| Stony Brook | |

|---|---|

Stony Brook in Jamaica Plain in 1898 | |

| Location | |

| City | Boston, Massachusetts, United States |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | Turtle Pond, Stony Brook Reservation |

| • coordinates | 42°15′56″N 71°08′30″W / 42.265499°N 71.1418°W |

| Mouth | Charles River Basin |

• coordinates | 42°21′07″N 71°05′32″W / 42.35187°N 71.092215°W |

| Length | 8.5 miles (13.7 km) |

| Discharge | |

| • average | 10 cu ft/s (0.28 m3/s) |

| • maximum | >1,000 cu ft/s (28 m3/s) |

Stony Brook is a 8.5-mile (13.7 km)-long subterranean river in Boston. The largest tributary stream of the lower Charles River, it runs mostly through conduits.[1] Stony Brook originates at Turtle Pond in the Stony Brook Reservation and flows through Hyde Park, Roslindale, Jamaica Plain, and Roxbury. It empties into the Charles River Basin just upstream of the Harvard Bridge. Stony Brook is fed by four tributaries, all of which are partially or entirely in conduits as well.

Stony Brook originally meandered across a flat valley and fed into the Back Bay; as the Back Bay was filled, it was directed into the Muddy River in the Back Bay Fens. It powered industries and its clear waters attracted breweries, but the surrounding lands tended to flood during heavy rains and freshets. A section in Roxbury was placed in a conduit in 1851; by 1867, all of Stony Brook north of Roxbury Crossing was in conduits. Additional channelization took place in Jamaica Plain and Roslindale in the 1870s and 1880s, and a conduit built in 1881–82 allowed heavy flows to be directed directly to the Charles River. An 1886 flood demonstrated a need for greater capacity in the downstream conduits.

A new conduit was built from Roxbury Crossing to the Fens in 1887–89, for use with Frederick Law Olmsted's plan to use the Fens as a holding basin for Stony Brook overflows. Due to upstream sanitation issues, storm flow was directed along a new conduit to the Charles in 1905. Conduits were extended south from the 1890s to the 1950s, leaving only the first 1 mile (1.6 km) of Stony Brook above ground. Sewer improvements in the 21st century reduced sewage flow into the Stony Brook during storms, in turn improving water quality in the Charles.

Route[edit]

Stony Brook originates at Turtle Pond in the Stony Brook Reservation. It flows about 1 mile (1.6 km) southeast through the park, then enters a conduit near the intersection of Enneking Parkway and Gordon Avenue.[2][1] The conduit zig-zags under residential areas, then follows the Northeast Corridor railroad line north for about 0.8 miles (1.3 km). It wanders north through residential areas of Hyde Park, Roslindale, and Jamaica Plain, largely paralleling the railroad line. Several streets are located on top of the conduit in this section, including American Legion Highway, Brookway Road, Stonley Road, and Meehan Street.[2] From Green Street to Tremont Street, the conduit is adjacent to the railroad alignment.[2]

North of Tremont Street, the conduit is located under Gurney Street, Parker Street, and Forsyth Way.[3][2] A pair of stone gatehouses (one disused) are located on the north side of the Fenway in the Back Bay Fens.[4] A conduit runs from the gatehouses north along the Fenway and Charlesgate East to a third gatehouse at Back Street. The Stony Brook discharges into the Charles River Basin north of the gatehouse, just upstream of the Harvard Bridge.[2][5] Normal dry-weather flow is about 10 cu ft/s (0.28 m3/s), though it can exceed 100 times that during storms.[1]

Stony Brook originally had four major tributaries, all of which are now partially or entirely buried in conduits.[2][1] The two branches of Goldsmith Brook run between Jamaica Pond and Arnold Arboretum, combining near the Arborway and meeting the main conduit near Boylston Street.[2] Bussey Brook runs parallel to the VFW Parkway and through the Arboretum, meeting the main conduit at Forest Hills; it runs on the surface except at its ends.[2][6] The Roslindale Branch runs from West Roxbury roughly parallel to the Needham Line, meeting the main conduit east of Roslindale Square.[2] Canterbury Brook runs west from near Codman Square, meeting Stony Brook near Neponset Avenue.[2] It is partially fed from Scarborough Pond in Franklin Park and has a surface segment along American Legion Highway.[6]

