| Fracking |

|---|

|

| By country |

| Environmental impact |

| Regulation |

| Technology |

| Politics |

Fracking in the United States began in 1949.[1] According to the Department of Energy (DOE), by 2013 at least two million oil and gas wells in the US had been hydraulically fractured, and that of new wells being drilled, up to 95% are hydraulically fractured. The output from these wells makes up 43% of the oil production and 67% of the natural gas production in the United States.[2] Environmental safety and health concerns about hydraulic fracturing emerged in the 1980s, and are still being debated at the state and federal levels.[3][4][5]

New York banned massive hydraulic fracturing by executive order in 2010, so all natural gas production in the state is from wells drilled prior to the ban.[6] Vermont, which has no known frackable gas reserves, banned fracking preventatively in May 2012. In March 2017, Maryland became the second state in the US with proven gas reserves to pass a law banning fracking.[7] On May 8, 2019, Washington became the fourth state to ban fracking when Governor Jay Inslee signed SB 5145 into law after it passed the State Senate by a vote of 29-18 and the House 61–37. Washington is a non-oil and gas state that had no fracking operations when the bill was passed.[8][9]

An imbalance in the supply-demand dynamics for the oil and gas produced by hydraulic fracturing in the Permian Basin of west Texas is an increasing challenge for the local industry, as well as a growing impact to the environment. In 2018, so much excess natural gas was produced with oil that prices turned negative and wasteful flaring increased to a record 400 million cubic feet per day.[10] By Q3 of 2019, the wasted gas from this region alone almost doubled to 750 million cubic feet per day,[11] an amount more than capable of supplying the entire residential needs of the state.[12]

History[edit]

Non-hydraulic fracturing[edit]

Fracturing as a method to stimulate shallow, hard rock oil wells dates back to the 1860s. Oil producers in Pennsylvania, New York, Kentucky, and West Virginia used nitroglycerin (liquid at first, and later solid) to break up the oil-bearing formation. The method was later applied to water and natural gas wells.[1] The idea of using acid as a nonexplosive fluid for well stimulation was introduced in the 1930s. Acid etching kept fractures open and enhanced productivity. Water injection and squeeze cementing (injection of cement slurry) had a similar effect.[1]

Quarrying[edit]

The first industrial use of hydraulic fracturing was as early as 1903, according to T.L. Watson of the U.S. Geological Survey.[13] Before that date, hydraulic fracturing was used at Mt. Airy Quarry, near Mt Airy, North Carolina where it was (and still is) used to separate granite blocks from bedrock.[citation needed]

Oil and gas wells[edit]

The relationship between well performance and treatment pressures was studied by Floyd Farris of Stanolind Oil and Gas Corporation. This study became a basis of the first hydraulic fracturing experiment, which was conducted in 1947 at the Hugoton gas field in Grant County of southwestern Kansas by Stanolind.[1][14] For the well treatment 1,000 US gallons (3,800 L; 830 imp gal) of gelled gasoline and sand from the Arkansas River was injected into the gas-producing limestone formation at 2,400 feet (730 m). The experiment was not very successful as deliverability of the well did not change appreciably. The process was further described by J.B. Clark of Stanolind in his paper published in 1948. A patent on this process was issued in 1949 and an exclusive license was granted to the Halliburton Oil Well Cementing Company. On March 17, 1949, Halliburton performed the first two commercial hydraulic fracturing treatments in Stephens County, Oklahoma, and Archer County, Texas.[1] The practice caught on quickly, and in June 1950, Newsweek reported that 300 oil wells had been treated with the new technique.[15] In 1965, a US Bureau of Mines publication wrote of hydraulic fracturing: "Many fields are in existence today because of these fracturing techniques for, without them, many producing horizons would have been bypassed in the past 15 years as either barren or commercially nonproductive."[16]

Massive hydraulic fracturing[edit]

In the 1960s, American geologists became increasingly aware of huge volumes of gas-saturated rocks with permeability too low (generally less than 0.1 millidarcy) to recover the gas economically. The US government experimented with using underground nuclear explosions to fracture the rock and enable gas recovery from the rock. Such explosions were tried in the San Juan Basin of New Mexico (Project Gasbuggy, 1967), and the Piceance Basin of Western Colorado (Project Rulison, 1969, and Project Rio Blanco, 1973) but the results were disappointing, and the tests were halted. The petroleum industry turned to the new massive hydraulic fracturing technique as the way to recover tight gas.[17]

The definition of a massive hydraulic fracturing varies somewhat, but is generally used for treatments injecting greater than about 300,000 pounds of proppant (136 tonnes).[17] Pan American Petroleum applied the first massive hydraulic fracturing (also known as high-volume hydraulic fracturing) treatment in the world to a well in Stephens County, Oklahoma in 1968. The treatment injected half a million pounds of proppant into the rock formation.[1]

In 1973, Amoco introduced massive hydraulic fracturing to the Wattenberg Gas Field of the Denver Basin of Colorado, to recover gas from the low-permeability J Sandstone. Before massive hydraulic fracturing, the Wattenberg field was uneconomic. Injected volumes of 132,000 or more gallons, and 200,000 or more pounds of sand proppant, succeeded in recovering much greater volumes of gas than had been previously possible.[18] In 1974, Amoco performed the first million-pound frac job, injecting more than a million pounds of proppant into the J Sand of a well in Wattenberg Field.[19]

The success of massive hydraulic fracturing in the Wattenberg Field of Colorado was followed in the late 1970s by its use in gas wells drilled to tight sandstones of the Mesaverde Group of the Piceance Basin of western Colorado.[20]

Starting in the 1970s, thousands of tight-sandstone gas wells in the US were stimulated by massive hydraulic fracturing. Examples of areas made economic by the technology include the Clinton-Medina Sandstone play in Ohio, Pennsylvania, and New York; the San Juan Basin in New Mexico and Colorado; numerous fields in the Green River Basin of Wyoming; and the Cotton Valley Sandstone trend of Louisiana and Texas.[17]

Coalbed methane wells[edit]

Coalbed methane wells, which first began to be drilled in the 1980s, are commonly hydraulically fractured to increase the flow rates to the well. Hydraulic fracturing is commonly used in some coalbed methane areas, such as the Black Warrior Basin and the Raton Basin, but not in others, such as the Powder River Basin, depending on the local geology. Injected volumes tend to be much smaller than those of either tight gas wells or shale gas wells; a 2004 EPA study found a median injected volume of 57,500 US gallons (218,000 L; 47,900 imp gal) for coalbed methane wells.[21]

Horizontal wells[edit]

The combination of horizontal drilling and multistage hydraulic fracturing was pioneered in Texas’ Austin Chalk play in the 1980s. Stephen Holdich, head of the Department of Petroleum Engineering at Texas A&M University, commented: “In fact, the Austin Chalk is the model for modern shale development methods.”[22] The Austin Chalk play started in 1981 with vertical wells, but died with the decline in the oil price in 1982. In 1983, Maurer Engineering designed the equipment to drill the first medium-range horizontal well in the Austin Chalk. Horizontal drilling revived the play by increasing production, and lengths of the horizontal parts of the wellbores grew with greater experience and improvements in drilling technology. Union Pacific Resources, later acquired by Anadarko Petroleum, entered the Austin Chalk play in a major way in 1987, and drilled more than a thousand horizontal wells in the Austin Chalk, with multistage massive slickwater hydraulic fracture treatments, making major improvements in drilling and fracturing techniques.[23][24]

Shales[edit]

Hydraulic fracturing of shales goes back at least to 1965, when some operators in the Big Sandy gas field of eastern Kentucky and southern West Virginia started hydraulically fracturing the Ohio Shale and Cleveland Shale, using relatively small fracs. The frac jobs generally increased production, especially from lower-yielding wells.[25]

From 1976 to 1992 the United States government funded the Eastern Gas Shales Project, a set of dozens of public-private hydro-fracturing pilot demonstration projects. The program made a number of advances in hydraulic fracturing of shales.[2] During the same period, the Gas Research Institute, a gas industry research consortium, received approval for research and funding from the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission.[26]

