| |

| Company type | Public |

|---|---|

| Nasdaq: SWBI | |

| Industry | Manufacturing |

| Founded | 1852 |

| Founders | |

| Headquarters | , United States |

Key people | |

| Products | Firearms and ammunition |

| Revenue | |

| Total assets | |

| Total equity | |

Number of employees | |

| Website | smith-wesson |

| Footnotes / references Financials as of April 30, 2023[update].[1] | |

Smith & Wesson Brands, Inc. (S&W) is an American firearm manufacturer headquartered in Maryville, Tennessee, United States.

Smith & Wesson was founded by Horace Smith and Daniel B. Wesson as the "Smith & Wesson Revolver Company" in 1856 after their previous company, also called the "Smith & Wesson Company" and later renamed as "Volcanic Repeating Arms", was sold to Oliver Winchester and became the Winchester Repeating Arms Company. The modern Smith & Wesson had been previously owned by Bangor Punta and Tomkins plc before being acquired by Saf-T-Hammer Corporation in 2001. Smith & Wesson was a unit of American Outdoor Brands Corporation from 2016 to 2020 until the company was spun out in 2020.[2]

History[edit]

Volcanic Repeating Arms[edit]

Horace Smith and Daniel B. Wesson founded the Smith & Wesson Company in Norwich, Connecticut in 1852 to develop the Volcanic rifle. Smith developed a new Volcanic Cartridge, which he patented in 1854. The Smith & Wesson Company was renamed Volcanic Repeating Arms in 1855 and was purchased by Oliver Winchester. Smith left the company and returned to his native Springfield, Massachusetts, while Wesson stayed as plant manager with Volcanic Repeating Arms for eight months.[3] Volcanic Repeating Arms was insolvent in late 1856, after which it was reorganized as the New Haven Arms Company in April 1857 and eventually as the Winchester Repeating Arms Company by 1866.[4]

Smith & Wesson Revolver Company[edit]

As Samuel Colt's patent on the revolver was set to expire in 1856, Wesson began developing a prototype for a cartridge revolver. His research pointed out that a former Colt employee named Rollin White held the patent for a "bored-through" cylinder, a component he would need for his invention. Wesson reconnected with Smith, and the two partners approached White to manufacture a newly designed revolver-and-cartridge combination.[3] After Wesson left Volcanic Repeating Arms in 1856, he rejoined Smith to form the Smith & Wesson Revolver Company, which would become the modern Smith & Wesson company.[4]

Rather than make White a partner in their company, Smith & Wesson paid him a royalty of $0.25 on every revolver they made. This arrangement left White responsible for defending his patent, which eventually led to his financial ruin, while it was very advantageous for Smith & Wesson.[3]

19th century[edit]

Smith & Wesson's revolvers came into popular demand with the outbreak of the American Civil War as soldiers from all ranks on both sides of the conflict made private purchases of the revolvers for self-defense.[5]

The orders for the Smith & Wesson Model 1 revolver outpaced the factory's production capabilities. In 1860 demand volume exceeded the production capacity, so Smith & Wesson expanded into a new facility and began experimenting with a new cartridge design more suitable than the .22 Short that it had been using.[5]

At the same time, the company's design was being infringed upon by other manufacturers, which led to numerous lawsuits filed by Rollin White. In many of these instances, part of the restitution came in the form of the offender being forced to stamp "Manufactured for Smith & Wesson" on the revolvers in question.[5]

White's vigorous defense of his patent caused a problem for arms makers in the United States at the time as they could not manufacture cartridge revolvers. At the war's end, the U.S. Government charged White with causing the retardation of arms development in America.[5]

Demand for revolvers declined at the close of the Civil War, so Smith & Wesson focused on developing arms suitable for use on the American frontier. In 1870 the company switched focus from pocket-sized revolvers to a large frame revolver in heavier calibers (.44 S&W American). The U.S. Army adopted this new design, known as the Smith & Wesson Model 3, as the first cartridge-firing revolver in U.S. service.

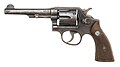

In 1899, Smith & Wesson introduced its most widely used revolver, the .38 Military & Police (also known as the Smith & Wesson Model 10). With over 6 million produced, it became the standard sidearm of American police officers for much of the 20th century.[6] An additional 1 million of these guns were made for the U.S. Military during World War II.[6]

20th century[edit]

The post-war periods in the 20th century were times of great innovation for the company. In 1935 Smith & Wesson released the .357 Registered Magnum, which was the first revolver chambered for .357 Magnum. It was designed as a more powerful handgun for law enforcement officers. The Registered Magnum started the "Magnum Era" of handguns. In 1957, when S&W started issuing model numbers to its revolvers, the revolver that had started as the Registered (and later the postwar .357 Magnum) became the Model 27. The high point was in 1955 when the company created the Smith & Wesson Model 29 in .44 Magnum. The Dirty Harry movies made this gun a cultural icon two decades later.[7]

