Louis Couperus | |

|---|---|

Louis Couperus in 1917 | |

| Born | Louis Marie-Anne Couperus 10 June 1863 The Hague, Netherlands |

| Died | 16 July 1923 (aged 60) De Steeg, Netherlands |

| Occupation | Novelist |

| Years active | 1878–1923 |

Louis Marie-Anne Couperus (10 June 1863 – 16 July 1923) was a Dutch novelist and poet. His oeuvre contains a wide variety of genres: lyric poetry, psychological and historical novels, novellas, short stories, fairy tales, feuilletons and sketches. Couperus is considered to be one of the foremost figures in Dutch literature. In 1923, he was awarded the Tollensprijs (Tollens Prize).

Couperus and his wife travelled extensively in Europe and Asia, and he later wrote several related travelogues which were published weekly.

Youth[edit]

Louis Marie-Anne Couperus was born on 10 June 1863 at Mauritskade 11 in The Hague, Netherlands, into a long-established, Indo family of the colonial landed gentry of the Dutch East Indies.[1] He was the eleventh and youngest child of John Ricus Couperus (1816–1902), a prominent colonial administrator, lawyer and landheer or lord of the private domain (particuliere land) of Tjikopo in Java,[2] and Catharina Geertruida Reynst (1829–1893). Through his father, he was a great-grandson of Abraham Couperus (1752-1813), Governor of Malacca, and Willem Jacob Cranssen (1762-1821), Governor of Ambon with a female-line, Eurasian lineage that goes back even earlier to the mid-eighteenth century.[1]

Four of the ten siblings had died before Louis was born. Couperus was baptized on 19 July 1863 in the Eglise wallonne in The Hague.[3]: p.31–59 When Louis reached the age of five, his youngest sister, Trudy, was twelve years old and his youngest brother, Frans, eleven.[3]: p.55 In The Hague he followed lessons at the boarding school of Mr. Wyers, where he first met his later friend Henri van Booven.[3]: p.61 On 6 November 1872 the Couperus family left home, travelled by train to Den Helder and embarked on the steamboat Prins Hendrik, which would bring them back to the Dutch East Indies.[3]: p.65 They arrived on 31 December 1872 in Batavia, where they spent the night at the then famous Hotel des Indes.[3]: p.68 The family settled in a house in Batavia, located on the Koningsplein and the mother of Couperus and his brother Frans (who was suffering from peritonitis) returned to the Netherlands in December 1873; his mother returned to the Dutch East Indies in April 1874.[3]: p.68–69 So Couperus spent part of his youth (1873–1878) in the Dutch East Indies,[4] going to school in Batavia.

Here he met his cousin, Elisabeth Couperus-Baud, for the first time. In his novel De zwaluwen neergestreken (The swallows flew down), he wrote about his youth:

- "We are cousins and have played together. We danced together at children's balls. We still have our baby pictures. She was dressed in a marquise dress and I was dressed as a page. My garment was made of black velvet and I was very proud of my first travesti."[5]

In the Dutch East Indies, Couperus also met his future brother-in-law for the first time, Gerard de la Valette (a writer and official at the Dutch Indian Government who would marry his sister Trudy), who wrote in 1913 about his relationship with Couperus:

- We met first at Batavia, when he was a boy of ten years and I was a young man. We saw each other at rather large intervals. Yet I saw him often enough, as a boy and a young man, that we developed a good and familiar relationship.[3]: p.71

After he finished primary school, Couperus attended the Gymnasium Willem III in Batavia.[3]: p.78 In the summer of 1878 Couperus and his family returned to the Netherlands, where they went to live in a house at the Nassaukade (plein) 4.[3]: p.83 In The Hague Couperus was sent to the H.B.S. school; during this period of his life, he spent a lot of time at the Vlielander-Hein family (his sister was married to Benjamin Marius Vlielander Hein); later their son, François Emile Vlielander Hein (1882–1919), was his favourite nephew, who helped him with his literary work.[3]: p.84 At the HBS Couperus met his later friend Frans Netscher; during this period of his life, he read the novels written by Émile Zola and Ouida (the latter he would meet in Florence, years later).[3]: p.86–87 When Couperus' school results did not improve, his father send him to a school where he was trained to be a teacher in the Dutch language. In 1883 he attended the opera written by Charles Gounod Le tribut de Zamora; he later used elements of this opera in his novel Eline Vere.[3]: p.94

Start of Couperus' career as a writer[edit]

In 1885 plans were made to compose an operetta for children. Virginie la Chapelle wrote the music, and Couperus provided the lyrics for De schoone slaapster in het bosch ("Sleeping beauty in the forest"). The opera was staged by a hundred children at the Koninklijke Schouwburg (Royal Theatre) in The Hague.[3]: p.94 In January 1885 Couperus had already written one of his early poems, called Kleopatra.[3]: p.95 Other writings from this period include the sonnet Een portret ("A Portrait") and Uw glimlach of uw bloemen ("Your smile or your flowers").[3]: p.96 In 1882, Couperus started reading Petrarch and had the intention to write a novel about him, which was never realized, although he did publish the novella In het huis bij den dom ("In the house near the church"), loosely inspired by Plutarch.[3]: p.98 When Couperus just had finished his novella Een middag bij Vespaziano ("An Afternoon at Vespaziano"), he visited Johannes Bosboom and his wife Anna Louisa Geertruida Bosboom-Toussaint, whose works Couperus greatly admired. Couperus let Mrs. Bosboom-Toussaint read his novella, which she found very good.[3]: p.99 In 1883 Couperus started writing Laura; this novella was published in parts in De Gids (a Dutch literary magazine) in 1883 and 1884. In 1885 Couperus' debut in book form, Een lent van vaerzen ("A ribbon of poems") was published (by publisher J.L. Beijers with a book cover designed by painter Ludwig Willem Reymert Wenckebach).[3]: p.100 In these days a person Couperus greatly admired for his sense of beauty and intelligence was writer Carel Vosmaer, whom he frequently met while walking in the center of The Hague.[3]: p.101