In 1997, Nick Steinsberger, an engineer of Mitchell Energy (now part of Devon Energy), applied the slickwater fracturing technique, using more water and higher pump pressure than previous fracturing techniques, which was used in East Texas by Union Pacific Resources, in the Barnett Shale of north Texas.[27] In 1998, the new technique proved to be successful when the first 90 days gas production from the well called S.H. Griffin No. 3 exceeded production of any of the company's previous wells.[28][29] This new completion technique made gas extraction widely economical in the Barnett Shale, and was later applied to other shales.[30][31][32] George P. Mitchell has been called the "father of fracking" because of his role in applying it in shales.[33] The first horizontal well in the Barnett Shale was drilled in 1991, but was not widely done in the Barnett until it was demonstrated that gas could be economically extracted from vertical wells in the Barnett.[27]

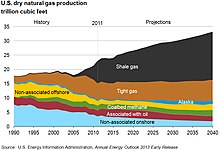

Between 2005 and 2010 the shale-gas industry in the United States grew by 45% a year. As a proportion of the country's overall gas production, shale gas increased from 4% in 2005 to 24% in 2012.[34]

According to oilfield services company Halliburton, as of 2013 more than 1.1 million hydraulic fracturing jobs have been done in the United States (some wells are hydraulically fractured more than once), and almost 90% of new US onshore oil and gas wells are hydraulically fractured.[35]

Typical extraction process[edit]

The process of extracting shale oil or gas typically has several stages, including some legal preliminaries. First, a company must negotiate the mineral rights with the owners.[36]: 44

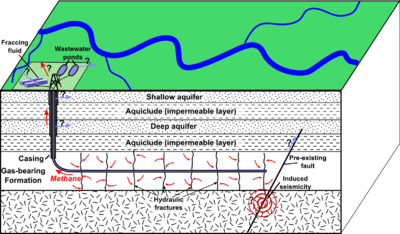

After a company has leased the mineral rights, it must obtain a permit to drill a well.[36]: 44 Permits are regulated by state agencies and the requirements vary.[37] Once it has obtained the permit, the company clears an area of 4–5 acres for a stage bed; it may also construct roads, a waste water site, and a temporary gas storage facility. Next is the drilling and casing of the well. In a process similar to that for constructing water wells, a bore machine drills vertically in the ground, and two or more steel casings are set in the well in a reverse telescope manner.[38] The casing helps keep the well open by providing structural support and preventing fluid and gas flow into the surrounding ground. Once the casing is in place, cement is pumped down inside the casing and back up on the outside of the casing. This is done to cement the casing in the formation and to prevent any leakage or flow of the gas and fluids behind the casing.[39]

The next step is the fracturing itself. A mixture of water and chemical additives are pumped down the well at high pressure. This creates fractures in the rock, and a proppant such as sand is injected to keep the fracture open. This allows the natural gas to flow to the well and up to the surface. The fracturing phase takes a few days,[36] and the recovery enhancement success of the fracturing job depends on a number of in-situ and operational parameters.[40]

After all this preparation, the well has a few years of production where natural gas is brought to the surface, treated, and carried off. This may be punctuated by workovers during which the well is cleaned and maintained to increase production. When the well has been exhausted, it is plugged. The area around it is restored to the level required by state standards and the agreement with the owner.[36]

Economic impact[edit]

Hydraulic fracturing of tight oil and shale gas deposits has the potential to alter the geography of energy production in the US.[41][better source needed][42] In the short run, in counties with hydrofracturing employment in the oil and gas sector more than doubled in the last 10 years, with spill-overs in local transportation, construction, and manufacturing sectors.[41][better source needed] The manufacturing sector benefits from lower energy prices, giving the US manufacturing sector a competitive edge. On average, natural gas prices have decreased by more than 30% in counties above shale deposits compared to the rest of the US. Some research has highlighted the negative effects on house prices for properties in the direct vicinity of fracturing wells.[43] Local house prices in Pennsylvania decrease if the property is close to a hydrofracking gas well and is not connected to city water, suggesting that the concerns of ground water pollution are priced by markets.

Oil and gas supply[edit]

The National Petroleum Council estimates that hydraulic fracturing will eventually account for nearly 70% of natural gas development in North America.[45] In 2009, the American Petroleum Institute estimated that 45% of the United States natural gas production and 17% of oil production would be lost within 5 years without usage of hydraulic fracturing.[46]

Of US gas production in 2010, 26% came from tight sandstone reservoirs and 23% from shales, for a total of 49%.[47] As production increased, there was less need for imports: in 2012, the US imported 32% less natural gas than it had in 2007.[48] In 2013, the US Energy Information Administration projected that imports will continue to shrink and the US will become a net exporter of natural gas some time around 2020.[49]

Increased US oil production from hydraulically fractured tight oil wells was mostly responsible for the decrease in US oil imports since 2005 (decreased oil consumption was also an important component). The US imported 52% of its oil in 2011, down from 65% in 2005.[50] Hydraulically fractured wells in the Bakken, Eagle Ford, and other tight oil targets, enabled US crude oil production to rise in September 2013 to the highest output since 1989.[51]

Proponents of hydraulic fracturing touted its potential to make the United States the world's largest oil producer and make it an energy leader,[52] a feat it achieved in November 2012 having already surpassed Russia as the world's leading gas producer.[53] Proponents say that hydraulic fracturing would give the United States energy independence.[54] In 2012, the International Energy Agency (IEA) projected that the United States, now the world's third-largest oil producer behind Saudi Arabia and Russia, will see such an increase in oil from shales that the US will become the world's top oil producer by 2020.[55] In 2011 the US became the world's leading producer of natural gas when it outproduced Russia. In October 2013, the US Energy Information Administration projected that the US had surpassed Russia and Saudi Arabia to become the world's leading producer of combined oil and natural gas hydrocarbons.[56]

Globally, gas use is expected to rise by more than 50% compared to 2010 levels, and account for over 25% of world energy demand in 2035.[57] Anticipated demand and higher prices abroad have motivated non-US companies to buy shares and invest in US gas and oil companies,[58][59] and in the case of the Norwegian company Statoil, to buy an American company with hydraulic fracturing expertise and US shale oil production.[60]

Some geologists say that the well productivity estimates are inflated and minimize the impact of the reduced productivity of wells after the first year or two.[61] A June 2011 New York Times investigation of industrial emails and internal documents found that the profitability of unconventional shale gas extraction may be less than previously thought, due to companies intentionally overstating the productivity of their wells and the size of their reserves. The same article said, "Many people within the industry remain confident." Financier T. Boone Pickens said that he was not worried about shale companies and that he believed they would make good money if prices rise. Pickens also said that technological advances, such as the repeated hydraulic fracturing of wells, was making production cheaper. Some companies that specialize in shale gas have shifted to areas where the gas in natural gas liquids such as propane and butane.[62][63] The article was criticized by, among others, The New York Times' own public editor for lack of balance in omitting facts and viewpoints favorable to shale gas production and economics.[64]

Gas price[edit]

According to the World Bank, as of November 2012, the increased gas production due to horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing in the US had driven US gas prices down to 29% of natural gas prices in Europe, and to one-fifth of natural gas prices in Japan.[65] Lower natural gas prices in the US have encouraged the replacement of coal- with gas-fired power plants, but have also discouraged the switch to renewable sources of energy.[66] Facing a supply glut and consequent further price drops in 2012, some large US gas producers announced plans to cut natural gas production; however, production rates rose to all-time highs, and natural gas prices remained near ten-year lows.[67] The high price of gas overseas has provided a strong incentive for producers to export it.[68]

Exports[edit]