In 1965, the Wesson family sold its controlling interest in Smith & Wesson to Bangor Punta, a prominent American conglomerate.[8] Over the next decade, Bangor Punta diversified the company's civilian sales to include related gun products (such as holsters) as well as offering additional police equipment (such as handcuffs and breathalyzers).[6] By the late 1970s these profitable moves made Smith & Wesson "the envy of the industry" according to Business Week.[9]

Despite these advantages, Smith & Wesson's market share began declining in the 1980s. As the war on drugs intensified in the United States, police departments all across the country replaced their Smith & Wesson revolvers with European semiautomatics (such as Glock, Sig Sauer and Beretta).[10] From 1982 to 1986 profits at the company declined by 41 percent[6]

In June 1987, Tomkins plc paid $112.5 million to purchase Smith & Wesson.[11] Tomkins modernized the production equipment and instituted additional testing which significantly increased product quality.[6] However, new gun sales in the United States lagged in the 1990s, some of which was attributed to the Federal Assault Weapons Ban of 1994. Also, there were numerous city and state lawsuits against Smith & Wesson. After the success of the Tobacco Master Settlement Agreement, municipalities thought they might be able to succeed through tort law against the gun industry as well.[12]

21st century[edit]

Clinton agreement[edit]

On March 17, 2000, Smith & Wesson made an agreement with U.S. President Bill Clinton under which it would implement changes in the design and distribution of its firearms,[13] in return for "preferred buying program" to offset the loss of revenue as a result of the anticipated consumer boycott.[14] The agreement stated all authorized dealers and distributors of Smith & Wesson's products had to abide by a "code of conduct" to eliminate the sale of firearms to prohibited persons, and dealers had to agree to not allow children under 18 (without an adult present) access to gun shops or sections of stores that contained firearms.[13]

In response, the National Rifle Association of America (NRA) and National Shooting Sports Foundation (NSSF) organised a campaign over the issue of smart guns.[15] Thousands of retailers and tens of thousands of firearms consumers boycotted Smith & Wesson.[16][17] CEO Ed Schultz, who negotiated the deal, was forced out in September of that year.[18] By December 2000, the company's stock price was 19 cents per share.[19] Smith & Wesson dropped its smart gun plans after nearly being driven out of business.[20]

Acquisition[edit]

On May 11, 2001, Saf-T-Hammer Corporation acquired Smith & Wesson Corp. from Tomkins plc for US$15 million, a fraction of the US$112 million originally paid by Tomkins.[21] Saf-T-Hammer assumed US$30 million in debt, bringing the total purchase price to US$45 million.[22][23] Saf-T-Hammer, a manufacturer of firearms locks and other safety products, purchased the company with the intention of incorporating its line of security products into all Smith & Wesson firearms in compliance with the 2000 agreement.

The acquisition of Smith & Wesson was chiefly brokered by Saf-T-Hammer President Bob Scott, who had left Smith & Wesson in 1999 because of a disagreement with Tomkins' policies. After the purchase, Scott became the president of Smith & Wesson to guide the 157-year-old company back to its former standing in the market.[24]

On February 15, 2002, the name of the newly formed entity was changed to Smith & Wesson Holding Corporation.[25]

Post-acquisition[edit]

In 2006 Smith & Wesson refocused its marketing on big box retailers, according to Smith & Wesson CEO Mike Golden in a 2008 conference call with investors.[26]

On November 7, 2016, Smith & Wesson Holding Corporation changed its name to American Outdoor Brands Corporation.[27] The next years saw increased scrutiny by some due to the use of its firearms in mass shootings such as the 2018 Stoneman Douglas High School shooting, in which a Smith & Wesson AR-15 style rifle, the semi-automatic M&P15 was used. The same weapon was used in the 2015 San Bernardino attack and the 2012 Aurora, Colorado shooting.[28][29][30][31]

In 2017 Smith & Wesson saw a severe contraction in its sales as units shipped to distributors and retailers declined 38.3%. The company was forced to lay off one-fourth of its manufacturing workforce.[32]

On August 24, 2020, American Outdoor Brands was spun-off from Smith & Wesson, with S&W retaining the stock ticker SWBI and American Outdoor Brands becoming a new publicly traded company on the NASDAQ as American Outdoor Brands, Inc.[2]

As of January 2022[update], SWBI had a market value of around $880 million, with revenues a little over US$1 billion [33]

Products[edit]

Cartridges[edit]

- .22 Short[34] — Based on the original .22 Black Powder Rimfire cartridge that the Model 1 was chambered in, but with a much more powerful smokeless powder charge.

