The Stop Our Ship (SOS) movement, a component of the overall civilian and GI movements against the Vietnam War, was directed towards and developed on board U.S. Navy ships, particularly aircraft carriers heading to Southeast Asia.[1] It was concentrated on and around major U.S. Naval stations and ships on the West Coast from mid-1970 to the end of the Vietnam War in 1975, and at its height involved tens of thousands of antiwar civilians, military personnel and veterans. It was sparked by the tactical shift of U.S. combat operations in Southeast Asia from the ground to the air. As the ground war stalemated and Army grunts increasingly refused to fight or resisted the war in various other ways, the U.S. “turned increasingly to air bombardment”.[1][2] By 1972 there were twice as many Seventh Fleet aircraft carriers in the Gulf of Tonkin as previously and the antiwar movement, which was at its height in the U.S. and worldwide, became a significant factor in the Navy. While no ships were actually prevented from returning to war, the campaigns, combined with the broad antiwar and rebellious sentiment of the times, stirred up substantial difficulties for the Navy, including active duty sailors refusing to sail with their ships, circulating petitions and antiwar propaganda on board, disobeying orders, and committing sabotage, as well as persistent civilian antiwar activity in support of dissident sailors. Several ship combat missions were postponed or altered and one ship was delayed by a combination of a civilian blockade and crewmen jumping overboard.[3]: 112–113, 115–116 [4][5]

The major targets of the SOS movement were four different aircraft carriers, the USS Constellation, the USS Coral Sea, the USS Kitty Hawk and the USS Enterprise, with lesser but significant activity on and around a number of other ships.

USS Constellation[edit]

The first effort began in 1970 in San Diego, the principal homeport of the U.S. Navy's Pacific Fleet.[6] A San Diego-based antiwar group, Nonviolent Action, founded by peace activist Francesco Da Vinci,[7] came up with the idea of the Constellation Project, sometimes called The Harbor Project (the SOS name developed later). It was a nonviolent campaign to oppose the war and, at the same time, to show support for the crew of the USS Constellation. Through leaflets and letters, NVA told the sailors that they were not against them, they were only against their orders. NVA's nonviolent campaign attracted other peace groups such as the Concerned Officers Movement and the Peoples Union. As press coverage of the Constellation Project expanded, it drew the attention of antiwar activists from all over California, including Joan Baez and David Harris.[8] At that point, David Harris suggested expanding the Constellation Project into a Constellation Vote – a citywide referendum asking San Diegans to vote on whether the USS Constellation should be redeployed to Vietnam or stay home for peace. The Constellation Vote set the spark for the larger SOS movement to come.[9][1][10]

Constellation Vote[edit]

Although the city-wide Constellation Vote was non-binding, it served as a dramatic exercise in democracy. It gave not only San Diego citizens a voice in regard to being for or against the carrier's return to Southeast Asia, it also gave sailors a chance to vote. In preparation of the Constellation Vote, hundreds of activists, including sailors and veterans, canvassed the city. The canvassing was followed by a citywide straw vote from September 17 through September 21, 1971. Out of 54,721 votes counted, over 82% of voters elected to keep the ship home, including 73% of the military personnel who voted. While not a "real" vote, the impact on public opinion was appreciable, boosted by national prime time coverage by CBS and ABC television.[11][12][13][14][15] In Congressional hearings in December 1972 Admiral David H.Bagley, the U.S. Navy's Chief of Naval Personnel testified that "considerable public interest was generated" by the campaign.[16]

Antiwar military personnel[edit]

The involvement of large numbers of antiwar officers and enlisted men created significant debate in the traditionally pro-military town. It also permitted creative methods not normally available to other antiwar groups, such as the CONSTELLATION STAY HOME FOR PEACE banner frequently seen being towed over the city by recently retired navy flight instructor Lt. John Huyler, and the Constellation Vote stickers found everywhere on board the USS Constellation, including in the captain's personal bathroom.[17][18][19][20] Bathroom stickers weren't the only complication the captain had to deal with. Over 1,300 of the ship's sailors signed a petition requesting actress Jane Fonda's antiwar FTA Show, known to most GIs as the "Fuck The Army" show, be allowed on board. The captain refused this request but then got himself in hot water by intercepting and destroying 2,500 pieces of U.S. mail sent by antiwar activists to crewmembers. Faced with a possible court of inquiry and health problems, the captain was removed from command before the ship sailed.[21][11]

Research and pamphlet[edit]

Laying the basis for the broader SOS movement to come, a considerable amount of research was conducted into the role of aircraft carriers in modern warfare by Professor William Watson of MIT, who was then a visiting Professor of History at UC San Diego.[22] He argued in a widely distributed pamphlet that aircraft carriers had become weapons "used to crush popular uprisings and to bully the weaker and poorer countries of the world."[23]

The Connie 9[edit]

