Nellah Massey Bailey | |

|---|---|

| |

| Mississippi State Tax Collector | |

| In office January 19, 1948 – March 31, 1956 | |

| Governor | Fielding L. Wright Hugh L. White James P. Coleman |

| Preceded by | Carl Craig |

| Succeeded by | William Winter |

| First Lady of Mississippi | |

| In role January 18, 1944 – November 2, 1946 | |

| Governor | Thomas L. Bailey |

| Preceded by | Clara Murphree |

| Succeeded by | Nan Wright |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Nellah Izora Massey June 30, 1893 Birmingham, Alabama, U.S. |

| Died | March 31, 1956 (aged 62) Meridian, Mississippi, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 2 |

Nellah Izora Massey Bailey (née Massey; June 30, 1893 – March 31, 1956) was an American politician and librarian. She was the first lady of Mississippi from 1944 to 1946 and the Mississippi state tax collector from 1948 to 1956. A member of the Democratic Party, she was the first woman elected to statewide office in Mississippi.

Born in Birmingham, Alabama, Bailey attended library school in Chautauqua, New York, and worked at the public library in Meridian, Mississippi, for thirty years. She married future governor Thomas L. Bailey in 1917. As the first lady of Mississippi, she chaired the Mississippi Joint Recruitment Campaign, a statewide canvass that encouraged women to serve in the United States Armed Forces during World War II.

In 1947, Bailey entered the race for Mississippi state tax collector. She won the Democratic primary and ran unopposed in the general election. She was re-elected in 1951 and 1955, but died three months into her third term after a series of heart attacks.

Early life and education[edit]

Nellah Izora Massey was born on June 30, 1893, in Birmingham, Alabama.[5] She was the daughter of Charles Carter Massey, a firefighter with the Birmingham fire department, and Jessie Irene Massey (née Pope).[4][6] In 1913, she moved to Meridian, Mississippi, when her father became assistant chief of the Meridian fire department.[7] After graduating from Meridian High School, Massey attended library school in Chautauqua, New York before completing an apprenticeship in library work in Birmingham.[8]

Library career, marriage, and family[edit]

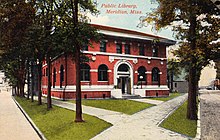

In 1913, Massey returned to Meridian to start a new position as an assistant librarian at a newly established Carnegie library.[8][9] The library was one of the two segregated libraries in Meridian that were opened that year with funding from philanthropist Andrew Carnegie.[10] She was promoted to head librarian in 1934 and remained in the position until 1943, shortly before her move to Jackson.[8] She was elected vice president of the Mississippi Library Association in 1936,[11] and was appointed as an assistant liaison librarian to the 4th Corps Area in 1942 by Charles Harvey Brown, the president of the American Library Association.[12]

During this time, Massey was also active in women's service organizations. In 1932, she was elected president of the Meridian Pilot Club, which was a local chapter of Pilot International, an organization similar to Rotary International.[11][13] She was the president of Pilot International from 1936 to 1937.[11][14] She was also a charter member of the Business and Professional Women's Clubs in Mississippi, and a member of Delta Kappa Gamma and the Pushtahama chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution.[15] For eight years, she chaired the Lauderdale County chapter of the March of Dimes.[16]

It was during her time as assistant librarian at the Meridian public library that Massey met Thomas Lowry Bailey, an attorney who was on the judging committee for a local word contest. Massey kept the library open after hours each evening so the committee members could consult the encyclopedias and dictionaries. Thomas Bailey began staying later each evening, after the other committee members had left, to help Massey with the building closing procedures; they eventually started dating, and were married on August 22, 1917.[1][15]

They had a son, Harold Melby Bailey (born 1922 or 1923), who was adopted at two months old, and a daughter, Nellah Pope Bailey (born 1925 or 1926).[1][13][15] In 1935, the family's car overturned twice on Mississippi Highway 15; Bailey suffered two fractured ribs and body bruises.[17]

First Lady of Mississippi (1944–1946)[edit]

The Baileys moved to the Mississippi Governor's Mansion in Jackson on January 9, 1944,[18] and Nellah Massey Bailey became the first lady of Mississippi when Thomas Bailey took office as governor on January 18, 1944.[19] She remained in the role until Governor Bailey died on November 2, 1946, from surgical complications during a procedure to remove a spinal tumor.[20]