In 1883 Couperus saw Sarah Bernhardt performing in The Hague, but was more impressed by her dresses than her performance itself.[3]: p.106 The next year, John Ricus Couperus, father of Louis Couperus, sold his family estate "Tjicoppo", located in the Dutch East Indies and gave order to build a house at the Surinamestraat 20, The Hague. Here Couperus continued writing poetry and his study of Dutch literature.[3]: p.108 In June 1885 he was appointed member of the very prestigious Maatschappij der Nederlandse Letterkunde (Society of Dutch Literature), two years after he published Orchideeën. Een bundel poëzie en proza ("Orchids. A Bundle of Poetry and Prose"), which had received mixed reviews. Journalist Willem Gerard van Nouhuys wrote that Orchideeën lacked quality, Jacob Nicolaas van Hall was positive, and Willem Kloos called it "literary crap".[3]: p.110 Couperus passed his exam on 6 December 1886 and received his certificate, which allowed him to teach at secondary schools. However, he did not aspire to a teaching career and decided to continue writing literature instead.[3]: p.114 At the end of 1887 he started to write what was to become his most-famous novel, Eline Vere.[3]: p.114

Eline Vere, the beginning of success[edit]

Shortly before Couperus wrote Eline Vere, he had read War and Peace and Anna Karenina, written by Leo Tolstoy. The structure of Couperus' book Eline Vere was similar to that of Anna Karenina (division into short chapters).[3]: p.114 He had also just read Ghosts, a play written by Henrik Ibsen; reference to the leading character of Ghosts is made when Eline Vere is delirious with fever and cries: "Oh god, the ghosts, approaching grinning" – also the suicide by the main characters in Eline Vere and in Ghosts by taking an overdose of morphine is the same.[3]: p.122 Between 17 June until 4 December 1888, the novel Eline Vere was published in the Dutch newspaper Het Vaderland; a reviewer in the Algemeen Handelsblad wrote: "The writer has talent".[6] Meanwhile, Couperus wrote a novella called Een ster ("A Star"), which was published in "Nederland" and made a journey to Sweden.[3]: p.124 In this period of his life, Couperus was an active member of the drama club of writer Marcel Emants ("Utile et Laetum" meaning 'useful and happy'), and here he met a new friend, Johan Hendrik Ram, a captain of the grenadiers, who would later commit suicide (December 1913).[3]: p.126 In April 1890 the Nieuwe Gids (New Guide) published a review of Eline Vere, written by Lodewijk van Deyssel, in which he wrote "the novel of Mr. Couperus is a good and a literary work". Couperus also met a new friend, writer Maurits Wagenvoort, who invited Couperus and painter George Hendrik Breitner to his home.[3]: p.126–127

A second edition of Eline Vere was published within a year. Couperus finished his next novel, Noodlot ("Fate") in May 1890; this novel was then published in De Gids. It is possible that the leading character of Noodlot, Frank, was inspired by the character of Couperus' friend, Johan Hendrik Ram, a strong and healthy military person.[3]: p.132 Couperus now started reading Paul Bourget's novel Un coeur de femme, which inspired him during the writing of his novella Extaze ("Ecstasy").[3]: p.135 In July 1890 he completed Eene illuzie ("An Illusion") and on 12 August 1890 received the prestigious D.A. Thiemeprijs (D.A. Thieme prize, named after the noted publisher).[3]: p.137 [7] In October that same year, he travelled to Paris, where he received a letter from his publisher-to-be, L.J. Veen, asking permission to publish Noodlot, which offer Couperus rejected because this book was supposed to be published by Elsevier.[3]: p.141 When his uncle Guillaume Louis Baud died, Couperus went back to The Hague to attend the funeral. Here Couperus decided to marry his cousin Elisabeth Couperus-Baud. The marriage took place on 9 September 1891 in The Hague.

More successes as a writer[edit]

On 21 September 1891, Couperus and his wife settled in a small villa at the Roeltjesweg (now Couperusweg) in Hilversum;[8] after Couperus finished his new book Extaze in October 1891 he wrote Uitzichten ("Views") and started with his new romantic and spiritual novella Epiloog ("Epilogue").[3]: p.152 Extaze was published in 1892 in The Gids, and Couperus asked publisher L.J. Veen to publish it as a novel, but refused the offer Veen made him.[3]: p.153 In 1891 an English translation of Noodlot, Footsteps of Fate (translation made by Clara Bell) and in 1892 an English translation of Eline Vere were released. Meanwhile, L.J. Veen made Couperus a better offer, which he accepted, and Couperus received from Oscar Wilde his novel The Picture of Dorian Gray; Wilde had read the translation of Couperus' Footsteps of Fate.[9] and wrote to Couperus to compliment him with his book.[3]: p.155 Elisabeth Couperus-Baud translated Wilde's novel into Dutch: Het portret van Dorian Gray. Dutch critics wrote divergent reviews about Extaze: writer and journalist Henri Borel said that, the book was something like a young boy messing with an egg, while Lodewijk van Deyssel found it great. Frederik van Eeden wrote that he had a specific aversion against the book.[3]: p.157 Couperus and his wife moved to The Hague, where Couperus wrote Majesteit ("Majesty"), after he had read an article in The Illustrated London News about Nicholas II of Russia.[3]: p.159 Gerrit Jäger, a play writer, wrote a theatre performance of Noodlot; it was performed in 1892 by the Rotterdam theatre company, and the then-famous Dutch actor Willem Royaards, who was an acquaintance of Couperus, played one of the leading characters.[3]: p.160 On 1 February 1893 Couperus and his wife left for Florence, but they had to return because of the death of Couperus' mother. He wrote about how she rested on her deathbed in his novel Metamorfoze ("Metamorphosis").[3]: p.161 During this time Elisabeth Couperus-Baud was translating George Moore's novel Vain Fortune, while Majesteit was published in The Gids.[3]: p.164