When the Constellation set sail for Vietnam in on October 1, 1971, nine of its crew publicly refused to go and took sanctuary in a local Catholic church, Christ the King. The "Connie 9", as they were quickly dubbed, were soon arrested in an early morning raid by U.S. Marshals and flown back to the ship, but within weeks were honorably discharged from the Navy.[24][25]

USS Coral Sea[edit]

As news of the efforts to stop the sailing of the Constellation spread, crewmen aboard the USS Coral Sea, an aircraft carrier stationed at Naval Air Station Alameda in the San Francisco area, decided to circulate a petition and the SOS movement officially acquired its name. Their “Stop Our Ship” petition stated in all capital letters: “THE SHIP CAN BE PREVENTED FROM TAKING AN ACTIVE PART IN THE CONFLICT IF WE THE MAJORITY VOICE OUR OPINION THAT WE DO NOT BELIEVE IN THE VIETNAM WAR.” It then asked fellow sailors to sign if they felt the ship should not go to Vietnam. The petition was started on September 12, 1971, and within three days it had gathered 300 signatures, at which point the ship's executive officer ordered it confiscated.[26][27][28]

Antiwar activity on board ship[edit]

Undeterred, the antiwar sailors created dozens of new copies and begin recirculating it with instructions about how to avoid confiscation. The military brass, however, declared the petition illegal and arrested three crewmen for passing out antiwar literature. With the ship now at sea for pre-deployment trials, a tit-for tat battle erupted. On September 28, 14 sailors passed out petitions and an antiwar GI underground newspaper in the mess hall in front of the captain. The captain responded by having several men arrested, some of whom claimed they were beaten in the brig. Word of these activities reached the civilian antiwar movement in the San Francisco area, and, when the Coral Sea passed under the Golden Gate Bridge as it returned to port on October 7, a large SOS banner was hung over the side of the bridge. Seventy crewmen responded in kind, forming the letters SOS on the flight deck as the ship passed under the bridge. The Navy then began to discharge those it viewed as leaders of the petition drive.[26]

Protests spread[edit]

By the time the dust had settled, over a 1,000 members of the crew had signed the petition – about 25% of the over 4,000 men assigned to the ship.[4] On November 6, over 300 men from Coral Sea marched with over 10,000 others in an anti-war demonstration in San Francisco.[29][30] In an unprecedented move the Berkeley City Council declared the city a sanctuary for the men on the Coral Sea who were refusing to go to war. The council encouraged city residents to "provide bedding, food, medical and legal help" to the sailors, and "passed a motion to establish a protected space where soldiers could access counseling and other support.”[31] Ten local churches also offered sanctuary.[32] In response a U.S. Attorney in San Francisco said “he would not hesitate to prosecute anyone who willfully harbors a military deserter”.[33] When the ship sailed on November 12, around 1,200 protestors demonstrated outside of Naval Air Station Alameda to encourage sailors not to sail and at least 35 crewmen failed to report for duty.[34][35][26][36]

On the way to Vietnam[edit]

When the Coral Sea arrived in Hawaii in late November, it was greeted by a special performance in Honolulu of the FTA antiwar show, featuring Jane Fonda, Donald Sutherland, and Country Joe McDonald.[37] More than 4,000 people attended, including approximately 2,500 members of the military and several hundred sailors from the Coral Sea.[38][39] After the show, approximately 50 crewmen met with the show's cast. When the ship pulled out of port to continue to Southeast Asia, another 53 sailors were missing.[3]: 112–113 In January 1972 with the ship off Vietnam, Secretary of the Navy John Chafee visited the Coral Sea. SOS activists on board held a demonstration and presented the Navy Secretary with a petition which 36 of them had signed.[40]

USS Kitty Hawk[edit]

Meanwhile, back in San Diego, another aircraft carrier, the USS Kitty Hawk, was preparing for deployment to Southeast Asia. Sailors on board, with help from the Concerned Military (the San Diego Concerned Officers Movement had broadened its membership to include enlisted personnel and changed its name) and civilian antiwar forces, began publishing their own newspaper called Kitty Litter and organizing a personalized version of SOS called “Stop the Hawk”. They circulated an antiwar petition which gathered several hundred signatures, but most copies were confiscated by superiors. On November 15, 1972, around 150 Kitty Hawk crewmen attended a rally to hear Joan Baez sing and listen to four of their crewmates speak out against the war.[41] Two days later, when the ship set sail for Indochina, 7 members of the crew publicly refused to sail and took refuge in local churches.[42][3]: 113

With the ship at sea, copies of Kitty Litter continued to be published by civilian supporters and mailed to antiwar crewmen who circulated them on board and submitted articles. One article published in the August 1972 issue pointed to a serious problem on board: "In two consecutive masts, Captain Townsend has put several black men into the brig for fighting with white men, while dismissing "with a warning" a white man who spoke in a demeaning manner to a black man and then proceeded to punch him in the stomach! Needless to say, this angered the black men on board, as well as many white men". Clearly more trouble was brewing on the Hawk that was soon starkly revealed (see below).[43][44]: 258

USS Enterprise[edit]

The world first nuclear-powered aircraft carrier, the USS Enterprise, was not immune from dissention. In mid-1972 a number of dissident sailors on board began publishing a mock version of the ship's official paper the Enterprise Ledger. Called the SOS Enterprise Ledger, it was virtually identical to the original except that it contained an antiwar and rebellious message. The ship's commanding officer responded by issuing regulations prohibiting the distribution of literature he hadn't approved. The SOS sailors decided they needed to learn more about military law and attended a class called “Turning the Regs Around” conducted by the Bay Area Military Law Panel. They then wrote and distributed a pamphlet outlining the legal rights of GIs.

