| History of Florida |

|---|

|

|

|

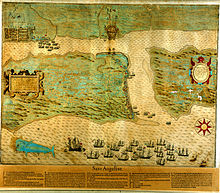

St. Augustine, Florida, the oldest continuously occupied settlement of European origin in the continental United States, was founded in 1565 by Spanish admiral Pedro Menéndez de Avilés. The Spanish Crown issued an asiento to Menéndez, signed by King Philip II on March 20, 1565, granting him various titles, including that of adelantado of Florida, and expansive privileges to exploit the lands in the vast territory of Spanish Florida, called La Florida by the Spaniards.[1] This contract directed Menéndez to explore the region's Atlantic coast and report on its features, with the object of finding a suitable location to establish a permanent colony from which the Spanish treasure fleet could be defended and Spain's claimed territories in North America protected against incursions by other European powers.[2]

Early exploration and attempts at settlement[edit]

The first European known to have explored the coasts of Florida was the Spanish explorer and governor of Puerto Rico, Juan Ponce de León, who likely ventured in 1513 as far north as the vicinity of the future St. Augustine, naming the peninsula he believed to be an island "La Florida" and claiming it for the Spanish crown.[3][4] Prior to the founding of St. Augustine in 1565, several earlier attempts at European colonization in what is now Florida were made by both Spain and France, but all failed.[5][6][7][8]

The French exploration of the area began in 1562, under the command of the Huguenot colonizer, Captain Jean Ribault. Ribault explored the St. Johns River to the north of St. Augustine before sailing further north up the Atlantic coast, ultimately founding the short-lived Charlesfort on what is now known as Parris Island, South Carolina. In 1564, Ribault's former lieutenant René Goulaine de Laudonnière headed a new colonization effort. Laudonnière explored St. Augustine Inlet and the Matanzas River, which the French named Rivière des Dauphins (River of Dolphins).[9] There they made contact with the local Timucua chief, Seloy, a subject of the powerful Saturiwa chiefdom,[10][11][12] before heading north to the St. Johns River. There they established Fort Caroline.[13]

Later that year a group of mutineers from Fort Caroline fled the colony and turned pirate, attacking Spanish vessels in the Caribbean. The Spanish used this as a pretext to locate and destroy Fort Caroline, fearing it would serve as a base for future piracy, and wanting to discourage further French colonization. King Philip II of Spain quickly dispatched Pedro Menéndez de Avilés to go to Florida and establish a center of operations from which to attack the French.[14][15]

Founding[edit]

Pedro Menéndez's ships first sighted land on August 28, 1565, the feast day of St. Augustine of Hippo. In honor of the patron saint of his home town of Avilés, he named his colony's settlement San Agustín.[16] The Spanish sailed through the inlet into Matanzas Bay and disembarked near the Timucua town of Seloy on September 6.[17][18][19] Menéndez's immediate goal was to quickly construct fortifications to protect his people and supplies as they were unloaded from the ships, and then to make a proper survey of the area to determine the best place to erect the fort.

The location of this early fort has been confirmed through archaeological excavations directed by Kathleen Deagan on the grounds of what is now the Fountain of Youth Archaeological Park.[17][20] It is known that the Spanish occupied several Native American structures in Seloy village, whose chief, the cacique Seloy, was allied with the Saturiwa, Laudonnière's allies. It is possible, but not yet demonstrated by any archaeological evidence, that Menéndez fortified one of the occupied Timucua structures to use as his first fort at Seloy.[17]

In the meantime, Jean Ribault, Laudonnière's old commander, arrived at Fort Caroline with more settlers for the colony, as well as soldiers and weapons to defend them.[21] He also took over the governorship of the settlement. Despite Laudonnière's wishes, Ribault put most of these soldiers aboard his ships for an assault on St. Augustine. However, he was surprised at sea by a violent storm[22] that lasted several days and wrecked his ships further south on the coast. This gave Menéndez the opportunity to march his forces overland for a surprise dawn attack on the Fort Caroline garrison, which then numbered several hundred people. Laudonnière and some survivors fled to the woods, and the Spanish killed almost everyone in the fort except for the women and children. With the French displaced, Menéndez rechristened the fort "San Mateo", and appropriated it for his own purposes. The Spanish then returned south and eventually encountered the survivors of Ribault's fleet near the inlet at the southern end of Anastasia Island. There Menéndez executed most of the survivors, including Ribault; the inlet has ever since been called Matanzas, the Spanish word for "slaughters".[23]

In 1566, Martín de Argüelles was born in Saint Augustine, the first birth of a child of European ancestry recorded in what is now the continental United States,[24] This was 21 years before the English settlement at Roanoke Island in Virginia Colony, and 42 years before the successful settlements of Santa Fe, New Mexico, and Jamestown, Virginia. In 1606, the first recorded birth of a black child in the continental United States was listed in the Cathedral Parish archives, thirteen years before enslaved Africans were first brought to the English colony at Jamestown in 1619.[25][26] In territory under the jurisdiction of the United States, only Puerto Rico has continuously occupied European-established settlements older than St. Augustine.[27]

Spanish period[edit]

St. Augustine was intended to be a base for further colonial expansion[28] across what is now the southeastern United States, but such efforts were hampered by apathy and hostility on the part of the Native Americans towards becoming Spanish subjects. The Saturiwa, one of the two principal chiefdoms in the area, remained openly hostile.[29] In 1566, the Saturiwa burned St. Augustine and the settlement was relocated. Traditionally it was thought to have been moved to its present location, though some documentary evidence suggests it was first moved to a location on Anastasia Island. At any rate, it was certainly in its present location by the end of the 16th century.[30]

The settlement also faced attacks from European forces. In April 1568 the French soldier Dominique de Gourgue led an attack on Spanish holdings. With the aid of the Saturiwa, Tacatacuru,[31] and other Timucua peoples who had been friendly with Laudonnière, de Gourgues attacked and burned Fort San Mateo, the former Fort Caroline. He executed his prisoners in revenge for the 1565 massacre,[32] but did not approach St. Augustine. Additional French expeditions were primarily raids and could not dislodge the Spanish from St. Augustine.[33] On June 6, 1586, English privateer Sir Francis Drake raided St. Augustine, burning it and driving surviving Spanish settlers into the wilderness. However, lacking sufficient forces or authority to establish an English settlement, Drake left the area, instead heading north to establish contact with the English colony at Roanoke.[34]

In 1668, English privateer Robert Searle attacked and plundered St. Augustine.[35][36] In the aftermath of his raid, the Spanish began in 1672 to construct a more secure fortification, the Castillo de San Marcos.[37] It stands today as the oldest fort in the United States. Its construction took a quarter of a century, with many later additions and modifications.[38]

