| Inostrancevia | |

|---|---|

| |

| Mounted skeleton of I. alexandri (PIN 1758), exposed at the Museo delle Scienze, Trento, Italy | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Synapsida |

| Clade: | Therapsida |

| Clade: | †Gorgonopsia |

| Family: | †Gorgonopsidae |

| Subfamily: | †Inostranceviinae |

| Genus: | †Inostrancevia Amalitsky, 1905 |

| Type species | |

| †Inostrancevia alexandri | |

| Other species | |

| Synonyms | |

|

List of synonyms

| |

Inostrancevia is an extinct genus of large carnivorous therapsids which lived during the Late Permian in what is now European Russia and Southern Africa. The first-known fossils of this gorgonopsian were discovered in the Northern Dvina, where two almost complete skeletons were exhumed. Subsequently, several other fossil materials were discovered in various oblasts, and these finds will lead to a confusion about the exact number of valid species in the country, before only three of them were officially recognized: I. alexandri, I. latifrons and I. uralensis. More recent research carried out in South Africa has discovered fairly well-preserved remains of the genus, being attributed to the species I. africana. An isolated left premaxilla suggests that Inostrancevia also lived in Tanzania during the earliest Lopingian age. The whole genus is named in honor of Alexander Inostrantsev, professor of Vladimir P. Amalitsky, the paleontologist who described the taxon.

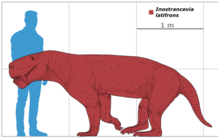

Inostrancevia is the biggest-known gorgonopsian, the largest fossil specimens indicating an estimated size between 3 m (9.8 ft) and 3.5 m (11 ft) long. The animal is characterized by its robust skeleton, broad skull and a very advanced dentition, possessing large canines, the longest of which can reach 15 cm (5.9 in) and probably used to shear the skin off its prey. Like most other gorgonopsians, Inostrancevia had a particularly large jaw opening angle, which would have allowed to deliver fatal bites.

First regularly classified as close to African taxa such as Gorgonops or rubidgeines, phylogenetic analyses published since 2018 consider it to belong to a group of derived Russian gorgonopsians, now being classified alongside the genera Suchogorgon, Sauroctonus and Pravoslavlevia. According to the Russian and South African fossil records, the faunas where Inostrancevia is recorded were fluvial ecosystems containing many tetrapods, where it turns out to have been the main predator.

Research history[edit]

Recognized species[edit]

During the 1890s, Russian paleontologist Vladimir Amalitsky discovered freshwater sediments dating from the Upper Permian in Northern Dvina, Arkhangelsk Oblast, northern European Russia. The locality, known as PIN 2005, consists of a creek with sandstone and lens-shaped exposures in a bank escarpment, containing many particularly well-preserved fossil skeletons.[3] This type of fauna from this period, previously known only from South Africa and India, is considered as one of the greatest paleontological discoveries of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.[4] After the preliminary reconnaissance of the place, Amalitsky conducts systematic research with his companion Anna P. Amalitsky.[3] The first excavations began in 1899,[5] and several of her findings where sent to Warsaw, Poland, in order to be prepared there.[6] The exhumations of the fossils then lasted until 1914, when the research stopped due to the start of the World War I.[7] The fossils discovered within the site will subsequently be moved to the Museum of Geology and Mineralogy of the Russian Academy of Sciences. All the fossils listed were not prepared, and more than 100 tons of concretions were promised for new discoveries by the museum in question.[3]

The multiple administrative activities and difficult conditions during Amalitsky's last years have severely hampered his fossil research, leading to his unexpected death in 1917. However, among all the fossils identified before his death are two remarkably complete skeletons of large gorgonopsians, cataloged PIN 1758 and PIN 2005/1578 (the latter of which would later be recognized as the lectotype of the genus).[8][9][10] After identification, he assigned the two specimens to a new genus, which he named Inostranzevia.[3] The first time when this name was used in scientific literature was in a work written by the British zoologist Edwin Ray Lankester, published in 1905.[11] Although Lankester credits Amalitsky for originating this generic name, he most likely had no information on whether or not the taxon had been formally described.[12] Five years later, in 1910, the Anglican clergyman Henry Neville Hutchinson added the specific name alexandri to the genus.[13] Hutchinson's proposal for a new name was probably not intentional for the same reason as Lankester.[12] This time, Amalitsky is credited only for providing the images of the fossil animal and not for the specific epithet.[13] Thus, the authorship of the word alexandri has as formal author Hutchinson.[12] The first formal descriptions of this gorgonopsian were only published posthumously in 1922, but the name of the genus and species were nevertheless kept.[3] Although the etymology of the genus and type species is not provided in the earliest-known descriptions of the taxon, the full name of the animal is named in honor of the renowned geologist Alexander Inostrantsev,[9] who was one of Amalitsky's teachers.[14] Amalitsky's article generally describes all the fossil discoveries made in the Northern Dvina, and not Inostrancevia itself, the article mentioning that further research on this gorgonopsian is subject to research.[3]

