Lysenkoism (Russian: Лысенковщина, romanized: Lysenkovshchina, IPA: [lɨˈsɛnkəfɕːʲɪnə]; Ukrainian: лисенківщина, romanized: lysenkivščyna, IPA: [lɪˈsɛnkiu̯ʃtʃɪnɐ]) was a political campaign led by Soviet biologist Trofim Lysenko against genetics and science-based agriculture in the mid-20th century, rejecting natural selection in favour of a form of Lamarckism, as well as expanding upon the techniques of vernalization and grafting.

More than 3,000 mainstream biologists were dismissed or imprisoned, and numerous scientists were executed in the Soviet campaign to suppress scientific opponents. The president of the Soviet Agriculture Academy, Nikolai Vavilov, who had been Lysenko's mentor, but later denounced him, was sent to prison and died there, while Soviet genetics research was effectively destroyed. Research and teaching in the fields of neurophysiology, cell biology, and many other biological disciplines were harmed or banned.

The government of the Soviet Union (USSR) supported the campaign, and Joseph Stalin personally edited a speech by Lysenko in a way that reflected his support for what would come to be known as Lysenkoism, despite his skepticism toward Lysenko's assertion that all science is class-oriented in nature. Lysenko served as the director of the USSR's Lenin All-Union Academy of Agricultural Sciences. Other countries of the Eastern Bloc including the People's Republic of Poland, the Republic of Czechoslovakia, and the German Democratic Republic accepted Lysenkoism as the official "new biology", to varying degrees, as did the People's Republic of China for some years.

Context[edit]

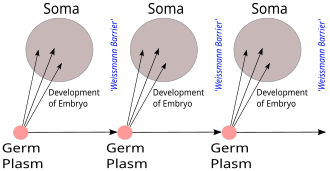

Mendelian genetics, the science of heredity, developed into an experimentally based field of biology at the start of the 20th century through the work of August Weismann, Thomas Hunt Morgan, and others, building on the rediscovered work of Gregor Mendel. They showed that the characteristics of an organism are carried by inherited genes, which were located on chromosomes in each cell's nucleus. Genes can be affected by random changes (mutations), and can be shuffled and recombined during sexual reproduction, but are otherwise passed on unchanged from parent to offspring. Beneficial changes can propagate through a population by natural selection or, in agriculture, by plant breeding.[2] Some Marxists, however, perceived the mechanism of individual random mutations bequeathed to subsequent generations as contravening the Marxist framework of "immutable laws of history" and the spirit of collectivism, and considered it a liberal doctrine.[3]

In contrast, Lamarckism proposed that an organism can somehow pass on characteristics that it has acquired during its lifetime to its offspring, implying that changing the body can affect the genetic material in the germ line.[2][4]

Marxism–Leninism, which became the official ideology in Stalin's USSR, incorporated Darwinian evolution as a foundational doctrine, providing a scientific basis for its state atheism. Initially, the Lamarckian principle of inheritance of acquired traits was considered a legitimate part of evolutionary theory, and Darwin himself recognized its importance.[5] Although the Mendelian view had largely replaced Lamarckism in western biology by 1925,[5] it persisted in Soviet doctrine. Besides the fervent "old style" Darwinism of Marx and Engels which included elements of Lamarckism, two fallacious experimental results supported it in the USSR. First, Ivan Pavlov, who discovered conditioned reflex, initially announced that it can be inherited in mice;[5] and his subsequent withdrawal of this claim was ignored by Soviet ideologists.[5] Second, Ivan Michurin interpreted his work on plant breeding as proof of the inheritance of acquired traits.[5]

Soviet agriculture around 1930 was in a crisis due to Stalin's forced collectivisation of farms and extermination of kulak farmers. The resulting Soviet famine of 1932–1933 provoked the government to search for a technical solution which would maintain their central political control.[6]

In the Soviet Union[edit]

Lysenko's claims[edit]

In 1928, rejecting natural selection and Mendelian genetics, Trofim Lysenko claimed to have developed agricultural techniques which could radically increase crop yields. These included vernalization, species transformation, inheritance of acquired characteristics, and vegetative hybridization.[2] He claimed in particular that vernalization, exposing wheat seeds to humidity and low temperature, could greatly increase crop yield. He claimed further that he could transform one species, Triticum durum (durum spring wheat), into Triticum vulgare (common autumn wheat), through 2 to 4 years of autumn planting. However this was already known to be impossible since T. durum is a tetraploid with 28 chromosomes (4 sets of 7), while T. vulgare is hexaploid with 42 chromosomes (6 sets).[2]

