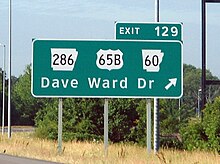

Highway markers for Interstate 40, US Highway 62 and AR 7 | |

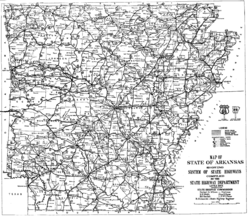

A map of highways in the state of Arkansas | |

| System information | |

|---|---|

| Length | 16,442.90 mi[1] (26,462.28 km) |

| Formed | 1924 |

| Highway names | |

| Interstates | Interstate nn (I-nn) |

| US Highways | US Route n (US nn) |

| State | Highway nn |

| System links | |

The Arkansas Highway System is made up of all the highways designated as Interstates, U.S. Highways and State Highways in the US state of Arkansas. The system is maintained by the Arkansas Department of Transportation (ArDOT), known as the Arkansas State Highway Department (AHD) until 1977 and the Arkansas State Highway and Transportation Department (AHTD) from 1977 to 2017. The system contains 16,442.90 miles (26,462.28 km) of Interstates, U.S. Routes, state highways, and special routes. The shortest members are unsigned state highways Arkansas Highway 806 and Arkansas Highway 885, both 0.09 miles (0.14 km) in length. The longest route is U.S. Route 67, which runs 296.95 miles (477.89 km) from Texarkana to Missouri.

History[edit]

Early beginnings, the "Dollarway"[edit]

Travel in Arkansas has come from very humble beginnings. In the late nineteenth century, travelers would follow dirt paths riddled with potholes, and ruts. Bicycles would frequently stick in mud puddles. Trains never became popular in Arkansas, and instead travelers would use horse and buggy to get around the rural parts of state, and bicycles within cities.[2] Across the nation, many cyclists began demanding better roads to use for travel, and these road enthusiasts formed groups to advance their cause. A group of Arkansas cyclists held a good roads convention in Little Rock just before the turn of the century. Arkansas automobile salesmen quickly picked up on the notion that better roads would help their business as well, and became the driving force behind the Arkansas good roads movement.[3] The enterprising salesmen greatly increased the movement's breadth by expanding their scope outside of city streets to farm to market routes, a move that enticed farmers to support the cause. The combination of money from Little Rock salesmen and the large number of farmers in the state made the good roads movement a formidable alliance.[4] At this time, the roads were maintained by a state law that mandated all healthy men of middle age contribute five days of road work (or a monetary equivalent) annually.

Another convention in 1907 formed road districts, but this did not help the situation either. Although the need for improvement was obvious, the citizens had trouble finding funding for their goals.[5] In December 1913, Arkansas formed the "Dollarway", which was the name of a concrete road with asphalt concrete topping. It was opened near Pine Bluff.[6] By 1914, a segment of 23 miles (37 km) was opened, the longest paved stretch in the United States. Today, the route is mostly covered by Highway 365, although some original concrete segments are still visible, and the Dollarway Road portion has been listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[7]

Arkansas' "district approach" dooms hopes of unity[edit]

Now that Arkansas had discovered a durable paving system, concrete topped with asphalt of "Dollarway pavement", they could replace the often-broken macadam roads. Dollarway was also a more economical choice, as macadam would frequently need replacing. As Arkansans sought improved roads across the state, the General Assembly eschewed centralized planning and financing of transportation corridors, instead passing a law allowing local adjacent property owners to design, construct, and issue bonds for roads within their boundaries. The system led to a fractured series of roadways with inconsistent quality rather than a network, and was often driven by provincial interests, corruption, and fraud.[8][9] In 1913, the Arkansas Highway Commission was ordered with the task of organizing the state's road system. In 1915, the Commission was charged with misappropriating funds for officials to use on automobiles and gasoline, making the financial situation even worse. The Alexander Road law of 1915 allowed those close to a route to form their own districts and subsequently contract out the work themselves. This resulted in wild variations of how the same road was paved from district to district and from county to county.[9]