It was in 1927 that one of Amalitsky's colleagues, Pavel A. Pravoslavlev, published the first formal description of the genus. In his monograph he names several additional species,[a] and revises in detail the morphology of the two known skeletons of I. alexandri.[15] Of all the named species, only I. latifrons was the only one recognized as a clearly distinct species within the genus, being based on skulls discovered within Arkhangelsk Oblast as well as a very incomplete skeleton from the village of Zavrazhye, located in Vladimir Oblast.[8] The specific epithet latifrons comes from the Latin latus "broad" and frōns "forehead", in reference to the size and the more robust cranial constitution than that of I. alexandri. In his book, Pravoslavlev also changed the typography of the name "Inostranzevia" to "Inostrancevia".[15] This last term has since entered into universal usage and must be maintained according to the rule of article 33.3.1 of the ICZN.[16] Although Pravoslavlev's work was of major importance, more recent work requires that a re-examination of the skeletal anatomy of the genus is necessary in order to broaden the understanding of the animal's biology.[17]

| External picture | |

|---|---|

In 1974, Leonid Tatarinov described the third species, I. uralensis, based on rare remains of part of the skull from an individual smaller than the other two recognized species. The holotype specimen, cataloged PIN 2896/1, consists of a left basioccipital discovered in the locality of Blumental-3, in the Orenburg Oblast. The specific epithet uralensis refers to the Ural River, where the holotype specimen of the taxon was found.[9][18][16] However, due to its poor fossil preservation of this species, Tatarinov argues that it is possible that I. uralensis could belong to a new genus of large gorgonopsians without having a certain confirmation.[19]

The fourth known species, I. africana, was discovered from two specimens found between 2010 and 2011, respectively, by Nthaopa Ntheri and John Nyaphuli at Nooitgedacht Farm in the Karoo Basin, South Africa. The two known specimens, holotype NMQR 4000 and paratype NMQR 3707, are recorded in the Balfour Formation, and more specifically in the Daptocephalus Assemblage Zone, from where they are dated to between 254 and 251.9 million years ago.[2] The two specimens were mentioned in 2014 in the chapter of a work listing the discoveries made at Nooitgedacht.[20] It was in 2023 that Christian F. Kammerer and his colleagues publish a revision which unexpectedly confirmed that these specimens belonged to the genus Inostrancevia, which is a significant first, because the genus was previously reported only in Russia. However, these specimens have some differences with the Russian species, being classified in the newly erected species I. africana, the specific epithet referring to Africa, the continent from which the taxon lived. The article officially describing this animal is mainly concerned with the stratigraphic significance of the finds and is only a brief introduction to the anatomy of the new fossil material, the latter being subjects for a study to be published later.[2]

Formerly assigned species and synonyms[edit]

Due to the poor quality of preservation of some Inostrancevia fossils, several specimens were therefore incorrectly found to belong to separate taxa. Only four species are recognized today, with three (I. alexandri, I. latifrons and I. uralensis) from Russia and one (I. africana) from South Africa.[2]

In his 1927 monograph, Pravoslavlev names two additional species of the genus Inostrancevia: I. parva and I. proclivis.[15] In 1940, the paleontologist Ivan Yefremov expressed doubts about this classification, and considered that the holotype specimen of I. parva should be viewed as a juvenile of the genus and not as a distinct species.[16][21] It was in 1953 that Boris Pavlovich Vyuschkov completely revised the species named for Inostrancevia. For I. parva, he moves it to a new genus, which he names Pravoslavlevia, in honor of the original author who named the species.[22] Although being a distinct and valid genus, Pravoslavlevia turns out to be a closely related taxon.[8][16][23][24] Also in his article, he considers that I. proclivis is a junior synonym of I. alexandri, but remains open to the question of the existence of this species, arguing his opinion with the insufficient preservation of type specimens.[22] This taxon will be definitively judged as being conspecific to I. alexandri in the revision of the genus carried out by Tatarinov in 1974.[25]

Also in is work, Pravoslavlev names another genus of gorgonopsians, Amalitzkia, with the two species it includes: A. vladimiri and A. annae, both named in reference to the pair of paleontologists who carried out the work on the first specimens known of I. alexandri.[15] In 1953, Vjuschkov discovered that the genus Amalitzkia is a junior synonym of Inostrancevia, renaming A. vladimiri to I. vladimiri,[22] before the latter was itself recognized as a junior synonym of I. latifrons by later publications.[26][8] For some unclear reason, Vjuschkov refers A. annae as a nomen nudum,[22] when his description is quite viable.[15] Just like A. vladimiri, A. annae will be synonymized with I. latifrons by Tatarinov in 1974.[26]

