ʿAbd al-Raḥmān ibn Naṣr ibn ʿAbdallāh (died 1193), called al-Shayzarī or al-Nabarāwī, was a Syrian Arabic author on various topics. He wrote a work on the proper behaviour of a ruler for Saladin, a work on various drugs and other remedies for sexual and erotic needs, a work on the interpretation of dreams and a manual for the muḥtasib (market supervisor).

Life[edit]

The full name of al-Shayzarī is uncertain. His given name and patronymic, ʿAbd al-Raḥmān ibn Naṣr ibn ʿAbdallāh, appear consistently the same, but his laqab (cognomen) and nisba (surname) vary in the manuscripts. His laqab appears as Taqī al-Dīn, Zayn al-Dīn or Jamāl al-Dīn, while his nisba may be al-Nibrāwī, al-Ṭabrīzī, al-ʿAdawī, al-Shīrāzī or al-Shayzarī.[1] Carl Brockelmann gives his full name as Jalāl al-Dīn Abu ʾl-Najīb Abi ʾl-Faḍāʾil ʿAbd al-Raḥmān ibn Naṣr Allāh ibn ʿAbdallāh ibn Naṣr ibn ʿAbdallāh al-Shayzarī al-Ṭabrīzī al-ʿAdawī al-Nabarāwī.[2] Given the prominence of Shayzar in his work, al-Shayzarī is his most likely nisba.[1]

Little is known of al-Shayzarī's life, since he does not appear in the classical biographical dictionaries. He was a contemporary of Saladin (r. 1174–1193).[1] According to Ibn Qādī Shahbā's al-Kawākib al-durrīya fiʾ l-sīrat al-Nūrīya, written some three centuries later, al-Shayzarī was a native of Syria.[3] This is consistent with the internal evidence of his writings, which indicates at least that he spent much time in Syria. Later sources are even more specific. According to Ḥājjī Khalīfa, he was a judge in Tiberias; per Ferdinand Wüstenfeld, a physician in Aleppo. His writings do not reveal his occupation, although it has sometimes been assumed he was a muḥtasib.[4]

Al-Shayzarī may have died in 1193, the same year as Saladin.[5]

Works[edit]

Five works in Arabic are attributed to al-Shayzarī.[6]

- al-Nahj al-maslūk fī siyāsat al-mulūk is a mirror for princes dedicated to Saladin. It was first printed in 1840.[3] There is a Turkish translation.[2]

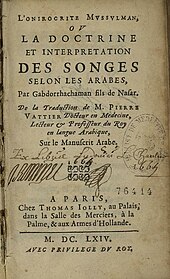

- Khulāṣat al-kalām fī taʾwīl al-aḥlām is a work on the interpretation of dreams.[7] It was translated into French by Pierre Vattier and published at Paris in 1664 under the title L'Onirocrite mussulman ou la Doctrine et interpretation des songes selon les arabes par Gabdorrhachaman fils de Nasar.[2]

- Rawḍat al-qulūb wa-nuzhat al-muḥibb wal-maḥbūb is a treatise on love.[6] It consists mostly of anecdotes and poems. As typical of the "love theory" tradition, the love in question is mostly chaste, although the penultimate chapter is unusually racy. The final chapter consists of poems on fruit and flowers with no relation to love.[8]

- al-Īḍāḥ fī asrār al-nikāḥ is divided into two parts of ten chapters each, "Secrets of Men" and "Secrets of Women".[2] It mostly concerns aphrodisiacs, contraceptives, cosmetics, drugs for controlling sexual desire and erotic spells.[9] It was a popular work and widely copied. It cites Galen and Hippocrates. Neẓām-e Motašahhī (or Monšī) translated it into Persian in 1423 as Ganǰ-e asrār. He expanded it with material of his own, almost doubling its size.[3] There is also a Turkish translation.[2]

- Nihāyat al-rutba fī ṭalab al-ḥisba is a detailed description of ḥisba or the regulation of the marketplace. It was a practical manual and highly influential in its genre, being the first such manual produced in the Islamic East.[7] The manuals of Ibn al-Ukhuwwa and Ibn Bassām borrow extensively from it verbatim. Fourteen manuscript copies of the Nihāyat are known.[10] It has been translated into English as The Utmost Authority in the Pursuit of Ḥisba.[11]

Notes[edit]

- ^ a b c Buckley 1999, p. 12.

- ^ a b c d e Brockelmann 2017, p. 865 (pp. 832–833 in the original German).

- ^ a b c Biesterfeldt 2011.

- ^ Buckley 1999, pp. 12–13; Biesterfeldt 2011. Needham 1986, p. 80, citing Wiedemann 1914, calls him a pharmacist.

- ^ Brockelmann 2017, p. 865; Buckley 1999, p. 12; Biesterfeldt 2011; Needham 1986, p. 80.

- ^ a b Brockelmann 2017, p. 865; Buckley 1999, p. 13; Biesterfeldt 2011.

- ^ a b Buckley 1999, p. 13; Biesterfeldt 2011.

- ^ Rowson 2008, reviewing Semah & Kanazi 2003.

- ^ Brockelmann 2017, p. 865; Biesterfeldt 2011.

- ^ Buckley 1999, pp. 13–14.

- ^ Buckley 1999.

Bibliography[edit]

- Biesterfeldt, H. H. (2011). "ʿAbd-al-Raḥmān Šayzarī". Encyclopædia Iranica. Vol. 1, Fasc. 2. p. 143. Retrieved 2 September 2023.

- Brockelmann, Carl (2017). History of the Arabic Written Tradition. Vol. Suppl. 1. Translated by Joep Lameer. Brill.

- Buckley, R. P., ed. (1999). The Book of the Islamic Market Inspector: Nihāyat al-Rutba fī Ṭalab al-Ḥisba (The Utmost Authority in the Pursuit of Ḥisba) by ʿAbd al-Raḥmān b. Naṣr al-Shayzarī. Oxford University Press.

- Cahen, Claude & Talbi, Mohamed (1971). "Ḥisba, I. General: Sources, Origins, Duties". In Lewis, B.; Ménage, V. L.; Pellat, Ch. & Schacht, J. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume III: H–Iram. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 485–489. OCLC 495469525.

- Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilisation in China. Vol. 5: Chemistry and Chemical Technology. Part 7: Military Technology, The Gunpowder Epic. Cambridge University Press.

- Rowson, Everett K. (2008). "Review of Semah & Kanazi 2003". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 128 (2): 380–382. JSTOR 25608383.

- Semah, David (1977). "Rawḍat al-Qulūb by al-Šayzarī: A Twelfth-Century Book on Love". Arabica. 24 (Fasc. 2): 187–206. JSTOR 4056233.

- Semah, David; Kanazi, George J., eds. (2003). Rawḍat al-Qulūb wa-Nuzhat al-Muḥibb wal-Maḥbūb, by 'Abd al-Raḥmān ibn Naṣr al-Shayzarī. Harrassowitz Verlag.

- Wiedemann, Eilhard (1914). "Über Verfälschungen von Drogen u.s.w. nach Ibn Bassām und Nabarāwī". Beiträge zur Geschichte der Naturwissenschaften. 46: 172–206.