Maria Rundell | |

|---|---|

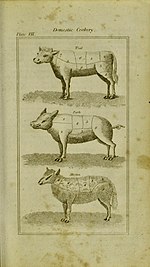

Title page of A New System of Domestic Cookery, 1806 edition | |

| Born | Maria Eliza Ketelby 1745 Ludlow, Shropshire, England |

| Died | 16 December 1828 (aged 82–83) Lausanne, Switzerland |

| Notable works | A New System of Domestic Cookery (1806) |

| Spouse |

Thomas Rundell

(m. 1766; died 1795) |

Maria Eliza Rundell (née Ketelby; 1745 – 16 December 1828) was an English writer. Little is known about most of her life, but in 1805, when she was over 60, she sent an unedited collection of recipes and household advice to John Murray, of whose family—owners of the John Murray publishing house—she was a friend. She asked for, and expected, no payment or royalties.

Murray published the work, A New System of Domestic Cookery, in November 1805. It was a huge success and several editions followed; the book sold around half a million copies in Rundell's lifetime. The book was aimed at middle-class housewives. In addition to dealing with food preparation, it offers advice on medical remedies and how to set up a home brewery and includes a section entitled "Directions to Servants". The book contains an early recipe for tomato sauce—possibly the first—and the first recipe in print for Scotch eggs. Rundell also advises readers on being economical with their food and avoiding waste.

In 1819 Rundell asked Murray to stop publishing Domestic Cookery, as she was increasingly unhappy with the way the work had declined with each subsequent edition. She wanted to issue a new edition with a new publisher. A court case ensued, and legal wrangling between the two sides continued until 1823, when Rundell accepted Murray's offer of £2,100 for the rights to the work.

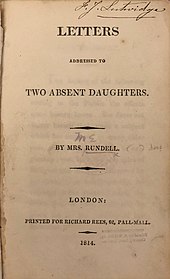

Rundell wrote a second book, Letters Addressed to Two Absent Daughters, published in 1814. The work contains the advice a mother would give to her daughters on subjects such as death, friendship, how to behave in polite company and the types of books a well-mannered young woman should read. She died in December 1828 while visiting Lausanne, Switzerland.

Biography[edit]

Rundell was born Maria Eliza Ketelby in 1745 to Margaret (née Farquharson) and Abel Johnson Ketelby; Maria was the couple's only child. Abel Ketelby, who lived with his family in Ludlow, Shropshire, was a barrister of the Middle Temple, London.[1][2] Little is known about Rundell's life; the food writers Mary Aylett and Olive Ordish observe "in one of the most copiously recorded periods of our history, when biographies of even the light ladies can be written in full, the private life of the most popular writer of the day is unrecorded".[3]

On 30 December 1766 Maria married Thomas Rundell, either a surgeon from Bath, Somerset, or a jeweller at the well-known jewellers and goldsmiths Rundell and Bridge of Ludgate Hill in the City of London.[1][a] The couple had two sons and three daughters.[1][b]

The family lived in Bath at some point,[1] and they may also have lived for a while in London.[10][11] Thomas died in Bath on 30 September 1795 after a long illness.[1] Rundell moved to Swansea, South Wales, possibly to live with a married daughter,[9][10] and sent two of her daughters to London, where they lived with their aunt and uncle.[1]

Writing[edit]

During her marriage and in widowhood, Rundell collected recipes and household advice for her daughters. In 1805, when she was 61, she sent the unedited collection to John Murray, of whose family—owners of the John Murray publishing house—she was a friend.[4] It had been sixty years since Hannah Glasse had written The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy, and forty years since Elizabeth Raffald had written The Experienced English Housekeeper—the last cookery books that had sold well in Britain—and Murray realised that there was a gap in the market.[4]