In 1917, the Arkansas General Assembly enacted Act 105, designating all public roads (except within cities) as state roads eligible to receive federal aid in response to the Federal Aid Road Act of 1916.[10] The Act had a limited scope, small appropriation limits, and implementation was delayed nationwide due to World War I. The Federal Aid Highway Act of 1921, was passed in an effort to remedy the deficiencies of the 1917 legislation. It allowed for funds to be allocated for a state highway system, as long as a central highway authority meeting certain requirements was in charge of disbursing funds, which was not the case in Arkansas at the time. The Arkansas legislature was slow to create an authority capable of meeting the Federal Aid Act's requirements, opting instead to stay with the district approach, which cost the state millions of dollars in funds. During this period, district leaders were caught charging exorbitant taxes for road projects, and especially where districts overlapped, bankrupting farmers.[11] The federal government decided to withhold money from states without a unified highway authority. When the General Assembly again tried to create one, the local county judges (usually profiting from the exorbitant district fees) blocked the legislation. Since Arkansas was not in compliance with the Federal Aid Act of 1921, the state was declared ineligible for federal funds in 1923.

Arkansas creates the State Highway Commission, restores federal funding[edit]

| 1924 designation | meaning |

|---|---|

| A1-A9 | Primary federal aid roads |

| B1-B43 | Secondary federal aid roads |

| C1-C46 | Connecting state roads |

Upon withdrawal of federal money in 1923, Governor Thomas McRae called a special session of the General Assembly to solve the problem. The result was Act 5, commonly known as the Harrelson Road Law. The most significant provision of the law created a state highway system, and the roads within it were eligible for federal funding to be disbursed by the Commission. The Commission gained significant influence over construction by having the ability to disburse federal aid to projects meeting its standards. The law also consolidated all construction and maintenance activities on public roads under the Highway Commission supervision, ensuring roads were built to Commission standards. The law also modified the number of commissioners, how they were appointed, and term limits.

The state highway system was first created on October 10, 1923, by the Commission.[12] The group traced all roads designated as "county roads" onto an official map, which became the official State Highway System of Arkansas on December 31, 1924.[13] This map was kept in Little Rock as the official log of routes.

The U.S. Route system came to Arkansas in 1926, and Arkansas gave its state highways numbers to match the national trend of numbered routes. This numbering remains largely intact today. During this time, many motor inns, such as the Tall Pines Motor Inn in Carroll County, Arkansas, or the Crystal River Tourist Camp became favored by motorists over roadside camping.[14] Arkansans and Americans were quickly becoming an automobile culture, and the open road became more accessible to the public.

The Harrelson Road Law also eased the tax burdens of farmers significantly. Property owners wouldn't be fully relieved of financial responsibility until the Martineau Road Law of 1927, when the State of Arkansas assumed all road debt. After assuming this debt, the state added many taxes to the road users instead of the property owners. The State Road Patrol was established in 1929 to police the roads.[15] The State Highway Commission would redesignate Arkansas highways in 1929, including an additional 1,812 miles (2,916 km). The situation would worsen with the Great Depression, when Arkansas was forced to default on many highway loans. The Federal Defense Highway Act of 1941 ordered construction funds be used only on important defense highways, but Arkansas's poorly maintained roads needed funding statewide.[16]

Reform efforts[edit]

By 1948, the state's highways had deteriorated so far to become a central political issue in the governor's race. Sid McMath, ran on a platform of business progressivism, with highway reform as the cornerstone issue. Taking over as governor after the 1948 election, McMath and the General Assembly passed a bond measure to raise construction and maintenance funds for roads and bridges.[16] A special bond election on February 15, 1949, was voter approved for additional bond funds by an overwhelming margin.[16] The unprecedented highway spending greatly improved and expanded the highway system, but also enabled local potentates to direct funds for political advantage.[a]

An audit commission of the Highway Department found widespread corruption and cronyism in early 1952, slowing McMath's reform efforts. He was ousted that fall and replaced by a more conservative Francis Cherry, who sought reforms within the Highway Department.[18] The same election saw voters approving Constitutional Amendment No. 42 (known as the Mack-Blackwell Amendment) by a large margin, which created an autonomous Arkansas State Highway Commission to manage the Highway Department, reducing the governor's influence.[b]