In 2003, Mikhail F. Ivakhnenko erected a new genus of Russian gorgonopsian under the name of Leogorgon klimovensis, on the basis of a partial braincase and a large referred canine, both discovered in the Klimovo-1 locality, in the Vologda Oblast. In his official description, Ivakhnenko classifies this taxon among the subfamily Rubidgeinae, whose fossils are exclusively known from what is now Africa. This would therefore make Leogorgon the first known representative of this group to have lived outside this continent.[27] In 2008, however, Ivakhnenko noted that, due to its poorly known anatomy, Leogorgon could be a relative of the Russian Phthinosuchidae rather than the sole Russian representative of the Rubidgeinae.[17] In 2016, Kammerer formally rejected Ivakhnenko's classifications, because the holotype braincase of Leogorgon likely came from a dicynodont, while the attributed canine tooth is indistinguishable from that of Inostrancevia. Since then, Leogorgon has been recognized as a nomen dubium of which part of the fossils possibly come from Inostrancevia.[28]

Other species belonging to distinct lineages were sometimes inadvertently classified in the genus Inostrancevia. For example, in 1940, Efremov classifies a gorgonopsian of then-problematic status as I. progressus.[8] However, in 1955, Alexey Bystrow moved this species to the separate genus Sauroctonus.[29][30][8][16] A large maxilla discovered in Vladimir Oblast in the 1950s was also assigned to Inostrancevia, but the fossil would be reassigned to a large therocephalian in 1997, and later designated as the holotype of the genus Megawhaitsia in 2008.[31]

Description[edit]

Inostrancevia is a gorgonopsian with a fairly robust morphology, the Spanish paleontologist Mauricio Antón describing it as a "scaled-up version" of Lycaenops.[32] The numerous descriptions given to this taxon make it one of the most emblematic animals of the Permian period, mainly because of its large size among gorgonopsians, rivaled only by the South African genus Rubidgea,[16] the latter having a roughly similar size.[32] Gorgonopsians were skeletally robust, yet long-limbed for therapsids, with a somewhat dog-like stance, though with outwards-turned elbows.[32] It is unknown whether non-mammaliaform therapsids such as gorgonopsians were covered in hair or not.[33]

The specimens PIN 2005/1578 and PIN 1758, belonging to I. alexandri, are among the largest and most complete gorgonopsian fossils identified to date. Both specimens are around 3 m (9.8 ft) long,[32] with the skulls alone measuring over 50 cm (20 in).[3] However, I. latifrons, although known from more fragmentary fossils, is estimated to have a more imposing size, the skull being 60 cm (24 in) long, indicating that it would have measured 3.5 m (11 ft) and weighed 300 kg (660 lb).[34] The size of I. uralensis is unknown due to very incomplete fossils, but it appears to be smaller than I. latifrons.[8]

Skull[edit]

The overall shape of the skull of Inostrancevia is similar to those of other gorgonopsians,[3] although it has many differences allowing it to be distinguished from African representatives.[16] It has a broad back skull, a raised and elongated snout, relatively small eye sockets and thin cranial arches.[8][17][32] The pineal foramen is located near the posterior edge of the parietals and rests on a strong projection in the middle of an elongated hollow like impression.[3] The sagittal suture is reinforced with complex curvatures. The ventral surface of the palatine bones is completely smooth, lacking traces of palatine teeth or tubercles. Just like Viatkogorgon, the top margin of the quadrate is thickened.[17] The three recognized Russian species have notable characteristics between them: I. alexandri is distinguished by its relatively narrow occiput, a broad and rounded oval temporal fenestra and the transverse flangues of the pterygoid with teeth; I. latifrons is distinguished by a comparatively lower and broader snout, larger parietal region, fewer teeth and a less developed palatal tuberosities; and I. uralensis is characterized by a transversely elongated oval slot-like temporal fenestra.[8]

The jaws of Inostrancevia are powerfully developed, equipped with teeth able to hold and tear the skin of prey. The teeth are also devoid of cusps and can be distinguished into three types: the incisors, the canines and the postcanines.[b] All teeth are more or less laterally compressed and have finely serrated front and rear edges. When the mouth is closed, the upper canines move into position at the sides of the mandible, reaching its lower edge.[3] The canines of Inostrancevia measuring between 12 cm (4.7 in) and 15 cm (5.9 in), they are among the largest identified among non-mammalian therapsids,[17] only the anomodont Tiarajudens have similarly sized canines.[35] In the upper and lower jaws, these canines are roughly equal in size and are slightly curved.[17] The incisors turn out to be very robust. The postcanine teeth are present on the upper jaw, on its slightly upturned alveolar edges. In contrast, they are completely absent from the lower jaw. There are indications that the tooth replacement would have taken place by the young teeth, growing at the root of the old ones and gradually supplanting them.[3] The capsule of the canines is very large, containing up to three capsules of replacement canines at different stages of development.[17]