They then knew they could legally petition Congress, so they created a petition opposing both the war in Vietnam and the military's denial of basic G.I. rights. The petition began circulating on board and was quickly gathering signatures when it was confiscated by the brass. The Navy was quite alarmed by this activity on board their ship, and naval intelligence agents were called in. They began interrogating known SOS activists about alleged sabotage incidents and threatening revocation of security clearances. Since most of the agents' questions were about SOS, SOS plans and past SOS activity, it seemed to the sailors that they were trying to find out more about SOS through scare tactics – as one sailor put it, “making us think we were going to be charged with sabotage to scare us into talking to clear ourselves."[45] When the ship set sail from Naval Air Station Alameda on September 12, 1972, 5 SOS organizers were escorted off the ship under armed guard, while antiwar GIs, vets and civilians protested on shore and members of the "Peoples Blockade" sailed small boats in the San Francisco Bay symbolically blocking the Enterprise.[3]: 115

Other aircraft carriers[edit]

When the USS Midway left Naval Air Station Alameda in April 1972, sixteen enlisted men assigned to Fighter Squadron 151 on board the carrier signed an antiwar letter to President Nixon.[3]: 114

On board the USS Ticonderoga in San Diego, sailors organized a movement they called “Stop It Now” (SIN), and 3 of the crew refused to board the ship when it set sail in May 1972. Once at sea, protests continued and there were reports of antiwar meetings of as many as 75 crew members.[3]: 114

In Norfolk, Virginia, on the East Coast, civilian antiwar groups organized against the sailing of the USS America. When it began to leave port on June 5, 1972, thirty-one activists in thirteen canoes and kayaks positioned themselves in front of the massive ship. “When the Coast Guard moved in to clear the demonstrators, hundreds of sailors on the deck of the America jeered and pelted the cutters with garbage; in a clear show of support for the protesters.”[3]: 114–115

Also in June, but at Alameda, civilians were protesting the pending departure of the USS Oriskany. “When the ship left, on June 6, as estimated twenty-five crew members refused to sail, including a group of ten men who turned themselves in to naval authorities on June 13 and issued a bitter public" statement.[3]: 115 In part they said: "the only way to end the genocide being perpetrated now in South East Asia is for us, the actual pawns in the political game, to quit playing."[46]

Civilian and veteran support groups for SOS[edit]

Given the strict discipline within the military as well as the not uncommon heavy handed response to internal dissent from military commanders, civilian support was an essential part of these military protests.[47]: 4, 74–75 [3]: 53–4 [48] From the beginning civilians and military veterans (many newly discharged from the very same ships) played a supporting role in the key Navy ports.

Center for Servicemen’s Rights[edit]

In San Diego, the local antiwar groups, including some of those who had waged the initial campaign against the USS Constellation, took their support to a more organized level by banding together in 1972 to form the Center for Servicemen’s Rights. They rented a large storefront space in the middle of the main GI strip which contained a bookstore, mimeo, meeting rooms and a stage; staffed by a "collective of volunteers that included active duty sailors, a few Marines, veterans, and civilian activists."[49] They provided individual and group counselling on GI rights, conscience objection and other means of opposing the war, as well as support for sailors who wanted to publish their own newspapers, leaflets or articles.[3]: 116

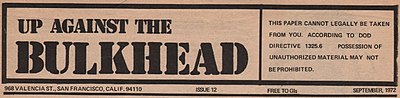

Up Against the Bulkhead[edit]

The San Francisco underground GI newspaper Up Against the Bulkhead and its staff played an important role in supporting the SOS movement, particularly the dissident sailors of the Coral Sea. Founded in 1970, by late 1971 it could be found everywhere GIs congregated in the San Francisco Bay Area and sailors knew where to go when they wanted counterculture help and friendship. As two Bulkhead staffers reported years later, "In 1971 a handful of sailors from the USS Coral Sea" showed up at the Bulkhead office "ready for action". The sailors "were a colorful lot, veritable hippies in uniform...more than eager not only to investigate ways to oppose the war, but also ways to sample the offerings of countercultural hedonism." With Bulkhead support the sailors went on to start the first SOS petition and officially launch the Stop Our Ship name.[28][50][51]

Subic Bay GI Center[edit]