U.S.-based refineries have gained a competitive edge with their access to relatively inexpensive shale oil and Canadian crude. The U.S. is exporting more refined petroleum products, and also more liquified petroleum gas (LP gas). LP gas is produced from hydrocarbons called natural gas liquids, released by the hydraulic fracturing of petroliferous shale, in a variety of shale gas that's relatively easy to export. Propane, for example, costs around $620 a ton in the U.S. compared with more than $1,000 a ton in China, as of early 2014. Japan, for instance, is importing extra LP gas to fuel power plants, replacing idled nuclear plants. Trafigura Beheer BV, the third-largest independent trader of crude oil and refined products, said at the start of 2014 that "growth in U.S. shale production has turned the distillates market on its head".[69]

In 2012, the U.S. imported 3,135 billion cubic feet (88.8 billion cubic metres) of natural gas and exported 1,619 billion cubic feet (45.8 billion cubic metres). Of the exports, 1,591 billion cubic feet (45.1 billion cubic metres) was sent by pipeline to Canada and Mexico; 18 billion cubic feet (510 million cubic metres) was re-exports of foreign shipments (bought at low prices and then held until the price went up); and the remaining 9.5 billion cubic feet (270 million cubic metres) was exported as liquefied natural gas (LNG) – natural gas that has been liquefied by cooling to about −161 degrees Celsius, reducing the volume by a factor of 600.[70]

The US has two export terminals: one owned by Cheniere Energy in Sabine Pass, Louisiana, and a ConocoPhillips terminal in North Cook Inlet, Alaska.[68] Companies that wish to export LNG must pass a two-step regulatory process required by the Natural Gas Act of 1938. First, the United States Department of Energy (DOE) must certify that the project is consistent with the public interest. This approval is automatic for export to the twenty countries that have a free trade agreement with the United States.[70][71] Applications for export to non-FTA countries are published in the Federal Register and public comment is invited; but the burden of proof for any public harm rests with opponents of the application, so opposition by groups such as the Sierra Club[72] has so far not blocked any approvals.[70] In addition, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) must conduct an environmental review and approve the export facility. As of 2013, only one facility – the Sabine Pass terminal in Cameron Parish, Louisiana, run by Cheniere Energy – had both DOE and FERC approval and was under construction. Three others – Trunkline LNG in Lake Charles, Louisiana; Dominion Cove Point LNG in Lusby, Maryland; and a terminal in Freeport, Texas – have DOE approval and await FERC approval.[70] On January 30, 2014, Cheniere Energy signed an agreement to supply 3.5 million tons to Korean Gas Corporation.[73]

A partnership of three companies (UGI Corporation, Inergy Midstream L.P. and Capitol Energy Ventures) has proposed building a new pipeline connecting the Marcellus Shale formation with markets in Pennsylvania and Maryland.[74][75][76] The pipeline would also supply LNG export terminals in Maryland.[73]

Critics have charged that exporting LNG could threaten the national energy security provided by gas from hydraulically fractured shale gas wells.[73]

Because of its carbon intensity, taking into account its lifecycle emissions, the IEA's Net Zero Emissions road map, projects a rapid collapse in the trade of liquified natural gas, if the world implements the Paris Agreement.[77]

Jobs[edit]

Economic effects of hydraulic fracturing include increases in jobs and by extension and increases in business. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) states that it is unclear on a local level how and for how long hydraulic fracturing affects a community economically. It is hypothesized that hydraulic fracturing may not provide jobs to local communities due to the specialized nature of hydraulic fracturing tasks. Also, communities’ local resources could potentially be taxed due to the increase in industry traffic or if an accident occurs.[78] According to Benson (2016), siting a study completed by The U.S. Chamber of Commerce's Institute for 21st Century Energy, a fracking ban in the United States would result in 14.8 million jobs being cut by the year 2022. A potential ban would lead to a $4000 increase in the cost of living for a family, gas and electricity prices would rise by 400 percent, household income would drop by $873 billion and the gross domestic product would fall by $1.6 trillion.[79]

Property owners[edit]

In most countries mineral rights belong to the government, but in the United States the default ownership is fee simple, meaning that a land owner also has the rights to the subsurface and the air above the property.[80] However, the Stock-Raising Homestead Act of 1916 split the ownership, reserving mineral rights for the federal government in large parts of western states. The owners of the rights can also choose to split the rights.[81] Since the hydraulic fracturing boom started, home builders and developers – including D. R. Horton, the nation's biggest home builder; Ryland Homes; Pulte Homes; and Beazer Homes USA – have retained the subsurface rights to tens of thousands of homes in states where shale plays exist or are possible. In most states, they are not legally required to disclose this, and many of the home buyers are unaware they do not own the mineral rights.[82] Under split estate law, the surface owner must allow the mineral rights owner reasonable access. Protections for the surface owner vary; in some states an agreement is required that compensates them for the use of the land and reclaims the land after extraction is complete.[36]: 45

Since the presence of oil or gas is uncertain, the company usually signs a lease with a signing bonus and a percentage of the value at the wellhead as a royalty.[80] Concerns have been raised regarding the terms and clarity of the leases energy companies are signing with landowners, as well as the manner in which they are sold and the tactics used by companies in implementing them.[83]

A well on one property can drain oil or gas from neighboring properties, and horizontal drilling can facilitate this. In some parts of the U.S., the rule of capture gives the landowner rights to any resources they extract from their well.[84]: 21 Other states have unitization rules for sharing royalties based on the geometries of the reservoir and the property lines above it.[80]

A lease of oil and gas rights violates the terms of many mortgage agreements, including those used by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, because it devalues the property and allows hazardous materials on the property. As a result, some banks are refusing to make mortgages on land if with such a lease.[85][86][87]

Nationwide Insurance does not cover hydraulic fracturing related damage because it considered the risks of problems like water contamination made the financial exposure too great. However, to date there have been no substantial claims that targeted companies other than those owning or operating wells.[88]

Environmental and health impact[edit]

Potential environmental effects of hydraulic fracturing include contamination of ground water, risks to air quality, the potential migration of gases and hydraulic fracturing chemicals to the surface, the potential mishandling of waste, and the resulting effects on health such as an increased rate of cancer[89][90] and related environmental contamination.[91][92][93][94][95]

While gas drilling companies are reluctant to reveal the proprietary substances in the fluid,[96] the list of additives for hydraulic fracturing includes kerosene, benzene, toluene, xylene, and formaldehyde.[97] It has been predicted that exposure to chemicals in hydraulic fracturing fluid will increase as gas wells using this technology proliferate.[90]

In April 2011, the Ground Water Protection Council (GWPC) launched FracFocus.org, an online voluntary disclosure database for hydraulic fracturing fluids. The site is funded by oil and gas trade groups and the DOE. The site has been met with some skepticism[98] relating to proprietary information that is not included, although Heather Zichal, former advisor to President Barack Obama, said of the database: “As an administration, we believe that FracFocus is an important tool that provides transparency to the American people.”[99] At least five states, including Colorado[100] and Texas, have mandated fluid disclosure[101] and incorporated FracFocus as the tool for disclosure. As of March 2013, FracFocus had more than 40,000 searchable well records on its site.

The FracTracker Alliance, a non-profit organization, provides oil and gas-related data storage, analyses, and online and customized maps related to hydraulic fracturing. Their website, FracTracker.org, also includes a photo library and resource directory. [102][103]

EPA hydraulic fracturing study[edit]

In 2010 Congress requested that EPA undertake a new, broader study of hydraulic fracturing. The report was released in 2015.[104] The purpose of the study was to examine the effects of hydraulic fracturing on the water supply, specifically for human consumption. The research aims to examine the full scope of the water pathway as it moves through the hydraulic fracturing process, including water that is used for the construction of the wells, the fracturing mixture, and subsequent removal and disposal. Fundamental research questions include:[105]

- How might large volume water withdrawals from ground and surface water impact drinking water resources?

- What are the possible impacts of releases of flowback and produced water on drinking water resources?

- What are the possible impacts of inadequate treatment of hydraulic fracturing wastewaters on drinking water resources?