The document Rundell gave Murray was nearly ready for publication; he added a title page, the frontispiece and an index, and had the collection edited. He registered it at Stationer's Hall as his property,[12] and the first edition of A New System of Domestic Cookery was published in December 1805.[13][14][c] As was common with female authors of the time, the book was published under the pseudonym "A Lady". Rundell wanted no payment for the book, as in some social circles the receipt of royalties was thought improper,[10] and the first edition contained a note from the publishers that read:

the directions which follow were intended for the conduct of the families of the authoress's own daughters, and for the good arrangement of their table, so as to unite a good figure with proper economy ... This little work would have been a treasure to herself, when she first set out in life, and she therefore hopes it may be useful to others. In that idea it is given to the public, and as she will receive from it no emolument, so she trusts it will escape without censure.[18]

The book was well-received and became successful.[1][2] The reviewer in the European Magazine and London Review thought it an "ingenious treatise" that was "universally and perpetually interesting".[19] The unnamed male reviewer for The Monthly Repertory of English Literature wrote "we can only report that certain of our female friends (better critics on this subject than ourselves) speak favourably of the work".[20] The reviewer also admired the "sundry recipes, which may properly be called 'kitchen physic', with others, which are useful for ladies to know, and for good housewives to practise".[21] The Lady's Monthly Museum observed the work was "cheap in price, perspicuous in its directions, and satisfying in its results".[22]

Several editions of A New System of Domestic Cookery were published, enlarged and revised.[1][d] In 1808, Murray sent £150 to Rundell, saying that her gift was more profitable than he thought it would be. She replied to his letter, saying "I never had the smallest idea of any return for what really was a free gift to one whom I had long regarded as my friend".[12][e]

In 1814 Rundell published her second book, Letters Addressed to Two Absent Daughters. The work contains the advice a mother would give to her daughters.[2] The reviewer for The Monthly Review thought the book was "uniformly moral, and contains some sensible and useful reflections; particularly those on death and on friendship".[24] The reviewer for The British Critic thought the work "contains much admirable instruction; the sentiments are always good, often admirable".[25]

Rundell wrote to Murray in 1814 to complain that he was neglecting Domestic Cookery, which impinged on the book's sales.[26] She complained of one editor "He has made some dreadful blunders, such as directing rice pudding seeds to be kept in a keg of lime water, which latter was mentioned to preserve eggs in." She complained that "strange expressions" had been included in a new edition, saying "In sober English, the 2nd edition of DC has been miserably prepared for the press."[4] Murray wrote to his wife about Rundell's complaint:

I have had such a letter from Mrs Rundell, accusing me of neglecting her book, stopping the sales, etc. Her conceit passes everything; but she again desires the reviews to be sent to her, she shall have them with a little truth in a moderate dose of remonstrance from me.[26]

By 1819 the first term of Domestic Cookery's copyright had expired. That November, Rundell wrote to Murray asking him to stop selling the book, and telling him that she would be publishing a new edition of the book through Longman.[27] She obtained an injunction to ensure he was unable to continue selling the book.[28] Murray counter-sued Rundell to ensure she did not publish the book. The Lord Chancellor, John Scott, stated that neither side could have the rights, and decided that it would need to be decided by a court of law, not a court of equity.[1][29][30][f] In 1823, Rundell accepted an offer of £2,100 for her rights in the book.[32][g]

Rundell spent much of her widowhood travelling, staying for periods with family and close friends, as well as abroad.[1] Rundell's son, Edmund Waller Rundell, joined the well-known jewellers and goldsmiths Rundell and Bridge; the firm was run by Philip Rundell, a relation of Maria Rundell's late husband. Edmund later became a partner within the firm. In 1827, Philip died; he left Maria £20,000, and £10,000 each to Edmund and Edmund's wife.[33][34][h] In 1828, Rundell travelled to Switzerland. She died in Lausanne on 16 December.[1]

Works[edit]

Domestic Cookery[edit]