The Spanish did not import many slaves to Florida for labor,[39] since it was primarily a military outpost without a plantation economy like that of the British colonies. As the British planted settlements south along the Atlantic coast, the Spanish encouraged British slaves to escape to sanctuary in Florida. If the fugitives converted to Catholicism and swore allegiance to the king of Spain, they would be given freedom, arms, and supplies. Over time, St. Augustine would become a major destination for runaway slaves.[40]

By 1683, a militia unit of free black people was formed for the defense of St. Augustine. Many of those in the unit could trace their lineage for several generations back to Spain. The militia unit served as a means for St. Augustine citizens of African descent to increase their standing in society as well as improve race relations with the other Spaniards.[41]

Moving southward on the coast from the northern colonies, the British founded Charleston in 1670 and Savannah in 1733. In response, Spanish Governor Manual de Montiano in 1738 established the first legally recognized free community of ex-slaves, known as Gracia Real de Santa Teresa de Mose, or Fort Mose, to serve as a defensive outpost two miles north of St. Augustine.[42]

In 1740, British forces attacked St. Augustine from their colonies in the Carolinas and Georgia. The largest and most successful of these attacks was organized by Governor and General James Oglethorpe of Georgia;[43] he split the Spanish-Seminole alliance when he gained the help of Ahaya the Cowkeeper,[44] chief of the Alachua band of the Seminole tribe. The Seminole then occupied territory mostly in the north of Florida, but later migrated into the center and south of the peninsula.

In the largest campaign of 1740, Oglethorpe commanded several thousand colonial militia and British regulars, along with Alachua band warriors, and invaded Spanish Florida. He conducted the Siege of St. Augustine as part of the War of Jenkins' Ear (1739–42). During this siege, the black community of St. Augustine was important in resisting the British forces. The leader of Fort Mose during the battle was Capt. Francisco Menendez:[45] born in Africa, he twice escaped from slavery. In Florida, he played an important role in defending St. Augustine from British raids. The Fort Mose site (of which only ruins remain) is now owned and maintained by the Florida Park Service. It has been designated a National Historic Landmark.[46]

British period[edit]

In 1763, the Treaty of Paris ended the Seven Years' War. Spain ceded Florida and St. Augustine to the British, in exchange for the British relinquishing control of occupied Havana.[47] With the change of government, most of the Spanish Floridians and many freedmen departed from St. Augustine for Cuba. Only a few remained to handle unsold property and settle affairs.

James Grant was appointed the first governor of East Florida. He served from 1764 until 1771, when he returned to Britain due to illness. He was replaced as governor by Patrick Tonyn. During this brief period, the British converted the monks' quarters of the former Franciscan monastery into military barracks,[48] which were named St. Francis Barracks. They also built The King's Bakery, which is believed to be the only extant structure in the city built entirely during the British period.

The Lieutenant Governor of East Florida under Governor Grant was John Moultrie, who was born in South Carolina. He had served under Grant as a major in the Cherokee War. During the American War of Independence, he remained loyal to the British Crown, but he had three brothers who served in the Patriot army.[49]

Moultrie was granted large tracts of land in the St. Augustine vicinity, upon which he established a plantation he called "Bella Vista." He owned another 2,000-acre (8.1 km2) plantation in the Tomoka River basin named "Rosetta".[50] While acting as the lieutenant governor, he lived in the Peck House on St. George Street.[51]

During the British period, Andrew Turnbull, a friend of Grant, established the settlement of New Smyrna in 1768. Turnbull recruited indentured servants from the Mediterranean area, primarily the island of Minorca.[52] The conditions at New Smyrna were so abysmal[53] that the settlers rebelled en masse in 1777; they walked the 70 miles (110 km) to St. Augustine, where Governor Tonyn gave them refuge.[54][55] The Minorcans and their descendants stayed on in St. Augustine through the subsequent changes of flags, and marked the community with their language, culture, cuisine and customs.[56]

Second Spanish period[edit]

The Treaty of Paris in 1783 gave the American colonies north of Florida their independence, and ceded Florida to Spain in recognition of Spanish efforts on behalf of the American colonies during the war.

On September 3, 1783, by Treaty of Paris, Britain also signed separate agreements with France and Spain. In the treaty with Spain, the colonies of West Florida, captured by the Spanish, and East Florida were given to Spain, as was the island of Minorca, while the Bahama Islands, Grenada and Montserrat, captured by the French and Spanish, were returned to Britain.[57][58]

Florida was under Spanish control again from 1784 to 1821. There was no new settlement, only small detachments of soldiers, as the fortifications decayed. Spain itself was the scene of war between 1808 and 1814 and had little control over Florida. In 1821 the Adams–Onís Treaty peaceably turned the Spanish provinces in Florida and, with them, St. Augustine, over to the United States. There were only three Spanish soldiers stationed there in 1821.[59]

A relic of this second period of Spanish rule is the Constitution monument, an obelisk in the town plaza honoring the Spanish Constitution of 1812,[60] one of the most liberal of its time. In 1814 King Ferdinand VII of Spain abolished that constitution and had monuments to it torn down; the one in St. Augustine is said to be the only one to survive.[61][62]

American period[edit]

Spain ceded Florida to the United States in the 1819 Adams–Onís Treaty,[63] ratified in 1821; Florida officially became a U.S. possession as the Florida Territory in 1822.[64] Andrew Jackson, a future president, was appointed its military governor and then succeeded by William Pope Duval, who was appointed territorial governor in April 1822.[65] Florida gained statehood in 1845.

After 1821, the United States renamed the Castillo de San Marcos (called Castle St. Marks or Fort St. Mark by the British[66]) "Fort Marion" in honor of Francis Marion,[67] known as the "Swamp Fox" of the American Revolution.

During the Second Seminole War of 1835–42, the fort served as a prison for Seminole captives, including the famed leader Osceola, as well as John Cavallo (John Horse) the black Seminole and Coacoochee (Wildcat), who made a daring escape from the fort with 19 other Seminoles.[68][69] The city produced at least two militia units who fought during the war including one called the St. Augustine Guards. A contemporary observer said that the units were poorly equipped and a "melancholy sight." However, another witness said of the St. Augustine Guards specifically that they were "the generous and spirited young men of St. Augustine."[70]

In 1861, the American Civil War began; Florida seceded from the Union and joined the Confederacy. On January 7, 1861, prior to Florida's formal secession, a local militia unit, the St. Augustine Blues, took possession of St. Augustine's military facilities, including Fort Marion[71] and the St. Francis Barracks, from the lone Union ordnance sergeant on duty. On March 11, 1862, crew from the USS Wabash reoccupied the city for the United States government without opposition.[71][72][73] The fort was used as a site for recuperating Union soldiers and the Confederates never attempted to retake the city. However, Confederate cavalry did attack Union woodcutting parties who traveled too far from the city to gather fuel.[74] In 1865, Florida rejoined the United States.