Lysenko claimed that the concept of gene is a "bourgeois invention", and he denied presence of any "immortal substance of heredity" or "clearly defined species", which he claimed belong to Platonic metaphysics rather than strictly materialist Marxist science. Instead, he proposed a "Marxist genetics" postulating an unlimited possibility of transformation of living organisms through environmental changes in the spirit of Marxian dialectical transformation, and in parallel to the Party's program of creating the New Soviet Man and subduing nature for his benefit. Lysenko refused to admit random mutations, stating that "science is the enemy of randomness".[7]

Lysenko further claimed that Lamarckian inheritance of acquired characteristics occurred in plants, as in the "eyes" of potato tubers, though the genetic differences in these plant parts were already known to be non-heritable somatic mutations.[2][9] He also claimed that when a tree is grafted, the scion permanently changes the heritable characteristics of the stock. In modern biological theory, such a change is theoretically possible through horizontal gene transfer; however, there is no evidence that this actually occurs, and Lysenko rejected the mechanism of genes entirely.[8]

Rise[edit]

Isaak Izrailevich Prezent, a biologist politically out of favor, brought Lysenko to public attention. He portrayed Lysenko as a genius who had developed a revolutionary technique which could lead to the triumph of Soviet agriculture, a thrilling possibility for a Soviet society suffering through Stalin's famines. Lysenko became a favorite of the Soviet propaganda machine, which overstated his successes, trumpeted his faked experimental results, and omitted any mention of his failures.[10] State media published enthusiastic articles such as "Siberia is transformed into a land of orchards and gardens" and "Soviet people change nature", while anyone opposing Lysenko was presented as a defender of "mysticism, obscurantism and backwardness."[11]

Lysenko's political success was mostly due to his appeal to the Communist Party and Soviet ideology. His attack on the "bourgeois pseudoscience" of modern genetics and the proposal that plants can rapidly adjust to a changed environment suited the ideological battle in both agriculture and Soviet society.[12][8] Following the disastrous collectivization efforts of the late 1920s, Lysenko's new methods were seen by Soviet officials as paving the way to an "agricultural revolution." Lysenko himself was from a peasant family and was an enthusiastic advocate of Leninism.[13][8] The Party-controlled newspapers applauded Lysenko's practical "success" and questioned the motives of his critics, ridiculing the timidity of academics who urged the patient, impartial observation required for science.[13][14] Lysenko was admitted into the hierarchy of the Communist Party, and was put in charge of agricultural affairs.

He used his position to denounce biologists as "fly-lovers and people haters,"[15] and to decry traditional biologists as "wreckers" working to sabotage the Soviet economy. He denied the distinction between theoretical and applied biology, and rejected general methods such as control groups and statistics:[16]

We biologists do not take the slightest interest in mathematical calculations, which confirm the useless statistical formulae of the Mendelists … We do not want to submit to blind chance … We maintain that biological regularities do not resemble mathematical laws.

Lysenko presented himself as a follower of Ivan Vladimirovich Michurin, a well-known and well-liked Soviet horticulturist, but unlike Michurin, Lysenko insisted on using only non-genetic techniques such as hybridization and grafting.[2]

Support from Joseph Stalin confirmed Lysenko's momentum and popularity. In 1935, Lysenko compared his opponents in biology to the peasants who still resisted the Soviet government's collectivization strategy, saying that by opponents of his theories were opponents of Marxism. Stalin was in the audience for this speech, an was the first to stand and applaud, calling out "Bravo, Comrade Lysenko. Bravo."[17] Stalin personally personally made encouraging edits to a speech by Lysenko, despite the dictator's skepticism toward Lysenko's assertion that all science is class-oriented.[18] The official support emboldened Lysenko and gave him and Prezent free rein to slander any geneticists who still spoke out against him. After Lysenko became head of the Soviet Academy of Agricultural Sciences, classical genetics began to be called "fascist science"[19] and many of Lysenkoism's opponents, such as his former mentor Nikolai Ivanovich Vavilov, were imprisoned or executed, although not on Lysenko's personal orders.[20][13]