The first edition of A New System of Domestic Cookery comprises 290 pages, with a full index at the end.[35][36] It was written in what the historian Kate Colquhoun calls a "plain-speaking" manner;[37] the food writer Maxime de la Falaise describes it as "an intimate and charming style",[9] and Geraldene Holt considers it "strikingly practical and charmingly unpretentious".[10] The work was intended for the "respectable middle class", according to Petits Propos Culinaires.[38] Colquhoun considers that the book was "aimed at the growing band of anxious housewives who had not been taught how to run a home".[39]

Domestic Cookery provides advice on how to set up a home brewery, provides recipes for the sick, and has a section on "Directions to Servants".[40] Quayle describes the book as "the first manual of household management and domestic economy which could claim any pretension to completeness".[41] Rundell advises readers on being economical with their food, and avoiding waste.[42] Her introduction opens:

The mistress of a family should always remember that the welfare and good management of the house depend on the eye of the superior; and consequently that nothing is too trifling for her notice, whereby waste may be avoided; and this attention is of more importance now that the price of every necessary of life is increased to an enormous degree.[43]

The book contains recipes for fish, meat, pies, soups, pickles, vegetables, pastry, puddings, fruits, cakes, eggs, cheese and dairy.[44] Rundell included detailed instructions on techniques to ensure the best results.[45] Some of the recipes were from Mary Kettilby's work A Collection of Above Three Hundred Receipts in Cookery, Physick and Surgery, first published in 1714.[2]

The food writer Alan Davidson holds that Domestic Cookery does not have many innovative features, although it does have an early recipe for tomato sauce.[47][i] The fourth edition (printed in 1809) provides the first printed recipe for Scotch eggs.[47][13][j]

Subsequent editions were expanded, with some small errors corrected.[14] Additions included medical remedies and advice; the journalist Elizabeth Grice notes that these, "if efficacious, could spare women the embarrassment of submitting to a male doctor".[4] The 1840 edition was expanded by the author Emma Roberts, who included many Anglo-Indian recipes.[47][49] The new edition—the sixty-fourth—included seven recipes for curry powder, three for Mulligatawny soup[50] and seventeen curries, including: King of Oudh's, Lord Clive's, Madras, Dopiaza, Malay, plain and vegetable.[51] For this edition of Domestic Cookery, underneath Rundell's statement that she would receive no emolument from the book, Murray added a note: "The authoress, Mrs Rundell, sister of the eminent jeweller on Ludgate Hill, was afterwards induced to accept the sum of two thousand guineas from the publisher."[52]

Addressed to Two Absent Daughters[edit]

Addressed to Two Absent Daughters takes the form of thirty-eight letters from a mother to two absent daughters, Marianne and Ellen.[53] The advice included how to behave in polite company, the types of books a well-mannered young woman should read, and how to write letters.[54][55] As it was normal at the time for girls and young women to have no formal education, it was common and traditional for mothers to provide such advice.[2] The book contains no responses from the two fictional daughters,[54] although the text refers to the receipt of "your joint letters" at several points.[56]

Legacy[edit]

A New System of Domestic Cookery was the dominant cookery book of the early nineteenth century, outselling all other works.[47] There were sixty-seven editions between 1806 and 1846,[57] and it sold over half a million copies in Rundell's lifetime.[37] New editions were released into the 1880s.[4][10] In America, there were fifteen editions between 1807 and 1844,[57] and thirty-seven in total.[58]

Rundell's work was plagiarised by at least five other publishers.[59] In 1857, when Isabella Beeton began writing the cookery column for The Englishwoman's Domestic Magazine, many of the recipes were copied from Domestic Cookery.[60] In 1861, Isabella's husband, Samuel, published Mrs Beeton's Book of Household Management, which also contained several of Rundell's recipes.[61][k] Domestic Cookery was also heavily plagiarised in America,[58] with Rundell's recipes being reproduced in Mary Randolph's 1824 work The Virginia House-Wife and Elizabeth Ellicott Lea's A Quaker Woman's Cookbook.[66]

Rundell is quoted around twenty times in the Oxford English Dictionary,[67] including for the terms "apple marmalade",[68] "Eve's pudding",[69] "marble veal"[70] and "neat's tongue".[71]

