The Virginia Constitutional Convention of 1829–1830 was a constitutional convention for the state of Virginia, held in Richmond from October 5, 1829 to January 15, 1830.

Background and composition[edit]

| History of Virginia |

|---|

|

|

Almost immediately, the Constitution of 1776 was recognized as flawed both for its restriction of the suffrage by property requirements, and for its malapportionment favoring the smaller eastern counties. Between 1801 and 1813, petitioners called on the Assembly to initiate a constitutional convention ten times. The House of Delegates passed a bill twice, but the conservative eastern planter majority in the Virginia Senate killed both measures. Continuing growth in the western parts of the state led to another fifteen years of agitation. Several counties in the Eastern Shore, northern Piedmont and western counties began opening polls for direct expression from the voters for a constitutional convention; eventually there were twenty-eight such counties calling for reform.[1]

Malapportionment in the Assembly was seen as "an usurpation of the minority over the majority" by the slave owning eastern aristocracy. Partisans argued for apportionment by white population, versus "federal numbers" combining white population with three-fifths slaves, versus the existing system counting whites and slaves equally to favor the slave-holding eastern counties. After several General Assembly sessions with close votes for calling a convention, in 1828 the Assembly allowed for a statewide ballot for "Convention", "Neutral" or "No Convention". It passed by 56.8 percent, with most convention support coming from west of the Blue Ridge Mountains northwest to the Ohio River. But the easterners in the State Senate had stacked the deck in their favor, by apportioning the delegates by four per Senate district, producing a group of men which was more wealthy and more conservative than the House of Delegates.[2]

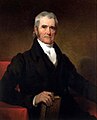

The last "gathering of giants"[3] from the Revolutionary generation included former presidents James Madison and James Monroe, and sitting Chief Justice John Marshall. But three generations were represented among those who would serve in public office including three presidents, seven U.S. Senators, fifteen U.S. Representatives and four governors. The other delegates to the Convention were sitting judges or members of the Virginia General Assembly.[4]

Meeting and debate[edit]

The Convention met from October 5, 1829 – January 15, 1830, and elected former president James Monroe of Loudoun its presiding officer. On December 8, Monroe withdrew due to failing health, and the Convention elected Philip P. Barbour as its new presiding officer. Barbour was a former Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives, a sitting federal district judge, and a future Justice on the Supreme Court. Conservatives among the Old Republicans such as John Randolph of Roanoke feared any change from the Founders' 1776 Constitution would lead to an ideological anarchy of "wild abstractions" imposed by egalitarian "French Jacobins" through "this maggot of innovation". In answer, John Marshall advanced his view with a petition from the freeholders of Richmond which observed that, "Virtue, intelligence, are not among the products of the soil. Attachment to [slave] property, often a sordid sentiment, is not to be confounded with the sacred flame of patriots." Any white male who had served in the War of 1812 or who would serve in the militia in there future defense of the country deserved the right to vote.[5]

Abel P. Upshur, a judge on the Virginia General Court, spoke for conservatives when he asserted that there "is a majority of interest as well as a majority in number". Because both persons and property were the "elements of society", majority rule by the people alone was not an equitable solution. "Those who have the greatest [property] stake in the Government…[must] have the greatest share of power in the administration of it." Lawyer John R. Cooke, a veteran of the War of 1812 countered that delegates must base the Constitution and legislative representation on the wishes of citizens, "the white population…[looking] to the people" for its authority, not only the wealthy, not to sectional slave-holding interests, and "not to the supposed rights of the [unequally populated] counties."[6]

Reformers' efforts to adopt direct popular election of the Governor were defeated in favor of continuing election by the General Assembly.[7] Thomas Jefferson Randolph, Thomas Jefferson's grandson, proposed gradual emancipation, a suggestion which never made it out of committee onto the Convention floor.[8] The reformers lost on almost every issue. Nevertheless, even with the exaggerated Virginia Senate representation apportioning the delegates in favor of the status quo, the three most important roll calls were close. The "white" population basis of apportioning the General Assembly failed by two votes. The extension of the vote to all free white males failed by two votes. When the popular election of governor passed on its first vote, it failed on reconsideration. The divisions which would lead to West Virginia's split were evident. Regardless of the various ideologies represented or delegate political affiliation, the final vote 55 for the proposed Constitution to 40 against was along an east-west divide. Only one delegate voted yes from west of the Blue Ridge Mountains.[9]

