Shamil Basayev | |

|---|---|

Шамиль Басаев Салман ВоӀ Шамиль Salman Voj Şamil | |

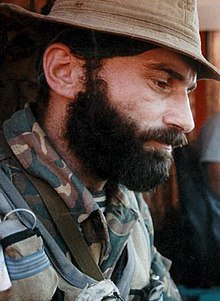

Basayev on the last day of the Budyonnovsk raid on 19 June 1995 | |

| Prime Minister of Ichkeria | |

| In office 1 January 1998 – 3 July 1998 | |

| Preceded by | Aslan Maskhadov |

| Succeeded by | Aslan Maskhadov |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 14 January 1965 Dyshne-Vedeno, Checheno–Ingush ASSR, Russian SFSR, Soviet Union |

| Died | 10 July 2006 (aged 41) Ekazhevo, Ingushetia, Russia |

| Nickname | Abdullah Shamil Abu-Idris |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Years of service | 1991–2006 |

| Rank | Brigadier General |

| Commands | |

| Battles/wars | War in Abkhazia |

Shamil Salmanovich Basayev (Chechen: Салман ВоӀ Шамиль; Salman Voj Şamil; Russian: Шамиль Салманович Басаев; 14 January 1965 – 10 July 2006), also known by his kunya "Abu Idris", was a North Caucasian guerilla leader who served as a senior military commander in the breakaway Chechen Republic of Ichkeria. He held the rank of brigadier general in the Armed Forces of Ichkeria, and was posthumously declared generalissimo. As a military commander in the separatist armed forces of Chechnya, one of his most notable battles was the separatist recapture of Grozny in 1996, which he personally planned and commanded together with Aslan Maskhadov. He also masterminded several of the worst terrorist attacks that occurred in Russia.[1][2]

Starting as a field commander in the Transcaucasus, Basayev led guerrilla campaigns against Russian forces for years, as well as launching mass-hostage takings of civilians, with his goal being the withdrawal of Russian soldiers from Chechnya.[3] From 1997 to 1998, he also served as the vice-prime minister of the breakaway state in Aslan Maskhadov's government. Beginning in 2003, Basayev used the nom de guerre and title of "Emir Abdullah Shamil Abu-Idris". As Basayev's ruthless reputation gained notoriety, he became well revered among his peers and eventually became the highest ranking Chechen military commander and was considered the undisputed leader of the Chechen insurgency as well as being the overall senior leader of all other Chechen rebel factions.

He ordered the Budyonnovsk hospital raid in 1995, the Beslan school siege in 2004,[4] and was responsible for numerous attacks on security forces in and around Chechnya.[5][6][7] He also masterminded the 2002 Moscow theater hostage crisis and the 2004 Russian aircraft bombings. ABC News described him as "one of the most-wanted terrorists in the world".[8] Despite his aura, journalist Tom de Waal described him as "almost unassuming in the flesh", being "of medium height, with a bushy beard and high forehead worthy of a Moscow intellectual, and a quiet voice."[9]

Basayev was killed in a truck explosion during an arms deal in July 2006. Forensic evidence suggests that his death was caused when a landmine he was examining exploded, but Russian officials have also claimed that one of the Kamaz trucks used was booby-trapped and detonated to destroy the arms shipment, also killing Basayev.

Biography[edit]

Family history[edit]

Shamil Basayev was born in the village of Dyshne-Vedeno, near Vedeno, in south-eastern Chechnya, in 1965[10] to Chechen parents from the Belghatoy teip.[11] He was named after Imam Shamil, the third imam of Chechnya and Dagestan and one of the leaders of anti-Russian Chechen-Avar forces in the Caucasian War.

His family is said to have had a long history of involvement in Chechen resistance to foreign occupation, especially Russian rule.

In the 14th century an ancestor fought Timur, a great-great-great-grandfather served as Imam Shamil's deputy and died fighting the Czar, while a great-grandfather died fighting the Bolsheviks.[12] His grandfather fought for the abortive attempt to create a breakaway North Caucasian Emirate after the Russian Revolution.[13]

The Basayevs, along with most of the rest of the Chechen population, had been deported to Kazakhstan during World War II in an act of ethnic cleansing on the orders of the NKVD leader Lavrenti Beria. They were only allowed to return when the deportation order was lifted by Nikita Khrushchev in 1957.

Early life and education[edit]

Basayev, an avid football player, graduated from school in Dyshne-Vedeno in 1982, aged 17, and spent the next two years in the Soviet military serving as a firefighter. For the next four years, he worked at the Aksaiisky state farm in the Volgograd region of southern Russia before moving to Moscow. He reportedly attempted to enroll in the law school of the Moscow State University but failed, and instead entered the Moscow Engineering Institute of Land Management in 1987. However, he was expelled for poor grades in 1988.[14] He subsequently worked as a computer salesman in Moscow, in partnership with a local Chechen businessman, Supyan Taramov.[15] Ironically, the two men ended up on opposite sides in the Chechen wars, during which Taramov sponsored a pro-Russian Chechen militia (Sobaka magazine's dossier on Basayev reported that Taramov apparently equipped or "outfitted" this group of pro-Russian Chechens; they were also known as "Shamil Hunters").

Personal life[edit]

Basayev had four wives, a Chechen woman who was killed in the 1990s, an Abkhaz woman he met while fighting against Georgia, and a Cossack he was said to have married on Valentine's Day, 2005.[16] A fourth secret wife, Elina Ersenoyeva, was apparently forced to marry Basayev under threat of her two brothers' lives, and subsequently hid the identity of her husband from her friends and family.[16] Following revelations about the marriage, Elina was abducted in November 2006, four months after the death of Basayev, allegedly by the Kadyrovtsy ("pro-Kremlin" Chechen forces). She has never been found.[16][17]

In May 1995, eleven members of Basayev's family were killed in a Russian air raid including his mother, his two children and a brother and sister. He also lost his home in the same attack, becoming the first Chechen who took revenge outside Chechen lands, in the Budyonnovsk hospital hostage crisis.[18]

He lost a leg in 2000 during the Second Chechen War.[19]

His younger brother, Shirvani Basayev, who fought the Russians alongside him, is now living in exile in Turkey.[20]

Early militant activities[edit]

When some hardline members of Soviet government attempted to stage a coup d'état in August 1991, Basayev allegedly joined supporters of Russian President Boris Yeltsin on the barricades around the Russian White House in central Moscow, armed with hand grenades.[21]

A few months later, in November 1991, the Chechen nationalist leader Dzhokhar Dudayev unilaterally declared independence from the newly formed Russian Federation. In response, Yeltsin announced a state of emergency and dispatched troops to the border of Chechnya. It was then that Basayev began his long career as an insurgent—seeking to draw international attention to the crisis. Basayev, Lom-Ali Chachayev, and the group's leader, Said-Ali Satuyev, a former airline pilot suffering from schizophrenia,[citation needed] hijacked an Aeroflot Tu-154 plane, en route from Mineralnye Vody in Russia to Ankara on 9 November 1991, and threatened to blow up the aircraft unless the state of emergency was lifted. The hijacking was resolved peacefully in Turkey, with the plane and passengers being allowed to return safely and the hijackers given safe passage back to Chechnya.