The EPA Science Advisory Board (SAB) reviewed the study plan in early March 2011. In June 2011, EPA announced the locations of its five retrospective case studies, which will examine existing hydraulic fracturing sites for evidence of drinking water contamination. They are:[106]

- Bakken Shale – Kildeer, and Dunn Counties, North Dakota

- Barnett Shale – Wise and Denton Counties, Texas (Hydraulic Fracturing is currently banned in Denton County as of November 4, 2014)

- Marcellus Shale – Bradford and Susquehanna Counties, Pennsylvania

- Marcellus Shale – Washington County, Pennsylvania

- Raton Basin (coalbed methane) – Las Animas County, Colorado

Dr. Robin Ikeda, deputy director of Noncommunicable Diseases, Injury and Environmental Health at the CDC noted that none of the following EPA investigation sites were included in the final version of EPA's Study of the Potential Impacts of Hydraulic Fracturing on Drinking Water Resources: Dimock, Pennsylvania; LeRoy, Pennsylvania; Pavillion, Wyoming; Medina, Ohio; Garfield County, Colorado.[107]

The completed report draft was posted in 2015 and is available on the EPA website.[108] The report concluded that while very few cases of water contamination have been found relative to the abundance of fracking, there are several concerns for potential contamination in the future. The report was not regulatory in nature but instead was created to inform local governments, the public, and industry, of current data for use in future decision making.

A majority of the EPA SAB advised the agency to scale back proposed toxicity testing of fracking chemicals, and not pursue development of tracer chemicals to be added to frack treatments, because of time limitations. Chesapeake Energy agreed with the recommendation.[109] The SAB advised EPA to delete proposed toxicity tests from the study scope, due to limited time and funds.[110] However, some members of the SAB urged the board to advise the EPA to reinstate the toxicity testing of hydraulic fracturing chemicals.[109] Chesapeake Energy agreed,[111] stating “an in-depth study of toxicity, the development of new analytical methods and tracers are not practical given the budget and schedule limitation of the study.”[109] Thus, despite concerns about the elevated levels of iodine-131 (a radioactive tracer used in hydraulic fracturing) in drinking water in Philadelphia and Pittsburgh, downstream from hydraulic fracturing sites,[112][113][114][115] iodine-131 is not listed among the chemicals to be monitored in the draft plan for the study. Other known radioactive tracers used in hydraulic fracturing[116][117][118] but not listed as chemicals to be studied include isotopes of gold, xenon, rubidium, iridium, scandium, and krypton.[119]

Water use[edit]

Hydraulic fracturing uses between 1.2 and 3.5 million US gallons (4,500 and 13,200 m3) of water per well, with large projects using up to 5 million US gallons (19,000 m3). Additional water is used when wells are refractured.[120][121] An average well requires 3 to 8 million US gallons (11,000 to 30,000 m3) of water over its lifetime.[121][122][123][124]

According to Environment America, a federation of state-based, citizen-funded environmental advocacy organizations, there are concerns for farmers competing with oil and gas for water.[125] A report by Ceres questions whether the growth of hydraulic fracturing is sustainable in Texas and Colorado as 92% of Colorado wells were in extremely high water stress regions (that means regions where more than 80% of the available water is already allocated for agricultural, industrial and municipal water use) and 51% percent of the Texas wells were in high or extremely high water stress regions.[126]

Consequences for agriculture have already been observed in North America. Agricultural communities have already seen water prices rising because of that problem.[127] In the Barnett Shale region, in Texas and New Mexico, drinking water wells have dried as hydraulic fracturing water has been taken from an aquifer used for residential and agricultural use.[127]

Two types of water are produced after the injection of the fracturing fluid; the "flow-back" fluid which returns right after the fracking fluid is injected, and the "produced water" which returns to the surface over the lifespan of the well. Both by-products contain gas and oil as well as heavy metals, organic matter, salts, radioactive materials and other

chemicals.[128] The treatment of produced water is very critical since it contains "hazardous organic and inorganic constituents".[129] Some organic detected compounds are polyaromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), aliphatic hydrocarbons and long chain fatty acids. The chemical compounds related to HF are ethoxylated surfactants and the biocide 1,2,5trimethylhexahydro-1,3,5-triazine-2-thione (a dazomet derivative).[130]

The majority of the by-product is disposed in reinjection on designated wells, but since they are limited and located far from the hydraulic wells alternative solutions have been implemented for example the excavation of pits, on side water tanks, local treatment plants, the spread over fields and roads, and the treatment for further reuse of the water for HF extractions.[131] However, limited research has been conducted on the microbial ecology of this byproduct to determine the future impact on the environment.[132]

The treatment of the byproduct varies from well to well since the mixed fluids, and the geological formations around the wells are not the same. Therefore, most wastewater treatment plants (WWTP), besides being confronted with high volatile compounds, need to treat high saline wastewaters, which pose a problem since desalination of water requires large amounts of energy.[133] Therefore, the university of Arkansas has conducted promising research in which the combination of electrocoagulation (EC) and forward osmosis (FO) is used for the treatment of produced water resulting in an energy effective removal in suspended solids and organic contaminants, resulting in a 21% increase in water reuse.[129]

Well blowouts and spills of fracturing fluids[edit]

A well blowout in Clearfield County, Pennsylvania on June 3, 2010, sent more than 35,000 gallons of hydraulic fracturing fluids into the air and onto the surrounding landscape in a forested area. Campers were evacuated and the company EOG Resources and the well completion company C.C. Forbes were ordered to cease all operations in the state of Pennsylvania pending investigation. The Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection called it a "serious incident".[134][135]

Fluid injection and seismic events[edit]

Injection of fluid into subsurface geological structures, such as faults and fractures, reduces the effective normal stress acting across these structures. If sufficient shear stress is present, the structure may slip in shear and generate seismic events over a range of magnitudes; natural gas drilling may have caused earthquakes in North Texas.[136] Reports of minor tremors of no greater than 2.8 on the Richter scale were reported on June 2, 2009, in Cleburne, Texas, the first in the town's 140-year history.[137]

In July 2011, the Arkansas Oil and Gas Commission voted to shut down four produced water disposal wells, and to impose a permanent moratorium on Class II disposal wells in a faulted area of Faulkner, Van Buran, and Cleburne counties which has experienced numerous earthquakes.[138][139] The U.S. Geological Survey is working on ways to avoid quakes from wastewater disposal wells.[140]

In 2014, Oklahoma had 585 earthquakes with a magnitude of 3.0 or greater. Between the years 1978 and 2008 the state averaged 1.6 quakes of these magnitudes a year. The quakes are very likely related to the deep injection of oil and gas wastewater, a significant portion of which comes from wells which have been hydraulically fractured.[141] The fluid travels underground, often changing the pressure on fault lines.[142][143][144] The Oklahoma Corporation Commission later put in place regulations of waste water injection to limit the induced earthquakes.[145][146]

Fluid withdrawal and land subsidence[edit]

Subsidence (the sinking of land) may occur after considerable production of oil or ground water. Oil, and, less commonly, gas extraction, has caused land subsidence in a small percentage of fields. Significant subsidence has been observed only where the hydrocarbon reservoir is very thick, shallow, and composed of loose or weakly cemented rock.[147] In 2014, the British Department of Energy and Climate change noted that there are no documented cases of land subsidence connected with hydraulic fracturing, and that land subsidence due to extraction from shale is unlikely, because shale is not easily compressed.[148]

Air and health[edit]

Many particulates and chemicals can be released into the atmosphere during the process of hydraulic fracturing, such as sulfuric oxide, nitrous oxides, volatile organic compounds (VOC), benzene, toluene, diesel fuel, and hydrogen sulfide (H

2S), all of which can have serious health implications. A study conducted between August 2011 and July 2012 as part of Earthworks’ Oil & Gas Accountability Project (OGAP) found chemical contaminants in the air and water of rural communities affected by the Shale extraction process in central New York and Pennsylvania. The study found disproportionately high numbers of adverse health effects in children and adults in those communities.[149]