Several other proposals for highway reform were studied during this period.[18] The Arkansas Senate requested a feasibility study for designating all roads in the state (except those within municipal areas) as state highways in 1955.[12] If feasible, Arkansas would have likely adopted a system similar to Missouri, which maintains a system of supplemental routes in addition to state highways. Arkansas considered the systems of Delaware, North Carolina, Virginia, West Virginia, Tennessee, Missouri, and Mississippi. The first four states listed previously were the only states to have comprehensive state highway plans at the time. Arkansas decided not to begin a comprehensive program, and instead discovered that thousands of miles should no longer even receive county funding due to heavy population losses.[12]

Interstate Highway system comes to Arkansas[edit]

| Year | Miles |

|---|---|

| 1923 | 6,718.55

|

| 1925 | 8,345.50

|

| 1930 | 8,809.50

|

| 1935 | 8,927.41

|

| 1940 | 9,301.20

|

| 1945 | 9,753.08

|

| 1950 | 9,716.13

|

| 1955 | 10,037.69

|

| 1960 | 11,148.85

|

| 1965 | 13,294.72

|

| 1970 | 14,612.37

|

| 1975 | 15,821.32

|

| 1980 | 16,090.88

|

| 1985 | 16,117.47

|

| 1990 | 16,203.04

|

| 1995 | 16,254.61

|

| 2000 | 16,366.77

|

| 2010[21] | 16,416.18

|

| 2015[22] | 16,424.07

|

Chief engineer Alfred Johnson was one of the main proponents of the Interstate System, and construction of interstate highways in Arkansas actually began before the system became official in 1956. The state's original five interstates, Interstate 30, Interstate 40, Interstate 55, Interstate 430, and Interstate 540 still exist in large part today.[23] Arkansas had returned to the forefront of the highway world in 1962 because of the interstate system, just as the Dollarway had made Arkansas a leader decades earlier.[23] 1957 brought the Milum Road Act, which created (at minimum) eleven additional miles of state highways in each of Arkansas' 75 counties.

Today[edit]

Arkansas still suffers from the impact of the districts. Despite the creation of a highway department and numerous attempts to keep politics away from road funding, the system is still flawed. This is due partly to the nature of Arkansas - many citizens prefer to live in many very small communities rather than in small towns (especially in delta region and South Arkansas). This creates more need for connecting highways between these communities. Another cause of inefficiency is the use of Commissioners that represent geographical regions. The regions have not been reapportioned, and this causes the growing Northwest Arkansas region to be treated the same as the shrinking East Arkansas area.[24] Arkansas' highway system was consistently ranked one of America's worst until the AHTD launched a $575 million program in 1999. The project was innovative in its funding as well, raising the diesel fuel tax by four cents and matching federal dollars with state dollars to rehab over 350 miles (560 km) of Interstate highway in 54 separate projects.[25]

The state is in various stages of adding more Interstate highways within its borders. Interstate 555, designated in 2016, serves as a spur to Jonesboro from Interstate 55. Arkansas is also working to bring Interstate 49 along its western edge, eventually connecting Kansas City and New Orleans. This route is being constructed as Arkansas Highway 549 temporarily. The southeast portion of the state is seeing an extension of Interstate 530, which will eventually connect Little Rock to Interstate 69 in Arkansas.

Routes and sections[edit]

Highways in Arkansas do not commonly form concurrencies with other state highways, they instead exist in many officially designated "sections".[1] These sections are not apparent to the traveler except on mile markers. Because roads often stop and begin elsewhere, it appears that highways repeat themselves in multiple locations, the most recurring being Highway 74. All highways follow this convention in ArDOT bookkeeping, including Interstates and U.S. Routes.[1] A route remains a single segment until it meets a route of greater importance, or often a county line. This is the procedure for all highways in Arkansas, unless an officially designated "exception" occurs, which means a concurrency does form. These occur on mile markers and on bridge designation signs, however, mile markers are uncommon in Arkansas, and bridge markers are also frequently missing. Sectioning is used as the rule throughout the state, unless an officially designated "exception" occurs.[1] These exceptions are not common and are the only instances of concurrencies in the State of Arkansas.

State highways in Arkansas are not usually marked with "Begin" or "End" banners, which can compound the problem. The Arkansas State Highway and Transportation Department does provide by-county Route and Section Maps which show the section number and mileage per section.