- .32 S&W — Sometimes called .32 S&W Short[34]

- .32 S&W Long — Sometimes called .32 Colt New Police (a variation produced for the Colt New Police Revolver, as Colt did not want an association with their competitor)[34]

- .32-44 S&W, defined as .32 Caliber (true .32 caliber measures .323"), sole use in Model 3 Revolver to 1898.[35]

- .38 S&W — Sometimes called .38 Colt New Police (a variation produced for the Colt New Police Revolver, as Colt did not want an association with their competitor) and the 38/200 in England.[34]

- .38-44 S&W — There are two distinct loads with this designation. The first was intended for use in model 3 revolvers up to 1898. The second was a predecessor to the .357 Magnum. Using the latter load in a pre-1898 gun could cause serious injury.[35]

- .38 S&W Special[34] — Usually referred to as ".38 Special"

- .357 S&W Magnum[34] — Usually referred to as ".357 Magnum"

- .40 S&W[34] — Smith & Wesson developed the cartridge for the FBI, with releasing it and the Model 4006 pistol in 1990. Glock also released a pistol in .40, which, ironically, was adopted by the FBI in 1997 [36]

- .41 Remington Magnum — While Remington Arms developed the ammunition, Smith & Wesson made the first revolvers to chamber the cartridge.[34]

- .44 American[34]

- .44 Russian[34]

- .44 S&W Special[34]

- .44 Remington Magnum[34]

- .45 S&W Schofield[34]

- .460 S&W Magnum[37]

- .500 S&W Magnum[37] — designed to be the most powerful handgun in the world [38]

Early Handguns and Revolvers[edit]

-

Smith & Wesson Volcanic, caliber .31, between 1854 and 1855

-

Smith & Wesson Model 1 Second Issue, .22 rimfire

-

Smith & Wesson Army No 2, made 1863, caliber .32 Rimfire

-

Smith & Wesson No. 3, New Model, 44 Russian

-

Smith & Wesson Model 3, Cal. .44, between 1874 and 1878

-

Smith & Wesson .38 Special Model 1899 Military and Police Hand Ejector

-

Smith & Wesson M1917 cal. 45

-

Smith & Wesson Model 10 cal. 38

Smith & Wesson has produced revolvers over the years in several standard frame sizes. M refers to the small early Ladysmith frame, I to the small .32 frame, J to the small .38 frame, K to the medium .38 frame, L to the medium large .38 and .44 Magnum frame, and N to the largest .44 Magnum type frame.[39] In 2003, the even larger X frame was introduced for the .500 S&W Magnum.

|

|

|

|

|

Most Smith & Wesson revolvers have been equipped with an internal locking mechanism since the acquisition by Saf-T-Hammer. The mechanism is relatively unobtrusive, is activated with a special key, and renders the firearm inoperable. Most gun enthusiasts prefer to keep their gun unlocked.[52][53]

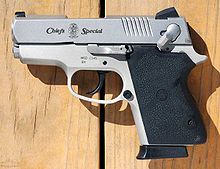

Semi-automatic pistols[edit]

In 1953 the U.S. Army was looking for a pistol to replace the Colt 1911A1.[40] To obtain a bid from the U.S. Government, Smith & Wesson began working on a design similar to the German Walther P38.[40] A year later the Army dropped its search and Smith & Wesson introduced its pistol to the civilian shooting market as the Model 39.[40]

The Model 39 would come to be known as a first-generation pistol. Since the Model 39 debuted, Smith & Wesson continuously developed this design into its third-generation pistols, which have now been discontinued. The first-generation models use a 2-digit model number, the second generation use 3 digits, and third-generation models use 4 digits.

- Smith & Wesson Bodyguard 380[54]

- Smith & Wesson Model 22A[54]

- Smith & Wesson SW22 Victory

- Smith & Wesson Model 39—first U.S.-designed double-action pistol in 9×19mm[40]

- Smith & Wesson Model 41[54]

- Smith & Wesson Model 52[54]

- Smith & Wesson Model 59—S&W's first high-capacity double-action pistol in 9 mm Parabellum[40]

- Smith & Wesson Model 61—Debuting in 1970, the pocket 'Escort' was a tiny automatic .22LR pistol, designed to be cheap and easily concealable. It was available in blued or nickel-plated with black or white plastic grips. Production stopped in 1973.[54]

- Smith & Wesson Model 78G[54]

- Smith & Wesson Model 1913 also known as Model 35

- Smith & Wesson Model 439— updated model 39[45]

- Smith & Wesson Model 459—S&W's entry into the US Army's XM9 program[45]

- Smith & Wesson Model 469[40]

- Smith & Wesson Model 645 second-generation large frame semi-auto in .45 ACP[54]

- Smith and Wesson 539

- Smith & Wesson Model 908[40]