In 1894 Couperus joined the editorial board of De Gids; other members were Geertrudus Cornelis Willem Byvanck (a writer), Jacob Nicolaas van Hall (writer and politician), Anton Gerard van Hamel (professor in the French language), Ambrosius Hubrecht and Pieter Cort van der Linden. In September 1893 Couperus and his wife left for Italy for the second time. In Florence they stayed in a pension close to the Santa Maria Novella; here Couperus wrote in November 1893 a sketch, Annonciatie, a literary description of the painting of the same name by Simone Martini and Lippo Memmi in the Uffizi gallery.[3]: p.165 In December Couperus and his wife visited Rome, where Couperus wrote San Pietro (his impression of St. Peter's Basilica), Pincio, Michelangelo's cupola, Via Appia and Brief uit Rome ("Letter from Rome"). In these works, Couperus gave references to the works he had read about Rome: Ariadne by Ouida, Rienzi by Bulwer, Transformation by Hawthorne, Voyage en Italie by Taine and Cosmopolotis by Bourget.[3]: p.166 In February 1894 Couperus travelled to Naples and Athens, and then returned to Florence, where he visited Ouida. Couperus and his wife returned to the Netherlands, where Elisabeth Couperus-Baud made a translation of George Moore's Vain Fortune; they went to live in the house at the Jacob van der Doesstraat 123. During this time Gerrit Jäger committed suicide by drowning. Couperus now started working on what was to become Wereldvrede ("World Peace") and wrote a translation of Flaubert's La Tentation de Saint Antoine.[3]: p.170–172

Consolidation phase[edit]

In 1894 an English translation was made by Alexander Teixeira de Mattos of Majesteit; reviewers were not satisfied, and in the Netherlands Couperus new novel Wereldvrede was seen by critics as a flat novel, intended for women. Apart from that Lodewijk van Deyssel wrote a review in which he asked Couperus to get lost ("De heer Couperus kan van mij ophoepelen"), and Couperus himself ended his editorship at De Gids (April 1895).[3]: p.175–177 In October 1895 Couperus and his wife travelled to Italy again, where they visited Venice; they stayed at a hotel near the Piazza San Marco, and Couperus studied the works of Tintoretto, Titian and Veronese. The next city they visited was Rome, where Couperus would receive a number of bad reviews of his book Wereldvrede.[3]: p.179 In Rome he met Dutch sculptor Pier Pander and Dutch painter Pieter de Josselin de Jong. In March 1896 Couperus and his wife returned to the Netherlands.[3]: p.184–185 In 1896 Hoge troeven ("High Trumps") was published with a book cover designed by Hendrik Petrus Berlage, and in April 1896 Couperus started writing Metamorfoze ("Metamorphosis"). In September Couperus visited Johan Hendrik Ram in Zeist, where Ram stayed with his father. Couperus spoke with Ram about Metamorfoze. That same year Couperus spend some time in Paris.[3]: p.191 In 1897 Couperus finished writing Metamorfoze, which was to be published in De Gids. Meanwhile, Elisabeth Couperus-Baud translated Olive Schreiner's Trooper Peter Halket of Mashonaland.[3]: p.196 That same year Couperus and his wife left for Dresden but also spend some time in Heidelberg. In August 1897 Couperus started with his new book Psyche and was appointed officer in the Order of Orange-Nassau.[3]: p.199 In January 1898, De Gids started publishing chapters of Psyche.

In February 1898 Couperus travelled to Berlin, where he visited Else Otten, the German translator of his books and who would also translate Psyche into German.[3]: p.206 With Elisabeth Couperus-Baud he left the Netherlands in May 1898 for a short trip to London, where they met friends and visited Ascot Racecourse; Alexander Teixeira de Mattos introduced Couperus and his wife during a high tea to English journalists and literary people. Couperus also met Edmund Gosse, who had written a foreword to Footsteps of Fate in 1891, and English painter Lawrence Alma-Tadema, who was a brother-in-law of Gosse.[3]: p.210–211 Via Oxford, Couperus and his wife returned to the Netherlands, where he finished Fidessa in December 1898. Couperus and his wife then left for the Netherlands Dutch Indies and arrived at the end of March 1899 in Tanjung Priok. In June they visited Couperus sister Trudy and her husband Gerard Valette, who was working as a resident at Tegal. Here Couperus started to write his new novel, Langs lijnen der geleidelijkheid (Inevitable). When Gerard Valette and his wife had to move to Pasuruan because of Valette's work, Couperus and his wife spend some time in Gabroe (Blitar), where Couperus observed a spirit; this experience he would later use in his novel The Hidden Force (1900).[3]: p.224

After the Hidden Force[edit]

Many of the details about the life and works of a resident in the Dutch East Indies Couperus derived from his brother-in-law De la Valette. He characterized The Hidden Force as: The Hidden Force gives back especially the enmity of the mysterious Javanese soul and atmosphere, fighting against the Dutch conqueror.[3]: p.226 Meanwhile, Couperus received a letter from his friend Johan Hendrik Ram, in which Ram wrote that he and lieutenant Lodewijk Thomson were about to travel to South Africa to follow the course of the Boer Wars as military diplomats. In March 1900 Couperus and his wife travelled back to the Netherlands, where in De Gids the text of Inevitable was published.[3]: p.228 In October 1900 Couperus and his wife moved to Nice, where Couperus read Henryk Sienkiewicz' With Fire and Sword, The Deluge and Quo Vadis, while his own The Hidden Force was published in the Netherlands.[3]: p.251 Meanwhile, Couperus started to work on his new novels Babel and De boeken der kleine zielen ("The Book of Small Souls"). In 1902 he was asked to become a member of the editorial board of a new magazine called "Groot Nederland", together with W.G. van Nouhuys and Cyriel Buysse.[3]: p.276 In October 1902 Couperus' father died at the age of 86. His house at Surinamestraat 20, The Hague was eventually sold to Conrad Theodor van Deventer. Couperus and his wife kept living in Nice, but Couperus went in January 1903 to Rome, where he met Pier Pander again and also received a letter from his publisher L.J. Veen, in which he complained that Couperus' books did not sell.[3]: p.292 In May 1903 Couperus published Dionyzos-studiën ("Studies of Dionysus") in Groot Nederland, in which Couperus paid tribute to classical antiquity (a doctrine without original sin) and especially to the god Dionysus.[3]: p.296

