The Château of Mariemont (French: Château de Mariemont, Dutch: Kasteel van Mariemont) was a royal residence and hunting lodge for the governors of the Habsburg Netherlands. It was located in Mariemont, in today's village of Morlanwelz, Belgium.

The château's construction started in the 16th century by order of Queen Mary of Hungary and it became a favoured residence in the 17th and 18th centuries. It was rebuilt by Prince Charles Alexander of Lorraine in neoclassical style. It was destroyed by French revolutionary troops in 1794, and today, only ruins remain.

On another location in the park, Nicolas Warocqué, a Belgian industrialist, constructed a new château in the 19th century, which was also destroyed by fire in the 20th century. In its place, a new building was constructed, the Musée royal de Mariemont. The museum and park are open for visitors.

History[edit]

Mary of Hungary[edit]

Construction of the Hunting Pavillion (1546–47)[edit]

The Château of Mariemont owes its name (literally, "Mary-Mount") to its commissioner Queen Mary of Hungary, the sister of Emperor Charles V.[1] After she lost her husband, King Louis II of Hungary, at a fairly young age, in 1531, she was commissioned by her brother to govern the Habsburg Netherlands as governor.[1] To compensate her, in April 1545, he grants her the lifelong benefit of the city and land of Binche.[1] While she had reconstructed the palace in Binche, as a hunting enthusiast, she also ordered a hunting pavilion to be built in the woods of Morlanwelz.[1] The two residences were both designed in 1545–46 by the Mons architect-sculptor Jacques du Broeucq.[1]

Like many artists of the time, Dubroeucq had travelled to Italy. On his way back, he had visited the Châteaux of the Loire Valley. This double influence, Italian and French, can be found in the Renaissance palace of Binche, but much less so in Mariemont.[1] As the location for the hunting lodge, Maria chose the edge of the forest of Morlanwelz, on a hill overlooking the Haine.[1] Dubrœucq drew the plans and supervised the work, which was almost finished in 1547. The building, 19 meters by 7 meters, was surrounded by a wide moat and only accessible via a drawbridge.[1] It was in the form of a two-storey rectangular tower flanked by a turret and capped by a parapet terrace. Mullion windows broke the seriousness of the facades.[1]

The Château of Mariemont, with its rustic and almost medieval appearance, did not pretend to compete with the palace of Binche.[1] Nevertheless, it included a number of luxurious rooms on the ground and first floors.[1] Wood panelling, frescoes and works by renowned artists decorated the apartments of the governor and those of her sister Eleonora, widow of King Francis I of France.[1] Dubrœucq made various models of fireplaces, an alabaster painting for the chapel and, with Luc Lange, thirteen sculptures for the gallery on the first floor. The upper floor, less formal, was intended to be decorated at a later date.[1]

The fire of 1554[edit]

In 1549, Mary organized the "Triumph of Binche" for her brother Charles V and her nephew, the future Philip II. The year before, the aging emperor had decided to have his son recognized as successor by the various principalities that made up his realm.[1] On 22 August 1549, the Imperial procession arrived in Binche. The governor was aware of the importance of the event and organized a grand reception, intended to move the public. Parties, balls and tournaments followed each other for six days. On 28 August, the masquerade ball was in full swing in the great hall of the palace, when gentlemen disguised as "savages" suddenly kidnapped four ladies in medieval dress to Mariemont. The next day, in front of the whole court and with some 20,000 spectators from the surrounding area, a thousand men commanded by the prince of Piedmont and count of Ligne surrounded the palace, stormed it and freed the prisoners. When asked "who kidnapped them this way, they said they did not recognize them at first, but eventually found out they were their husbands".[1]

Shortly after these festivities, the old conflict between Spain and France flared up again.[1] In the spring of 1554, the Imperial army entered Picardy under the command of Adriaan van Croÿ, 1st Count of Roeulx, and ravaged the country up to 70 km from Paris.[1] They destroyed the palace of Folembray, the love nest of Henry II of France and Diana de Poitiers.[1] However, the French troops counterattacked. On 21 July, they raided Binche and Mariemont, whose palaces were set on fire in retaliation. Henry lit the fire himself and had a placard affixed to the ruins: "Queen of folly, remember Folembray!"[1]