Signage[edit]

| Shield type | 1 digit | 2 digits | 3 digits |

|---|---|---|---|

| Interstate | none | ||

| U.S. route | |||

| U.S. special route | |||

| State highway (with a "1") | |||

| State highway (standard) | |||

| State highway special routes | |||

| County highway | varies | ||

Two-digit U.S. and Arkansas highways are marked with a 24-by-24-inch (61 cm × 61 cm) black sign with black numbers contained within a white outline of Arkansas, with three-digit shields using a 24-by-36-inch (61 cm × 91 cm) area. One-digit routes use MUTCD Series D, two-digit routes use MUTCD Series C, and three-digit routes use MUTCD Series B font. The exception is if a three-digit shield includes a "1", such as "100" or "314", in which case Series C is used. Arkansas does not have any four-digit highways.

The outline of the state on state highway markers varies across the state based on what agency posts the shields. The Arkansas state outline is more realistic on the one- and two-digit shields, because on three digit shields the state is stretched to fit the third number. Major changes usually involve Arkansas's eastern border along the Mississippi River and the Missouri Bootheel. Although the Bootheel actually cuts into the state forming an acute angle, some shields represent the Bootheel as a square intrusion into the state. The state line is indeterminate along the Mississippi River, and different variants have different levels of accuracy along the eastern border.[26]

For business routes and spurs, Arkansas uses the standard state highway shields with a small "B" for a business routes or a "S" for spur. The letter is raised up in an almost-exponential format. Single-digit special routes are printed on 24-by-24-inch (61 cm × 61 cm) shields, with two- and three-digit routes using the 24-by-36-inch (61 cm × 91 cm) dimensions. Some routes have directional components, and the N, E, S, or W are signed in the same manner. The state of Arkansas has some special shields, including an airplane-themed shield for Arkansas Highway 980, which is the designation for all state-maintained airport access roads. Another special shield is Highway 917, which is funded by marine fuel taxes.

On two-digit, non-freeway U.S. routes, Arkansas uses the 1961 standard U.S. Route shield; the 1971 standard shield is used on freeways, three-digit U.S. routes and special U.S. routes. Special U.S. routes include a "B" for business routes or a "S" denoting a spur route. This is not standard MUTCD practice.

Interstate Highways in Arkansas are signed with the state's name on every shield, with two-digit shields being 36 by 36 inches (91 cm × 91 cm), while three-digit shields are 36-by-42-inch (91 cm × 107 cm), and 24 by 24 inches (61 cm × 61 cm) and 25 by 30 inches (64 cm × 76 cm), respectively, on intersecting roads. In the field, however, signs posted by municipalities sometimes lack the "Arkansas" banner and often use non-standard numbering font. Arkansas does not have any special Interstate routes.

Historic shields[edit]

Arkansas first established a statewide state highway system in 1924. This system labeled its routes in a "letter-number number" system such as A-11. The roads were all designated as "State Road l-nn" prior to the creation of the U.S. Numbered Highway System. Upon creation of the Harrelson Road Law, the US Route system came to Arkansas and the system was renumbered. This system has generally remained in place, with the major addition of the Interstate Highway System in 1965. The original system had just over 100 routes, mostly dirt paths that became unpassable after rain. Arkansas began using the same pavement techniques used for Dollarway Road, which was the longest continuous concrete pavement in the United States when completed in 1913.

These routes were signed with white cut-out shapes of Arkansas, which said "State Road" in addition to the route number. In the 1950s, the Arkansas Highway Department removed the "State Road" and instead printed "ARKANSAS" on top of the shields, with a line underneath the state name. The shields were changed to the current format circa 1971, though all numbers were within square shields. A wider sign was created later to allow three-digit routes to use the same font size as two-digit routes.

Safety[edit]

In 2019, contribution of Arkansas to Transportation safety in the United States makes Arkansas has 210 out of 19,499 fatalities in Urban area and 306 out of 16,410 in rural areas.[27]

Highway systems[edit]

Although routes are sometimes dually signed (I-49 and US 71 in Northwest Arkansas for example) due to Arkansas' use of concurrencies, the actual pavement belongs to either the one highway or the other, not both.