World War II women recruitment initiative[edit]

In March 1944, during World War II, Bailey became the state chair of the newly established Mississippi Joint Recruitment Campaign.[21] Sponsored by the Mississippi Office of Civilian Defense, the campaign sought to conduct a statewide house-to-house survey of women who were eligible to serve in the four women's branches of the United States Armed Forces: the Women's Army Corps, the Navy Women's Reserve, the Coast Guard Women's Reserve, and the Marine Corps Women's Reserve.[22] The program's mission was not to conscript eligible women, but rather to provide enlistment information to those interested in joining a branch of service.[23]

Bailey believed that women had a duty to fight in the war, saying: "We leaders of our state must break down the prejudice which exists in Mississippi against women in the service. It is an honor for a young woman to serve her nation in this day of strife." She pushed back against claims that women would become "less feminine" after serving in the Armed Forces, and said that they would gain "poise and character" through their service.[24]

As state chair, Bailey appointed an executive committee, consisting of statewide leaders of civic, fraternal, and service organizations as well as representatives of the women's branches of the Armed Forces, and mayors across the state were directed to form local committees to conduct the canvasses in each community.[25] Initially planned to be a three-week campaign, it received enthusiastic support across the state, and the national women's branches of the Armed Forces extended the time that their representatives would visit communities for further recruitment.[26] Althea O'Hanlon, a field liaison representative for the national Office of Civilian Defense, remarked that "Mississippi has blazed the trail for a new era in the recruitment of women for the various services."[27] The campaign was the first of its kind to be established in any state;[28] Georgia later developed a similar program based on Mississippi's example.[29]

Mississippi state tax collector (1948–1956)[edit]

1947 campaign[edit]

According to the Clarion-Ledger, many people had expected Bailey to run for statewide office.[30] In January 1947, when the U.S. Senate initially refused to re-seat Mississippi senator Theodore G. Bilbo due to admissions of racist voter suppression and bribery, the Jackson Business and Professional Women's club endorsed Bailey for the potential senatorial interim seat, though Bailey declined to comment on a potential appointment.[31] No appointment was ultimately made when senators reached an agreement that Bilbo would remain under consideration while he underwent treatment for oral cancer.[32]

Incumbent Mississippi state tax collector Carl Craig announced his intention to run for state auditor on February 15, 1947.[33] Bailey qualified for the open race for state tax collector on May 17, 1947; she was the first woman to run for statewide office in Mississippi.[30] She used her late husband's name in her political activities, campaigning as "Mrs. Thomas L. Bailey".[34] At her candidate qualification, Bailey said: "The next four years will see the accomplishment of many of the dreams and programs of Governor Bailey, and it is but natural that I want to be a part of that administration. Tom Bailey worked hard for Mississippi, and I shall endeavor to give my best to the state he loved so well."[30]

Two other candidates had announced their intention to run for state tax collector: O. D. Loper, who worked in the state auditor's office, and Potts Johnson, a farmer from Jackson.[35][36] Upon learning that Bailey entered the race, Johnson withdrew his candidacy and endorsed her, saying:

We men in Mississippi have been asking women to vote for us for state offices ever since woman suffrage was adopted. Any man who would claim that a woman should not hold at least one out of the ten elective state offices is insulting the intelligence of every woman voter in Mississippi. A woman can supervise this tax collecting work as good as a man, and Mrs. Bailey's capacity as an executive is well known in Mississippi.[37]

Bailey defeated Loper in the Democratic primary with 60.5 percent of the vote,[38] and was unopposed in the general election.[39] She was sworn in as state tax collector on January 19, 1948, becoming the first woman to hold statewide elected office in Mississippi.[40][41]

Tenure and re-election campaigns[edit]

Mississippi's tax on liquor figured prominently during Bailey's tenure as state tax collector. At the time, Mississippi and Oklahoma were the only two remaining dry states that had not repealed prohibition legislation.[42] However, difficulty in enforcing the law, particularly in "wet areas" of the state, resulted in a ten percent "black market" tax on all sales of liquor, despite its illegal status.[43] During Bailey's term, black market tax revenues reached record highs.[42] The state tax collector's office took a ten percent commission of all taxes, making the position the most lucrative elected office in the state (by comparison, the governor's annual salary was $15,000).[44]: 104

