HVO observation tower, abandoned in 2018 after structural damage | |

| Agency overview | |

|---|---|

| Formed | 1912 |

| Headquarters | Hilo, Hawaii, U.S. |

| Agency executive |

|

| Website | https://www.usgs.gov/observatories/hvo |

| Footnotes | |

| [1][2][3] | |

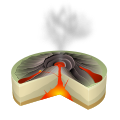

The Hawaiian Volcano Observatory (HVO) is an agency of the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) and one of five volcano observatories operating under the USGS Volcano Hazards Program. Based in Hilo, Hawaii, the observatory monitors six Hawaiian volcanoes: Kīlauea, Mauna Loa, Kamaʻehuakanaloa (formerly Lōʻihi), Hualālai, Mauna Kea, and Haleakalā, of which, Kīlauea and Mauna Loa are the most active. The observatory has a worldwide reputation as a leader in the study of active volcanism. Due to the relatively non-explosive nature of Kīlauea's volcanic eruptions for many years, scientists have generally been able to study ongoing eruptions in proximity without being in extreme danger.

Prior to May 2018, the observatory's offices were located at Uwekahuna Bluff, the highest point on the rim of Kīlauea Caldera. The summit collapse events during the 2018 eruption of Kīlauea damaged those facilities, so the observatory has since been operating from various temporary offices located in Hilo on the Island of Hawaiʻi.

History[edit]

Whitney Seismograph Vault No. 29 | |

| Nearest city | Volcano, Hawaii |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 19°25′12″N 155°17′17″W / 19.42000°N 155.28806°W |

| Area | 18 feet (5.5 m) by 17.5 feet (5.3 m) |

| Built | 1912 |

| NRHP reference No. | 74000292[4] |

| Added to NRHP | July 24, 1974 |

Besides the oral history of Ancient Hawaiians, several early explorers left records of observations. Rev. William Ellis kept a journal of his 1823 missionary tour,[5] and Titus Coan documented eruptions through 1881.[6] Scientists often debated the accuracy of these descriptions. When geologist Thomas Jaggar of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology gave a lecture in Honolulu in 1909, he was approached by businessman Lorrin A. Thurston (grandson of Asa Thurston who was on the 1823 missionary tour) about building a full-time scientific observatory at Kīlauea. The Hawaiian Volcano Research Association was formed by local businessmen for its support. George Lycurgus, who owned the Volcano House at the edge of the main caldera, proposed a site adjacent to his hotel and restaurant.

In 1911 and 1912, small cabins were built on the floor of the caldera next to the main active vent of Halemaʻumaʻu, but these were hard to maintain.[7] MIT added $25,000 in support in 1912 from the estate of Edward and Caroline Whitney to build a more permanent facility. The first instruments were housed in a cellar next to the Volcano House called the Whitney Laboratory of Seismology.[8] Inmates from a nearby prison camp had excavated through 5.5 feet (1.7 m) of volcanic ash. Massive reinforced concrete walls supported a small building built on top of the structure. Professor Fusakichi Omori of Japan, now best known for his study of aftershocks, designed the original seismometers. This seismograph vault (building number 29 on a site inventory) is state historic site 10–52–5506,[9] and was added to the National Register of Historic Places on July 24, 1974, as site 74000292.[10]

From 1912 until 1919, the observatory was run by Jaggar personally. Many important events were recorded, although as pioneers, the team often ran into major problems. For example, in 1913 an earthquake opened a crack in a wall and water seeped in. The windows meant to admit natural light caused the vault to heat up in the intense tropical sun.[7] The opening of the national park in 1916 (at the urging of Thurston) brought more visitors to bother the scientists, but also park rangers who would take over public lectures. The prison that had supplied laborers was replaced by the Kīlauea Military Camp.[11]

In 1919, Jaggar convinced the National Weather Service to take over operations at the observatory. In 1924, the observatory was taken over by the United States Geological Survey and it has been run by the USGS ever since (except for a brief period during the Great Depression, when the observatory was run by the National Park Service).[12] When the Volcano House hotel burned to the ground in 1940, the old building was torn down (although the instruments in the vault continued to be used until 1961).

