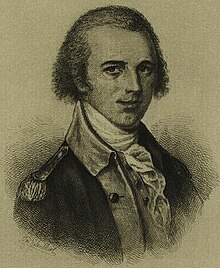

Uriah Forrest | |

|---|---|

| |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Maryland's 3rd district | |

| In office March 4, 1793 – November 8, 1794 | |

| Preceded by | John F. Mercer |

| Succeeded by | Benjamin Edwards |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 1756 St. Mary's County, Province of Maryland, British America |

| Died | July 6, 1805 (aged 48–49) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Resting place | Oak Hill Cemetery Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Political party | Federalist |

| Spouse | Rebecca Plater |

| Residence | Georgetown |

| Occupation | Tobacco trader, gentleman |

| Signature | |

Uriah Forrest (1756 – July 6, 1805) was an American statesman and military leader from Maryland. Forrest was born in St. Mary's County in the Province of Maryland, near Leonardtown.[1][2] In his early childhood, he received only limited schooling. Born into a family with three other brothers, he was the direct descendant of a person who came to Jamestown, Virginia, in 1608.[3][4][5]

Revolutionary War[edit]

He served in varying roles within the Maryland Line.[6][1] From January 14, 1776, until July 1776 he served as a 1st lieutenant in John Gunby's Independent Maryland Company. When this ended, he became a captain in the 3rd Battalion of the Maryland Flying Camp, until December 1776 when he was promoted to major and transferred to the 3rd Maryland Regiment.[7][8] As a result of the change of military positions, he did not fight at the Battle of Brooklyn, unlike the 1st Maryland Regiment commanded by William Smallwood ("Smallwood's Battalion") and other military units, which fought under the command of General George Washington. By April 1777, his unit changed yet again when he was promoted to lieutenant colonel, and he served in "Smallwood's Battalion" until August 1779. He was injured at the Battle of Germantown where he lost a limb.[9][10]

In August 1779, he left Smallwood's unit and served as a Lieutenant Colonel as part of the 7th Maryland Regiment.[11][12] He retained that position until February 23, 1781, when he resigned.

During his military service, he fought to defend St. George's Island, in Saint Mary's County, in July 1776 and at other major battles throughout the war, such as the Battle of Brandywine. He served in varied regiments before he resigned as Auditor General within the Continental Army on February 19, 1781.[3][13][14]

State politics[edit]

In 1780, a bill was passed by both houses of the Maryland General Assembly concerning the confiscation of Loyalist property in the state.[15] Forrest was one of the three commissioners, the others being William Paca and Clement Hollyday, to confiscate holdings of such property, which was later apportioned out and sold to certain individuals. He was qualified for that position in February 1781 and resigned by July.[16]

After the war, he traveled to London from St. Mary's County and stayed until 1786, when he returned to Georgetown.[5] He returned to Maryland in 1783 to establish a tobacco export business in Georgetown, with business partners Benjamin Stoddert and John Murdock and then returned to London. He was the "resident partner of Forrest, Stoddert & Murdock" [9][5]

In 1784, Forrest was admitted as an original member of The Society of the Cincinnati of Maryland.[17][18] When he learned of its founding, he said:

I cannot express my feelings on reading today, for the first Time, the constitution of the Society of the Cincinnati... though, separated by an Ocean of 3000 Miles, and a slave to Business; there is not one among you, who feel more Affection, for that brave handful, who persevered to the last, than I do.

Forrest was elected to the Maryland State House of Delegates in numerous terms and served from 1781 to 1783, 1786 to 1787, and 1787 to 1790, as a member of the Maryland State Senate from 1796 to 1800, and a State Court Judge from 1799 to 1800.[16]

He represented St. Mary's County in most of the 1780s and then Montgomery County and in the Maryland Senate represented the Western Shore of Maryland.