Postcranial skeleton[edit]

The skeleton of Inostrancevia is of very robust constitution, mainly at the level of the limbs.[15][36] The ungual phalanges have an acute triangular shape.[3][15][17] Inostrancevia has the most autapomorphic postcranial skeleton identified on a gorgonopsian. The scapula of this latter is unmistakable, with an enlarged plate-like blade unlike that of any other known gorgonopsians, but its anatomy is also unusual, with ridges and thickened tibiae, especially at their joint margins.[36] The scapular blade of Inostrancevia being extremely enlarged,[15][16][37] its morphology will most likely be subject to future study regarding its paleobiological function.[36]

Taxonomy[edit]

Classification[edit]

In the original description published in 1922, Inostrancevia was initially classified as a gorgonopsian close to the African genus Gorgonops.[3] Subsequently, few gorgonopsians will be listed in Russia, but the identification of Pravoslavlevia will mark a new turning point in its classification. In 1974, Tatarinov classified the two genera in the family Inostranceviidae.[38] In 1989, Denise Sigogneau-Russell proposes a similar classification, but moves the taxon reuniting the two genera as a subfamily, being renamed Inostranceviinae, and is classified in the more general family Gorgonopsidae.[37] In 2002, in his revision of the Russian gorgonopsians, Mikhail F. Ivakhnenko re-erects the family Inostranceviidae and classifies the taxon as one of the lineages of the superfamily "Rubidgeoidea", placed alongside the Rubidgeidae and Phtinosuchidae.[39] One year later, in 2003, he reclassifies Inostrancevia in the family Inostranceviidae, similar to Tatarinov's proposal, but the latter classifies it alone, making it a monotypic taxon.[27] In 2007, based on observations made on the occipital bones and canines, Eva V. I. Gebauer moved Inostrancevia as a sister taxon to the Rubidgeinae, a lineage consisting of robust African gorgonopsians.[40] In 2016 Christian F. Kammerer regarded Gebauer's analysis as "unsatisfactory", citing that many of the characters used by her analysis were based upon skull proportions that are variable within taxa, both individually and ontogenetically (i.e. traits that change through growth).[28]

In 2018, in their description of Nochnitsa, Kammerer and Vladimir Masyutin propose that all Russian and African taxa should be separately grouped into two distinct clades. For Russian genera (except basal taxa), this relationship is supported by notable cranial traits, such as the close contact between pterygoid and vomer. The discovery of other Russian gorgonopsians and the relationship between them and Inostrancevia has never before been recognized for the simple reason that some authors undoubtedly compared them to African genera.[16] The classification proposed by Kammerer and Masyutin will serve as the basis for all other subsequent phylogenetic studies of gorgonopsians.[23][24] As with previous classifications, Pravoslavlevia is still considered as the sister taxon of Inostrancevia.[16][23][24]

The following cladogram shows the position of Inostrancevia within the Gorgonopsia after Kammerer and Rubidge (2022):[24]

| Gorgonopsia |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Evolution[edit]

Gorgonopsians form a major group of carnivorous therapsids whose oldest-known representatives come from South Africa and appear in the fossil record from the Middle Permian. During this period, the majority of representatives of this clade were quite small and their ecosystems were mainly dominated by dinocephalians, large therapsids characterized by strong bone robustness.[41] Some genera, notably Phorcys, are relatively larger in size and already occupy the role of superpredator in certain geological formations of the Karoo Supergroup.[24] Gorgonopsians were the first group of predatory animals to develop saber teeth, long before true mammals and dinosaurs evolved. This feature later evolved independently multiple times in different predatory mammal groups, such as felids and thylacosmilids.[42] Geographically, gorgonopsians are mainly distributed in the present territories of Africa and European Russia,[16] with, however, an indeterminate specimen having been identified in the Turpan Depression, in north-west China,[43] as well as a possible fragmentary specimen discovered in the Kundaram Formation, located in central India.[44] After the Capitanian extinction, gorgonopsians began to occupy ecological niches abandoned by dinocephalians and large therocephalians, and adopted an increasingly imposing size, which very quickly gave them the role of superpredators. In Africa, it is mainly the rubidgeines who occupy this role,[28] while in Russia, only Inostrancevia acquires as such,[16][23][45] the rare gorgonopsians known and contemporary with the latter being smaller.[46][47]

Paleobiology[edit]

Hunting strategy[edit]