In January 1972, attorneys from the National Lawyers Guild, worked with several active duty sailors to create a support center in Olongapo, Philippines, just outside U.S. Naval Base Subic Bay, the largest U.S. Navy installation in the Pacific at that time. Sparked by the appearance of the FTA Show in December, the center was soon publishing an underground newspaper called Seasick. The center supported dissenting GIs and worked to improve the conditions for sailors on shore leave, including by helping sailors gather over 500 signatures on a petition against police brutality by the shore patrol. The center was swiftly put out of business in September 1972 when martial law was declared in the Philippines (see below).[3]: 116 [52]

SOS offices[edit]

There were SOS offices in Oakland, serving the San Francisco Bay Area, and Los Angeles. In Los Angeles, the office opened in January 1972 with SOS standing for Support Our Soldiers, carrying on efforts initiated several years earlier by supporters of the GI Coffeehouse movement. They began putting out a newsletter called SOS News and announced in their first issue that they were “a support office for the GI Movement.” They pledged to take responsibility for “raising money, providing literature and films, recruiting staff, maintaining communications and providing publicity for GI coffeehouses and projects.”[53] In Oakland, the Support Our Soldiers office offered similar support to the GI movement. Their newsletter stated that they would "try to fill the needs for money, staff, educational materials, and communication that individual organizing projects cannot fulfill themselves."[54]

Increased air war leads to increased resistance[edit]

In March 1972 the last U.S. ground combat division was withdrawn from Vietnam just as the North Vietnamese Army launched the Nguyễn Huệ or Easter Offensive. The U.S. responded by massively increasing its air war. “One main component was to be a flotilla of Seventh Fleet aircraft carriers (twice as many as in 1971) massed in the Gulf of Tonkin”. As the air and naval activity in the Pacific intensified, drastic changes occurred within the Navy. “During the remainder of the year, as many as four carriers…were on combat station in the Tonkin Gulf at one time…. Normal fleet routine was completely disrupted…. For the crew members involved, the escalation created severe hardships”. And as the concerns of sailors for their safety at sea "became entangled with the enlarged Indochina war effort" it "led to protests against conditions that under other circumstances might have been bearable but, for the purpose of bombing Vietnam, were seen as intolerable”.[3]: 114, 117 Many of the sailors were already ambivalent or even antagonistic to the war, and now they were confronted with extremely intense and difficult, even unsafe, working conditions. The U.S.’s new strategy “was torpedoed by a massive antiwar movement among the sailors, who combined escalating protests and rebellions with a wide-spread campaign of sabotage.”[5]

[edit]

The Navy's sudden need for additional personnel greatly intensified the pressure for new recruits and training. The Naval Station Great Lakes, located north of Chicago, Illinois, is the largest U.S. Navy training base and the only boot camp for naval enlistees. On May 20, 1972, the Movement for a Democratic Military (MDM) and the Chicago Area Military Project organized an Armed Forces Day demonstration with 400 GIs joining a crowd of over 2,000. Soon a petition was being circulated on the base opposing the increased speed-up in training that gathered more than 600 signatures.

USS Nitro[edit]

Crew members aboard the USS Nitro, a munitions ship loaded with armament at the Naval Weapons Station Earle at Earle, New Jersey, staged one of the most dramatic protests. Worried about the war and the unsafe conditions on board they contacted civilian antiwar organizations who helped them draw up a list of specific shipboard hazards, which they circulated, gathering signatures from 48 members of the crew. The petition resulted in little change, but on April 24, 1972, as the ship was pulling out of port, it was greeted by an antiwar blockade of seventeen canoes and small boats. As the Coast Guard attempted to disperse the demonstrators, they were first confronted by dissent from within their ranks, and then, one of the Nitro's crew on the “ship’s deck suddenly stood up on the rail, raised the clenched-fist salute, and literally jumped overboard!” He was quickly followed by six more crew members, including one non-swimmer who had donned a life jacket.[3]: 118 [55]

William Monks, one of the seven who jumped explained his actions later:

I jumped from my ship because of my beliefs against the war and the killing in Vietnam. I also jumped to support the anti-war protesters who valiantly tried to keep the Nitro from leaving for Vietnam. I also jumped for the many oppressed people in the military that think like myself, but because of the way the military functions, no one ever listens to these people…. I see no reason why I should have to fight in Vietnam. I didn't start this war. I have nothing against the Vietnamese people, they never hurt me or my family.[55]

Racial conflicts and resistance[edit]

Colonel Robert D. Heinl, Jr. stated in a 1971 study in the Armed Forces Journal called “The Collapse of the Armed Forces”, that “Internally speaking, racial conflicts and drugs…are tearing the services apart today.”[2] Historians of the war have documented that non-white GIs were often given the dirtiest jobs and frequently sent to the front lines in combat situations.[56] A task force reporting to the Secretary of Defense at the time, Melvin R. Laird, found that racial discrimination in the military was not confined to the military but was “also a problem of a racist society”.[57] Historian Gerald Gill contended that by 1970 most black soldiers thought the war was a mistake, “hypocritical in intent and racist and imperialist by design.”[58] One black soldier was quoted as saying that black soldiers were sent on risky assignments by white officers so that ‘there would be one less nigger to worry about back home.’”[59]