George Lycurgus convinced friends in Washington D.C. (many of whom had stayed in the Volcano House) to build a larger building farther back from the cliff, so he could build a new larger hotel at the former HVO site. By 1942, the "Volcano Observatory and Naturalist Building" was designated number 41 on the park inventory. However, with the advent of World War II, it was commandeered as a military headquarters. HVO was allowed to use building 41 from October 1942 to September 1948, when it became the park headquarters (and still is today, after several additions).[7]

About two miles west, in an area known as Uwekahuna, a "National Park Museum and Lecture Hall" had been built in 1927. The name means roughly "the priest wept" in the Hawaiian Language, which indicates it might have been used to make offerings in the past.[13] The HVO moved there in 1948 after some remodeling of the building. This site was even closer to the main vent of Kīlauea. In 1985 a larger building was built for the observatory adjacent to the old lecture hall, which was turned back into a museum and public viewing site. In the mid-1980s, HVO launched the Big Island Map Project (BIMP) to update the geologic map of the island of Hawai'i. Its major publication is the 1996 Geologic Map of the Island of Hawai'i (1996) by E.W. Wolfe and Jean Morris, digitized in 2005.[14][15]

Leadership[edit]

The Scientist-in-Charge has 3 main duties: manage funding and equipment availability to ensue smooth operation; direct staff on how to monitor and respond to volcanic events; and engage in outreach to the public.[16]

- HVO Directors

- 1912 to 1940, Thomas A. Jaggar[17]

- 1940 to 1951, Ruy Finch[17]

- 1951 to 1955, Gordon A. Macdonald[17]

- 1956 to 1958, Jerry P. Eaton[17]

- HVO Scientists-in-Charge

- 1958 to 1960, Kiguma Jack Murata[17]

- 1960 to 1961, Jerry P. Eaton[17]

- 1961 to 1962, Donald H. Richter[17]

- 1962 to 1963, James G. Moore[17]

- 1964 to 1970, Howard A. Powers[17]

- 1970 to 1975, Donald W. Peterson[17]

- 1975 to 1976, Robert I. Tilling[17]

- 1976 to 1978, Gordon P. Eaton[17]

- 1978 to 1979, Donald W. Peterson[17]

- 1979 to 1984, Robert W. Decker[17]

- 1984 to 1991, Thomas L. Wright[17]

- 1991 to 1996, David A. Clague[17]

- 1996 to 1997, Margaret T. Mangan[17]

- 1997 to 2004, Donald A. Swanson[17]

- 2004 to 2015, James P. Kauahikaua[18]

- 2015 to 2020, Tina Neal[18]

- 2021 to present, Ken Hon

Operations[edit]

The Hawaiian Volcano Observatory hosts a large monitoring network, with over 100 remote stations transmitting data 24 hours a day.[19][20] This information is provided immediately over the Internet, as is live coverage of ongoing eruptions from several webcams accessible from the Hawaiian Volcano Observatory website (see External links). Another important function of HVO is to monitor the sulphur emissions that produce the volcanic pollution condition known as vog. The observatory advises the park service when to close areas due to this and other volcanic hazards.[21]

While the main Observatory building itself was not open to the public, the adjacent Thomas A. Jaggar Museum included interpretive exhibits on the work performed at the observatory. The exhibits ranged from general information on volcanoes and lava to the scientific equipment and clothing used by volcanologists. Some of the museum's windows provided a sheltered view of Halemaʻumaʻu and the Kīlauea Caldera. A public observation deck at the museum, overlooking Kīlauea and formerly open 24 hours a day, provided views of the area.[22]

On May 10, 2018, Hawaii Volcanoes National Park was closed to the public in the Kīlauea volcano summit area, including the visitor center and park headquarters, due to explosions, earthquakes and toxic ash clouds from Halemaʻumaʻu. While much of the park was reopened on September 22, 2018, the former Observatory building and Jaggar Museum remain closed, due to considerable structural damage done to the facility.[23]

With nearly 70 million in federal relief dollars appropriated in 2019, the Observatory is currently looking for a new location for their operations.[24] In April 2019, Hawaii Public Radio reported that a move of the observatory staff to Oʻahu was being considered.[25] In August 2019 it was reported that the Observatory was looking for a new permanent site in Hilo to replace the transitional offices in use since 2018.[26][27]

References[edit]

- ^ Hawaiian Volcano Observatory, About the Hawaiian Volcano Observatory Retrieved Jan. 19, 2023.

- ^ "New Scientist-in-Charge at the USGS Hawaiian Volcano Observatory - HS Today". February 3, 2021. Retrieved April 7, 2023.

- ^ Staff (February 3, 2021). "Ken Hon named scientist-in-charge at Hawaiian Volcano Observatory – UH Hilo Stories". Retrieved April 7, 2023.

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. March 13, 2009.