Nagorno-Karabakh conflict[edit]

Basayev moved to Azerbaijan in 1992,[22] where he assisted Azerbaijani forces in their unsuccessful war against Armenian fighters in the enclave of Nagorno-Karabakh. He was said to have led a battalion-strength Chechen contingent. According to Azeri Colonel Azer Rustamov, in 1992, "hundreds of Chechen volunteers rendered us invaluable help in these battles led by Shamil Basayev and Salman Raduyev". Basayev was said to be one of the last fighters to leave Shusha (see Capture of Shusha). He ordered the withdrawal of the Chechen detachments from Karabakh in 1993, stating that they had entered the region for a Jihad, but saw not a single sign of it.[23]

Abkhaz–Georgian conflict[edit]

Later in 1992, Basayev traveled to Abkhazia, a breakaway region of Georgia, to assist the local separatist movement against the Georgian government's attempts to regain control of the region. Basayev became the commander-in-chief of the forces of the Confederation of Mountain Peoples of the Caucasus (a volunteer unit of pan-North Caucasian nationalists, people from the North Caucasus). Their involvement was crucial in the Abkhazian war and in October 1993 the Georgian government suffered a decisive military defeat. It was rumored that the volunteers were trained and supplied by some part of the Russian army's GRU military intelligence service. According to The Independent journalist Patrick Cockburn, "cooperation between Mr Basayev and the Russian army is not so surprising as it sounds. In 1992–93 he is widely believed to have received assistance from the GRU when he and his brother Shirvani fought in Abkhazia, a breakaway part of Georgia." No specific evidence was given.[24]

Accusations of being a GRU agent[edit]

The Russian government newspaper Rossiyskaya Gazeta reported that Basayev was an agent of GRU, and another publication by journalist Boris Kagarlitsky said that "It is maintained, for example, that Shamil Basayev and his brother Shirvani are long-standing GRU agents, and that all their activities were agreed, not with the radical Islamists, but with the generals sitting in the military intelligence offices. All the details of the attack by Basayev's detachments were supposedly worked out in the summer of 1999 in a villa in the south of France with the participation of Basayev and the Head of the Presidential administration, Aleksandr Voloshin. Furthermore, it is alleged that the explosive materials used were not supplied from secret bases in Chechnya but from GRU stockpiles near Moscow."[25][26] The Russian newspaper Novaya Gazeta stated that the Basayev brothers "both recruited as agents by the Main Intelligence Directorate of the Russian General Staff (GRU) in 1991–92." The Russian newspaper Versiya published a file from the Russian foreign military agency on Basayev and his brother, which stated that "both Chechen terrorists were named as regular agents of the military intelligence organization."[27] In a July 2020 interview, the former Russian Federal Security Service chief Sergei Stepashin admitted that Basayev cooperated with military intelligence while fighting against Georgian government in Abkhazia.[28]

Russian special forces joined with the Chechens under Basayev to attack Georgia. A GRU agent, Anton Surikov, had extensive connections with Basayev.[29] Russian military intelligence had ordered Basayev to support the Abkhaz.[30]

Basayev received direct military training from the GRU since the Abkhaz were backed by Russia. Other Chechens also were trained by the GRU in warfare, many of these Chechens who fought for the Russians in Abkhazia against Georgia had fought for Azerbaijan against Armenia in the First Nagorno-Karabakh War.[31]

The Russians allowed Basayev to travel between Russia and Abkhazia to battle the Georgians.[32]

In an interview with Nezavisimaya Gazeta on March 12, 1996, Basayev denied the information that he was trained on the basis of the Russian 345th Airborne Regiment: “Not a single Chechen studied there, because they were not accepted.”[33]

Representatives of Chechen separatists have always rejected allegations of Basayev's cooperation with Russian intelligence services, calling them a deliberate attempt to discredit Basayev in the eyes of his supporters.

War crimes[edit]

According to Paul J. Murphy, "Russian military intelligence turned a blind eye to the 1991 terrorist arrest warrant against Basayev to train him and his detachment in Abkhazia, and the Russians even helped direct Basayev's combat operations" and "long after the war, Basayev praised the professionalism and courage of his Russian trainers in Abkhazia – praise that led some of his enemies in Grozny, even President Maskhadov, to later call him a "longtime GRU agent".[34][35]

In 1993 Basayev lead the CMPC corps of North Caucasian volunteers, according to allegations made by Georgian tabloids, the volunteers led by him had decapitated Georgian civilians.[36] After an investigation by a commission composed of Russian deputies, as well as a commission led by UNPO lawyer and investigator Michael van Praag, they could not find any proof for such an incident ever taking place. The tabloid in question also admitted in November that they had no proof to confirm that such an incident had taken place.[37]

Allegations of links with Pakistan's ISI[edit]

Having already been noticed in Afghanistan, where he fought as a young man, and then in Abkhazia in Georgia, Basayev would further attract the attention of Pakistan's premier intelligence agency, the ISI: under Pakistani command, and after meeting many powerful personalities of the army, including the DG ISI Javed Ashraf Qazi, he would be one of the 1,500-strong Afghan mujahideen contingent which fought the Armenians during the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, and in April 1994, the ISI would eventually arrange "a refresher course for Basayev and some of his NCOs in guerrilla warfare and Islamic learning in the Amir Munawid Camp in Khost province in Afghanistan", with Basayev also having further specialized training in Pakistan proper, in cities like Rawalpindi, Peshawar and Muridke, near Lahore. They were also given Stingers, anti-tank rockets and advanced explosives, which would be later used to shoot down Russian combat airplanes and dozens of helicopters. Ultimately, hundreds of Chechens would be trained in Khost, under the ISI as well as the Pakistan-based Islamist outfit Harkat-ul-Ansar, and one of its commanders, Abu Abdullah Jaffa, once in Pakistan's Northern Light Infantry, would work closely with Basayev over the years, as for instance he's supposed to be the one who planned the invasion of Dagestan.[38]