On August 7, 1948, at the end of a week-long session organized by Lysenko and approved by Stalin,[14] the Academy of Agricultural Sciences announced that Lysenkoism would henceforth be taught as "the only correct theory." Soviet scientists were required to denounce any work that contradicted Lysenko,[21] and criticism was denounced as "bourgeois" or "fascist". The same wave of propaganda supported a number of other pseudo-scientific "new Marxist sciences" in the Soviet academy, in fields such as linguistics and art. Pravda reported the invention of a perpetual motion engine, confirming Engels' claim that energy dissipated in one place must concentrate somewhere else.[7]

A prominent promoter of Lysenkoism was the biologist Olga Lepeshinskaya, who delivered in speech in 1950 in which she equated all of the "bourgeois" heresies:[22]

In our country there are no longer classes hostile to each other, and the struggle of idealists against dialectical materialists still, depending on whose interests it defends, has the character of a class struggle. Indeed, the followers of Virchow, Weismann, Mendel and Morgan, who speak of the invariability of the gene and deny the influence of the external environment, are the preachers of the pseudo-scientific teachings of the bourgeois eugenicists and of all perversions in genetics, on the soil of which grew the racial theory of fascism in the capitalist countries. The Second World War was unleashed by the forces of imperialism, which also had racism in its arsenal.

Perhaps the only opponents of Lysenkoism during Stalin's lifetime to escape liquidation were from the small community of Soviet nuclear physicists: according to Tony Judt, "it is significant that Stalin left his nuclear physicists alone and never presumed to second guess their calculations. Stalin may well have been mad but he was not stupid."[23]

Effects[edit]

From 1934 to 1940, under Lysenko's admonitions and with Stalin's approval, many geneticists were executed (including Izrail Agol, Solomon Levit, Grigorii Levitskii, Georgii Karpechenko and Georgii Nadson) or sent to labor camps. The famous Soviet geneticist and president of the Agriculture Academy, Nikolai Vavilov, was arrested in 1940 and died in prison in 1943.[24] In 1936, the American geneticist Hermann Joseph Muller, who had moved to the Leningrad Institute of Genetics with his Drosophila fruit flies, was criticized as bourgeois, capitalist, imperialist, and a promoter of fascism, and he returned to America via Republican Spain.[25]

In 1948, genetics was officially declared "a bourgeois pseudoscience".[26] Over 3,000 biologists were imprisoned, fired[27] or executed for attempting to oppose Lysenkoism, and genetics research was effectively destroyed until the death of Stalin in 1953.[28][29] Soviet crop yields declined.[30][31][28]

Fall[edit]

At the end of 1952, the situation started to change, and newspapers published articles criticizing Lysenkoism. However, the return to regular genetics slowed down in Nikita Khrushchev's time, when Lysenko showed him the supposed successes of an experimental agricultural complex. It was once again forbidden to criticize Lysenkoism, though it was now possible to express different views, and the geneticists imprisoned under Stalin were released or rehabilitated posthumously. The ban was finally lifted in the mid-1960s.[32][33] In the West, meanwhile, Lysenkoism increasingly became seen as pseudoscience.[34]

Reappearance[edit]

In the 21st century, Lysenkoism is again being discussed in Russia, including in respectable newspapers like Kultura and by biologists.[33] The geneticist Lev Zhivotovsky has made the unsupported claim that Lysenko helped found modern developmental biology.[33] Discoveries in the field of epigenetics are sometimes raised as alleged late confirmation of Lysenko's theories, but in spite of the apparent high-level similarity (heritable traits passed on without DNA alteration), Lysenko believed that environment-induced changes are the primary mechanism of heritability. Heritable epigenetic effects have been found, but are minor and unstable compared to genetic inheritance.[35]

In other countries[edit]

Other countries of the Eastern Bloc accepted Lysenkoism as the official "new biology", to varying degrees.