After the war, freedmen in St. Augustine established the community of Lincolnville in 1866, named after President Abraham Lincoln. Lincolnville, which had preserved the largest concentration of Victorian Era homes in St. Augustine, became a key setting for the Civil Rights Movement in St. Augustine a century later.[75]

After the Civil War, Fort Marion was used twice, in the 1870s and then again in the 1880s, to confine first Plains Indians, and then Apaches, who were captured by the US Army[76] in the West.[77] The daughter of Geronimo was born at Fort Marion,[78][79] and was named Marion. She later changed her name. The fort was also used as a military prison during the Spanish–American War of 1898.[80] It was removed from the Army's active duty rolls in 1900[81] after 205 years of service under five different flags. Having been run temporarily by the St. Augustine Historical Society and Institute of Science in the 1910s, the National Park Service became its custodian and conservator in 1933. In 1942, Fort Marion reverted to its original name of Castillo de San Marcos. It is now run by the National Park Service, and is preserved as the Castillo de San Marcos National Monument, a National Historic Landmark.[82]

Flagler era[edit]

Henry Flagler, a partner with John D. Rockefeller in Standard Oil, arrived in St. Augustine in the 1880s. He was the driving force behind turning the city into a winter resort for the wealthy northern elite.[83] Flagler bought a number of local railroads and incorporated them into the Florida East Coast Railway, which built its headquarters in St. Augustine.[84]

Flagler commissioned the New York architectural firm of Carrère and Hastings to design a number of extravagant buildings in St. Augustine, among them the Ponce de León Hotel and the Alcazar Hotel.[85] He built the latter partly on land purchased from his friend and associate Andrew Anderson and partly on the bed of Maria Sanchez Creek,[86] which Flagler had filled with the archaeological remains of the original Fort Mose.[87][88] Flagler, a Scottish Presbyterian, built or contributed to the construction of several churches of various denominations, including Grace Methodist, Ancient City Baptist, and the ornate Memorial Presbyterian Church of Venetian architectural style, where he was buried after his death in 1912.[89]

Flagler commissioned Albert Spalding to design a baseball park in St. Augustine,[90] and in the 1880s, the waiters at his hotels, under the leadership of headwaiter Frank P. Thompson,[91][92] formed one of America's pioneer professional Negro league baseball teams, the Ponce de Leon Giants.[93] Members of the New York African-American professional team, the Cuban Giants, wintered in St. Augustine, where they played for the Ponce de Leon Giants.[90][94] These included Frank Grant, who in 2006 was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame.[95]

In the 1880s, no public hospital was operated between Daytona Beach and Jacksonville. On May 22, 1888, Flagler invited the most influential women of St. Augustine to a meeting where he offered them a hospital if the community would commit to operate and maintain the facility. The Alicia Hospital opened March 1, 1890, as a not-for-profit institution; it was renamed Flagler Hospital in his honor in 1905.[96][97]

The St. Augustine Alligator Farm, founded in 1893,[98][99] is one of the oldest commercial tourist attractions in Florida, as is the Fountain of Youth Archaeological Park, which has been a tourist attraction since around 1902.[100] The city is the eastern terminus of the Old Spanish Trail, a promotional effort of the 1920s linking St. Augustine to San Diego, California, with 3,000 miles (4,800 km) of roadways.[101][102]

From 1918 to 1968, St. Augustine was the home of the Florida Normal and Industrial Institute, serving African American students. In 1942 it changed its name to Florida Normal and Industrial Memorial College.[103]

The Florida land boom of the 1920s left its mark on St. Augustine with the residential development (though not completion) of Davis Shores, a landfill project of the developer D.P. Davis on the marshy north end of Anastasia Island.[104] It was promoted as "America's Foremost Watering Place", and could be reached from downtown St. Augustine by the Bridge of Lions, billed as "The Most Beautiful Bridge in Dixie".[105]

During World War II, St. Augustine hotels were used as sites for training Coast Guardsmen,[106] including the artist Jacob Lawrence[107] and actor Buddy Ebsen.[108] It was a popular place for R&R for soldiers from nearby Camp Blanding, including Andy Rooney[109] and Sloan Wilson. Wilson later wrote the novel The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit, which became a classic of the 1950s.[110]

Civil rights movement[edit]

St. Augustine was among the pivotal sites of the civil rights movement in 1963–64.[111][112]

Nearly a decade after the Supreme Court ruling in Brown v. Board of Education that segregation of schools was unconstitutional, African Americans were still trying to get the city to integrate the public schools. They were also trying to integrate public accommodations, such as lunch counters,[113] and were met with arrests[114] and Ku Klux Klan violence.[115][116] The police arrested non-violent protesters for participating in peaceful picket lines, sit-ins, and marches. Homes of blacks were firebombed,[117] black leaders were assaulted and threatened with death, and others were fired from their jobs.

In the spring of 1964, St. Augustine based Robert Hayling, president of the Florida Branch of Martin Luther King Jr.'s Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC),[118] asked King for assistance.[119] From May until July 1964, they carried out marches, sit-ins, and other forms of peaceful protest in St. Augustine. Hundreds of black and white civil rights supporters were arrested,[111] and the jails were filled to overflowing.[120] At the request of Hayling and King, white civil rights supporters from the North, including students, clergy, and well-known public figures, came to St. Augustine and were arrested together with Southern activists.[121][122]

The Ku Klux Klan responded with violent attacks that were widely reported in national and international media.[123] Popular revulsion against the Klan violence in St. Augustine generated national sympathy for the black protesters and became a key factor in Congressional passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,[124] leading eventually to passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965,[125] both of which were to provide federal enforcement of constitutional rights.[126]

The black Florida Normal Industrial and Memorial College, whose students had participated in the protests, felt itself unwelcome in St. Augustine, and in 1968 moved to a new campus in Dade County. Today it is Florida Memorial University.