Basayev's own account of his activities in Afghanistan and Pakistan is as such, as given in a September 2003 interview to The Globe and Mail:

I was interested in the Afghan experience on the defence engineering constructions, air defense system and mine-explosive works. Therefore, I went first to Peshawar (Pakistan). There, I lived with some Tajiks and through them I agreed for training for 200 Chechens. I sold at home some captured weaponry, seized in June from Labazanov’s band in then Groznyi, took also some money from my acquaintances and transported the first group of 12 people to Afghanistan. There I spent a night in the training camp and in the morning I returned to Karachi to meet the second group. But at the airport they aroused a suspicion because of their number and they didn’t have their passports in their hands. The Russians raised a large noise and in the week they sent us back.[39]

Basayev's role in the First Chechen War[edit]

- 1994–1995

The First Chechen War began when Russian forces invaded Chechnya on 11 December 1994, to depose the government of Dzhokhar Dudayev. With the outbreak of war, Dudayev made Basayev one of the front-line commanders. Basayev took an active role in the resistance, successfully commanding his "Abkhaz Battalion." The unit inflicted major losses on Russian forces in the Battle of Grozny, Chechnya's capital, which lasted from December 1994 to February 1995. Basayev's men were among the last fighters to abandon the city.

- 1995

After capturing Grozny, the momentum changed in favor of the Russian forces, and by April Chechen forces had been pushed into the mountains with most of their equipment destroyed. Basayev's "Abkhaz Battalion" suffered many casualties, particularly during battles around Vedeno in May and their ranks sank to as low as 200 men, critically low on supplies.

Around this time, Basayev also suffered a personal tragedy. On 3 June 1995, during a Russian air raid on Basayev's hometown of Dyshne-Vedeno, two bombs targeted the home of Basayev's uncle, killing six children, four women as well as his uncle. Basayev's wife, child and his sister Zinaida were among the dead. Twelve additional members of Basayev's family were also seriously wounded in the attack.[40] One of his brothers was also killed in fighting near Vedeno.

In an attempt to force a stop to the Russian advance, some Chechen forces resorted to a series of attacks directed against civilian targets outside the area that they claimed. Basayev led the most infamous such attack, the Budyonnovsk hospital hostage crisis on 14 June 1995, less than two weeks after he lost his family in the air raids. Basayev's large band seized the Budyonnovsk hospital in southern Russia and the 1,600 people inside for a period of several days. At least 129 civilians died and 415 were wounded during the crisis as the Russian special forces repeatedly attempted to free the hostages by force. Although Basayev failed in his principal demand for the removal of Russian forces from Chechnya, he did successfully negotiate a stop to the Russian advance and an initiation of peace talks with the Russian government, saving the Chechen resistance by giving them time to regroup and recover. Basayev and his fighters then returned to Chechnya under cover of human shields.

On 23 November, Basayev announced on the Russian NTV television channel, that four cases of radioactive material had been hidden around Moscow. Russian emergency teams roamed the city with Geiger counters, and located several canisters of caesium, which had been stolen from the Budennovsk hospital by the Chechen militants. The incident has been called "the most important sub-state use of radiological material."[41]

- 1996

By 1996 Basayev had been promoted to the rank of General and Commander of the Chechen Armed Forces. In July 1996 he was implicated in the death of the rogue Chechen warlord Ruslan Labazanov.[citation needed]

In August 1996, he led a successful operation to retake the Chechen capital Grozny, defeating the Russian garrison of the city.[42] Yeltsin's government finally moved for peace, bringing in former Soviet–Afghan War General Aleksandr Lebed as a negotiator. A peace agreement was concluded between the Chechens and Russians, under which the Chechens acquired de facto independence from Russia.

Interwar period[edit]

Basayev stepped down from his military position in December 1996 to run for president in Chechnya's second (and the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria's first and only ever internationally monitored) presidential elections. Basayev came in second place to Aslan Maskhadov, obtaining 23.5% of the votes. Allegedly Basayev found the defeat very painful.[citation needed]

In early 1997 he was appointed deputy Prime Minister of Chechnya by Maskhadov. He briefly served as acting leader of Chechnya during President Maskhadov's trip to the Middle East in 1997.[43] In January 1998 he became the acting head of the Chechen government for a six-month term, after which he resigned. Basayev's appointment was symbolic because it took place on the eve of the celebrations of the 200th anniversary of his renowned namesake. Basayev subsequently reduced the government's administrative departments and abolished several ministries. However, the collection of taxes and the Chechen National Bank's reserves shrank, and theft of petroleum products increased seriously.

Maskhadov worked with Basayev until 1998, when Basayev established a network of military officers, who soon became rival warlords. As Chechnya collapsed into chaos, Basayev's reputation began to plummet as he and others were accused of corruption and involvement in kidnapping; his alliance with Khattab also alienated many Chechens. By early 1998 Basayev emerged as the main political opponent of the Chechen president, who in his opinion was "pushing the republic back to the Russian Federation." On 31 March 1998, Basayev called for the termination of talks with Russia; on 7 July 1998, he sent a letter of resignation from his post as the Chechen Prime Minister. During these years he wrote Book of a Mujahiddeen, an Islamic guerilla manual.