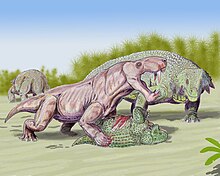

One of the most recognizable characteristics of Inostrancevia (and other gorgonopsians, as well) is the presence of long, saber-like canines on the upper and lower jaws. How these animals would have used this dentition is debated. The bite force of saber-toothed predators (like Inostrancevia), using three-dimensional analysis, was determined by Stephan Lautenschlager and colleagues in 2020:[48] their findings detailed that, despite morphological convergence among saber-toothed predators, there is a range of methods of possible killing techniques. The similarly-sized Rubidgea is capable of producing a bite force of 715 newtons; although lacking the necessary jaw strength to crush bone, the analysis found that even the most massive gorgonopsians possessed a more powerful bite than other saber-toothed predators.[49] The study also indicated that the jaw of Inostrancevia was capable of a massive gape, perhaps enabling it to deliver a lethal bite, and in a fashion similar to the hypothesised killing technique of Smilodon (or 'saber-toothed cat').[48]

Palaeoecology[edit]

European Russia[edit]

During the Late Permian when Inostrancevia lived, the Southern Urals (close in proximity to the Sokolki assemblage) were located around latitude 28–34°N and defined as a "cold desert" dominated by fluvial deposits.[50] The Salarevo Formation in particular (a horizon where Inostrancevia hails from) was deposited in a seasonal, semi-arid-to-arid area with multiple shallow water lakes which was periodically flooded.[51] The Paleoflora of much of European Russia at the time was dominated by a genus of peltaspermaceaen, Tatarina, and other related genera, followed by ginkgophytes and conifers. On the other hand, ferns were relatively rare and sphenophytes were only locally present.[50] There are also hygrophyte and halophyte plants in coastal areas as well as conifers that are more resistant to drought and higher altitudes.[52]

The fossil sites from which Inostrancevia was recorded contain abundant fossils of terrestrial and shallow freshwater organisms, including ostracods,[1] fishes, reptiliomorphs like Chroniosuchus and Kotlassia, the temnospondyl Dvinosaurus, the pareiasaur Scutosaurus, the dicynodont Vivaxosaurus and the cynodont Dvinia.[45][46][52][53] Inostrancevia was the top predator in its environment and could have preyed on the majority of the previously mentioned tetrapods.[11][45][46] Other smaller predators have existed alongside Inostrancevia, such as the smaller related gorgonopsian Pravoslavlevia and the therocephalian Annatherapsidus.[46][47]

South Africa[edit]

According to the fossil record, the Upper Daptocephalus Assemblage Zone, from which I. africana is known, would have been a well-drained floodplain. The area preceding just before the Permian–Triassic extinction, this would explain why there is no more diversification of animals than in the older strata of the Balfour Formation.[2][54]

As in the other formations of the Karoo Basin, dicynodonts are the most common animals in the Upper Daptocephalus Assemblage Zone. Among the most abundant dicynodonts are Daptocephalus (hence the name of the site), Diictodon and Lystrosaurus. Few genera of therocephalians are known within the site, only Moschorhinus and Theriognathus having been listed. The presence of the cynodont Procynosuchus is also reported.[55] The gorgonopsians Arctognathus and Cyonosaurus should be present based on their wide temporal distribution within the Karoo Basin, but formal fossils have not yet been discovered. As in the Russian fossil record, I. africana would have been the main predator in the area, most likely preying on contemporary dicynodonts.[2]

Extinction[edit]

Gorgonopsians, including Inostrancevia, disappeared in the Late Lopingian during the Permian–Triassic extinction event, mainly due to volcanic activities that originated in the Siberian Traps. The resulting eruption caused a significant climatic disruption unfavorable to their survival, leading to their extinction. Their ecological niches gave way to modern terrestrial ecosystems including sauropsids, mostly archosaurs, and among the few therapsids surviving the event, mammals.[56] However, some Russian gorgonopsians have already disappeared a little time before the event, having consequently abandoned some of their niches to large therocephalians.[31] Kammerer and his colleagues claimed that as the extinction of the rubidgeines in their respective territory of Africa, Inostrancevia migrated from Russia to take the role of apex predator within this place for a limited time. The presence of dicynodonts like Lystrosaurus would have been an opportunity for being a prey, as the latter thrived throughout the Permian–Triassic boundary.[2] However, an isolated left premaxilla of Inostrancevia from the Usili Formation in Tanzania during the earliest Lopingian age suggested otherwise, since the discovery of this specimen indicated that Inostrancevia already lived in Africa alongside other large rubidgeines such as Dinogorgon and Rubidgea before the latest Permian.[57]

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ The existence of these taxa are already mentioned in the article describing I. alexandri,[3] but were not officially named and described in detail until 1927.[15]

- ^ Previously identified as molars by Amalitsky,[3] this type of teeth was later redescribed as postcanine teeth, having a lack of functional range.[23]

References[edit]

- ^ a b Kukhtinov, D. A.; Lozovsky, V. R.; Afonin, S. A.; Voronkova, E. A. (2008). "Non-marine ostracods of the Permian-Triassic transition from sections of the East European platform". Bollettino della Società Geologica Italiana. 127 (3): 717–726.

