| Haramiyida | |

|---|---|

| |

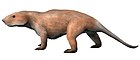

| Lower jaw and restoration of Haramiyavia, a basal haramiyidan from the Triassic of Greenland | |

| |

| Skull of Xianshou, a euharamiyidan from the Jurassic of China | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Synapsida |

| Clade: | Therapsida |

| Clade: | Cynodontia |

| Clade: | Mammaliaformes |

| Order: | †Haramiyida Hahn, Sigogneau-Russell & Wouters, 1989 |

| Subgroups | |

Haramiyida is a possibly polyphyletic order of mammaliaform cynodonts or mammals of controversial taxonomic affinites.[2] Their teeth, which are by far the most common remains, resemble those of the multituberculates. However, based on Haramiyavia, the jaw is less derived; and at the level of evolution of earlier basal mammals like Morganucodon and Kuehneotherium, with a groove for ear ossicles on the dentary.[3] Some authors have placed them in a clade with Multituberculata dubbed Allotheria within Mammalia.[4][5] Other studies have disputed this and suggested the Haramiyida were not crown mammals, but were part of an earlier offshoot of mammaliaformes instead.[6] It is also disputed whether the Late Triassic species are closely related to the Jurassic and Cretaceous members belonging to Euharamiyida/Eleutherodontida, as some phylogenetic studies recover the two groups as unrelated, recovering the Triassic haramiyidians as non-mammalian cynodonts, while recovering the Euharamiyida as crown-group mammals closely related to multituberculates.[7]

Relationships[edit]

Haramiyids show certain similarities to multituberculates, a group of mammals that survived until about 40 million years ago. It is possible that haramiyids are ancestral to multituberculates, although the available evidence is insufficient to be conclusive. Certain characteristics of the teeth seem to rule out a special relationship between the two groups,[8] although some studies still unite haramiyids (or at least euharamiyids) and multituberculates in the Allotheria hypothesis.[9]

In a 2018 study, haramiyidans have been found to be a monophyletic group of non-mammalian Mammaliaformes. In this study, gondwanatheres – usually interpreted as mammals, and derived multituberculates in particular – have been found to be deeply nested among them.[10]

Taxonomy[edit]

Order †Haramiyida[11][12] Hahn, Sigogneau-Russell & Wouters, 1989 [Haramiyoidea Hahn, 1973 sensu McKenna & Bell, 1997]

- †Kirtlingtonia Butler & Hooker, 2005

- Family †Haramiyaviidae Butler, 2000

- †Haramiyavia Jenkins et al., 1997

- Family †Theroteinidae Sigogneau-Russell, Frank & Hammerle, 1986

- †Theroteinus nikolai Sigogneau-Russell, Frank & Hammerle, 1986

- †Theroteinus rosieriensis Sigogneau-Russell, 2016[13]

- Family †Haramiyidae Poche, 1908 [Haramiyidae Simpson, 1947 sensu Jenkins et al., 1997; Microlestidae Murry, 1866; Microcleptidae Simpson, 1928]

- †Eoraetica

- †Hypsiprymnopsis rhaeticus Dawkins, 1864[14] [Microlestes rhaeticus Dawkins, 1864]

- †Avashishta bacharamensis Anantharaman et al., 2006

- ?†Allostaffia aenigmatica (Heinrich, 1999) Heinrich 2004 [Staffia Heinrich, 1999 non Schubert, 1911; Staffia aenigmatica Heinrich, 1999]; possible, gondwanathere instead.[15]

- †Thomasia Poche, 1908 [Haramiya Simpson, 1947; Microlestes Plieninger, 1847 non Schmidt-Goebel, 1846; Microcleptes Simpson, 1928 non Newman, 1840; Plieningeria Krausse, 1919; Stathmodon Henning, 1911]

- †T. woutersi Butler & MacIntyre, 1994

- †T. hahni Butler & MacIntyre, 1994

- †T. moorei (Owen 1871) Butler & MacIntyre, 1994 [Haramiya moorei (Owen, 1871) Simpson, 1947; Microleptes moorei Owen, 1871; Microcleptes moorei (Owen, 1871) Simpson, 1928]

- †T. antiqua (Plieninger, 1847) Poche 1908 [Microlestes antiquus Plieninger, 1847; Haramiya antiqua (Plieninger, 1847); Microleptes fissurae Simpson, 1928; Haramiya fissurae (Simpson 1928); Haramiya butleri Sigogneau-Russell, 1990; Thomasia anglica Simpson, 1928]

