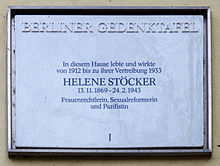

Helene Stöcker (13 November 1869 – 24 February 1943) was a German feminist, pacifist and gender activist.[1] She successfully campaigned to keep same sex relationships between women legal, but she was unsuccessful in her campaign to legalise abortion. She was a pacifist in Germany and joined the Deutsche Friedensgesellschaft.[2] As war emerged, she fled to Norway. As Norway was invaded, she moved to Japan and emigrated to America in 1942.

Life[edit]

Born in Wuppertal, Stöcker was raised in a Calvinist household and attended a school for girls which emphasised rationality and morality.[3] She moved to Berlin to continue her education and then she studied at the University of Bern, where she became one of the first German women to receive her doctorate. In 1905, she helped found the League for the Protection of Mothers (Bund für Mutterschutz, BfM),[1][4][5] and she became the editor of the organisation's magazine Mutterschutz (1905–1908) and then Die Neue Generation (1906–1932).[3]

In 1909, she joined Magnus Hirschfeld in successfully lobbying German parliament from including lesbian women in the law criminalising homosexuality.[6] Stöcker's influential new philosophy, called the New Ethic, advocated the equality of illegitimate children, legalisation of abortion, and sexual education, all in the service of creating deeper relationships between men and women which would eventually achieve women's political and social equality. This was received with dismay from more conservative women's organisations in Imperial Germany.[1]

During World War I and the Weimar period, Stöcker's interest shifted to activities in the peace movement. In 1921 in Bilthoven, together with Kees Boeke and Wilfred Wellock, she founded an organisation with the name Paco (the Esperanto word for "peace") and later known as War Resisters' International (Internationale der Kriegsdienstgegner, WRI). She was also very active in the Weimar sexual reform movement. The Bund für Mutterschutz sponsored a number of sexual health clinics, which employed both lay and medical personnel, where women and men could go for contraception, marriage advice, and sometimes abortions and sterilisation. From 1929 to 1932, she took one last stand for abortion rights. After a papal encyclical, the Casti connubii, issued on 31 December 1930 denounced sex without the intent to procreate,[7] the radical sexual reform movement collaborated with the Socialist and Communist parties to launch one final campaign against paragraph 218, which prohibited abortion. Stöcker added her iconic voice to a campaign that ultimately failed.

When the Nazis came to power in Germany, Stöcker fled first to Switzerland and then to England when the Nazis invaded Austria. Stöcker was attending a PEN writers conference in Sweden when war broke out and remained there until the Nazis invaded Norway, at which point she took the Trans-Siberian Railway to Japan and finally ended up in the United States in 1942. She moved into an apartment on Riverside Drive in NYC and died there of cancer in 1943.

Published works[edit]

Books[edit]

- 1906 – Die Liebe und die Frauen. Ein Manifest der Emanzipation von Frau und Mann im deutschen Kaiserreich.

- 1928 – Verkünder und Verwirklicher. Beiträge zum Gewaltproblem.

Papers[edit]

- Frauen-Rundschau, 1903–1922

- Mutterschutz, newspaper of the Bund für Mutterschutz, published from 1905 to 1907.

- Die Neue Generation, 1908–1932.

References[edit]

- ^ a b c Davies, Peter (2007), Fell, Alison S.; Sharp, Ingrid (eds.), "Transforming Utopia: The 'League for the Protection of Mothers and Sexual Reform' in the First World War", The Women's Movement in Wartime: International Perspectives, 1914–19, London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, pp. 211–226, doi:10.1057/9780230210790_13, ISBN 978-0-230-21079-0, retrieved 13 May 2021,

The most prominent personality in the German League was Helene Stöcker, a campaigner for sex reform and feminist causes, whose campaign for a new sexual ethics caused outrage in the conservative press, as well as consternation amongst the women's organisations of Imperial Germany.

- ^ Braker, Regina (2001). "Helene Stocker's Pacifism in the Weimar Republic: Between Ideal and Reality". Journal of Women's History. 13 (3): 70–97. doi:10.1353/jowh.2001.0059. ISSN 1527-2036. S2CID 143873641.

- ^ a b "Helene Stöcker (1869-1943)" (PDF). Museum für Verhütung und Schwangerschaftsabbruch - Museum of Contraception and Abortion. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 August 2019. Retrieved 12 November 2017.

- ^ "Helene Stöcker Papers (DG 035), Swarthmore College Peace Collection". www.swarthmore.edu. Archived from the original on 23 April 2019. Retrieved 12 November 2018.

- ^ Leng, Kirsten (2016). "Culture, Difference, and Sexual Progress in Turn-of-the-Century Europe: Cultural Othering and the German League for the Protection of Mothers and Sexual Reform, 1905–1914". Journal of the History of Sexuality. 25 (1): 62–82. doi:10.7560/JHS25103. ISSN 1043-4070. JSTOR 24616617. S2CID 146175792.

- ^ Mancini, E. (8 November 2010). Magnus Hirschfeld and the Quest for Sexual Freedom: A History of the First International Sexual Freedom Movement. Springer. p. 25. ISBN 978-0-230-11439-5.

- ^ "Casti connubii". vatican.va.

- Other sources

- Atina Grossmann: Reforming Sex: The German Movement for Birth Control and Abortion Reform, 1920–1950. Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1995. ISBN 0-19-512124-4

- Christl Wickert: Helene Stöcker 1869–1943. Frauenrechtlerin, Sexualreformerin und Pazifistin. Dietz Verlag, Bonn, 1991. ISBN 3-8012-0167-8

- Gudrun Hamelmann: Helene Stöcker, der 'Bund für Mutterschutz' und 'Die Neue Generation'. Haag Verlag, Frankfurt am Main, 1998. ISBN 3-89228-945-X

- Rolf von Bockel: Philosophin einer 'neuen Ethik': Helene Stöcker (1869–1943). 1991. ISBN 3-928770-47-0

- Annegret Stopczyk-Pfundstein: Philosophin der Liebe. Helene Stöcker. BoD Norderstedt, 2003. ISBN 3-8311-4212-2

Further reading[edit]

- Edward Ross Dickinson, Sex, Freedom, and Power in Imperial Germany, 1880–1914, Cambridge University Press, 2014. ISBN 1-1074-7119-2