- ^ William Ellis (1825). A journal of a tour around Hawaii, the largest of the Sandwich Islands. Crocker and Brewster, New York, republished 2004, Mutual Publishing, Honolulu. p. 282. ISBN 1-56647-605-4.

- ^ Coan, Titus (1882). Life in Hawaii. New York: Anson Randolph & Company. ISBN 0-8370-6036-2.

- ^ a b c "Buildings and Facilities". United States Geological Survey. Retrieved June 24, 2009.

- ^ Russell A. Apple. "HVO History". United States Geological Survey HVO web site. Retrieved July 11, 2009.

- ^ Historic Places in Hawaii County on official state web site

- ^ Russell A. Apple (1972). "Whitney Seismograph Vault #29 nomination form". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- ^ "About KMC". Kīlauea Military Camp. Archived from the original on April 23, 2009. Retrieved June 25, 2009.

- ^ "Thomas Jaggar, HVO's founder". Hawaiian Volcano Observatory's Volcano Watch. March 21, 1997. Retrieved June 21, 2009.

- ^ "Lookup of "Uwekahuna"". on Hawaiian Place Names web site. Retrieved June 25, 2009.

- ^ Wolfe (compiler), E. W.; Morris, Jean (1996). "Geologic map of the Island of Hawaii". doi:10.3133/i2524A.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Poland, Michael P.; Takahashi, T. Jane; Landowski, Claire M., eds. (2014). "Characteristics of Hawaiian volcanoes". Reston, VA: 442. doi:10.3133/pp1801.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Volcano Watch — HVO people and jobs, Part 2: Who and what is the Scientist-in-Charge? | U.S. Geological Survey". www.usgs.gov. Retrieved May 28, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Babb, Janet L.; Kauahikaua, James P.; Tilling, Robert I. (2011). "The story of the Hawaiian Volcano Observatory—A remarkable first 100 years of tracking eruptions and earthquakes". U.S. Geological Survey General Information Product 135. General Information Product: i-63. doi:10.3133/gip135.

- ^ a b "Volcano Watch — Ken Hon returns to HVO as Scientist-in-Charge". U.S. Geological Survey.

- ^ "Earthquakes in Hawaii". USGS Hawaiian Volcano Observatory Network. Retrieved June 25, 2009.

- ^ "About the Hawaiian Volcano Observatory | U.S. Geological Survey".

- ^ "Closed Areas and Advisories". National Park Service Hawaii Volcanoes National Park web site.

- ^ "Jaggar Museum". National Park Service web site. Retrieved June 21, 2009.

- ^ "Hawaii Island isn't itself anymore. Lava and quakes have transformed it in interesting ways". Los Angeles Times. January 6, 2019. Retrieved December 7, 2021.

- ^ Burnett, John (August 25, 2019). "HVO settles in: Site selection, facility design could take years". Hawaii Tribune-Herald. Retrieved December 7, 2021.

- ^ "Hawai'i County Officials Unaware Feds Considering Off-Island Move for Volcano Observatory". Hawai'i Public Radio. April 1, 2019. Retrieved December 7, 2021.

- ^ "Hawaii Volcano Observatory begins searching for new site". Hawaii News Now. August 28, 2019. Retrieved December 7, 2021.

- ^ "Building a New Hawaiian Volcano Observatory". www.usgs.gov. Retrieved December 7, 2021.

Further reading[edit]

- Decker, Robert W.; Wright, Thomas L.; Stauffer, Peter H., eds. (1987). "Volcanism in Hawaii: Papers to Commemorate the 75th Anniversary of the Founding of the Hawaiian Volcano Observatory". U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 1350. doi:10.3133/pp1350.

- Babb, Janet L.; Kauahikaua, James P.; Tilling, Robert I. (2011). "The Story of the Hawaiian Volcano Observatory—A Remarkable First 100 Years of Tracking Eruptions and Earthquakes". U.S. Geological Survey General Information Product 135. General Information Product: i-63. doi:10.3133/gip135.

- Poland, Michael P.; Takahashi, T. Jane; Landowski, Claire M., eds. (2014). "Characteristics of Hawaiian Volcanoes". U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 1801. doi:10.3133/pp1801.

External links[edit]

- Hawaiian Volcano Observatory official web site

- Current SO2 conditions Archived 2012-02-26 at the Wayback Machine from Hawaii Volcanoes National Park

- Live web cams from HVO of Halemaʻumaʻu and Puʻu Ōʻō vents, and other locations