Humam-i Tabrizi | |

|---|---|

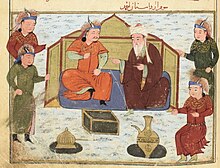

Humam-i Tabrizi and Shirazi Sheikh in a bath. Folio from a manuscript of Nigaristan, Iran, probably Shiraz, dated 1573-74. | |

| Born | 1238/39 |

| Died | 1314/15 (aged 78) |

| Notable works | Divan of Humam-i Tabrizi Suhbat-nama Kitab-i mathnaviyyat |

Humam-i Tabrizi (Persian: همام الدین تبریزی; 1238/39 – 1314/15), was a Persian Sufi poet of the Ilkhanate era.[1][2] He was one of the most distinguished figures of his time due to his poetry, teachings, piety, and Sufi spirituality.

Humam spent most of his life in the city of Tabriz, where he became an influential figure. He became close to the Juvayni family, who lent him political and cultural protection, and helped him establish a khanqah (Sufi lodge) in Tabriz. Following the execution of his Juvayni patron Shams al-Din Juvayni in 1284, Humam managed to find support amongst other political figures, such as Rashid al-Din Hamadani. Humam died at the age of 78, and was buried in the Sorkhab district of Tabriz.

Most of his poetry was in the form of a ghazal, and followed the same style and tone of that of his contemporary Saadi Shirazi. He also wrote two masnavis (poem in rhyming couplets), the Suhbat-nama and Kitab-i mathnaviyyat.

Biography[edit]

Details regarding Humam's early life and education are obscure, including his place of birth. According to Humam's divan (collection of short poems)—which was assembled soon after his death—he died at the age of 78. This demonstrates that Humam was born in 1238/39, as he died in 1314/15.[2] Most of his life, Humam lived in Tabriz, a city in the Azerbaijan region that served the capital of the Mongol Ilkhanate between 1265 and 1307.[3][4] He occasionally took trips to other places, including a visit to Baghdad and a pilgrimage to Mecca.[1]

Most sources accept the account of the biographer Dawlatshah Samarqandi, which claims that Humam was a student of Nasir al-Din al-Tusi.[2] Humam was also a student of Qutb al-Din al-Shirazi, who dedicated his work Miftah al-Miftah ("Key to the Key") to him. The work was a commentary on the Miftah al-'Ulum ("Key to the Sciences"), a textbook composed by Siraj al-Din al-Sakaki and which focused on Arabic rhetoric, grammar, and style. Humam responded by assembling a book of panegyrics as a homage to Qutb al-Din al-Shirazi.[1]

Humam was a Sunni Muslim, as demonstrated by a poem that praises the four caliphs of the Rashidun Caliphate. His Arabic eulogy of two masters of the Sufi Kubrawiya order, Sa'id al-Hamuya and the latter's son Sadr al-Din Ibrahim Hamuya, suggests that Humam was possibly associated with the order.[1] According to Hafiz Husayn ibn Karbala'i, Humam's Sufi master was Hasan Bulghari, whilst the 18th-century text Tadhkira-yi suhuf-i Ibrahim ("Memorial of Abraham's scripture") claims that Humam's master was Sa'id al-Din Farghani. However, neither of those figures are mentioned in Humam's writings.[1]

It was in Tabriz that Humam distinguished himself amongst the political and intellectual figures.[2] He was close to the Juvayni family,[2] from whom he enjoyed political and cultural protection.[5] Humam was provided with the funds to establish a khanqah (Sufi lodge) in Tabriz by Sharaf al-Din Harun Juvayni, whom he dedicated his Suhbat-nama ("Book of companionship") to. Sharaf al-Din Harun Juvayni's father Shams al-Din Juvayni—who was the grand vizier of Ilkhanate—supplied the khanqah with an annual income of 1,000 dinars taken from the court treasury. He referred Humam as an "exemplar for all mortals, the crème de la crème of his epoch… a man unique in his age, the most perfect man in the entire human species."[1]

It was through this khanqah that Humam could enter the spiritual and literary circle of the Persian-speaking political elite.[5] Humam played an important role in the cultural and political environment of Tabriz, during a period which the Ilkhanate rulers were being Islamicized. He regularly wrote ghazals about the religious syncretism of this period, especially under the Ilkhanid ruler Abaqa (r. 1265–1282).[6] Humam was later given the honour of accompanying Shams al-Din Juvayni on his assignment to Anatolia as advisor to the vizier of the Sultanate of Rum, Mu'in al-Din Parwana. Humam returned the favour by inviting Shams al-Din Juvayni to a grand meal served on four hundred Chinese plates.[1]

On the accusation of financial misappropriation, Shams al-Din Juvayni was executed on 17 October 1284.[7] He left a goodbye letter, which specifically mentions Humam when addressing the clerics of Tabriz.[1] Although Humam was close to the Juvayni family, the execution of Shams al-Din Juvayni did not hurt his career. He managed to affiliate himself with the grand vizier Sa'd al-Din Savaji, and then the latter's successor, Rashid al-Din Hamadani, whom Humam dedicated much of his work to. Humam also found support amongst the Ilkhanid Sultans Tekuder (r. 1282–1284), Ghazan (r. 1295–1304) and Öljaitü (r. 1304–1316).[8]

Humam died in 1314/15 at the age of 78, and was buried in the Sorkhab district of Tabriz.[1] Soon after his death, Rashid al-Din Hamadani assembled his divan, which included both poetry in Arabic and Persian.[2] Humam's khanqah was still active in 1487, as reported by Dawlatshah.[1]

Works[edit]