In 1972 the problems that Heinl and others were describing in the Army were about to explode in the Navy. As an article in The New York Times put it, “The Navy, with its tradition of Filipino waiters and Southern WASP leadership, never really was an alternative for America's young city blacks during the early years of the Vietnam war.”[60] Navy commanders under pressure to increase recruitment to meet the needs of the expanding air war, “decided to change the Navy's image and its appeal to blacks.” By late 1972 approximately 12 percent “of new Navy recruits were black”, and they “were typically assigned to the ship's most miserable jobs”, and often "thrust into the dreariest, most menial, and most unpopular jobs on board"[61][44]: 259 Several unprecedented developments on board U.S. Navy ships dramatically exposed the intersection of antiwar sentiment, civil rights issues, discontent over working and safety conditions and racism. One of the first of these incidents highlighted many of the common threads between them.

Troublemakers in the Philippines[edit]

When martial law was declared in the Philippines in September 1972, the U.S. Navy “used the occasion to crack down on so-called troublemakers and…loaded more than two hundred enlisted men from eleven different ships onto planes for immediate transfer back to San Diego.”[3]: 119 [62][63] Once in San Diego many of the men wanted to let the public know what had happened and on October 24 “a racially mixed group of thirty-one enlisted men held a press conference to denounce the deplorable conditions, harassment, and racial prejudice they encountered while at sea.”[3]: 119 Their statement, partially excerpted here, captured many of the issues swirling within the Navy at that time:

We, the undersigned demand an end to the mistreatment and harassment that we have received from the United States Navy…. Living and working conditions on the ships were very poor. People had to work 14-16 hours a day. This Included watch and work. While we were on the line we got 4-6 hours sleep a night. At times we would work 24-36 hours straight without sleep…. There was a lot of pressure from our superiors. They keep trying to get us to do Jobs faster…. The superiors take out their frustrations on the enlisted people and especially on people of color.

The Captains and the command pushes the men and the machines to the breaking point. As a result the men turn to alcohol and drugs. It is an escape from the tension that is put on your mind and body by the long working hours and conditions. When the dope runs out or when the tension gets too great, fights break out on the ships. The tension results in racial fighting.

We demand an investigation into the working conditions, the living conditions, the tension on the Navy ships. We also demand an investigation to the drug program and the racism.[64]

The Kitty Hawk Riot[edit]

In October 1972 the Kitty Hawk pulled into Subic Bay after 8 months at sea, expecting a rest before heading home. Instead, the crew was notified they were returning to combat operations in Indochina. Tensions, already high from accelerated combat operations, flared even more. Blacks made up 7 percent of the enlisted crew on board the Hawk, and the majority of them “were assigned to the toughest and dirtiest Navy jobs, in the deck force and on flight decks, while whites populated the more coveted and higher tech jobs in the crew.”[61] The black crew members felt they had been “treated like dogs.”[65] With a strong sense of black pride and influenced by the civil rights and Black Power movements in the U.S., they were very unhappy with their conditions. During the nights prior to deployment, several racial incidents occurred in Subic Bay enlisted men's club. On October 8, a black sailor went on stage and shouted "Black power! This war is the white man's war!" and then continued to preach to the drunken crowd. A glass was thrown that hit him in the head, and a fight between blacks and whites broke out. On October 11, the night before the ship was to depart, a larger black-white fight erupted in the EM club which was broken up by a marine riot squad with clubs. Five black and four white sailors were arrested but returned to the ship before it departed. Back at sea, unhappy about being redeployed and overworked, many of the crew were now also deeply angry over racial tensions.[66]

Once underway on October 12, an investigating officer began an inquiry into the fight by summoning several black sailors. “This [singling out of blacks only] was hard to understand in terms of the tensions” The New York Times quoted an officer saying “who had access to all of the reports of the incident.” One of those summoned brought “nine companions with him and grew belligerent”. The nine then stormed out to join other black sailors on the mess deck with the crowd soon growing to over one hundred. The chief master-at-arms became alarmed and summoned the marines, a move which was described later by “officialdom” as the first of “a series of mistakes” and an explosive situation quickly developed.[60][3]: 120–121 [44]: 261–267

The ship's executive officer ordered the blacks and the marines to separate ends of the ship, but the captain issued conflicting orders. In the ensuing confusion, the blacks and the marines ran into each other on the hangar deck and a fight broke out. “The fighting spread rapidly, with bands of blacks and whites marauding throughout the ship’s decks and attacking each other with fists, chains, wrenches, and pipes.”[3]: 120–121 More conflicting orders were issued resulting in more confusion and fights raged on for much of the night. The fights left 40 white and 6 black sailors injured, including three who had to be evacuated to onshore medical facilities.[61][67]