- ^ a b c d e f g Kammerer, Christian F.; Viglietti, Pia A.; Butler, Elize; Botha, Jennifer (2022). "Rapid turnover of top predators in African terrestrial faunas around the Permian-Triassic mass extinction". Current Biology. 33 (11): 2283–2290. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2023.04.007. PMID 37220743. S2CID 258835757.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Amalitzky, V. (1922). "Diagnoses of the new forms of vertebrates and plants from the Upper Permian on North Dvina". Bulletin de l'Académie des Sciences de Russie. 16 (6): 329–340.

- ^ Benton et al. 2000, p. 4.

- ^ Gebauer 2007, p. 9.

- ^ Lankester 1905, p. 214-215.

- ^ Benton et al. 2000, p. 5.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Benton et al. 2000, pp. 93–94.

- ^ a b c "Inostrancevia". Paleofile.

- ^ Gebauer 2007, p. 229.

- ^ a b Lankester 1905, p. 221.

- ^ a b c Greenfield, Tyler (26 December 2023). "Who named Inostrancevia?". Incertae Sedis.

- ^ a b Hutchinson, Henry Neville (1910). "Anomalous Reptiles". Extinct Monsters and Creatures of Other Days: A Popular Account of Some of the Larger Forms of Ancient Animal Life. Museum of Comparative Zoology. London: Chapman & Hall. p. 105-124. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.40362. OCLC 1405542196. S2CID 191313118.

- ^ Jagt-Yazykova, Elena A.; Racki, Grzegorz (2017). "Vladimir P. Amalitsky and Dmitry N. Sobolev – late nineteenth/ early twentieth century pioneers of modern concepts of palaeobiogeography, biosphere evolution and mass extinctions". Episodes. 40 (3): 189–199. doi:10.18814/EPIIUGS/2017/V40I3/017022. S2CID 133685968.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Pravoslavlev, P. A. (1927). Gorgonopsidae from the North Dvina expedition of V. P. Amalitzki (in Russian). Vol. 3. Akademii Nauk SSSR. pp. 1–117.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Kammerer, Christian F. & Masyutin, Vladimir (2018). "Gorgonopsian therapsids (Nochnitsa gen. nov. and Viatkogorgon) from the Permian Kotelnich locality of Russia". PeerJ. 6: e4954. doi:10.7717/peerj.4954. PMC 5995105. PMID 29900078.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Ivakhnenko, Mikhail F. (2008). "Cranial morphology and evolution of Permian Dinomorpha (Eotherapsida) of eastern Europe". Paleontological Journal. 42 (9): 859–995. Bibcode:2008PalJ...42..859I. doi:10.1134/S0031030108090013. S2CID 85114195.

- ^ Tatarinov 1974, p. 96-99.

- ^ Tatarinov 1974, p. 99.

- ^ Botha-Brink, Jennifer; Huttenlocker, Adam K.; Modesto, Sean P. (2014), "Vertebrate Paleontology of Nooitgedacht 68: A Lystrosaurus maccaigi-rich Permo-Triassic Boundary Locality in South Africa" (PDF), in Kammerer, Christian F.; Angielczyk, Kenneth D.; Fröbisch, Jörg (eds.), Early Evolutionary History of the Synapsida, Vertebrate Paleobiology and Paleoanthropology, Springer Netherlands, pp. 289–304, doi:10.1007/978-94-007-6841-3_17, ISBN 978-94-007-6840-6, S2CID 82860920

- ^ Yefremov, Ivan (1940). "On the composition of the Severodvinian Permian Fauna from the excavation of V. P. Amalitzky". Academy of Sciences of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. 26: 893–896.

- ^ a b c d Vyushkov, Boris P. (1953). "On gorgonopsians from the Severodvinian Fauna". Doklady Akademii Nauk SSSR (in Russian). 91: 397–400.

- ^ a b c d e Bendel, Eva-Maria; Kammerer, Christian F.; Kardjilov, Nikolay; Fernandez, Vincent; Fröbisch, Jörg (2018). "Cranial anatomy of the gorgonopsian Cynariops robustus based on CT-reconstruction". PLOS ONE. 13 (11): e0207367. Bibcode:2018PLoSO..1307367B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0207367. PMC 6261584. PMID 30485338.

- ^ a b c d e Kammerer, Christian F.; Rubidge, Bruce S. (2022). "The earliest gorgonopsians from the Karoo Basin of South Africa". Journal of African Earth Sciences. 194: 104631. Bibcode:2022JAfES.19404631K. doi:10.1016/j.jafrearsci.2022.104631. S2CID 249977414.

- ^ Tatarinov 1974, p. 89.

- ^ a b Tatarinov 1974, p. 93.

- ^ a b Ivakhnenko, Mikhail F. (2003). "Eotherapsids from the East European placket (Late Permian)". Paleontological Journal. 37 (S4): 339–465.