In Communist Poland, Lysenkoism was aggressively pushed by state propaganda. State newspapers attacked "damage caused by bourgeois Mendelism-Morganism" and "imperialist genetics", comparing it to Mein Kampf. For example, Trybuna Ludu published an article titled "French scientists recognize superiority of Soviet science" by Pierre Daix, a French communist and chief editor of Les Lettres Françaises, basically repeating Soviet propaganda claims; this was intended to create an impression that Lysenkoism was accepted by the whole progressive world.[11] While some academics accepted Lysenkoism for political reasons, the Polish scientific community largely opposed it.[36] A notable opponent was Wacław Gajewski: in retaliation, he was denied contact with students, though he allowed to continue his scientific work at the Warsaw botanical garden. Lysenkoism was rapidly rejected starting from 1956, and in 1958 Gajewski founded the first department of genetics, at the University of Warsaw.[36]

Communist Czechoslovakia adopted Lysenkoism in 1949. The prominent geneticist Jaroslav Kříženecký (1896–1964) criticized Lysenkoism in his lectures, and was dismissed from the Agricultural University in 1949 for "serving the established capitalistic system, considering himself superior to the working class, and being hostile to the democratic order of the people"; he was imprisoned in 1958.[37]

In the German Democratic Republic, although Lysenkoism was taught at some universities, it had very little impact on science due to the actions of a few scientists, such as the geneticist Hans Stubbe, and scientific contact with West Berlin research institutions. Nonetheless, Lysenkoist theories were found in schoolbooks as late as the dismissal of Nikita Khrushchev in 1964.[38]

Lysenkoism dominated Chinese science from 1949 until 1956, particularly during the Great Leap Forward, when, during a genetics symposium opponents of Lysenkoism were permitted to freely criticize it and argue for Mendelian genetics.[39] In the proceedings from the symposium, Tan Jiazhen is quoted as saying "Since [the] USSR started to criticize Lysenko, we have dared to criticize him too".[39] For a while, both schools were permitted to coexist, although the influence of the Lysenkoists remained large for several years, contributing to the Great Famine through loss of yields.[39]

Almost alone among Western scientists, John Desmond Bernal, Professor of Physics at Birkbeck College, London, a Fellow of the Royal Society, and a communist,[40] made an aggressive public defence of Lysenko.[41]

See also[edit]

- Anti-intellectualism

- Deutsche Physik

- Junk science

- Pavlovian session

- Politicization of science

- Suppressed research in the Soviet Union

References[edit]

- ^ Huxley, Julian (1942). Evolution, the Modern Synthesis. p. 17.

- ^ a b c d e f Leone, Charles A. (1952). "Genetics: Lysenko versus Mendel". Transactions of the Kansas Academy of Science. 55 (4): 369–380. doi:10.2307/3625986. ISSN 0022-8443. JSTOR 3625986.

- ^ Kautsky, John H., ed. (1989). "Karl Kautsky: Nature and Society (1929)". www.marxists.org. Retrieved 21 February 2020.

For Marx, the mass is the carrier of development, for Darwin it is the individual, though not as exclusively as for many of his disciples. He by no means rejected the doctrine of Lamarck who regarded the progressive adaptation of organisms to the environment as the most important factor in their development.

- ^ Ghiselin, Michael T. (1994). "The Imaginary Lamarck: A Look at Bogus "History" in Schoolbooks". The Textbook Letter (September–October 1994). Archived from the original on 12 October 2000. Retrieved 12 December 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Caspari, E. W.; Marshak, R. E. (16 July 1965). "The Rise and Fall of Lysenko". Science. 149 (3681). New Series: 275–278. Bibcode:1965Sci...149..275C. doi:10.1126/science.149.3681.275. JSTOR 1715945. PMID 17838094.

- ^ Ellman, Michael (June 2007). "Stalin and the Soviet Famine of 1932–33 Revisited". Europe-Asia Studies. 59 (4): 663–693. doi:10.1080/09668130701291899. S2CID 53655536. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-10-14. Retrieved 2019-12-12.

- ^ a b Kolakowski, Leszek (2005). Main Currents of Marxism. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0393329438.

- ^ a b c d Liu, Yongsheng; Li, Baoyin; Wang, Qinglian (2009). "Science and politics". EMBO Reports. 10 (9): 938–939. doi:10.1038/embor.2009.198. ISSN 1469-221X. PMC 2750069. PMID 19721459.

- ^ Asseyeva, T. (1927). "Bud mutations in the potato and their chimerical nature" (PDF). Journal of Genetics. 19: 1–28. doi:10.1007/BF02983115. S2CID 6762283.