But Maria did not hang her head. On her behalf, Dubrœucq started rebuilding the hunting lodge that same year. The governoress retired to Spain in 1556 and died two years later.[1] The château would not be completed until 1560.[1] For about forty years, Mariemont was in a semi-abandoned state, but the palace was maintained.[1] In 1565, the terrace, which was in a very bad state, was replaced by a flat roof better suited to the region's rainy climate.[1]

-

The Château of Mariemont and its surrounding gardens by Jan Brueghel the Elder

-

The Château of Mariemont by Jan Brueghel the Elder

-

Allegory of Spring with the Château of Mariemont in the back by Jan Brueghel the Elder

-

Landscape with the Château of Mariemont by Jan Brueghel the Elder

Albert & Isabella[edit]

In 1598, Philip II abdicated his sovereignty over the Netherlands in favour of his daughter, Isabella, and married Archduke Albert of Austria, who had become governor-general two years earlier.[2] Both archdukes were avid hunters and rediscovered Mariemont: the outer pavilion of Mary of Hungary thus became a royal residence, a status it would retain throughout the Ancien Régime.[2]

As soon as he took over the site, Albert got the restoration work started. In 1600, when the formal demarcation of the site was completed, he decided on the problem of fencing the estate.[2] The old dilapidated wall was replaced by a wooden palisade, interrupted by four monumental stone gates that gave access to the main roads of the park. It would "protect Mariemont's house against thieves" and above all "prevent the entry of foxes such as rabbits and hares".[2]

Gardens[edit]

The derelict gardens were redesigned by the military architect and engineer Pierre Le Poivre, and planted by Loys Patte, the "gardener of the gardens of Their Highness". In 1606, Isabella told Francisco de Sandoval y Rojas, 1st Duke of Lerma, the Spanish Prime Minister, that she had "made every effort to imitate Aranjuez", a royal estate in Spain whose gardens had delighted her childhood.[2] The project was all the easier to carry out because at the time it had been designed by market gardeners from France and especially from the Netherlands.[2]

Contemporary paintings make it possible to reconstruct the arrangement of the gardens of Mariemont in the time of the Archdukes. Flowerbeds, bordered by hedges and in a checkered pattern, lay on a gentle slope at the foot of the château, between the orchards and the grand driveway that led to the Chaussée Brunehaut across the river Haine.[2] The vegetable garden provided food for both the court in Mariemont and Brussels. A painting by Jan Brueghel the Elder, kept in the Museum of Fine Arts of Dijon, perfectly reflects the charm of this "Belgian Touraine", so praised by Isabelle.[2]

First extension (1605–1610)[edit]

From August 1605, work was done to bring the buildings more into line with their function as a royal residence.[2] These works are supervised by Wenceslas Cobergher, a versatile figure: painter, poet, numismatist and architect. In 1610, the grateful archdukes granted him the personal title of "general architect". To begin with, he let the buildings that had been badly damaged by the humidity dry out, repaired roofs and ceilings and replaced the broken windows and glass. Inside, woodwork and carpeting regained their shine.[2]

Because the renovated château was too small to house the court, major expansions were carried out between 1606 and 1610.[2] Next to the path leading to Morlanwelz was a square outbuilding in red brick and covered with slates.[2] A gallery, surmounted by a bell tower, connected it to the château.[2] On the other side, three pavilions with spherical roofs lined an alley that ran parallel to the gardens and ponds.[2] The fountains, which were initially restored, were replaced.[2] Isabelle appreciated Mariemont's water: in 1620 she had "bottled water from the Fontaine Saint-Pierre" brought to Brussels.[2]

Second extension (1618–1620)[edit]

Devout as they were, Albert and Isabella had a chapel built in 1610 outside the park towards La Hestre. Five years later, the chapel and priory of Montaigu was lavishly showered with donations.[2] This establishment is part of the climate of Catholic fervour inspired by the Counter-Reformation, which developed especially from 1609, when the Twelve Years' Truce more or less accepted the secession of the United Provinces (present-day Netherlands).[2] An era of peace and prosperity followed the Civil War, finally allowing the Archdukes to enjoy the delights of Mariemont.[2]