-

John Randolph

Conservative -

John Marshall

Reformer -

Abel P. Upshur

Conservative

Outcomes[edit]

Some malapportionment in the General Assembly was eased relative to the majority of voters and white population in the Valley in the House of Delegates, but nothing for the transmontane west. Some suffrage restrictions were modified to include long term leaseholders and male heads of household.[10] The Constitution of 1830 was a "triumph of traditionalism."[11]

Historical accounts of the convention often relay interpretations of Hugh B. Grigsby that emphasize it as the "last gathering of giants."[12] This approach typically omits names of the western reformers like Philip Doddridge who called for the convention in the first place. The "triumph of traditionalism" largely maintained traditional malapportionment preserving slaveowners’ disproportionate political power. This contributed to western Virginia counties’ later secession and formation of West Virginia led by Doddridge protégé Waitman T. Willey.

Delegates[edit]

The delegates to the Convention of were elected in May and June, 1829. Each of the 24 senatorial districts sent four delegates to the convention, for a total of 96 members. Three districts elected another delegate to replace a vacant seat.[13]

| District | Delegate | County | Current Office | Former Offices | Future Offices | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | John B. George | Tazewell | Assembly Delegate | |||

| Andrew McMilian | Lee | Assembly Delegate | ||||

| Edward Campbell | Washington | |||||

| William Byars | Washington | Assembly Delegate | ||||

| 2 | Gordon Cloyd | Montgomery | ||||

| Henley Chapman | Giles | Assembly Senator | ||||

| John P. Mathews | Wythe | |||||

| William Oglesby | Grayson | Assembly Delegate | ||||

| 3 | George Townes | Cheserfield | Assembly Senator | |||

| Benjamin W. S. Cabell | Pittsylvania | Assembly Senator | ||||

| Joseph Martin | Henry | Assembly Senator | ||||

| Archibald Stuart | Patrick | U.S. Representative | ||||

| 4 | John Randolph | Charlotte | U.S. Senator; U.S. Representative | |||

| William Leigh | Halifax | Judge of the Virginia General Court | ||||

| Richard Logan | Halifax | Assembly Senator | ||||

| Richard N. Venable | Prince Edward | President of the Upper Appomattox Canal Co. | ||||

| 5 | William Henry Brodnax | Dinwiddie | Brigadier General, Virginia Militia | |||

| George C. Groomgoole | Brunswick | |||||

| Mark Alexander | Mecklenburg | U.S. Representative | ||||

| William O. Goode | Mechlenburg | U.S. Representative | ||||

| 6 | John Y. Mason | Southampton | U.S. Representative, U.S. District Judge, Secretary of State, Secretary of the Navy | |||

| James Trezvant | Southampton | U.S. Representative | ||||

| Augustine Claiborne | Greensville | Virginia Delegate | ||||

| John Urquhart | Southampton | |||||

| 7 | Littleton W. Tazewell | Norfolk Borough | U.S. Senator | Governor of Virginia | ||

| Joseph Prentis | Nansemond | |||||

| Robert B. Taylor | Norfolk Borough | Resigned | ||||

| Hugh Blair Grigsby[1] | Norfolk Borough | Assembly Delegate | ||||

| 8 | George Loyall | Norfolk Borough | U.S. Representative | |||

| Thomas R. Joynes | Accomack | Assembly Delegate | ||||

| Thomas M. Bayly | Accomack | U.S. Representative | ||||

| Calvin H. Read | Northampton | Assembly Delegate | Died | |||

| 9 | Abel P. Upshur | Northampton | Justice of the Virginia General Court | Secretary of the Navy; Secretary of State | ||

| John Marshall | Richmond City | U.S. Chief Justice | ||||

| John Tyler | Charles City | U.S. Senator | President of the U.S. | |||

| Philip N. Nicholas | Richmond City | Judge of the Virginia General Court | ||||

| 10 | John B. Clopton | New Kent | Assembly Senator | Judge of the Virginia General Court and Circuit Court | ||