- Smith & Wesson Model 909[45]

- Smith & Wesson Model 910[40]

- Smith & Wesson Model 915[45]

- Smith & Wesson Model 1006—stainless steel 10mm Auto[40]

- Smith & Wesson Model 1026 with a frame-mounted decocker[40]

- Smith & Wesson Model 4006[40]

- Smith & Wesson Model 4506 third-generation large frame semi-auto in .45 ACP [40]

- Smith & Wesson Model 5906[40]

Along with the myriad smaller configurations, the mid-sized 4516, 457, the Chiefs Special CS45, and the decocker equipped, 4546, 4566 and 4576, and the 45 TSW, the 4553, still being issued to the West Virginia State Troopers.[54]

For many of the second-generation models, the first digit identified the material used in the frame; thus the first digit of 4 indicated an alloy, the first digit of 5 indicated blued steel, and the first digit of 6 indicated stainless steel. For most of the third-generation models, the first two digits identified the calibre (except for 59/69 for 9mm), the last two digits were for the action style and the material, respectively. Action style numbers were typically 0 for the standard double/single-action and 4 for double-action-only. Material numbers were commonly 3 for aluminium, 4 for blued steel, and 6 for stainless steel.[citation needed]

Sigma series[edit]

Smith & Wesson introduced the Sigma series of recoil-operated, locked-breech semi-auto pistols in 1994 with the Sigma SW40F, followed by the Sigma SW9F 9 mm, which included a 17-shot magazine.[40] Glock initiated a patent infringement lawsuit against Smith & Wesson. The latter paid an undisclosed amount to settle the case and for the right to continue producing models in the Sigma line.[55] The gun frame is manufactured from polymer, while the slide and barrel use either stainless steel or carbon steel. In 1996, Smith & Wesson updated the Sigma by adding a compact model with a shortened barrel (from 41⁄2 to 4 inches) and again, in 1999, modified the series by changing the grip by adding checkering and adding an integral accessory rail for lights and laser targeting devices.[40]

SW99 Series[edit]

S&W reached an agreement with Walther to produce variations of the P99 line of pistols.[40] Branded as the SW99, the pistol is available in several calibres, including 9 mm, .40 S&W, and .45 ACP, and in both full size and compact variations. Under the terms of the agreement, Walther produced the frames, and Smith & Wesson produced the slide and barrel. The pistol has several cosmetic differences from the original Walther design and strongly resembles a hybrid between the P99 and the Sigma series.[40]

M&P Series[edit]

In 2005, Smith & Wesson debuted a new polymer-framed pistol intended for the law enforcement market. Dubbed the M&P (for Military and Police), its name was meant to evoke S&W's history as the firearm of choice for law enforcement agencies through its previous lineup of M&P revolvers. The M&P is a completely new design with no parts interchangeable with any other pistol including the Sigma. The new design not only looks completely different from the Sigma but feels completely different with 3 different backstraps supplied with each M&P. Many of the ergonomic study elements that had been incorporated into the Sigma and the SW99 were brought over to the M&P. The improved trigger weight and feel, and unique takedown method (not requiring a dry pull of the trigger) were meant to set the M&P apart from both the Sigma and the popular Glock pistols.

The M&P is available in 9×19mm, .40 S&W, 5.7x28mm, .22 WMR, and .357 SIG. Also, a .22 LR M&P was developed with Carl Walther and is made in Germany. A .45 ACP model was released in early 2007, after making its debut at the SHOT Show. In addition, compact versions are available in .22LR, 9×19mm, .40 S&W, .357 SIG, and .45 ACP. The .22LR Compact is made by Smith & Wesson in the United States. Subcompact versions are available in 9×19mm, .40 S&W and .45 ACP.

SD VE Series[edit]

Smith & Wesson introduced the SD VE series in 2012 to remake and improve the canceled Smith & Wesson SD. The SD VE design has an improved self-defense trigger and a comfortable, ergonomic, textured grip. The SD VE also features an improved stainless steel barrel and slide that the S.D. did not include. The Smith & Wesson SD VE is available in 9×19mm and .40 S&W calibers in either a standard-capacity version (16+1-round capacity for SD9 VE and 14+1 for SD40 VE) or the low-capacity version (10+1-round capacity for both calibers.)