Interstates[edit]

U.S. routes[edit]

State Highways[edit]

Despite being a state of average size, Arkansas has an expansive highway system. This is due to a variety of issues, including a largely rural early geography, a historical tendency to settle in rural settlements rather than incorporated municipalities, topography (especially in the northwestern half of the state), legislation, government and politics.

The highest numbers used for highway designations include Highway 889 in Little Rock, although this route is not signed. The lowest numbers in use are Highway 1 in east Arkansas and Highway 4. Most designations between 1-300 are in use, in some cases several times, with some highways in the 300s. ArDOT only uses 400 numbers as a prefix, such as 463 being a former alignment of US 63. Arkansas uses the 500 number to designate future signings, such as Highway 549 for pieces of a future I-49 extension. No discernible pattern exists in Arkansas's numbering system, although most even numbered highways are signed east-west and odds signed north-south. However, the actual roadways carrying these designations may be switched. Highway 600 is the designation for all state park roads in Arkansas, with designations higher generally being unsigned minor routes connecting state property or facilities to the state highway system.

Scenic Byways[edit]

County highways[edit]

County highway systems in Arkansas use a variety of signs, and vary widely from one county to another. County road systems in Arkansas have a dichotomy between county roads and local roads (or private roads). Although both systems are owned by the county, the "county road" system generally encompasses roads of county significance, or roads that would be used for through travel.[28] The local road system encompasses dead ends or other highways that would generally not be used by the traveling public, except for adjacent property owners. Generally, local roads are not subject to improvement projects by county highway departments.

No signing convention exists for county routes in Arkansas. Many counties do not sign the county road numbers, relying instead on names posted on traditional "blade" street signs.

Forest routes[edit]

The U.S. Forest Service maintains Federal Forest Highways in Arkansas within the National Forests of Arkansas. As of January 2017, the total mileage of these roads is 285.452 miles (459.390 km).[c] Almost all Forest Roads are gravel or dirt, leading to campgrounds, maintenance areas, or trails.[d]

Levee roads[edit]

Levee roads in Arkansas are owned and maintained by levee authorities. Most of these routes are narrow, unpaved paths atop a levee to provide access for levee maintenance. Levee roads are mostly located in eastern Arkansas, especially along the Mississippi River.

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ "While the Highway 9 project was still underway, I told [State Representative] Olen Fullerton that we were going to run into some [political] trouble if we didn't start some construction in other parts of [Conway] [C]ounty. He understood the situation and over the next three years we got construction going in every direction" - Conway County Sheriff Marlin Hawkins.[17]

- ^ For 231,529; Against, 78,291[19]

- ^ Calculated by sorting all roads by Road Class = FE (Federal) and summing Length field.[28]

- ^ Calculated by sorting all roads by Road Class = FE (Federal) and summing Length field depending upon the value in Road Surface Type field (P, Paved or U, Unpaved). Results are 259.386 miles of unpaved roads (90.9%) and 26.066 miles (9.1%) of unpaved.[28]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d "[Arkansas] State Highways 2009 (Database)." April 2010. AHTD: Planning and Research Division. Database. Archived 2011-07-07 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved April 11, 2011.

- ^ McLaren, Christie. "Arkansas Highway History and Architecture, 1910-1965." Article. Archived 2011-06-02 at the Wayback Machine Page 4. Retrieved August 19, 2010.

- ^ Cook, Larry (1977). The good roads movement: the Arkansas experience, 1900-1923 (Thesis). Fayetteville, Arkansas: University of Arkansas. p. 2. OCLC 55602647.

- ^ Cook, Larry (1977). The good roads movement: the Arkansas experience, 1900-1923 (Thesis). Fayetteville, Arkansas: University of Arkansas. p. 4. OCLC 55602647.

- ^ McLaren, Christie. "Arkansas Highway History and Architecture, 1910-1965." Article. Archived 2011-06-02 at the Wayback Machine Page 5. Retrieved August 19, 2010.

- ^ McLaren, Christie. "Arkansas Highway History and Architecture, 1910-1965." Article. Archived 2011-06-02 at the Wayback Machine Page 7. Retrieved August 19, 2010.

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- ^ "Johnson III" (2019), p. 8.

- ^ a b McLaren, Christie. "Arkansas Highway History and Architecture, 1910-1965." Article. Archived 2011-06-02 at the Wayback Machine Page 9. Retrieved August 19, 2010.