Couperus left that year (1903) again for Italy (Venice) and went to Nice in September. During the winter of 1903–1904, he read Jean Lombard's work about Roman emperor Elagabalus; in 1903 Georges Duviquet published his Héliogabale, which was just what Couperus needed for his idea to write a novel about a crazy emperor (De berg van licht, "The Mountain of Light"). Meanwhile, to pay his bills, he wrote Van oude menschen, de dingen, die voorbij gaan ("Of old people, the things that pass").[3]: p.302 In 1905 he published De berg van licht, which was rather controversial as it dealt with the subject of homosexuality. In 1906 Couperus and his wife left for Bagni di Lucca (Italy), where they stayed at Hotel Continental and were introduced to Eleonora Duse. In May 1907 Aan den weg der vreugde, a novella Couperus wrote while staying at Bagni di Lucca, was published in Groot Nederland; he received another letter from L.J. Veen, saying that Couperus' books did not sell well, and so Couperus wrote a farewell letter to Veen in which he told Veen this was the end of their business relationship.[3]: p.341 During the summer of 1907 Couperus wrote in Siena the story Uit de jeugd van San Francesco van Assisi'("From the youth of St. Francis of Assisi") to be published in Groot Nederland. From this period on Couperus claimed that the days of novels were counted and that short stories (called short novels by Couperus) were the novels of the future. Couperus would write a series of short stories, which he published the then coming years in magazines such as "De Locomotief", "De Telegraaf" and the "Kroniek".[3]: p.347

Endless travelling[edit]

During the winter of 1908 Couperus resided in Florence, where he translated John Argyropoulos' Aristodemus; he published his translation in Groot Nederland. In August 1908 Couperus and his wife started a pension lodge in Nice and placed an advert in the New York Herald to attract future guests. As of 27 November 1909 Couperus started publishing weekly serials in the Dutch newspaper Het Vaderland; he also published Korte arabesken ("Short Arabesques", 1911, with publisher Maatschappij voor goede en goedkoope lectuur) and a cheap edition of De zwaluwen neêr gestreken... ("The Swallows Flew Down", with publisher Van Holkema & Warendof). In December 1910 Couperus wrote in his sketch Melancholieën ("Melancholia") about the death of his father, mother, sister and brother:

- "They are the ghosts of Death ... These are the shades of my grey father, my adored mother, they are the ghosts of my sister, brother and friend. And between their shadows are the pale ghosts of the Commemorations ... Because the room is full of ghosts and ghosts. My silent, staring eyes are full of tears and I feel old and tired and afraid."[3]: p.369

In the second part of 1910, Couperus started to write a novel again, despite the fact he earlier had said he never would write one again. This novel was to be called Antiek toerisme, een roman uit Oud-Egypte ("Tourism in Antiquity, a Novel from Ancient Egypt") and was published in Groot Nederland. The book would be rewarded with the "Nieuwe Gids prize for prose" in 1914. At the end of 1910, Couperus and his wife gave up their pension in Nice and travelled to Rome. In Rome Couperus collected and rearranged some of his serials, which he intended to publish in a book, Schimmen van schoonheid ("Shadows of Beauty").[3]: p.379

Since Couperus and publisher L.J. Veen were unable to agree on the payment of Couperus, Couperus then published Schimmen van schoonheid and Antiek Toerisme with publisher Van Holkema en Warendorf. In Rome Couperus visited Museo Barracco di Scultura Antica, San Saba, the Villa Madama and the Colosseum (among other things). He also paid a visit to the Borgia Apartment and wrote a number of sketches about Lucrezia and Pinturicchio, who had painted her.[3]: p.385 In 1911 he wrote in Groot Nederland a sketch about Siena and Ostia Antica. He read Gaston Boissier's Promenades archéologiques and made long walks through the ancient ruins of Rome. He also visited the exhibition in the Belle Arti in Florence, where also Dutch painters exhibited their work. Here he met Willem Steelink and Arnold Marc Gorter, who gave him a warm welcome.[3]: p.388 Couperus wrote about the travelling he and his wife constantly did: your living or not living, what hast thou found, O thou poor seekers, O thou poor vagabonds, rich in suitcases? [3]: p.393 Couperus spend the winter of 1911–1912 in Florence; meanwhile the Greco-Turkish War broke out and influenced life in Florence as well. Couperus wrote a sketch called De jonge held ("The Young Hero") about the son of friends in Italy who returned wounded from the front.[3]: p.405 In December Couperus and his wife left for Sicily but spent some time in Orvieto, where they stayed in the same hotel that Bertel Thorvaldsen had once visited. Hereafter they travelled to Naples, where Couperus admired the Farnese Hercules, which inspired him to start writing his next novel, Herakles.[3]: p.411

Trading places[edit]

