| |

| Agency overview | |

|---|---|

| Formed | December 1918 |

| Preceding agency |

|

| Dissolved | September 1983 |

| Superseding agency |

|

| Jurisdiction | Government of Victoria |

The Forests Commission Victoria (FCV) was the main government authority responsible for management and protection of State forests in Victoria, Australia between 1918 and 1983.

The Commission was responsible for ″forest policy, prevention and suppression of bushfires, issuing leases and licences, planting and thinning of forests, the development of plantations, reforestation, nurseries, forestry education, the development of commercial timber harvesting and marketing of produce, building and maintaining forest roads, provision of recreation facilities, protection of water, soils and wildlife, forest research and making recommendations on the acquisition or alienation of land for forest purposes″.[1]

The Forests Commission had a long and proud history of innovation and of managing Victoria's State forests but in September 1983 lost its discrete identity when it was merged into the newly formed Victorian Department of Conservation, Forests and Lands (CFL) along with the Crown Lands and Survey Department, National Park Service, Soil Conservation Authority and Fisheries and Wildlife Service.[2]

After the amalgamation the management of State forests and the forestry profession continued but the tempo of change accelerated, with many more departmental restructures occurring over the subsequent three decades. Responsibilities are currently split between the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning (DELWP),[3] Parks Victoria, Melbourne Water, Alpine Resorts Commission, the State Government-owned commercial entity VicForests[4] and the privately owned Hancock Victorian Plantations (HVP).[5]

Late 1800s – Chaos in the forest[edit]

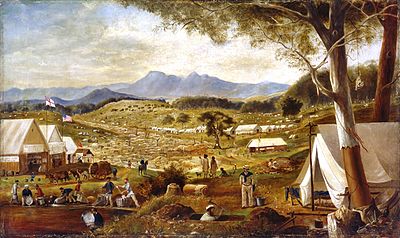

Before European settlement in the early 1800s, around 88% of the 23.7 million hectare colony of what was to become the State of Victoria in 1851 was tree covered.[6] However, the Victorian gold rush of the 1850s combined with widespread and indiscriminate land clearing for mining, agriculture and settlement became one of the major causes of forest loss and degradation.[7][8] This caused alarm amongst early foresters and the wider community.[9]

Forest management in the late 1800s was chaotic. As early as 1865, the Argus Newspaper took up the cause of ‘protecting our forests’ arguing the substantial benefits of timber production, avoiding the wasting of soil, conserving natural streams, avoiding adverse climate impacts and beneficially distributing storm runoff.[10]

Later on 16 September 1869, the first "Overseer of Forests and Crown Land Bailiff", William Ferguson was appointed. The second progress report of a Royal Commission on Foreign Industries and Forests in 1872, included a recommendation for the establishment of a State nursery near Macedon railway station "with the object of raising useful timber trees for distribution to selectors, and for the planting of reserves denuded of indigenous timber". Ferguson then established the first State Nursery at Macedon in 1872.[11]

By 1871 the Australian Natives Association (ANA) was formed and joined the campaign and were active on forest conservation for a prolonged period. The Field Naturalists Club of Victoria (FNCV) became involved in 1881.

It is surprising and perhaps ironic that organised mining interests, including influential mining parliamentarians, were the early public advocates for forest protection, taking up the cause in the 1860s. Their advocacy was based more on the profitability of their mining interests than forest conservation. The miners selfishly wanted well-regulated state forest reserves to ensure a plentiful future supply of mining timbers at reasonable prices.[9][7]

In 1871, local Forest Boards attempted to exercise some control, however the task of regulating wasteful clearing proved formidable and they were abolished in 1876. By 1873 it was estimated that were some 1150 steam engines in the gold mining industry, devouring over one million tons of firewood.[11]

In October 1882, the pioneering forester John la Gerche was appointed as one of sixteen Crown Lands Bailiffs and Foresters within the Agriculture Branch of the Department of Lands. Their appointment held out a promise to end the forest destruction under the 1884 Land Act which recognised the significance of forests for public purposes but the budget allocation was a paltry £4000. La Gerche established a nursery at Sawpit Gully in 1887 near what is now the Victorian School of Forestry at Creswick. He went onto become one of the founding Inspectors in the new State Forest Department in 1907.[11]

Inquiries, indecision and inertia[edit]

At the urging of the Governor of Victoria, Lord Henry Brougham Loch, who had served in Bengal cavalry and maintained an interest in forests, and had seen there the results of forest management under the great European foresters Brandis, Schlich and Ribbentrop, the Government invited Conservator Frederick D'A. Vincent from the Imperial Forest Service in India to visit in 1887 and make recommendations. But to seek advice was one thing; to take it was another, and while Vincent's scathing report was available to subsequent inquiries and was eventually tabled in the House in 1895, it was "so frank and outspoken that it has never been published".[9]

I am very unfavourably impressed with the state of the forests .... I am surprised that some effectual measures have not been taken to prevent further waste .... present arrangements are quite puerile and so ill-conceived that they can scarcely be discussed

- — Conservator, Frederick D'A Vincent, Imperial Forest Service, 1887.

Later on 14 June 1888, the first Conservator of Forests, George Samuel Perrin[12] was appointed. He had previous experience in South Australia and Tasmania and despite having little power or authority, was able to appoint a number of foresters over the next 12 years.[11] He produced a report containing a number illustrations to Parliament on 30 June 1890.[13] This visionary report clearly identified the issues and set out reforms to ensure Victoria would have a healthy, diverse and extensive forest estate 130 years later.[10] Perrin was also acquainted with the Government botanist Ferdinand Von Mueller who named, Eucalyptus perriniana after him.

Meanwhile, the gold rush was petering out and Melbourne's land boom[14] of the 1880s was inevitably followed by a financial crash in 1891, which combined with the Federation Drought from 1895 to 1902, depressed economic conditions for a decade or more. Not surprisingly, the Colonial Government had little appetite for changing the status-quo and introducing restrictive forest legislation.[15]

Matters had come to a head previously on Black Wednesday (9 January 1878) when the State Government sacked over 300 senior public servants and judges suddenly overnight without warning. The sackings were in part directed at the desire of the Premier, Graham Berry, to penalise those in the public service who backed the intransigence of the Legislative Council which was dominated by pastoral and grazing interests and which had resisted land reform. Berry's election manifesto proposed a punitive land tax designed to break up the squatter class's great pastoral properties – about 800 men at this time owned most of Victoria's grazing lands.

But separately, in a bold and visionary political move, the management of 157,000 hectares of Melbourne's forested water catchments of the Upper Yarra were vested in the Melbourne and Metropolitan Board of Works (MMBW) in 1891 but with a controversial closed catchment policy where timber harvesting and public access was not permitted.[11]

Perhaps exemplifying the influence of Indian forestry throughout the British Empire, in 1895 the Commissioner of Crown Lands and Survey, Sir Robert Wallace Best, invited Inspector-General Berthold Ribbentrop, from the Imperial Forest Service. His report[16] prompted yet another Royal Commission which commenced in 1897 and produced 14 separate reports before closing in 1901.[15]

"State forest conservancy and management are in an extraordinary backward state" .... Inspector-General Berthold Ribbentrop, Imperial Forest Service – 1896.

Departmental restructuring and uncertainty is not new. Between 1856 and 1907 the responsibility for administration of Victoria's forest estate shunted back and forth at least eleven times between three Government Departments including Lands and Survey, Agriculture and Mines.[1][2]

1900s – Royal Commission findings[edit]

In 1900 State forests were still commonly regarded by the general public, and by most of their parliamentary representatives, as the inexhaustible "wastelands of the Crown" and ready for disposal via alienation into freehold property for the purposes of agricultural settlement.[7]

For nearly 50 years there had been Government inquiries, three independent reports from D'A. Vincent (1887), Perrin (1890), Ribbentrop (1895), the Royal Commission (1897–1901) together with impassioned speeches and separate pieces of legislation calling for the conservation of the states forests which had all been brought unsuccessfully before the Victorian Parliament.[15] It was not until the former British colonies combined in 1901 to become the states of a Federal Australia that a Victorian Forest Bill was finally passed.

State Forests Department – 1907[edit]

Despite spirited opposition by agricultural and grazing interests the Forest Act (1907) No. 2095 finally constituted the State Forest Department (SFD) which came into effect on 1 January 1908, formally setting aside timber reserves and providing for rehabilitation after mining and logging. The first Conservator of Forests was Hugh Robert Mackay who had been both a Senior Inspector and Secretary to the Royal Commission of 1897–1901 while the first Minister was Donald McLeod and the first Secretary was William Dickson, who was also Secretary for Mines.

The creation of the State Forest Department represented the most significant institutional development in Victoria's history of forest management to that point. The fledgling department had 66 staff on 31 December 1900 including, 1 Conservator, 1 Chief Inspector, 1 Inspector, 23 Foresters and 40 Forest Foremen but foreshadowed that it expected to increase over the years to come.[11] Nonetheless, the challenges facing the new organisation were formidable, including protecting ecosystems about which little was scientifically understood, and responsibility for vast areas of rugged, remote country about which little was known.[9]

The next ten years saw a steady expansion in staff numbers, promulgation of controlling regulations, increased production from the forest, thinning and fire protection works such as fire break construction, together with rehabilitation of the native forest which had suffered from indiscriminate cutting.[17]

However, frustrated at the lack of progress in forestry and broader forest conservation, several foresters and scientists formed the Australian Forest League (AFL) in 1912 which stayed active for the next 34 years. The inaugural President was notable botanist, Professor Alfred James Ewart from Melbourne University, who oversaw the curriculum at the Victorian School of Forestry. They received valued support from Governor-General Sir Ronald Munro-Ferguson during the war years over political interference in forest management, securing adequate funding, reducing waste, expanding softwood plantations and addressing growing international concern at impending timber shortages.[7]

Forestry training – 1910[edit]

The new Forest Act (1907) also recognised that effective management of forests required appropriately skilled staff, stipulating that no person could be appointed to a forestry position without completing a relevant course and passing a special examination, thus paving the way for the establishment of a forestry school.[9] The Victorian School of Forestry (VSF) at Creswick was established in 1910 and was located at the old hospital which had been built in 1863 during the gold rush. The creation of VSF was one of the many recommendations of the 1901 Royal Commission and the school became the first of its kind in Australia.[18]

Forests Commission Victoria - 1918[edit]

In December 1918, a comprehensive amendment to the Forests Act created the Forests Commission Victoria (FCV) with three Commissioners to lead a new independent organisation. The new Commission first met on 1 October 1919 and the chairman was a young Welsh Forester, Owen Jones[19] while the first Minister was William Hutchinson. The key principals of the 1918 Act are thought to have been derived from the earlier 1907 legislation and include:

- conservation, development and utilisation of the indigenous forests, based on sound forestry principals;

- establishment of adequate exotic softwoods plantations;

- prosecution of essential research work concerning the natural products of the forests; and

- the need for an effective fire prevention and fire suppression organisation.

Significantly, the new legislation provided for the establishment of a Forestry Fund so the Commission could raise its own revenue from timber sales and enter into loans and therefore give it some capacity to implement its own policies and programs. Revenue from timber royalties and other sources grew five-fold within the first five years. The Commission was also authorised to recruit, employ and manage its own staff.[17]

Areas permanently reserved as State Forest[edit]

Prior to the 1918 legislation, forest areas were reserved by the Minister of Lands and Agriculture who was also responsible for alienating Crown Land for farming and towns. There were obvious conflicts in administering these competing responsibilities. As a result, permanent forest reservation was slow and limited for the period of Victoria's first seven decades. Reservations had been made in 1862, 1873, 1898 and 1903 and the Conservator of Forests, George Perrin, reported the total forested area in 1888 was 4.8 million ha most of which was inaccessible. Only a small proportion was permanently reserved, and some was in Melbourne water supply catchments closed to harvesting and visitors.[13]

1920s – Formative years[edit]

Twenty Forests Commission employees are known to have enlisted in the Great War[22] including the famous hero at both Gallipoli and the Western Front – Albert Jacka, VC.

Servicemen returning from the First World War renewed pressure on forest clearing with the expansion of various soldier settlement schemes.[23] Between 1903 and 1928 the Crown estate was significantly reduced down to about one third of the State or 8.6 million hectares.

Forest types[edit]

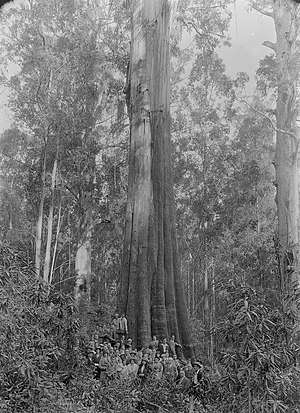

Victoria is blessed with a wide diversity of native forest, dominated by eucalyptus (often known as gum trees). These forests contain many diverse habitats and include those found in the cool, mountainous, high rainfall areas in the east of the state, and in the Otways and Strzelecki Ranges near the coast. These wet forests are dominated by stands of alpine ash, messmate, shining gum and mountain ash (the tallest hardwood tree in the world). They remain the major source of high-quality seasoning timber for furniture, flooring, joinery and pulpwood. The dryer foothill forests contain mixtures of messmate and other commercial species, whereas the Murray River has extensive stands of durable red gum along its banks.[24] Large tracts of mallee desert and box-ironbark woodlands are found in the drier northwest.

Tall trees[edit]

Tree height is influenced by species, genetics, age, stand density, soil type and depth, rainfall, aspect, altitude, protection from wind and snow damage, fire history and insect attack.[25] Scientists believe that trees have a theoretical maximum height of 130 m (430 ft),[26] even though there are many historical accounts of taller trees. The main physiological factor limiting tree height is its ability to suck a continuous column of water up against the forces of gravity. The crowns of the tallest trees need to lift sap more than 10 times the surrounding atmospheric pressure by combining the complex physics of capillary action and leaf transpiration of the water pathway known as the Soil Plant Atmosphere Continuum. Contrary to popular belief, tree roots do not pump water.[27]

There had long been recognition of the conservation and aesthetic values of Victoria's large forest trees.[28] As early as 1866 Baron Ferdinand Von Mueller, the Government botanist published some astonishing, and probably exaggerated claims of a mountain ash (Eucalyptus regnans – monarch of the eucalypts) on the Black's Spur near Healesville being 480 feet high. There were reports from nurseryman David Boyle[29] and others of trees in the Yarra Valley, Otways and Dandenong Ranges reaching "half a thousand feet".[30] Doyle was later savagely criticised by Melbourne newspapers in 1889 about a tree he had named "The Baron" in homage to his friend von Mueller. The tree was growing at Sassafras Gully in the Dandenong Ranges and Doyle had initially measured it in 1879 at 522 feet tall. It was later remeasured for the Melbourne exhibition in 1888 where it had reduced in size to 466 feet. However, when properly measured by Commissioner Perrin and surveyor Mr Fuller from the Water Supply Dept in 1889, it was found to be only 219 feet 9 inches.[31] Its girth had also shrunk from 114 feet to 48 feet. Poor measurement techniques in thick scrub may partly explain the anomalies.[29]

In 1982, Ken Simpendorfer, a senior officer with the Forests Commission undertook a search of official Victorian archives. He unearthed a forgotten report from more than a century ago and a claim by William Ferguson, the State Government's first "Overseer of Forests and Crown Land Bailiff" who was appointed in 1869. In a letter written in the Melbourne Age newspaper from Ferguson to the Assistant Commissioner of Crown Lands, Clement Hodgkinson, dated 22 February 1872 he reported trees in great number and exceptional size in the Watts River catchment but his account is often disputed as unreliable.[11][32][33]

"Some places, where the trees are fewer and at a lower altitude, the timber is much larger in diameter, averaging from 6 to 10 feet and frequently trees to 15 feet in diameter are met with on alluvial flats near the river. These trees average about ten per acre: their size, sometimes, is enormous. Many of the trees that have fallen by decay and by bush fires measure 350 feet in length, with girth in proportion. In one instance I measured with the tape line one huge specimen that lay prostrate across a tributary of the Watts and found it to be 435 feet from the roots to the top of its trunk. At 5 feet from the ground it measures 18 feet in diameter. At the extreme end where it has broken in its fall, it (the trunk) is 3 feet in diameter. This tree has been much burnt by fire, and I fully believe that before it fell it must have been more than 500 feet high. As it now lies it forms a complete bridge across a narrow ravine" .... William Ferguson, The Melbourne Age, February 1872. [33]

In 1976, a monument was unveiled by the Hon Jim Balfour to the "World's Tallest Tree" near Thorpdale which in 1884 was measured by a surveyor, George Cornthwaite at 375 feet after it had been chopped down.[11][30] This account was reported in the Victorian Field Naturalist many years later in July 1918 and is often considered the most reliable record of Victoria's tallest tree.[34][35]

The public remained fascinated by large trees and to celebrate the Melbourne Centennial Exhibition in 1888 offered a reward for the tallest tree. Parliamentarian and exhibition organiser, James Munro personally offered an additional £100 for anyone who could locate a tree taller than 400 feet. No such tree was ever found.[11] The tallest tree reliably measured for the exhibition was the "New Turkey Tree" reported to be near Mt Baw Baw (but probably closer to Noojee on the New Turkey Spur which is not far from the Ada Tree) at 326 feet 1 inch with a girth of 25 feet and 7 inches.

Around the turn of the century, Nicholas John Caire[36] named and photographed many on Victoria's remaining giant trees including King Edward VII at Marysville. Some of his photos were displayed in Victorian Railways carriages and made into postcards.[37] However, by this time most of largest and straightest trees had already been removed by timber splitters.[11]

A more authoritative list "Giant Trees of Victoria" was later compiled by Mr A. D. Hardy from the State Forest Department in 1911 identifying numerous trees over 300 feet at Fernshaw and Narbethong with similar heights recorded in the Otways and Baw Baw Ranges.[11]

In 1929, the Forests Commission set aside a "sample acre" within the Cumberland Scenic Reserve near Marysville. The site only narrowly escaped the 1939 Black Friday bushfires but unfortunately 13 of its big trees were destroyed during a storm later in 1959.[30] The tallest tree on the plot was reduced from 301.5 feet to about 276 feet after a large part of its crown was damaged. Another major storm on 21 December 1973 reduced it further to 267 feet.[25]

The Chairman of the Forests Commission, Alfred Vernon Galbraith studied mountain ash for his Diploma of Forestry (Vic)[38] and wrote in 1937 that "they can make serious claims to be the world's highest tree". His successor, Finton Gerraty personally measured a fallen tree near Noojee after the 1939 bushfires at 338 feet and with "its top tantalisingly broken off".[30][39]

The Mueller Tree[35] grew on Mount Monda north of Healesville, measured 307 feet, and was made famous after a visit in 1895 by a party including Baron Von Muller, Mr A. D. Hardy, from the State Forests and Nurseries Branch, members of the Geographical Society accompanied by renowned photographer John William Lindt[40] who also was the owner of "The Hermitage" guesthouse on the Black's Spur. The tree was then "rediscovered" and renamed by Mr Harold Furmston,[41] an employee of the Melbourne and Metropolitan Board of Works in the 1930s.[42] It was remeasured once again by Mr A. D. Hardy in 1933 who proclaimed it to be still in good health, 62 feet in circumference at a height of five feet above the ground and at 10 feet up its circumference was still 50 feet. He estimated its height to be 287 feet (20 feet shorter than his earlier 1895 measurements).[43][11] There was some debate from the Healesville Tourism Association[44] during this period about its name but either way the Mueller – Furmston Tree was a popular destination inside the Melbourne Water closed catchments until it collapsed in about 2000.[45]

Recent measurements between 2000 and 2002 of over 200 of Victoria's trees found the tallest specimen of mountain ash was inside Melbourne Water's Wallaby Creek Catchment at Kinglake being over 300 years old and 301 feet (92 m) high.[25] The height was accurately determined using a ground-based laser rangefinder and then verified by a tree climber with a tapeline, however it later perished along with 15 other tall trees during the 2009 Black Saturday bushfires.

Modern Lidar imagery of the forests is being used to find remaining stands of tall trees. The tallest regrowth mountain ash in Victoria is currently named Artemis[46] which can be found near Beenak at 302 feet (92 m) while the Ada Tree at 236 feet (72 m) is thought to be between 350 and 450 years old,[25] but with a senescent crown and is a popular tourist destination in State forest east of Powelltown. Australia's the tallest measured living specimen of mountain ash, named Centurion, stands 100.5 metres (330 feet) tall in Tasmania.[47][48]

Whether a mountain ash over 400 feet high ever existed in Victoria is now almost impossible to substantiate but the early accounts from the 1860s are still quoted in contemporary texts such as the Guinness Book of Records and Carder,[49] as well as being widely restated on the internet.

Currently the world's tallest living tree is a Sequoia sempervirens, named the Hyperion, discovered in California in 2006. It is believed to be between 700 and 800 years old and was measured at 380.3 feet.

Early silviculture[edit]

Silviculture is defined as the art and science of controlling the establishment, health, growth, quality, protection and use of forests. It can involve a range of treatments such as planting, seeding, thinning, together with a wide range of harvesting techniques such as clear-felling through to single tree selection. Much of the early silvicultural knowledge was unsuccessfully translated from Europe so in response to some difficulties achieving satisfactory regrowth after harvesting the Commission pioneered much of the early scientific research into the biology of the eucalypts and developed many innovative operational techniques for high intensity slash burning, aerial seeding, planting, thinning and tending. This commitment to silvicultural research continued throughout the life of the Commission.[11]

Steam era[edit]

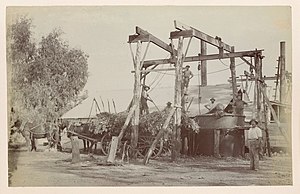

In an era before all-weather roads and powerful logging trucks, sawmills were steam-powered and often located deep in the forest with logs being snigged short distances by horses or bullocks. As the industry expanded and became more mechanised, tramways with wooden or steel rails spread throughout the bush. These tramways were also used to transport sawn material to local towns and then onwards on the State railway network to markets in Melbourne and beyond. The size of the logs combined with steep terrain and often wet conditions in the mountains limited the use of animals and steam powered winches driving elaborate "high lead" cable systems later replaced them. The Commission also operated a Washington steam winch, its own sawmill at Erica with timber tramlines and steam engines such as the climax locomotive.[50] The Commission built and operated the Tyres Valley Tramway.

Productivity increased enormously with the advent of powered chainsaws after WW2 which replaced axes to fell and crosscut large trees.[30] Around the same time, diesel and electric motors replaced steam, while mobile cranes and crawler tractors replaced dangerous man handling of logs and timber but sawmills and logging still remained a dangerous workplace.[11]

Bushfires – 1926[edit]

Bushfire had been a major focus for the newly formed Forests Commission. Throughout February 1926 uncontrolled bushfires burned across Gippsland and the Central Highlands and destroyed large areas of valuable mountain forest. Sixty lives were lost in addition to widespread damage to farms and homes.[10] The fires came to a head on 14 February, with 31 deaths recorded at Warburton. Other areas affected include Noojee, Kinglake, Erica and the Dandenong Ranges. The Minister for Forests, Mr Horace Frank Richardson and a couple of the Commissioners, William James Code and Alfred Vernon Galbraith were on tour in Gippsland and were almost dangerously caught in the fires on 4 February near the Haunted Hills west of Moe.[51] The Commission later produced a film to raise money for fire victims.[52]

During the same decade the earliest recorded use of fire by a Government land manager to reduce fuel levels on public land occurred in Victoria.[53]

Victorian timbers[edit]

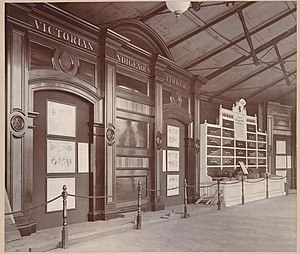

Early foresters, sawmillers and timber merchants recognised the unique qualities of Victorian hardwood timbers and the Government was keen to promote them to the world market. Research into native timbers began sometime after Federation in 1901 and progressed with the publication of Richard Thomas Bakers's important work "Hardwoods of Australia and their Economics" in 1919.[11]

Two of the Principals from the Victorian School of Forestry, first Charles Edward Carter in the 1920s, followed by Alan Eddy in the 1950s did foundation research into the properties of timber.[11] Herbert Eric Dadswell[54] worked with both Carter and Eddy at the Forest Products Division of the CSIRO at Highett in Melbourne from 1929 until 1964. He tested thousands of timber samples and his authoritative descriptions of Australian hardwoods included engineering properties such as strength, hardness, appearance, suitably for joinery, resistance to termites, durability and so on.[9] The huge Dadswell wood collection now resides with the CSIRO and contains over 45,000 samples representing 10,000 species while a subset are kept in the Forestry School museum at Creswick.[55]

Some eucalypts, particularly mountain ash, were very prone to suffer from collapse in the seasoning (drying) process and work focused on steam reconditioning.[11] This problem created some initial reluctance from Victorian sawmillers to invest in timber seasoning so an experimental workshop and kilns were established by the Commission at the Newport Seasoning Works from 1911 until it closed in 1956 under controversial circumstances.[56] By far the greatest proportion of dressed timber for internal work, joinery and furniture was imported in the 1920s mainly from America and Scandinavia. The Commission sought to improve the position of native hardwoods in the market and put the Victorian industry on a sound footing. The pioneering work at Newport together with the CSIRO bore fruit and by 1931 it was estimated that 80% of flooring laid down in Melbourne was kiln-dried Mountain Ash milled from the State's forests.[11] Some of the finished timber from Newport was shipped to London to feature as flooring in Australia's High Commission building.

But despite these efforts, as late as the 1960s there was still some resistance from architects, builders, joiners and home owners to Australian hardwoods so the Commission constructed a timber display pavilion at the Royal Melbourne Showgrounds in 1966. This initiative led to the establishment of the Timber Promotions Council (TPC) in 1969 in partnership with Victorian Sawmillers Association and timber merchants.[11] The TPC undertook research and development, marketing and training into the use of Victorian timber. It also offered an advisory service to builders, architects and the public. A levy was generated from sawlog sales to fund the TPC until it was revoked in 2005.[57] The Victorian Association of Forest Industries (VAFI) in now the peak industry body.

Timber licensing[edit]

During the late 1800s the absence of clear forest policies and regulations generally encouraged a sawmillers free-for-all. The Minister for Lands and Agriculture in a report to Parliament described the licence system as “no more effectual method of legalising the destruction of timber could have been devised”.[11] However, new controls resulted in sawmills and sleeper cutters being allocated sole rights to an area of forest to exploit but by the early 1920s this system was gradually replaced by one where royalty was paid based on the quantity of sawn timber produced. A more modern licensing arrangement was formally introduced in 1950.

Towards a national forest policy[edit]

1920 saw Australia's first Premiers Conference that was to consider "forest" matters. The meeting concluded that 9.8 million hectares nationally should be permanently reserved as forest to secure timber supplies. The Victorian component was to be 2.2 million hectares.[11][9] Later in 1928/29 the first British Empire Forestry Conference was held in Australia. The conference, among other things, helped focus attention on the need for the establishment of more secure forest reserves.[9]

Meanwhile, the Forests Commission, sawmillers and the Melbourne and Metropolitan Board of Works all lobbied for more land. The 47000 ha Upper Yarra catchment was added to the existing Board managed watersheds in 1928.[58]

By the start of the 20th century, most of the giant trees reported by Von Mueller and others were being lost to bushfires, timber splitters or clearing and efforts were mounting by local communities and conservation groups such as the Field Naturalists Club of Victoria and the ANA to set aside forests near Marysville and protect them against logging.[59] Prominent individuals such as painter Arthur Streeton noted the "endless beauty of the green and living forest" while Professor Ernst Johannes Hartung of Melbourne University proclaimed the Valley ought to be preserved as a rare botanical and zoological sanctuary. The Minister for Forests, Horace Frank Richardson responded by creating a one square mile reservation (640 acres) in January 1929 to be known as the Cumberland Memorial Scenic Reserve,[60] dedicated to returned soldiers. It included both the Cora Lynn and Cumberland Falls as well as a "sample acre" of tall trees set aside by the Commission. A sawmill was then established on the eastern edge of the new scenic reserve which operated until 1970. But the new reserve did not placate the critics and the dispute dragged on for more than 20 years and was never satisfactorily resolved.[7][30] The reserve survived the 1939 bushfires.

Furthermore, the Minister for Lands, David Swan Oman, stated in 1921 that he would no longer consult with the Forests Commission over land settlement. The test came in 1923 in the densely forested Otway Ranges over a proposal to clear 27,000 acres for farming near the Heytesbury Soldier settlement scheme. In June 1925, after pressure from sawmillers, conservation groups and Melbourne newspapers the Government finally rejected the idea. It is claimed this dispute contributed to the early resignation of the Forests Commission's first chairman, Owen Jones, who had been a strong and vocal opponent.[7]

Also during the 1920s experiments with eucalyptus pulp and timber treatment occurred, concerns about imports of timber (from interstate and overseas) continued to be expressed.

1930s – Great Depression[edit]

The trajectory of the Forests Commission from its inception in 1918 until the beginning of WW2 was one of periodic political conflict, varying budgets but almost continuous organisational expansion and relative autonomy.[15]

Although revenue from timber sales declined during the Great Depression the Government channelled substantial funds to the Commission for unemployment relief works which were well suited to unskilled manual labour such as firebreak slashing, silvicultural thinning, weed spraying and rabbit control. By 1935–36 the Commission employed almost 9,000 men in relief works and a further 1,200 boys under a "Youth for Conservation Plan".[15] One success story was at "Boys Camp Archived 9 August 2018 at the Wayback Machine" near Noojee which was made possible with the support of two prominent Melbourne businessmen and philanthropists, Herbert Robinson Brooks and George Richard Nicholas[61] together with the Chairman of the Forests Commission Alfred Vernon Galbraith.[62]

A large amount of effort was directed towards building supporting infrastructure, often in remote areas such as works depots and offices, houses for staff, roads, water supply dams and fire spotting towers. One example was Bill Ah Chow who was a legendary bushman of East Gippsland and became fire lookout at Mt Nugong in the late 1930s.[10]

By the eve of the Second World War, Victorian community attitudes had turned away from the century-long campaign to unlock ‘the waste lands of the Crown’ for private settlement.[15]

Black Friday bushfires – 1939[edit]

Considered in terms of both loss of property and loss of life, the Black Friday bushfires on 13 January 1939 fires were one of the worst disasters to have occurred in Australia and certainly the worst bushfire up to that time.[63] In terms of the total area burnt, the 1939 Black Friday fires remain the states second largest, burning 2 million hectares, 69 sawmills were destroyed, 71 people died, and several towns were entirely obliterated. Among those killed were four men from the Commission.

It is with very deep regret that the Commission records the tragic deaths of four officers and employees of the Department in the bush fires of January last. They were:

* James Hartley Barling, Forester, aged 31 years.

* Charles Isaac Demby, Forest Overseer, aged 56 years.

* Hedley John West, Forest Foreman, aged 40 years.

* Hugh McKinnon, Forest Employee, aged 57 years.

Messrs. Barling and Demby, who were the first victims of the fires, lost their lives near Toolangi on Sunday, 8th January, Mr. West in the Rubicon blaze on Wednesday, 10th January, whilst Mr. McKinnon died in hospital from injuries received on Friday, 13th January, in the Loch Valley district near Noojee.

This was the first occasion on which members of the Commission's staff lost their lives as a direct result of forest fires. These men died in faithful discharge of their duty, and their unflinching heroism in the face of fearful odds must serve as an inspiration not only to their colleagues but also to every individual in the community ..... 1938–39 Annual Report.

Putting aside large conflagrations of cities like the Great Fire of Meireki or the Great Fire of London, perhaps the world's worst bushfire was at Peshtigo in Wisconsin in 1871, which burnt nearly 1.2 million acres, destroyed twelve communities and killed between 1500 and 2500 people. Now largely forgotten, Peshtigo was overshadowed by the Great Fire of Chicago that occurred on the same day.

Stretton Royal Commission[edit]

The subsequent Royal Commission conducted by Judge Leonard Stretton has been described as one of the most significant inquiries in the history of Victorian public administration.[9] Its recommendations led to sweeping changes including stringent regulation of burning and fire safety measures for sawmills, grazing licensees and the general public, the compulsory construction of dugouts at forest sawmills, increasing the forest roads network and firebreaks, construction of forest dams, fire towers and aerial patrols linked by the Commission's radio network to ground observers.[64]

Prior to 13 January 1939, many fires were already burning. Some of the fires started as early as December 1938, but most of them started in the first week of January 1939. Some of these fires could not be extinguished. Others were left unattended, or as Judge Stretton wrote, the fires were allowed to burn "under control", as it was falsely and dangerously called. Most of the fires Stretton declared, with almost biblical gravity, were lit by the hand of man.[64] There was a huge wave of criticism in the press of the Government, the Forest Commissions and the Melbourne and Metropolitan Board of Works for an overly zealous fire-suppression policy. The Commission, in turn, blamed landholders for recklessly setting fires at dangerous times.[34]

As a consequence of Judge Stretton's scathing report, the Forests Commission gained additional funding and took responsibility for fire protection on all public land including State forests, unoccupied Crown Lands and National Parks plus a buffer extending one mile beyond their boundaries on to private land and its responsibilities grew in one leap from 2.4 million to 6.5 million hectares.

Stretton also examined the inevitability of fire in the Australian bush and heard evidence from foresters, graziers, sawmillers and academics whether it was best to let fires burn because they were a part of a natural protective cycle or to combat them to defend people and the forests. Importantly, his balanced deliberations officially sanctioned and encouraged fuel reduction burning to minimise future risks.[64] The newly appointed Fire Protection Officer, Alfred Oscar Lawrence immediately set about the huge challenge of rebuilding a highly organised and motivated fire fighting force, lifting staff morale, introducing more RAAF fire spotting patrols, new fire towers and lookouts, modern vehicles, fire tankers and equipment such as powered pumps and crawler tractors, as well as a statewide radio communications network, VL3AA.[65] The Commission's communication systems were regarded at the time to be more technically advanced than the police and the military. These pioneering efforts were directed by Geoff Weste.[11][10]

Further major fires later in the 1943–44 Victorian bushfires season and another Royal Commission chaired by Judge Stretton was a key factor in the founding of the Country Fire Authority (CFA) for fire suppression on rural land.[9] Prior to the creation of the CFA the Forests Commission had, to some extent, been supporting individual volunteer brigades which had formed across rural Victoria in the preceding decades.[9] Alf Lawrence was appointed a member of the new Board of the CFA.

Significantly, the tragic losses and Stretton's inquiries shaped and cemented Victoria's deep-seated approaches towards bushfire. Both the Forests Commission and CFA adopted clear policies to detect and suppress all bushfires and became very focused and skilled at doing it.

Inventory and Assessment[edit]

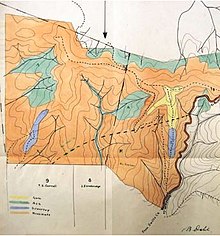

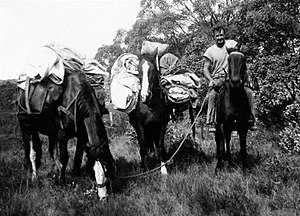

It was recognised by Sir William Schlich in his summary of British Empire forest policy in 1922 that Australia lacked many of the skills to undertake inventory needed to prepare proper working plans. So in 1927–28, the Commission made concerted effort to recruit trained foresters from Norway. They included Bernhard Johannessen, Kristian Drangsholt and Bjarne Dahl who formed the nucleus of a forest assessment branch.[10] In an era before there were many roads, these foresters travelled on horses into the remote forests of Victoria. Base lines were surveyed and the forest divided into one-chain (20 metre) strips. It was arduous work with an axeman clearing a straight path through the bush, a chainman following to measure distances while an assessor counted and assessed the trees. An aneroid barometer was carried to mark out 50 feet contour levels. Later, by joining-the-dots, they produced the first hand-drawn and coloured topographical maps of the forest which were rare before the War. Often working in trackless bush accidents were common and help was far away. Drangsholt almost drowned as he tried to cross the flooded Thomson River to reach the sanctuary of Aberfeldy. During Bjarne Dahl's long career he probably saw more of Victoria than most foresters ever did.[10] He died in 1993 and left his entire estate, a sizable sum, to the Forests Commission which is now managed in a trust Archived 11 August 2018 at the Wayback Machine to focus on the eucalypts. He wrote:

I was once a Chief Forester and I owe the Forests Commission of Victoria a great deal of gratitude for giving me in 1928 the opportunity to make good in my profession..... Bjarne Dahl.

Owen Jones,[66] the young Welsh Chairman of the newly formed Forests Commission had enlisted as one of Britain's original "Warbirds" in the Royal Flying Corps during WW1 and had long championed the idea of forest surveying, mapping and assessment from aerial photographs so in 1928 the Commission undertook its first major aerial photography project over 15,000 acres of forest.[67] During the second world war, large areas of Victoria were photographed by RAAF aircrews and later used by various state government authorities to produce orthophoto maps. By 1945 aerial photography of 13,000 square miles (3.4 M ha) of forest was completed, including much of the inaccessible forest in the eastern ranges.[67]

After the War, stip assessments continued but were focused in the eastern ranges, with forest mapping and classification carried out using interpretation of aerial photography undertaken by the RAAF. Assessments were in remote locations with access by 4WD tracks, but also still by pack horse, with staff based in canvas tents in the mountain forests often in grassy clearings in high elevation snow gum woodland.

From the mid-1950s, there was a transition from strip assessments to using fixed sample plots combined with new computer programming techniques to calculate volumes of both sawlog and pulpwood.

In 1964, a network of Continuous Forest Inventory (CFI) plots were established for measuring periodic growth, commencing initially in the Wombat forest, then Mt Cole, Barmah Forest and also conifer plantations.

As aerial photographic cameras developed and got cheaper in the 1960s and ‘70s all forest services began purchasing their own 70 mm medium format camera equipment and modifying small civilian aircraft to undertake regular surveys collecting information on things like vegetation, logging areas, new road works and bushfire history.[11] Photos were interpreted using stereoplotting equipment such as a Zeiss Aero Sketchmaster.[68]

The Commission continued to make a sizable effort in aerial photography, forest inventory, mapping, tree measurement, growth monitoring and analysis. This information was used not only to identify timber resources but also to monitor forest health and calculate sustainable yields and allowable harvesting levels.[11]

Pulpwood[edit]

From its earliest days, the Commission had promoted using forest and sawmill waste for the production of wood pulp. Industry eventually began to show some interest and in December 1936, the Commission led by A.V. Galbraith and Sir Herbert Gepp from Australian Paper Manufacturers Ltd (APM) finalised a pioneering legislated agreement which gave certain pulpwood rights to the company for fifty years over about 200,000 ha of State forest. The Commission retained control over the pulpwood harvesting operations to ensure that pulpwood remain secondary to the utilisation of the more valuable types of produce such as sawlogs, poles and piles, the main source being of the ash eucalyptus from both mature trees and thinning's.[69]

The company proceeded to establish a plant at Maryvale in Gippsland for the manufacture of Kraft papers. It came into production in October 1939 and for some years much of its feedstock came from the 1939 fire-killed ash forest.[70]

1940s – Bushfire recovery and the war years[edit]

Many Commission employees, timber workers and those from forest sawmills volunteered for military service in WW2 with some joining units deployed to the UK and other places as the 2/2 Forestry Company in the Royal Australian Engineers (RAE) who served with distinction to produce timber for the war effort.[71] Others served back at home by continuing the salvage of the fire killed forest as well as producing firewood and charcoal for domestic use.

Fire salvage[edit]

Victoria's forests were devastated to an extent that was unprecedented within living memory and the impact of the 1939 bushfires dominated management thought and action for much of the next ten years. Salvage of fire-killed timber became an urgent and dominant task that was still consuming resources and effort of the Commission a decade and a half later.[72]

It was estimated that over 6 million cubic metres of timber needed to be salvaged. A massive task made more difficult by labour shortages caused by the Second World War. In fact, there was so much material that some of the logs were harvested and stockpiled in huge dumps in creek beds and covered with soil and treeferns or wetted down with sprinklers to stop them from cracking only to be recovered many years later.[10]

Reforestation[edit]

Reforestation of degraded mining areas near Creswick had begun with John la Gerche in the 1890s.

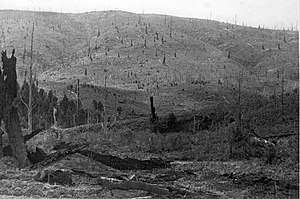

Considerable effort also went into reforestation at Powelltown and the Toorongo Plateau near Noojee during the 1940s and 1950s. These mountain forests of Eucalyptus regnans, E. delegatensis and E. nitens had been killed by bushfire in 1926, and then regenerated naturally. However, significant bushfires again in 1932 and 1939 killed the young eucalypt regrowth before it was old enough to produce enough seed and the area was replaced by scrubland.[17][10] The program lapsed but was renewed in the late 1980s and early 1990s with funding from the Timber Industry Strategy.

The steep hills of the Strzelecki Ranges in South Gippsland had been cleared in the 1880s, but abandoned because it proved too hard to farm successfully. The scrub, blackberries, rabbits and weeds then took over and the area became known locally as the Heartbreak Hills.[73] So the Commission commenced a massive reforestation scheme in the 1930s which continued for the next 60 years or so. The Commission purchased derelict farmland at Allambee (1947–49), Childers (1946–48) and Halls Rd at Boolarra (1949) and by June 1986 the FCV had purchased over 400 properties with a total area of 28000 ha. At the same time, APM held a similar estate of 24000 ha purchased land plus 8600 ha of crown land leasehold.[10]

Similarly, degraded farmland in the Otway Ranges was purchased and replanted from the early 1930s,[17] including a trial plot of Californian Redwoods, Sequoia sempervirens in the Aire Valley planted in 1936. Their initial growth was disappointingly slow but they are now about 60 metres tall and have become a popular tourist destination in the Otways National Park. Most of the planting work was done by postwar immigrants and refugees from Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, Poland, Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia. The first batch of "Balts" as they became known, arrived at Colac in April 1949 and lived in a Forests Commission camp next the Redwoods.[74]

Reforestation was achieved by clearing the scrub using heavy machines and either broadcast seeding, or by planting with seedlings. The reforestation of the Strzelecki Ranges and the Otways proved successful and the plantations were included in the area vested with the Victorian Plantations Corporation in 1993.[10]

Reforestation works using Cypress Pine Callitris, were carried out in the dry Hattah – Kulkyne forest in northwest Victoria in 1937–38 to combat soil erosion resulting from the excessive clearing of mallee woodlands for farming. However, this work was severely hampered by large rabbit populations and the vagaries of the weather.[10]

Firewood emergency[edit]

Up until the late 1930s, coal was the main fuel for domestic heating and cooking, industry and electricity for metropolitan Melbourne as well as Victoria's steam trains. But World War II drew large numbers of men, led to a major escalation in Australia's heavy industry, placing urgent demands for fuel and power as well as a reduction in the supply of black coal from both New South Wales and overseas. Imported petrol and oil were also severely rationed. (see Charcoal).

One of the pressing requirements on the Forests Commission during the War was to organise emergency supplies of firewood for military and civilian heating and cooking, and as a substitute for coal for locomotives exacerbated by earlier explosion at the State Coal mine at Wonthaggi in 1937. In response, the Commission established the State Fuel Branch to increase production and control distribution which was housed at the Flinders Street railway buildings. The Victorian Railways provided special firewood trains but transport and distribution of the bulky firewood dogged the project.[10]

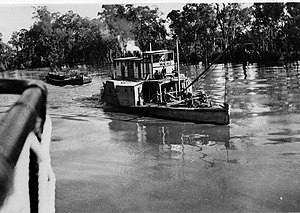

Prior to the War, less than 1,000 imperial tons of firewood came into Melbourne each week and estimates ranged up to a 300,000 ton short-fall, but in its first year of operation, the Forests Commission dispatched some 253,668 tons into the city. Much of the firewood came from 1939 bushfire salvage operations, but later in 1942, the Paddle Steamer Hero Archived 9 August 2018 at the Wayback Machine and two barges (John Campbell and Canally) were purchased by the Commission from Arbuthnot Sawmills to transport much needed redgum firewood from Barmah Forest to the Echuca wharf and then by rail to Melbourne. Most of the labour was provided by some 700 Italian and German POWs and internees[75] who were accommodated in special forest camps Archived 9 August 2018 at the Wayback Machine at Echuca, Mt Disappointment, Tatura, Rushworth and Graytown.[11] By the end of 1943 they produced 148,844 tons at an average rate of 11.3 tons per man each week.

Closer to Melbourne, the Country Roads Board undertook special construction projects to provide access to firewood areas. And firewood depots were set up in conjunction with Victorian Railways at Brookwood, Toorak, Fitzroy and Kew. The City of South Melbourne provided a facility where one-foot blocks of wood were cut from 5-foot and 7-foot billets and stored. Four-hundred-and-ninety-six fuel merchants were registered to distribute the firewood across suburban Melbourne.[10]

Later, large bushfires in 1944 near Yallourn open-cut mine caused further restrictions on coal and briquettes. Homeowners were only permitted to buy coal for heating water and firewood was provided to the Victorian Railways for locomotives shunting in marshalling yards throughout the State.[10]

After the War, a seven-week national coal miners’ strike in 1949 brought industry to a grinding halt and black coal was no longer available to Victoria from interstate. The State Electricity Commission could not keep-up full production of briquettes.[76] There were also restrictions with electricity which were not lifted until 1953. In December 1950, a fire at the Brookwood depot[77] destroyed over 3,300 tons of firewood.[10]

The Emergency Firewood Project continued long after the war and over the period from 1941 to 1954, nearly 2 million tons of firewood was produced by the FCV.[10]

Charcoal[edit]

During WW2, petrol was rationed and largely reserved for essential services or the military.[78] In 1941 the Government restricted motorists to 1,000 miles per year (32 km/week) so many simply put their cars up on blocks for the duration and switched to public transport. Others were offered an alternative source of energy: charcoal to burn in gas converters attached to their cars. They had a reputation for being inefficient, underpowered, dirty, belching black smoke, catching fire and occasionally exploding.[79]

Forests Commission firefighting vehicles were exempt from the petrol restrictions. District Foresters were authorised to issue petrol coupons for timber industry trucks, which, in the absence of private cars and utes, often served as family transport too. Country school buses were fitted with gas converters and on declared days of Acute Fire Danger they were banned. Some of Melbourne's buses also ran on charcoal.[10]

The task of ensuring adequate supplies of charcoal fell to the Commission. It subsequently formed the State Charcoal Branch to organise the increased production of charcoal, to build up reserves to meet emergencies and to regulate the cost to consumers. The assistance of an expert Advisory Panel, representing charcoal producers, manufacturers and distributors of vehicle gas equipment, the Department of Supply and Development, and the Victorian Automobile Chamber of Commerce, was enlisted under the Chairman of the Forests Commission, Alfred Vernon Galbraith. Preliminary arrangements were made for bag supplies, for railway sidings in Melbourne, and for processing of charcoal bought by the Branch in excess of the requirements of private grading firms. In its first year, 17,421 tons of charcoal were produced compared with 1,650 tons before the War.[80] Production peaked at 38,922 tons in 1942–43.[80]

An estimated 221 kilns and 12 pits were producing charcoal by the middle of 1942. Some of the labour was provided by Italian wartime internees. There were also over 600 commercial kilns operating mostly on private property. At least 50 to 60 private charcoal retorts were operating in the Barmah forest alone.

Kurth Kiln was built by the Commission near Gembrook as the only commercially sized charcoal facility in Victoria which could operate continuously. The kiln was in full production by mid-1942, but transport difficulties and an oversupply of charcoal from private operators meant the kiln was used only intermittently during 1943 and was shut down soon after. The unique site is now of historical and scientific significance.

Minor forest produce[edit]

In addition to the main commodity of sawlogs and pulpwood, the Commission supplied a wide assortment of minor forest products including salt, eucalyptus oil and tea tree from the mallee deserts, wattle bark for tanneries. gravel, sand, charcoal, railway sleepers, clothes line props, split fence palings, chopping blocks for country shows, power poles, fence posts and rails, timber for wood distillation to produce chemicals, Christmas trees as well as specialty durable timbers for boats and marine jetties.[10] They controlled licences and leases, cattle grazing along the Murray River and some alpine areas as well as hundreds of apiary sites. Cork oak plantations were trialled but proved unsuccessful.[81] But the Commission owned a number of poplar plantations along the Murray River and the timber was used to make redhead matches untilBryant and May switched its manufacturing operations from Richmond to Sweden in the 1980s.

Baron Ferdinand von Meuller, the Government Botanist encouraged Joseph Bosisto, a Victorian pharmacist, to investigate the essential oils of the eucalyptus during the 1850s. Based on the success of this work eucalyptus oil became an important industry in the box-ironbark forests during the post gold-rush era of the 1870s. It was a very labour-intensive operation with coppice cut by hand and placed in steam stills. The oil was often described as Australia's natural wonder and was exported to a growing international market, mostly for medicinal purposes. Eucalyptus oil was in particularly big demand during the global influenza pandemic of 1918–19. A distillation plant that was established by the Forests Commission at Wellsford State Forest[82] near Bendigo in 1926. The Principal of the Victorian School of Forestry, Edwin James Semmens, undertook much of the pioneering chemistry into the composition of eucalyptus oil.[11] His steam extraction kilns are in the museum at the school. Australian production peaked in the 1940s but sources from Spain and Portugal began to dominate supply from the 1950s. The world consumption of eucalyptus oil is now estimated to be about 3000 tonnes per annum and China supplies about 75%, although Australia continues to produce high-grade oils, mainly from blue mallee (E. polybractea).[83]

1950s – Post war housing boom[edit]

In the immediate postwar period the Forests Commission increased its intake of students at the Victorian School of Forestry to meet the demands on the States forests and the timber needs of the housing boom.[84][85] An interactive map reveals the extent Melbourne's suburban post-war growth.

The destruction by the 1939 fire in the Central Highlands around Melbourne and conclusion of the massive salvage operation forced a major movement of timber production into East Gippsland and northeast Victoria. The demands of the new sawmills in regional towns, and the shift of the timber industry to the vast untapped forests transformed logging of Victoria's native forests from small operations to ones with large capital investments in machinery and trucks.[11]

The advent of more powerful bulldozers, crawler tractors and geared haulage trucks dramatically changed logging practices. It became feasible for log trucks to haul directly from the landing in the forest to town-based sawmills within a few hours. Country towns then became the hub of activity, rather than the mills deeper in the forest that was characteristic of the earlier period, and settlements like Heyfield, Mansfield, Myrtleford, Orbost and Swifts Creek grew into busy centres based on the timber industry.[15] Moreover, after learning valuable lessons from the 1939 bushfires and tragic loss of life the Commission used its Licensing and Royalty powers to regulate where new mills could be built.

Road and bridge building[edit]

The result of the eastwards shift was a massive expansion of the forest roads and tracks network by almost a thousand kilometres in some years.[69] Major construction projects such as the Tamboritha and Moroka Roads[86] north of Licola in Gippsland and the Big River Road in northeast Victoria were blasted through the rugged mountains to access new timber resources and provide much needed fire access. However, the ever-expanding road and wooden bridge network and the need for expensive maintenance in remote locations created long term funding headaches. Winter snows and storms caused large trees to fall and flash floods proved havoc that required a big engineering program each spring and summer.[87] Large works crews with a fleet of trucks, bulldozers and graders were needed to keep the roads and 4WD fire tracks open and to repair or replace damaged timber bridges. The Commission's own powder monkeys blasted and crushed rock from large quarries in the forest to provide much needed surfacing gravel.[10]

Vehicles and equipment[edit]

The advent of motor vehicles, aircraft, radios and telephones extended the knowledge and reach of management as well as operational surveillance and control. It gave the Commission better scope to deal with its greatly increased area of bushfire responsibility. The Commission acquired several surplus WW2 army vehicles and equipment as the forest road network rapidly expanded in the wake of the Stretton Royal Commission into the 1939 Black Friday bushfires and the appointment of the new Chief Fire Officer, Alfred Oscar Lawrence.[10]

The Forests Commission acquired a large fleet of surplus 4WDs after WW2 such as heavy American armour-plated White scout cars, Blitz trucks and 4X4 tankers from the RAAF base at Amberley. A few Norton Dominator 77 motorbikes complete with sidecars were also purchased but these were progressively replaced by British Series 1 Land Rovers in the 1950s and then by Toyota 40 series Land Cruisers in the early 1960s.

Army surplus Coventry Climax and Pacific Marine fire pumps as well as new radio equipment were also purchased.

The Commission placed increased emphasis on fire research and development right through the 1960s and 1970s and undertook some innovative work with aerial fire bombing and fire equipment. Initially, fire fighting appliances such as Bedford tankers and locally designed rubber Slip-On-Units that fitted onto a tray bodied 4WD vehicle were rugged and rudimentary but developed over time at its Altona workshops.[10]

Changing relationships with the timber industry[edit]

During the 1950s, a number of factors led to a realignment of the relationship between the timber industry and the Forests Commission. These included post war housing boom, the movement eastwards after the end of the 1939 fire salvage, larger sawmills situated in small country towns, rather than deep in the forest, combined with more powerful logging equipment and haulage trucks.

The Commission focused on its legislative and regulatory responsibilities of managing the states 7.1 million hectare forest estate. In addition to land management, conservation and fire protection the key commercial tasks involved inventory and assessment, mapping, preparing working plans, growth monitoring, calculating sustainable yield and allowable cuts, marketing and sales, licensing and approvals. Timber harvesting roles involved setting standards and prescriptions, construction and maintenance of major roads and bridges, supervision and compliance of logging operations. The Commission also took responsibility for all post-harvest regeneration treatments and depending on the forest type and technique required, this included seed collection and extraction, site preparation, slash burning, aerial seeding and follow up surveys.[10]

The timber industry centred on private sector business, harvesting and cartage contractors engaged directly by sawmills and APM pulpmill, all with large capital investments in plant and machinery.[11]

The Commission meanwhile progressively divested itself of its logging equipment, timber tramways, the State sawmill at Erica and the Newport seasoning works during the later part of the 1950s[17] to create a much clearer separation between itself and the timber industry.

In January 1950, a new royalty equation system was introduced that took account of the distance that logs were hauled from the forest to the sawmill, the quality and size of the logs together with the distance to central markets in Melbourne. It was intended to reduce wastage but also be simple and equitable and with various modifications still operates today.[11]

Department restructure – 1956[edit]

While there had been many administrative changes in the late 1800s, the structure of the Forests Commission had remained relatively stable since its formation in 1918. Until about 1926, there were no defined boundaries and management was based on how far foresters could travel by bike or horse from their offices in small country towns because there were very few motor vehicles or forest roads.

Major reorganisation commenced in 1956 under the direction of Commissioner, Alfred Oscar Lawrence, and officially took effect from 1 July 1957, foreshadowing proclamation of the Forests Act 1958.[10] The Plantations and Hardwood Forest groups were amalgamated and the State subdivided into 56 Forest Districts, to become the basic units of all field management which were led by District Foresters Officers (DFOs). Districts were grouped into seven territorial Divisions, each with a Divisional Forester replacing the previous Chief Inspector position. Head Office was arranged into six divisions; Forest Management, Operations, Protection, Economics and Marketing, Education and Research, and Administration. Most of the Commissions 1400 staff and crew were field-based with a small Head Office cohort of about 300 people.[17]

This configuration remained largely unchanged until the creation of Conservation Forests and Lands (CFL) in 1983. District boundaries still exist to this day and follow natural topography such as ridges and streams as well as the forest road network.[10]

Legislation change – 1958[edit]

1958 saw a major revision of three pieces of complementary legislation – the Forests Act, Country Fire Authority (CFA) Act and the Land Act. The aim was to set a bold new framework for the future of Victoria's public land estate and provide a suite of supporting regulations. It also aimed to bring all the legislation into alignment, give clarity, avoid duplication and confusing overlaps. For example, many of the legal powers for Forests Commission staff relating to fire suppression are drawn from the CFA Act. The legislative package proved robust and remains largely intact today. The first National Parks Act was passed only two years earlier in 1956 but had a major revision in 1975.

In 1959, building on a similar model to APM at Maryvale, a legislative agreement was reached to supply timber to Bacchus Marsh for the Masonite Corporation for the manufacture of hardboard products.[9]

1960s – Consolidation[edit]

The Forests Commission had dominated forest management during the 1950s post war housing boom and this proved to be the peak of its influence. It entered the 1960s increasingly confident, politically powerful and well-resourced with about 130 staff.[15]

Softwood and hardwood plantations[edit]

Early foresters discovered that the physical properties of native forest hardwoods were unsuitable for some applications and plantation-grown softwoods offered the chance to replace expensive imports of Baltic Pine, Oregon and other timbers with domestic supplies. Several exotic softwood species had been trialled but Pinus radiata had been found that its growth in Victorian conditions was sufficiently promising for commercial planting to begin from 1880.[9]

Initially, the goals were simply to rehabilitate land cleared during the goldrush, provide timber and avoid cost and unreliability of imported timber, generate revenue and create jobs through local sawmills. Commercial financial returns became a more important objective following increased investment with the plantations expansion program.[10]

Experimental pine plantations were established under the stewardship of John Johnstone, the Victorian Superintendent of Plantations (and often overlooked founder of the forestry school at Creswick). These were at Frankston and Harcourt (1909), Wilsons Promontory (1910), Bright (1916), Port Campbell/Waarre (1919), Anglesea (1923) and Mount Difficult (1925). The largest plot was some 2,500 acres associated with the new McLeod Prison farm on French Island (1911). However, nearly all these plantings failed due to poor soil and site conditions, but valuable silvicultural lessons were learned. The earlier success of radiata pine had partly given rise to the fallacy that it could grow anywhere.[10]

Activity picked up once again in the 1930s with unemployment relief schemes during the Great Depression. The war years saw activity again fall away sharply while after the war there was a new focus on developing native forests in eastern Victoria owing to the conclusion of the 1939 fire salvage and to provide timber for post-war housing construction.[17] However, the Strzelecki reforestation program got underway in the 1930s with planting of both softwoods and hardwoods on abandoned farmland.

In 1949 the Commonwealth Forestry and Timber Bureau proposed a national planting program to make Australia more self-reliant in timber products after the shortages experienced during the war. The threat of introduced sirex woodwasp in the early 1950s and its eventual discovery on the Australian mainland in 1961 brought the softwood plantation program into question. However, quarantine and control measure was put in place.[10]

Separately in 1952 a private company, Softwood Holdings, began to establish its own plantations in South West Victoria. This was followed shortly after by construction of a new sawmill at Dartmoor in 1954 which drew logs from both government plantations and private sources. Associated Kiln Dryers (AKD) mill at Colac followed in 1954. It was a similar pattern across the border near Mt Gambier in South Australia and the beginning of what became known as the "green triangle".[88]

But the big step came in 1961, when the Chairman of the Forest Commission, Alf Lawrence attended the World Forestry Conference in São Paulo Brazil and upon his return took a bold decision to commit Victoria to a massive Plantation Expansion (PX) program which initiated nearly four decades of rapid plantation establishment.[85] At that stage, softwoods were still being imported in large quantities and it was also believed that softwoods could not only relieve the pressure on native forests but make Australia self-sufficient in timber resources.[11]

A new Ministerial Australian Forestry Council was formed in 1964 with one of its first decisions being to further raise the national softwood target, with the Commonwealth agreeing to provide loan monies to the States to plant 30,000 hectares of softwoods per year for 35 years. Victoria took up the challenge by establishing and maintaining its plantations at nearly half the average cost of the other States.[9]

Planting peaked in 1969 with a record 5,183 ha and by the end of 1982, the Commission had established 87,000 hectares of softwood plantations, a five-fold increase since 1940. Softwood plantation zones were concentrated around Bright and Myrtleford in the Ovens Valley, Portland-Rennick, Latrobe Valley-Strzelecki Ranges, Ballarat-Creswick, Benalla-Mansfield, Upper Murray near Tallangatta-Koetong, the Otways and Central zone near Taggerty.[89]

The majority of the plantation estate consisted of Pinus radiata, with a smaller area of native hardwoods – mostly Eucalyptus regnans in the Strzelecki Ranges.

As the plantation base expanded and matured agreements were reached private mills such as Bowater-Scott (now Carter Holt Harvey) at Myrtleford in 1972 and Australian Newsprint Mill at Albury in 1980.

But there was growing disquiet from environment and community groups about the clearing of native forests and conversion to pines, together with the use of chemical sprays.[90] So in the 1970s the Commission commenced major environmental studies in North East Victoria into the effects of plantations. The studies included surveys of the biology of existing plantations compared to adjoining native forests as well as the impact of plantations on the catchment hydrology.[10]

Subsequent Land Conservation Council reviews, beginning in the 1970s, restricted the areas of new plantations on public land and by 1987 degraded farmland was being purchased for the PX program and the clearing of native forest halted.

In addition to the Commission's estate, there was considerable private investment in plantations, most notably from APM that purchased farmland close to its pulp mill at Maryvale. The company also established trees on Crown Land in the foothills of the Strzelecki Ranges on long-term lease from the Commission.

In 1992 Australia's one-millionth hectare of softwood was planted at the Ovens plantation while at the same time the Victorian Plantations Corporation (VPC) was formed to manage Victoria's publicly owned softwood plantation estate. The "cutting rights" (i.e. not the land base) were later sold to Hancock Victorian Plantations (HVP) in 1998 for $550 million.

Farm Forestry Loans[edit]

To encourage small landholders to establish woodlots, not only improve farm income but also, to contribute towards Victoria's plantation targets, legislation was enacted in late 1966 for the Commission to provide financial assistance of up to $5,000, on interest-free terms for 12 years, under the Farm Forestry Loans Scheme. By 1980, the Commission reported that 300 agreements were in place covering about 6000 ha. A separate benevolent scheme was in place to assist state schools to establish small plots of pine trees with the intent of the school retaining the revenue once they were harvested.[17]

Nurseries and extension services[edit]

The first State nursery was opened by William Ferguson at Macedon in 1872 while a nursery at Creswick opened shortly after by John La Gerche in 1887. By the late 1960s regional nurseries were located at Tallangatta (Koetong), Benalla, Trentham and Rennick near Mt Gambier to produce softwood seedlings for the Commission's Plantation Extension (PX) program, Farm Forestry Agreement holders and other private land owners.[17] A large nursery at Morwell River attached to a low-security prison produced over one million eucalypt seedlings each year while another prison at nearby Yarram at Won Wron grew pines. The prison inmates did much of the planting in the Strzeleckis.

Other extension nurseries were situated at Creswick, Macedon, Mildura and Wail near Horsham growing nearly one million native plants each year to support the trees on farms initiative (a precursor to Landcare which started later in 1986).

Private plantations companies like Australian Paper Manufacturers (APM) operated their own nurseries in Gippsland.

Aerial firefighting[edit]

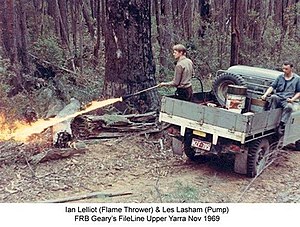

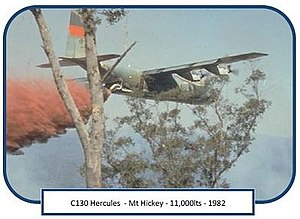

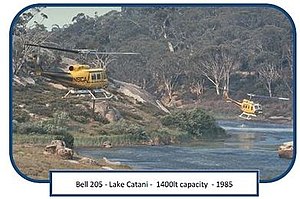

The Forets Commission also pioneered the use of aircraft for firefighting in Australia. Aircraft were used for fire bombing, crew transport, aerial incendiary work, aerial photography, infrared cameras and reconnaissance. The first fire spotting aircraft was deployed on 18 February 1930[91] (RAAF Westland Wapiti) and the first helicopter (RAAF Sikorsky S-51 Dragonfly) was trialed at Erica not long after WW2 in 1949. The organisation had been at the forefront of aircraft technology ever since. The Snowy Range airfield north of Heyfield, which is Australia's highest at 1,600 m (5,200 ft) ASL, was built by the Commission in 1961 to help fight fires across the remote alpine area. Its success led to the development of other firebombing airstrips such as the Victoria Valley in the Grampians. Getting firefighters into difficult and inaccessible terrain quickly was a perennial problem. The development of the rappelling[92] – lowering of firefighters from a hovering helicopter, was first trialled at Heyfield in 1964, an Australian first, using a Bell 47G helicopter and a two-man crew.[93] The system was in place for the following two fire seasons but lapsed until the advent of more powerful helicopters like the Bell 204 and Bell 212 in the early 1980s.

An Australian milestone – Benambra 1967[edit]

On 6 February 1967, two Piper Pawnees from Benambra near Omeo made Australia's first operational drop of fire retardant on a small lightning-strike. The drops were able to contain the remote fire long enough to enable ground crews to walk many hours across rugged terrain to reach it and make it safe. Up to that time there had been a remarkable range of experiments with different aircraft such as heavy military four engine bombers, single seat fighters and small agricultural aircraft with differing drop materials, techniques and equipment. But this was the first real firebombing job, and the beginning of modern aerial firefighting operations in Australia.[94]

Water catchments[edit]

The Royal Commission of 1897–1901 identified the importance of protecting forested water catchments. Many areas were identified for stock and domestic consumption and some large reservoirs such as Eildon and Dartmouth were primarily fed from State forest. The Commission used small speed boats to access the lake edge for fire protection and recreation patrols. Smaller weirs like Lake Glenmaggie on the Macalister River had a network of channels which fed diary irrigation districts. The water infrastructure was managed by the State Rivers and Water Supply Commission (SRWSC). Agreements and policies were progressively put in place between the Forests Commission, the SRWSC and the Soil Conservation Authority (SCA) from the 1940s to ensure water catchment protection. Melbourne's water supply catchments were treated differently and had been vested in the Melbourne and Metropolitan Board of Works in 1891. Some catchments such at the Kiewa and Rubicon were important for hydroelectricity.

The 1960s again saw more prolonged droughts and deadly bushfires on the fringes of Melbourne in 1962 and again in 1968. There were growing concerns about long term water supply security so in 1965 a Parliamentary Public Works Committee began an inquiry into future water supplies for the growing city and reported in 1967. In response to the inquiry, the Bolte Government immediately approved works for a 20 km diversion tunnel from the Thomson River and planning to begin for the construction the massive Thomson Dam in Gippsland to add considerably to water storage capacity (the Upper Yarra Dam had been completed in 1957).