Martin Agronsky | |

|---|---|

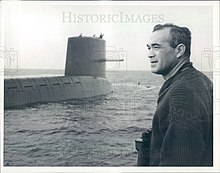

Agronsky in 1957 | |

| Born | Martin Zama Agrons January 12, 1915 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Died | July 25, 1999 (aged 84) |

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater | Rutgers University |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1936–1988 |

| Spouses |

|

| Children | 5 |

| Relatives | Agron family |

| Awards | See list |

| Signature | |

Martin Zama Agronsky (/əˈɡrɒn.skɪ/ ə-GRON-skih;[a] January 12, 1915 – July 25, 1999), also known as Martin Agronski,[4] was an American journalist, political analyst,[5] and television host. He began his career in 1936, working under his uncle, Gershon Agron, at the Palestine Post in Jerusalem, before deciding to work freelance in Europe a year later. At the outbreak of World War II, he became a war correspondent for NBC, working across three continents before returning to the United States in 1943 and covering the last few years of the war from Washington, D.C., with ABC.

After the war, Agronsky covered McCarthyism for ABC; fearless against McCarthy, he won a Peabody Award for 1952. When broadcast journalism moved away from radio, Agronsky returned to NBC, covering the news as well as interviewing prominent figures, including Martin Luther King Jr. as a young man. He returned to Jerusalem for a time and won the Alfred I. duPont Award in 1961 for his coverage of the Eichmann trial there. At the end of 1962, he recorded a documentary aboard the submarine USS George Washington which received an award at the Venice Film Festival. A prominent news reporter, and associate of John F. Kennedy, he extensively covered the 1963 assassination of Kennedy. The following year, he joined CBS, reportedly becoming the only journalist to work for all three commercial networks. With CBS, he moderated Face the Nation and won an Emmy for his interviews with Hugo Black, which marked the first television interview with a sitting Supreme Court Justice.

He left major companies in 1968, joining a local network to helm his own show, Agronsky & Co. A success, the show pioneered the "talking heads" news format. He added the Evening Edition, an interview format, to his show, which became prominent for its coverage of the Watergate scandal. Agronsky then joined PBS, swapping the Evening Edition for a longer interview show, Agronsky at Large. In his later career, he also acted as variations on himself in film and television. A graduate of Rutgers University, this institution would also award Agronsky an honorary Master of Arts and the Rutgers University Award (its highest honor), as well as inducting him into its Hall of Distinguished Alumni. He continued hosting Agronsky & Co. until 1988, when he retired from his over 50-year journalism career.

Early years[edit]

Martin Zama Agronsky[6] was born Martin Zama Agrons[7] in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on January 12, 1915, to Isador and Marcia (née Dvorin), Russian Jewish immigrants from Minsk in present-day Belarus.[8] Isador Agrons changed the family name from Agronsky to Agrons some time before Martin's birth, but Martin chose to use the original name when he began his journalism career.[7] Members of the family variously used the names Agronsky, Agrons, and Agron. In his career, Agronsky had a friendship with Harry Golden, who befriended and became a confidant to Isador.[9]

Agronsky's family moved to Atlantic City, New Jersey, when he was a young child, and he graduated from Atlantic City High School in 1932. He studied at Rutgers University in New Brunswick, New Jersey, graduating in 1936.[10] At Rutgers, Agronsky (still Agrons) was a member of Jewish fraternity Sigma Alpha Mu and represented them on the Interfraternity Council.[11][12][13]

Career[edit]

1936–1945: Early career and World War II[edit]

In 1936, upon his graduation, Agronsky was offered a job as a reporter for the English-language Palestine Post, precursor to today's Jerusalem Post, which was owned by his uncle, Gershon Agron, and moved to Jerusalem.[8][14] He left the newspaper in 1937[15] – he was uncomfortable working for Agron, calling it "pure nepotism",[16] as he "wanted to make it on his own" – and moved to Paris[17][16] to open a bookstore,[15] before becoming a freelance journalist covering the Spanish Civil War.[8] During his time in Europe, primarily Britain and France,[18] he freelanced for various newspapers and translated French stories into English for the International News Service;[19][16] he notably wrote an in-depth piece for Foreign Affairs magazine on the rise of anti-Semitism in Mussolini's Italy.[20][21] This article caught the attention of the Paris bureau of the New York Times, the newspaper at which Agronsky had long aspired to work.[16]

At the outbreak of World War II, he moved to Geneva in Switzerland, where he met Max Jordan, the National Broadcasting Company (NBC) bureau chief in Europe, who initially asked Agronsky to work freelance writing radio stories. Agronsky sold his stories to both NBC and the New York Times.[16] Despite having no broadcast journalism training, in April 1940 he was hired by NBC as a radio war correspondent when the company expanded their coverage.[8][16] Agronsky was conflicted in taking the job, as on the same day he had been offered a foreign assignment job by The New York Times, his dream job, but NBC was offering $250 per week plus expenses.[19][16] Jordan wanted to put together an NBC presence throughout Europe to cover the British conflict with Germany in the Balkans and tapped Agronsky to be the bureau chief there. Joining NBC as their Balkan correspondent, Agronsky became accredited by the British military and Royal Air Force (RAF).[16] He covered the war from all over the Balkans and much of Eastern Europe before opening a permanent NBC bureau in Ankara, the capital of neutral Turkey.[19] Although based in Ankara, Agronsky spent most of his time in Istanbul.[citation needed] He then became a foreign correspondent in Europe and North Africa, transferring to Cairo and being accredited to cover the British Eighth Army, in North Africa.[citation needed] Though NBC's European war coverage was not particularly celebrated, Agronsky "was a bright spot [...] distinguishing himself under fire in the Balkans, North Africa, and the Middle East."[8]

He was also accredited to cover "Malaya and the Dutch East Indies" in Southeast Asia;[18] when NBC's Asia correspondent John Young had to leave Singapore in November 1941 due to lack of British accreditation, Agronsky was sent in his stead, arriving from Ankara on December 22, 1941.[22] After Pearl Harbor and Singapore were bombed by Japan on December 7–8, 1941, Agronsky, now considered a seasoned war correspondent, was sent to the Pacific theater. His Pacific coverage would take him to Australia, where he was set to cover Douglas MacArthur's arrival in Melbourne.[8][23] In Singapore, Agronsky first stayed at the Raffles Hotel with other journalists, but left the week after Christmas 1941, on the day martial law was declared, to stay outside the city. He was not allowed to send news of the implementation of martial law, due to the short length of his broadcasts, and was subject to the same censorship as the local press; fellow journalist Cecil Brown was ultimately completely censored, and Agronsky was not permitted to telegraph this news for several days.[24] Brown had met Agronsky in Ankara in 1941, and described him then: "He is a jet-haired, zealous correspondent ... who gets almost all his information from the British Embassy. He works very hard ... and he and Burdett are busy cutting each other's throat to achieve what are euphemistically known as 'scoops.'"[14]