- †Hahnodontidae Sigogneau-Russell, 1991

- †Cifelliodon wahkarmoosuch Huttenlocker et al., 2018[10]

- † Denisodon

- † Hahnodon taqueti Sigogneau-Russell, 1991

- †Euharamiyida Bi et al., 1994

- ?†Gondwanatheria Mones, 1987

Lifestyle[edit]

Haramiyids seem to have generally been herbivorous or omnivorous, possibly the first mammalian herbivores; however, the sole haramiyid tested in a study involving Mesozoic mammal dietary habits, Haramiyavia, ranks among insectivorous species.[16] At least some species were very good climbers and were similar to modern day squirrels;[17] and several others have more recently been reassessed as possibly arboreal. General arboreal habits might explain their rarity in the fossil record.[18]

Several euharamiyidans, Maiopatagium, Xianshou, Vilevolodon and Arboroharamiya, took it one step further and developed the ability to glide, having extensive membranes similar to those of modern colugos. In many of these taxa, the coracoid bones (absent in modern therians but present in many other mammal groups, albeit highly reduced) are remarkably large and similar to those of birds and pterosaurs, presumably due to impact stresses at landing.[19][20]

Mammalian tooth marks on dinosaur bones may belong to Sineleutherus, suggesting that some haramiyidans scavenged on dinosaur remains.[21]

Range[edit]

The fossils of Late Triassic Haramiyids are primarily known from Europe and Greenland,[7] while the fossils of Euharamiyids are primarily known from the Middle to Late Jurassic of Asia.[22] Remains of eleutherodontids from Europe are only known from isolated teeth.[7]

The youngest haramiyid fossil genus has been considered to be possibly be Avashishta bacharamensis from the Maastrichtian of India,[23] however, this has not been robustly assessed by phylogenetics.[7] The youngest definitive euharamiyidan is Cryoharamiya from the Early Cretaceous Batylykh Formation of Yakutia, Russia.[22]

Notes[edit]

- ^ MUSSER, A.M., LAMANNA, M.C., MARTINELLI, A.G., SALISBURY, S.W., AHYONG, S. & JONES, R., 2019. The first non-mammalian cynodonts from Australia and the unusual nature of Australian Cretaceous terrestrial tetrapod faunas. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 39, Society of Vertebrate Paleontology Annual Meeting Abstracts, 157.

- ^ Zheng, Xiaoting; Bi, Shundong; Wang, Xiaoli; Meng, Jin (2013). "A new arboreal haramiyid shows the diversity of crown mammals in the Jurassic period". Nature. 500 (7461): 199–202. Bibcode:2013Natur.500..199Z. doi:10.1038/nature12353. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 23925244. S2CID 2164378.

- ^ Butler PM, 2000

- ^ Meng, Jin; Bi, Shundong; Wang, Yuanqing; Zheng, Xiaoting; Wang, Xiaoli (2014-12-10). Evans, Alistair R. (ed.). "Dental and Mandibular Morphologies of Arboroharamiya (Haramiyida, Mammalia): A Comparison with Other Haramiyidans and Megaconus and Implications for Mammalian Evolution". PLOS ONE. 9 (12): e113847. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0113847. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4262285. PMID 25494181.

- ^ Bi, Shundong; Wang, Yuanqing; Guan, Jian; Sheng, Xia; Meng, Jin (2014-10-30). "Three new Jurassic euharamiyidan species reinforce early divergence of mammals". Nature. 514 (7524): 579–584. doi:10.1038/nature13718. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 25209669. S2CID 4471574.

- ^ Luo, Zhe-Xi; Gates, Stephen M.; Jenkins Jr., Farish A.; Amaral, William W.; Shubin, Neil H. (16 November 2015). "Mandibular and dental characteristics of Late Triassic mammaliaform Haramiyavia and their ramifications for basal mammal evolution". PNAS. 112 (51): E7101–E7109. Bibcode:2015PNAS..112E7101L. doi:10.1073/pnas.1519387112. PMC 4697399. PMID 26630008.

- ^ a b c d Hoffmann, Simone; Beck, Robin M. D.; Wible, John R.; Rougier, Guillermo W.; Krause, David W. (2020-12-14). "Phylogenetic placement of Adalatherium hui (Mammalia, Gondwanatheria) from the Late Cretaceous of Madagascar: implications for allotherian relationships". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 40 (sup1): 213–234. doi:10.1080/02724634.2020.1801706. ISSN 0272-4634. S2CID 230968231.