C. W. Pitts, a former state highway patrolman, announced his candidacy for state tax collector in April 1951, challenging Bailey in the Democratic primary. He ran on a platform that advocated for the repeal of the black market tax.[45][46] Robert W. May, the incumbent term-limited Mississippi state treasurer, also entered the race that month. During a candidate forum, May criticized Bailey and accused her of overreliance on unelected deputies, while Pitts pledged to give half of his collection profits to charity and said that the position of state tax collector should be "a man's job". Bailey responded by arguing that the profits were divided among the 17 office employees.[47]

Bailey defeated Pitts and May in the Democratic primary election, garnering 54.4 percent of the vote and avoiding a runoff election.[48] She was unopposed in the general election and was sworn into her second term on January 21, 1952.[49][50]

The 1955 Democratic primary for state tax collector had four candidates, including Howard H. Little, a member of the Mississippi Public Service Commission.[51] Bailey received 44.8 percent of the vote in the election; because no candidate received a majority of the vote, the primary went to a runoff between Bailey and Little, who received 30.0 percent of the vote.[52] Despite the other two eliminated candidates endorsing Little,[53] Bailey defeated Little in the runoff election by a five-point margin.[54]

Death and legacy[edit]

Three months into her third term as state tax collector, Bailey had a series of heart attacks. She died at age 62 on March 31, 1956, at Riley Memorial Hospital (now Anderson Regional Medical Center) in Meridian. The funeral took place at the Central Methodist Church in Meridian on April 2, 1956, and she was interred in Magnolia Cemetery.[55] After her death, one of Bailey's close friends, state representative Betty Jane Long, introduced a resolution of respect that was adopted by the Mississippi House of Representatives.[55] The Clarion-Ledger wrote: "Many Mississippi women were proud of her achievements and many may eventually be inspired by her record to seek election to office."[56] There was much speculation among state lawmakers about whom Governor James P. Coleman would appoint to the lucrative position to replace Bailey; Coleman ultimately named state representative William Winter to serve the remainder of Bailey's term.[44]: 104 Winter was the last person to hold the office of state tax collector before it was abolished at his recommendation in 1964.[44]: 118

A portrait of Bailey, donated by her grandson Thomas Webb, has been displayed at the Old Capitol Museum in Jackson since 2019.[57]

Electoral history[edit]

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Mrs. Thomas L. Bailey | 215,962 | 60.5 | |

| Democratic | O. D. Loper | 141,258 | 39.5 | |

| Total votes | 357,220 | 100.0 | ||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Mrs. Thomas L. Bailey (incumbent) | 212,371 | 54.4 | |

| Democratic | Robert W. May | 136,554 | 35.0 | |

| Democratic | C. W. Pitts | 41,393 | 10.6 | |

| Total votes | 390,318 | 100.0 | ||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Mrs. Thomas L. Bailey (incumbent) | 187,473 | 44.8 | |

| Democratic | Howard H. Little | 125,447 | 30.0 | |

| Democratic | Roy Pitts | 65,225 | 15.6 | |

| Democratic | N. R. Thomas | 40,064 | 9.6 | |

| Total votes | 418,209 | 100.0 | ||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Mrs. Thomas L. Bailey (incumbent) | 190,440 | 52.7 | |

| Democratic | Howard H. Little | 171,228 | 47.3 | |

| Total votes | 361,668 | 100.0 | ||

References[edit]

- ^ a b c Duren, W. L., ed. (September 7, 1939). "Conference News & Personals". New Orleans Christian Advocate. Louisiana, Mississippi, and North Mississippi Conferences, Methodist Episcopal Church, South. p. 7. Retrieved January 17, 2021.

- ^ Hewitt, Purser (June 30, 1955). "Hewitt to the Line". Clarion-Ledger. p. 16. Retrieved January 21, 2021.

- ^ Sansing, David G. (2017). "Bailey, Thomas Lowry". In Ownby, Ted; Wilson, Charles Reagan; Abadie, Ann J; Lindsey, Odie; Thomas Jr, James G (eds.). The Mississippi Encyclopedia. University Press of Mississippi. p. 63. ISBN 978-1-4968-1159-2.