By morning, a tense calm was achieved and normal flight operations were resumed.[44]: 266 However, once arrests were made for the fighting, all of the 25 arrested were black. “The arrest pattern caused as grave concern in some areas of the Pentagon as the outbreak itself. ‘Anytime you have a so-called race riot and you lock up 28 blacks,’ one black Navy official noted caustically during a recent interview, ‘that has to raise some questions.’”[60]

Mutiny on the Constellation[edit]

As word spread in the fleet about the incidents on board the Kitty Hawk, many of the black sailors on the Constellation were “swearing an affinity with their beleaguered brothers on the Kitty Hawk.”[44]: 268 By late October 1972, with the ship undergoing training exercises of the coast of Southern California, black crewmembers formed an organization called the “Black Fraction,” “with the aim of protecting minority interests in promotion policies and in the administration of military justice.” They elected a “chairman and three spokesmen to deal with the officers and petty officers of the ship.”[3]: 121–122 [68]

As commanders became aware of the Black Faction, they agreed to a meeting between them and the executive officer with the objective of easing tensions. Prior to the meeting, however, the command “singled out fifteen members of Black Faction as agitators and ordered that six of them be given immediate less-than-honorable discharges.” At the same time, notice was given ship wide that 250 men would be administratively discharged. Feeling they were being singled out for retaliation for their activism and fearing that most of the additional discharges would be directed at them, over one hundred sailors, including several whites, staged a sit in and refused to work on the morning of November 3.[3]: 121–122 [68]

During the day, members of the ship's Human Relations Council attempted to meet with the mutineers in a private dining room with little success as they demanded to see the captain. Around midnight, with the sit-in continuing the captain announced to the ship that any complaints had to go through the chain of command. “’O.K., that’s it,’ shouted a black sailor in the dining room. ‘They want another Kitty Hawk.’ There were shouts of ‘Let’s get the captain,’ and ‘Let’s take the ship.” The captain then called general quarters and ordered senior officers and petty officers to pick out white sailors and move to the mess deck to surround the mutineers where they had now moved. A tense standoff ensued that slowly dissipated overnight.[60][44]: 274 [69]

In the morning the captain “washe[d] his hands of the mutineers. He [did] not want to admit mutiny, so he cannot charge the blacks with that. Yet he want[ed] them off his ship.”[60] The captain, in consultation with others all the way up to the Chief of Naval Operations in Washington, decided to cut sea operations short and set the dissidents ashore. Once docked, 144 crew members left the ship, including 8 whites. The Constellation returned to sea but returned a few days later to pick up the mutinous sailors. Most of the men, however, refused to board the ship and on November 9 “staged a defiant dockside strike - perhaps the largest act of mass defiance in naval history.”[70] Despite these unprecedented actions, none of the sailors were arrested, most were simply reassigned to other duty stations, while a few received what were described as “trifling punishments”.[3]: 121–122 [44]: 280

Sabotage as resistance[edit]

As early as 1970 ships had been forced out of action by sabotage by crew members. For example, in June 1970 the destroyer USS Richard B. Anderson “was kept from sailing to Vietnam for eight weeks when crew members deliberately wrecked an engine.”[5]: 65 But, in tandem with the SOS Movement, naval sabotage became an even more serious issue in 1972 as the air war dramatically expanded.[71] “In July fires were started on the USS Forrestal and USS Ranger, the eighteenth instance of sabotage aboard the latter vessel, a prime target back home for peace activists’ ‘Stop Our Ships’ agitation.”[44]: 258 The fire on the Forrestal resulted in over $7 million in damage and was the largest single act of sabotage in naval history. In March 1972 when the aircraft carrier USS Midway received orders for Vietnam, “dissident crewmen deliberately spilled three thousand gallons of oil into the bay. The captain of the Constellation “told a press conference in November of 1972 that ‘saboteurs were at work’ during the period of unrest aboard his ship.” The Commander in Chief of the Atlantic Fleet stated in October 1972 that the increase in sabotage was a “grave liability” to the ability of the Navy to operate.[5][3]: 121–122

“All told, by the close of that year the United States Navy would log seventy-four instances of sabotage, more than half on aircraft carriers, none of them attributable to ‘enemy’ action.”[44]: 258 An investigation by the House Armed Services Committee revealed how much the sabotage had undermined naval combat operations and contributed to other forms of unrest during the 1972 bombing campaign. They stated that the October 1972 redeployment of the Kitty Hawk to combat which resulted in riots and near mutiny was apparently “due to the incidents of sabotage aboard her sister ships USS Ranger and USS Forrestal.”[3]: 123–126

Conclusion[edit]

While the SOS movement had no cohesive central organization or leadership, it was united by the overarching, if ultimately un-attained, goal of stopping warships from entering combat in Indochina. Despite this failure on the stated objective, it was a significant part of the latter stages of the overall anti-Vietnam War movement which did, in fact, help to end the war.[72]

See also[edit]