A potential hazard that is commonly overlooked is the venting of bulk sand silos directly to atmosphere. When they are being filled, or emptied during the fracture job, a fine cloud of silica particulate will be vented directly into atmosphere. This dust has the potential to travel many kilometers on the wind directly into populated areas. While the immediate personnel are wearing personal protective equipment, other people in the area of a well fracture can potentially be exposed.[150][unreliable source]

A 2012 study out of Cornell's College of Veterinary Medicine by Robert Oswald, a professor of molecular medicine at Cornell's College of Veterinary Medicine, and veterinarian Michelle Bamberger, DVM, soon to be published in 'New Solutions: A Journal of Environmental and Occupational Health Policy,' suggests that hydraulic fracturing is sickening and killing cows, horses, goats, llamas, chickens, dogs, cats, fish and other wildlife, as well as humans. The study covered cases in Colorado, Louisiana, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania and Texas.[96] The case studies include reports of sick animals, stunted growth, and dead animals after exposure to hydraulic fracturing spills from dumping of the fluid into streams and from workers slitting the lining of a wastewater impoundment (evaporation ponds) so that it would drain and be able to accept more waste. The researchers stated that it was difficult to assess health impact because of the industry's strategic lobbying efforts that resulted in legislation allowing them to keep the proprietary chemicals in the fluid secret, protecting them from being held legally responsible for contamination. Bamberger stated that if you don't know what chemicals are, you can't conduct pre-drilling tests and establish a baseline to prove that chemicals found postdrilling are from hydraulic fracturing.[96] The researchers recommended requiring disclosure of all hydraulic fracturing fluids, that nondisclosure agreements not be allowed when public health is at risk, testing animals raised near hydraulic fracturing sites and animal products (milk, cheese, etc.) from animal raised near hydraulic fracturing sites prior to selling them to market, monitoring of water, soil and air more closely, and testing the air, water, soil and animals prior to drilling and at regular intervals thereafter.[96]

CNN has reported flammable tap water in homes located near hydraulic fracturing sites in Portage County, Ohio.[151] On October 18, 2013, the Ohio Department of Natural Resource-Division of Oil & Gas Resources Management found that the Kline's pre-drilling water sample showed methane was present in August 2012 before gas wells were drilled near their home. The report further states the gas was microbial in origin and not thermogenic like gas produced from gas wells.[152] Research done by the ODNR found that naturally occurring methane gas was present in the aquifers of Nelson and Windham Townships of Portage County, Ohio.[152]

A 2014 study of households using groundwater near active natural gas drilling in Washington County, Pennsylvania found that upper respiratory illnesses and skin diseases were much more prevalent closer to hydraulic fracturing activity. Respiratory problems were found in 18% of the population 1.2 miles or more from drilling, compared to 39% of those within 0.6 miles of new natural gas wells. People with clinically significant skin problems increased from 3% to 13% over the same distances.[153]

Methane leakage is one hazard associated with hydraulic fracturing natural gas. Methane is a prominent greenhouse gas. Over a twenty-year period, it is 72 times more potent than carbon dioxide.[154] In 2012 it accounted for 9% of all US greenhouse gas emissions. Natural Gas and Petroleum Systems are the largest contributor, providing 29% of the emissions.[155] Natural gas drilling companies are beginning to incorporate technologies called green completion to minimize methane leakage.[154]

The indirect effects of the increase in the supply of natural gas from fracking have only recently started to be measured. A 2016 study of air pollution from coal generation in the US found that there may have been indirect benefits from fracking through the displacement of coal by natural gas as an energy source. The increase in fracking from 2009 led to a drop in natural gas prices that made natural gas become more competitive with coal. This analysis estimates coal generation decreased as a result by 28%, which led to an average reduction of 4% in air pollution yielding positive health benefits. However, this is only the case in the US and may not be applicable to other countries with lower coal generation rates.[156]

Impacts on human health[edit]

The evidence about the potential detrimental health effects as a result of fracking have been mounting; threatening the well-being of humans, animals and our environment. These pollutants, even when exposed to at low levels, can lead to a multitude of both short and long term symptoms. Many of these health consequences start off as acute issues, but due to long term exposure turn into chronic diseases. Volatile organic compounds and diesel particulate matter, for example, result in elevated air pollution concentrations that exceed EPA guidelines for both carcinogenic and noncarcinogenic health risks.[157]

According to the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC), cancer-causing pollutants such as benzene, formaldehyde, and diesel have been found in the air near fracking sites.[158] These pollutants generate wastewater, which is linked to groundwater contamination, threatening nearby drinking water and causing concern for anyone who is exposed. Studies done by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) found that “Fracking also uses crystalline silica, which is a type of sand that’s used to keep the fractures open.” [159] Exposure to this, along with dust and other air pollutants produced from fracking, can cause respiratory problems.

One of the most common types of pollutants released into the air from fracking is methylene chloride, thought to be one of the most concerning due to its potentially severe impact on neurological functioning. Once again, the impacts can range from acute and moderate to chronic and more severe. Dizziness, headaches, seizures and loss of consciousness have all been observed in people exposed to this deadly chemical. Longer-term impacts tend to present themselves in areas such as memory loss, lower IQ and delayed mental development.[160]

Expecting mothers are also being cautioned. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons released into the air from fracking has been linked to potential reproductive problems. A study conducted by the Colorado Department of Environmental and Occupational Health found that “Mothers who live near fracking sites are 30 percent more likely to have babies with congenital heart defects.”[161] The NRDC also claims there's the potential for “Harm to the developing heart, brain and nervous system. Because even short-term exposures to these pollutants at critical moments of development can result in long-lasting harm.”[158]

Despite researcher's knowledge about the adverse health effects these pollutants can have on humans and the environment, it's challenging to fully understand the direct health impacts that are a result from fracking and assess the potential long-term health and environmental effects. This is because the oil and gas industry is legally protected from disclosing what is in the chemical compounds they use for fracking.[162] “Policies are also lacking in requiring full health impact assessments to be required before companies are given the go-ahead to drill” [163]

Workplace safety[edit]

In 2013 the United States the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) and NIOSH released a hazard alert based on data collected by NIOSH that "workers may be exposed to dust with high levels of respirable crystalline silica (silicon dioxide) during hydraulic fracturing."[164] Crystalline silica is the basic component of many minerals including sand, soil, and granite, but the most common form is quartz. Inhaling respirable crystalline silica can cause silicosis, lung cancer, autoimmune disorders, kidney disease, and can increase the risk of tuberculosis. It is also classified as a known human carcinogen.[165][166] Out of the 116 air samples collected by NIOSH from 11 sites across 5 states, 47% showed silica exposures greater than the OSHA permissible exposure limit and 79% showed silica exposures greater than the NIOSH recommended exposure limit.[167]

NIOSH notified company representatives of these findings and provided reports with recommendations to control exposure to crystalline silica and recommend that all hydraulic fracturing sites evaluate their operations to determine the potential for worker exposure to crystalline silica and implement controls as necessary to protect workers.[168]

In addition to the hazard alert regarding exposure to respirable crystalline silica, OSHA released a publication entitled “Hydraulic Fracturing and Flowback Hazards Other than Respirable Silica,” in an attempt to further protect workers and better educate employers on a variety of additional hazards involved. The report includes hazards that may occur during transportation activities, rig-up and rig-down, mixing and injection, pressure pumping, flowback operations, and exposure to H

2S and VOCs.[169]

Transportation and rig-up/rig-down[edit]