Incursion into Dagestan[edit]

In December 1997, after Movladi Udugov's Islamic Nation party had called for Chechnya to annex territories in neighbouring Dagestan, Basayev promised to "liberate" neighbouring Dagestan from its status as "a Russian colony."[44]

According to Alex Goldfarb and Marina Litvinenko's book Death of a Dissident, Kremlin-critic Boris Berezovsky said that he had a conversation with the Chechen Islamist leader Movladi Udugov in 1999, six months before the beginning of fighting in Dagestan.[45] A transcript of the phone conversation between Berezovsky and Udugov was leaked to one of Moscow tabloids on 10 September 1999.[46] Udugov proposed to start the Dagestan war to provoke the Russian response, topple the Chechen president Aslan Maskhadov and establish new Islamic republic of Basayev-Udugov that would be friendly to Russia. Berezovsky asserted that he refused the offer, but "Udugov and Basayev conspired with Stepashin and Putin to provoke a war to topple Maskhadov ... but the agreement was for the Russian army to stop at the Terek River. However, Putin double-crossed the Chechens and started an all-out war."[45]

It was also alleged that Alexander Voloshin, a key figure in the Yeltsin administration, paid Basayev to stage the Dagestan incursion,[47] and that Basayev was working for the Russian GRU at the time.[48][49][50] According to the BBC, conspiracy theories are part of the staple diet of Moscow politics.[51]

In August 1999, Basayev and Khattab led a 1,400-strong group of militants in an unsuccessful attempt to aid Dagestani Wahhabists to take over the neighboring Republic of Dagestan and establish an Islamic republic and start an uprising. By the end of the month, Russian forces had managed to repel the invasion.

1999 apartment bombings[edit]

In early September, a series of bombings of Russian apartment blocks took place, killing 293 people. Russia quickly blamed the attacks on Chechen militants without any evidence.[52] Basayev, Ibn Al-Khattab and Achemez Gochiyaev were named by Russia as key suspects. Basayev and Khattab denied any involvement in the attacks, with Basayev stating whoever committed them are not human.[51][53] According to a Russian FSB spokesman, Gochiyaev's group was trained at Chechen militant bases in the towns of Serzhen-Yurt and Urus-Martan, where the explosives were prepared. The group's "technical instructors" were two Arab field commanders, Abu Umar and Abu Djafar, and Al-Khattab was the bombings' brainchild.[54] Two members of Gochiyayev's group that carried out the attacks, Adam Dekkushev and Yusuf Crymshamhalov, have been sentenced to life term each in a special-regime colony.[55] According to FSB, Basayev and Al-Khattab masterminded the attacks.[56] Al-Khattab has been killed, but Gochiyaev remains a fugitive.

Although Basayev and Khattab denied responsibility, the Russian government blamed the Chechen government for allowing Basayev to use Chechnya as a base. Chechen President Aslan Maskhadov denied any involvement in the attacks, and offered a crackdown on the renegade warlords, which Russia refused. Commenting on the attacks, Shamil Basayev said: "The latest blast in Moscow is not our work, but the work of the Dagestanis. Russia has been openly terrorizing Dagestan, it encircled three villages in the centre of Dagestan, did not allow women and children to leave."[51] Al-Khattab, who was reportedly close with Basayev, said the attacks were a response to what the Russians had done in Karamakhi and Chabanmakhi, two Dagestani villages where followers of the Wahhabi sect were living until the Russian army bombed them out.[57] A group called the Liberation army of Dagestan claimed responsibility for the apartment bombings.[57][58][59][60]

Second Chechen War[edit]

Michael Radu of the Foreign Policy Research Institute said "Basayev managed to radically change the world's perception of the Chechen cause, from that of a small nation resisting victimization by Russian imperialism into another outpost of the global jihad. In the process, he also significantly modified the very nature of Islam in Chechnya and Northern Caucasus, from a traditional mix of syncretism and Sufism into one strongly influenced by Wahhabism and Salafism—especially among the youth. With Wahhabism came expansionism."[61]

- 1999

Basayev stayed in Grozny for the duration of the siege of the city. His threats of "kamikaze" attacks in Russia were widely dismissed as a bluff.[citation needed]

- 2000

During the Chechens retreat from Grozny in January 2000 Basayev lost a foot after stepping on a land mine while leading his men through a minefield. The operation to amputate his foot and part of his leg was videotaped by Adam Tepsurgayev and later televised by Russia's NTV network and Reuters, showing his foot being removed by Khassan Baiev[62] using a local anaesthetic while Basayev watched impassively.

Despite this injury, Basayev eluded Russian capture together with other Chechens by hiding in forests and mountains. He welcomed assistance from foreign fighters from Afghanistan and other Islamic countries, encouraging them to join the Chechen cause. He also ordered the execution of nine Russian OMON prisoners on 4 April 2000; the men were killed because the Russians had refused to swap them for Yuri Budanov, an arrested army officer accused of raping and killing an 18-year-old Chechen girl.[63]

- 2001

According to the US State Department, Basayev trained in Afghanistan in 2001. The US also alleges that Basayev and Khattab sent Chechens to serve in Al-Qaeda's "055" brigade, fighting alongside the Taliban against the Northern Alliance in Afghanistan.[64]

On 2 June 2001, it was reported General Gennady Troshev, then-commander-in-chief of Russian forces in Chechnya, had offered a bounty of one million dollars to anyone who would bring him the head of Basayev.

In August, Basayev commanded a large-scale raid on the Vedensky District. A deputy commander of Russian forces in Chechnya claimed Basayev was wounded in a firefight.[65]

- 2002

In January 2002, Basayev's father, Salman, was reputedly killed by Russian forces.[66] This has not been independently confirmed. Shamil's younger brother, Shirvani, was reported killed by the Russians in 2000, but is, according to numerous accounts, actually living in exile in Turkey where he is involved in coordination of the activities of the diaspora.[citation needed]

In May, the Russian side declared Basayev "dead".The Russian military had also made several claims about Basayev's alleged death in the past.[67][better source needed]

Around 2 November 2002, Basayev claimed on a militant website that he was responsible for the Moscow theater hostage crisis (although the siege was led by Movsar Barayev) in which 50 Chechens held about 800 people hostage; Russian forces later stormed the building using gas, killing the Chechens and more than 100 hostages. Basayev also tendered his resignation from all posts in Maskhadov's government apart from the reconnaissance and sabotage battalion. He defended the operation but asked Maskhadov for forgiveness for not informing him of it. [citation needed] The answer to who was behind the hostage taking, however, is not so clear – some dissidents claim, including Alexander Litvinenko, was that the FSB was behind the Moscow theater incident.

On 27 December 2002, Chechen suicide bombers rammed vehicles into the republic's government headquarters in Grozny, bringing down the four-story building and killing about 80 people. Basayev claimed responsibility, published the video of the attack, and said he personally triggered the bombs by remote control.[68]

- 2003

On 12 May 2003, suicide bombers rammed a truck loaded with explosives into a Russian government compound in Znamenskoye, northern Chechnya, killing 59 people. Two days later a woman got within six feet of Akhmad Kadyrov, the head of the Moscow-appointed Chechen administration, and blew herself up killing herself and 14 people; Kadyrov was unhurt. Basayev claimed responsibility for both attacks; Maskhadov denounced them.