Humam's poetry was influenced by poets such as Sanai, Anvari, and Saadi Shirazi.[2]

In 1972, the historian Rashid Ayvadi composed a critical edition of Humam's divan, which encompasses 220 ghazals, and thus around 3944 couplets, 165 of which are in Arabic. The divan starts with five ghazals, then a qasida (eulogy or ode), followed by a poem praising the Islamic prophet Muhammad, and then various panegyrics about distinguished politicians and rulers of the Ilkhanate realm, such as Shams al-Din Juvayni, Rashid al-Din Hamadani, Sultan Tekuder, and Sultan Öljaitü. Humam also wrote many qasidas in honour of several Sufi masters.[1]

Humam is known to have written two masnavis (poem in rhyming couplets); the first was Suhbat-nama, a treatise on love, which he completed in his mid-40s.[1][2] The second was the bigger Kitab-i mathnaviyyat ("Book of epic verses"), which he completed in his final years. The latter was written in the same metre as the influential poem Hadiqat al-haqiqat ("The enclosed garden of truth") by Sanai.[1]

Humam considered Saadi to be the greatest writer of the romantic ghazal genre, and imitated his style and tone.[2] Like Saadi, Humam focuses mostly on the topic of love; majaz (figurative, human romantic love) and especially haqiqi (divine love). Humam wrote also verse replies to the majority of Saadi's ghazals and qasidas.[1] Because of this, Humam was later referred to as "the Saadi of Azerbaijan."[2]

One of Humam's ghazals was written in two languages mixed together, which according to the Iranologist Ehsan Yarshater, was a mix of Persian and Old Azeri, the latter which was an Iranian language native to Azerbaijan.[9]

Legacy and assessment[edit]

The Iranologist Richard N. Frye included Humam amongst the "finest Persian writers and poets of classical Persian" that Azerbaijan had produced.[10] Leonard Lewisohn calls him one of the most distinguished figures of his time due to his poetry, teachings, piety, and Sufi spirituality. According to the modern historian Dhabihallah Safa; "despite the fact that he was influenced heavily by Saadi's ghazals, Humam has his own original and sweet style; his thematic inventiveness is charming and fresh, and in poetic art he holds a high degree."[1]

In the mathnavi Ushshaq-nama ("Book of lovers") by Ubayd Zakani, Humam is called one of the greatest masters. Other poets such as Hafez and Kamal Khujandi also commended Humam by citing his lines, while Muhammad Shirin Maghribi Tabrizi imitated his style in seven of his ghazals. Amir Khusrau considered Humam along with Saadi "the only two perfect masters of the genre of the Persian ghazal."[1]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Lewisohn 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Hanaway & Lewisohn 2004, pp. 434–435.

- ^ Minorsky & Blair 2000, p. 44.

- ^ Woods & Tucker 2006, p. 530.

- ^ a b Ingenito 2013, p. 77.

- ^ Ingenito 2013, p. 81.

- ^ Biran 2009, pp. 71–74.

- ^ Lane 2003, p. 242.

- ^ Yarshater 1988, pp. 238–245.

- ^ Frye 2004, pp. 321–326.

Sources[edit]

- Biran, Michal (2009). "Jovayni, Ṣāḥeb Divān". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). Encyclopædia Iranica, Volume XV/1: Joči–Judeopersian communities of Iran V. Qajar period (1786-1925). London and New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul. pp. 71–74. ISBN 978-1-934283-14-1.

- Frye, R. N. (2004). "Iran v. Peoples of Iran (1) A General Survey". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). Encyclopædia Iranica, Volume XIII/3: Iran II. Iranian history–Iran V. Peoples of Iran. London and New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul. pp. 321–326. ISBN 978-0-933273-89-4.

- Hanaway, William; Lewisohn, Leonard (2004). "Homām-al-Din". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). Encyclopædia Iranica, Volume XII/4: Historiography III–Homosexuality III. London and New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul. pp. 434–435. ISBN 978-0-933273-78-8.

- Ingenito, Domenico (2013). "'Tabrizis in Shiraz are Worth Less than a Dog:' Sa'dī and Humām, a Lyrical Encounter". In Pfeiffer, Judith (ed.). Politics, Patronage and the Transmission of Knowledge in 13th - 15th Century Tabriz. Brill. pp. 77–129. doi:10.1163/9789004262577_005. ISBN 978-9004255395.

- Lane, George (2003). Early Mongol Rule in Thirteenth-Century Iran: A Persian Renaissance. Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203417874. ISBN 978-0415297509.

- Lewisohn, Leonard (2016). "Humām al-Dīn al-Tabrīzī". In Fleet, Kate; Krämer, Gudrun; Matringe, Denis; Nawas, John; Rowson, Everett (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam (3rd ed.). Brill Online. doi:10.1163/1573-3912_ei3_COM_30552. ISSN 1873-9830.

- Minorsky, V. & Blair, Sheila (2000). "Tabrīz". In Bearman, P. J.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E. & Heinrichs, W. P. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume X: T–U. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 41–50. doi:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_COM_1137. ISBN 978-90-04-11211-7.

- Woods, John E.; Tucker, Ernest (2006). History and Historiography of Post-Mongol Central Asia and the Middle East: Studies in Honor of John E. Woods. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 978-9004255395.

- Yarshater, E. (1988). "Azerbaijan vii. The Iranian Language of Azerbaijan". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). Encyclopædia Iranica, Volume III/3: Azerbaijan IV–Bačča(-ye) Saqqā. London and New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul. pp. 238–245. ISBN 978-0-71009-115-4.