Agronsky was still in Singapore as the Japanese arrived, managing to catch the last plane out before the city was captured. He was then attached to MacArthur's troops and primarily covered Japan's conquest and the Allied retreat in Asia,[25][8][26] nearly being captured by Japanese soldiers in Kuala Lumpur and riding with the Dutch military on a Lockheed Lodestar for the final leg to Australia.[16] He came to national attention in 1942 due to his reporting in the Pacific, after broadcasting news that the Allies were struggling in Java due to expired munitions[2] and that the RAF had been turned away from Singapore as the Americans were not expecting them, suffering severe Japanese attacks in the confusion.[27] He flew with the RAF on some bombing missions.[16]

NBC was ordered to divest its radio network through the Red and Blue Networks in 1943, and Agronsky's contract was among those assigned to the "Blue" network, which NBC chose to divest. The associated assets became the American Broadcasting Company (ABC); smaller and less-renowned than the already-established networks, ABC did not have a television bureau.[8] Agronsky returned to the United States in 1943 when he joined ABC.[16] While other prominent war journalists found themselves able to take senior positions on television, Agronsky was instead assigned to Washington, D.C.,[8] where he did The Daily War Journal until the end of World War II.[citation needed][28][16]

1946–1955: ABC and McCarthy coverage[edit]

Agronsky maintained his prominence as a radio journalist for ABC following the war. An early proponent of civil rights, when president Harry S. Truman gave his speech to the NAACP in 1947, Agronsky was sceptical, suggesting that it was "a political gesture"; NAACP president Walter Francis White wrote to Agronsky to disagree, showing the NAACP's support for Truman.[29] In 1948, Agronsky helped to pioneer television coverage of American political conventions,[30][31][32] continuing to report from them with the first major television broadcasts in 1952.[33][34] In 1948, Agronsky had the most sponsors in broadcasting, with 104.[35]

He then took a principled stance against growing McCarthyism, also reporting on the Hollywood 10 and House Un-American Activities Committee. While many reporters gave milquetoast coverage of McCarthyism, said to be out of fear, Agronsky, like CBS's Edward R. Murrow after him, was openly critical of McCarthy and of the senators who enabled him. This bold stance saw Agronsky targeted with anti-Semitic hate mail and his show lose sponsors,[8][36][37][38] apparently pressured to leave by McCarthy so that Agronsky's show would be taken off air;[36] ABC, however, "congratulated him and took him to lunch", and encouraged him to continue with the criticisms.[8][37] The conversation reportedly went:[36][39]

Robert Kintner: They suggested I should talk to you [Agronsky] about the way you're reporting McCarthy. Are you going to change?

Agronsky: (flatly) No.

Kintner: That's what I thought you'd say. Keep it up.

He won the Peabody Award for 1952 for his coverage and criticism of Senator Joseph McCarthy's excessive accusations,[8] with the awarding committee noting that his ability to get "the story behind the story is distinctive".[40] He summarized McCarthy by saying: "Joe didn't take criticism very well."[16]

In 1953, Agronsky questioned president Dwight D. Eisenhower on investigating communism in churches and on book burning.[41] ABC then became the only major network to broadcast the 1954 Army–McCarthy hearings on television, growing their prominence[42] and "sinking McCarthy" due to the public exposure to his excesses.[43]

Agronsky also did a one-on-one discussion show at ABC, At Issue, which aired on Sunday evenings in 1953.[44] One prominent episode dealt with the tobacco crisis in 1953; new medical reports were appearing that suggested a link between smoking and lung cancer, and the tobacco industry was keen to encourage suppression of this information. One of few shows to cover the reports, Agronsky's program nevertheless "ended on a favorable note after conferences [with Hill & Knowlton]", the public relations firm hired by Big Tobacco.[45][46] At Issue was moved to Sunday afternoons as part of its block of public affairs programming in 1954, and ended later that year when ABC faced technical and sponsorship issues, scrapping its Sunday afternoon programming.[47] Agronsky was a member of the Radio and Television Correspondents' Association (RTCA) from 1948;[48] and became its chair, ending his term in 1954 (when Richard Harkness took the position) and becoming an ex officio member of its executive committee.[47]

1956–1963: Look Here, Eichmann trial, and NBC News[edit]

In 1956, with television now the leading broadcast medium, Agronsky left ABC (whose program was still weak) and returned to NBC, as a news correspondent.[8][16] From 1957 through 1964, starting with the Dave Garroway-hosted Today show, he did all the interviews out of Washington, D.C. In 1960, the show (and so Agronsky) began interviewing executive Secretaries. During this period his reputation grew.[8][NBC 1] He also hosted the one-on-one interview show Look Here, where he interviewed, among others, John F. Kennedy as a senator,[38][49] and a young Martin Luther King Jr.[50][51] Agronsky interviewed King on multiple occasions, with King notably outlining his nonviolence beliefs and faith in God on Look Here.[52][53][54] Also speaking on God, an answer Kennedy gave to Agronsky on his faith – that he would "uphold the Constitution" above all – became a prolific quote he used throughout his presidential campaign.[55][56]

Agronsky covered the Eichmann trial, of Nazi war criminal Adolf Eichmann, in Jerusalem in 1961 for nine months from start to finish, for which he won the Alfred I. duPont–Columbia University Award. Agronsky's reports were broadcast daily in a segment of the Huntley-Brinkley Report[8] at 6:30 a.m. as special reports;[57] he interviewed Holocaust survivors as well as figures of interest in Israel and Germany.[58] There was much media attention given to the trial, but typically on the wider implications, with little focus on the case of Eichmann: Agronsky's updates, including a verdict interview on the Today show, were atypical in their regularity.[59] Agronsky called the assignment the "most moving" story of his career.[16] While in Jerusalem, he spoke to friend Richard C. Blum, expressing his stress; Blum said that Agronsky was the go-to reporter in D.C. for Israel affairs.[60] Also in 1961, Agronsky interviewed Freedom Riders in the United States as the group was formed,[61] and covered the Vienna summit.[16]

In December 1962, Agronsky and a film crew underwent Navy training and joined the submariners of the USS George Washington, part of the American Polaris program, undersea for almost three weeks during operational duty to film the documentary Polaris Submarine: Journal of an Undersea Voyage. It won a variety of awards, including a documentary award, the St Mark's Plaque – First Prize, at the 1963 Venice Film Festival.[NBC 2][16]

Agronsky began television coverage of the March on Washington in August 1963, at 8:30 a.m. on Today, giving a half-hour report. Coverage then continued in different bursts across networks;[62] Agronsky reported with Nancy Dickerson from the Washington Monument during the day.[NBC 3] This same month, NBC wrote that Agronsky's "incisive questioning of Cabinet members[,] Congressmen and other Washington [D.C.] officials, as well as visiting statesmen from abroad, often results in important newsbreaks in the next day's papers."[NBC 4] Later in 1963, Agronsky was given special permission to travel to Moscow to report on nuclear discussions, after NBC had been banned.[NBC 5] Upon his return, he gave audiences his opinions on US foreign policy based on what he had witnessed, saying in such a global political climate, no country could remain a bystander, encouraging the general population to not be apathetic.[63]

1963: Assassination of John F. Kennedy[edit]