From June until August 2003 Basayev lived in the town of Baksan in nearby Kabardino-Balkaria. Eventually, a skirmish took place between when local policemen came to check the house he was staying in. Basayev escaped the incident.[69]

On 8 August 2003, U.S. Secretary of State Colin Powell designated Shamil Basayev as a threat to U.S. security and citizens, saying that Basayev "has committed or poses a significant risk of committing, acts of terrorism that threaten the security of U.S. nationals or the national security, foreign policy, or economy of the United States".[70] In February, the U.S. State Department designated three Chechen groups with links to al-Qaeda, including the Islamic International Peacekeeping Brigade, stating that Osama bin-Laden had sent "substantial" amounts to its founders Basayev and Ibn al-Khattab.[71] The United Nations Security Council also placed Basayev on its official list of terrorists after the U.S. designation.[2]

In late 2003, Basayev claimed responsibility for terrorist bombings in both Moscow and Yessentuki in Stavropol Krai. He said both attacks were carried out by the group operating under his command.[72]

- 2004

On 9 May 2004, the pro-Russian Chechen President Akhmad Kadyrov was killed in Grozny in a bomb attack for which Basayev later claimed responsibility. That explosion killed at least six people and wounded nearly 60, including the top Russian military commander in Chechnya, who lost his leg; Basayev called it a "small but important victory".

Basayev was accused of commanding the 21 June raid on Nazran in the Russian republic of Ingushetia. In fact, he was shown in a video made of the raid, in which he led a large group of militants. Around 90 people died in this attack, mostly local servicemen and officials of the Russian security forces including the republic's acting interior minister. The Ministry building was burned down.

In September 2004 Basayev claimed responsibility for the Beslan school siege in which over 350 people, most of them children, were killed and hundreds more injured.[4] The Russian government put up a bounty of 300m rubles ($10m) for information leading to his capture.[73] Basayev himself did not participate in the seizure of the school, but claimed to have organized and financed the attack, boasting that the whole operation cost only 8,000 euros. On 17 September 2004, Basayev issued a statement claiming responsibility for the school siege, saying his Riyadus-Salihiin "Martyr Battalion" had carried out this and other attacks. In his message, Basayev described the Beslan massacre as a "terrible tragedy". He blamed it on Russian President Vladimir Putin, stating that by Putin giving the order to storm the school he had destroyed and injured the hostages.[74][75]

Basayev also claimed responsibility for the attacks against civilians during the previous week, in which a metro station in Moscow was bombed (killing 10 people), and two airliners were blown up by suicide bombers (killing 89 people).[4] Basayev dubbed these attacks "Operation Boomerang". He also said that during the Beslan crisis he offered Putin "independence in exchange for security".[76]

- 2005

On 3 February 2005, UK's Channel 4 announced that it would air Basayev's interview. In response, the Russian Foreign Ministry said that the broadcast could aid terrorists in achieving their goals and demanded that the Government of the United Kingdom call off the broadcast. The British Foreign Office replied that it could not intervene in the affairs of a private TV channel and the interview was aired as scheduled.[77] The same day, Russian media reported that Shamil Basayev had been killed;[78] it was the sixth such report about Basayev's demise since 1999.[78]

In May 2005, Basayev reportedly claimed responsibility for the power outage in Moscow.[79] The BBC reported that the claim for responsibility was made on a web site connected to Basayev, but conflicted with official reports that sabotage was not involved.

Even though Basayev had a $10 million bounty on his head, he gave an interview to Russian journalist Andrei Babitsky in which he described himself as "a bad guy, a bandit, a terrorist ... but what would you call them?", referring to his enemies. Basayev stated each Russian had to feel war's impact before the Chechen war would stop. Basayev asked "Officially, over 40,000 of our children have been killed and tens of thousands mutilated. Is anyone saying anything about that? ... responsibility is with the whole Russian nation, which through its silent approval gives a 'yes'."[80] This interview was broadcast on U.S. television network ABC's Nightline program, to the protest of the Russian government; on 2 August 2005, Moscow banned journalists of the ABC network from working in Russia.[81]

On 23 August 2005, Basayev rejoined the Chechen separatist government, taking the post of first deputy chairman.[82] Later this year Basayev claimed responsibility for a raid on Nalchik, the capital of the Russian republic of Kabardino-Balkaria. The raid occurred on 13 October 2005; Basayev said that he and his "main units" were only in the city for two hours and then left. There were reports that he had died during the raid, but this was contradicted when the separatist website, Kavkaz Center, posted a letter from him.[citation needed]

- 2006

In March 2006, Prime Minister of Chechen Republic, Ramzan Kadyrov, claimed that upwards of 3,000 police officers were hunting for Basayev in the southern mountains.[83] On 15 June 2006, Basayev repeated his claim of responsibility for the bombing that killed Akhmad Kadyrov, saying he had paid $50,000 to those who carried out the assassination. He also said he had put a $25,000 bounty on the head of Ramzan, mocking the young Kadyrov in offering the smaller bounty.[citation needed]

On 27 June 2006, Shamil Basayev was appointed by Dokka Umarov as the Vice President of Ichkeria. On 10 July 2006, in his last statement at 1.06 pm Moscow time, Kavkaz Center quoted him as thanking the Mujahideen Shura Council for executing the three captured Russian diplomats in Iraq and calling it "a worthy answer to the murder by Russian terrorists from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation of the Chechen diplomat, ex-president of CRI, Zelimkhan Yandarbiyev".[citation needed]

Death[edit]

On 10 July 2006, Basayev was killed near the border of North Ossetia in the village of Ekazhevo, Ingushetia, a republic bordering Chechnya.[84]

According to the Interior Ministry and Prosecutor of Ingushetia, a group of three cars and two KAMAZ trucks (one pulling the other by a rope) gathered at the spot of an unfinished estate on the outskirts of the village in the early morning hours of 10 July.[85] According to a handful of witnesses, men in black uniforms came in and out from the wooded area adjacent to the estate that runs to the border of North Ossetia; the men were carrying boxes, shifting them from one vehicle to another, when a massive explosion occurred.[85]