He also served as churchwarden of St. Andrew's Parish within St. Mary's County (1782-1783), justice in Montgomery County (1799-1800). He owned five black slaves in 1790, which had increased to nine by 1801.[16] In 1800, he had a bounty land warrant for his military service. However, he never occupied the land, which remained vacant.[19]

Federal politics[edit]

Forrest was also active in politics by representing Maryland as a delegate to the Continental Congress in 1787.[1] Thomas Jefferson would tell him in a letter from Paris on December 31 that he admired the framers of the Constitution but also was concerned about them sowing the "seeds of danger" by thinking that rulers after them would be "as honest as themselves."[20][21][22]

Forrest would be nominated to be a US senator the following year.[23] All of the people nominated would be Federalists, as he was, he lost to Charles Carroll in the second and third ballot voting by a few votes.[24][25][26]

In 1792, he ran for US House of Representatives within the third district of Maryland as a "Pro-Administration candidate."[1][13] The Federalist won against the Anti-Federalist William Dorsey, by 669 votes, with most of his votes coming from individuals within Montgomery County, Maryland, and almost 100 more from Frederick County, Maryland, counties that made up parts of the Third District.[27] He would serve as a representative from March 1793 to November 1794, when he resigned. During his time in office, he missed 79.6% of the roll call votes, which is "much worse than the median of 13.0% among the lifetime records of representatives serving in Jun 1794."[28]

He stayed a "friend and host to George Washington," cementing his role in the Federalist Party and national politics.[29][30][31] However, he still hosted Thomas Jefferson, later a Democratic-Republican, for a dinner in 1790 on his trip to see "the Little Falls of the Potomac River."[32][33]

In 1795, Forrest was commissioned a brigadier general of Maryland Militia's Fourth Brigade in 1795 and major general of the Maryland Militia's First Division from 1795 to 1801.[1][16] That failed to end his involvement in national politics. In December 1797, he wrote to James McHenry and remarked on his successful efforts to get James Lloyd elected to the US Senate, which filled a vacancy that had been left by John Henry's resignation.[34]

Involvement in founding of Washington, DC[edit]

On October 13, 1790, he would be one of the "original proprietors" of land that was taken for the Washington City.[35] Taking the suggestions of leading Georgetown merchants, suggesting that the "proposed Federal City be on the land opposite Georgetown across Rock Creek" since Georgetown was already a port. Forrest, would sign a document[36][37] saying the following:

We the subscribers, do hereby agree... to sell and make over by sufficient Deeds, in any manner which shall be directed by General Washington, or any person acting under him, and on such terms as he shall determine to be reasonable and just; and of the Lands which we possess in the vicinity of Georgetown, for the uses of the Federal City, provided the same shall be erected in the said vicinity.

As the historical writer Bob Arnebeck wrote, Forrest would be a major landholder who would buy up land in the area, which would be sold to another speculator, James Greenleaf, and ultimately the federal government.[38][39] All of the speculators, including Benjamin Stoddert, Robert Morris, and John Nicholson, would make out handsomely from that agreement, with some conspiring with Forrest against other landholders. Ultimately, 15 landowners would negotiate with Washington to "give the government land for the creation of a new federal capital, Washington," and in 1792, Forrest and James Williams would buy land that would become the National Mall from the State of Maryland and then sell it to the federal government.[40]

Later, in 1791, Forrest would serve served as mayor of the Town of George, now Georgetown, when George Washington met with local landowners at his home to negotiate purchase of the land needed to build the new capital city.[41][42][43] The meeting, on March 29, would be attended by landowners of Georgetown, Carollsburg, and others like Washington, agreeing to sell "half of their land within the newly designated 10-mile-square Federal District thus creating a new capital city for the United States of America," and Pierre L'Enfant later laid out the plan for Washington City.