But their increasingly frequent stays emphasize the remoteness of the château, especially since Isabelle was not desperate to one day welcome King Philip III of Spain, her brother.[2] This was the starting point for a new work campaign.[2] In 1618, a building for ladies-in-waiting of the Infante was erected.[2] It closed off the north side of the cour d'honneur (main courtyard).[2] However, most of the extensions related to the main building.[2] Four square towers were erected on the corners of Mary of Hungary's keep.[2] A new balcony was built around the building, to which French doors provided access.[2] A painting by Denis van Alsloot, kept in the Royal Museums of Fine Arts in Brussels, shows the estate as it existed in 1620: the rustic pavilion had become a prestigious château, worthy of a refined court. Embellished in this way, it would not undergo major changes until the 18th century.[2]

-

Archduchess Isabella with the Château of Mariemont in the back by Jan Brueghel the Elder

-

The Château of Mariemont in detail from the painting by Jan Brueghel the Elder

-

View of the Château of Mariemont in its heyday under archdukes Albert and Isabella

-

An architectural model showing the Château of Mariemont in its heyday under archdukes Albert and Isabella

Louis XIV and Maximilian II of Bavaria[edit]

The lively period of the Archdukes ended with Isabella's death in 1633. The governors who succeeded her appeared only briefly in Mariemont. One of them, the 3rd Marquis of Castel Rodrigo, stopped there before laying the foundation stone of a new fortress on the Sambre, Charleroi, on 3 September 1666. Although the splendour of the court was a thing of the past, Mariemont remained animated by the presence of a large number of employees and even a Spanish garrison.

The French years (1668–1678)[edit]

This quiet period ended with a blow when the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle in May 1668 awarded the deanery of Binche to France, albeit with the exception of Mariemont, which the Spaniards regarded as a possession of the Crown. But Louis XIV had not understood it that way: on 27 October, he confiscated the estate and expelled the royal officers and servants who still inhabited the château. Enraged by this affair, the Queen Regent of Spain asked the Apostolic Nuncio and the Ambassador of the Netherlands to intervene with their governments. This did not prevent the Sun King from visiting his new home in 1670 and 1675, nor from including it in the famous series of tapestries called "Draperies of Months or Royal Houses", woven in the Gobelin Manufacture between 1668 and 1683: it illustrates the month of August.

Ten years after the Peace of Aachen, that of Nijmegen returned the deanery of Binche to Spain. The waltz of the governor-generals began again. They stayed there occasionally; one of them, the Marquis of Grana, died there on 19 June 1685. But the deplorable state of government finances made it impossible to keep the château in good condition. Despite the numerous orders, the poorly fenced park was infested with wolves and looters with impunity.

The Bavarian Years (1692–1709)[edit]

Finally, the wind turned with the arrival, in 1692, of the Bavarian Elector Maximilian Emmanuel. This epicurean with opulent flavours, a great hunting enthusiast, appreciated the charm of his Hainaut residence and decided to restore it to its former glory. In a pompous 1699 inscription, he boasted that he "made it (château) as it stands today". However, as far as we know, his work as a builder is limited to the wing leading to the outbuildings, then called the "Bavarian Quarter". But Mariemont owes other things to him: in 1708 he commissioned a composer from the "Stadtkapelle" of Mons to write a pastorale entitled Les Plaisirs de Mariemont and during his reign one of the Walloon regiments was employed by Spain the name "Marimont".

The War of the Spanish Succession quickly turned the area into a battlefield again. From 1709 to 1711, the estate, abandoned by the Elector's court, served as a refuge for the local population.

Maria Elisabeth of Austria[edit]

Third Renaissance (1734–1741)[edit]

In 1714, at the Peace of Rastatt, the Southern Netherlands passed to the Austrian Habsburgs. It would be twenty years before the new governor-general, Archduchess Maria Elisabeth, breathed new life into the estate. From 1734 to 1741, she devoted herself to her favourite pastimes, hunting and fishing.