- ^ a b c Kammerer, Christian F. (2016). "Systematics of the Rubidgeinae (Therapsida: Gorgonopsia)". PeerJ. 4: e1608. doi:10.7717/peerj.1608. ISSN 2167-8359. PMC 4730894. PMID 26823998.

- ^ Bystrow, A. P. (1955). "A gorgonopsian from the Upper Permian beds of the Volga". Voprosy Paleontologii. 2: 7–18.

- ^ Tatarinov 1974, p. 62.

- ^ a b Ivakhnenko, M. F. (2008). "The First Whaitsiid (Therocephalia, Theromorpha)". Paleontological Journal. 42 (4): 409–413. doi:10.1134/S0031030108040102. S2CID 140547244.

- ^ a b c d e Antón 2013, p. 79-81.

- ^ Benoit, Julien; Manger, Paul R.; Rubidge, Bruce S. (2016). "Palaeoneurological clues to the evolution of defining mammalian soft tissue traits". Scientific Reports. 6 (1): 25604. Bibcode:2016NatSR...625604B. doi:10.1038/srep25604. PMC 4860582. PMID 27157809.

- ^ Prothero, Donald R. (18 April 2022). "20. Synapsids: The Origin of Mammals". Vertebrate Evolution: From Origins to Dinosaurs and Beyond. Boca Raton: CRC Press. doi:10.1201/9781003128205-4. ISBN 978-0-36-747316-7. S2CID 246318785.

- ^ Cisneros, Juan Carlos; Abdala, Fernando; Rubidge, Bruce S.; Dentzien-Dias, Paula Camboim; de Oliveira Bueno, Ana (2011). "Dental occlusion in a 260-million-year-old therapsid with saber canines from the Permian of Brazil". Science. 331 (6024): 1603–1605. Bibcode:2011Sci...331.1603C. doi:10.1126/science.1200305. PMID 21436452. S2CID 8178585.

- ^ a b c Bendel, Eva-Maria; Kammerer, Christian F.; Smith, Roger M. H.; Fröbisch, Jörg (2023). "The postcranial anatomy of Gorgonops torvus (Synapsida, Gorgonopsia) from the late Permian of South Africa". PeerJ. 11: e15378. doi:10.7717/peerj.15378. PMC 10332358. PMID 37434869.

- ^ a b Sigogneau-Russell, Denise (1989). Wellnhofer, Peter (ed.). Theriodontia I: Phthinosuchia, Biarmosuchia, Eotitanosuchia, Gorgonopsia. Encyclopedia of Paleoherpetology. Vol. 17 B/I. Stuttgart: Gustav Fischer Verlag. ISBN 978-3437304873.

- ^ Tatarinov 1974, p. 82-83.

- ^ Ivakhnenko, Mikhail F. (2002). "Taxonomy of East European Gorgonopia (Therapsida)". Paleontological Journal. 36 (3): 283–292. ISSN 0031-0301.

- ^ Gebauer 2007, p. 232-232.

- ^ Day, Michael O.; Ramezani, Jahandar; Bowring, Samuel A.; Sadler, Peter M.; Erwin, Douglas H.; Abdala, Fernando; Rubidge, Bruce S. (2015). "When and how did the terrestrial mid-Permian mass extinction occur? Evidence from the tetrapod record of the Karoo Basin, South Africa". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 282 (1811): 20150834. doi:10.1098/rspb.2015.0834. PMC 4528552. PMID 26156768.

- ^ Antón 2013, p. 7-22.

- ^ Jun, Liu; Wan, Yiang (2022). "A gorgonopsian from the Wutonggou Formation (Changhsingian, Permian) of Turpan Basin, Xinjiang, China". Palaeoworld. 31 (3): 383–388. doi:10.1016/j.palwor.2022.04.004.

- ^ Ray, Sanghamitra; Bandyopadhyay, Saswati (2003). "Late Permian vertebrate community of the Pranhita–Godavari valley, India". Journal of Asian Earth Sciences. 21 (6): 643. Bibcode:2003JAESc..21..643R. doi:10.1016/S1367-9120(02)00050-0. S2CID 140601673.

- ^ a b c Tverdokhlebov, Valentin P.; Tverdokhlebova, Galina I.; Minikh, Alla V.; Surkov, Mikhail V.; Benton, Michael J. (2005). "Upper Permian vertebrates and their sedimentological context in the South Urals, Russia" (PDF). Earth-Science Reviews. 69 (1–2): 27–77. Bibcode:2005ESRv...69...27T. doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2004.07.003. S2CID 85512435.

- ^ a b c d Golubev, Valeriy K. (2000). "The faunal assemblages of Permian terrestrial vertebrates from Eastern Europe". Paleontological Journal. 34 (2): 211–224.

- ^ a b Benton et al. 2000, p. 93-109.