Serious injury and death can occur during the various transportation activities of hydraulic fracturing. Well sites are often small and congested, with many workers, vehicles, and heavy machinery. This can increase the risk of injury or fatality. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Census of Fatal Occupational Injuries, from 2003 to 2009, work related vehicle crashes resulted in 206 worker fatalities.[170] Activities which may be hazardous include vehicle accidents while traveling to and from well sites, the delivery and movement of large machinery such as mixing or pumping equipment, and the rig-up/rig-down processes[169] In a study conducted in Pennsylvania, Muehlenbachs et al. found significant increases in total and heavy truck accidents in towns with hydraulic fracturing activity versus those without, with each well addition increasing rates of accidents by 2% and risk of fatality by .6%.[171] Rig-Up and Rig-Down are terms used to refer to the delivery, construction, dismantling and breakdown of equipment required throughout the hydraulic fracturing process. Incidents and fatalities during rig-up/rig-down operations may result if struck or crushed by the heavy equipment involved.[169]

Hazards during mixing and injection[edit]

Workers may be exposed to dangerous chemicals while mixing and injecting fluids used in hydraulic fracturing. Potential chemicals include, hydrochloric and hydrofluoric acid, biocides, methanol, ethylene glycol, guar gum, polysaccharides and polyacrylamides, magnesium peroxide, calcium peroxide, magnesium oxide, citric acid, acetic acid, sodium polycarboxylate, phosphonic acid, choline chloride, sodium chloride, formic acid, and lauryl sulfate. Effects of exposure to the chemicals listed vary in severity, but may include, chemical burns, skin and eye irritation, allergic reactions, carcinogenic effects, and toxic reactions from direct contact or inhalation of chemicals.[169]

Hazards during pressure pumping and flowback operations[edit]

Modern day fracking equipment is capable of pumping anywhere from 800 to 4200 gallons of water per minute, at pressures ranging from 500 to 20,000+ psi.[172] Once the injection process is complete and gas has entered the well, anywhere between 10 and 30 percent of the fluid injected will flow back into the well as wastewater for disposal. In addition to the chemical additives present in fracking fluid, flowback water contains dangerous volatile hydrocarbons, such as H

2S pulled from the fractured rock. Workers must use handheld gauges to check fluid levels via hatches on top of wells and when doing so they may be exposed to dangerous plumes of gas and vapor containing the volatile hydrocarbons. Exposure to these chemicals and hydrocarbons can affect the nervous system, heart rhythms, and may lead to asphyxiation or death.[173]

Additional workplace hazards[edit]

Spills[edit]

Workers are exposed to spills in the hydraulic fracturing process both on and offsite. Exposure to fluids involved in fluid spills (flowback water, fracking fluid, produced waters) also exposes nearby workers to any and all compounds, toxic or not, contained within those fluids.[171] Between 2009 and 2014, more than 21,000 individual spills were reported across the U.S., involving a total of 175 million gallons of wastewater.[174] Although using properly designed storage equipment at well sites protects against accidents such as spills, extreme weather conditions expose wells and make them vulnerable to spills regardless, exposing workers to additives, blended hydraulic fracturing fluids, flow back fluids and produced water, along with the hazardous materials therein.[171]

Explosions[edit]

According to the latest information available (collected in 2013), the Oil and Gas Industry has the highest number of fires and explosions of any private industry in the U.S. One of the greatest hazards faced by workers is during the pipeline repair process, which makes them vulnerable to flammable gas explosions. There currently exist very few training protocols for workers under these circumstances.[175]

Radioactive materials exposure[edit]

According to the EPA, unconventional oil and gas development is a source of technologically enhanced naturally occurring radioactive materials (TENORM).[176] The processes used in drilling, pumping water, and retrieving flow back and produced waters have the ability to concentrate naturally occurring radionuclides. These radioactive materials can be further concentrated in the wastes produced at the facilities and even in their products.[176] They can accumulate as scaling inside pipes or as sludge precipitating out of wastewater and expose workers to levels of radiation far higher than OSHA standards.[177] An OSHA hazard information bulletin suggested that “it is not unrealistic to expect (radioactive) contamination at all oil and gas production sites and pipe handling facilities”.[178] However, there are currently no steps being taken to protect employees from radiation exposure as far as TENORM is concerned because the EPA has exempted oil and gas waste from federal hazardous waste regulations under the RCRA (Resource Conservation and Recovery Act).[177]

Lawsuits[edit]

The natural gas industry has responded to state and local regulations and prohibitions with two primary types of lawsuits: preemption challenges, which argue that federal law prevents state governments from passing fracking restrictions, and Takings Clause challenges, which argue that the federal constitution entitles a company to compensation when a fracking ban or limitation renders that company's land useless.[179]

In September 2010, a lawsuit was filed in Pennsylvania alleging that Southwestern Energy Company contaminated aquifers through a defective cement casing in the well.[180] There have been other cases as well. After court cases concerning contamination from hydraulic fracturing are settled, the documents are sealed, and information regarding contamination is not available to researchers or the public. While the American Petroleum Institute deny that this practice has hidden problems with gas drilling, others believe it has and could lead to unnecessary risks to public safety and health.[4]

In June 2011, Northeast Natural Energy sued the town of Morgantown, West Virginia, for its ban on hydraulic fracturing in the Marcellus Shale within a mile of the town's borders. The ban had been initiated to protect the municipal water supply as well as the town's inhabitants, in the absence at the state level of regulations specific to hydraulic fracturing.[181]

Regulation[edit]

The number of proposed state regulations related to hydraulic fracturing has dramatically increased since 2005. The majority specifically address one aspect of natural gas drilling, for example wastewater treatment, though some are more comprehensive and consider multiple regulatory concerns.[182]

The regulation and implementation process of hydraulic fracturing is a complex process involving many groups, stakeholders, and impacts. The EPA has the power to issue permits for drilling and underground injection, and to set regulations for the treatment of waste at the federal level. However, the scope of its authority is debated, and the oil and gas industry is considering lawsuits if guidance from the EPA is overly broad. States are required to comply with federal law and the regulations set by the EPA. States, however, have the power to regulate the activities of certain companies and industries within their borders – they can create safety plans and standards, management and disposal regulations, and public notice and disclosure requirements. Land-use ordinances, production standards, and safety regulations can be set by local governments, but the extent of their authority (including their power to regulate gas drilling) is determined by state law.[183] Pennsylvania's Act 13 is an example of how state law can prohibit local regulation of hydraulic fracturing industries. In states including Ohio and New Mexico, the power to regulate is limited by trade secret provisions and other exemptions exist that preclude companies from disclosing the exact chemical content of their fluids.[184] Other challenges include abandoned or undocumented wells and hydraulic fracturing sites, regulatory loopholes in EPA and state policies, and inevitable limitations to the enforcement of these laws.[185]

Federal versus state regulation debate[edit]

Since 2012 there has been discussion whether fracking should be regulated at the state or federal level.[186][187] Advocates of state level control of energy sources (e.g., oil, gas, wind and solar), argue that a state-by-state approach allows each state to create regulations and review processes that fit each state's particular geological, ecological and citizen concerns.[187] Critics say that this would create a patchwork of inconsistent regulations.[186] They also note that the components and consequences of energy development (e.g., emissions, commerce, wastewater, earthquakes, and radiation) may cross state lines. Local and state governments may also lack resources to initiate and defend against corporate legal action related to hydraulic fracturing.[188][189]

Those supporting federal regulation think it will provide a more consistent, uniform standard[186] as needed for national environment and public health standards, like those related to water and air pollution (e.g., public disclosure of chemicals used in hydraulic fracturing, protection of drinking water sources, and control of air pollutants).[186][187] A compromise called, "cooperative federalism" has been proposed like an approach used for coal since 1977. Here, the federal government sets baseline standards rather than detailed specifications, and allows states to be more flexibile in meeting the standards. It would require the federal government to remove some regulatory exemptions for hydraulic fracturing (e.g., the Energy Policy Act of 2005, which exempted oil and gas producers from certain requirements of the Safe Drinking Water Act), and develop a comprehensive set of regulations for the industry.[186][190]

The EPA and the industry group the American Petroleum Institute each provided grants to fund the organization State Review of Oil and Gas Environmental Regulations (STRONGER), to promote better state oversight of oil and gas environmental issues. At the invitation of a state the organization reviews their oil and gas environmental regulations in general, and hydraulic fracturing regulations in particular, and recommends improvements. As of 2022 STRONGER has conducted initial reviews of hydraulic fracturing regulations in 24 states, accounting for over 90% of U.S. onshore production of oil and gas.[191][non-primary source needed]