In 2010, at the invitation of Flagler College, Andrew Young premiered his movie, Crossing in St. Augustine,[127] about the 1963–64 struggles against Jim Crow segregation in the city. Young had marched in St. Augustine, where he was physically assaulted by hooded members of the Ku Klux Klan in 1964,[128] and later served as US ambassador to the United Nations.[129]

The city has a privately funded Freedom Trail of historic sites of the civil rights movement,[130] and a museum at the Fort Mose site, the location of the 1738 free black community.[131][132] Historic Excelsior School, built in 1925 as the first public high school for blacks in St. Augustine,[133] has been adapted as the city's first museum of African-American history. In 2011, the St. Augustine Foot Soldiers Monument, a commemoration of participants in the civil rights movement, was dedicated in the downtown plaza a few feet from the former Slave Market.[134] Robert Hayling, the leader of the St. Augustine movement,[135] and Hank Thomas, who grew up in St. Augustine and was one of the original Freedom Riders, spoke at the dedication ceremony.[136] Another corner of the plaza was designated "Andrew Young Crossing" in honor of the civil rights leader,[137] who received his first beating in the movement in St. Augustine in 1964.[138][139][140] Bronze replicas of Young's footsteps have been incorporated into the sidewalk that runs diagonally through the plaza, along with quotes expressing the importance of St. Augustine to the civil rights movement. That project was publicly funded. Some important landmarks of the civil rights movement, including the Monson Motel and the Ponce de Leon Motor Lodge,[141] had been demolished in 2003 and 2004.[142]

Modern era[edit]

Today the city of St. Augustine is a popular travel destination for those in the United States, Canada, and Europe. The city is a well-preserved example of Spanish-style buildings and 18th- and 19th-century architecture. St. Augustine is a very walkable city, with several oceanfront parks. The mild subtropical climate allows for a 12-month tourist season, and many tours operators are based in St. Augustine, offering walking and trolley tours.[143][144]

Architecture and points of interest[edit]

The city's historic center is anchored by St. George Street, which is lined with historic houses from various periods. Some of these houses are reconstructions of buildings or parts of buildings that had been burned or demolished over the years; however, several of them are original structures that have been restored. The city has many well-cared-for and preserved examples of Spanish-style, Mediterranean Revival, British Colonial, and early American homes and buildings.[143][145] From 1959 to 1997, state agency Historic St. Augustine Preservation Board led the restoration and reconstruction efforts of St. Augustine's historic district and operated a living history museum called San Agustín Antiguo, parts of which remain today within the Colonial Quarter Museum.

The Castillo de San Marcos, located on South Castillo Drive, is the oldest masonry fort in the continental United States. Made of a limestone called coquina (Spanish for "small shells"), construction began in 1672. In The fort was declared a National Monument in 1924, and after 251 years of continuous military possession, was deactivated in 1933. The 20.48-acre (8.29 ha) site was then turned over to the United States National Park Service. Today the nearly 350-year-old fort is a popular photo spot for travelers and history buffs.

One of St. Augustine's most notable buildings is the former Ponce de Leon Hotel, now part of Flagler College. Built by millionaire developer and Standard Oil co-founder Henry M. Flagler and completed in 1888, the exclusive hotel was designed in the Spanish Renaissance style for vacationing northerners in winter who traveled south on the Florida East Coast Railway in the late 1800s.

The city also has one of the oldest alligator farms in the United States, opened on May 20, 1893. Today the St. Augustine Alligator Farm Zoological Park is at the center of alligator and crocodile education and environmental awareness in the United States. As of 2012, this was the only place where one can see every species of alligator, crocodile, caiman, and gharial in the United States.

Five statues depicting persons of historical significance to St. Augustine and located out of doors, are connected and featured on a system of signage that makes them accessible to the blind and the sighted called the TOUCH (Tactile Orientation for Understanding Creativity and History) St. Augustine Braille Trail. The statues are of Pedro Menéndez, the founder of St, Augustine; Juan Ponce de León, the first European known to explore the Florida peninsula; the St. Augustine Foot Soldiers, who made civil rights history in the city during the early 1960s; Henry Flagler, who built the Ponce de Leon Hotel, now Flagler College; and Father Pedro Camps and the Menorcans next to the Cathedral Basilica.[146] The system includes an audio tour that may be accessed via phones without internet access as well as desktop computers and smart mobile devices.[147]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ McGrath, John T. (2000). The French in Early Florida: In the Eye of the Hurricane. University Press of Florida. p. 207. ISBN 978-0-8130-1784-6.

- ^ Lyon, Eugene (May 1983). The Enterprise of Florida: Pedro Menéndez de Avilés and the Spanish Conquest of 1565-1568. University Press of Florida. pp. 52–53. ISBN 978-0-8130-0777-9.

- ^ Steigman, Jonathan D. (25 September 2005). La Florida Del Inca and the Struggle for Social Equality in Colonial Spanish America. University of Alabama Press. p. 33. ISBN 978-0-8173-5257-8.

- ^ Lawson, Edward W. (1 June 2008). The Discovery of Florida and Its Discoverer Juan Ponce de Leon (Reprint of 1946 ed.). Kessinger Publishing. pp. 29–32. ISBN 978-1-4367-0883-8.

- ^ Bense, Judith Ann (1999). Archaeology of Colonial Pensacola. University Press of Florida. p. 91. ISBN 978-0-8130-1661-0.

- ^ Europa Publications (2 September 2003). A Political Chronology of the Americas. Routledge. p. 201. ISBN 978-1-135-35652-1.

- ^ Peterson, Harold Leslie (1 October 2000). Arms and Armor in Colonial America, 1526–1783. Courier Corporation. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-486-41244-3.

- ^ Conlin, Joseph (21 January 2009). The American Past: A Survey of American History. Cengage Learning. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-495-57287-9.

- ^ Pickett, Margaret F.; Pickett, Dwayne W. (8 February 2011). The European Struggle to Settle North America: Colonizing Attempts by England, France and Spain, 1521–1608. McFarland. p. 69. ISBN 978-0-7864-6221-6.

...Laudonnière decided to call it the River of Dolphins (today known as the Matanzas River, near St. Augustine).

- ^ Hudson (1 December 2007). Four Centuries of Southern Indians. University of Georgia Press. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-8203-3132-4.

- ^ Bagola, Beatrice (2009). Français du Canada – Français de France VIII (in French). Walter de Gruyter. p. 200. ISBN 978-3-11-023103-8.

- ^ Milanich, Jerald T. (14 August 1996). Timucua. VNR AG. p. 88. ISBN 978-1-55786-488-8.

- ^ McIlwraith, Thomas F.; Muller, Edward K. (1 January 2001). North America: The Historical Geography of a Changing Continent. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 43. ISBN 978-0-7425-0019-8.

- ^ Chartrand, Rene (2006). The Spanish Main 1492–1800. Osprey Publishing. p. 24. ISBN 978-1-84603-005-5.

- ^ Edgar, Walter B. (1998). South Carolina: A History. Univ of South Carolina Press. p. 28. ISBN 978-1-57003-255-4.

- ^ Ring, Trudy; Watson, Noelle; Schellinger, Paul (5 November 2013). The Americas: International Dictionary of Historic Places. Routledge. p. 560. ISBN 978-1-134-25930-4.

- ^ a b c "Menendez Fort and Camp". Historical Archaeology. Florida Museum of Natural History. pp. 1–2. Retrieved May 29, 2011.