- A Matter of Conscience

- Brian Willson

- Concerned Officers Movement

- Court-martial of Howard Levy

- Donald W. Duncan

- FTA Show – 1971 anti-Vietnam War road show for GIs

- F.T.A. – documentary film about the FTA Show

- Fort Hood Three

- GI's Against Fascism

- GI Coffeehouses

- GI Underground Press

- Movement for a Democratic Military

- Opposition to United States involvement in the Vietnam War

- Presidio mutiny

- Sir! No Sir!, a documentary about the antiwar movement within the ranks of the United States Armed Forces

- The Spitting Image, a 1998 book by Vietnam veteran and sociology professor Jerry Lembcke which disproves the widely believed narrative that American soldiers were spat upon and insulted by antiwar protesters

- United States Servicemen's Fund

- Veterans For Peace

- Vietnam Veterans Against the War

- Waging Peace in Vietnam

- Winter Soldier Investigation

External links[edit]

- Sir! No Sir!, a film about GI resistance to the Vietnam War

- A Matter of Conscience - GI Resistance During the Vietnam War

- Waging Peace in Vietnam - US Soldiers and Veterans Who Opposed the War

References[edit]

- ^ a b c "The Encyclopedia of the Vietnam War, A Political, Social, and Military History, Second Edition 2011". ABC-CLIO. pp. 275, 1759.

- ^ a b Heinl, Robert D. (1971-06-07). "THE COLLAPSE OF THE ARMED FORCES". Armed Forces Journal.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Cortright, David (2005). Soldiers In Revolt. Chicago, IL: Haymarket Books. ISBN 1931859272.

- ^ a b Hutto, Jonathan (2008). Anti-War Soldier. New York, NY: Nation Books. pp. 63–64. ISBN 978-1-56858-378-5.

- ^ a b c d Franklin, H. Bruce (2000). Vietnam and other American fantasies. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press. pp. 65–67. ISBN 1-55849-279-8.

- ^ [1], Naval Base San Diego

- ^ "Archived Photograph of Francesco Da Vinci, founder of NVA".

- ^ Joan Baez Wearing Stay Home For Peace T-Shirt, Joan Baez Prior to Singing at a Constellation Vote Rally

- ^ [2], San Diego Nonviolent Action Anti-Aircraft Carrier Initial Statement; accessed December 23, 2017.

- ^ "Motorboat with 'Connie Stay Home' banner held by Francesco Da Vinci, the founder of Nonviolent Action. In the background is the USS Constellation". The Bob Fitch Photography Archive - Stanford University. Retrieved 2019-11-11.

- ^ a b "WAR FOES FIGHTING CARRIER'S RETURN; San Diego Poll Being Taken on Constellation's Future". The New York Times. 1971-09-19.

- ^ "Protest Vote Fails To Bar the Sailing Of Carrier to Asia". The New York Times. 1971-09-26.

- ^ "Liberty call (San Diego Concerned Officers Movement) :: GI Press Collection". content.wisconsinhistory.org.

- ^ [3] Constellation Vote Poster

- ^ The Connie Vote: The USS Constellation and the Peace Movement in San Diego, 1971, The Bob Fitch Photography Archive at Stanford University.

- ^ "Department of Defense Appropriations for Fiscal Year 1973, Hearings Before the 92nd Congress". books.google.com. U.S. Government Printing Office. December 1972. Retrieved 2021-02-11.

- ^ Fitch, Bob (1971). "Plane flying over San Diego with banner "CONNIE STAY HOME FOR PEACE"".

John Huyler flying with banner

- ^ Constellation Vote Logo, Constellation Vote Logo Used on Stickers and Flyers

- ^ Skelly, James (2017). The Sarcophagus of Identity: Tribalism, Nationalism, and the Transcendence of the Self. Stuttgart: ibidem Verlag. p. 135.

- ^ Praxis Underground Newspaper V.1 No.7, October 6, 1971 p.9, "Stay Home For Peace Stickers" Land GI in Brig

- ^ "Inquiry Asked in Navy Antiwar Material Case". The San Diego Union. 1971-06-07.

- ^ "MIT History". web.mit.edu.

- ^ [4], Attack Carrier: The Constellation Papers, September 1971

- ^ "9 Constellation Sailors Seized, Flown to Ship". The San Diego Union. 1971-10-03.

- ^ "'We've Won,' 8 Sailors Say on Discharge". The San Diego Union. 1971-12-08.

- ^ a b c [5], Stop Our Ship Leaflet p.2 (USS Coral Sea)

- ^ [6], Stop Our Ship Petition (USS Coral Sea)

- ^ a b Rees, Stephen; Wiley, Peter (2011). Carlsson, Chris; Elliott, Lisa Ruth (eds.). "Up Against the Bulkhead". Ten Years That Shook the City: San Francisco 1968-1978. San Francisco, CA: City Lights Publishers: 109–120. ISBN 978-1-931404-12-9.

- ^ "10,000 Protest in San Francisco". The Times Standard, Eureka, CA. 1971-11-07.

- ^ Hannon, Norm (1971-11-07). "S.F. Protest March Peaceful". Oakland Tribune.