Grice, writing in The Daily Telegraph, and the journalist Severin Carrell, writing in The Guardian, both consider Rundell a "domestic goddess",[4][5][l] although Grice writes that "she didn't have "Nigella [Lawson]'s sexual frisson, or Delia [Smith]'s uncomplicated kitchen manners".[4] For Grice, "Compared with the illustrious Eliza Acton—who could write better—and the ubiquitous Mrs Beeton—who died young—Mrs Rundell has unfairly slipped from view."[4]

Rundell has been admired by several modern cooks and food writers. The 20th-century cookery writer Elizabeth David references Rundell in her articles, collected in Is There a Nutmeg in the House,[72] which includes her recipe for "burnt cream" (crème brûlée).[59] In her 1970 work Spices, Salt and Aromatics in the English Kitchen, David includes Rundell's recipe for fresh tomato sauce; she writes that this "appears to be one of the earliest published English recipes for tomato sauce".[73] In English Bread and Yeast Cookery (1977), she includes Rundell's recipes for muffins, Lancashire pikelets (crumpets), "potato rolls", Sally Lunns, and black bun.[74] The food writer and chef Michael Smith used some of Rundell's recipes in his 1973 book Fine English Cookery, which re-worked historical recipes for modern times.[75][m] The food writer Jane Grigson admired Rundell's work, and in her 1978 book Jane Grigson's Vegetable Book, referred to Rundell's writing, and included her recipe for red cabbage stewed in the English manner.[76]

Notes and references[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Sources disagree on Thomas's career. Among those who consider Thomas a surgeon are the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography,[1] The Daily Telegraph,[4] The Guardian,[5] the historian Sheila Hardy[6] and the television cook Clarissa Dickson Wright;[7] among those who believe he was a jeweller are The Feminist Companion to Literature in English,[2] Aylett and Ordish[8] and, separately, the cookery writers Maxime McKendry[9] and Geraldene Holt.[10]

- ^ Aylett and Ordish state it was "an unspecified number of daughters";[8] Severin Carrell, writing in The Guardian, says seven daughters.[5]

- ^ The publication date is given in most sources as 1806,[1][13][15] which is the date shown on the title page.[16] A court case of 1821 stated the book was published in November 1805;[12] the book historian Eric Quayle observes that the edition dated 1806 on the title page has on the opposite page "Published as the Act directs, Nov 1st, 1805, by J. Murray."[14][16] A copy held at the University of Leeds is dated 1806 and showed the 1805 printing date; a handwritten inscription on the title page is dated 3 December 1805.[17] Some sources state 1808 for the first edition.[2][3]

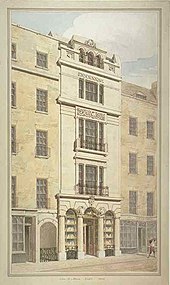

- ^ So financially successful was A New System of Domestic Cookery that Murray used its copyright as surety when he purchased the lease of 50 Albemarle Street for his new house.[1]

- ^ £150 in 1808 equates to approximately £12,000 in 2024, according to calculations based on the Consumer Price Index measure of inflation.[23]

- ^ A court of equity deals with matters arising in disputes over business or property, including intellectual property.[31]

- ^ £2,100 in 1823 equates to approximately £202,000 in 2024, according to calculations based on the Consumer Price Index measure of inflation.[23]

- ^ £20,000 in 1827 equates to approximately £1,842,000 in 2024, according to calculations based on the Consumer Price Index measure of inflation.[23]

- ^ Rundell's recipe called for ripe tomatoes baked in an earthenware jar. She directed that, when soft, they should be skinned, and the pulp mixed with capsicum vinegar, garlic, ginger and salt. The resulting mixture was to be bottled and stored in a dry place.[46] Colquhoun states that the tomato sauce recipe was the first printed recipe for the condiment.[48]

- ^ The recipe was for five pullet eggs; the dish was to be served hot with gravy.[46]

- ^ Rundell's work was not the only one to be copied by the Beetons. Other cookery books plagiarised include Elizabeth Raffald's The Experienced English Housekeeper, Marie-Antoine Carême's Le Pâtissier royal parisien,[62] Louis Eustache Ude's The French Cook, Alexis Soyer's The Modern Housewife or, Ménagère and The Pantropheon, Hannah Glasse's The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy, Eliza Acton's Modern Cookery for Private Families and the works of Charles Elmé Francatelli.[63][64][65]

- ^ Grice calls Rundell "a Victorian domestic goddess";[4] Carrell considers her "the original domestic goddess".[5]

- ^ Other cooks whose work was reimagined included Hannah Glasse, Elizabeth Raffald and Eliza Acton.[75]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Lee & McConnell 2004.

- ^ a b c d e f g Blain, Clements & Grundy 1990, p. 933.

- ^ a b Aylett & Ordish 1965, p. 139.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Grice 2007.

- ^ a b c d Carrell 2007.

- ^ Hardy 2011, p. 95.

- ^ Dickson Wright 2011, 3840.

- ^ a b Aylett & Ordish 1965, p. 140.

- ^ a b c McKendry 1973, p. 107.

- ^ a b c d e f Holt 1999, p. 547.

- ^ Aylett & Ordish 1965, p. 141.

- ^ a b c Jacob 1828, p. 311.

- ^ a b c "Maria Rundell – John Murray Archive". National Library of Scotland.

- ^ a b c Quayle 1978, p. 119.

- ^ Batchelor 1985, p. 8.

- ^ a b Rundell 1806, title page.

- ^ Rundell 1806, frontispiece, title page.

- ^ Rundell 1806, Advertisement.

- ^ "Reviews". The London Review, p. 28.

- ^ "Article IX. A New System of Domestic Cookery". The Monthly Repertory of English Literature, p. 177.

- ^ "Article IX. A New System of Domestic Cookery". The Monthly Repertory of English Literature, p. 178.

- ^ "A New System of Domestic Cookery". The Lady's Monthly Museum, p. 178.

- ^ a b c Clark 2018.

- ^ "Monthly Catalogue, Miscellaneous". The Monthly Review, pp. 325–326.

- ^ "Miscellanies". The British Critic 1814, p. 661.

- ^ a b Aylett & Ordish 1965, p. 153.

- ^ Dyer 2013, p. 121.

- ^ Jacob 1828, p. 312.

- ^ Smiles 2014, pp. 123–124.

- ^ Jacob 1828, p. 316.

- ^ "Chancery Division". Encyclopaedia Britannica.

- ^ Dyer 2013, p. 122.

- ^ "Fashion and Table-Talk". The Globe.

- ^ "Mr Rundell's Will". Lancaster Gazette.

- ^ "A New System of Domestic Cookery". WorldCat.

- ^ Rundell 1806, p. 277.

- ^ a b Colquhoun 2007, p. 262.

- ^ Batchelor 1985, p. 9.

- ^ Colquhoun 2007, p. 261.

- ^ Rundell 1806, pp. 236, 217, 269.

- ^ Quayle 1978, p. 125.

- ^ Rumohr 1993, p. 10.

- ^ Rundell 1806, p. i.

- ^ Rundell 1806, pp. 1, 20, 89, 95, 118, 128, 133, 143, 156, 212, 230.

- ^ Colquhoun 2007, pp. 262–263.

- ^ a b c Rundell 1809, p. 207.

- ^ a b c d Davidson 1999, p. 279.

- ^ Colquhoun 2007, p. 266.

- ^ Beetham 2008, p. 401.

- ^ Rundell 1840, pp. 299–301, 26–27.

- ^ Rundell 1840, pp. 289, 290, 290–291, 293, 295, 292; recipes cited respectively.

- ^ Rundell 1840, p. iii.

- ^ Rundell 1814, pp. 1, 7, 24, 297.