Unfortunately, these pleasures were spoiled by the "excesses and disturbances found both in the royal house and in the park of Mariemont and its outbuildings". Strict ordinances from 1738 and 1739 tried in vain to discourage looters and poachers. With great piety, Maria Elisabeth had the chapel rebuilt, which had been consecrated in 1739 by the Apostolic Nuncio. The plans for this neoclassical-style building, with a central dome, were the work of court architect Johannes Andreas Anneessens, son of the decapitated craft dean Frans Anneessens.

Spa plans[edit]

But the governor-general attached her name above all to the attempt to create a spa in Mariemont, like the one of which the neighbouring Prince-Bishopric of Liège was so proud: Spa, nicknamed the Café de l'Europe. Apparently blinded by the success of the latter and convinced of the healing virtues of her domain's waters, she intended to exploit it. In fact, the reputation of Mariemont's water was old. Isabella had the water sent to Brussels and Maximillian-Emmanuel to Namur. The abbess of St. Olive used it for a long time and found it very good. It was then just a matter of giving this some scientific authority. Three professors from the University of Leuven, Rega, De Villers and Sassenus, analysed the waters of three wells and published the results first in Latin and then in French for interested physicians. According to their report, the waters of Mariemont were particularly suitable for patients suffering from gastrointestinal disorders, hypochondria, cachexia, amenorrhea and urinary disorders. Each of the sources tested had specific therapeutic qualities.

In order to receive future visitors, Marie-Elisabeth Anneessens had a house built for the main source, the so-called "archducal" source. The building still exists, as does the monumental fountain sculpted by Laurent Delvaux, first rebuilt on site by Raoul Warocqué in 1953 and later moved to the park. Jean François Delval was appointed doctor-director of the spa on 15 May 1741. There was even thought of marketing bottled water. However, the unexpected death of the Archduchess in Mariemont on 26 July of the same year put the company in permanent jeopardy. Although business continued under the impetus of Empress Maria Theresia, the financial difficulties caused by the War of the Austrian Succession hampered the development of the resort. The reputation of Mariemont's waters would remain essentially local until the source dried up in 1773.

-

The Spa house with the archducal source

-

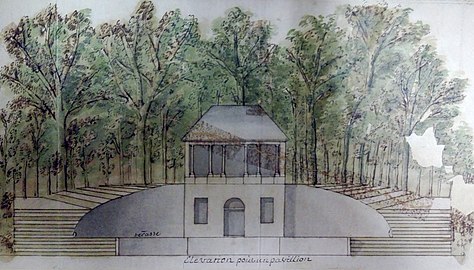

Plan for a pavilion at Mariemont (1743)

Charles of Lorraine[edit]

The pious and stern Marie-Élisabeth was succeeded by a character whose smiling kindness would seduce the populace: Prince Charles Alexander of Lorraine, who settled in the Netherlands in 1749.[3] A great builder and concerned with his own well-being, he multiplied the development projects of his three residences in Brussels, Tervuren and Mariemont.[3] He found the latter in very bad condition.[3] The temporary repairs made during each regal stay were not enough to stop the decline. There were numerous broken windows and broken shutters. Inside, the floors crumbled and damp gnawed at the woodwork.[3] The park was a prey to looters for firewood or coal, the veins of which were exposed here and there.[3] In winter, wolves hunted the remaining game.[3]

A new château (1754–1756)[edit]

Charles of Lorraine opted for a radical solution: demolish the old château and build a new château on its foundations according to the taste of the time.[3] He still had to find an architect and money for that plan.[3] As for the former, Charles complained that no one in all of the Netherlands was able to realize his goal.[3] Finally, he called on a man from Lorraine, Jean-Nicolas Jadot.[3] As a former director-general of the buildings in Vienna, he was appointed intendant of the Royal Houses in the Netherlands in 1753.[3] As for money, the Empress remained deaf to the calls of her brother-in-law, whose expensive tastes she knew too well.[3] Fortunately for him, the States of Hainaut, who wanted to maintain court life in the county, granted him a subsidy of 100,000 florins in the spring of 1754.[3]