In the four-day aftermath of the assassination of president John F. Kennedy, Agronsky was one of the senior journalists to lead the large television news coverage.[64][65] The coverage invented the breaking format of modern television news.[66] Sociologists from Columbia University, led by Herbert Gans, interviewed a selection of the on-air journalists covering the assassination shortly afterwards to assess its affects; many were questioned about showing emotion. Agronsky's response, saying a journalist cannot show emotion as it would be imposing feelings on the viewer, was later said to typify the view of the issue at the time. When pressed further on the matter by Gans, Agronsky added: "I wanted to cry, but you don't".[64] He was reported to be smoking as he delivered reports from Washington, D.C., during the coverage, while hiding his cigarettes from the camera.[66]

| Agronsky interviewing Governor Connally at his hospital bedside, November 27, 1963 | |

|---|---|

via Associated Press Archive on YouTube | |

Historian William Manchester wrote that shortly after the shooting, Agronsky telephoned Ted Kennedy to ask if he would be flying from D.C. to Dallas, one of limited communications Ted Kennedy received in the aftermath of his brother's assassination due to telephone lines overloading as people tried to call others to talk about the news.[67] Agronsky covered Kennedy's lying in state on the Today show. He noted that he had also covered the funeral of Franklin D. Roosevelt, describing the different mood by explaining that people mourning Kennedy seemed moved by his unfulfilled potential.[68] On November 27, 1963, five days after the assassination, Agronsky conducted an interview with Texas governor John Connally from his bedside in Parkland Memorial Hospital. Connally, to whom Agronsky was a good friend, had been riding in the seat ahead of Kennedy and was wounded.[69][70] As Connally recovered, the press were desperate to hear his story, but his aides deemed him too weak to face a conference. Instead, the combined press accepted the proposal to use a single reporter as a pool, with all networks carrying the interview live. Connally's office chose Agronsky to be their reporter; he was found in Arlington National Cemetery late the night before and took a midnight flight to Dallas.[71]

Agronsky had interviewed Kennedy in life, with segments re-run on the 20th anniversary of the assassination in television documentary Thank You, Mr. President,[72] and co-authored and edited the 1961 book Let Us Begin: The First 100 Days of the Kennedy Administration.[73][74]

1964–1969: CBS[edit]

Agronsky moved to CBS in 1964. While there he held positions as the CBS bureau chief in Paris and moderator of Face the Nation. In 1969 he won an Emmy Award for his CBS News Special Reports television documentary Justice Black and the Bill of Rights or Justice Black and the Constitution, the first television interview with Supreme Court Justice Hugo Black, about Black's views on incorporation of the Bill of Rights.[8][16] This was rebroadcast in 1971.[75][76]

From 1968 to 1969, Agronsky was the Paris bureau chief for CBS.[16]

1969–1988: Eponymous programs[edit]

Agronsky & Company[edit]

Agronsky became a news anchor for WTOP-TV in Washington, D.C., in 1969, and in 1970 became host of the political discussion television program Agronsky & Company, produced by the same station. The format had Agronsky introduce a short segment on the news with political reporters. Shortly afterward, Agronsky left the local evening news and Agronsky & Company became a stand-alone weekly show produced and syndicated by Post-Newsweek stations (WTOP's then-owner). The show was syndicated nationally by Post-Newsweek to local stations and the Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) nationally, including WETA in D.C.[77] It was syndicated, in 1981, to twenty-five television stations, and Mutual Broadcasting System began carrying a radio format of the show in October 1981.[16]

In the 1970s and 80s, Agronsky also moderated a radio show, European Perspectives, tackling international news with foreign correspondents based in Washington on the panel.[16]

Broadcasting magazine noted in 1981 that Agronsky "still finds himself in the center of most of the biggest stories of the day."[16] He hosted Agronsky & Company until he retired in January 1988, and it proved to be one of the biggest successes of his career.[77] It was renamed Inside Washington upon Agronsky's retirement, and was hosted by Gordon Peterson until it ended in 2013.[78]

The show generally is credited as having invented the preeminent roundtable ("Talking Heads") discussion format for public affairs and political television shows that feature prominent journalists discussing current events and offering their opinions about them. Agronsky & Company did not have the spirited arguments and shouting that came to characterize many of its imitators, however. Its regular panelists included Hugh Sidey of Time magazine, Peter Lisagor of the Chicago Daily News, and columnists Carl Rowan, James J. Kilpatrick, Elizabeth Drew, and George Will. Although some of the liberal-versus-conservative argumentation now common on American public affairs shows began with pointed arguments between Agronsky & Company panelists, Agronsky himself always exerted a calming influence. The show was held in generally high regard; Ted Kennedy once said that "everybody who is in public life watches Agronsky."[10] In a celebrated essay for The New Republic, liberal pundit Michael Kinsley lampooned the program as "Jerkofsky and Company."

It had been at the forefront of the changing face of journalism in format and in terms of personalities, particularly the rise of "buckraking", with its panelists becoming national figures and often sought-after as public speakers in later years.[79] In 1986, it was overtaken in ratings by John McLaughlin's copycat show The McLaughlin Group; the major difference was said to be that "the pace of McLaughlin and its air of personal enmity give viewers the sense that they are watching genuine insider banter."[79]

After Agronsky's death, Agronsky & Co. commentator Hugh Sidey told the American Journalism Review of the show:[77]

I think the first thing is, it was first of its particular nature... So it had its own flavor... And Martin was its patriarch... He was a true shoe-leather reporter... I can remember many a program when we came straight from reporting the story... We came right out of the trenches. I'm not saying that doesn't happen now... but not with the same frequency... I would often come from being with the president... Show business had really not invaded our world back then... The idea was not to shout down anybody... I think another reason for its success was the nature of the times... We had real, real problems, explosive problems, security problems--and the discussions, I think, reflected that gravity... Compared to today... the kind of melding here between entertainment and journalism... The nature of those times was quite different, and I think that helped out the program a great deal as well as the people on it.

Martin Agronsky's Evening Edition[edit]

In 1970, in addition to hosting Agronsky & Company once a week, Agronsky started a five-night-a-week half-hour interview show, Martin Agronsky's Evening Edition, produced by Eastern Educational Network.[80][81] An early daily news program,[80] it became much-viewed during the Watergate scandal.[82] Richard Nixon reportedly watched the show avidly, sending Agronsky notes on his coverage.[8] Evening Edition extensively covered Nixon's presidency, including the Cold War détente and Vietnam War.[81] Evening Edition aired nightly and was on before, during and after the Watergate break-in hearings broadcast on PBS that led, ultimately, to Nixon's resignation on August 9, 1974.[8] Evening Edition went off the air in late 1975. Due to PBS experiencing "escalating program costs", it cut many shows going into 1976, including Evening Edition.[83]

Though Agronsky had been on coast-to-coast stations for many years, the relatively local programming which he headlined "did much to make Agronsky an influential national figure."[8]

Agronsky At Large[edit]

For PBS, Agronsky and Paul Duke interviewed president Gerald Ford in 1975.[84] Agronsky then did a one-hour interview show weekly on PBS during 1976 titled Agronsky at Large, where he interviewed such guests as Alfred Hitchcock and Anwar Sadat shortly before the Egyptian leader's assassination.[77] He also interviewed Muhammad Ali and George F. Kennan, a recording of which is held in the American Archive of Public Broadcasting's Peabody Awards collection.[85]

Interviewing Jody Powell, president Jimmy Carter's press secretary, in 1977, Agronsky suggested that the "honeymoon" period between the media and new presidents had been effectively curtailed following the Vietnam War and Watergate.[86]