The first chapters of Herakles appeared during the first half of 1912 in Groot Nederland. Couperus then stayed in Sicily, where he visited Syracuse and Messina; he and his wife then returned to Florence. During this period he visited Pisa and then travelled to Venice, where he attended the inauguration of the then-restored St Mark's Campanile (tower), and wrote about it in his sketch Feest van San Marco ("The party of San Marco").[3]: p.416 Meanwhile, publisher L.J. Veen gave a positive answer to Couperus' question if he would be willing to publish the bundled sketches.[3]: p.420 As a result, in 1912 and 1913 Uit blanke steden onder blauwe lucht ("From white cities under blue sky") appeared in two parts. Couperus travelled from Venice to Igis and to Munich, where he visited a performance of Calderóns El mayor encanto, amor in the Künstler-Theater and a performance of Mozart's Don Giovanni at the Residenz-Theater. When Couperus celebrated his 50th birthday, Het Vaderland paid tribute to him by letting his friends and admirers publish praising words. Those friends and admirers included but were not limited to Frans Bastiaanse, Emmanuel de Bom, Henri van Booven, Ina Boudier-Bakker, Marie Joseph Brusse (the father of Kees Brusse), Herman Heijermans and Willem Kloos.[3]: p.442 A committee was formed to collect the funds required for Couperus to make a journey to Egypt. Members of that committee were for example Pieter Cornelis Boutens, Alexander Teixeira de Mattos and K.J.L. Alberdingk Thijm.[3]: p.444 Couperus however could not make this journey to Egypt because of World War I.

On 29 September 1913, Johan Hendrik Ram killed himself, shooting a bullet into his head. Couperus returned to Florence later that year and attended the futuristic meeting of 12 December, which was also attended by Giovanni Papini and Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, at whom potatoes were thrown. Couperus admired them for their courage to speak despite the fact the public made so much noise they could hardly be heard.[3]: p.457 He also went to see the Mona Lisa, which had been found after it was stolen, at the Uffizi. Couperus said about new things such as futurism: The only thing that always will triumph in the end, above everything, is beauty.[3]: p.458 In these years he started reading Giovanni Papini's Un uomo finito; he compared the new literary movement to which Papini belonged, with those of the Tachtigers in the Netherlands. He wrote an article about Papini's book, which he called magnificent, an almost perfect book, and he compared Papini with Lodewijk van Deyssel. Papini and Couperus met in Florence and Couperus found Papini rather shy.[3]: p.460 Meanwhile, Elisabeth Couperus-Baud translated Pío Baroja's La ciudad de la niebla. During this time Couperus' Wreede portretten (Cruel portraits) were published in Het Vaderland. De Wrede portretten were a series of profiles of pension guests whom Couperus had met during his travels in Rome and elsewhere. He also had a meeting with Dutch actress Theo Mann-Bouwmeester, who suggested to change Langs lijnen van geleidelijkheid into a play; although this plan did not come into reality for Couperus it opened possibilities for his books in future.[3]: p.467

Public performances[edit]

When World War I began, Couperus was in Munich. On 27 August 1914 the son of Rupprecht, Crown Prince of Bavaria, Luitpold, died of polio and Couperus went to see his body in the Theatrine Church. During this time he admired the German: I admire them because they are tragic and fight a tragic struggle, like a tragic hero fights.[3]: p.471 In September he returned to Florence and in February 1915 to the Netherlands, where he visited the premiere of Frederik van Eeden's De heks van Haarlem (The witch of Haarlem) and met Van Eeden. He made a translation of Edmond Rostands Cantecler, although the play was never performed on stage. During this time Couperus started making performances as an elocutionist. His first performance at the art room Kleykamp for an audience of students from Delft was a huge success. The decor consisted of a Buddha and a painting made by Antonio da Correggio that Abraham Bredius had lent for this occasion. Couperus read De zonen der zon (Sons of the sun) aloud.[3]: p.482 While Couperus made his performances, L.J. Veen published the first parts of Van en over alles en iedereen (By and about everything and everyone) and publisher Holkema & Warendorf De ongelukkige (The unfortunate) (1915). Couperus himself wrote that year De dood van den Dappere (The death of the brave one), which dealt with the end of El Zagal and started to write De Comedianten (The comedians), inspired by the Menaechmi; this book was published with Nijgh & Van Ditmar in 1917.[3]: p.513 Couperus read Ludwig Friedländers Darstellungen aus der Sittengeschichte Roms in der Zeit von August bis zum Ausgang der Antonine to increase his knowledge of Ancient Rome which he needed for De Comedianten.

In these years Couperus met S.F. van Oss, who was the founder of De Haagsche Post, who asked if Couperus would be willing to write for his magazine. Couperus later published his travelogues (made during his travels to Africa, Dutch East Indies and Japan) as a result in De Haagsche Post, as well as many epigrams.[3]: p.523 For his friend Herman Roelvink he translated the play written by George Bernard Shaw, Caesar and Cleopatra (1916). As from December 1916 he restarted writing his weekly sketch in Het Vaderland, for example Romeinsche portretten (Roman portraits), during which he was inspired by Martial and Juvenal. He also continued giving performances for the public in the evening. In 1917 he wrote the novel Het zwevende schaakbord (The floating chessboard), about the adventures of Gawain; this novel was first published as a serial in the Haagsche Post. He read as research for this book Jacob van Maerlant's Merlijns boec and Lodewijk van Velthem's Boec van Coninc Artur ("Book of King Arthur").[3]: p.545 In July 1918 publisher L.J. Veen sent Couperus a translation of Vitruvius' De architectura and Couperus wrote about it in Het Vaderland. Meanwhile, het Hofstadtoneel (Residence Theater) was about to perform the stage version (made by Elisabeth Couperus-Baud) of Eline Vere; this play received bad product reviews. During this period of his life Couperus read the works written by Quintus Curtius Rufus, Arrian and Plutarch to find inspiration for his next work Iskander.[3]: p.568 The year 1919 was not a happy one for Couperus: his favourite nephew Frans Vlielander Hein died together with his wife when his ship was hit by a mine and L.J. Veen, his publisher and his brother-in-law Benjamin Marinus Vlielander Hein died that year as well.

