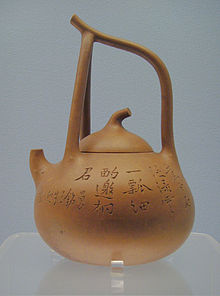

Yixing clay teapots (simplified Chinese: 宜兴; traditional Chinese: 宜興; pinyin: Yíxīng; Wade–Giles: I-Hsing), also called Zisha teapot (Chinese: 紫砂; pinyin: zǐshā; Wade–Giles: tsu sha; lit. 'Purple clay'),[1] are made from Yixing clay. This traditional style commonly used to brew tea originated in China, dating back to the 15th century, and are made from clay produced near Yixing in the eastern Chinese province of Jiangsu.

History[edit]

Archaeological excavations reveal that as early as the Song dynasty (10th century) potters near Yixing were using local "zisha" (紫砂 or 紫泥 ; literally, "purple sand/clay") to make utensils that may have functioned as teapots. According to the Ming dynasty author Zhou Gaoqi, during the reign of the Zhengde Emperor, a monk from Jinsha Temple (Golden Sand Temple) in Yixing handcrafted a fine quality teapot from local clay. Such teapots soon became popular with the scholarly class, and the fame of Yixing teapots began to spread.

20th century[edit]

Yíxīng teapots are actually made in nearby Dīngshān, also known as Dingshu,[2] on the west side of Lake Tai.[3] Hundreds of teapot shops line the edges of the town's crowded streets and it is a popular tourist destination for many Chinese. While Dīngshān is home to dozens of ceramics factories, Yíxīng Zǐshā Factory Number 1, which opened in 1958,[citation needed] processes a large part of the clay used in the region, produces fine pottery ware, and has a large commercial showroom. In addition to the better known teapots, tea pets, oil and grain jars, flower vases, figurines, glazed tiles, tables, ornamental rocks, and even ornamental waste bins are all manufactured in the community.[citation needed]

Use with tea[edit]

Yixing teapots are intended for puer, black, and oolong teas.[4] They can also be used for green or white teas; however, the heat retention characteristics of Yixing makes the brewing process extremely difficult; and in such cases, the water must be heated to no greater than 85 °C (185 °F), before pouring into the teapot. A famous characteristic of Yixing teapots is their ability to absorb trace amounts of brewed tea flavors and minerals into the teapot with each brewing. Over time, these accumulate to give each Yixing teapot its own unique interior coating that flavors and colors future brewings. It is for this reason that soap is not recommended for cleaning Yixing teapots, but instead, fresh distilled water and air drying. Many tea connoisseurs will steep only one type of tea in a particular Yixing teapot, so that future brewings of the same type of tea will be optimally enhanced. In contrast, brewing many different types of tea in a Yixing pot is likely to create a coating of mishmashed flavors that muddy the taste of future brewings.

Some Yixing teapots are smaller than their western counterparts as the tea is often brewed using the gongfu style of brewing: shorter steeping durations with smaller amounts of water and smaller teacups (compared to western-style brewing). Traditionally, the tea from the teapot is poured into either a small pitcher, from which it is then poured into a teacup that holds approximately 30 ml or less of liquid, allowing the tea to be quickly and repeatedly ingested before it becomes cooled, or into several teacups for guests.

Price[edit]

Prices can vary from a couple dozen to thousands of yuan.[5] A pot was auctioned in 2010 for 12.32 million yuan.[6] Generally, the price of Yixing teapots is dependent on factors such as age, clay, artist, style and production methods. The more expensive pots are shaped by hand using wooden and bamboo tools to manipulate the clay into form, while cheaper Yixing pots are produced by slipcasting.

Clay varieties[edit]

The type of clay used has a great impact on the characteristics of the teapot. There are three major colour types of Zisha clays: Purple, Red, and Beige.[7] Duan ni is a symbiosis of various clays and will normally turn into beige colour after firing. A subtype of the purple variety, called Tianqing clay, has historically been the most sought-after due to its rarity. It was said that Tianqing clay was exhausted, but it is suggested that it is not the case.[7] Tianqing clay was scarce only in the Ming dynasty as the excavation skills and technologies were limited. It was difficult for potters to excavate purple clay as the clay were normally located 30 meters below the surface. With the technology advancement, the excavation of purple clay has flourished, so has Tianqing clay.

Tianqing clay is distinguished from the generic purple type by:

- Its dark liver color after firing.[8]

- Its markedly sandier texture.

- Its higher permeability, leading to greater formation of a distinctive semitransparent patina.

- It can turn greenish after a period of usage and has a jade-like appearance[9] this change is distinguished from green coloration which is present from firing.

The teapot 風卷葵壺 made by Yang FengNian in the Qing dynasty was made from Tianqing clay. The teapot is now owned by the Yixing Ceramic Museum.

Some examples of Zisha teapots made with purple clay[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ "A Consumer's Guide to Buying a Yixing Zisha Teapot". teajourney. 31 August 2016.

- ^ Introducing Dīngshān from Lonely Planet. Retrieved 11 January 2013.

- ^ Introducing Lake Tai from Lonely Planet. Retrieved 11 January 2013.

- ^ "How to Season Yixing Teapots". ProfessionalTeaTaster.com. 29 January 2022. Retrieved 29 January 2022.

- ^ "Antique Yixing Teapots". MingWrecks.com. 17 September 2011. Retrieved 2 August 2012.

- ^ 北京紫砂壶拍卖创出1232万世界纪录(图)_新闻中心_新浪网 (in Chinese). Sina Corp. 9 June 2010. Retrieved 2 August 2012.

- ^ a b 李, 洪元 (2020). 宜興紫砂礦源圖譜 Yixing Zisha Kuangyuan Tupu (in Chinese). Beijing: 地質出版社. pp. 92–95, 590–599, 774. ISBN 978-7-116-11990-1.

- ^ 阳羡茗壶系 by 周高起, Ming dynasty.

- ^ 刘玉林,戴银法 《阳羡茗砂土》,四川美术出版社, 2013:84-88

Further reading[edit]

- K.S. Lo, et al., The Stonewares of Yixing: from the Ming period to the Present Day, (London: 1986, ISBN 0856671819).

- Wain, Peter, "A Taste of Transition: The Teapots of Yixing", Ceramic Review, 153, May/June 1995, pp. 42–45p

- Pan Chunfang, Yixing Pottery: the World of Chinese Tea Culture, (San Francisco, Long River Press: 2004, ISBN 159265018X).

External links[edit]

- Yixing Clay Teapot at China Online Museum

- "A Handbook of Chinese Ceramics". The Metropolitan Museum of Art Libraries. OCLC.

- "Zisha Teapots with National Living Treasure Zhou Gui Zhen and Zhu Jian Long". YouTube. Archived from the original on 13 December 2021. video of hand making a teapot