Work began on 25 June 1754. The old château of the Archdukes was immediately demolished.[3] Jadot built a neoclassical building in blue stone and white plastered bricks on the site. Due to the sloping terrain, it had two levels to the north, overlooking the courtyard, and three levels to the south, overlooking the gardens.[3] The main facade, on the courtyard side, was set on either side of a portico, the four Ionic columns of which bore a pediment with the coat of arms of Lorraine.[3] The garden facade was decorated with slots on the ground floor and a portico on the first floor.[3] The works went smoothly: less than two years after the start, the new château was under roof.[3]

A grander château (1766–1772)[edit]

As early as 1766, the new court architect Laurent-Benoît Dewez carried out transformations on Jadot's design.[3] From 1769 to 1772, he added two large wings on either side of the courtyard for the stables and kitchens.[3] The fourth side was closed by a rounded grid, carved with pilasters.[3] The entrance portal of the main building, considered too modest, was replaced in 1774 with a new copy of a colossal order.[3] An orangery was built nearby in 1776–77.[3] Two paintings by Jean-Baptiste Simons from 1773 show the château as it appeared then, anticipating the planned works.[3] Only the outbuildings, the "Bavarian quarter", and the chapel of Maria Elisabeth remained of the old château.[3]

The gardens were not forgotten either, as was the park where new paths are drawn and a kiosk constructed in 1771.[3] Later, a triangular lawn was created at the foot of the gardens to open a view of the Haine.[3] Charles would also have liked to have a pond dug there, but due to a lack of money, he was unable to carry out this project.[3] A monumental horseshoe-shaped slope, built by Dewez in 1778, formed the connection between the two terraces.[3] The contractor was Louis Montoyer, son of a game warden from Mariemont and future court architect.[3]

All this work put a painful strain on the prince's treasury.[3] To refloat them, coal was exploited, the presence of which in the subsoil of the park had been known since the Middle Ages. Unfortunately, the operator's incompetence and greed was catastrophic. In 1773, it turned out that the source had dried up due to mining activities. Others would benefit better later on.

Under the reign of Charles of Lorraine, Mariemont has regained the splendour of a joyous court: balls, receptions, theatre and hunting followed one another under the amused eye of a prince who did not blush to mingle in village festivals and entertain people in his house.[3] Charles of Lorraine died on 4 July 1780, the same year as the Empress.[3]

-

Map of Mariemont and its planned gardens in 1763

-

The Château of Mariemont after the reconstruction by Dewez (entrance side) by Jean-Baptiste Simons in 1773

-

Front of the main building in detail

-

The Château of Mariemont after the reconstruction by Dewez (garden side) by Jean-Baptiste Simons in 1773

-

Map of the royal estate of Mariemont in 1780

-

The Château of Mariemont in its heyday (1780)

Destruction[edit]

In response to the French Revolution, Austria, of which the Netherlands were still part, invaded France in the spring of 1792. In the short term this led to the fall of the monarchy and the proclamation of a Republic. In Jemappes, the revolutionary troops won a resounding victory that forced the governors into exile. The French occupation was short-lived, but so was the subsequent restoration. Archduke Charles, Duke of Teschen, brother of Emperor Francis II, did not even have time to go to Mariemont. The French army preceded him and after a meeting with the Austrians on 21 June 1794, set fire to the palace. It was not destroyed, but looting by local residents completed the work of the fire. They stripped the lead from the roofs, knocked down fences, and smashed everything where metal was to be found. As a result, the palace was in ruins.[3]

The park did not escape the destructive fury either. Gangs broke in and began mining coal at random. The neighbouring abbey and its estates suffered the same fate. This violence, in addition to the famine that prevailed at the time, is explained by the hostility of the inhabitants towards the employees of the royal estate and the ladies of the abbey, who enjoyed exorbitant privileges in their eyes. The French government was trying to put an end to vandalism in the "former royal domain", which was then its property. Military patrols roamed the park and the suspects were brought to justice, because "all this is a theft from the Nation."