Last years[edit]

In 1920 Iskander (a novel about Alexander the Great) was published in Groot Nederland; critics were not positive because of the many gay scenes. In October 1920 Couperus travelled for the Haagsche Post to Egypt; his travelogues were published weekly. In Africa he visited Algiers, travelled to Constantine, Biskra, Touggourt and Timgad and then continued his journey to Tunis and the ruins of Carthage, where he met a pupil of Marie-Louis-Antoine-Gaston Boissier. After this Couperus went back to Algiers, because he wanted to see the boxing skills of Georges Carpentier. Afterwards he wrote: I thought that in my life I have written too many books and boxed too little.[3]: p.595 On 3 May 1921 Couperus and his wife returned to Marseille and travelled to Paris, in time to be present at the festivities held for the canonization of Joan of Arc. On 1 June, Couperus and his wife left for England, where they would meet Alexander Teixeira de Mattos and during which visit Couperus wrote With Louis Couperus in London-Season; these stories were published in the Haagsche Post. In England Couperus met Stephen McKenna and Edmund Gosse. McKenna had written the forewords for Majesty and Old People and the Things that Pass. He also met Frank Arthur Swinnerton during a lunch and went to a Russian ballet in the Prince's Theater, where the orchestra was conducted by Ernest Ansermet.

He also met with his English publisher, Thornton Butterworth, visited a small concert, where Myra Hess played and also had meetings with George Moore and George Bernard Shaw.[3]: p.605 Couperus also had his photograph taken by E.O. Hoppé after which he had a meeting with the Dutch consul in London, René de Marees van Swinderen and a diner at the house of H. H. Asquith. The next day Couperus went to the Titmarsh club, where he met William Leonard Courtney, and heard Lady Astor, whom he had previously met in Constantine, speak in the House of Commons. Soon after this Couperus and his wife returned to the Netherlands.

In the Netherlands Couperus prepared himself for his journey to the Dutch East Indies, China and Japan. He and his wife left for the Dutch East Indies on 1 October 1921 aboard the mail ship Prins der Nederlanden. They left the ship at Belawan to stay with their friend Louis Constant Westenenk at Medan. In Batavia he dined with Governor-General Dirk Fock and also held public performances, where he would read out his books. After a visit to the Borobudur Couperus and his wife visited Surabaya and Bali. On 16 February they left for Hong Kong and Shanghai.[3]: p.635 In Japan they visited Kobe and Kyoto; in this last place Couperus became seriously ill, was diagnosed with Typhoid fever and was sent to the International Hospital in Kobe. After seven weeks he was fit enough to travel to Yokohama. He and his wife stayed for two weeks at the Fujiya Hotel, where Couperus read Kenjirō Tokutomi's novel Nami-Ko. He and his wife then travelled to Tokyo, where they stayed with the Dutch consul and visited Nikkō. They returned to the Netherlands on 10 October 1922.[3]: p.644

Death and tributes[edit]

Back in the Netherlands, it turned out that Couperus' kidneys and liver were affected. Despite his illness Couperus wrote a series of sketches for Het Vaderland and Groot Nederland. He also was able to visit the opera again and went to see Aida. In 1923 the couple moved to De Steeg, where Couperus received the rather prestigious Tollens prize.[10] Meanwhile, a committee was formed to celebrate Couperus' 60th birthday and gather funds as a birthday gift. Couperus' health deteriorated rapidly and apart from lung and liver problems Couperus suffered from an infection in his nose. During Couperus birthday party a sum of 12,000 guilders was handed over to him and speeches were held by Lodewijk van Deyssel and minister Johannes Theodoor de Visser; Couperus was also appointed knight in the Order of the Netherlands Lion.[11] During the following reception minister Herman Adriaan van Karnebeek and Albert Vogel, among many others, paid Couperus their respect.[12] On 11 July 1923, Couperus was brought to hospital (in Velp), because the infection in his nose had not healed, but came back home a day later. He now suffered from erysipelas as well as sepsis in the nose. He fell into a coma on 14 July, remained in that state for two days with high fever and died on 16 July 1923.[13] He was cremated at Westerveld, where Gustaaf Paul Hecking Coolenbrander (a nephew), among others, spoke to remember Couperus.

Bibliography[edit]

Books published during Couperus' life[edit]

Poetry[edit]

- Een lent van vaerzen (1884) ("A ribbon of poems")

- Orchideeën. Een bundel poëzie en proza (1886) ("Orchids, a collection of prose and poetry")

- Williswinde (1895) ("Williswinde")

Novels[edit]

Translations by Alexander Teixeira de Mattos [1865-1921] unless noted otherwise.

- Eline Vere (1889); Translated into English by J. T. Grein as Eline Vere (1892); revised translation published in 2009 by Holland Park Press and new translation published in 2010 by Archipelago Books, NY.

- Noodlot (1890); Translated into English by Clara Bell as Footsteps of Fate (1891).

- Extaze. Een boek van geluk (1892); Translated into English as Ecstasy: A Study of Happiness (1897).

- Majesteit (1893); Translated into English as Majesty: A Novel (1895)

- Wereldvrede (1895) ("World peace")

- Metamorfoze (1897) ("Metamorphosis")

- Langs lijnen der geleidelijkheid (1900); Translated into English as Inevitable, The Inevitable (1920) or The Law Inevitable (1921).

- De stille kracht (1900); Translated into English as The Hidden Force: A Story of Modern Java (1921); revised edition with an introduction and notes by E.M. Beekman (1939-2008), Amherst : University of Massachusetts Press, 1985, 1992.

- De boeken der kleine zielen. De kleine zielen (1901); Translated into English as The books of small souls. Small Souls (1914).

- De boeken der kleine zielen. Het late leven (1902); Translated into English as The books of small souls. The Later Life (1915).

- De boeken der kleine zielen. Zielenschemering (1902); Translated into English as The books of small souls. The Twilight of the Souls (1917).

- De boeken der kleine zielen. Het heilige weten (1903); Translated into English as The books of small souls. Dr. Adriaan (1918).