History[edit]

Early changes[edit]

Stony Brook originally fed into the Muddy River and the Back Bay in a windy channel.[3] It was known for its unusually clear water; a number of breweries including the Haffenreffer Brewery were located along its banks.[7] The flow also powered industry including mills and tanneries.[8][9] The Norfolk and Boston Turnpike was constructed along the Stony Brook valley in 1803, followed by the Boston and Providence Railroad in 1834.[7] (That section of the railroad is now the Southwest Corridor, which includes Stony Brook station.)[10]

The Stony Brook valley is very flat; during heavy rain and freshets, the brook would overflow its banks and inundate surrounding meadows. As development increased around the brook, this flooding became problematic (partially due to increased surface runoff from cleared land).[3] A section near Forest Hills station was placed in a culvert by 1845; this was extended in 1873.[8] In 1851, a segment in Roxbury east of Tremont Street was placed into a conduit. Culvert Street (now Whittier Street) was built over part of the conduit; other sections of the filled land were sold for development.[3] The segment from Tremont Street to the Back Bay basin was diverted into a conduit under Rogers Avenue and Bryant Street (now Forsyth Street) in 1865. The segment from Roxbury Crossing (Tremont Street at Pynchon Street) to Vernon Street was channelized and covered in 1866–67, completing improvements north of Roxbury Crossing.[3]

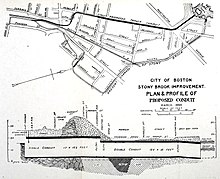

In 1873, the city of West Roxbury channelized Stony Brook through the Roslindale and Jamaica Plain neighborhoods.[3] After the 1873 annexation of Hyde Park, a similar channel was extended south from Roxbury Crossing to Jamaica Plain in 1880–84.[3] In 1881–82, a 7-by-7-foot (2.1 m × 2.1 m) conduit was constructed from Bryant Street under the east bank of the Muddy River to the Charles River. The Stony Brook Gatehouse controlled the flow of the Stony Brook; under normal conditions, the full flow was directed into the new conduit.[4] The four decades of channelizing and culverting the river were done haphazardly, with varying cross sections and slopes resulting in inconsistent attainable flow rates along the river.[3] Heavy rain and melting snow in February 1886 resulted in flows of 500 cu ft/s (14 m3/s), overwhelming the capacity of the culvert north of Roxbury Crossing. This resulted in flooding of 63 acres (25 ha) and 1,437 buildings, showing the inadequacy of the existing culverts.[3][4]

Sanitary channels[edit]

In 1887–89, a bypass conduit (the Commissioner's Channel) was constructed from Roxbury Crossing to Huntington Avenue, largely under Parker Street. It was built at a cost of $650,000 (equivalent to $20 million in 2023) and was among the largest storm sewers in the country.[3][11][4] From Huntington Avenue to the Muddy River, Stony Brook ran in a 42-foot (13 m)-wide open canal.[3] In the 1880s and 1890s, the Muddy River channel was reconstructed in the Fens under the direction of Frederick Law Olmsted to serve as a holding basin for storm overflow from the Muddy River and Stony Brook.[4] Connected to the tidal Charles River, it would be sanitized by seawater with the twice-daily tides.[12]

The railroad was raised onto an embankment through the Stony Brook Valley in the 1890s to eliminate grade crossings, and Columbus Avenue was widened around the same time.[8] The railroad project built a deeper conduit under Forest Hills, plus a new 2,600-foot (790 m) conduit between Boylston Street and Centre Street, while the Columbus Avenue project extended the conduit from Centre Street to Roxbury Crossing.[13][14] In 1896, the Boston Globe asserted that the "apparently inconsequential waterway has in its history cost more money to control and provide for than probably anything of its size in this part of the country".[15]