- ^ Reps, John William (1965). The Making of Urban America: A History of City Planning in the United States. Princeton University Press. p. 33. ISBN 0-691-00618-0.

- ^ Manucy, Albert C. (1 April 1992). 'Menéndez: Pedro Menéndez de Avilés, Captain General of the Ocean Sea. Pineapple Press. p. 33. ISBN 978-1-56164-015-7.

- ^ Cordell, Linda S.; Lightfoot, Kent; McManamon, Francis; Milner, George (30 December 2008). Archaeology in America: An Encyclopedia: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 349. ISBN 978-0-313-02189-3.

- ^ McGrath, John T. (2000). The French in Early Florida: In the Eye of the Hurricane. University Press of Florida. p. 110. ISBN 978-0-8130-1784-6.

- ^ Hart, Jonathan (26 February 2008). Empires and Colonies. Polity. p. 74. ISBN 978-0-7456-2613-0.

- ^ Weber, David J. (17 March 2009). Spanish Frontier in North America. Yale University Press. p. 49. ISBN 978-0-300-15621-8.

- ^ Barkan, Elliott Robert (17 January 2013). Immigrants in American History: Arrival, Adaptation, and Integration. ABC-CLIO. p. 231. ISBN 978-1-59884-220-3.

- ^ Savage, Beth L.; National Register of Historic Places (1 October 1994). African American Historic Places. John Wiley & Sons. p. 165. ISBN 978-0-471-14345-1.

- ^ Kinshasa, Kwando Mbiassi (1 January 2006). African American Chronology: Chronologies of the American Mosaic. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-313-33797-0.

- ^ RingWatson 2013, p. 619

- ^ David Lee Russell (1 January 2006). Oglethorpe and Colonial Georgia: A History, 1733–1783. McFarland. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-7864-2233-3.

- ^ What Happened?: The nineteenth century. ABC-CLIO. 2011. p. 88. ISBN 978-1-59884-621-8.

- ^ Hann, John H. (1996). A History of the Timucua Indians and Missions. University Press of Florida. pp. 55–57. ISBN 0-8130-1424-7.

- ^ Bushnell, Amy Turner (1995). Situado and Sabana: Spain's Support System for the Presidio and Mission Provinces of Florida. University of Georgia Press. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-8203-1712-0.

- ^ Tucker, Spencer C. (22 January 2014). Battles That Changed American History: 100 of the Greatest Victories and Defeats. ABC-CLIO. p. 6. ISBN 978-1-4408-2862-1.

- ^ Rowland, Lawrence Sanders; Moore, Alexander; Rogers, George C. (1996). The History of Beaufort County, South Carolina: 1514–1861. Univ of South Carolina Press. p. 43. ISBN 978-1-57003-090-1.

- ^ Sir Francis Drake (1981). Sir Francis Drake's West Indian Voyage, 1585–86. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. pp. 39–40. ISBN 978-0-904180-01-5.

- ^ Reich, Paul D.; Leib, Andrew (16 October 2014). Florida Studies: Selected Papers from the 2012 and 2013 Annual Meetings of the Florida College English Association. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 61. ISBN 978-1-4438-6921-8.

- ^ Latimer, Jon (1 June 2009). Buccaneers Of the Caribbean. Harvard University Press. p. 198. ISBN 978-0-674-03403-7.

- ^ Spanish Colonial Fortifications in North America 1565–1822. Osprey Publishing. 2010. p. 6. ISBN 978-1-84603-507-4.

- ^ Fontana, Bernard L. (1994). Entrada: The Legacy of Spain and Mexico in the United States. Southwest Parks and Monuments Association. p. 74. ISBN 978-0-8263-1544-1.

- ^ Jewett, Clayton E.; Allen, John O. (2004). Slavery in the South: A State-by-state History. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 68. ISBN 978-0-313-32019-4.

- ^ Bateman, Rebecca B. (Spring 2002). "Naming Patterns in Black Seminole Ethnogenesis". Ethnohistory. 49 (2): 229.

- ^ Rivers, Larry E. (2000). Slavery in Florida: Territorial Days to Emancipation. Gainesville: University Press of Florida. p. 3. ISBN 9780813018133.

- ^ Mulroy, Kevin (2007). The Seminole Freedmen: A History. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-8061-3865-7.

- ^ Carlisle, Rodney P.; J. Geoffrey Golson (1 January 2006). Colonial America from Settlement to the Revolution. ABC-CLIO. p. 210. ISBN 978-1-85109-827-9.

- ^ Calloway, Colin G. (28 April 1995). The American Revolution in Indian Country: Crisis and Diversity in Native American Communities. Cambridge University Press. p. 221. ISBN 978-1-316-18425-7.

- ^ Sheffer, Debra J. (31 March 2015). Buffalo Soldiers, The: Their Epic Story and Major Campaigns. ABC-CLIO. p. 55. ISBN 978-1-4408-2983-3.

- ^ Charles E. Orser Jnr (11 September 2002). Encyclopedia of Historical Archaeology. Routledge. p. 226. ISBN 978-1-134-60862-1.

- ^ A History of England Part III, 1714–1945. Cambridge University Press Archive. p. 516. GGKEY:DW5NPESTJLG.

- ^ John Gilmary Shea (1888). History of the Catholic Church in the United States ... J. G. Shea. p. 90.

- ^ Barefoot, Daniel W. (1999). Touring South Carolina's Revolutionary War Sites. John F. Blair, Publisher. p. 58. ISBN 978-0-89587-182-4.

- ^ Wayne, Lucy B. (1 July 2010). Sweet Cane: The Architecture of the Sugar Works of East Florida. University of Alabama Press. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-8173-5592-0.

- ^ Atwood, Mary; Weeks, William; Wood, Wayne W. (4 November 2014). Historic Homes of Florida's First Coast. The History Press. p. 97. ISBN 978-1-62619-726-8.

- ^ Landers, Jane G. (2000). Colonial Plantations and Economy in Florida. University Press of Florida. pp. 41–42. ISBN 978-0-8130-1772-3.

- ^ Romans, Bernard (1776). A Concise Natural History of East and West-Florida. Pelican Publishing. p. 270.

- ^ Raab, James W. (5 November 2007). Spain, Britain and the American Revolution in Florida, 1763–1783. McFarland. p. 54. ISBN 978-0-7864-3213-4.

- ^ Kenneth Henry Beeson (2006). Fromajadas and Indigo: The Minorcan Colony in oFlorida. The History Press. p. 19. ISBN 978-1-59629-113-3.

- ^ Ray, Celeste; Charles Reagan Wilson (28 May 2007). The New Encyclopedia of Southern Culture: Volume 6: Ethnicity. University of North Carolina Press. pp. 231–232. ISBN 978-1-4696-1658-2.