In December 2023, Smith & Wesson announced the release of an updated version, dubbed the SD9 2.0. The new model features include an upgraded flat-face trigger and deeper slide serrations. There are other internal mechanical changes, but the new version can use the same magazines as the previous SD9 and Sigma 9mm pistols.[56]

SW1911 Series[edit]

In 2003, Smith & Wesson introduced their variation of the classic M1911 .45 ACP semi-automatic handgun, the SW1911. This firearm retains the M1911's well-known dimensions, operation, and feel while adding a variety of modern touches. Updates to the design include serration at the front of the slide for easier operation and disassembly, a high "beaver-tail" grip safety, external extractor, lighter weight hammer and trigger, as well as updated internal safeties to prevent accidental discharges if dropped. S&W 1911s are available with black finished carbon steel slides and frames or bead blasted stainless slides and frames. They are available with aluminium frames alloyed with scandium in either natural or black finishes. These updates have resulted in a firearm that is true to the M1911 design, with additions that would normally be considered "custom", with a price similar to equivalent designs from other manufacturers.

Smith & Wesson's Performance Center produces the top-of-the-line hand fitted competition version knowns as the P.C. 1911. While most 1911s run around 38 to 39 ounces (1,100 to 1,100 g), the PC 1911 is heavier, at approximately 41 ounces (1,200 g). The full-length guide rod adds some weight, and so does the add-on magazine well.

Rifles and carbines[edit]

During the early years of WW2, Smith & Wesson manufactured batches of the Model 1940 Light Rifle under request from the British Government.[57] It turned out to be a spectacular failure.[58]

In January 2006, Smith & Wesson reentered the rifle market with its M&P15 series of rifles based on the AR-15. Unveiled at SHOT Show 2006, the rifle debuted in two varieties: the M&P15 and the M&P15T. The two are basically the same rifle, chambered in 5.56 NATO, with the T model featuring folding sights and a four-sided accessories rail. These rifles were first produced by Stag Arms but marketed under the Smith & Wesson name.[59] Currently Smith & Wesson makes the lower receiver in-house while the barrel is supplied by Thompson/Center, a S&W company.

In May 2008, Smith & Wesson introduced its first AR-variant rifle in a caliber other than 5.56 NATO. The M&P15R is a standard AR-15 rifle chambered for the 5.45×39mm cartridge.[60] In 2009, it released the M&P15-22, chambered for .22 Long Rifle.[61]Smith & Wesson manufactured a line of bolt-action rifles called the i-Bolt.[62] These synthetic-stock rifles were available in .25-06, .270 Win, or .30-06 caliber. In late 2023, Smith & Wesson released a 9mm carbine called the Response. The controls on the Response are in standard AR format with a left-side safety lever and bolt release, right-side magazine release, and a rear-mounted charging handle. The stock and pistol grip are also AR-compatible.[63]

In February 2023, Smith & Wesson introduced a new folding pistol carbine, the M&P FPC. It is chambered in 9 mm, and comes equipped with three double-stack M&P pistol magazines, including one 17-round and two 23-round mags. It is optics-ready, has M&P pistol controls, and a folded length of 16⅜ inches.[64]

Submachine gun[edit]

In 1967 Smith & Wesson produced a 9mm submachine gun, hoping to capitalize on U.S. sales of the Israeli Uzi and H.K. MP5. It borrowed the magazine of the Carl Gustaf M/45 submachine gun (Kulsprutepistol m/45 or Kpist m/45, which had been popular with the U.S. forces in Vietnam as the "Swedish K") and made a similar side-folding stock. But the rest of the straight blowback weapon had no parts in common with the earlier Swedish gun. The S&W Model 76 submachine gun was made in limited numbers and was primarily used as a police weapon. Because all of them were made before 1986, many of them made it into civilian hands in the United States and are commonly used in submachine gun competition.[45]

Shotguns[edit]

Smith & Wesson bought patents and tooling for a pump-action shotgun design from Noble Manufacturing Co. in 1972 and produced it as the Model 916.[65] The guns were plagued by a variety of quality issues, including a recall due to a safety issue with barrels of the 916T (takedown) version rupturing.[66][67] The Model 916 was succeeded by the pump-action Model 3000 and the semi-automatic Model 1000; both were produced by Howa Machinery in Japan.[68][69] However, with the sale of the company to Tomkins plc, Smith & Wesson exited the shotgun market in the mid-1980s to return to their core market of handguns.

During the 1980s, the company released the Smith & Wesson AS, an assault shotgun which had a fully automatic capability.

In November 2006, Smith & Wesson announced that it would reenter the shotgun market with two new lines of shotguns, the break-open Elite Series and the semi-automatic 1000 Series, unveiled at the 2007 SHOT Show.[70] Both series were manufactured in Turkey.[71] Along with the new shotguns, the company debuted the Heirloom Warranty program, a first of its kind in the firearms industry. The warranty provides both the original buyer and the buyer's chosen heir with a lifetime warranty on all Elite Series shotguns.[70] The 1000 Series and Elite Series were both discontinued circa 2010.