It is believed that the partially completed estate, which contained empty new buildings, was being used as an insurgent reception and distribution point for large quantities of weapons purchased from abroad.[85] It is also believed that the most "anticipated" part of the incoming shipment was located in the KAMAZ trucks, but because one of them broke down the weaponry had to quickly be transferred into the cars.[85]

Basayev is assumed to have been the main recipient of the arms, and thus in charge of distributing them. With the back tailgate of one of the trucks open, Basayev allegedly asked that a mine be placed on the ground for inspection, at which point it exploded.[85] An Ossetian forensic specialist who examined Basayev's remains stated that, "The man…died of mine-blast injuries. The explosive device was quite powerful…and the victim was in close proximity to the epicenter. Most likely, the bomb lay on the ground, and the victim was bending over it."[85]

According to explosives experts, Basayev was most likely a victim of careless handling of the mine, but it is also not out of the question that the FSB could have been involved – as they would claim in the aftermath of the detonation.[85] This could have happened if the shipment of weapons was seized and the smugglers detained; in forcing the captured smugglers to cooperate, an ordinary-looking anti-personnel mine rigged with an extra-sensitive fuse or radio-controlled detonator could have been inserted amongst the cargo.[85] The device almost certainly would have caused suspicion when discovered in the shipment, which might explain why Basayev stopped to inspect it, at that point triggering the explosion.[85] It was also not ruled out that an unknown FSB operative set off the blast by remote control, but in the event that this was the case, it almost assuredly would not have been a "targeted" killing, as identifying Basayev in the dark – even with the aid of night-vision goggles – would have been exceedingly difficult.[85] Thus, experts have concluded that if it was a remote-controlled blast, it was intended to eliminate the weapons shipment and whoever the recipients were, rather than specifically Basayev.[85]

Basayev's upper torso was recovered at the epicenter of the blast, while smaller pieces of his remains were scattered over the distance of a mile.[85] Included among the smaller pieces was Basayev's prosthetic lower right leg, which led FSB Director Nikolai Patrushev to confidently assert that Basayev was dead even before positive identification.[85]

Russian officials stated that the explosion was the result of a special targeted killing operation. According to the official version of Basayev's death, the FSB, following him with a drone, spotted his car approach a truck laden with explosives that the FSB had prepared, and by remote control triggered a detonator that the FSB had hidden in the explosives.[84][86][87]

Interfax, quoting Ingush Deputy Prime Minister Bashir Aushev, reported that the explosion was a result of a truck bomb detonated next to the convoy by Russian agents.[88] According to a Russian edition of Newsweek,[89] Basayev's death was a result of an FSB operation, whose primary aim was to prevent a planned terrorist attack in Chechnya or Ingushetia the days before the G8 summit in St Petersburg. The Russian ambassador to the UN, Vitaly Churkin, said: "He is a notorious terrorist, and we have very clearly and publicly announced what is going to happen to notorious terrorists who commit heinous crimes of the type Mr. Basayev has been involved in."[90] In February 2014, a Turkish court convicted a Chechen national Ruslan Papaskiri aka Temur Makhauri with the killings of several Chechen separatists on Turkish soil. The pro-Chechen separatist Imkander organization held a press conference claiming that Turkish investigators believed that Makhauri had prepared the explosives laden truck that killed Basayev.[91]

On 29 December 2006, forensic experts positively identified Basayev's remains.[92] On 6 October 2007, Basayev was promoted to the rank of Generalissimo post mortem by Doku Umarov.[93]

Book of a Mujahideen[edit]

Basayev wrote a book after the First Chechen War, Book of a Mujahideen. According to the introduction, in March 2003 Basayev obtained a copy of The Manual of the Warrior of Light by Paulo Coelho. He wanted to draw benefits to the Mujahideen from this book and decided to "rewrite most of it, remove some excesses and strengthen all of it with verses (ayats), hadiths and stories from the lives of the disciples." Some sections are specifically about ambush tactics, etc.[94]

In popular culture[edit]

Basayev appeared in 2018 Russian movie Decision: Liquidation, played by Ayub Tsingiev.[95]

References[edit]

- ^ "Chechen Rebel Leader Basayev Killed in Blast". pbs.org. 10 July 2006.

- ^ a b "Obituary: Shamil Basayev". BBC News. 10 July 2006.

- ^ Jonathan Steele (11 July 2006). "Shamil Basayev -Chechen politician seeking independence through terrorism". Obituary. London.

one-time guerrilla commander who turned into a mastermind of spectacular and brutal terrorist actions ... served for several months as prime minister

- ^ a b c "Chechen warlord behind Russian school siege". ABC News. 17 September 2004. Archived from the original on 19 September 2004.

- ^ "Russia's tactics make Chechen war spread across Caucasus". Kavkaz. 16 September 2005. Archived from the original on 1 January 2014. Retrieved 4 November 2010.

- ^ "Russia: RFE/RL Interviews Chechen Field Commander Umarov". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 28 July 2005. Retrieved 4 November 2010.

- ^ No Terrorist Acts in Russia Since Beslan: Whom to Thank? Archived 18 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Chechen Guerilla Leader Calls Russians 'Terrorists'". ABC News. 28 July 2005. Retrieved 30 March 2010.

- ^ "Shamil Basayev: Chechen warlord" (30 September 1999), BBC News. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- ^ Wilhelmsen, Julie (January 2005). "Between a Rock and a Hard Place: The Islamisation of the Chechen Separatist Movement" (PDF). Europe-Asia Studies. 57 (1): 35–59. doi:10.1080/0966813052000314101. S2CID 153594637. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 April 2014. Retrieved 30 December 2012.

- ^ "Ведено". Archived from the original on 10 November 2020. Retrieved 10 November 2020.

- ^ Boudreaux, Richard (22 January 1995). "Chechnya's Mountain Men Say They'll Vanquish Russia". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Chechen separatist who battled hard for his country.[dead link]

- ^ "Basaev Shamil (1965–2006)". universalis.fr.

- ^ ""Мне не дали поймать Хаттаба и Басаева"". kommersant.ru. 13 February 2001.

- ^ a b c C. J. Chivers (27 August 2008). "Missing Chechen Was Secret Bride of Terror Leader". The New York Times.