- ^ a b "Monthly Catalogue, Miscellaneous". The Monthly Review, p. 326.

- ^ "Miscellanies". The British Critic 1814, pp. 661, 662.

- ^ Rundell 1814, pp. 4, 9, 33, 77.

- ^ a b Willan & Cherniavsky 2012, p. 213.

- ^ a b Randolph 1984, p. xx.

- ^ a b David 2001, p. 250.

- ^ Aylett & Ordish 1965, p. 210.

- ^ Hughes 2006, p. 210.

- ^ Broomfield 2008, p. 104.

- ^ Hughes 2006, pp. 198–201, 206–210.

- ^ Hughes 2014.

- ^ Brown 2006.

- ^ Weaver 2016, p. xxxviii.

- ^ "Maria Rundell; quotations". Oxford English Dictionary.

- ^ "apple marmalade". Oxford English Dictionary.

- ^ "Eve's pudding". Oxford English Dictionary.

- ^ "marble veal". Oxford English Dictionary.

- ^ "neat's tongue". Oxford English Dictionary.

- ^ David 2001, pp. 250, 265.

- ^ David 1975, pp. 84–85.

- ^ David 1979, pp. 345–346, 359, 326, 469, 449–451; recipes cited respectively.

- ^ a b Colquhoun 2007, p. 363.

- ^ Grigson 1979, p. 435.

Sources[edit]

Books[edit]

- Aylett, Mary; Ordish, Olive (1965). First Catch Your Hare. London: Macdonald. OCLC 54053.

- Blain, Virginia; Clements, Patricia; Grundy, Isobel (1990). The Feminist Companion to Literature in English: Women Writers from the Middle Ages to the Present. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-04854-4.

- Colquhoun, Kate (2007). Taste: the Story of Britain Through its Cooking. New York: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-5969-1410-0.

- David, Elizabeth (1975) [1970]. Spices, Salt and Aromatics in the English Kitchen. Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-1404-6796-3.

- David, Elizabeth (2001) [2000]. Is There a Nutmeg in the House?. Jill Norman (ed). London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-029290-9.

- David, Elizabeth (1979) [1977]. English Bread and Yeast Cookery. Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-1402-9974-8.

- Davidson, Alan (1999). The Oxford Companion to Food. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-1921-1579-9.

- Dickson Wright, Clarissa (2011). A History of English Food (Kindle ed.). London: Random House. ISBN 978-1-4481-0745-2.

- Grigson, Jane (1979). Jane Grigson's Vegetable Book. New York: Atheneum. ISBN 978-0-689-10994-2.

- Hardy, Sheila (2011). The Real Mrs Beeton: The Story of Eliza Acton. Stroud, Gloucestershire: The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-6122-9.

- Holt, Geraldene (1999). "Rundell, Maria". In Sage, Lorna (ed.). The Cambridge Guide to Women's Writing in English. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 547. ISBN 978-0-5214-9525-7.

- Hughes, Kathryn (2006). The Short Life and Long Times of Mrs Beeton. London: HarperCollins Publishers. ISBN 978-1-8411-5374-2.

- Jacob, Edward (1828). Reports of Cases Argued and Determined in the High Court of Chancery, During the Time of Lord Chancellor Eldon. London: J. Butterworth and Son. OCLC 4730594.

- McKendry, Maxime (1973). Boxer, Arabella (ed.). The Seven Centuries Cookbook: From Richard II to Elizabeth II. New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-045153-7.

- Quayle, Eric (1978). Old Cook Books: an illustrated history. London: Studio Vista. ISBN 978-0-2897-0707-4.

- Randolph, Mary (1984). Hess, Karen (ed.). The Virginia House-wife. Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-87249-423-7.

- Rumohr, Carl Friedrich von (1993) [1822]. The Essence of Cookery. Translated by Yeomans, Barbara. London: Prospect Books. ISBN 978-0-9073-2549-9.