In 1796, Ninian Beall would sell a "bluff overlooking the new capital to one Peter Casanave," who would sell it in two months to Uriah Forrest, "who sold it the next year to Isaac Pollock."[44][45] The latter would then "traded it to the over-leveraged Samuel Jackson," and then Joseph Nourse, Register of the US Treasury under six presidential administrations would repurpose the "modest dwelling as one of two symmetrical wings on a new Federal Palladian mansion, which he called Bellevue." Also, Forrest would be instrumental in incorporation of "the Georgetown Bridge Company, the Bank of Columbia, and the Georgetown Mutual Insurance Company."[5][16]

Personal life[edit]

On October 11, 1789, at 43, Forrest married Rebecca Plater, of a well-off family deeply involved in State politics, who was born at Sotterley Plantation.[3][46] They would have seven children.[47]

Later life[edit]

By 1790, the Forrest family was living next to Benjamin Stoddert, a friend of Forrest, a fellow business partner and Southern Marylander. [3] In 1794 Forrest would build a home near Washington, D.C., called Rosedale. It would be closely resembling the architectural style of Mount Vernon, surrounded by stone buildings that had been constructed in the 1740s.[48][49]

The large-frame house would be located in the Northwest quadrant of Washington, DC.[50] In later years, it would be considered "to be the oldest home in Washington". The home would become for the Forrest family a respite for Rebecca and their children "from the bustling port city life of Georgetown" and remove them from "impending war."[46] Throughout the years, the house and its grounds would serve as a "center for political discussions and social entertaining" with the hosting of "a large dinner party for President John Adams" in 1800. Overall, Forrest would exchange numerous letters to Washington, Jefferson, Adams, Benjamin Franklin, and Alexander Hamilton between 1780 and 1804.[51]

In 1796, Forrest would mortgage "Rosedale" to obtain loans from the state of Maryland to boost the district's economy, but by 1802, he would be led into bankruptcy, with Philip Barton Key, his brother-in-law, accepting the mortgage.[3][46] Key then granted Forrest lifetime use of the property. Forrest also served in a local governmental position in his late life. From 1800 until his death in 1805, he would serve as the clerk of the District of Columbia's circuit court.[1][52]

Forrest died on July 6, 1805, in the parlor of the Rosedale's farmhouse and was buried in the Presbyterian Burying Ground in Washington, D.C.[53][54][1][46][13] His remains were later disinterred, and he was reburied at Oak Hill Cemetery.[53][1]

At the time of his death, Forrest owned, as noted by now-retired State Archivist for the Maryland State Archives, Edward C. Papenfuse, about "1,680 acres in Allegany, St. Mary's, and Montgomery counties, and the District of Columbia, plus ca. 150 lots in the District of Columbia."[16][55][56][57][58][59][60]

Legacy[edit]

His estate was "still plagued with debt" after his death and was almost lost "to debts and litigation" but kept in the family for many years to come.[3][16]

Before her death on September 5, 1843, at "Rosedale," Rebecca would file for a widow's pension from the federal government for her husband's military service. In her September 1838 filing, she would be described as a resident of Georgetown who married Forrest in 1789 and it says that he had fought in the Battle of Brandywine.[61] Apart from the pension money granted to Rebecca, $600 per year, his descendants many years later would pursue the same records and wanted to know about Forrest's military career. The pension papers of Rebeca would later become the "Rebecca Forrest (the widow of Uriah Forrest) Papers, 1838-1843," held at the Historical Society of Washington D.C.[62]

In the early 19th century, his home overlooking the Potomac River, in which Forrest lived approximately from 1790 to 1794 would become the home of William Marbury, who is known by the Marbury v. Madison Supreme Court case.[63] In December 1992, it would become the Embassy of the Ukraine, in Washington, D.C.

Later, his granddaughter, Alice Green, also lived at Rosedale.[64] She would marry Don Angel Maria de Iturbide y Huarte, an "exiled prince of the Mexican imperial line and a student at Georgetown University," and have a son named Don Agustín, Prince of Iturbide, the heir of Emperor Maximilian I of Mexico and prince of the First and Second Mexican Empires, making Forrest his great-grandfather. His estate would become the Rosedale Conservancy.[65][66]

Recently, proponents of District of Columbia voting rights have cited Forrest's representation of Maryland in the US House of Representatives because he lived within the borders of Washington, D.C.[67][68][69]

In 2010, C.M. Mayo would write a novel of historical fiction, The Last Prince of the Mexican Empire, which was based upon the "true story of half-American toddler Agustín de Iturbide y Green, a great-grandson of Maryland's former governor George Plater and grandson of revolutionary war hero General Uriah Forrest."[70]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h FORREST, Uriah, (1756 - 1805), Biographical Directory of the United States Congress, 1774-Present, US Congress. Accessed May 28, 2017.