-

The Château of Mariemont burned down in 1793

-

The ruins of the Château of Mariemont in the 19th century

-

The ruins of the Château of Mariemont in the 19th century

Warocqué family[edit]

At the end of the 18th century, the domain of Mariemont was sold with other national assets confiscated by the French State.[4] At that time the château was one big ruin. The domain was bought by two brothers and industrialists from the region, Isidore and Nicolas Warocqué.[4] Together with three partners, they invested in the estate to mine coal. Thus, in 1802, the Société minière du parc de Mariemont was founded.[4] The company grew very quickly.[4]

In 1805, Nicolas became mayor of Morlanwelz, a position the Warocqués would hold until 1917.[4] In 1829, he bought the forest of Mariemont to make it his private estate and to build a new château. The neoclassical building was designed by the later architect of King Leopold I, Tilman-François Suys.[4]

His son, Abel Warocqué, was the first Warocqué to take up residence in the château.[4] At that time, the park was laid out like an English landscape park, as is still the case today.[4] Leon Warocqué managed the coal mines for only four years, after which his brother Arthur Warocqué took over the management.[4] In this period, there were strikes and riots and the situation in many coal mines was very critical.[4] Mariemont and other Warocqué enterprises were more or less spared from this, thanks to the paternalistic policies and charitable initiatives of the Warocqués towards their workers.[4]

Arthur was the family's first real collector.[4] He also liked to paint himself and collected some well-known paintings.[4] His successor, Georges Warocqué, had almost squandered the family's patrimony and his brother, Raoul Warocqué, had to take over and put things back on track. When Georges died before his time, Raoul became Mariemont's sole heir.[5][4]

Raoul Warocqué[edit]

The last member of the family, Raoul Warocqué, was a great art lover and benefactor, who was imbued with the idea that being rich also meant obligations.[5] With his money, he financed archaeological excavations in the area, supported all kinds of social projects, had libraries and schools built, and helped to alleviate the worst needs of the population during the First World War.[5]

As a great art lover and with the help of specialists such as Franz Cumont and Georges Van der Meylen, Raoul Warocqué put together a special collection in a short time.[5] He enlarged some of his predecessors' collections, such as his mother's collection of lace and the manuscripts of Abel's wife.[5] The Warocqués probably also owned decorative art and a few sets of Tournai porcelain, but it was Raoul who brought together in his château the most complete collection of these objects.[5] Raoul Warocqué was also very interested in the history of his region, which is why a large part of his collection is devoted to the Gallo-Roman period in Hainaut.[5] To increase this, he had excavations carried out in the region (Houdeng-Gœgnies, Fayt-lez-Manage, Chapelle-lez-Herlaimont, Nimy).[5] He also had an early interest in books.[5] When he studied in Paris at the age of 16, he looked for beautiful editions of the classic authors.[5] In addition to his interest in old books, he also subscribed to modern editions.[5]

In the park he had a pavilion built, the "Roman baths", where he could display his Greek and Roman works of art.[5] During his travels in Egypt, he also bought curious Egyptian objects, such as a colossal bust of an Egyptian queen.[5] It is probably through his study of Tournai porcelain that he also discovered Chinese porcelain.[5] Part of his collections is therefore dedicated to the Chinese and Japanese civilizations.[5] Here too he brought back objects from his travels.[5] Raoul also had gazebos built in the park that imitated oriental models.[5] He also ordered and bought sculptures by famous artists of his time, such as The Burghers of Calais by Auguste Rodin and works of art by Jef Lambeaux.[5]

Raoul Warocqué died on 28 May 1917 with no official descendants. He bequeathed his park, his château, his library and his collections to the Belgian State with the aim of turning them into a museum.[5]

Museum[edit]

Richard Schellinck, secretary and librarian to Raoul Warocqué, became the first curator of the Mariemont Museum. Out of loyalty to the former owner, he carried out his last decisions. In 1934, Paul Faider took over the management of the museum and introduced major changes: works of art were restored and a first catalogue was published. His wife, Germaine Faider, succeeded him in 1940 and started the pedagogical service.[5]

On Christmas Eve 1960, a fire broke out in the museum. The collections were largely spared, but the château was destroyed.[4] The ruins were razed to the ground and a contemporary building was built in its place according to plans by architect Roger Bastin.[4] The new Royal Museum of Mariemont was opened on 8 October 1975.[4] Since 1965, the museum has been recognized as a scientific institution, and in 1981, it was transferred to the French Community of Belgium.[4] In 2007, it received the "Prix des Musées" for Wallonia.