| John Winston Jones | Chesterfield | U.S. Representative | ||||

| Benjamin W. Leigh | Chesterfield | U.S. Senator | ||||

| Samuel Taylor | Chesterfield | Assembly Senator | ||||

| 11 | William B. Giles | Amelia | Governor | |||

| William Campbell | Bedford | Assembly Senator | ||||

| Samuel Claytor | Campbell | |||||

| Callowhill Mennis | Bedford | Resigned | ||||

| James Saunders | Campbell | Assembly Senator | ||||

| 12 | Andrew Beirne | Monroe | U.S. Representative | |||

| William Smith | Greenbrier | U.S. Representative | ||||

| Fleming B. Miller | Botetourt | Assembly Senator | ||||

| John Baxter | Pocahontas | Assembly Senator | ||||

| 13 | Edwin S. Duncan | Harrison | Assembly Senator | |||

| John Laidley | Cabell | Assembly Delegate | ||||

| Lewis Summers | Kanawha | Assembly Delegate | ||||

| Adam See | Randolph | Assembly Delegate | ||||

| 14 | Philip Doddridge | Brooke | U.S. Representative | |||

| Charles S. Morgan | Monongalia | Assembly Senator | ||||

| Alexander Campbell | Brooke | Ordained minister, leader of the Disciples of Christ | Founder and president of Bethany College | |||

| Eugenius M. Wilson | Monongalia | |||||

| 15 | Briscoe G. Baldwin | Augusta | Major General, Virginia Militia | Justice of the Virginia Supreme Court | ||

| Chapman Johnson | Augusta | Assembly Senator | ||||

| William McCoy | Pendleton | U.S. Representative | ||||

| Samuel M. Moore | Rockbridge | U.S. Representative | ||||

| 16 | James Pleasants | Goochland | U.S. Senator; Governor of Virginia | |||

| William F. Gordon | Albemarle | U.S. Representative | ||||

| Lucas P. Thompson | Amherst | Assembly Delegate | ||||

| Thomas Massie, Jr. | Nelson | Assembly Delegate | ||||

| 17 | James Madison | Orange | President of the U.S. | |||

| Philip P. Barbour | Orange | U.S. District Judge | Speaker of the House | Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court | Elected Presiding Officer after Monroe resigned the office | |

| David Watson | Louisa | Assembly Delegate | Died without attending | |||

| Robert Stanard | Spotsylvania | Virginia Justice | ||||

| 18 | John Roane | King William | U.S. Representative | |||

| William P. Taylor | Caroline | U.S. Representative | ||||

| Richard Morris | Hanover | Assembly Delegate | ||||

| James M. Garnett | Essex | U.S. Representative | ||||

| William A. G. Dade | Prince William | Assembly Senator | Died | |||

| 19 | Ellyson Currie | Lancaster | Assembly Senator | |||

| John Taliaferro | King George | U.S. Representative | ||||

| Fleming Bates | Northumberland | |||||

| John S. Barbour | Culpeper | U.S. Representative | ||||

| John Scott | Fauquier | Assembly Senator | ||||

| 20 | John Macrae | Fauquier | Assembly Delegate | (1829 session) | ||

| Thomas Marshall | Fauquier | Assembly Delegate | (1830 session) | |||

| John W. Green | Culpeper | Virginia Justice | ||||

| Peachy Harrison | Rockingham | Assembly Senator | ||||

| 21 | Jacob Williamson | Rockingham | ||||

| William Anderson | Shenandoah | Assembly Delegate | ||||

| Samuel Coffman | Shenandoah | |||||

| William Naylor | Hampshire | Assembly Delegate | ||||

| 22 | William Donaldson | Hampshire | Assembly Senator | |||

| Elisha Boyd | Berkeley | Assembly Delegate | Brigadier General, Virginia Militia | Assembly Senator | ||

| Philip Pendleton | Berkeley | U.S. Judge | ||||

| John R. Cocke | Frederick | |||||

| 23 | Alfred H. Powell | Frederick | U.S. Representative | |||

| Hierome L. Opie | Jefferson | Resigned | ||||

| James M. Mason | Jefferson | U.S. Senator | ||||

| Thomas Griggs, Jr. | Jefferson | Assembly Delegate | ||||

| 24 | James Monroe | Loudoun | President of the U.S. | First Presiding Officer | ||

| Charles F. Mercer | Loudoun | U.S. Representative | ||||

| William H. Fitzhugh | Fairfax | Assembly Senator | ||||

| Richard H. Henderson | Loudoun |

Districts[edit]