- ^ Crocker Farm, Inc., Uriah Forrest (Maryland Revolutionary War Hero and Politician) Hand-Written Note and Print, 2012. Accessed May 28, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f Linda Reno and Greg White, "From Obscurity to Greatness, the Story of Uriah Forrest", St. Mary's Families, June 13, 2004.

- ^ He also is a direct male descendant of Thomas Forrest, Esq, a financier with the Virginia Company who came to the Jamestown colony on the Second Supply ship in 1608.

- ^ a b c d A Biographical Dictionary of the Maryland Legislature 1635-1789 by Edward C. Papenfuse, et al., Archives of Maryland Online, Vol. 426, 324.

- ^ Francis Bernard Heitman, Historical Register of Officers of the Continental Army During the War of the Revolution, April 1775, to December 1783 (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Co., 1982), 30-32, 233.

- ^ Muster Rolls and Other Records of Service of Maryland Troops in the American Revolution, Archives of Maryland Online, Vol. 18, 30.

- ^ Officers of the Flying Camp elected, Committee to examine the Accounts of the Supervisors of Saltpetre Works Resolution empowering the Council of Safety to contract for building a Powder-Mill on the publick account, repealed, American Archives, v6:1491.

- ^ a b Ecker (1933), p. 12

- ^ Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty-Land-Warrant Application Files. National Archives and Records Administration, retrieved February 22, 2022.

- ^ Heitman, Historical Register of Officers of the Continental Army,30-31.

- ^ Journal and Correspondence of the Council of Maryland, 1779-1780, Archives of Maryland Online, Vol. 43, 35.

- ^ a b c FORREST, Uriah, U.S. House of Representatives Office of the Historian, accessed May 28, 2017.

- ^ A Proud Place in American History, Island Inn and Suites, 2012.

- ^ Joan Grattan, Documents of Confiscations of Loyalists' Holdings (1787-1801), The Johns Hopkins University, 2005.

- ^ a b c d e f g Biographical Dictionary of the Maryland Legislature 1635-1789 by Edward C. Papenfuse, et al., Archives of Maryland Online, Vol. 426, 325.

- ^ Metcalf, Bryce (1938). Original Members and Other Officers Eligible to the Society of the Cincinnati, 1783–1938: With the Institution, Rules of Admission, and Lists of the Officers of the General and State Societies Strasburg, VA: Shenandoah Publishing House, Inc., p. 129.

- ^ Society of Cincinnati, "Maryland in the American Revolution, 2009. Accessed May 28, 2017.

- ^ Uriah Forrest, Warrant Number 756, 1800, U.S. Revolutionary War Bounty Land Warrants Used in the U.S. Military District of Ohio and Relating Papers (Acts of 1788, 1803, and 1806), 1788-1806, National Archives, NARA M829, Records of the Bureau of Land Management, Record Group 49, Courtesy of Ancestry.com.

- ^ Letter to Uriah Forrest, December 31, 1787, The Trustees of Princeton University, 2013.

- ^ Delegate Discussions: Bill of Rights, The President and Fellows of Harvard College, 2017.

- ^ "From Thomas Jefferson to Uriah Forrest, with Enclosure, 31 December 1787," Founders Online, National Archives, last modified March 30, 2017.

- ^ Maryland 1788 U.S. Senate, Ballot 2, Lampi Collection of American Electoral Returns, 1788-1825. -- American Antiquarian Society, 2007, accessed May 28, 2017.

- ^ Maryland 1788 U.S. Senate, Ballot 3, Lampi Collection of American Electoral Returns, 1788-1825. -- American Antiquarian Society, 2007, accessed May 28, 2017.