- ^ a b Bookhart, Mary Alice (October 6, 1954). "The Distaffer". Clarion-Ledger. p. 4. Retrieved January 16, 2021.

- ^

- ^ "Fire Chief Massey Dies Quite Suddenly". Nashville Banner. Associated Press. January 1, 1909. p. 12. Retrieved January 17, 2021.

- ^ "C. C. Massey Assistant Chief". The Birmingham News. June 6, 1903. p. 19. Retrieved January 20, 2021.

- ^ a b c "Mrs. Bailey's Hobby Is Quilting; 'Thomas L.' Easy to Feed, She Says". Hattiesburg American. January 19, 1944. p. 7. Retrieved January 17, 2021.

- ^ "Mrs. Bailey Speaker For Birthday Party Of Pilot Club". Selma Times-Journal. February 15, 1948. p. 12. Retrieved January 19, 2021.

- ^ Owens, Cheryl (March 4, 2017). "Study stirs memories of segregated library in Meridian". The Meridian Star. Retrieved January 19, 2021.

- ^ a b c "Pilot Club Head Arranging Visit". El Paso Times. May 26, 1937. p. 6. Retrieved March 8, 2021.

- ^ "Liaison and Assistant Liaison Librarians". American Library Association Bulletin. 36 (5): 363. 1942. JSTOR 25691006.

- ^ a b "Prophecy of Class Will Be Fulfilled in Election Of Bailey as Governor". Enterprise-Journal. July 20, 1939. p. 6. Retrieved March 8, 2021.

- ^ "Through The Years: Presidents of Pilot International". Pilot International. January 24, 2014. Retrieved March 8, 2021.

{{cite magazine}}: Cite magazine requires|magazine=(help) - ^ a b c "Baileys to Share Honors Today as Chief is Crowned". Clarion-Ledger. January 18, 1944. p. 17. Retrieved January 20, 2021.

- ^ "First Lady Opens Drive". Greenwood Commonwealth. January 27, 1944. p. 7. Retrieved March 8, 2021.

- ^ "Baileys hurt in car wreck". The Winston County Journal. May 31, 1935. p. 1. Retrieved March 8, 2021.

- ^ "Baileys move in". Hattiesburg American. January 10, 1944. p. 9. Retrieved March 8, 2021.

- ^ "Louisiana Chief's Wife At Reception". Clarion-Ledger. January 20, 1944. p. 10. Retrieved January 18, 2021.

- ^ "Gov. T.L. Bailey, 58, Dies in Mississippi; Chief Executive Since 1944-- While in State Legislature Opposed Bilbo Measures". The New York Times. November 3, 1946. Retrieved March 8, 2021.

- ^ "Mrs. Thomas Bailey To Head State Recruiting Of Women". Delta Democrat Times. March 27, 1944. p. 3. Retrieved January 18, 2021.

- ^ "Womanpower Survey To Be Made". The Greenwood Commonwealth. April 10, 1944. p. 1. Retrieved January 18, 2021.

- ^ "Cooperation Asked In Recruit Survey". Clarion-Ledger. May 7, 1944. p. 4. Retrieved January 18, 2021.

- ^ "Series of Statewide Meetings to Set Up State Women's Joint Recruitment campaign". Clarion-Ledger. April 6, 1944. p. 2. Retrieved January 18, 2021.

- ^ "Mrs. Bailey Appoints Executive Committee For Joint Recruitment". Clarion-Ledger. April 13, 1944. p. 5. Retrieved January 18, 2021.

- ^ "30 Cities In State Conduct Girl Survey". Clarion-Ledger. April 27, 1944. p. 7. Retrieved January 18, 2021.

- ^ "State Creates Stir With Recruiting Plan". Delta Democrat Times. April 23, 1944. p. 6. Retrieved January 18, 2021.

- ^ "Gov. Bailey Launches Recruiting Drive". The Greenwood Commonwealth. April 11, 1944. p. 3. Retrieved January 18, 2021.

- ^ "Georgia to Follow Mississippi's Plan". Clarion-Ledger. May 18, 1944. p. 5. Retrieved January 18, 2021.