-

Ruins of the Château of Mariemont today

-

Ruins of the Château of Mariemont today

-

Ruins of the Château of Mariemont today

See also[edit]

Other residences used by Charles of Lorraine:

- Palace of Charles of Lorraine in Brussels

- Tervuren Castle

- Château Charles in Tervuren

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w Wellens, Robert (1961). "Le domaine de Mariemont au XVIe siècle (1546-1598)". Annales du cercle archéologique de Mons (in French): 79–184.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa Demeester, Joélle (1981). "Le domaine de Mariemont sous Albert et Isabelle (1598-1621)". Annales du cercle archéologique de Mons (in French): 181–282.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah Lemoine-Isabeau, Claire; Jottrand, Mireille (1979). "Mariemont au XVIIIe siècle". Les cahiers de Mariemont (in French). 10: 7–61. doi:10.3406/camar.1979.983.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Donnay, Guy, ed. (1993). Guide du parc et du Musée de Mariemont (in French). Morlanwelz: Musée royal de Mariemont.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Van den Eynde, Maurice (1970). Monographies du Musée de Mariemont: Raoul Warocqué Seigneur de Mariemont 1870-1917 (in French). Morlanwelz: Musée royal de Mariemont.

Literature[edit]

- Wellens, Robert (1961). "Le domaine de Mariemont au XVIe siècle (1546-1598)". Annales du cercle archéologique de Mons (in French): 79–184.

- Van den Eynde, Maurice (1970). Monographies du Musée de Mariemont: Raoul Warocqué Seigneur de Mariemont 1870-1917 (in French). Morlanwelz: Musée royal de Mariemont.

- Lemoine-Isabeau, Claire; Jottrand, Mireille (1979). "Mariemont au XVIIIe siècle". Les cahiers de Mariemont (in French). 10: 7–61. doi:10.3406/camar.1979.983.

- Demeester, Joélle (1981). "Le domaine de Mariemont sous Albert et Isabelle (1598-1621)". Annales du cercle archéologique de Mons (in French): 181–282.

- Quairiaux, Yves (1987). "Mariemont et le commerce de la pierre au 18e siècle". Les cahiers de Mariemont (in French). 18: 6–45. doi:10.3406/camar.1987.1048.

- Donnay, Guy, ed. (1993). Guide du parc et du Musée de Mariemont (in French). Morlanwelz: Musée royal de Mariemont.

- De Jonge, Krista (2005). Jacques du Broeucq de Mons 1505-1584, Maître Artiste de l'Empereur Charles Quint (in French). Mons: Ville Mons. p. 176. ISBN 978-2960054200.

- De Jonge, Krista (2005). "Mariemont, Mary of Hungary's hunting pavilion Mariemont, "château de chasse" de Marie de Hongrie". Revue de l'Art (in French): 45–57. ISSN 0035-1326.

- De Jonge, Krista (2007). "Le parc de Mariemont: chasse et architecture à la cour de Marie de Hongrie (1531 - 1555)". Chasses princières dans l'Europe de la Renaissance (in French): 269–284.

- De Jonge, Krista (2008). "Marie de Hongrie, maitre d'ouvrage (1531-1555), et la Renaissance dans les anciens Pays-Bas". In Federinov, B; Docquier, G (eds.). Monographies du Musée de Mariemont: Marie de Hongrie, Politique et culture sous la Renaissance aux Pays-Bas (in French). Morlanwelz: Musée royal de Mariemont. pp. 124–139.

External links[edit]

- "Official website of the Musée royal de Mariemont". www.musee-mariemont.be. Retrieved 4 May 2023.