- Rundell, Maria (1806). A New System of Domestic Cookery (1st ed.). London: J. Murray. OCLC 34572746.

- Rundell, Maria (1809). A New System of Domestic Cookery (4th ed.). London: J. Murray. OCLC 970734084.

- Rundell, Maria (1840). A New System of Domestic Cookery (64th ed.). London: J. Murray. OCLC 970782578.

- Rundell, Maria (1814). Letters Addressed to Two Absent Daughters. London: Richard Rees. OCLC 1333333.

- Smiles, Samuel (2014). A Publisher and his Friends. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-07392-9.

- Weaver, William Woys (2016). "Introduction". In Lea, Elizabeth Ellicott; Holton, Sandra (eds.). A Quaker Woman's Cookbook. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-1-5128-1925-0.

- Willan, Anne; Cherniavsky, Mark (2012). The Cookbook Library: Four Centuries of the Cooks, Writers, and Recipes That Made the Modern Cookbook. Oakland, CA: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-24400-9.

Journals[edit]

- "Article IX. A New System of Domestic Cookery". The Monthly Repertory of English Literature. 3: 176–179. 1808.

- Batchelor, Ray (March 1985). "Eating with Mrs Rundell". Petits Propos Culinaires. 16: 8–12.

- Beetham, Margaret (2008). "Good Taste and Sweet Ordering: Dining with Mrs Beeton". Victorian Literature and Culture. 36 (2): 391–406. doi:10.1017/S106015030808025X. JSTOR 40347196. S2CID 161615601.

- Broomfield, Andrea (Summer 2008). "Rushing Dinner to the Table: The Englishwoman's Domestic Magazine and Industrialization's Effects on Middle-Class Food and Cooking, 1852–1860". Victorian Periodicals Review. 41 (2): 101–123. doi:10.1353/vpr.0.0032. JSTOR 20084239. S2CID 161900658.

- Dyer, Gary (Summer 2013). "Publishers and Lawyers". The Wordsworth Circle. 44 (2/3): 121–126. doi:10.1086/TWC24044234. S2CID 160060572.

- Lee, Elizabeth; McConnell, Anita (2004). "Rundell [née Ketelby], Maria Eliza (1745–1828)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/24278. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- "Miscellanies". The British Critic. 2: 660–62. December 1814.

- "Monthly Catalogue, Miscellaneous". The Monthly Review. 74: 325–326. July 1814.

- "A New System of Domestic Cookery". The Lady's Monthly Museum: 177–178. April 1807.

- "Reviews". The London Review. 1: 28. 1 February 1809.

Newspapers[edit]

- Brown, Mark (2 June 2006). "Mrs Beeton couldn't cook but she could copy, reveals historian". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015.

- Carrell, Severin (26 June 2007). "Archive Reveals Britain's First Domestic Goddess". The Guardian.

- "Fashion and Table-Talk". The Globe. 26 February 1827. p. 3.

- Grice, Elizabeth (27 June 2007). "How Mrs Rundell Whipped up a Storm". The Daily Telegraph.

- "Mr Rundell's Will". Lancaster Gazette. 3 March 1827. p. 1.

Internet[edit]

- "apple marmalade". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. Retrieved 5 June 2019. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- "Chancery Division". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved 7 August 2019.

- Clark, Gregory (2018). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 30 January 2018.

- "Eve's pudding". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. Retrieved 5 June 2019. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- Hughes, Kathryn (15 May 2014). "Mrs Beeton and the Art of Household Management". British Library. Archived from the original on 6 January 2016. Retrieved 27 November 2015.

- "marble veal". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. Retrieved 5 June 2019. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- "Maria Rundell; quotations". Oxford English Dictionary. Retrieved 16 July 2019.

- "Maria Rundell – John Murray Archive". National Library of Scotland. Retrieved 13 July 2019.

- "neat's tongue". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. Retrieved 5 June 2019. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- "A New System of Domestic Cookery". WorldCat. Retrieved 13 July 2019.