- ^ Rispoli, Giulia (2014). "The Role of Isaak Prezent in the Rise and Fall of Lysenkoism". Ludus Vitalis. 22 (42). Archived from the original on 2019-12-12. Retrieved 2019-12-12.

- ^ a b "Lysenkoist propaganda in Trybuna Ludu". cyberleninka.ru. Retrieved 2020-06-07.

- ^ Geller, Mikhail (1988). Cogs in the wheel : the formation of Soviet man. Knopf. ISBN 978-0394569260.

- ^ a b c Graham, Loren R. (1993). Science in Russia and the Soviet Union: A Short History. Cambridge University Press. pp. 124–128. ISBN 978-0-521-28789-0.

- ^ a b Borinskaya, Svetlana A.; Ermolaev, Andrei I.; Kolchinsky, Eduard I. (2019). "Lysenkoism Against Genetics: The Meeting of the Lenin All-Union Academy of Agricultural Sciences of August 1948, Its Background, Causes, and Aftermath". Genetics. 212 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1534/genetics.118.301413. ISSN 0016-6731. PMC 6499510. PMID 31053614.

- ^ Epistemology and the Social, Evandro Agazzi, Javier Echeverría, Amparo Gómez Rodríguez, Rodopi, 2008, "Philosophy", p. 149

- ^ Faulk, Chris (2013-06-21). "Lamarck, Lysenko, and Modern Day Epigenetics". Mind the Science Gap. Retrieved 2020-06-06.

- ^ Cohen, Richard (3 May 2001). "Political Science". The Washington Post.

- ^ Rossianov, Kirill O. (1993). "Editing Nature: Joseph Stalin and the "New" Soviet Biology". Isis. 84 (December 1993): 728–745. doi:10.1086/356638. JSTOR 235106. PMID 8307727. S2CID 38626666.

- ^ deJong-Lambert, William (2017). The Lysenko Controversy as a Global Phenomenon, Volume 1: Genetics and Agriculture in the Soviet Union and Beyond. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 6. ISBN 978-3319391755.

- ^ Harper, Peter S. (2017). "Lysenko and Russian genetics: Reply to Wang & Liu". European Journal of Human Genetics. 25 (10): 1098. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2017.118. ISSN 1018-4813. PMC 5602019. PMID 28905879.

- ^ Wrinch, Pamela N. (July 1951). "Science and Politics in the U.S.S.R.: The Genetics Debate". World Politics. 3 (4): 486–519. doi:10.2307/2008893. JSTOR 2008893. S2CID 146284128.

- ^ "Лепешинская О.Б. Развитие жизненных процессов в доклеточном периоде". www.bioparadigma.spb.ru. Retrieved 2023-08-27.

- ^ Judt, Tony (2006). Postwar: A History of Europe Since 1945. New York: Penguin Books. p. 174n.

- ^ Cohen, Barry Mandel (1991). "Nikolai Ivanovich Vavilov: the explorer and plant collector". Economic Botany. 45 (1 (Jan-Mar 1991)): 38–46. doi:10.1007/BF02860048. JSTOR 4255307. S2CID 27563223.

- ^ Carlson, Elof Axel (1981). Genes, radiation, and society: the life and work of H. J. Muller. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. pp. 184–203. ISBN 978-0801413049.

- ^ Gardner, Martin (1957). Fads and Fallacies in the Name of Science. New York: Dover Books. pp. 140–151. ISBN 978-0486131627.

- ^ Birstein, Vadim J. (2013). The Perversion Of Knowledge: The True Story Of Soviet Science. Perseus Books Group. ISBN 9780786751860. Retrieved 2016-06-30.

Academician Schmalhausen, Professors Formozov and Sabinin, and 3,000 other biologists, victims of the August 1948 Session, lost their professional jobs because of their integrity and moral principles [...]

- ^ a b Soyfer, Valery N. (1 September 2001). "The Consequences of Political Dictatorship for Russian Science". Nature Reviews Genetics. 2 (9): 723–729. doi:10.1038/35088598. PMID 11533721. S2CID 46277758.

- ^ Soĭfer, Valeriĭ. (1994). Lysenko and The Tragedy of Soviet Science. New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press. ISBN 9780813520872.