- ^ "Berkeley Council Offers Sanctuary to War Critics". Eugene Register Guard. 1971-11-12.

- ^ Ridgley, Jennifer (2011). "Refuge, Refusal, and Acts of Holy Contagion: The City as a Sanctuary for Soldiers Resisting the Vietnam War". ACME: An International Journal for Critical Geographies. 10 (2): 189–214.

- ^ "US Attorney Will Prosecute Anyone Harboring Deserters". San Bernardino Sun. 1971-11-12.

- ^ "Coral Sea 'Anchor' Sought". The Times Standard, Eureka, CA. 1971-10-12.

- ^ "Sailors Sign Antiwar Petition". Star News, Pasadena, CA. 1971-10-12.

- ^ Elgert, Wally. "SOS - 1971". USS Coral Sea Sea Stories.

- ^ [7], Liberated Barracks Vol.1 No.3 Nov. 1971

- ^ "F.T.A. Show is Biting, Disrespectful, Well Done". Honolulu Star-Bulletin p.B8. 1971-11-26.

- ^ Ireland, B. (2011). The US Military in Hawai'i: Colonialism, Memory and Resistance. Palgrave Macmillan UK. p. 208. ISBN 978-0-230-22782-8.

- ^ [8], SOS From The Coral Sea - Supporting Materials for the film Sir! No Sir!

- ^ "Joan Baez Stars at Antiwar Rally". The San Diego Union p.B8. 1972-02-16.

- ^ "Kitty Hawk Sailing Today for Vietnam". The San Diego Union p.B5. 1972-02-17.

- ^ [9], Kitty Litter (USS Kitty Hawk Newsletter) 1972

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Guttridge, Leonard (1992). Mutiny: A History of Naval Insurrection. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0870212818.

- ^ [10], SOS Newsletter September 1972 p.3

- ^ [11], Camp News August 15, 1972 p.4

- ^ Parsons, David L. (2017). Dangerous Grounds: Antiwar Coffeehouses and Military Dissent in the Vietnam Era. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1-4696-3201-8.

- ^ Lane, Mark (1970-02-13). "Cops Attack Anti-war GIs". Los Angeles Free Press.

- ^ Cohn, Marjorie; Gilberd, Kathleen (2009). Rules of Disengagement. New York, NY: NYU Press. ISBN 9780981576923.

- ^ [12], Poster: A Warship Can Be Stopped - Support the Men of the Coral Sea

- ^ [13], Up Against the Bulkhead Underground Newspaper

- ^ [14], Seasick Underground Newspaper

- ^ [15], SOS News Los Angeles

- ^ [16], SOS News Oakland

- ^ a b [17], SOS News Los Angeles May 1972 p. 4

- ^ African Americans at War: An Encyclopedia, Volume 1. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. 2004. p. 502. ISBN 1576077462.

- ^ "Navy May Change Hats to Accommodate Blacks". Los Angeles Sentinel. 1972-12-07. p. A14.

- ^ Gill, Gerald (1990). Walter, Capps (ed.). "Black Soldiers Perspectives on the War". The Vietnam Reader. Routledge: 173–4, 181. ISBN 1136635629.

- ^ Graham, Herman (2003). The Brothers' Vietnam War: Black Power, Manhood, and the Military Experience. Gainesville, FL: University of Florida Press. pp. 21, 92. ISBN 0813026466.

- ^ a b c d e Hersh, Seymour (1972-11-12). "Some Very Unhappy Ships". The New York Times.

- ^ [18], Up From the Bottom" Underground Newspaper, Vol. 2 No. 6 p.8, Dec 15, 1972

- ^ "Defense Chief Unharmed - Philippines Sets Martial Law After Attack on Aide". The New York Times. 1972-09-23.

- ^ [19], SOS News Los Angeles Dec 1972 p. 4

- ^ Caldwell, Earl (1972-11-29). "Kitty Hawk Back at Home Port; Sailors Describe Racial Conflict". The New York Times.

- ^ Freeman, Gregory A. (2009). Troubled Water: Race, Mutiny, and Bravery on the USS Kitty Hawk. New York, NY: St. Martins Press. p. 83. ISBN 978-0230100541.

- ^ "Last Trial is Held in Kitty Hawk Case". The New York Times. 1973-04-11.

- ^ a b Leifermann, Henry (1973-02-18). "A sort of mutiny: The Constellation Incident". The New York Times.

- ^ Caldwell, Earl (1972-11-16). "Black Sailors and Ship's Captain Accuse Each Other". The New York Times.

- ^ Holles, Everett (1972-11-10). "130 Refuse to Join Ship; Most Reassigned by Navy". The New York Times.

- ^ Moser, Richard (1996). The New Winter Soldiers: GI and Veteran Dissent During the Vietnam Era. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. p. 88. ISBN 978-0-8135-2242-5.

- ^ Zinn, Howard (2017). A People's History of the United States. New York, NY: Harper Perennial. p. 469. ISBN 9780062397348.