- ^ a b c "Mrs. Thomas Bailey Enters State Race". Clarion-Ledger. May 18, 1947. p. 2. Retrieved January 16, 2021.

- ^ "Governor May Name Bilbo as Interim Senator". The Decatur Daily Review. Associated Press. January 9, 1947. p. 1. Retrieved January 19, 2021.

- ^ "The Election Case of Theodore G. Bilbo of Mississippi (1947)". United States Senate. United States Senate. Retrieved January 19, 2021.

- ^ "Know Your Government Better". Clarion-Ledger. February 16, 1947. p. 12. Retrieved January 17, 2021.

- ^ Pettus, Emily Wagster (January 3, 2020). "Analysis: 6 women have held statewide office in Mississippi". Associated Press. Retrieved January 17, 2021.

- ^ "Mrs. Bailey To Seek Tax Collector Post". Leland Progress. May 22, 1947. p. 1. Retrieved January 19, 2021.

- ^ "Potts Johnson Seeks Tax Collector's Job". Clarion-Ledger. May 18, 1947. p. 2. Retrieved January 17, 2021.

- ^ Graves, John Temple (May 28, 1947). "This Morning". The LaFayette Sun. p. 1. Retrieved January 17, 2021.

- ^ a b "Hamilton Refuses to Withdraw". Hattiesburg American. August 12, 1947. p. 1. Retrieved January 17, 2021.

- ^ Baker, Frances (August 19, 1947). "New Era For Women In Public Life Predicted". Enterprise-Journal. p. 2. Retrieved January 19, 2021.

- ^ "Eight State Officers Elected in Primary". Simpson County News. August 7, 1947. p. 6. Retrieved March 24, 2021.

- ^ Hills, Charles M (January 20, 1948). "Lieutenant Governor, Thirteen Department Heads Take Oaths". Clarion-Ledger. p. 1. Retrieved January 17, 2021.

- ^ a b "Dry States Cash In On Illegal Liquor Trade". The Courier-Journal. August 13, 1950. p. 46. Retrieved January 20, 2021.

- ^ Toler, Kenneth (June 6, 1948). "The Deep South: 'Dry' Mississippi Collects Tax On Illegal Liquor Sales". The New York Times. Retrieved January 20, 2021.

- ^ a b c Bolton, Charles C (2013). William F. Winter and the New Mississippi: A Biography. University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 978-1-6170-3787-0.

- ^ "Pitts for Collector". Enterprise-Journal. April 3, 1951. p. 1. Retrieved January 20, 2021.

- ^ "May To Make Race for Tax Collector". Clarion-Ledger. April 15, 1951. p. 9. Retrieved January 20, 2021.

- ^ "Executive Candidates Address 5,000 At Carthage Saturday". Clarion-Ledger. May 27, 1951. p. 11. Retrieved January 20, 2021.

- ^ a b "Record Vote Is Certified". Hattiesburg American. August 14, 1951. p. 1. Retrieved January 19, 2021.

- ^ "State Jobs to be Filled After Runoff". Enterprise-Journal. August 10, 1951. p. 1. Retrieved January 20, 2021.

- ^ "Gartin Takes Oath Today". Clarion-Ledger. January 21, 1952. p. 1. Retrieved January 20, 2021.

- ^ "Howard Little To Run For Collector". Clarion-Ledger. January 5, 1955. p. 3. Retrieved January 21, 2021.

- ^ a b "Official Returns of the State". The Winston County Journal. August 12, 1955. p. 9. Retrieved January 19, 2021.

- ^ "Little Has Support Of Two Ex-Candidates". Enterprise-Journal. August 11, 1955. p. 1. Retrieved January 19, 2021.

- ^ a b "Officials For Next Four-Year Term". The Newton Record. August 25, 1955. p. 1. Retrieved January 19, 2021.

- ^ a b "Mrs. T. L. Bailey Dies Saturday in Meridian". The Columbian-Progress. April 5, 1956. p. 8. Retrieved January 16, 2021.

- ^ "Mrs. Nellah Massey Bailey". Clarion-Ledger. April 3, 1956. p. 6. Retrieved March 8, 2021.

- ^ Barnette, Candace (February 22, 2019). "Prominent Meridianites on display at the Capitol". WTOK. Retrieved January 18, 2021.