- ^ Wade, Nicholas (June 17, 2016). "The Scourge of Soviet Science". Wall Street Journal.

- ^ Swedin, Eric G. (2005). Science in the Contemporary World : An Encyclopedia. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. pp. 168, 280. ISBN 978-1851095247.

- ^ Alexandrov, Vladimir Yakovlevich (1993). Трудные годы советской биологии: Записки современника [Difficult Years of Soviet Biology: Notes by a Contemporary]. Наука ["Science"].

- ^ a b c Kolchinsky, Edouard I.; Kutschera, Ulrich; Hossfeld, Uwe; Levit, Georgy S. (2017). "Russia's new Lysenkoism". Current Biology. 27 (19): R1042–R1047. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2017.07.045. ISSN 0960-9822. PMID 29017033. which cites Graham, Loren (2016). Lysenko's Ghost: Epigenetics and Russia. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-08905-1.

- ^ Gordin, Michael D. (2012). "How Lysenkoism Became Pseudoscience: Dobzhansky to Velikovsky". Journal of the History of Biology. 45 (3): 443–468. doi:10.1007/s10739-011-9287-3. ISSN 0022-5010. JSTOR 41653570. PMID 21698424. S2CID 7541203.

- ^ Graham, Loren (2016). Lysenko's Ghost: Epigenetics and Russia. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-08905-1.

- ^ a b Gajewski W. (1990). "Lysenkoism in Poland". Quarterly Review of Biology. 65 (4): 423–34. doi:10.1086/416949. PMID 2082404. S2CID 85289413.

- ^ Orel, Vitezslav (1992). "Jaroslav Kříženecký (1896–1964), Tragic Victim of Lysenkoism in Czechoslovakia". Quarterly Review of Biology. 67 (4): 487–494. doi:10.1086/417797. JSTOR 2832019. S2CID 84243175.

- ^ Hagemann, Rudolf (2002). "How did East German genetics avoid Lysenkoism?". Trends in Genetics. 18 (6): 320–324. doi:10.1016/S0168-9525(02)02677-X. PMID 12044362.

- ^ a b c Li, C. C. (1987). "Lysenkoism in China". Journal of Heredity. 78 (5): 339. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.jhered.a110407.

- ^ Witkowski, J. A. (2007). "J. D. Bernal: The Sage of Science by Andrew Brown (2006), Oxford University Press". The FASEB Journal. 21 (2): 302–304. doi:10.1096/fj.07-0202ufm.

- ^ Goldsmith, Maurice (1980). Sage: A Life of J. D. Bernal. London: Hutchinson. pp. 105–108. ISBN 0-09-139550-X.

Further reading[edit]

- Denis Buican, L'éternel retour de Lyssenko, Paris, Copernic, 1978. ISBN 2859840192

- Ronald Fisher, "What Sort of Man is Lysenko?" Listener, 40 (1948): 874–875. Contemporary commentary by a British evolutionary biologist (pdf format)

- Loren Graham, Chapter 6. "Stalinist Ideology and the Lysenko Affair", in Science in Russia and the Soviet Union (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1993).

- Oren Solomon Harman, "C. D. Darlington and the British and American Reaction to Lysenko and the Soviet Conception of Science." Journal of the History of Biology, Vol. 36 No. 2 (New York: Springer, 2003)

- David Joravsky, The Lysenko Affair (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1970).

- Richard Levins and Richard Lewontin, "Lysenkoism", in The Dialectical Biologist (Boston: Harvard University Press, 1985).

- Anton Lang, "Michurin, Vavilov, and Lysenko". Science, Vol. 124 No. 3215, 1956) doi:10.1126/science.124.3215.277b

- Valery N. Soyfer, Lysenko and the Tragedy of Soviet Science (New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 1994). ISBN 0813520878

- "The Disastrous Effects of Lysenkoism on Soviet Agriculture". Science and Its Times, ed. Neil Schlager and Josh Lauer, Vol. 6. (Detroit: Gale, 2001)

External links[edit]

- SkepDic.com – 'Lysenkoism', The Skeptic's Dictionary

- Lysenkoism, BBC Radio 4 discussion with Robert Service, Steve Jones & Catherine Merridale (In Our Time, June 5, 2008)