- ^ Monastersky 1996, p.379

- ^ Butler & Hooker 2005, p.206

- ^ a b Huttenlocker, Adam K.; Grossnickle, David M.; Kirkland, James, I.; Schultz, Julia A.; Luo, Zhe-Xi (23 May 2018). "Late-surviving stem mammal links the lowermost Cretaceous of North America and Gondwana". Nature. 558 (7708): 108–112. doi:10.1038/s41586-018-0126-y. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- ^ Mikko's Phylogeny Archive [1] Haaramo, Mikko (2007). "†Haramiyida". Retrieved 30 December 2015.

- ^ Paleofile.com (net, info) [2]. "Taxonomic lists – Mammals". Retrieved 30 December 2015.

- ^ Debuysschere, Maxime (2016). "A reappraisal of Theroteinus (Haramiyida, Mammaliaformes) from the Upper Triassic of Saint-Nicolas-de-Port (France)". PeerJ. 4: e2592. doi:10.7717/peerj.2592. PMC 5075691. PMID 27781174.

- ^ Dawkins, W.B. (1864). "On the Rhaetic beds and White Lias of western and central Somerset; and on the discovery of a new fossil mammal in the grey marlstones below the bone-bed". Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society. 20: 396–412. doi:10.1144/GSL.JGS.1864.020.01-02.49. S2CID 128992830.

- ^ Nicholas Chimento, Frederico Agnolin, Agustin Martinelli, Mesozoic Mammals from South America: Implications for understanding early mammalian faunas from Gondwana, May 2016

- ^ David M. Grossnickle, P. David Polly, Mammal disparity decreases during the Cretaceous angiosperm radiation, Published 2 October 2013.DOI: 10.1098/rspb.2013.2110

- ^ "Three extinct squirrel-like species discovered". ScienceDaily. 2014-09-11. Archived from the original on 18 September 2014. Retrieved 2014-10-07.

- ^ Jing Meng, Mesozoic mammals of China: implications for phylogeny and early evolution of mammals, Natl Sci Rev (December 2014) 1 (4): 521-542. doi: 10.1093/nsr/nwu070 First published online: October 17, 2014

- ^ Qing-Jin Meng; David M. Grossnickle; Di Liu; Yu-Guang Zhang; April I. Neander; Qiang Ji; Zhe-Xi Luo (2017). "New gliding mammaliaforms from the Jurassic". Nature. in press. doi:10.1038/nature23476.

- ^ A Jurassic gliding euharamiyidan mammal with an ear of five auditory bones, Nature doi:10.1038/nature24483

- ^ Augustin, Felix J.; Matzke, Andreas T.; Maisch, Michael W.; Hinz, Juliane K.; Pfretzschner, Hans-Ulrich (2020). "The smallest eating the largest: The oldest mammalian feeding traces on dinosaur bone from the Late Jurassic of the Junggar Basin (Northwestern China)". The Science of Nature. 107 (4): 32. Bibcode:2020SciNa.107...32A. doi:10.1007/s00114-020-01688-9. PMC 7369264. PMID 32686025.

- ^ a b Averianov, Alexander O.; Martin, Thomas; Lopatin, Alexey V.; Skutschas, Pavel P.; Schellhorn, Rico; Kolosov, Petr N.; Vitenko, Dmitry D. (2019-11-02). "A new euharamiyidan mammaliaform from the Lower Cretaceous of Yakutia, Russia". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 39 (6): e1762089. doi:10.1080/02724634.2019.1762089. ISSN 0272-4634. S2CID 220548470.

- ^ Anantharaman, S.; Wilson, G. P.; Das Sarma, D. C.; Clemens, W. A. (2006). "A possible Late Cretaceous "haramiyidan" from India". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 26 (2): 488–490. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2006)26[488:aplchf]2.0.co;2. S2CID 41722902.

References[edit]

- Zofia Kielan-Jaworowska, Richard L. Cifelli, and Zhe-Xi Luo, Mammals from the Age of Dinosaurs: Origins, Evolution, and Structure (New York: Columbia University Press, 2004), 249–260.

External links[edit]

- Palaeos, Mammaliaformes: Allotheria

- John H Burkitt, Mammals, A World Listing of Living and Extinct Species. Archived from the original on 21 December 2004. Retrieved 2015-06-18.

- Mikko K Haaramo, Haramiyida