- Dionyzos (1904)

- De berg van licht (1905/6) ("The mountain of light")

- Van oude menschen, de dingen, die voorbij gaan... (1906); Translated into English as Old People and the Things that Pass (1918)

- Antiek toerisme. Roman uit Oud-Egypte (1911); Translated into English as The Tour: A Story of Ancient Egypt (1920)

- Herakles (1913)

- De ongelukkige (1915) ("The unhappy one")

- De komedianten (1917); Translated into English by Jacobine Menzies-Wilson as The Comedians: A Story of Ancient Rome (1926).

- De verliefde ezel (1918) ("The donkey in love")

- Xerxes of de hoogmoed (1919); Translated into English by Frederick H. Martens as Arrogance: The Conquests of Xerxes (1930).

- Iskander. De roman van Alexander den Groote (1920)

Novellas, fairy tales, and short stories[edit]

- Eene illuzie (1892) ("An illusion")

- Hooge troeven (1896) ("High trumps")

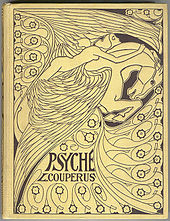

- Psyche (1898); Translated into English by B. S. Berrington as Psyche (1908).

- Fidessa (1899)

- Babel (1901)

- God en goden (1903)

- Aan den weg der vreugde (1908) ("On the road of happiness")

- De ode (1919)

- Lucrezia[nb 1] (1920)

- Het zwevende schaakbord (1922) ("The floating chessboard")

Short stories and sketches[edit]

Louis Couperus wrote hundreds of short stories, sketches, travel impressions, and letters, which were first published as feuilletons. Those feuilletons were later bundled and published as books.

- Reis-impressies (1894) ("Travel impressions")

- Over lichtende drempels (1902) ("Over Shining Doorsteps")

- Van en over mijzelf en anderen. Eerste bundel (1910) ("About me and others. Volume I")

- Antieke verhalen van goden en keizers, van dichters en hetaeren (1911) ("Antique Stories, about gods and emperors, of poets and hetaeras")

- Korte arabesken (1911) ("Short Arabesques")

- De zwaluwen neêr gestreken... (1911) ("The Swallows Landed")

- Schimmen van schoonheid (1912) ("Shadows of beauty")

- Uit blanke steden onder blauwe lucht. Eerste bundel (1912) ("From white cities under a blue sky. Volume I")

- Uit blanke steden onder blauwe lucht. Tweede bundel (1913) ("From white cities under a blue sky. Volume II")

- Van en over mijzelf en anderen. Tweede bundel (1914) ("About me and others. Volume II")

- Van en over alles en iedereen (1915) ("About everything and everyone"):[nb 2]

- Rome ("Rome")

- Genève, Florence ("Geneva, Florence")

- Sicilië, Venetië, München ("Sicily, Venice, Munich")

- Van en over mijzelf en anderen ("About me and others")[nb 3]

- Spaansch toerisme ("Spanish tourism")

- Van en over mijzelf en anderen. Derde bundel (1916) ("About me and others. Volume III")

- Van en over mijzelf en anderen. Vierde bundel (1917) ("About me and others. Volume IV")

- Jan en Florence (1917) ("Jan and Florence")[nb 4]

- Wreede portretten (1917) ("Cruel portraits")[nb 5]

- Legende, mythe en fantazie (1918) ("Legend, myth and fantasy")

- Der dingen ziel (1918) ("The Soul of Things")[nb 6]

- Brieven van den nutteloozen toeschouwer (1918) ("Letters of the useless spectator")[nb 7]

- Elyata (1919)[nb 8]

- De betoveraar (1919) ("The enchanter")[nb 9]

- Met Louis Couperus in Afrika (1921) ("With Louis Couperus in Africa")

- Oostwaarts (1923); Translated into English by Jacobine Menzies-Wilson as Eastward (1924).[nb 10]

- Proza. Eerste bundel (1923) ("Prose. Volume I")[nb 10]

- Het snoer der ontferming (1924) ("The String of Compassion")[nb 10]

- Proza. Tweede bundel (1924) ("Prose. Volume II")[nb 10]

- Nippon (1925); Translated into English by John De La Valette as Nippon (1926).[nb 10]

- Proza. Derde bundel (1925) ("Prose. Volume III")[nb 10]

Miscellaneous[edit]

- De verzoeking van den H. Antonius[nb 11] (1896)

Verzamelde werken (Collected Works)[edit]

- Jeugdwerk; Eline Vere; Novellen (1953)

- Noodlot; Extase; Majesteit; Wereldvrede; Hoge troeven (1953)

- Metamorfose; Psyche; Fidessa; Langs lijnen van geleidelijkheid (1953)

- De stille kracht; Babel; Novellen; De zonen der zon; Jahve; Dionysos (1953)

- De boeken der kleine zielen (1952)

- Van oude mensen de dingen die voorbijgaan; De berg van licht (1952)

- Aan de weg der vreugde; Antiek toerisme; Verhalen en arabesken (1954)

- Herakles; Verhalen en dagboekbladen; Uit blanke steden onder blauwe lucht (1956)

- Lucrezia; De ongelukkige; Legenden en portretten (1956)

- De komedianten; De verliefde ezel; Het zwevende schaakbord (1955)

- Xerxes; Iskander (1954)

- Verhalen (1957)

Volledige werken Louis Couperus (Complete Works)[edit]

- Een lent van vaerzen (1988)

- Orchideeën. Een bundel poëzie en proza (1989)

- Eline Vere. Een Haagsche roman (1987)

- Noodlot (1990)

- Extaze. Een boek van geluk (1990)

- Eene illuzie (1988)

- Majesteit (1991)

- Reis-impressies (1988)

- Wereldvrede (1991)

- Williswinde (1990)

- Hooge troeven (1991)

- De verzoeking van den H. Antonius (1992)

- Metamorfoze (1988)

- Psyche (1992)

- Fidessa (1992)