Districts are numbered as follows for the table and map:

- Washington, Lee, Scott, Russell and Tazewell

- Wythe, Montgomery, Grayson and Giles

- Franklin, Patrick, Henry and Pittsylvania

- Charlotte, Halifax, and Prince Edward

- Brunswick, Dinwiddie, Lunenburg, and Mecklenburg

- Sussex, Surry, Southampton, Isle of Wight, Prince George, Greensville

- Norfolk, Princess Anne, Nansemond and Borough of Norfolk

- Mathews, Middlesex, Accomack, Northampton and Gloucester

- City of Williamsburg, Charles City, Elizabeth City, James City, City of Richmond, Henrico, New Kent, Warwick and York

- Amelia, Chesterfield, Cumberland, Nottoway, Powhatan and Town of Petersburg

- Campbell, Buckingham and Bedford

- Monroe, Greenbriar, Bath, Botetourt, Alleghany, Pocahontas, Nicholas

- Kanawha, Mason, Cabell, Randolph, Harrison, Lewis, Wood and Logan

- Ohio, Tyler, Brooke, Monongalia and Preston

- Augusta, Rockbridge, Pendleton

- Albemarle, Amherst, Nelson, Fluvanna and Goochland

- Spotsylvania, Louisa, Orange, and Madison

- King William, King and Queen, Essex, Caroline and Hanover

- King George, Westmoreland, Lancaster, Northumberland, Richmond, Stafford and Prince William

- Fauquier and Culpeper

- Shenandoah and Rockingham

- Hampshire, Hardy, Berkeley and Morgan

- Frederick and Jefferson

- Loudoun and Fairfax

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Shade 1996, p. 57–61

- ^ Shade 1996, p. 62–64

- ^ Gutzman 2007, p. 163, 165

- ^ Gutzman 2007, p. 163, 165

- ^ Shade 1996, pp. 65–66

- ^ Shade 1996, pp. 65

- ^ Gutzman 2007, p. 188

- ^ Andrews 1937, p. 430

- ^ Heinemann 2007, p. 173–174

- ^ Shade 1996, p. 64

- ^ Heinemann 2007, p. 173

- ^ Richards, Samuel J. (Fall 2019). "Reclaiming Congressman Philip Doddridge from Tidewater Cultural Imperialism". West Virginia History: A Journal of Regional Studies. 13 (1): 4–5. doi:10.1353/wvh.2019.0019. S2CID 211648744.

- ^ Pulliam 1901, p. 67, 70–72

Bibliography[edit]

- Andrews, Matthew Page (1937). Virginia, the Old Dominion. Doubleday, Doran & Company. ASIN B0006E942K.

- Gutzman, Kevin R.C. (2007). Virginia's American Revolution: from Dominion to Republic, 1776-1840. Lexington Books. ISBN 978-0-7391-2131-3.

- Heinemann, Ronald L. (2008). Old Dominion, New Commonwealth: a history of Virginia, 1607-2007. University of Virginia Press. ISBN 978-0-8139-2769-5.

- Pulliam, David Loyd (1901). The Constitutional Conventions of Virginia from the foundation of the Commonwealth to the present time. John T. West, Richmond. ISBN 978-1-2879-2059-5.

- Richards, Samuel J. (Fall 2019). "Reclaiming Congressman Philip Doddridge from Tidewater Cultural Imperialism". West Virginia History: A Journal of Regional Studies. 13 (2): 1–26. doi:10.1353/wvh.2019.0019. S2CID 211648744.

- Shade, William G. (1996). Democratizing the Old Dominion: Virginia and the Second Party System, 1824–1861. University of Virginia Press. ISBN 978-0-8139-1654-5.

External links[edit]

- Proceedings and Debates of the Virginia State Convention of 1829–30. Samuel Shepherd & Co. for Ritchie & Cook 1830 Richmond online from the archives of the University of Virginia at archive.org