Impact and legacy[edit]

During his 52-year journalism career (print from 1936 to 1940 and radio and television from 1940 to 1988) Agronsky worked for all three commercial networks in the United States.[8] He is believed to be the only broadcast journalist/commentator to have worked for all three, and is the only person to work for all three and PBS. He was the first television reporter to interview a sitting Supreme Court Justice.[87]

The moderator-led panel discussion format of news shows was, in 1984, described as "Martin Agronski style".[4] Agronsky & Company pioneered the "talking heads" news format.[87]

His papers, containing approximately 30,000 items, are held in a collection in the Library of Congress.[88][89]

Personal life[edit]

Profiling him for his Peabody win, Newsweek noted that Agronsky was a figure, being 5' 11" and dark-haired.[90] He married Helen Smathers on September 1, 1943.[91] Smathers was a United States Army nurse whom he met in 1942 while covering MacArthur in Melbourne.[92] Agronsky returned to the U.S. in March 1943,[8] whereupon he expedited Smathers's return. They were married in Baltimore, Maryland, at City Hall, grabbing a stranger off the street to be their witness.[citation needed] They went on to have four children: Marcia, Jonathan, David, and Julie.[8] He built a modernist house for his family in Washington, D.C. in 1951, though grew sick of the style by 1953.[90] In 1964, his home set on fire, suffering $35,000 worth of damage, and he broke his heel jumping from the second floor porch to get out.[93] Helen died on February 18, 1969, of cancer.[94] Agronsky then married Sharon Hines on April 22, 1971;[16] the marriage produced one child, Rachel. The American National Biography says that Agronsky and Hines divorced after fifteen years.[8] He died at his Rock Creek Park home in Washington, D.C., on July 25, 1999, of congestive heart failure. He was 84.[77]

Agronsky's son Jonathan Ian Zama Agronsky[95][96] is an American journalist and biographer. He attended St. Albans School in Washington, D.C.,[95] before studying English at Dartmouth College; enrolling in 1964,[97] he failed his studies twice before graduating with an AB in 1971. He used his studentship to avoid the draft for the Vietnam War, something about which he has expressed embarrassment, despite disagreeing with the war. He began professionally writing in 1967.[96] Though he followed his father's career, he had planned to be a college football player, joining a team at the age of eight and playing varsity halfback at prep school before joining and, ten days later, quitting the team at Dartmouth due to injury and malcontent.[97] Some of his earlier columns include contributing to the Penthouse Vietnam Veterans Advisor column in the 1970s and 1980s; he also wrote an article on Marion Barry in the magazine in 1991,[98] a topic on which he was an expert, publishing a book on Barry the same year.[99] At this time he worked for Voice of America in Washington, D.C.[97][100] He also wrote for the Washington City Paper.[101] As well as journalistic writing, he has written books and scripts for film and radio.[96] His book on Barry, The Politics of Race, was said by Kirkus Reviews to give "a careful, sober, and balanced account of Barry's decline and fall, and of a manipulation of the politics of race", but to "not explore the profound political cleavages evident in the result of Barry's trial".[100] He has written on other legal matters, including in 1987 on Miranda rights in ABA Journal.[102] In 2009 he was included in The Nine Lives of Marion Barry, a documentary film about the controversial politician.[103] In 2020, he began writing a book on David Whiting.[104]

Filmography[edit]

| Year | Title | Role | Notes | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1953–1954 | At Issue | – | Host; television | [105] |

| 1957–1958 | Look Here | – | Host; television | [106] |

| 1961 | It's Child's Play | [107] | ||

| 1961 | Nazareth to Bethlehem travelog | – | [107] | |

| 1962 | Polaris Submarine: Journal of an Undersea Voyage | – | Narrator; television documentary First aired in 1962 in the US and 1963 in the UK (on BBC Television) |

[NBC 2][108] |

| 1960–1964 | Today | – | Reporter; television | [8] |

| 1964 | Cuba: The Missile Crisis | – | Correspondent; NBC White Paper television special | [NBC 6] |

| 1964 | After Ten Years: The Court and the Schools | – | Correspondent; CBS News television special | [109] |

| 1962–1968 | The Huntley–Brinkley Report | – | Reporter; television | |

| 1964–1968 | CBS Reports | – | Reporter; television | |

| 1965–1968 | Face the Nation | – | Moderator; television | |

| 1971 | Vanished | Reporter | Television mini-series | |

| 1973 | What You Don't Know Can Kill You | – | Host; television special on President's Committee on Health Education | [110][111] |

| 1971–1976 | Martin Agronsky's Evening Edition | – | Host; television | [48] |

| 1976 | American Workmanship | [106] | ||

| 1979–1980 | And One to Grow On | [106] | ||

| 1981 | First Monday in October | TV Commentator | Film | [107] |

| 1983 | The National Financial Planning Quiz | [107] | ||

| 1983 | A Matter of Commitment | [107] | ||

| 1983 | Thank You, Mr. President | – | Archive footage; television | [72] |

| 1969–1987 | Agronsky & Co. | – | Host; television | [48] |

| 2018 | Hope & Fury: MLK, the Movement and the Media | – | Archive footage; television documentary |

Awards and honors[edit]

| Year | Association | Category | Work | Result | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1942 | Rutgers University | The Rutgers University Award | Coverage of World War II; described by Rutgers as "the most lucid and penetrating interpretation of world events during this war" (Agronsky was in Australia at the time: the award, the university's highest, was presented to his parents.) | Won | [18][112] |

| 1948 | Newspaper Guild | Heywood Broun Award | Career | Won | [73] |

| 1948 | Press Club of Atlantic City | National Headliner Award | Career | Won | [48] |

| 1949 | Society of Professional Journalists | Sigma Delta Chi Award | Career; Agronsky was also inducted into the Washington, D.C., chapter's Hall of Fame | Won | [88][113] |

| 1953 | Alfred I. duPont Award | Excellence in broadcast journalism | ABC radio | Special commendation | [47] |

| 1953 | Peabody Awards | Outstanding Radio News Coverage | Coverage of the excesses of Senator Joseph McCarthy; ABC radio (1952 awards presented in 1953); the citation read: "In this uneasy period of insecurity and fear, he has consistently and with rare courage given voice to the preservation of basic values in our democratic system." | Won | [6][114][37][40] |

| 1961 | Alfred I. duPont Award | Excellence in broadcast journalism | Eichmann trial coverage; NBC | Won | [6] |

| 1962 | Press Club of Atlantic City | National Headliner Award | Career | Won | [73] |

| 1962 | Overseas Press Club | Best Movie Photography from Abroad | Polaris Submarine: Journal of an Undersea Voyage; NBC (with Scott Berner) | Won | [115][NBC 2] |

| 1963 | CINE | Golden Eagle Award | Polaris Submarine: Journal of an Undersea Voyage | Won | [NBC 2] |

| 1963 | Venice Film Festival | Best Documentary: St. Mark's Plaque – First Prize | Polaris Submarine: Journal of an Undersea Voyage | Won | [73][NBC 2] |

| 1969 | Emmy Awards | Outstanding Program Achievement in the Field of News Commentary or Public Affairs | CBS News Special Reports: "Justice Black and the Bill of Rights" | Won | [8][75][116] |

| 1973 | Peabody Awards | Area of Excellence: Broadcasting | Agronsky and Co. | Submitted | [117] |

| 1974 | Peabody Awards | Area of Excellence: Broadcasting | Agronsky and Company | Submitted | [117] |

| 1975 | Peabody Awards | Area of Excellence: Broadcasting | Agronsky and Company | Submitted | [117] |

| 1976 | Peabody Awards | Area of Excellence: Broadcasting | Agronsky and Company | Submitted | [117] |

| Agronsky at Large: "An Interview with Muhammad Ali" and "An Interview with George Kennan" | Submitted | [85] | |||

| 1995 | Rutgers University | Hall of Distinguished Alumni | Career | Honored | [87] |

| Location | Date | School | Degree |

|---|---|---|---|

| New Jersey | 1949 | Rutgers University | Master of Arts (MA)[16] |

| New Hampshire | 1977 | Southern New Hampshire University | Doctor of Laws (LL.D)[118] |