Regulation at the state level of sets lower standard of regulations in terms of environmental issues than federal ones for different reasons. Firstly, states only have legislative power over their own territory so the potential areas affected by regulation may be more limited than the federal one. Related to that, the EPA has power over inter-state or boundary resources such as rivers, thus a broader regulative power. Secondly, environmental issues at the scale of states are usually related to energetic and economic issues through energy administrations, leaving the environmental impact often subsidiary to economic considerations, whereas the EPA's unique mandate concerns environmental issues, regardless of their economic or energetic aspect, since it is more independent from energy administrations.[192] State regulations are therefore considered to be generally weaker than federal ones. Thirdly, state-level policies are more subject to discreet political majority changes and lobbying whereas federal agencies theoretically work more independently from Congress and thus deliver more continuity in terms of policy-making.[192]

The academic literature has increasingly stressed often competing regulatory agendas of natural gas advocates and environmentalists.[192] Environmentalists and the supporters of a precautionary approach have advocated federal and powerful inter-state regulation as well as democratic empowerment of local communities. They have therefore supported inter-state organizations that gather state and federal actors such as the Delaware River Basin Commission when “natural gas policy” ones might not include federal actors. However, natural gas production advocates have favored state-level and weaker inter-state regulations and the withdrawal of regulatory powers such as zoning from local communities and institutions. They have only supported a subset of interstate organizations, typically those pledging support for weaker regulations and which do not include advocacy for regulatory powers such as the Interstate Oil and Gas Compact Commission.[192]

Proponents for state, rather than federal regulation argue that states, with local and historical knowledge of their unique landscapes, are better able to create effective policy than any standardized federal mandate. Congress as well as industry leaders have had a major impact on the regulatory exemptions of hydraulic fracturing and continue to be the dominant voice in determining regulation in the United States.

Federal[edit]

Hydraulic fracturing has known impacts on the environment and potential unknown direct or indirect impacts on the environment and human health. It is therefore part of the EPA's area of regulation. The EPA assures surveillance of the issuance of drilling permits when hydraulic fracturing companies employ diesel fuel. This is its main regulatory activity but it has been importantly reduced in its scope by the Energy Policy Act of 2005 that excluded hydraulic fracturing from the Safe Drinking Water Act’s Underground Injection Control’s regulation, except when diesel is used.[193] This has raised concerns about the efficiency of permit issuance control. In addition to this mission, the EPA works with states to provide safe disposal of wastewater from hydraulic fracturing, has partnerships with other administrations and companies to reduce the air emissions from hydraulic fracturing, particularly from methane employed in the process, and tries to ensure both compliance to regulatory standards and transparency for all stakeholders implied in the implementation process of hydraulic fracturing.

On August 7, 1997, the Eleventh Circuit Court ordered EPA to reevaluate its stance on hydraulic fracturing based on a lawsuit brought by the Legal Environmental Assistance Foundation. Until that decision, the EPA deemed that hydraulic fracturing did not fall under the rules in the Safe Drinking Water Act.[194] While the impact of this decision was localized to Alabama, it forced the EPA to evaluate its oversight responsibility under the Safe Drinking Water Act for hydraulic fracturing. In 2004, the EPA released a study that concluded the threat to drinking water from hydraulic fracturing was “minimal”. In the Energy Policy Act of 2005, Congress exempted fractured wells from being re-classified as injection wells, which fall under a part of the Safe Drinking Water Act that was originally intended to regulate disposal wells.[195][196] The act did not exempt hydraulic fracturing wells that include diesel fuel in the fracturing fluid. Some US House members have petitioned the EPA to interpret "diesel fuel" broadly to increase the agency's regulatory power over hydraulic fracturing. They argue that the current limitation is intended not to prevent the use of a small subset of diesel compounds, but rather as a safety measure to decrease the probability of accidental groundwater contamination with toxic BTEX chemicals (benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene and xylenes) that are present in diesel compounds.[197] Congress has been urged to repeal the 2005 regulatory exemption under the Energy Policy Act of 2005.[198] The FRAC Act, introduced in June 2009, would eliminate the exemption and might allow producing wells to be reclassified as injection wells placing them under federal jurisdiction in states without approved UIC programs.

In November 2012, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) was considering to study a potential link between fracturing and drinking water contamination. Republican House energy leaders advised Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Secretary Kathleen Sebelius to be cautious in the study. They argued the study, if not properly done, could hinder job growth. They worried that the study could label naturally occurring substances in groundwater as contaminants, that the CDC would limit hydraulic fracturing in the interest of public health, and that the "scientific objectivity of the [HHS] [wa]s being subverted" as the CDC was considering whether to study the question.[199][200]

Environmental Protection Agency Administrator Lisa Jackson said the EPA would use its power to protect residents if drillers endangered water supplies and state and local authorities did not take action.[201]

In March 2015, Democrats in Congress reintroduced a series of regulations known as the "Frack Pack". These regulations were imposed on the domestic petroleum industry. The package would regulate hydraulic fracturing under the Safe Drinking Water Act and require chemicals used in hydraulic fracturing fluid to be disclosed to the public. It would require pollution tests of water sources before and during petroleum development. It would require oil and gas producers to hold permits in order to increase stormwater runoff.[202] New regulations set safety standards for how used chemicals are stored around well sites and necessitate companies to submit information on their well geology to the Bureau of Land Management, an agency within the Interior Department.[203] The "Frack Pack" received criticism, especially from The Western Energy Alliance petroleum industry group, for duplicating state regulations that already existed.[202]

On January 22, 2016, the Obama administration announced new regulations for emissions from oil and gas on federal lands to be regulated by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) to decrease impacts made on global warming and climate change.[204] This became known as the “BLM fracking rule”, and would take effect on March 31 extending into Federal, Indian, and Public lands.[205] This rule would apply to more than 750 million areas of Federal and Indian lands and regulated chemical disclosure, well integrity, and flowback water management.[205] This rule would require companies to identify the chemicals being used in hydraulic fracturing and their purpose. This requirement would only extend to chemicals used after, not before, fracking to protect company chemical mix recipes.[206] But, not knowing the chemicals beforehand eliminates the government's ability to test the water for a baseline reading to know if the process is contaminating water sources or not. Well integrity is vital to ensure that oil, gas, and other fracking chemicals are not being leached into direct drinking water sources. The rule would require operators to submit a cement bond log to ensure that drinking water has been properly isolated from the water that will be used. Finally, the BLM requires companies to provide their estimated waste water totals along with a disposal plan.[207] The fracking rule was met with critiques for not requiring more transparency from corporations on chemicals being used before drilling into wells.[206]

On March 2, 2017, EPA announced that it was withdrawing its request that operators in the oil and natural gas industry provide information on equipment and emissions until further data is collected that this information is necessary.[208] On December 29, 2017, a 2015 BLM rule that would have set new environmental limitations on hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, on public lands was rescinded by the US Department of Interior.[209]

Fracturing Responsibility and Awareness of Chemicals Act[edit]

Congress has been urged to repeal the 2005 regulatory exemption under the Energy Policy Act of 2005 by supporting The FRAC Act, introduced in June 2009, but has so far refused.[198] In June 2009 two identical bills named the Fracturing Responsibility and Awareness of Chemicals Act were introduced to both the United States House and the Senate. The House bill was introduced by representatives Diana DeGette, D-Colo., Maurice Hinchey D-N.Y., and Jared Polis, D-Colo. The Senate version was introduced by senators Bob Casey, D-Pa., and Chuck Schumer, D-N.Y. These bills are designed to amend the Safe Drinking Water Act. This would allow EPA to regulate hydraulic fracturing that occurs in states which have not taken primacy in UIC regulation. The bill required the energy industry to reveal what chemicals are being used in the sand-water mixture. The 111th United States Congress adjourned on January 3, 2011, without taking any significant action on the FRAC Act. The FRAC Act was re-introduced in both houses of the 112th United States Congress. In the Senate, Sen. Bob Casey (D-PA) introduced S. 587 on March 15, 2011.[210] In the House, Rep. Diana DeGette (D-CO) introduced H.R. 1084 on March 24, 2011.[211] As of March 2012 Congress had not yet passed either of The FRAC Act bills.[212][213] The oil and gas industry contributes heavily to campaign funds.[214]

Federal lands[edit]

In May 2012, the Department of Interior released updated regulations on hydraulic fracturing, for wells on federal lands. However, Guggenheim Washington Research Group found that only about 5% of the shale wells drilled in the past 10 years were on federal land.[215]

Voluntary disclosure of additives[edit]

In April 2011, the GWPC, in conjunction with the industry, began releasing well-by-well lists of hydraulic fracturing chemicals at FracFocus.[216] Disclosure is still on a voluntary basis; companies are still not required to provide information about their hydraulic fracturing techniques and fluids that they consider to be proprietary.[217] Lists do not include all substances used; a complete listing of the specific chemical formulation of additives used in hydraulic fracturing operations is still not currently made available to landowners, neighbors, local officials, or health care providers, let alone the public. This practice is under scrutiny.[citation needed] Two studies released in 2009, one by the DOE and the other released by the GWPC, discuss hydraulic fracturing safety concerns.[citation needed] Chemicals which can be used in the fracturing fluid include kerosene, benzene, toluene, xylene, and formaldehyde.[89][218]

State and local[edit]

The controversy over hydraulic fracturing has led to legislation and court cases over primacy of state regulation versus the rights of local governments to regulate or ban oil and gas drilling. Some states have introduced legislation that limits the ability of municipalities to use zoning to protect citizens from exposure to pollutants from hydraulic fracturing by protecting residential areas. Such laws have been created in Pennsylvania, Ohio,[219] and New York.[220]

Local regulations can be a dominant force in enacting drilling ordinances, creating safety standards and production regulations, and enforcing particular standards. However, in many cases state law can intervene and dominate local law. In Texas, the Railroad Commission of Texas has the authority to regulate certain industries and the specifics of their safety standards and production regulations.[183] In this case, the state determined the zoning, permitting, production, delivery, and safety standards.

In New York, local land use laws are considered in state regulations, and in Pennsylvania, the state's Oil and Gas Act superseded all local ordinances purporting to regulate gas well operations.” [183] Additionally, Los Angeles in 2013 become the largest city in the US to pass a hydraulic fracturing moratorium.[221]

Opposition[edit]

New York[edit]

In November 2010, the New York State assembly voted 93 to 43, for a moratorium or freeze on hydraulic fracturing to give the state more time to undertake safety and environmental concerns.[222]

In September 2012, the Cuomo administration decided to wait until it completed a review of the potential public health effects of hydraulic fracturing before it allowed high-volume hydraulic fracturing in New York. State legislators, medical societies and health experts pressed Joseph Martens, commissioner of the State Department of Environmental Conservation, for an independent review of the health impacts of hydraulic fracturing by medical experts before any regulations were made final and drilling is allowed to start. Martens rejected commissioning an outside study. Instead, he appointed the health commissioner, Dr. Nirav Shah, to assess the department's analysis of the health effects closely and said Shah could consult qualified outside experts for his review.[223] A 2013 review focusing on Marcellus shale gas hydraulic fracturing and the New York City water supply stated, "Although potential benefits of Marcellus natural gas exploitation are large for transition to a clean energy economy, at present the regulatory framework in New York State is inadequate to prevent potentially irreversible threats to the local environment and New York City water supply. Major investments in state and federal regulatory enforcement will be required to avoid these environmental consequences, and a ban on drilling within the NYC water supply watersheds is appropriate, even if more highly regulated Marcellus gas production is eventually permitted elsewhere in New York State."[224] On December 17, 2014, Governor Cuomo announced a statewide ban on the drilling process, citing health risks, becoming the first state in the United States to issue such a ban.[225][226]

Municipal level[edit]

At the municipal level, some towns and cities in central New York state have moved to regulate drilling by hydraulic fracturing and its attendant effects, either by banning it within municipal limits, maintaining the option to do so in the future, or banning wastewater from the drilling process from municipal water treatment plants.[227]

New York City. The New York City watershed includes a large area of the Marcellus shale formation. The NYC Dept. of Environmental Protection's position: "While DEP is mindful of the potential economic opportunity that this represents for the State, hydraulic fracturing poses an unacceptable threat to the unfiltered water supply of nine million New Yorkers and cannot safely be permitted with the New York City watershed."[228]

Niagara Falls. Niagara Falls' City Council approved an ordinance that prohibits natural gas extraction in Niagara Falls, as well as the "storage, transfer, treatment or disposal of natural gas exploration and production wastes".[229] Elected officials there said that they didn't want their citizens, who experienced the Love Canal toxic waste crisis firsthand, to be guinea pigs for hydraulic fracturing, the new technology used in gas drilling operations.[229] City council member, Glenn Choolokian said, “We won’t let the temptation of millions of dollars in reward for out-of-town companies, corporations and individuals to be the driving force that puts the health and lives of our children and families at risk from the dangers of hydraulic fracturing and its toxic water. I will not take part in bringing another Love Canal to the City of Niagara Falls.”“Our once great city and all the families of Niagara Falls have been through so much over the years. With Love Canal alive in our memories we aren’t going to allow another environmental tragedy to happen in our city, not today, not ever,” said Glenn Choolokian.[229] Council Chairman Sam Fruscione said he was against selling out future generations of children for corporate greed. Rita Yelda of Food and Water Watch, pointed out that pollutants don't only affect Niagara's citizens, but those in communities downstream as well.[229]

Maryland[edit]

In 2012 Governor Martin O'Malley had issued a hold on applications to drill in western Maryland until a three-year study of hydraulic fracturing's environmental impacts was completed, thus creating a de facto moratorium. Delegate Heather Mizeur planned to introduce a bill formally banning hydraulic fracturing until state officials could determine whether it can be done without harming drinking water or the environment. The gas industry refused to fund the three-year study or any studies unless it received guarantees that it will eventually be able to drill for gas. It opposed a bill sponsored by Mizeur to fund a study with fees on gas drilling leases.[230] In March 2017, Maryland banned fracking and became the first state in the nation with proven gas reserves to do so.[7] In April 2017, Governor Larry Hogan signed the bill banning fracking.[231]

Vermont[edit]

Vermont's Act 152 has banned hydraulic fracturing in the exploitation and exploration of unconventional oil and gas as long as it is not demonstrated that it has no impact on the environment or public health.[232]

In February 2012, the Vermont House of Representatives passed a moratorium on hydraulic fracturing although the state had no frackable oil or gas reserves at that time.[233][234] On Friday, May 4, 2012, the Vermont legislature voted 103–36 to ban hydraulic fracturing in the state. On May 17, 2012, Governor Peter Shumlin (Democrat) signed the law making Vermont the first state to ban hydraulic fracturing preventatively. The bill requires the state's regulations be revised to prohibit injection well operators from accepting oil and natural gas drilling waste water from out of state.[235]

Support[edit]

Alaska[edit]

Hydraulic fracturing has been conducted at the North Slope and the Kenai Peninsula on the South coast of Alaska. Due to potential harm to Alaska's fragile environment, there have been hearings on new regulations for this type of oil extraction.

California[edit]

California is the fifth-largest crude oil producer in the US.[236] ABC noted on December 6, 2019, that concerning fracking permits and views of fossil fuel extraction in California, "the state is moving to ramp down oil production while Washington is expediting it. State officials are taking a closer look at the environmental and health threats – especially land, air and water contamination – posed by energy extraction, while Washington appears to have concluded that existing federal regulations sufficiently protect its sensitive landscapes as well as public health."[237]