- ^ William M. Fowler Jr. (4 October 2011). American Crisis: George Washington and the Dangerous Two Years After Yorktown, 1781–1783. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 119. ISBN 978-0-8027-7809-3.

- ^ Geoffrey S Holmes; Szechi, Daniel (16 July 2014). The Age of Oligarchy: Pre-Industrial Britain 1722–1783. Taylor & Francis. p. 491. ISBN 978-1-317-89425-4.

- ^ Alejandro de Quesada (2010). Spanish Colonial Fortifications in North America 1565–1822. Osprey Publishing. pp. 14–16. ISBN 9781846035074.

- ^ Handbook of Hispanic Cultures in the United States: Sociology. Arte Público Press. 1994. p. 207. ISBN 978-1-55885-074-3.

- ^ George Rainsford Fairbanks (1881). History and Antiquities of St. Augustine, Florida. Horace Drew. p. 102.

- ^ United States. Congress (1906). Congressional edition. U.S. G.P.O. pp. 343–344.

- ^ Lawson, Gary; Seidman, Guy (1 October 2008). The Constitution of Empire: Territorial Expansion and American Legal History. Yale University Press. p. 90. ISBN 978-0-300-12896-3.

- ^ Stathis, Stephen W. (1 April 2003). Landmark Legislation. SAGE Publications. p. 45. ISBN 978-1-4522-6744-9.

- ^ Florida State Bar Association (1922). Proceedings of the ... Annual Session of the Florida State Bar Association ... The Association. p. 81.

- ^ Manucy, Albert; Johnson, Alberta (July 1942). "Castle St. Mark and the Patriots of the Revolution". The Florida Historical Quarterly. 21 (1). Florida Historical Society: 4.

- ^ Tucker, Spencer C. (31 March 2015). American Civil War: A State-by-State Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 133. ISBN 978-1-59884-529-7.

- ^ Reilly, Edward J. (25 June 2011). Legends of American Indian Resistance. ABC-CLIO. p. 104. ISBN 978-0-313-35209-6.

- ^ Hatch, Thom (17 July 2012). Osceola and the Great Seminole War: A Struggle for Justice and Freedom. St. Martin's Press. p. 223. ISBN 978-0-312-35591-3.

- ^ Bittle, George C. (July 1967). "First Campaign of the Second Seminole War". The Florida Historical Quarterly. 46 (1): 41–43. Retrieved 10 March 2023.

- ^ a b Wertz, Jay; Bearss, Edwin C. (4 June 1997). Smithsonian's great battles and battlefields of the Civil War. William Morrow & Co. ISBN 978-0-688-13549-2.

The St. Augustine Blues, a Florida militia unit, seized the fort from a U.S. Army ordnance sergeant on January 7, 1861.

- ^ Barney, William L. (5 July 2011). The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Civil War. Oxford University Press. p. 109. ISBN 978-0-19-987814-7.

- ^ Redd, Robert (11 February 2014). St. Augustine and the Civil War. The History Press. pp. 24–26. ISBN 978-1-62584-657-0.

- ^ Taylor, Paul (2001). Discovering the Civil War in Florida : a reader and guide (1st ed.). Sarasota, Fla.: Pineapple Press. pp. 127–128. ISBN 1561642347.

- ^ James Oliver Horton (24 March 2005). Landmarks of African American History. Oxford University Press. p. 118. ISBN 978-0-19-514118-4.

- ^ Welsh, Herbert (1887). The Apache Prisoners in Fort Marion, St. Augustine, Florida. Office of the Indian rights association. p. 39.

- ^ Worcester, Donald E. (8 April 2013). The Apaches: Eagles of the Southwest. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 306. ISBN 978-0-8061-8734-1.

- ^ H. Henrietta Stockel (1 September 2006). Shame and Endurance: The Untold Story of the Chiricahua Apache Prisoners of War. University of Arizona Press. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-8165-2614-7.

- ^ Congressional Serial Set. U.S. Government Printing Office. 1887. p. 52.

- ^ United States. Office of Archeology and Historic Preservation; Arana, Luis R. (1967). Castillo de San Marcos National Monument ... and Fort Matanzas National Monument ...: historical research management plan. p. 20.

- ^ Beth Rogero Bowen (2008). St. Augustine in the Gilded Age. Arcadia Publishing. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-7385-5342-9.

- ^ Irons-Georges, Tracy; Editors of Salem Press (2001). America's Historic Sites: Alabama-Indiana, 1-456. Salem Press. p. 330. ISBN 9780893561239.

{{cite book}}:|author2=has generic name (help) - ^ Sandra Wallus Sammons (2010). Henry Flagler, Builder of Florida. Pineapple Press Inc. p. 16. ISBN 978-1-56164-467-4.

- ^ Beth Rogero Bowen; The St. Augustine Historical Society (March 2012). St. Augustine in the Roaring Twenties. Arcadia Publishing. p. 44. ISBN 978-0-7385-9121-6.

- ^ Sennott, Stephen (1 January 2004). Encyclopedia of Twentieth Century Architecture. Taylor & Francis. p. 217. ISBN 978-1-57958-433-7.

- ^ Graham, Thomas (2004). Flagler's St. Augustine Hotels: The Ponce de Leon, the Alcazar, and the Casa Monica. Pineapple Press Inc. p. 19. ISBN 978-1-56164-300-4.

- ^ Nolan, David (1995). The Houses of St. Augustine. Pineapple Press Inc. p. 48. ISBN 978-1-56164-069-0.

- ^ "Fort Mosé Historic State Park Unit Management Plan" (PDF). Florida Department of Environmental Protection Division of Recreation and Parks. June 2, 2005. p. 7. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 3, 2011.

- ^ Buker, George E.; Jean Parker Waterbury; St. Augustine Historical Society (June 1983). The Oldest city: St. Augustine, Saga of Survival. St. Augustine Historical Society. p. 196. ISBN 978-0-9612744-0-5.

- ^ a b McNeil, William (2007). Black Baseball Out of Season: Pay for Play Outside of the Negro Leagues. McFarland. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-7864-2901-1.

- ^ Graham 2004, p. 64

- ^ Bruns, Roger A. (2012). Negro Leagues Baseball. ABC-CLIO. pp. 7–8. ISBN 978-0-313-38648-0.

- ^ Harvey, Karen D.; Harvey, Karen G. (1992). America's First City: St. Augustine's Historic Neighborhoods. Tailored Tours Publications. p. 109. ISBN 978-0-9631241-2-8.

- ^ James Weldon Johnson; Sondra Kathryn Wilson (1933). Along this Way: The Autobiography of James Weldon Johnson. Da Capo Press. p. 36. ISBN 978-0-306-80929-3.