In August 2021, S&W announced the first shotgun in its M&P line with the M&P12, a bullpup-style pump-action 12-gauge shotgun. The gun is chambered for 3-inch magnum shells and feeds through two independent magazine tubes. The tubes accept not only 3-inch shells, but also standard 23⁄4-inch shells and mini-shells.[72]

Other products[edit]

Smith & Wesson is also a manufacturer of restraints (handcuffs, leg irons, belly chains, prisoner transport chains). Smith & Wesson first manufactured handcuffs for the Peerless handcuff company which obtained the right to produce the first swinging-bow handcuffs patented by George A. Carney in 1912. Peerless did not have the facilities necessary for production so they contracted Smith & Wesson to manufacture the handcuffs for them.[73] When Peerless set up its own production plant, Smith & Wesson continued to produce Peerless-type handcuffs under their own brand.[74]

Smith & Wesson markets firearm accessories, safes, apparel, watches, collectibles, knives, collapsible batons, axes, tools, air guns, emergency light bars, and other products under its brand name.[citation needed]

John Wilson and Roy G. Jinks designed the Smith & Wesson model 6010 Bowie knife in 1971 and the 1973 Texas Ranger Bowie knife. Blackie Collins designed the subsequent model 6020 and 6060 Survival knife in 1974–1979. All of these limited-production and custom knives were made at the Springfield, Massachusetts, United States factory.[citation needed]

In October 2002, Smith & Wesson announced it had entered into a licensing agreement with Cycle Source Group to produce a line of bicycles designed by and for law enforcement. These bicycles had custom configurations and silent hubs.[75][76]

Smith & Wesson flashlights are available to the general public. They are designed and produced by PowerTech, Inc, in Collierville, Tennessee.[77]

Smith & Wesson has a line of wood pellet grills named after various pistol cartridges, such as .22 Magnum, .38 Special, .44 Magnum, .357 Magnum, and .500 Magnum.[78]

Smith & Wesson has entered into a licensing agreement with North Carolina-based Wellco Enterprises to design and distribute a full line of tactical law enforcement footwear.[79]

See also[edit]

- Daniel Leavitt – American firearms inventor

- Bangor Punta – defunct American conglomerate

References[edit]

Footnotes[edit]

- ^ a b "2023 Annual Report". U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. June 22, 2023. pp. 13, F-5, F-6. Retrieved September 12, 2023.

- ^ a b "American Outdoor Brands, Inc. Completes Spin-off from Smith & Wesson". August 25, 2020. Retrieved April 26, 2021.

- ^ a b c Boorman 2002, pp. 18–20.

- ^ a b Charles Winthrop Sawyer (1920). Firearms in American History. Charles Winthrop Sawyer.

- ^ a b c d Kinard 2004, pp. 114–117.

- ^ a b c d e "Smith & Wesson Corporation History". Funding Universe. Retrieved November 11, 2017.

- ^ JL, JB. "STUFF YOU GOTTA WATCH – Dirty Harry". thestuffyougottawatch.com. Archived from the original on April 20, 2018. Retrieved May 1, 2018.

- ^ [1] Bangor Punta Corporate Timeline

- ^ "Why the Firearms Business Has Tired Blood", Business Week, November 27, 1978, pp. 107, 110, 112

- ^ Donald J. Mihalek (May 21, 2014). "Duty Guns of America's Largest Police Departments". Archived from the original on June 21, 2014. Retrieved May 1, 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Richard W. Stevenson (May 23, 1987). "Smith & Wesson is sold to Britons". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 23, 2015. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ [Barrett, Paul M., "Attacks on Firearms Echo Earlier Assaults on Tobacco Industry", Wall Street Journal, March 12, 1999, pp. A1, A6.]

- ^ a b "Clinton Administration reaches historic agreement with Smith & Wesson". The White House Office of the Press Secretary. March 17, 2000. Archived from the original on July 24, 2001.

- ^ Tucker, Jennifer (July 2018), "Display of Arms", Johns Hopkins University Press, 59 Number 3: 738

- ^ Koszczuk, Jackie (March 23, 2000). "Nra Turns Against Smith & Wesson". Philly.com. Archived from the original on October 7, 2015.

- ^ Carter 2002, p. 542.

- ^ "What Happened When a Major Gun Company Crossed the NRA". PBS. Archived from the original on November 27, 2015. Retrieved May 1, 2018.

- ^ "A Major Gun Company Became An Industry Pariah After It Made Its Guns Safer". Business Insider. Archived from the original on December 30, 2012. Retrieved May 1, 2018.

- ^ "Smith & Wesson stock price history". Retrieved August 19, 2019.

- ^ "Will Obama's Action Create A Market For 'Smart' Guns?". NPR. Retrieved May 1, 2018.

- ^ Sweeney 2004, p. 22.

- ^ MCM staff (May 16, 2001). "Smith & Wesson Sold". Multichannel merchant. Retrieved November 10, 2015.