- ^ "Chechen woman abducted looking for missing daughter". One India. Grozny. Reuters. 13 October 2006. Archived from the original on 14 May 2013. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

- ^ Boudreaux, Richard. "Hostages in Russia's Heartland: Defiance of Russians Flows in the Veins of Lead Hostage-Taker: Guerrilla: Shamil Basayev's family has long fought invaders. But the killings of his mother and 2 children preceded his raid on a city outside Chechnya". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 3 December 2020.

- ^ Steve Rosenberg. "Operating on the enemy in the two Chechen wars". BBC. Retrieved 3 December 2020.

- ^ Fuller, Liz (8 July 2016). "Chechen Leader Demands Turkey Hand Over 'Terrorists'". RFERL.

- ^ The Wolves of Islam: Russia and the Faces of Chechen Terror by Paul J. Murphy, Brassey's Inc. p. 9

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: "Samil Basayev Qarabağ haqqında..." YouTube.

- ^ "ШамилЬ Басевв Заявил, Что Армяне Были Лучше Подготовлены В Карабахской Войне" [Shamil Basaev Stated That The Armenians Were Better Prepared in the Karabakh War]. PanARMENIAN.Net. 24 July 2000. Retrieved 25 June 2023.

- ^ Russia 'planned Chechen war before bombings' Archived 27 August 2009 at the Wayback Machine 29 January 2009 The Independent

- ^ Anne Aldis (2000). The second Chechen War. Strategic and Combat Studies Institute (in association with Conflict Studies Research Centre). p. 18. ISBN 1-874346-32-1. Retrieved 14 August 2011.

- ^ Paul J. Murphy (2004). The wolves of Islam: Russia and the faces of Chechen terror (illustrated ed.). Brassey's. p. 107. ISBN 1-57488-830-7. Retrieved 14 August 2011.

- ^ Boris Kagarlitsky (2002). Russia under Yeltsin and Putin: neo-liberal autocracy (illustrated ed.). Pluto Press. p. 234. ISBN 0-7453-1507-0. Retrieved 14 August 2011.

- ^ "Ex-FSB Head Says Shamyl Basayev Cooperated with Russian Intelligence in Abkhazia". Civil Georgia. 14 July 2020. Retrieved 16 July 2020.

- ^ Boris Kagarlitsky (2002). Russia under Yeltsin and Putin: neo-liberal autocracy (illustrated ed.). Pluto Press. p. 229. ISBN 0-7453-1507-0. Retrieved 14 August 2011.

- ^ Library Information and Research Service (2006). The Middle East, abstracts and index, Part 4. Northumberland Press. p. 608. Retrieved 14 August 2011.

- ^ Yossef Bodansky (2008). Chechen Jihad: Al Qaeda's Training Ground and the Next Wave of Terror (reprint ed.). HarperCollins. p. 36. ISBN 978-0-06-142977-4. Retrieved 14 August 2011.

- ^ Svante E. Cornell; S. Frederick Starr (2009). Svante E. Cornell, S. Frederick Starr (ed.). The guns of August 2008: Russia's war in Georgia (illustrated ed.). M.E. Sharpe. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-7656-2508-3. Retrieved 14 August 2011.

- ^ Олег Блоцкий (12 March 1996). "Шамиль Басаев". Archived from the original on 29 March 2017. Retrieved 29 March 2017.

- ^ Paul J. Murphy (2004). The wolves of Islam: Russia and the faces of Chechen terror (illustrated ed.). Brassey's. p. 15. ISBN 1-57488-830-7.

- ^ Stanislav Lunev (26 January 1996). "The Specter of Terror Begins to Haunt Russia". Prism. Vol. 2, no. 2. Retrieved 15 August 2011.

- ^ Yossef Bodansky (2008). Chechen Jihad: Al Qaeda's Training Ground and the Next Wave of Terror (reprint ed.). HarperCollins. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-06-142977-4. Retrieved 14 August 2011.

- ^ "Четверть века назад: Гагрская битва". Эхо Кавказа (in Russian). 6 October 2017. Retrieved 14 December 2022.

- ^ Hein Kiessling, Faith, Unity, Discipline: The Inter-Service-Intelligence (ISI) of Pakistan, Oxford University Press (2016), pp. 126–127

- ^ Williams, Brian Glyn (2007). "Allah's foot soldiers: an assessment of the role of foreign fighters and Al-Qa'ida in the Chechen insurgency". In Gammer, Moshe (ed.). Ethno-Nationalism, Islam and the State in the Caucasus: Post-Soviet Disorder. Routledge. p. 170.

- ^ The Wolves of Islam: Russia and the Faces of Chechen Terror by Paul J. Murphy, Brassey's Inc. Page 20

- ^ Richard Sakwa, ed. (2005). "Western views of the Chechen Conflict". Chechnya: From Past to Future. Anthem Press. p. 235. ISBN 978-1-84331-165-2.

- ^ "The day I met the terrorist mastermind". The Sunday Times. 4 September 2004. Archived from the original on 23 May 2011. Retrieved 29 July 2011.

- ^ "Russia Likely to be Upset by Acting Chechen Leader". Greensboro. 5 April 1997. Retrieved 10 February 2023.

- ^ "Chechnya repeats territorial claims on Dagestan". Fplib. December 1997. Archived from the original on 26 July 2011. Retrieved 4 November 2010.

- ^ a b Alex Goldfarb, with Marina Litvinenko Death of a Dissident: The Poisoning of Alexander Litvinenko and the Return of the KGB, The Free Press, 2007, ISBN 1-4165-5165-4, p. 216.

- ^ "Death of a Dissident", p. 189.

- ^ "'The Operation "Successor"' (in Russian)". Lib. Retrieved 4 November 2010.

- ^ Western leaders betray Aslan Maskhadov Archived 14 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Chechen Parliamentary Speaker: Basayev was G.R.U. Officer, The Jamestown Foundation". Archived from the original on 16 October 2006.

- ^ Fuller, Liz (1 March 2005). "'Analysis: Has Chechnya's Strongman Signed His Own Death Warrant?'". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Retrieved 4 November 2010.

- ^ a b c "Russia's bombs: Who is to blame?". BBC News. 30 September 1999. Retrieved 4 November 2010.

- ^ "How the 1999 Russian apartment bombings led to Putin's rise to power". Insider. Retrieved 28 January 2023.

- ^ Akhmadov, Ilyas; Lanskoy, Miriam. The Chechen Struggle: Independence won and Lost. p. 162.