- ^ Cassuto, Leonard; Partridge, Stephen (21 February 2011). The Cambridge Companion to Baseball. Cambridge University Press. p. 64. ISBN 978-1-139-82620-4.

- ^ Sidney Walter Martin (1 February 2010). Florida's Flagler. University of Georgia Press. p. 129. ISBN 978-0-8203-3488-2.

- ^ Adams, William R.: St. Augustine and St. Johns County: A Historical Guide ISBN 1-56164-432-3, page 60

- ^ Proceedings of the 26th, 27th, 28th, and 29th International Herpetological Symposia on Captive Propagation & Husbandry: 2002, 2003, 2004 and 2005. International Herpetological Symposium, Incorporated. 2006. p. 19.

- ^ Brantz, Dorothee (8 July 2010). Beastly Natures: Animals, Humans, and the Study of History. University of Virginia Press. p. 135. ISBN 978-0-8139-2947-7.

- ^ Reynolds, Charles B. (1937). "Fact Versus Fiction for the New Historical St. Augustine". University of Florida Digital Collections. Mountain Lakes, New Jersey: Charles B. Reynolds. p. 29. Archived from the original on April 20, 2015.

- ^ Spanish California and the Gold Rush. Automobile Club of Southern California. 1920. p. 175.

- ^ Wadzeck, Caroline (11 March 2014). The Streets of Dayton, Texas: History by the Block. The History Press. p. 138. ISBN 978-1-62619-473-1.

- ^ Tameka Bradley Hobb. "Florida Memorial University: Our History". Fmuniv.edu. Miami Gardens, Florida. Archived from the original on September 11, 2014. Retrieved 6 May 2016.

- ^ Wynne, Nick; Moorhead, Richard (2010). Paradise for Sale: Florida's Booms and Busts. The History Press. p. 89. ISBN 978-1-59629-844-6. Retrieved 11 August 2013.

- ^ Nolan, David (1984). Fifty Feet in Paradise: The Booming of Florida. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. p. 196. ISBN 978-0-15-130748-7.

- ^ "Florida in World War II – The War Comes to St. Augustine" (PDF). nps.gov. Department of the Interior. p. 1.

...until August of 1942 when the U. S. Coast Guard took over several local hotels, the direct impact of war on St. Augustine had been limited. The Ponce de Leon Hotel (now Flagler College) was converted into a Coast Guard boot camp, where young men learned the art of war. At any given time, as many 2,500 guardsmen were stationed in St. Augustine.

- ^ "Jacob A. Lawrence (1917–2000)". uscg.mil. Department of Homeland Security.

- ^ Wise, James E.; Anne Collier Rehill (1 September 2007). Stars in Blue: Movie Actors in America's Sea Services. Naval Institute Press. p. 163. ISBN 978-1-59114-944-6.

- ^ Rooney, Andrew A. (October 2010). Andy Rooney: 60 Years of Wisdom and Wit. PublicAffairs. p. ix. ISBN 978-1-58648-903-8.

- ^ Wilson, Sloan (April 1976). What Shall We Wear to This Party?: The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit Twenty Years Before & After. Arbor House. pp. 133–134. ISBN 978-0-87795-119-3.

- ^ a b Singleton, Dorothy M. (18 March 2014). Unsung Heroes of the Civil Rights Movement and Thereafter: Profiles of Lessons Learned. UPA. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-7618-6319-9.

- ^ "St. Augustine Movement 1963–1964". Civil Rights Movement Archive. 2004. Retrieved March 4, 2011.

- ^ Charles S. Bullock III; Rozell, Mark J. (15 March 2012). The Oxford Handbook of Southern Politics. Oxford University Press. p. 160. ISBN 978-0-19-538194-8.

- ^ The Crisis Publishing Company, Inc. (1963). The Crisis. The Crisis Publishing Company, Inc. p. 412. ISSN 0011-1422.

- ^ Ramdin, Ron (2004). Martin Luther King, Jr. Haus Publishing. p. 88. ISBN 978-1-904341-82-6.

- ^ Jackson, Thomas F. (17 July 2013). From Civil Rights to Human Rights: Martin Luther King, Jr., and the Struggle for Economic Justice. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 190. ISBN 978-0-8122-0000-3.

- ^ "FBI Report of 1964-02-08". OCLC. Federal Bureau of Investigation. p. 3. Archived from the original on July 6, 2008.

(redacted) St. Augustine, Florida, advised that what appeared to be a Molotov cocktail was thrown at the back of his house at the above address causing a serious fire.

- ^ Kirk, John (6 June 2014). Martin Luther King Jr. Routledge. pp. 103–104. ISBN 978-1-317-87650-2.

- ^ Webb, Clive (15 August 2011). Rabble Rousers: The American Far Right in the Civil Rights Era. University of Georgia Press. p. 169. ISBN 978-0-8203-4229-0.

- ^ Goodwyn, Larry (January 1965). "Anarchy in St. Augustine". Harpers.org. Harper’s Magazine. Archived from the original on April 21, 2015.

Sheriff Davis was beginning to use harsh treatment against demonstrators who were in jail. He would herd both men and women into a barbed-wire pen in the yard in a 99-degree sun; he kept them there all day. Water was insufficient and there was no latrine. At night the prisoners were crowded in small cells without room to lie down.

- ^ Vorspan, Albert; Saperstein, David (1998). Jewish Dimensions of Social Justice: Tough Moral Choices of Our Time. UAHC Press. pp. 204–205. ISBN 978-0-8074-0650-2.

- ^ Haynes, Stephen (8 November 2012). The Last Segregated Hour: The Memphis Kneel-Ins and the Campaign for Southern Church Desegregation. Oxford University Press. p. 44. ISBN 978-0-19-539505-1.

- ^ Curtis, Nancy C. (1 August 1998). Black Heritage Sites: The South. The New Press. p. 99. ISBN 978-1-56584-433-9.

- ^ Pitre, Merline; Glasrud, Bruce A. (20 March 2013). Southern Black Women in the Modern Civil Rights Movement. Texas A&M University Press. p. 43. ISBN 978-1-60344-999-1.

- ^ Goldfield, David (7 December 2006). Encyclopedia of American Urban History. SAGE Publications. p. 201. ISBN 978-1-4522-6553-7.

- ^ Branch, Taylor (16 April 2007). Pillar of Fire: America in the King Years 1963–65. Simon and Schuster. p. 606. ISBN 978-1-4165-5870-5.

- ^ Nolan, David (February 11, 2015). "The Two Souls of St. Augustine". Folio Weekly. Folio Weekly. Archived from the original on April 22, 2015.