- ^ Wagner, Eileen Brill (May 14, 2001). "Saf-T-Hammer buys Smith & Wesson". Phoenix Business Journal. Retrieved November 11, 2015.

- ^ Tynan, Trudy (February 14, 2003). "It's big, it's bold: Gunmaker Smith & Wesson unveils hefty .50-caliber revolver". Kingman Daily Miner. p. 2B.

- ^ Smith & Wesson Holding Corporation (July 29, 2002). "Form 10-KSB". sec.gov. U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. p. 2. Retrieved August 20, 2015.

- ^ "Smith & Wesson Holding Corporation F4Q08 (Qtr End 04/30/08) Earnings Call Transcript". SeekingAlpha. June 13, 2008. Retrieved March 11, 2017.

We really have refocused our efforts on the big boxes. We put this new sales force in place, which was about 2 years ago, I guess, now. We focused on the larger dealers...

- ^ Handley, Lucy (December 13, 2016). "Gun maker Smith & Wesson to change name to American Outdoor Brands Corp". CNBC. Archived from the original on December 16, 2016. Retrieved January 1, 2017.

- ^ "Smith & Wesson Made the AR-15 Used in Florida School Massacre". Forbes. Retrieved March 25, 2018.

{{cite magazine}}: Unknown parameter|agency=ignored (help) - ^ Frankel, Todd C. (March 22, 2018). "A city that makes guns confronts its role in the Parkland mass shooting". Retrieved April 1, 2018.

- ^ "Smith & Wesson gun sales in free fall as Trump effect takes hold – BNN Bloomberg". March 2, 2018. Retrieved May 1, 2018.

- ^ Smith, Aaron (March 6, 2018). "Gun maker American Outdoor Brands: We won't be pushed into 'politically motivated' actions". Retrieved May 1, 2018.

- ^ Bomey, Nathan. "Gunmaker Smith & Wesson cuts jobs as sales plunge". CNBC. Retrieved March 25, 2018.

- ^ "Smith & Wesson Brands, Inc. (SWBI) Valuation Measures & Financial Statistics". finance.yahoo.com. Retrieved January 6, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Barnes & Skinner 2003, p. 528.

- ^ a b Sharpe, Philip B. Complete Guide to Handloading: A Treatise on Handloading for Pleasure, Economy and Utility. New York: Funk & Wagnalls Company.

- ^ See .40 S&W.[citation needed]

- ^ a b Barnes & Skinner 2003, pp. 312, 338.

- ^ 'The .500 S&W Magnum: Most Powerful Handgun Round In The World, NRA American Rifleman, June 24, 2020 noting role of Herb Belin in developing the concept of the SW 500 Magnum

- ^ Boorman 2002, pp. 44–45.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah Hartink 2002, pp. 87–88.

- ^ Supica & Nahas 2007, p. 72.

- ^ Supica & Nahas 2007, p. 80.

- ^ Hartink 2002.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Supica & Nahas 2007, p. 168.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Supica & Nahas 2007, p. 384.

- ^ a b c d Thompson & Smeets 1993, pp. 97–100.

- ^ Boorman 2002, pp. 117.

- ^ Boorman 2002, pp. 84.

- ^ a b c d e Supica & Nahas 2007, pp. 421–422.

- ^ a b c Supica & Nahas 2007, pp. 170.

- ^ The .500 S&W Magnum: Most Powerful Handgun Round In The World, NRA American Rifleman, June 24, 2020 noting role of Herb Belin in developing the concept of the SW 500 Magnum

- ^ Carter 2006, p. 210.

- ^ Ayoob, Massad (August 21, 2009). "More on the new crop from Smith & Wesson". Backwoods Home Magazine. Archived from the original on April 15, 2014. Retrieved April 14, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Supica & Nahas 2007, pp. 274.

- ^ Smith, Dan (April 2006). "Review: Smith & Wesson M&P .40 Cal Pistol". Retrieved December 17, 2008.

- ^ Knupp, Jeremiah (January 3, 2024). "New For 2024: Smith & Wesson SD9 2.0". American Rifleman. Retrieved April 1, 2024.

- ^ Supica, Jim; Nahas, Richard (November 14, 2016). Standard Catalog of Smith & Wesson. Iola, Wisconsin: F+W Media. pp. 409–410. ISBN 978-1-4402-4565-7.

- ^ "Smith & Wesson Light Rifle (Video)". March 3, 2014.

- ^ "Smith & Wesson Enters Long-Gun Market with M&P15 Rifles" (Press release). Smith & Wesson. January 18, 2006. Retrieved June 27, 2014.

- ^ Johnson, Richard (June 6, 2008). "Smith and Wesson M&P15R: New AR15 Platform Rifle and Uppers in 5.45×39". Guns Holsters And Gear. Retrieved November 11, 2015.