In 1897, the full flow of Stony Brook (rather than merely storm overflow) was redirected into the Commissioner's Channel and into the Fens.[12] Although a separate sewer had been built in the Stony Brook valley by the 1890s, it was inadequately sized to handle even small storms and was prone to breakage, resulting in sewage often entering the Stony Brook.[12][16] In 1898, the city was forced to dredge accumulated sewage from the Fens.[4][12] A new 12-by-12-foot (3.7 m × 3.7 m) conduit, paralleling the 1881-built conduit, was built in 1903–05 to carry the whole Stony Brook flow directly to the Charles River.[12][17][18][19] A second gatehouse was built to control flow into the new conduit.[12][4] The bridge carrying the Fenway over the no-longer-used canal was demolished with explosives in October 1905; the canal was filled in (partially with the bridge rubble) to create Forsyth Way.[12][20]

The construction of the Charles River Dam, which effectively changed the Charles River Basin from saltwater to freshwater, necessitated a conduit extension along the Charles River Esplanade in 1909. A third gatehouse was built at the connection point near Back Street and Charlesgate East.[12][21] By the time this work was complete, the city had spent over $5 million (equivalent to $121 million in 2023) controlling Stony Brook.[21] During the 1912–1914 construction of the Boylston Street subway, the Muddy River was temporarily redirected through the Stony Brook conduit.[22] Flow from the Stony Brook was later directed into the Charles River at the gatehouse (as had been the case from 1881 to 1909), as the Esplanade conduit (Boston Marginal Conduit) is a combined sewer that is routed to the Deer Island Waste Water Treatment Plant.[23][5] Work in the 20th and 21st centuries gradually reduced industrial pollution and sewage flows into Stony Brook. A $45 million project, lasting from 2000 to 2006, installed 14 miles (23 km) of new storm drains and reduced sewage flows into Stony Brook during storms by 99.7%. This in turn has contributed to improved water quality in the Charles River.[24][25]

Southern section[edit]

Stony Brook Reservation, which includes Turtle Pond and the first 1 mile (1.6 km) of Stony Brook, was established as a park in 1894.[26] The remaining part of the river from Hyde Park to Jamaica Plain was gradually placed in conduits. Work began to extend the conduit south from Boylston Street in 1897, and reached Green Street in 1901.[27][28] The conduit was extended south through Forest Hills Yard to Forest Hills Square in 1910–11.[29][30] Work around 1921 added a section of conduit south of Forest Hills, plus a conduit for the Roslindale Branch as far as Roslindale Square.[31][32][33]

The remaining surface sections in Roslindale and Hyde Park (outside the Stony Brook Reservation) were placed in conduits in the 1930s to 1950s.[7][34][35][36] The conduit under the Arborway was replaced in the early 1950s for construction of the Casey Overpass.[8] In 1951, Brookway Road was constructed over the culvert south of Forest Hills.[37] Three years later, a former Stony Brook culvert under the railroad (disused decades before when the river was placed underground) at the end of the street was reused as a pedestrian underpass.[38] When the new underground Forest Hills station was constructed in the 1980s, the conduit there was relocated even deeper.[8]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d Weiskel, Peter K.; Barlow, Lora K.; Smieszek, Tomas W. "Water Resources and the Urban Environment, Lower Charles River Watershed, Massachusetts, 1630–2005". CIR 1280, Water Resources and the Urban Environment, Lower Charles River Watershed, Massachusetts, 1630–2005. US Geological Survey, US Department of the Interior.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Boston Water and Sewer Commission - IDDE Priority Ranking - January 2017". 2016 Stormwater Management Report (PDF). Boston Water and Sewer Commission. 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Carter, Henry H. (October 1892). "Stony Brook Improvement". Journal of the Association of Engineering Societies. 11 (2). Association of Engineering Societies: 500–513 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Report of the Boston Landmarks Commission on the potential designation of BACK BAY FENS as a Landmark under Chapter 772 of the Acts of 1975, as amended" (PDF). Boston Landmarks Commission. 1983.

- ^ a b "Evaluation of Stormwater Management Benefits to the Lower Charles River" (PDF). New England Interstate Water Pollution Control Commission and U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. August 2004. p. 1.

- ^ a b "Section 4: Environmental Inventory & Analysis". Open Space & Recreation Plan 2015–2021 (PDF). City of Boston. January 2015. pp. 42–43.

- ^ a b c "Stony Brook". Heart of the City Project. Center for Urban and Regional Policy, Northeastern University. 2002. Archived from the original on September 7, 2006.

- ^ a b c d e Heath, Richard (January 25, 2013). "A HISTORY OF FOREST HILLS" (PDF). Jamaica Plain Historical Society.

- ^ "Boston's Costly Little Stream". Boston Globe. July 12, 1908. p. 47 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Belcher, Jonathan. "Changes to Transit Service in the MBTA district" (PDF). Boston Street Railway Association.

- ^ Johnston, Louis; Williamson, Samuel H. (2023). "What Was the U.S. GDP Then?". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved November 30, 2023. United States Gross Domestic Product deflator figures follow the MeasuringWorth series.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Seasholes, Nancy S. (2018). Gaining Ground: A History of Landmaking in Boston. MIT Press. pp. 215–229. ISBN 9780262350211 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Job Will Cost Three Million". Boston Globe. September 25, 1894. p. 5 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "10,500 Miles of Streets". Boston Globe. May 18, 1895. pp. 1, 3 – via Newspapers.com. (second page)

- ^ "On Elevated Tracks Sunday". Boston Globe. August 20, 1896. p. 7 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Examination of Sewer Outlets – Pollution of Stony Brook". Thirty-Eighth Annual Report of the State Board of Heath of Massachusetts. Wright and Potter. 1907. pp. 50–53 – via Google Books.

- ^ "To Abate Sewage Nuisance". Boston Globe. June 6, 1903. p. 12 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Work of Purifying the Back Bay Fens begun". Boston Globe. October 19, 1903. p. 3 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Charles River Basin – III". City Affairs. Vol. 1, no. 4. June 1905 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Bridge Blown Up". Boston Globe. October 4, 1905. p. 6 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "A Five-Million-Dollar Brook". Boston Globe. August 22, 1909. p. 57 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Boston Transit Commission (1912). Annual report of the Boston Transit Commission, for the year ending June 30, 1912. pp. 39–40 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Wu D, Daquioag J. "Appendix I: An Overview of the MWRA Sewerage System and Facilities" (PDF). Technical Report No. 2001-04: NPDES compliance summary report, fiscal year 2000. Massachusetts Water Resources Authority. p. I-5.

- ^ "CSO PROJECTS HAVE MADE DRAMATIC IMPROVEMENTS TO WATER QUALITY" (Press release). Massachusetts Water Resources Authority. April 17, 2007.

- ^ Boston Parks and Recreation Department (January 21, 2009). "Attachment A: Project Narrative" (PDF). Notice of Intent: Muddy River Flood Damage Reduction and Environmental Restoration Project Phase 1. p. 6.

- ^ Report of the Board of Metropolitan Park Commissioners (Report). Massachusetts Metropolitan Park Commission. 1917. p. 9 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Stony Brook Being Imprisoned". Boston Globe. October 23, 1901. p. 5 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Hard to Fight". Boston Globe. August 14, 1902. p. 12 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "West Roxbury District". Boston Globe. August 30, 1910. p. 8 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "West Roxbury District". Boston Globe. November 14, 1910. p. 4 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Appendix D: Report of the Division Engineer of the Sewer and Sanitary Division". Annual Report for the Public Works Department for the Year 1920. City of Boston. 1921. p. 451 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "Appendix D: Report of the Division Engineer of the Sewer and Sanitary Division". Annual Report for the Public Works Department for the Year 1921. City of Boston. 1922. p. 4578 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "Appendix D: Report of the Division Engineer of the Sewer and Sanitary Division". Annual Report for the Public Works Department for the Year 1922. City of Boston. 1923. p. 130 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "Health and Sanitary Conditions Improved in Stony Brook Area". Boston Globe. August 8, 1936. p. 5 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Street Board Awards $452,000 in Contracts". Boston Globe. September 24, 1946. p. 7 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Hynes Asks Council Okay on $4,000,000 Road Work". Boston Globe. February 15, 1955. p. 3 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Hearings". Boston Globe. August 17, 1955. p. 15 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Pedestrian Tunnel Under R.R. Tracks Set for Hyde Park". Boston Globe. November 19, 1954. p. 7 – via Newspapers.com.

External links[edit]

![]() Media related to Stony Brook (Boston, Massachusetts) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Stony Brook (Boston, Massachusetts) at Wikimedia Commons