- ^ DeRoche, Andrew J. (1 October 2003). Andrew Young: Civil Rights Ambassador. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-7425-9933-8.

- ^ DeRoche 2003, p. 71

- ^ "African-American History and Heritage on Florida's Historic Coast A Place of History & Heritage for Many Peoples" (PDF). Florida Historic Coast. Florida Historic Coast. 2015. p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 22, 2015.

- ^ Landers, Jane (1 January 1999). Black Society in Spanish Florida. University of Illinois Press. p. 250. ISBN 978-0-252-06753-2.

- ^ Jones, Maxine D.; McCarthy, Kevin M. (1993). African Americans in Florida. Pineapple Press Inc. p. 13. ISBN 978-1-56164-031-7.

- ^ McCarthy, Kevin M. (1 January 2007). African American Sites in Florida. Pineapple Press Inc. p. 243. ISBN 978-1-56164-385-1.

- ^ "The Heroic Stories of the St. Augustine Foot Soldiers Whose Brave Struggle Helped Pass the Civil Right Act of 1964". civilrights.flagler.edu. Civil Rights Library of St. Augustine. May 14, 2011. p. 17. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 22, 2015.

- ^ David Mark Chalmers (1981). Hooded Americanism: The History of the Ku Klux Klan. Duke University Press. p. 378. ISBN 0-8223-0772-3.

- ^ Griffin, Justine (May 15, 2011). "City unveils Foot Soldiers monument Crowd celebrates work of local civil rights crusaders". St. Augustine.com. St. Augustine, Florida: St. Augustine Record. Archived from the original on June 1, 2013.

- ^ Cotton, Dorothy (4 September 2012). If Your Back's Not Bent: The Role of the Citizenship Education Program in the Civil Rights Movement. Simon and Schuster. p. 232. ISBN 978-1-4391-8742-5.

- ^ Wyn Craig Wade (1998). The Fiery Cross: The Ku Klux Klan in America. Oxford University Press. p. 330. ISBN 978-0-19-512357-9.

- ^ Peggy Smeeton Stanton (1 November 1978). The Daniel dilemma: The Moral Man in the Public Arena. Word Books. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-8499-0087-7.

- ^ Eubanks, Gerald (1 October 2012). The Dark Before Dawn. iUniverse. p. 66. ISBN 978-1-4759-5555-2.

- ^ Epps, Henry. A Concise Chronicle History of the African-American People Experience in America. Lulu.com. p. 276. ISBN 978-1-300-16143-1.

- ^ Flagler 2011, p. 6

- ^ a b "Maps and Directions for St. Augustine, Florida". The St. Augustine Record. Retrieved November 10, 2011.

- ^ "St. George Street" (PDF). The St. Augustine Record. Retrieved November 10, 2011.

- ^ "St. George Street" (PDF). The St. Augustine Record. Retrieved November 10, 2011.

- ^ "TOUCH St. Augustine Braille Trail to be unveiled". staugustine.com. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- ^ "TOUCH St. Augustine, Enhancing Public Art Accessibility in the Nation's Oldest City". staaa.org. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

Bibliography[edit]

- Abbad y Lasierra, Iñigo, "Relación del descubrimiento, conquista y población de las provincias y costas de la Florida" – "Relación de La Florida" (1785); edición de Juan José Nieto Callén y José María Sánchez Molledo.

- Colburn, David, Racial Change and Community Crisis: St. Augustine, Florida, 1877–1980 (1985), New York: Columbia University Press.

- Corbett, Theodore G. "Migration to a Spanish imperial frontier in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries: St. Augustine." Hispanic American Historical Review (1974): 414-430 in JSTOR

- Deagan, Kathleen, Fort Mose: Colonial America's Black Fortress of Freedom (1995), Gainesville: University Press of Florida.

- Fairbanks, George R. (George Rainsford), History and antiquities of St. Augustine, Florida (1881), Jacksonville, Florida, H. Drew.

- Gannon, Michael V., The Cross in the Sand: The Early Catholic Church in Florida 1513–1870 (1965), Gainesville: University Presses of Florida.

- Goldstein, Holly Markovitz, "St. Augustine's "Slave Market": A Visual History," Southern Spaces, 28 September 2012.

- Graham, Thomas, The Awakening of St. Augustine, (1978), St. Augustine Historical Society

- Hanna, A. J., A Prince in Their Midst, (1946), Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

- Harvey, Karen, America's First City, (1992), Lake Buena Vista, Florida: Tailored Tours Publications.

- Harvey, Karen, St. Augustine Enters the Twenty-first Century, (2010), Virginia Beach, VA: The Donning Company.

- Landers, Jane, Black Society in Spanish Florida (1999), Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

- Lardner, Ring, Gullible's Travels, (1925), New York: Scribner's.

- Lyon, Eugene, The Enterprise of Florida, (1976), Gainesville: University Press of Florida.

- Manucy, Albert, Menendez, (1983), St. Augustine Historical Society.

- Marley, David F. (2005), "United States: St. Augustine", Historic Cities of the Americas, vol. 2, Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO, p. 627+, ISBN 1-57607-027-1

- McCarthy, Kevin (editor), The Book Lover's Guide to Florida, (1992), Sarasota, Florida: Pineapple Press.

- Nolan, David, Fifty Feet in Paradise: The Booming of Florida, (1984), New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

- Nolan, David, The Houses of St. Augustine, (1995), Sarasota, Florida: Pineapple Press.

- Porter, Kenneth W., The Black Seminoles: History of a Freedom-Seeking People, (1996), Gainesville: University Press of Florida.

- "City and History of St. Augustine", Rand, McNally & Co.'s Handy Guide to the Southeastern States, Chicago: Rand, McNally & Co., 1899 – via Internet Archive

- Reynolds, Charles B. (Charles Bingham), Old Saint Augustine, a story of three centuries, (1893), St. Augustine, Florida E. H. Reynolds.

- Richardson, F.H. (1905). "St. Augustine, Fla.". Richardson's Southern Guide. Chicago: Monarch Book Company – via Internet Archive.

- Torchia, Robert W., Lost Colony: The Artists of St. Augustine, 1930–1950, (2001), St. Augustine: The Lightner Museum.

- Turner, Glennette Tilley, Fort Mose, (2010), New York: Abrams Books.

- United States Commission on Civil Rights, 1965. Law Enforcement: A Report on Equal Protection in the South. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office.

- Warren, Dan R., If It Takes All Summer: Martin Luther King, the KKK, and States' Rights in St. Augustine, 1964, (2008), Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press.

- Waterbury, Jean Parker (editor), The Oldest City, (1983), St. Augustine Historical Society.

External links[edit]

- Twine Collection Images of Lincolnville between 1922 and 1927. From the State Library & Archives of Florida.