- ^ Rackley, Paul. "An AR Plinking Good Time". American Rifleman. Archived from the original on July 22, 2011.

- ^ Guthrie, J (January 3, 2011). "The S&W i-Bolt". ShootingTimes.com. Retrieved April 1, 2024.

- ^ Knupp, Jerimiah (October 21, 2023). "New For 2023: Smith & Wesson Response Carbine". AmericanRifleman.org. Retrieved April 13, 2024.

- ^ "New: Smith & Wesson M&P FPC Folding 9 mm Pistol Carbine". SSUSA.org. February 28, 2023. Retrieved April 1, 2024.

- ^ Petzal, David E.; Bourjaily, Phil (November 9, 2007). "Six Candidates for the Worst Shotguns of All Time". Field & Stream. Retrieved November 12, 2015.

- ^ "Gun barrels recalled". The Leader-Post. Regina, Saskatchewan. November 17, 1978. p. 1. Retrieved June 19, 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Defective gun barrels recalled". Detroit Free Press. Associated Press. November 17, 1978. p. 16D. Retrieved June 19, 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ Ayoob, Massad (July 1, 2007). "New and improved, old and proven: our handgun editor applauds Smith & Wesson's latest update for 2007". Guns Magazine. Retrieved June 19, 2020 – via The Free Library.

- ^ "Smith & Wesson Model 1000 Shotgun". American Rifleman. July 19, 2010. Retrieved June 19, 2020.

- ^ a b "Smith & Wesson Enters Shotgun Market" (Press release). Smith & Wesson. November 16, 2006. Retrieved June 27, 2014.

- ^ Hamre, Ryan (November 3, 2010). "Smith & Wesson's Model 1000". wildfowlmag.com. Retrieved June 26, 2020.

- ^ "Smith & Wesson® Launches New M&P12® Shotgun" (PDF) (Press release). Smith & Wesson Brands, Inc. August 17, 2021. Retrieved May 14, 2022.

- ^ Nichols 2002, p. 157.

- ^ Nichols 2002, p. 162.

- ^ "Smith & Wesson Enters Licensing Agreement With Cycle Source Group" (Press release). Smith & Wesson. October 3, 2002. Retrieved June 27, 2014.

- ^ "Smith & Wesson Bicycles Receive Wide Acclaim" (Press release). Smith & Wesson. April 16, 2003. Retrieved June 27, 2014.

- ^ Wagner 2009, p. 277.

- ^ Supica & Nahas 2007, pp. 390–393.

- ^ "Police Duty Boots Press Releases". www.policeone.com. Archived from the original on June 8, 2008.

Sources[edit]

- Barnes, Frank C.; Skinner, Stan (2003). Cartridges of the World (10th, Revised and Expanded ed.). Iola, Wisconsin: Krause Publications. ISBN 978-0-87349-605-6.

- Boorman, Dean K. (2002). The History of Smith & Wesson Firearms. Guilford, Connecticut: Globe Pequot Press, Lyons Press. ISBN 978-1-58574-721-4.

- Carter, Gregg Lee (January 1, 2002). Guns in American Society: An Encyclopedia of History, Politics, Culture, and the Law. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. p. 542. ISBN 978-1-57607-268-4.

- Carter, Gregg Lee (2006). Gun Control in the United States: A Reference Handbook. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. p. 210. ISBN 978-1-85109-760-9.

- Hartink, A.E. (2002). The Complete Encyclopedia of Pistols and Revolvers. Edison, New Jersey: Chartwell Books, Inc. ISBN 978-0-7858-1519-8.

- Kinard, Jeff (2004). Pistols: An Illustrated History of Their Impact. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. pp. 114–117. ISBN 978-1-85109-470-7.

- Nichols, Alex R. (July 31, 2002). A guidebook to handcuffs and other restraints of the world (Paperback). Kingscourt Publishing. ISBN 0-9531338-1-8.

- Supica, Jim; Nahas, Richard (2007). Standard Catalog of Smith & Wesson. Iola, Wisconsin: F+W Media. ISBN 978-0-89689-293-4.

- Sweeney, Patrick (December 13, 2004). The Gun Digest Book of Smith & Wesson. Iola, Wisconsin: Gun Digest Books. p. 22. ISBN 0-87349-792-9.

- Thompson, Leroy; Smeets, René (1993). Great Combat Handguns. London: Arms & Armour. ISBN 1-85409-168-9.

- Wagner, Scott W. (2009). Own the Night: Selection and Use of Tactical Lights and Laser Sights. Iola, Wisconsin: Gun Digest Books. p. 277. ISBN 978-1-4402-0371-8.

External links[edit]

- Official website

- Business data for Smith & Wesson: