Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by difficulty focusing attention, hyperactivity, and impulsive behavior.[1] Treatments generally involve behavioral therapy and/or medications (stimulants and non-stimulants).[2] ADHD is estimated to affect about 6 to 7 percent of people aged 18 and under when diagnosed via the DSM-IV criteria.[3] When diagnosed via the ICD-10 criteria, hyperkinetic disorder (the ICD-10 term for severe ADHD) gives rates between 1 and 2 percent in this age group.[4][5]

Children in North America appear to have a higher rate of ADHD than children in Africa and the Middle East - however, this may be due to differing methods of diagnosis used in different areas of the world.[6] If the same diagnostic methods are used rates are more or less the same between countries.[7]

Africa[edit]

In 2020, a meta-analysis of studies found that 7.47% of children and adolescents across Africa have ADHD.[8] ADHD was found more often in boys, at a rate of 2:1.[8] The most common form of ADHD was inattentive (2.95% of total population), followed by hyperactive/impulsive (2.77%), then combined (2.44%).[8] While differences in prevalence rate were found internationally, it is not clear whether this reflects true differences or changes in methodology.[8]

Asia[edit]

The estimated prevalence of childhood ADHD in Asia is less than 5%, which is similar to its prevalence in South America, Europe, North America, and Oceania.[6] The estimated prevalence of adult ADHD is 25.66% in the South-East Asia Region and 9.67% in the Western Pacific Region.[9]

China[edit]

Utilizing data from the WHO World Mental Health (WMH) Surveys, it is estimated that, in China (Shenzhen), the prevalence of childhood ADHD is 0.7% and the prevalence of adult ADHD is 1.8%.[10] This study also determined that for adults in China (Shenzhen) with existing ADHD, 62.8% had a history of childhood ADHD.[10] Another study utilizing systematic review estimated the prevalence of childhood ADHD in China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan to be 6.3%, with the individual regions exhibiting prevalences of 6.5%, 6.4%, and 4.2% respectively.[11] Variability in the ADHD prevalences of children in China can be attributed to differences in study methodology, socioeconomics, and dates of data collection.[11]

India[edit]

The estimated prevalence of childhood ADHD in India is 7.1%, with individual study estimates ranging from 1.30% to 28.9%.[12] Male children in India exhibited a slightly higher ADHD prevalence of 9.40% compared to 5.20% in female children.[12] Overall, the prevalence of childhood ADHD in India does not differ significantly from the global prevalence, but there may be additional stigma associated with mental disorders in India.[12]

Middle East[edit]

The estimated prevalence of ADHD in Arab countries among schoolchildren (ages 6–12 years) ranges between 7.8 and 11.1%, while it was higher, at 16%, in studies that included younger children (ages 3 to 15 years). This variation was primarily explained by methodological differences between studies.[13] However, all studies in various Arab countries revealed a male predominance of ADHD.

Saudi Arabia[edit]

The prevalence of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder was found to be 3.4% overall in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, among primary school students between the years of 2015 and 2016, with 22 children having symptoms that were both reported by their parents and teachers. The gender split among them was 3:1, with 13 (5.7%) boys and 9 (2.1%) girls.[14]

Iran[edit]

A systemic review of studies carried out in various Iranian cities between January 1990 and December 2018 revealed a prevalence of ADHD that ranged from 3.17% to 17.3%.[15] Overall, boys (5.03% to 29%) had higher numbers[16] compared to girls (2.3% to 15%).[citation needed]

Iraq[edit]

The prevalence rate of ADHD was found to be 8.67% in a cross-sectional study done in Tikrit City, Iraq in 2012–2013 among students in 6 primary schools for boys and girls. Male to female ratio was 1.87:1, and boys made up the majority of those affected (65%). 49% of them were younger than 9 years old. In this study, the inattention subtype was most prevalent (38%) followed by combined (34%) and hyperactive (28%).[17]

Lebanon[edit]

Between March 2012 and December 2012, a cross-sectional survey of 510 Arabic-speaking adolescents aged 11 to 17 years and 11 months who resided in Beirut found that 52 (10.20%) of the sample had been diagnosed with ADHD, of which 77% had the combined type and 6% had the inattentive type. 35 (67.31%) of those diagnosed were male, and 49 (94.23%) were Lebanese citizens.[18]

Qatar[edit]

Results from a cross-sectional study in Qatar Independent and Private Schools revealed that boys between the ages of 6 and 9 exhibited the most ADHD symptoms, with 16.36% of them scoring higher than the 5% threshold for the disorder on the SNAP-IV, standardized rating scale, as opposed to only 4.13% of girls in the same age group. 12.32% of the boys between the ages of 10 and 12 who took the SNAP test showed ADHD symptoms above the 5% cutoff point, and 6.08% of the girls had symptoms severe enough to warrant a clinical assessment for ADHD. In Qatari schools, the average percentage of students aged 6 to 19 with ADHD symptoms was 8.3%.[19]

Australia[edit]

The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare reports that the most recent national data on childhood and adolescent mental health (gathered in 2013–14) demonstrated that the prevalence of ADHD was 8.2% in children aged 4–11 and 6.3% in adolescents aged 12–17.[20] Severe disorders were more common among boys (10.9%) than girls (5.4%).[21] In comparison to females aged 4–11 years, the prevalence of ADHD was lower in females aged 12–17 years (2.7% vs. 5.4%), although it was roughly the same in males (9.8% vs. 10.9%).[21] An association with household income was also discovered for ADHD, with the odds of a child or adolescent being diagnosed with ADHD being 1.5 times higher in families in the lowest tercile of household income compared to those in the highest tercile.[22] The prevalence of childhood ADHD in Oceania does not significantly differ from South America, North America, Europe, and Asia.[6]

Europe[edit]

Germany[edit]

A 2008 evaluation of the “KiGGS” survey, monitoring 14,836 girls and boys (age between 3 and 17 years), showed that 4.8% of the participants had an ADHD diagnosis. While 7.9% of all boys had ADHD, only 1.8% girls had it, too. Another 4.9% of the participants (6.4% boys : 3.6% girls) were suspected ADHD cases, because they showed a rate ≥7 on the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) scale. The number of ADHD diagnoses was 1.5% (2.4% : 0.6%) among preschool children (3–6 years old), 5,3 % (8.7% : 1.9%) at age 7–10 years, and had its peak at 7.1% (11.3% : 3.0%) in the age group of 11–13 years. Among 14 to 17 years old adolescents the rate was 5.6% (9.4% : 1.8%).[23]

Spain[edit]

Rates in Spain are estimated at 6.8% among people under 18.[24]

United Kingdom[edit]

Estimates of the prevalence of childhood ADHD in the United Kingdom (UK) ranges from 0.2% to 2.2%, varying by the study methodology.[25][26][27] The estimated adult ADHD prevalence in the UK is 0.1%.[28][25] In some parts of England, there were waiting lists of five years or more for ADHD adult diagnostic assessment in 2019.[29]

North America[edit]

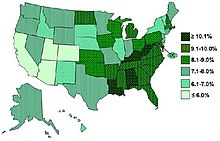

In the United States it is diagnosed in 2-16 percent of school children.[31] The rates of diagnosis and treatment of ADHD are much higher on the east coast of the United States than on its west coast.[32] The frequency of the diagnosis differs between male children (10%) and female children (4%) in the United States.[33] This difference between genders may reflect either a difference in susceptibility or that females with ADHD are less likely to be diagnosed than males.[34] Boys outnumber girls across all three subtyping categories, but the exact magnitude of these differences seems to depend on both the informant (parent, teacher, etc.) and the subtype. In two community-based investigations, conducted by DuPaul and associates, boys outnumbered girls by only 2.2:1 in parent-generated samples and 2.3:1 in teacher-based input.[35]

South America[edit]

The estimated prevalence of symptomatic adult ADHD in the Region of the Americas (North America and South America) is 6.06%.[9] The estimated prevalence of childhood ADHD in South America is 11.8%.[6][36] This is not significantly different from North America, Europe, Oceania, or Asia.[36][6] The estimated childhood ADHD prevalences for Colombia, Peru, and Brazil are 1.2%, 0.8%, and 2.5% respectively.[10] The estimated adult ADHD prevalences for Colombia, Peru, and Brazil are 2.5%, 1.4%, and 5.9% respectively.[10]

Changing rates[edit]

Rates of ADHD diagnosis and treatment have increased in both the United Kingdom and the United States since the 1970s. This is believed to be primarily due to changes in how the condition is diagnosed[37] and how readily people are willing to treat it with medications rather than a true change in the frequency.[4] In the UK an estimated 0.5 per 1,000 children had ADHD in the 1970s, while 3 per 1,000 received ADHD medications in the late 1990s. In the UK in 2003, 3.6 percent of male children and less than 1 percent in female children had the diagnosis.[38]: 134 In the United States the number of children with the diagnosis increase from 12 per 1000 in the 1970s to 34 per 1000 in the late 1990s,[38] to 95 per 1,000 in 2007,[39] and 110 per 1,000 in 2011.[40] It is believed that the changes to the diagnostic criteria in 2013 from the DSM 4TR to the DSM 5 will increase the number of people with ADHD especially among adults.[41]

References[edit]

- ^ CDC (2021-01-26). "What is ADHD?". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 2022-09-18.

- ^ CDC (2020-09-21). "Treatment of ADHD | CDC". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 2022-09-18.

- ^ Willcutt EG (July 2012). "The prevalence of DSM-IV attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a meta-analytic review". Neurotherapeutics. 9 (3): 490–9. doi:10.1007/s13311-012-0135-8. PMC 3441936. PMID 22976615.

- ^ a b Cowen P (2012). Shorter Oxford Textbook of Psychiatry (6th ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 546. ISBN 9780191626753. Retrieved 2014-01-17. Cited source of Cowen (2012): Taylor E (2012). "Attention deficit and hyperkinetic disorders in childhood and adolescence". New Oxford Textbook of Psychiatry (2nd ed.). pp. 1644–1654. doi:10.1093/med/9780199696758.003.0215. ISBN 9780199696758.

- ^ Cameron M, Hill P (May 1996). "Hyperkinetic disorder: assessment and treatment". Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 2 (3): 94–102. doi:10.1192/apt.2.3.94. ISSN 1355-5146.

- ^ a b c d e Polanczyk G, de Lima MS, Horta BL, Biederman J, Rohde LA (June 2007). "The worldwide prevalence of ADHD: a systematic review and metaregression analysis". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 164 (6): 942–8. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.164.6.942. PMID 17541055.

- ^ Tsuang M, Tohen M, Jones PB, eds. (2011-03-25). Textbook of psychiatric epidemiology (3rd ed.). Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell. p. 450. ISBN 9780470977408.

- ^ a b c d Ayano G, Yohannes K, Abraha M (2020-03-13). "Epidemiology of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in children and adolescents in Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Annals of General Psychiatry. 19 (1): 21. doi:10.1186/s12991-020-00271-w. PMC 7071561. PMID 32190100.

- ^ a b Song P, Zha M, Yang Q, Zhang Y, Li X, Rudan I (2021-02-11). "The prevalence of adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: A global systematic review and meta-analysis". Journal of Global Health. 11: 04009. doi:10.7189/jogh.11.04009. ISSN 2047-2986. PMC 7916320. PMID 33692893.

- ^ a b c d Fayyad J, Sampson NA, Hwang I, Adamowski T, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Al-Hamzawi A, Andrade LH, Borges G, de Girolamo G, Florescu S, Gureje O, Haro JM, Hu C, Karam EG, Lee S (March 2017). "The descriptive epidemiology of DSM-IV Adult ADHD in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys". Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorders. 9 (1): 47–65. doi:10.1007/s12402-016-0208-3. ISSN 1866-6647. PMC 5325787. PMID 27866355.

- ^ a b A L, Y X, Q Y, L T (2018-08-16). "The Prevalence of Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder among Chinese Children and Adolescents". Scientific Reports. 8 (1): 11169. Bibcode:2018NatSR...811169L. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-29488-2. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 6095841. PMID 30115972.

- ^ a b c Joseph J, Devu B (2019). "Prevalence of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in India: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Indian Journal of Psychiatric Nursing. 16 (2): 118. doi:10.4103/IOPN.IOPN_31_19. ISSN 2231-1505. S2CID 210867045.

- ^ Alhraiwil NJ, Ali A, Househ MS, Al-Shehri AM, El-Metwally AA (2015). "Systematic review of the epidemiology of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in Arab countries". Neurosciences. 20 (2): 137–144. doi:10.17712/nsj.2015.2.20140678. ISSN 1658-3183. PMC 4727626. PMID 25864066.

- ^ Albatti TH, Alhedyan Z, Alnaeim N, Almuhareb A, Alabdulkarim J, Albadia R, Alshahrani K (2017). "Prevalence of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder among primary school-children in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia; 2015–2016". International Journal of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 4 (3): 91–94. doi:10.1016/j.ijpam.2017.02.003. PMC 6372494. PMID 30805508.

- ^ Hakim Shooshtari M, Shariati B, Kamalzadeh L, Naserbakht M, Tayefi B, Taban M (2021-04-30). "The prevalence of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in Iran: An updated systematic review". Medical Journal of the Islamic Republic of Iran. 35: 8. doi:10.47176/mjiri.35.8. PMC 8111633. PMID 33996659.

- ^ Mohammadi M, Ahmadi N, Salmanian M, Arman S, Khoshhal Dastjerdi J, Ghanizadeh A, Alavi A, Malek A, Fathzadeh Gharibeh H, Moharreri F, Hebrani P, Motavallian A (2015). "Psychiatric Disorders in Iranian Children and Adolescents: Application of the Kiddie-sads-present and Lifetime Version (K-sads-pl)". European Psychiatry. 30: 688. doi:10.1016/s0924-9338(15)30544-7. ISSN 0924-9338. S2CID 74259034.

- ^ "Prevalence of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder among Primary School Children in Tikrit City, Iraq". Al-Anbar Medical Journal. 17 (1): 25–29. 2021-06-01. doi:10.33091/AMJ.1101622020. S2CID 242964710.

- ^ Ghossoub E, Ghandour LA, Halabi F, Zeinoun P, Shehab AA, Maalouf FT (2017). "Prevalence and correlates of ADHD among adolescents in a Beirut community sample: results from the BEI-PSY Study". Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health. 11 (1): 20. doi:10.1186/s13034-017-0156-5. ISSN 1753-2000. PMC 5393010. PMID 28428817.

- ^ Bradshaw LG, Kamal M (2017). "Prevalence of ADHD in Qatari School-Age Children". Journal of Attention Disorders. 21 (5): 442–449. doi:10.1177/1087054713517545. ISSN 1087-0547. PMID 24412969. S2CID 23778696.

- ^ "Australia's youth: Mental illness". Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. 25 June 2021. Retrieved 2022-09-16.

- ^ a b "Health of children". Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Retrieved 2022-09-16.

- ^ Lawrence D, Hafekost J, Johnson SE, Saw S, Buckingham WJ, Sawyer MG, Ainley J, Zubrick SR (2016). "Key findings from the second Australian Child and Adolescent Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing". Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 50 (9): 876–886. doi:10.1177/0004867415617836. ISSN 0004-8674. PMID 26644606. S2CID 19863662.

- ^ "Erkennen – Bewerten – Handeln: Zur Gesundheit von Kindern und Jugendlichen in Deutschland" (PDF) (in German). Robert Koch Institute. 27 November 2008. Archived from the original (PDF; 3,27 MB) on 11 December 2013. Retrieved 24 February 2014. – Kapitel 2.8 Aufmerksamkeitsdefizit-/Hyperaktivitätsstörung (ADHS), S. 57 ISBN 978-3-89606-109-6. See also Schlack R, Hölling H, Kurth BM, Huss M (May 2007). "Die Prävalenz der Aufmerksamkeitsdefizit-/Hyperaktivitätsstörung (ADHS) bei Kindern und Jugendlichen in Deutschland" (PDF). Bundesgesundheitsblatt - Gesundheitsforschung - Gesundheitsschutz (in German). 50 (5–6). Robert Koch Institute: 827–35. doi:10.1007/s00103-007-0246-2. PMID 17514469. S2CID 9311463. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 February 2014.

- ^ Catalá-López F, Peiró S, Ridao M, Sanfélix-Gimeno G, Gènova-Maleras R, Catalá MA (October 2012). "Prevalence of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder among children and adolescents in Spain: a systematic review and meta-analysis of epidemiological studies". BMC Psychiatry. 12: 168. doi:10.1186/1471-244X-12-168. PMC 3534011. PMID 23057832.

- ^ a b Young S, Asherson P, Lloyd T, Absoud M, Arif M, Colley WA, Cortese S, Cubbin S, Doyle N, Morua SD, Ferreira-Lay P, Gudjonsson G, Ivens V, Jarvis C, Lewis A (2021). "Failure of Healthcare Provision for Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder in the United Kingdom: A Consensus Statement". Frontiers in Psychiatry. 12: 649399. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2021.649399. ISSN 1664-0640. PMC 8017218. PMID 33815178.

- ^ Ford T, Goodman R, Meltzer H (October 2003). "The British Child and Adolescent Mental Health Survey 1999: The Prevalence of DSM-IV Disorders". Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 42 (10): 1203–1211. doi:10.1097/00004583-200310000-00011. PMID 14560170.

- ^ Sayal K, Ford T, Goodman R (August 2010). "Trends in Recognition of and Service Use for Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in Britain, 1999–2004". Psychiatric Services. 61 (8): 803–810. doi:10.1176/ps.2010.61.8.803. ISSN 1075-2730. PMID 20675839.

- ^ Raman SR, Man KK, Bahmanyar S, Berard A, Bilder S, Boukhris T, Bushnell G, Crystal S, Furu K, KaoYang YH, Karlstad Ø, Kieler H, Kubota K, Lai EC, Martikainen JE (October 2018). "Trends in attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder medication use: a retrospective observational study using population-based databases". The Lancet Psychiatry. 5 (10): 824–835. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30293-1. PMID 30220514. S2CID 52280020.

- ^ "Clearing ADHD caseload could take 5 years, CCG warns". Health Service Journal. 25 January 2019. Retrieved 2 March 2019.

- ^ "CDC – ADHD, Prevalence – NCBDDD". 2017-02-13.

- ^ Rader R, McCauley L, Callen EC (April 2009). "Current strategies in the diagnosis and treatment of childhood attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder". American Family Physician. 79 (8): 657–65. PMID 19405409.

- ^ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (October 17, 2013). "ADHD Home". United States: CDC.gov.

- ^ CDC (March 2004). "Summary Health Statistics for U.S. Children: National Health Interview Survey, 2002" (PDF). Vital and Health Statistics. 10 (221). United States: CDC.

- ^ Staller J, Faraone SV (2006). "Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in girls: epidemiology and management". CNS Drugs. 20 (2): 107–23. doi:10.2165/00023210-200620020-00003. PMID 16478287. S2CID 25835322.

- ^ Anastopoulos AD, Shelton, TL (2001). Assessing attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. New York, NY: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers.

- ^ a b Moffitt TE, Melchior M (June 2007). "Why does the worldwide prevalence of childhood attention deficit hyperactivity disorder matter?". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 164 (6): 856–858. doi:10.1176/ajp.2007.164.6.856. ISSN 0002-953X. PMC 1994964. PMID 17541041.

- ^ "ADHD Throughout the Years" (PDF). Center For Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 2 August 2013.

- ^ a b National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (24 September 2008). "CG72 Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): full guideline" (PDF). NHS.

- ^ "Attention-Deficit / Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD): Data and Statistics". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. May 13, 2013.

- ^ Schwarz A (Mar 31, 2013). "A.D.H.D. Seen in 11% of U.S. Children as Diagnoses Rise". New York Times. Retrieved 2 August 2013.

- ^ Dalsgaard S (February 2013). "Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)". European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 22 (Suppl 1): S43-8. doi:10.1007/s00787-012-0360-z. PMID 23202886. S2CID 23349807.

External links[edit]

Media related to Epidemiology of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Epidemiology of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder at Wikimedia Commons