- ^ Russia: The FSB Vows to Capture the Remaining Co-Conspirators Archived 29 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine IPR Strategic Business Information Database. 13 January 2004

- ^ "Apartment houses-blasts defendants sentenced to life imprisonment". Russiajournal.com. Archived from the original on 22 November 2008. Retrieved 4 November 2010.

- ^ "Alleged suspect for 1999 bombings hiding in Georgia: Russian FSB". Terror 99. Archived from the original on 23 October 2002. Retrieved 4 November 2010.

- ^ a b Womack, Helen (19 September 1999). "Russia caught in sect's web of terror". The Independent. London. Retrieved 4 November 2010.

- ^ "Dr Mark Smith, A Russian Chronology July 1999 – September 1999" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 March 2009. Retrieved 4 November 2010.

- ^ А. Новосельская; С. Никитина; М. Бронзова (10 September 1999). "Взрыв жилого дома в Москве положил конец спокойствию в столице". NG. Retrieved 4 November 2010.

- ^ Sileen Hunter; Jeffrey L. Thomas; Alexander Melikishvili; J. Collins (2004). Islam in Russia: The Politics of Identity and Security. M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 978-0-7656-1283-0.

- ^ Radu, Michael. "Shamil Basayev: Death of a Terrorist Archived 7 November 2006 at the Wayback Machine." Foreign Policy Research Institute. 14 July 2006. Retrieved 31 October 2011.

- ^ Khassan Baiev, Ruth Daniloff. The Oath: A Surgeon Under Fire. Walker & Company. 2004. ISBN 0-8027-1404-8. (Khassan Baiev is a surgeon who amputated leg of Shamil Basayev after his injury on a mine field and operated on Salman Raduev and Arbi Barayev himself. However, Barayev promised to kill Baiev because he always also helped wounded Russian soldiers if necessary).

- ^ Cockburn, Patrick (6 April 2000). "Chechen fighters kill nine captured Russian soldiers – Europe, World". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 8 September 2009. Retrieved 19 October 2010.

- ^ Richard Sakwa, ed. (2005). "Globalization, 'New Wars', and the War in Chechnya". Chechnya: From Past to Future. Anthem Press. pp. 208–209. ISBN 978-1-84331-165-2.

- ^ Wines, Michael (23 August 2001). "Chechnya: Rebel Said To Be Wounded". The New York Times. Russia; Chechnya (Russia). Retrieved 4 November 2010.

- ^ "Shamil Basayev's father was killed in Chechnya". Watchdog.cz. Retrieved 4 November 2010.

- ^ Tavernise, Sabrina (1 May 2002). "Chechen Declared Dead, May 1, 2002". The New York Times. Russia; Chechnya (Russia). Retrieved 4 November 2010.

- ^ "Shamil Basayev". The Daily Telegraph. London. 11 July 2006. Retrieved 4 November 2010.

- ^ Orazayeva, Luiza (5 August 2004). "Basayev hided in Kabardino-Balkaria for two months". Caucasian Knot. Retrieved 28 January 2023.

- ^ "U.S. names Chechen leader a security threat". cnn.com. 8 August 2003.

- ^ "U.S. puts 3 Chechen groups on terrorist list". cnn.com. 28 February 2003.

- ^ "Unknown rebel group claims Moscow metro blast, March 2, 2004". Gazeta.ru. 14 September 2004. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 4 November 2010.

- ^ "Russian-Chechen War Turns into Bounty Race". The Moscow News. 10 September 2004.

- ^ "Putin: Western governments soft on terror". American Foreign Policy Council. 17 September 2004. Archived from the original on 23 February 2008.

- ^ "Chechen claims Beslan attack". CNN. 17 September 2004.

- ^ "Excerpts: Basayev claims Beslan". BBC News. 17 September 2004.

- ^ "Another Beslan?". Channel 4. 3 February 2005.

- ^ a b "Basaev Didn't Save Face". Kommersant. 11 July 2006. Archived from the original on 21 July 2006.

- ^ "Basayev claims Moscow power cut". BBC News. 27 May 2005.

- ^ "Chechen Guerilla Leader Calls Russians 'Terrorists' / Mastermind of Beslan School Massacre Vows to Fight for Chechen Freedom". ABC News. 29 July 2005.

- ^ "Russia: Moscow Says It Will Punish U.S. TV Network Over Basaev Interview". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 3 August 2005.

- ^ "Time to get tough on Chechen government-in-exile, September 2, 2005". Charlestannock.com. 2 September 2005. Archived from the original on 21 March 2017. Retrieved 4 November 2010.

- ^ "Thousands of Police Hunt for Basayev in Mountains". The Moscow Times. 13 March 2006. Archived from the original on 21 May 2006.

- ^ a b "Боевики, подорвавшиеся на собственной взрывчатке, планировали провести теракт". 1TV. 10 July 2006. Archived from the original on 18 October 2015. Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "Шамиля Басаева узнают по рукам и ноге". Коммерсанть. 12 July 2006. Archived from the original on 9 August 2011. Retrieved 29 July 2011.

- ^ "Mastermind of Russian school siege killed; Report: Chechen warlord dies in blast set by Russian agents". CNN. 10 July 2006. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- ^ Ликвидация с вариациями. Russian Newsweek (in Russian). 23 July 2006. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007.

- ^ "Mastermind of Russian school siege killed – 10 July 2006". CNN. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- ^ "Ликвидация с вариациями (in Russian)". Russian Newsweek. 23 July 2006. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007.

- ^ Benny Avni (13 July 2006). "Qatar Presents New Resolution on Israel". The New York Sun. Archived from the original on 10 June 2011. Retrieved 24 May 2010.

- ^ "Leaked Video Details the Activities of Russian Hit Squads Abroad". Jamestown. Jamestown Foundation. 27 February 2014.

- ^ "Experts Positively Identify Basayev". The Moscow News. 29 December 2006.[dead link]

- ^ Clarity in Chechen resistance, SIA Chechen Press, 31 December 2007 Archived 22 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Asprem, Egil; Granholm, Kennet (11 September 2014). Contemporary Esotericism. Routledge. ISBN 9781317543565.

- ^ "Reshenie o likvidatsii". IMDb.

External links[edit]

![]() Media related to Shamil Basaev at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Shamil Basaev at Wikimedia Commons