- ^ a b Lautenschlager, Stephan; Figueirido, Borja; Cashmore, Daniel D.; Bendel, Eva-Maria; Stubbs, Thomas L. (2020). "Morphological convergence obscures functional diversity in sabre-toothed carnivores". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 287 (1935): 1–10. doi:10.1098/rspb.2020.1818. ISSN 1471-2954. PMC 7542828. PMID 32993469.

- ^ Benoit, Julien; Browning, Claire; Norton, Luke A. (2021). "The First Healed Bite Mark and Embedded Tooth in the Snout of a Middle Permian Gorgonopsian (Synapsida: Therapsida)". Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution. 6: 699298. doi:10.3389/fevo.2021.699298. S2CID 235487002.

- ^ a b Bernardi, Massimo; Petti, Fabio Massimo; Kustatscher, Evelyn; Franz, Matthias; Hartkopf-Fröder, Christoph; Labandeira, Conrad C.; Wappler, Torsten; Van Konijnenburg-Van Cittert, Johanna H. A.; Peecook, Brandon R.; Angielczyk, Kenneth D. (2017). "Late Permian (Lopingian) terrestrial ecosystems: A global comparison with new data from the low-latitude Bletterbach Biota" (PDF). Earth-Science Reviews. 175: 18–43. Bibcode:2017ESRv..175...18B. doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2017.10.002. ISSN 0012-8252. S2CID 134260553.

- ^ Yakimenko, E. Yu.; Targul'yan, V. O.; Chumakov, N. M.; Arefev, M. P.; Inozemtsev, S. A. (2000). "Paleosols in Upper Permian sedimentary rocks, Sukhona River (Severnaya Dvina basin)". Lithology and Mineral Resources. 35 (2000): 331–344. Bibcode:2000LitMR..35..331Y. doi:10.1007/BF02782689. S2CID 140148404.

- ^ a b Yakimenko, Elena; Inozemtsev, Svyatoslav; Naugolnykh, Sergey (2004). "Upper Permian paleosols (Salarevskian Formation) in the central part of the Russian Platform: Paleoecology and paleoenvironment" (PDF). Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Geológicas. 21 (1): 110–119. S2CID 59417568..

- ^ Benton et al. 2000, pp. 113–114.

- ^ Viglietti, Pia A.; Smith, Roger M. H.; Rubidge, Bruce S. (2018). "Changing palaeoenvironments and tetrapod populations in the Daptocephalus Assemblage Zone (Karoo Basin, South Africa) indicate early onset of the Permo-Triassic mass extinction". Journal of African Earth Sciences. 138: 102–111. Bibcode:2018JAfES.138..102V. doi:10.1016/j.jafrearsci.2017.11.010. S2CID 134279628.

- ^ Viglietti, Pia A.; Smith, Roger M. H.; Angielczyk, Kenneth D.; Kammerer, Christian F.; Fröbisch, Jörg; Rubidge, Bruce S. (2016). "The Daptocephalus Assemblage Zone (Lopingian), South Africa: A proposed biostratigraphy based on a new compilation of stratigraphic ranges". Journal of African Earth Sciences. 113: 153–164. Bibcode:2016JAfES.113..153V. doi:10.1016/j.jafrearsci.2015.10.011. S2CID 128991282.

- ^ Benton, Michael J. (2018). "Hyperthermal-driven mass extinctions: killing models during the Permian–Triassic mass extinction". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A. 376 (2130). Bibcode:2018RSPTA.37670076B. doi:10.1098/rsta.2017.0076. PMC 6127390. PMID 30177561.

- ^ Brant, Anna J.; Sidor, Christian A. (2024). "Earliest evidence of Inostrancevia in the southern hemisphere: new data from the Usili Formation of Tanzania". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. e2313622. doi:10.1080/02724634.2024.2313622.

Bibliography[edit]

- Lankester, Edwin R. (1905). "The Pariasaurus and Inostransevia from the Trias of North Russia and South Africa". Extinct Animals. New York: Henry Holt & Company. pp. 190–245. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.13370. OCLC 5984379.

- Tatarinov, Leonid P. (1974). Териодонты СССР [Theriodonts of the USSR] (in Russian). Vol. 143. Trudy Paleontologicheskogo Instituta, Akademiya Nauk SSSR. pp. 1–226.

- Benton, Michael J.; Shishkin, Mikhail A.; Unwin, David M.; Kurochkin, Evgenii N. (2000). The age of dinosaurs in Russia and Mongolia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-55476-3.

- Gebauer, Eva V. I. (2007). Phylogeny and Evolution of the Gorgonopsia with a Special Reference to the Skull and Skeleton of GPIT/RE/7113 (PDF) (PhD). Eberhard-Karls University of Tübingen. Archived from the original on 22 July 2012.

- Antón, Mauricio (2013). Sabertooth. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-01042-1. OCLC 857070029.

External links[edit]

- Roman Uchytel. "Inostrancevia".