In 1987, Agronsky gave the commencement address at San Diego State University.[119]

Notes[edit]

- ^ IPA and respelling per Peabody Awards introduction.[1] During Agronsky's life, there was debate on how his name should be pronounced.[2] A 1954 Who's Who provides in partial IPA that it should be /ɑː.ɡrɒnˈski/ ah-gron-SKEE.[3]

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ The Peabody Awards 1952.

- ^ Marquis-Who's Who 1954.

- ^ a b Campbell-Thrane 1984.

- ^ Roberts Forde & Ross 2011.

- ^ a b c Cox 2013.

- ^ a b Museum of the Jewish People 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y Carnes 2002.

- ^ Marlowe Hartnett 2015.

- ^ a b AP 1999.

- ^ Sanua 2018.

- ^ Rutgers University 1934.

- ^ Rutgers University 1935.

- ^ a b Bliss 2010, p. 119.

- ^ a b Husseini 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x Broadcasting Publications 1981.

- ^ Bliss 2010, pp. 119–120.

- ^ a b c Palcor 1942.

- ^ a b c Bliss 2010, p. 120.

- ^ Zander 2016.

- ^ Agronsky 1939.

- ^ Bliss 2010, p. 120–121, 123.

- ^ Bliss 2010, p. 123.

- ^ Bliss 2010, pp. 123–124.

- ^ Agronsky 1942.

- ^ Bliss 2010, p. 124.

- ^ United States Office of War Information Bureau of Intelligence 1942.

- ^ Bliss 2010, p. 155.

- ^ Fousek 2000.

- ^ Conway 2009.

- ^ Owen 1970.

- ^ Broadcasting Publications 1948, p. 78.

- ^ Bliss 2010, pp. 208–210, 253.

- ^ Martin 1952.

- ^ Broadcasting Publications 1948, p. 26.

- ^ a b c Bayley 1981.

- ^ a b c Bliss 2010, p. 243.

- ^ a b Benton & Minow 1964.

- ^ Shogan 2009.

- ^ a b Time 1953.

- ^ Eisenhower 1953.

- ^ Bender, Brown & Rosenzweig 2012.

- ^ Shafer 2005.

- ^ New York Times 1953.

- ^ Goodman 1994.

- ^ United States Congress House Committee on Energy and Commerce Subcommittee on Health and the Environment 1995.

- ^ a b c Codel 1954.

- ^ a b c d Ellis & Oleksiw 2010, p. 14.

- ^ IrishCentral 2018.

- ^ Agronsky & King 1957.

- ^ Agronsky 2016.

- ^ Joseph 2020.

- ^ Chappell 2013.

- ^ Shan Johnson 2006.

- ^ Jensen & Hammerback 1987.

- ^ Sarbaugh 1995.

- ^ Rittner & Roth 1997.

- ^ W.B. 1995.

- ^ Salomon 1963, pp. 256–257.

- ^ Geraci, Lage & Rubens 2014.

- ^ Holt et al. 2011.

- ^ Watson 1994.

- ^ Martin 1963.

- ^ a b Bodroghkozy 2013.

- ^ Dickerson 2013.

- ^ a b Rosenberg 1988.

- ^ Manchester 1996.

- ^ Downs & Agronsky 1963.

- ^ Agronsky 1963.

- ^ Connally & Agronsky 1963.

- ^ Read 2014.

- ^ a b Shales 1983.

- ^ a b c d Taft 2016.

- ^ Agronsky et al. 1961.

- ^ a b Benjamin 1988.

- ^ Philadelphia Daily News 1971.

- ^ a b c d e Robertson 1999.

- ^ Farhi 2013.

- ^ a b Weisberg 1986.

- ^ a b Sterling 2009.

- ^ a b Agronsky 2018.

- ^ Staff 1973.

- ^ Taishoff 1976.

- ^ Duke & Agronsky 1975.

- ^ a b Agronsky, Ali & Kennan 1976.

- ^ Grossman & Kumar 1979.

- ^ a b c Rutgers University 1995.

- ^ a b Ellis & Oleksiw 2010.

- ^ Agronsky 2010.

- ^ a b Newsweek Staff 1953.

- ^ Marquis-Who's Who 2000.

- ^ Amory 1959.

- ^ Plain Dealer 1964.

- ^ Plain Dealer 1969.

- ^ a b St. Albans School 1963.

- ^ a b c Agronsky 2015.

- ^ a b c Agronsky 1990.

- ^ Contento & Stephensen-Payne 2020.

- ^ Agronsky 1991.

- ^ a b Kirkus 2010.

- ^ DuRoss 2001.

- ^ Agronsky 1987.

- ^ BFI 2020.

- ^ Agronsky 2020.

- ^ Ellis & Oleksiw 2010, p. 7.

- ^ a b c Ellis & Oleksiw 2010, p. 10.

- ^ a b c d e Ellis & Oleksiw 2010, p. 11.

- ^ BBC Television 1963.

- ^ CBS News 1964.

- ^ AP 1973.

- ^ Plain Dealer 1973.

- ^ Plain Dealer 1942.

- ^ Society of Professional Journalists 2021.

- ^ The New York Times 1953.

- ^ Overseas Press Club 1962.

- ^ Brooks & Marsh 2009.

- ^ a b c d Hargrett Library 2011.

- ^ Southern New Hampshire University 2010.

- ^ Day 1987.

Sources[edit]

- Audio-visual media

- Agronsky, Martin; King, Martin Luther Jr. (1957). "Martin Luther King, Jr., on Nonviolence - The Civil Rights Act of 1964: A Long Struggle for Freedom | Exhibitions - Library of Congress". Library of Congress. Library of Congress. Archived from the original on November 2, 2021. Retrieved December 11, 2021.

- CBS News (1964). After Ten Years: The Court and the Schools. Dan Rather, Mike Wallace, Martin Agronsky, Charles Kuralt, Harry Reasoner (reporters). OCLC 45218587.

- Downs, Hugh; Agronsky, Martin (November 25, 1963). "Lee Harvey Oswald Shot On Camera". Today, NBC. Archived from the original on May 23, 2021. Retrieved December 11, 2021 – via YouTube.