- ^ Maryland 1788 U.S. Senate, Lampi Collection of American Electoral Returns, 1788-1825. -- American Antiquarian Society, 2007, accessed May 28, 2017.

- ^ Maryland 1788 U.S. Senate, Ballot 2, Lampi Collection of American Electoral Returns, 1788-1825. -- American Antiquarian Society, 2007, accessed May 28, 2017.

- ^ Maryland 1792 U.S. House of Representatives, District 3, Lampi Collection of American Electoral Returns, 1788-1825. -- American Antiquarian Society, 2007, accessed May 28, 2017.

- ^ GovTrack, Rep. Uriah Forrest: Former Representative from Maryland's 3rd District, Civic Impulse, LLC. Accessed May 28, 2017.

- ^ Winthrop Faulkner, 1978 Win Faulkner House in Cleveland Park – $3.85 Million, Modern Capital DC, January 24, 2013.

- ^ "From George Washington to Uriah Forrest, 20 January 1793," Founders Online, National Archives, last modified March 30, 2017.

- ^ Larry Luxner, Ambassador Valeriy Chaly: Ukraine Still in ‘State of War’, The Washington Diplomat, October 29, 2015.

- ^ Thomas Jefferson Foundation, Thomas Jefferson Encyclopedia: Washington, D.C., 2015. Accessed May 28, 2017.

- ^ Thomas Jefferson to Uriah Forrest, June 13, 1790, Library of Congress, series: Series 1: General Correspondence. 1651-1827, Microfilm Reel: 012, The Thomas Jefferson Papers at the Library of Congress.

- ^ Uriah Forrest to James McHenry, On the election of James Lloyd to the U.S. Senate, December 8, 1797, Papers of the War Department 1794-1800, accessed May 28, 2017.

- ^ [Historic-Structures, "Brickyard Hill House, Washington DC," October 26, 2010.

- ^ Bob Arnebeck, Seat of Empire: the General and the Plan 1790 to 1801, January 2, 2017. Arnebeck's post is a summary of his book, Through a Fiery Trial: Building Washington, 1790-1800.

- ^ H.P. Caemmerer, Washington: The National Capital (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1932), 19, 21.

- ^ Bob Arnebeck, Tracking the Speculators, 2010. Accessed May 28, 2017.

- ^ Greenleaf v. Birth 34 U.S. 292 (1835), Justia, 2017.

- ^ Original Proprietors of the National Mall's Land, Histories of the National Mall, accessed May 28, 2017.

- ^ Forrest Marbury House, The Historical Markers Database, 2013.

- ^ Historic American Buildings Survey, Forrest-Marbury House, 3350 M Street Northwest, Washington, District of Columbia, DC, Library of Congress, Documentation compiled after 1933, HABS DC,GEO,55-.

- ^ Uriah Forrest, Mayor of Georgetown to William Thornton, Alexander White, and Tristam Dalton, Commissioners, March 28, 1801, Library of Congress, Microfilm Reel: 057, series: Series 3: District of Columbia Miscellany. 1790-1808, The Thomas Jefferson Papers at the Library of Congress.

- ^ John Foreman, BIG OLD HOUSES: Not So Big, but Really Old, New York Social Diary, 2014.

- ^ Chronology, The National Society of The Colonial Dames of America, 2015.

- ^ a b c d Rosedale's History, The Rosedale Conservancy, 2017. Accessed May 28, 2017.

- ^ They would be named Ann "Nancy" Forrest (1790-1870), George Plater Forrest (1794-1843), Henry Forrest, Eliza Forrest, Maria Forrest (1799-1869), Benjamin Stoddert Forrest (d. 1840), and Uriah Forrest, Jr.

- ^ Carol B. Thompson (State Preservation Officer, National Park Service's "National Register of Historic Places Registration Form: Cleveland Park District," DC Office of Planning, April 27, 1987. See pages 6-7 of this PDF.

- ^ Fritz Hahn and Harrison Smith, No hiking boots required: 6 great city strolls in Washington, Washington Post, May 11, 2017.