- ^ Arkansas State Highway and Transportation Department: Planning and Research Division, Policy Analysis Section (2010). "Development of Highway and Transportation Legislation in Arkansas: A Review of the Acts Relative to Administering and Financing Highways and Transportation in Arkansas" (PDF). Little Rock: Arkansas Department of Transportation. p. 13. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 6, 2020.

- ^ McLaren, Christie. "Arkansas Highway History and Architecture, 1910-1965." Article. Archived 2011-06-02 at the Wayback Machine Page 10. Retrieved August 19, 2010.

- ^ a b c "The Public Roads of Arkansas and their Use." (Report to Committee on Roads and Highways of the Legislative Council) Arkansas State Highway Commission. July 1956.

- ^ "Map of State of Arkansas Showing System of Primary and Secondary Federal Aid Roads and Connecting State Roads and Progress of Improvements." December 31, 1924. Arkansas State Highway Department. Map. Archived July 7, 2011, at the Wayback Machine Retrieved March 12, 2011.

- ^ McLaren, Christie. "Arkansas Highway History and Architecture, 1910-1965." Article. Archived 2011-06-02 at the Wayback Machine Page 13. Retrieved August 20, 2010.

- ^ McLaren, Christie. "Arkansas Highway History and Architecture, 1910-1965." Article. Archived 2011-06-02 at the Wayback Machine Page 10. Retrieved August 20, 2010.

- ^ a b c "Governors" (1995), p. 212.

- ^ Hawkins, Marlin; Williams, C. Fred (1991). How I Stole Elections : the Autobiography of Sheriff Marlin Hawkins. Morrilton, AR: Publisher not identified. p. 175. ISBN 9780892212163. LCCN 91-66559. OCLC 25029004.

- ^ a b "Governors" (1995), p. 220.

- ^ Arkansas State Highway and Transportation Department: Planning and Research Division, Policy Analysis Section (2010). "Development of Highway and Transportation Legislation in Arkansas: A Review of the Acts Relative to Administering and Financing Highways and Transportation in Arkansas" (PDF). Little Rock: Arkansas Department of Transportation. p. 92. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 6, 2020.

- ^ "Appendix H: State Highway System Mileages • 1923 - 1991". Historical review: Arkansas State Highway Commission and Arkansas State Highway and Transportation Department, 1913-1992 (PDF). Vol. 2. Little Rock, Arkansas: Arkansas State Highway and Transportation Department. April 2004. pp. 252–253.

- ^ System Information and Research Division, Asset Management Section (2010). "Road and Street Mileage Report" (Database). Little Rock: Arkansas State Highway and Transportation Department. Retrieved February 8, 2020.

- ^ System Information and Research Division, Asset Management Section (2015). "Road and Street Mileage Report" (Database). Little Rock: Arkansas State Highway and Transportation Department. Retrieved February 8, 2020.

- ^ a b McLaren, Christie. "Arkansas Highway History and Architecture, 1910-1965" (PDF). p. 11. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 2, 2011. Retrieved August 20, 2010.

- ^ Brummett, John. "Arkansas highways — what a mess." Arkansas News. Article. Archived 2011-10-06 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved October 29, 2010.

- ^ Oman, Noel E. "State highway chief to retire from agency after 46 years' service." Arkansas Democrat-Gazette. pp. 1B, 6B. June 2, 2010.

- ^ Arkansas Atlas and Gazetteer (Map) (Second ed.). DeLorme.

- ^ "Fatality Facts 2019: State by state".

- ^ a b c "Arkansas Centerline File" (SHP). Little Rock: Arkansas GIS Office. January 4, 2017 [First published September 29, 2014]. Retrieved March 25, 2017.

- Smith, C. Calvin (1995) [1981]. Donovon, Timothy P.; Gatewood Jr., Willard B.; Whayne, Jeannie M. (eds.). The Governors of Arkansas (2nd ed.). Fayetteville, Arkansas: University of Arkansas Press. ISBN 1-55728-331-1. LCCN 94-45806. OCLC 988572226.

- Johnson III, Ben F. (2019). Arkansas in Modern America Since 1930 (2nd ed.). Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press. ISBN 978-1-68226-102-6. LCCN 2019000981.