- The Peabody Awards (1952). "Personal Award: Martin Agronsky for Outstanding Radio News Coverage". Archived from the original on September 3, 2021. Retrieved September 3, 2021.

- Read, Julian (January 6, 2014). "JFK's Final Hours In Texas". Sixth Floor Museum at Dealey Plaza. Archived from the original on December 11, 2021. Retrieved December 11, 2021 – via YouTube.

- Bibliography

- Agronsky, Martin (1939). "Racism in Italy". Foreign Affairs. 17 (2): 391–401. doi:10.2307/20028925. ISSN 0015-7120. JSTOR 20028925. Archived from the original on September 4, 2021. Retrieved September 4, 2021.

- Agronsky, Martin; Goldman, Eric Frederick; Hyman, Sidney; Ward, Barbara; Westfeldt, Wallace; Wolfert, Ira (1961). Agronsky, Martin; Grossman, Richard (eds.). Let Us Begin: The First 100 Days of the Kennedy Administration. Cornell Capa, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Elliott Erwitt, Burt Glinn, Constantine Manos, Inge Morath, Marc Riboud, Dennis Stock, Nicolas Tikhomiroff (photographers). Simon & Schuster. ASIN B000EAC928. OCLC 519702.

- Agronsky, Martin (November 28, 1963). "Transcript of Interview With Gov. Connally on Assassination; Asked About Thoughts Told About Death Close to President Rough Exterior". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 3, 2021. Retrieved September 3, 2021.

- Collections

- Agronsky, Martin (2010). Martin Agronsky papers. Library of Congress. Archived from the original on September 4, 2021. Retrieved December 11, 2021.

- Agronsky, Martin (January 4, 2016). "Interview by Martin Agronsky for "Look Here"". The Martin Luther King, Jr., Research and Education Institute, Stanford University. Archived from the original on September 30, 2021. Retrieved December 11, 2021.

- Agronsky, Martin (2018). "Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum White House Communications Agency Videotape Collection" (PDF). Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 19, 2021. Retrieved December 10, 2021.

- Agronsky, Martin; Ali, Muhammad; Kennan, George (1976). "Agronsky At Large; An Interview with Muhammad Ali". American Archive of Public Broadcasting. Retrieved February 27, 2022.

- Bender, Pennee; Brown, Joshua; Rosenzweig, Roy (2012). ""Have You No Sense of Decency": The Army-McCarthy Hearings". History Matters. Center for History and New Media Research, George Mason University. Archived from the original on September 12, 2021. Retrieved December 10, 2021.

- Benjamin, Burton (1988). "Find Aid: Burton Benjamin Papers, 1957-1988". Wisconsin Historical Society. Retrieved March 10, 2022.

- Connally, John; Agronsky, Martin (November 27, 1963). "Connally Interview with Martin Agronsky, November 27, 1963". Office of the Governor of Texas. Archived from the original on September 3, 2021. Retrieved September 3, 2021.

- Contento, William G.; Stephensen-Payne, Phil, eds. (2020). "Stories, Listed by Author". The FictionMags Index. Archived from the original on January 29, 2021. Retrieved November 24, 2020.

- Day, Thomas B. (1987). "San Diego State University Eighty-eighth Commencement". p. 8.

- Duke, Paul; Agronsky, Martin (August 7, 1975). "President's Media Interviews | Paul Duke and Martin Agronsky, Public Broadcasting System". Ford Presidential Library. Archived from the original on March 19, 2021. Retrieved December 10, 2021.

- Eisenhower, Dwight D. (1953). "Dwight D. Eisenhower: 1953: containing the public messages, speeches, and statements of the president, January 20 to December 31, 1953". Office of the Federal Register. pp. 111, 429–430.

- Ellis, Donna; Oleksiw, Dan (2010). "Martin Agronsky Papers Finding Aid" (PDF). Library of Congress. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 3, 2021. Retrieved September 3, 2021.

- Geraci, Victor; Lage, Ann; Rubens, Lisa (2014). "Conversations with Richard C. Blum: Businessman, Philanthropist, President Emeritus Board of Regents University of California" (PDF). Richard C. Blum. University of California, Berkeley. pp. 270–271. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 11, 2021. Retrieved December 10, 2021.

- Hargrett Library (2011). "George Foster Peabody Awards Collection, Series 2: Television Entries". Henry W. Grady College of Journalism and Mass Communication. University of Georgia.

- Holt, Lester; McGee, Frank; Lewis, John; King, Martin Luther Jr.; Nash, Diane; Seigenthaler, John; Kaplow, Herbert; Agronsky, Martin; Patterson, John; Kennedy, Robert; Ryan, Bill (April 5, 2011). "The Freedom Riders Video Transcript". Learning for Justice. Archived from the original on February 9, 2021. Retrieved December 11, 2021.

- Benton, William B.; Minow, Newton (July 18, 1964). "Oral History Interview" (PDF). John F. Kennedy Library. pp. 3–4.

- Museum of the Jewish People (2020). "Martin Agronsky family tree". Archived from the original on September 24, 2020. Retrieved September 11, 2020.

- Rutgers University (1934). Scarlet Letter (Yearbook). p. 103. Archived from the original on September 3, 2021. Retrieved September 3, 2021.

- Rutgers University (1935). Scarlet Letter (Yearbook). p. 179. Archived from the original on September 3, 2021. Retrieved September 3, 2021.

- Southern New Hampshire University (July 12, 2010). "Southern New Hampshire University Undergraduate Catalog 2010-2011". p. 187. Archived from the original on September 4, 2021. Retrieved September 4, 2021 – via Issuu.

- St. Albans School (1963). The Albanian (Yearbook 1963). p. 62 – via Newspapers.

- United States Congress House Committee on Energy and Commerce Subcommittee on Health and the Environment (1995). Regulation of Tobacco Products: Hearings Before the Subcommittee on Health and the Environment of the Committee on Energy and Commerce, House of Representatives, One Hundred Third Congress, Second Session. U.S. Government Printing Office. ISBN 978-0-16-046535-2.

- United States House Committee on Naval Affairs (1942). "Hearings Before the Committee on Naval Affairs of the House of Representatives on Sundry Legislation Affecting the Naval Establishment, 1941-[1942], Seventy-seventh Congress, First-[second] Session, Volume 22, Issues 171-305". pp. 2415–2426. Archived from the original on September 3, 2021. Retrieved September 3, 2021.

Mr. SHANNON. Do you know the correct pronunciation of the name of this gentleman that sent this message to all the world? What is his name?

Admiral BLANDY. As I pronounce it, it is Martin Agronsky.

Mr. SHANNON. What is his nationality?

Admiral BLANDY. That I do not know, sir.

Mr. SHANNON. [...] I have not found anybody that can pronounce his name, and I have not found anybody that knows anything about him. Maybe the chair-man knows how to pronounce it.

The CHAIRMAN. No, I cannot pronounce it. The only things I can pronounce are plain English names. These odd names are too hard for me. - United States Office of War Information Bureau of Intelligence (March 2, 1942). "Bungling". The New Republic. Martin Agronsky. p. 264.

- W.B., ed. (1995). National Jewish Archive of Broadcasting: Catalog of Holdings (PDF) (Second ed.). The Jewish Museum. p. 135. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 11, 2021. Retrieved December 10, 2021.