- ^ Kathleen Eder Group, Cleveland Park, 2017.

- ^ See the following as examples of such contact: "Extract from John Adams to Uriah Forrest," June 20, 1797, "To George Washington from Uriah Forrest, 7 April 1780," "To George Washington from Uriah Forrest, 17 August 1780," "To Thomas Jefferson from Uriah Forrest, 8 October 1784," "To Thomas Jefferson from Uriah Forrest, 20 January 1787," "To Thomas Jefferson from Uriah Forrest, 11 December 1787," "[To Thomas Jefferson from Uriah Forrest, 18 December 1787]," "To John Adams from Uriah Forrest, 10 January 1788," "To George Washington from Uriah Forrest, 27 April 1791," "To George Washington from Uriah Forrest, 14 June 1791 [letter not found]," "To Thomas Jefferson from Uriah Forrest, 19 October 1791," "To Alexander Hamilton from Uriah Forrest, 7 November 1792," "To George Washington from Uriah Forrest, 10 January 1793," "To George Washington from Uriah Forrest, 11 February 1794," "To John Adams from Uriah Forrest, 23 June 1797," "To John Adams from Uriah Forrest, 28 April 1799," "To John Adams from Uriah Forrest, 25 January 1800," "To John Adams from Uriah Forrest, 4 June 1800," "To Thomas Jefferson from Uriah Forrest, 11 August 1804," "To Thomas Jefferson from Uriah Forrest, 17 August 1804," Letter from Uriah Forrest to Benjamin Franklin, Apr. 10, 1784.

- ^ Hilary Russell, The Operation of the Underground Railroad in Washington, D.C., c. 1800–1860, National Park Service, July 2001.

- ^ a b Proctor, John Clagett (October 4, 1942). "Georgetown's Most Historic Cemetery". The Sunday Star. p. 31.

- ^ Heitman, Historical Register of Officers of the Continental Army, 233.

- ^ Dr. Edward C. Papenfuse, Maryland State Archivist and Commissioner of Land Patents, Maryland State Archives.

- ^ Edward Papenfuse, Adjunct Faculty, Johns Hopkins University, 2017.

- ^ Ed Papenfuse: Digital Preservation Pioneer, Library of Congress blog, February 2011.

- ^ Dr. Edward C. Papenfuse, University of Maryland Francis King Carey School of Law, 2017.

- ^ Michael Dresser, Papenfuse ends 38-year run as Maryland's memory keeper, Baltimore Sun, November 4, 2013.

- ^ Edward Papenfuse: Maryland State Archivist and Commissioner (Rt), Jefferson Institute, 2017.

- ^ Rebecca Forrest, Widow's Pension Application File, W. 24,225, 1838, Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty-Land Warrant Application Files, National Archives, NARA M804, Records of the Department of Veterans Affairs, Record Group 15. Courtesy of Ancestry.com.

- ^ Historical Society of Washington D.C, Selected Original Proprietors Resources Available at the Kiplinger Research Library, accessed May 28, 2017.

- ^ Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Ukraine, History of the Embassy of Ukraine in USA, 2012. Accessed May 28, 2017.

- ^ Claudia Swain, Georgetown University's Imperial Prince, WETA, April 5, 2015.

- ^ Why Is It Named Cleveland Park?, Ghosts of DC, March 3, 2015.

- ^ DC Preservation League, Rosedale (Uriah Forrest House), 2017.

- ^ David Wheeler, Treat Washington, DC as Part of Maryland for Congressional Elections, April 22, 2004.

- ^ D.C. Vote, Emphasizing Events Important to the DC Voting Representation Movement, 2007.

- ^ Cityhood for DC, A Real Plan for DC Voting Rights and Home Rule, 2017.

- ^ College of Southern Maryland, "CSM Connections Welcomes Author C.M. Mayo Oct. 15 in Leonardtown", Southern Maryland Online, October 15, 2010.

Sources[edit]

- Ecker, Grace Dunlop (1933). A Portrait of Old Georgetown. Garrett & Massie, Inc.