in psychiatric populations: a systematic review". International Review of Psychiatry. 26 (2): 205–213. doi:10.3109/09540261.2014.902808. ISSN 1369-1627. PMID 24892895. S2CID 42432521.

- ^ Wu, Jade Q.; Appleman, Erica R.; Salazar, Robert D.; Ong, Jason C. (September 2015). "Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia Comorbid With Psychiatric and Medical Conditions: A Meta-analysis". JAMA Internal Medicine. 175 (9): 1461–1472. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.3006. ISSN 2168-6114. PMID 26147487. S2CID 13480522.

- ^ Lack, Leon; Scott, Hannah; Lovato, Nicole (June 2019). "Intensive Sleep Retraining Treatment of Insomnia". Sleep Medicine Clinics. 14 (2): 245–252. doi:10.1016/j.jsmc.2019.01.005. ISSN 1556-4088. PMID 31029190. S2CID 132279957.

- ^ Ong, Jason C.; Manber, Rachel; Segal, Zindel; Xia, Yinglin; Shapiro, Shauna; Wyatt, James K. (2014-09-01). "A randomized controlled trial of mindfulness meditation for chronic insomnia". Sleep. 37 (9): 1553–1563. doi:10.5665/sleep.4010. ISSN 1550-9109. PMC 4153063. PMID 25142566.

- ^ [page needed]Ong, Jason C. (2017). Mindfulness-based therapy for insomnia. Washington, DC. ISBN 978-1-4338-2242-1. OCLC 957131660.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ [page needed]Davis, Joanne (2009). Treating Post-Trauma Nightmares: A Cognitive Behavioral Approach. Springer. ISBN 9780826102898.

- ^ Aloia, Mark S.; Arnedt, J. Todd; Riggs, Raine L.; Hecht, Jacki; Borrelli, Belinda (2004). "Clinical management of poor adherence to CPAP: motivational enhancement". Behavioral Sleep Medicine. 2 (4): 205–222. doi:10.1207/s15402010bsm0204_3. ISSN 1540-2002. PMID 15600056. S2CID 30892416.

- ^ Drakatos, Panagis; Marples, Lucy; Muza, Rexford; Higgins, Sean; Gildeh, Nadia; Macavei, Raluca; Dongol, Eptehal M.; Nesbitt, Alexander; Rosenzweig, Ivana; Lyons, Elaine; d'Ancona, Grainne (January 2019). "NREM parasomnias: a treatment approach based upon a retrospective case series of 512 patients". Sleep Medicine. 53: 181–188. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2018.03.021. ISSN 1389-9457. PMC 6558250. PMID 29753639.

- ^ Hauri, Peter J.; Silber, Michael H.; Boeve, Bradley F. (2007-06-15). "The Treatment of Parasomnias with Hypnosis: a 5-Year Follow-Up Study". Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine. 3 (4): 369–373. doi:10.5664/jcsm.26858. ISSN 1550-9389. PMC 1978312. PMID 17694725.

- ^ Baron, Kelly Glazer; Duffecy, Jennifer; Reid, Kathryn; Begale, Mark; Caccamo, Lauren (2018-01-10). "Technology-Assisted Behavioral Intervention to Extend Sleep Duration: Development and Design of the Sleep Bunny Mobile App". JMIR Mental Health. 5 (1): e3. doi:10.2196/mental.8634. ISSN 2368-7959. PMC 5784182. PMID 29321122.

- ^ Henst, Rob H. P.; Pienaar, Paula R.; Roden, Laura C.; Rae, Dale E. (December 2019). "The effects of sleep extension on cardiometabolic risk factors: A systematic review". Journal of Sleep Research. 28 (6): e12865. doi:10.1111/jsr.12865. ISSN 1365-2869. PMID 31166059. S2CID 174818171.