- Features

- Dickerson, John (November 23, 2013). "Inside LBJ's home the night after JFK died". CBS News. Archived from the original on September 3, 2021. Retrieved September 3, 2021.

- DuRoss, Greg (March 2, 2001). "All for One and One for All". Washington City Paper. Archived from the original on January 22, 2021. Retrieved November 24, 2020.

- Goodman, Michael J. (September 18, 1994). "Tobacco's Pr Campaign: The Cigarette Papers". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved March 11, 2022.

- Robertson, Lori (1999). "One of the Originals | Agronsky & Company for the five Post Newsweek stations". American Journalism Review (September 1999). Archived from the original on June 13, 2010. Retrieved October 23, 2009.

- Rosenberg, Howard (November 22, 1988). "Death of Kennedy & Birth of TV News". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on September 3, 2021. Retrieved September 3, 2021.

- Shafer, Jack (October 5, 2005). "Good Night, and Good Luck and bad history". Slate Magazine. Archived from the original on May 6, 2021. Retrieved December 10, 2021.

- Shales, Tom (November 13, 1983). "Camelot Recaptured". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on November 15, 2017. Retrieved September 3, 2021.

- Weisberg, Jacob (January 27, 1986). "The Buckrakers". The New Republic. ISSN 0028-6583. Retrieved January 27, 2022.

- Literature

- Agronsky, Jonathan I.Z. (November 1, 1987). "Meese vs. Miranda: The Final Countdown". ABA Journal: 86–92. ISSN 0747-0088.

- Agronsky, Jonathan I. Z. (1990). "Hanging Them Up". Dartmouth Alumni Magazine | The Complete Archive. Retrieved November 24, 2020.

- Agronsky, Jonathan I. Z. (1991). Marion Barry: The Politics of Race. Latham, NY: British American Pub. ISBN 978-0-945167-38-9. OCLC 21950714.

- Agronsky, Jonathan (2015). "His Guardian Angel". Dartmouth Alumni Magazine. Retrieved November 24, 2020.

- Agronsky, Jonathan (August 31, 2020). "Who Was That Masked Man? Something About David Whiting". Bright Lights Film Journal. Retrieved November 24, 2020.

- Amory, Cleveland (1959). International Celebrity Register. Celebrity Register. p. 8.

- Owen, Marie Bankhead (1970). The Alabama Historical Quarterly. Alabama State Department of Archives and History. pp. 28–31.

- Bayley, Edwin R. (1981). Joe McCarthy and the Press. Madison, Wis.: University of Wisconsin Press. pp. 193–195. ISBN 978-0-299-08623-7. OCLC 606186040. Archived from the original on December 11, 2021. Retrieved December 10, 2021.

- Bliss, Edward Jr. (2010). Now the News: The Story of Broadcast Journalism. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-52193-2.

- Bodroghkozy, Aniko (November 1, 2013). "Black Weekend: A Reception History of Network Television News and the Assassination of John F. Kennedy". Television & New Media. 14 (6): 560–578. doi:10.1177/1527476412452801. ISSN 1527-4764. S2CID 145492563.

- Broadcasting Publications (1948). Broadcasting, Telecasting.

- Broadcasting Publications (November 2, 1981). "Putting it on the Line: Profile: Martin Agronsky: a broadcast journalist who's covered the world". Broadcasting. p. 103.

- Brooks, Tim; Marsh, Earle F. (June 24, 2009). The Complete Directory to Prime Time Network and Cable TV Shows, 1946-Present. Random House Publishing Group. p. 204. ISBN 978-0-307-48320-1.

- Campbell-Thrane, Lucille (1984). Correspondence Education Moves to the Year 2000: Proceedings of the First National Invitational Forum on Correspondence Education. National Center for Research in Vocational Education, Ohio State University. pp. 79–86, 112. ISBN 978-0-318-17783-0. Archived from the original on September 3, 2021. Retrieved December 11, 2021.

- Carnes, Mark Christopher (2002). American National Biography: Supplement. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-522202-9. Archived from the original on June 16, 2021. Retrieved December 11, 2021.

- Chappell, Paul K. (2013). The Art of Waging Peace: a Strategic Approach to Improving our Lives and the World (First ed.). Westport, CT. ISBN 978-1-935212-68-3. OCLC 850200112.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Codel, Martin (1954). "Television digest with electronics reports".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Conway, Mike (2009). The Origins of Television News in America: The Visualizers of CBS in the 1940s. Peter Lang. pp. 236–237. ISBN 978-1-4331-0602-6.

- Cox, Jim (2013). Radio journalism in America: Telling the News in the Golden Age and Beyond. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-1-4766-0119-9. OCLC 839682810.

- Fousek, John (2000). To Lead the Free World: American Nationalism and the Cultural Roots of the Cold War. Univ of North Carolina Press. pp. 136–137. ISBN 978-0-8078-4836-4.

- Grossman, Michael Baruch; Kumar, Martha Joynt (1979). "The White House and the News Media: The Phases of Their Relationship". Political Science Quarterly. 94 (1): 37–53. doi:10.2307/2150155. ISSN 0032-3195. JSTOR 2150155.

- Husseini, Rafiq (April 30, 2020). Exiled from Jerusalem: The Diaries of Hussein Fakhri al-Khalidi. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 205. ISBN 978-1-83860-542-1.

- Jensen, Richard J.; Hammerback, John C., eds. (1987). In Search of Justice: The Indiana Tradition in Speech Communication. Rodopi. pp. 206–207. ISBN 978-90-6203-968-5.

- Joseph, Peniel E. (2020). The Sword and the Shield: the Revolutionary Lives of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr (First ed.). New York. ISBN 978-1-5416-1786-5. OCLC 1109808084.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Manchester, William (1996). The Death of a President, November 20-November 25, 1963 (1st ed.). New York: Galahad Books. pp. 198, 205. ISBN 0-88365-956-5. OCLC 36213931.

- Marlowe Hartnett, Kimberly (2015). Carolina Israelite: How Harry Golden Made Us Care about Jews, the South, and Civil Rights (First ed.). Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press. p. 238. ISBN 978-1-4696-2321-4. OCLC 905949528.

- Marquis-Who's Who (1954). Who's who in America: Supplement to Who's who, a current biographical reference service. p. 1249.

- Marquis-Who's Who (2000). Who was who in America. Marquis-Who's Who. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-8379-0232-6.

- Newsweek Staff (February 23, 1953). "Skillfull Reporter". Newsweek. Vol. 41, no. 8. p. 84.

- Rittner, Carol; Roth, John K. (1997). From the Unthinkable to the Unavoidable: American Christian and Jewish Scholars Encounter the Holocaust. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 174. ISBN 978-0-313-29683-3.

- Roberts Forde, Kathy; Ross, Matthew W. (2011). John C. Hartsock (ed.). "Radio and Civic Courage in the Communications Circuit of John Hersey's "Hiroshima"" (PDF). Literary Journalism Studies. 3 (2): 42. ISSN 1944-8988. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 11, 2021. Retrieved December 10, 2021.

- Salomon, George (1963). "The End of Eichmann: America's Response". The American Jewish Year Book. 64: 247–259. ISSN 0065-8987. JSTOR 23603688.

- Sanua, Marianne R. (2018). Going Greek: Jewish college fraternities in the United States, 1895-1945. p. 344.

- Sarbaugh, Timothy J. (1995). "Champion or Betrayer of His Own Kind: Presidential Politics and John F. Kennedy's "LOOK" Interview". Records of the American Catholic Historical Society of Philadelphia. 106 (1/2): 55–70. ISSN 0002-7790. JSTOR 44209773.

- Shan Johnson, Andrea (2006). Mixed up in the Making: Martin Luther King Jr., Cesar Chavez, and the images of their movements (PDF) (Thesis). University of Missouri-Columbia. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 11, 2021. Retrieved December 10, 2021.

- Shogan, Robert (2009). No Sense Of Decency: the Army-McCarthy Hearings: A Demagogue Falls and Television Takes Charge of American Politics. Lanham: Ivan R. Dee. pp. 88–89. ISBN 978-1-61578-000-6. OCLC 854520723.

- Sterling, Christopher H. (September 25, 2009). Encyclopedia of journalism. 6. Appendices. SAGE. p. 1157. ISBN 978-0-7619-2957-4.

- Taishoff, Sol, ed. (May 17, 1976). "PBS stations cut program buying". Broadcasting. pp. 62–63.

- Taft, William H. (2016). Encyclopedia of Twentieth-Century Journalists. Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon. p. 5. ISBN 978-1-317-40325-8. OCLC 913955667.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Watson, Mary Ann (1994). The Expanding Vista: American television in the Kennedy years. Durham: Duke University Press. p. 108. ISBN 0-8223-1443-6. OCLC 28721639.

- Zander, Patrick G. (2016). The Rise of Fascism: History, Documents, and Key Questions. Santa Barbara, California. p. 190. ISBN 978-1-61069-799-6. OCLC 932109927.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

- News

- Agronsky, Gershon, ed. (February 20, 1942). "Social & Personal". The Palestine Post. p. 2, column A – via National Library of Israel.

- AP (April 14, 1973). "Monday Special of the Week". North Hills News Record. North Hills, Pennsylvania. p. 29. Archived from the original on September 3, 2021. Retrieved September 3, 2021.

- AP (June 26, 1999). "Martin Agronsky, TV Commentator, Dies". The Seattle Times. AP, The Washington Post. Archived from the original on May 19, 2011. Retrieved January 16, 2015.

- Farhi, Paul (September 8, 2013). "After more than 40 years, 'Inside Washington' will go off the air". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved February 27, 2022.

- Martin, Joe (July 19, 1952). "ABC-TV Ingenuity Develops Fast, Punchy, Well-Balanced Continuity | ABC Radio Coverage: 40-Man Staff Provides Sound Reporting Team | ABC-TV Coverage: Web Does Punchy, Well-Balanced Job". Billboard. pp. 3, 9–10.

- Martin, Mary (October 22, 1963). "Agronsky Claims U.S. No Innocent Bystander" (PDF). The Skiff. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 11, 2021. Retrieved December 11, 2021.

- New York Times (August 5, 1953). "Television in Review; ' At Issue,' New Discussion Program, Seems Designed to Make Viewers Think". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on December 11, 2021. Retrieved December 10, 2021.

- Palcor (July 30, 1942). "Rutgers Prize for Martin Agronsky". The Palestine Post. p. 3, column D.

- Philadelphia Daily News (July 20, 1971). "Your TV scout reports". Philadelphia Daily News. p. 36.

- Plain Dealer (May 9, 1942). "Rutgers Cites Newsmen; Gives Highest Award to Clark Lee and Agronsky". Cleveland Plain Dealer.

- Plain Dealer (March 31, 1964). "N/A". Cleveland Plain Dealer.

- Plain Dealer (February 20, 1969). "N/A". Cleveland Plain Dealer.

- Plain Dealer (April 13, 1973). "Television Highlights". Cleveland Plain Dealer.

- Staff (June 22, 1973). "Weicker Defends Dean's Right To Tell His Story on Watergate". The New York Times. Associated Press. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 27, 2022.

- The New York Times (April 24, 1953). "AGRONSKY OF A.B.C. GETS NEWS AWARD; Peabody Citations Covering 9 Categories of Programming Also List Philharmonic". The New York Times. p. 35.

- Time (April 27, 1953). "Radio: Winners". Time. ISSN 0040-781X. Retrieved March 24, 2022.

- Trade press

- NBC (1963). N.B.C trade releases.

- NBC (1964). N.B.C trade releases.

- ^ Reports in NBC trade releases 1964:

- January 7, 1964: "'Today' Scores A Dozen Years Of TV Achievement".

- January 8, 1964: "Secretaries Dillon, Rusk, Celebrezze To Be First Guests As 'Today' Starts Fourth Year Of Interviews With Cabinet Members".

- ^ a b c d e August 5, 1963: "NBC News TV Program, "Polaris Submarine," Wins First Prize St. Mark's Plaque At 1963 Venice Film Festival". in NBC trade releases 1963.

- ^ Reports in NBC trade releases 1963:

- August 26, 1963: "Assignments Listed For NBC News' Comprehensive TV And Radio Coverage Of Civil Rights March"

- August 26, 1963: "Live Coverage Of Civil Rights March On Washington To Be Fed By NBC-TV (Via Telstar II) To 11 Eurovision Networks"

- August 28, 1963: "Comprehensive Reports, Interviews With Headline Personalities, And Multiple Pickup Points Provided NBC News With Thorough Coverage Of The Civil Rights March On Washington"

- August 29, 1963: "NBC News' Comprehensive TV Coverage Of March On Washington Spanned 17 Hours, With Excerpts Seen In Europe Via Telstar II"

- ^ August 28, 1963: "'Today' Reflects The Interesting And Important". in NBC trade releases 1963.

- ^ August 1, 1963: "NBC News Receives Soviet Permission To Send Two Correspondents And Camera Crew To Cover Signing Of Nuclear Test Ban Treaty in Moscow". in NBC trade releases 1963.

- ^ January 28, 1964: "'NBC White Paper' On 'Cuba: The Missile Crisis' Relates The Momentous Events Of 15-Day 1962 Period". in NBC trade releases 1964.

- Web

- BBC Television (1963). "Schedule - BBC Programme Index - January 22, 1963". BBC Genome. Archived from the original on September 3, 2021. Retrieved September 3, 2021.

- BFI (2020). "Jonathan Agronsky". Archived from the original on March 10, 2022. Retrieved November 24, 2020.

- IrishCentral (May 29, 2018). "Five ways JFK was a visionary leader remarkably ahead of his time". Retrieved February 28, 2022.

- Kirkus (2010). Marion Barry: The Politics of Race by Jonathan I.Z. Agronsky. Archived from the original on October 26, 2020.

- Overseas Press Club (1962). "Awards Recipients Archive". Archived from the original on June 28, 2021. Retrieved December 10, 2021.

- Rutgers University (1995). "Martin Agronsky". Rutgers University Alumni Association. Archived from the original on September 3, 2021. Retrieved September 3, 2021.

- Society of Professional Journalists (2021). "Society of Professional Journalists Washington, D.C., Hall of Fame". Washington, D.C., Pro SPJ Chapter. Archived from the original on November 6, 2021. Retrieved December 10, 2021.