- Langs lijnen van geleidelijkheid (1989)

- De stille kracht (1989)

- Babel (1993)

- De boeken der kleine zielen. I en II (1991)

- De boeken der kleine zielen. III en IV (1991)

- Over lichtende drempels (1993)

- God en goden (1989)

- Dionyzos (1988)

- De berg van licht (1993)

- Van oude menschen, de dingen, die voorbij gaan... (1988)

- Aan den weg der vreugde (1989)

- Van en over mijzelf en anderen (1989)

- Antieke verhalen. Van goden en keizers, van dichters en hetaeren (1993)

- Korte arabesken (1990)

- Antiek toerisme. Roman uit Oud-Egypte (1987)

- De zwaluwen neêr gestreken... (1993)

- Schimmen van schoonheid (1991)

- Uit blanke steden onder blauwe lucht (1994)

- Herakles (1994)

- Van en over alles en iedereen (1990)

- De ongelukkige (1994)

- De komedianten (1992)

- Legende, mythe en fantazie (1994)

- De verliefde ezel (1994)

- De ode (1990)

- Xerxes, of De hoogmoed (1993)

- Iskander. De roman van Alexander den Groote (1995)

- Met Louis Couperus in Afrika (1995)

- Het zwevende schaakbord (1994)

- Oostwaarts (1992)

- Proza. Eerste bundel (1995)

- Het snoer der ontferming. Japansche legenden (1995)

- Nippon (1992)

- Ongebundeld werk (1996)

- Ongepubliceerd werk (1996)

Published letters[edit]

- Couperus, Louis; Bastet, Frédéric (1977). Brieven van Louis Couperus aan zijn uitgever (in Dutch). 's-Gravenhage.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) In two volumes: 1. Waarde heer Veen : (1890–1902) and 2. Amice : (1902–1919) - Couperus, Louis; Veen, L. J.; Vliet, H. T. M. van (1987). Louis Couperus en L. J. Veen : bloemlezing uit hun correspondentie (in Dutch). Utrecht: Veen. ISBN 9020426869.

- Couperus, Louis; Baud, Elisabeth Wilhelmina Johanna; Wintermans, Casper (2003). Dear sir : brieven van het echtpaar Couperus aan Oscar Wilde (in Dutch and English). Woubrugge: Avalon Pers. ISBN 9080731420.

Notes and references[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Published earlier as part of Schimmen van schoonheid (1912)

- ^ A series of five books, all published simultaneously in June 1915

- ^ Reprint of Van en over mijzelf en anderen II.

- ^ Reprint of Van en over mijzelf en anderen III, first half.

- ^ Reprint of Van en over mijzelf en anderen III, second half.

- ^ Reprint of Van en over mijzelf en anderen IV, first half.

- ^ Reprint of Van en over mijzelf en anderen IV, second half.

- ^ Reprint of Legende, mythe en fantazie, first half.

- ^ Reprint of Legende, mythe en fantazie, second half.

- ^ a b c d e f Published posthumously.

- ^ A translations of fragments of Flaubert's La Tentation de Saint Antoine.

References[edit]

- ^ a b Bosma, Ulbe; Raben, Remco (2008). Being "Dutch" in the Indies: A History of Creolisation and Empire, 1500-1920. NUS Press. ISBN 978-9971-69-373-2. Retrieved 18 November 2020.

- ^ Faes, J. (1902). Over de erfpachtsrechten uitgeoefend door Chineezen en de occupatie-rechten der inlandsche bevolking, op de gronden der particuliere landerijen, ten westen der Tjimanoek (in Dutch). Buitenzorgsche drukkerij. Retrieved 19 November 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba bb bc bd be bf bg bh bi bj bk bl bm bn bo bp bq br bs bt bu bv bw bx by bz ca cb cc cd ce cf cg ch ci (in Dutch)Bastet, Frédéric (1987). Louis Couperus : Een biografie (in Dutch). Amsterdam: Querido. ISBN 9021451360. Retrieved 24 April 2013.

- ^ (in Dutch) J.A. Dautzenberg, Nederlandse Literatuur, 1989.

- ^ (in Dutch) 'Een vreemde ervaring die Couperus verwerkte in de Stille Kracht', in De Telegraaf, 22 August 1987 – Retrieved on 24 March 2013

- ^ (in Dutch) 'Kunst en letteren', in Algemeen Handelsblad, 14 March 1889. Retrieved on 24 March 2013.

- ^ (in Dutch) 'Stadsnieuws', De Tijd, 15 August 1890. Retrieved on 24 March 2013.

- ^ (in Dutch) Couperusweg in Hilversum – Retrieved on 24 March 2013

- ^ Which received a bad review, as the paper wrote: A more morbid, an uglier, or a sillier story we have not read for a long time. 'Kunst en Letteren', in Algemeen Handelsblad. 30 June 1891. Retrieved 8 February 2013.

- ^ (in Dutch) 'De Tollensprijs voor Couperus', in Het Vaderland. 18 April 1923. Retrieved 24 March 2013.

- ^ (in Dutch) 'Couperus gedecoreerd', in Bataviasch Nieuwsblad. 11 June 1923. Retrieved 24 March 2013.

- ^ Lodewijk van Deyssel was one, but according to the thesis of Karel Reijders he did not speak to but about Couperus. (in Dutch) 'Couperus bij Van Deyssel een gigantische confrontatie', in Limburgs Dagblad. 6 July 1968. Retrieved 24 March 2013.

- ^ (in Dutch) 'Louis Couperus', in Limburgsch Dagblad. 17 July 1923. Retrieved 24 March 2013.

External links[edit]

- Works by Louis Couperus at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Louis Couperus at Internet Archive

- Works by Louis Couperus at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Works by Louis Couperus at Open Library

- Works by Louis Couperus (in Dutch) at the Digital Library for Dutch Literature

- Louis Couperus Society (in Dutch)